ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

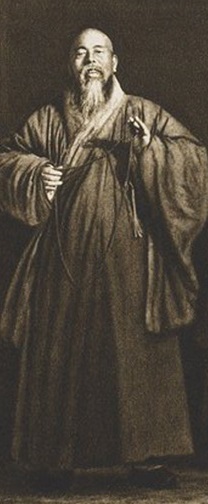

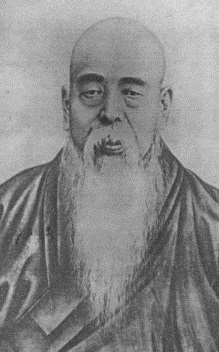

敬安 Jingan (1852-1912), aka 八指頭陀 Bazhi toutuo

Jìchán 寄禪 (1852-1912)

Lay surname 姓: Huáng 黄

Name 名: Xùshān 續山

Courtesy name 字: Fúyú 福餘

Dharma name 法名: Jìng'ān 敬安

Born January 23, 1852 (Xiánfēng 咸豐 in Shítán Township 石潭鎮, Xiāngtán County 湘潭縣, Húnán 湖南

Died November 10, 1912 (Mínguó 民國 at Fǎyuán Temple 法源寺, Běijīng 北京

Common nickname: Bāzhǐ tóutuó 八指頭陀 (The Eight-fingered Ascetic)

http://buddhistinformatics.ddbc.edu.tw/dmcb/Jichan_%E5%AF%84%E7%A6%AA

Jìchán 寄禪 (1852-1912) was a famous Chán 禪 master and poet during the late Qing. He was an important person in transitional Qing-Republican Buddhism.

Jìchán's mother died when he was young. In 1868 (Tóngzhì 同治 7), he took tonsure and preliminary ordination under Dōnglín 東林 at Fǎhuá Temple 法華寺 in Xiāngyáng 湘陽. He was 16. When he was 27, he burned off the two smallest fingers on his left hand at Aśoka Temple 阿育王寺 in Níngbō 寧波 as an offering to the relics of the Buddha housed there. He practiced Chán in different places under various masters, and when he was 34 (1888), he returned to Húnán.

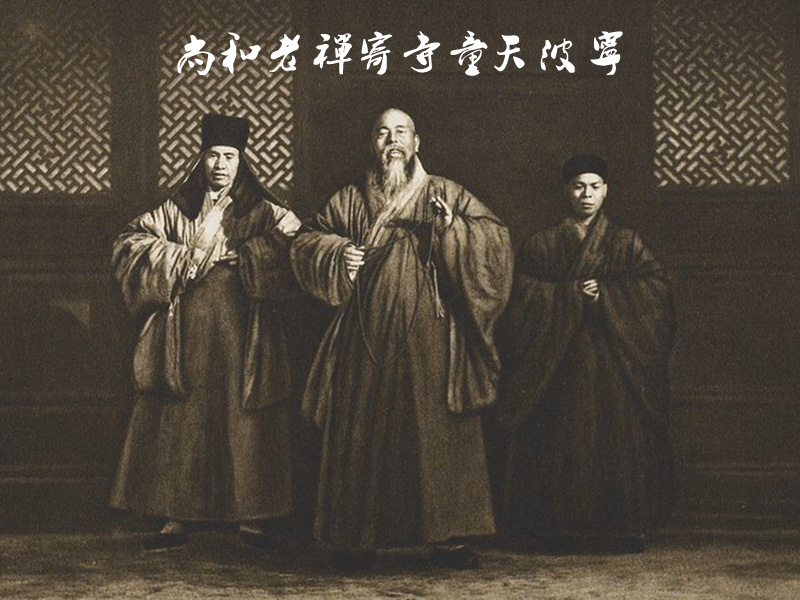

Jìchán was abbot of a number of different temples in his lifetime (see below), the last one being the famous Chán temple, Tiāntóng Temple 天童寺 in Níngbō, where he became abbot at age 52.

On April 1, 1912, Jìchán became the president of the Chinese General Buddhist Association 中華佛教總會. On November 10, Jìchán had an argument with Dù Guān 杜關 , the Minister of the Interior, over ratification of the Association's charter. This exchange upset Jìchán a great deal and he died that night.

http://ir.lib.nknu.edu.tw/handle/987654321/5388

釋敬安( 1851-1912 年),俗姓黃,名讀山。字寄禪,是山谷老人的裔孫。曾於阿育王寺佛舍利塔前燃二指供佛,於今剩下八指,故自稱八指頭陀。本論文共分七個章節,因相關資料不多,故從其詩集來探索。其詩的精神有儒釋道的思想,以及近似屈原、陶淵明、杜甫和黃山谷的思想。

敬安從見籬間桃花為暴風雨摧敗慨歎生命而出家,隔年到歧山修陀頭行;遊洞庭湖,感得「洞庭波送一僧來」而習詩。越五年東遊 吳越,二十七歲於四明玲瓏岩閉關後,四處行 腳,曾為住持。五十二歲入主天童寺,其間為「保教扶宗,興立學校」而奔走不歇。寧波僧教育會成立,推為 會長,在寧波創辦僧 ? 小學、民眾小學,為我國佛教辦學之始。 1912 年各地佛教代表集於上海留雲寺,籌組「中華佛教總會」,公推為首任會長。九月前往北京,為請求政府下令各地禁止毀廟奪寺 產,反被侮辱,憤而辭出。當晚回法源寺,胸隔作痛,示寂。得壽六十二年,僧臘四十五年 。

敬安喜好作詩,早期作品頗多禪理詩,中晚期更多關懷民瘼之詩,對清末時局倍感憂心;憂時憂民憂國憂教縈繞一生,是一位愛國的詩僧。從其喜好作詩到嗜好作詩,到戒詩;又止不住作詩,進而欲罷不能;而擺盪在詩與禪的掙扎,再到詩與禪融和,終而詩禪相映;這時敬安已五十八 歲 。其詩風格清寒,接近「郊寒島瘦」。到中晚年詩格轉趨雄渾。

敬安酷好作詩,酷詠白梅,有「白梅和尚」之稱。詩中巧用「影」字,有「三影和尚」之稱。以詩文交際,人脈豐厚,豐厚的人脈成就其對佛教的貢獻;為保護寺 產北上請命,這為其畫下美好的句點 。

Venerable Ching-An (A.D.1851-A.D.1912, whose name was Tu-Shan Huang, and was nicknamed Chü-chian, was the grandson of Old Man Shan-Ku. He burned two of his fingers while worshipping the Buddha in the front of the Tower of Buddha's Relics at the Temple of King Ar-?. As he only had eight fingers, he called himself the “Buddhist monk of eight fingers”. The research of the poetry of the Buddhist monk of PaChi includes seven chapters. As there are only a few papers about the Buddhist monk of PaChi and his poetry, I read and collected extracts from his poems. His poems describe the traditions of Ju Shi and Tao; as done so by the other Chinese poets, like Ch'ü Yüan, Tao Yüan-ming, Tu Fu and Huang Ting-chian.

While seeing the peach blossoms on the fence destroyed by the storm, Tu-Shan was dejected by unfulfilled life and decided to become a monk. The next year, he had became a monk at the temple of J?n Jui. While back home to visit his uncle, he passed the Tung Ting Lake, and while gazing into the water, he thought “Buddhist monk leading back by the wave of Tung Ting Lake”. He practiced writing poetry. Five years later Ching-An had a tour on the Wu-?eh. At 27, after a period of isolation in Lin lung, he began to wander and become a housemaster at several temples. At 52, he had been a housemaster at the Tien Tung Temple and taught Buddhism. The association of Buddhist education was established at Lin Po and Ching-An was chosen to be the leader. It was the first time a Buddhist elementary school was established for the public. In A.D.1912, Buddhist representatives gathered at the Liu- ?n temple at Shanghai to hold a meeting and form the General Association of Buddhism of China. Ching-An was chosen as the leader. Leaving for Pei-Chin to petition for the government to permit protection of the Buddhist and their temples; Ching-An was insulted by the governor. When he returned to Fa-?an temple that night, Ching-An died of a heart attack at age 62. He was a monk for 45 years of his life.

Ching-An was fond of writing poems. There are many poems of Zen in his earlier writing and more poems about concern for other people written in later years. He was concerned for his country and people; especially about the union of the Buddhist monks and as a result, he was called a patriotic poet. The process of from writing to forbid writing and then writing again crazily always confused all his life. Ching-An had a strong desire to writing poetry, but was conflicted between poetry and Zen, until he found harmony between them in his old age. Finally, there is a balance between the poetry and Zen. In his poetry, there is a cold style as with other poets like the poets, the M?ng-Chiao and the Chia-Tao. When he is middle aged, his poetic style had become full of aesthetic strength.

Ching-An was a hobby-writer of poetry and mostly love to write the poetry about white–plumed blossoms. He was called “the white-plumed monk”. In particular, His poetry frequently used the word “shadow”, so he was called the “monk three shadows”. Ching-An made a social through writing poems with his friends, which was helpful for him to work for Buddhists. When petition for the protection of the estates of the temple, he left for Pei-Chin; and this action gave his life perfect ending.

Two Poems

by Jing An (Eight Fingers)

Translated by Dongbo 東波

http://www.mountainsongs.net/poet_.php?id=125

Flowing Water

Flowing water

cannot carry off flower shadows,

Wilted flowers

by themselves fall and flow eastward.

Falling flowers, flowing waters

by their nature have no will,

Yet their passage causes men much sorrow.Late Autumn Regrets

Alone in mist, no trace of my body,

Three times south to hear frosty bell.

Glimpse of wild geese, thoughts of home,

Mountains also grieve, wrapped in gloom.

When old friends meet by chance,

Anxious Chan creates striking couplets.

But I sigh, my mendicant wish unfulfilled,

Ten thousand black mountains disappointed.

The Humanitarian Concerns and Zen Image of Poems of the Poetic Monk BaZhiTouTuo in the Late Ching Dynasty

by Huang Jing-Jia Assistant Professor, Department of Chinese Language and Literature, National Taitung University

http://bec001.web.ncku.edu.tw/ezfiles/335/1335/img/1450/2904.pdf

Abstract

The monastic title of BaZhiTouTuo (1851-1912) is Jing-an, who is also named as Ji-Chan. He once swore to devote himself fully to the Buddhism and titled himself as BaZhiTouTuo. BaZhiTouTuo had a twisted life journey, which made him a person of self-abnegation, a Buddhist leader of the late Ching Dynasty, and a magnificent poetic monk. This article centers on BaZhiTouTuo, investigates the plural meanings of his poems, and gauges the achievement of monk poets in the late Ching. On one hand, the study tackles personal friendships and Huxiang culture that shapes BaZhiTouTuo's temperament and moral practices situated in the context of political environment and Buddhism reforms in the late Ching. On the other hand, it observes BaZhiTouTuo's interaction with the poet community in the social and cultural context of the late Ching and probes into his social participation in the age of political revolt. In addition, this study looks into BaZhiTouTuo's sensibility, rationality and spirituality and discusses the embodiment of his personal emotion, care for the society and spiritual cultivation. Uncovering different dimensions and spheres of spirituality in BaZhiTouTuo's life, the study analyzes his works, including his letters, talks, autobiography and inscription, in order to understand and construct a cultural image of him, which represents his personal dedication to life and cultural subjectivity. Finally, the study evaluates the values of creation and position of BaZhiTouTuo in the circle of poetic monks and in the history of the late Ching.

八指头陀诗选集

http://ce.sysu.edu.cn/hope2008/Environment/ShowArticle.asp?ArticleID=10919

Ching An (1851–1912)

Translations by J.P. Seaton

In: The Clouds Should Know Me By Now: Buddhist Poet Monks of China

Wisdom Publications, 1998, pp. 173-198.

INTRODUCTION

CHING AN, A NATIVE of Hsing-t’an, in Hunan Province, entered the Fa-hua Monastery there at the age of seventeen. Orphaned early in life, he probably received most of his considerable secular education in the monastery, along with his religious training. Ching An was purportedly a gifted poet even as a child: it is said he was able to make poems even before he learned to write, chanting them to be transcribed. Although precocious literary ability is a common part of traditional literary hagiography, the extraordinary quality of his mature works makes this particular anecdote easy to believe.

Early in his career, he burned off two fingers as a votive offering to the Buddha, a spectacular gesture even within the tradition of self-mortification that accompanied much Buddhist practice in China. It earned him the by-name Pa-ch’ih T’ou-t’uo,The Eight-Fingered Monk.The episode also produced, much later in his life, one of the poems included in this selection, a disarmingly rueful look at youthful enthusiasm in which the mature poet asks, “Did I really think I could become a Buddha / one slice at a time?”

Ching An was the abbot of several famous monasteries, and his poetic reputation spread widely throughout both Ch’an and lay literary circles. His poetry certainly demonstrates the longevity of the Ch’an poetic tradition and its vitality during the difficult social and political climate of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when the Ch’ing dynasty was collapsing under the weight of its own corrupt senescence and the onslaught of Western colonialism. In the poems of this selection, the poet avoids both the Buddhist technical vocabulary and overt moralizing that is a feature of Buddhist poetry by lesser poets of the tradition. He shows a deep familiarity with the lay poetic tradition; but, while allusions to the works of poets like the Ch’an layman Wang Wei of the T’ang are evident in many poems, his poems are always fresh, vivid, and original.

Wang K’ai-yun (1833–1916), a lay friend who was arguably the finest classical poet of the late Ch’ing, favorably compared Ching An’s work to that of the legendary wild-man monk Han-shan. It is a surprising comparison, considering the fact that Ching An was a successful abbot and a recognized leader in the relations between the monastic community and the central government, but it is a particularly apt one. Like Han-shan’s poems, Ching An’s are sharply personal and even apparently iconoclastic. I have commented, at some length, on his poetic technique in a note to one of the poems in this selection.

Ching An was also compared by contemporaries to the famous late T’ang Buddhist poet Chia Tao (779–843), a selection of whose poems are translated in this book. One reason for the association of Ching An with Chia Tao may very well have been the practical role that he attempted to play in the world of politics. Unlike Chia Tao, Ching An didn’t embrace Confucian orthodoxy and serve in the Imperial government. After the fall of the Ch’ing dynasty he did, however, go to Beijing to represent the many monks and great monasteries of Chekiang and Jiangsu Provinces. His attempt to help in the founding of a national Buddhist organization to protect the Buddhist cultural heritage and to promote a role for the sangha in the new Republic was unsuccessful. He died there, in residence at the ancient Fa-yuan Monastery, in 1912. Ching An was an extraordinary poet and a brilliant emblem of the vitality of the Ch’an tradition at the beginning of this century.

Note on Personal and Geographical Names

Though I have no doubt they were real people, I’ve been unable to locate either Shih-chia Tzu or the drunken calligrapher Hsu in either standard or specialized Buddhist biographical dictionaries. Neither have I been able to locate Lushan Temple in the standard geographical dictionary. The rest of the geographical names refer to places in the area in which Ching An lived most of his adult life—the scenic area in east-central China from Hangchou northward through Chekiang and Jiangsu—that was also the cultural center of China in the later dynasties. I hope that further research on the poetry and life of Ching An reveals him and his milieu in a clearer light, but, certainly, the poems reveal his art and his spirit in the clearest light possible.

ON THE ROAD: A SPRING DAY AT LING-FENG

Spring comes, together with a rush of feelings.

I go, alone, to knock at a grotto's gateway.The grass by the stream rides green on my clogs:

The canyon clouds climb white on my robe.Fallen flowers? With the stream's flow,

they'll get where they're going.

Wild birds? They'll fly along with me.When I was near the end of the woodcutter's way

it was only the bell song led me out

from among the hillside's subtle iridescent blues and greens.

AT LUSHAN TEMPLEIn the shimmer of distance

the bell speaks pure Sanskrit

seeing off the slanting sun.Secret, silent

blossoms beneath

the overhanging cliffs

send their fragrance on the stream.In the single wind chime at the temple's eaves

the wind speaks for itself.Before my window, ten thousand trees,

the rain's the first Fall chill.The hills, locked in cloud essence,

pry into my purity.The river carries the ancient sound of the billows

all the way to the sea.I won't admire the thousand-year crane

that nests the ageless pine.He doesn't know that in the human world

groves turn to seas.

ON THE SPOT WHERE SHIH-CHIA TZU

SITS IN MEDITATIONTen thousand trees

cold forest

as I came up through the blue greens of the hillside.Wafting in the wind

white crane, my feathery head

a long time beyond scheming.The sound of the stream

is, after all,

without a present, or a past.The beauty of the mountain colors:

what could it have to do

with “right” or “wrong”?The lush grass of the high pass

may certainly mislead

the wanderer's clogs.Cliffside flowers

sometimes fall

on a robe that's sitting zazen.If you ask the teacher

when

he came to sit on T'ien-t'ai Mountain:“Green pines I planted

with my own hands:

ten hands' span, now.”

PASSING BY WHERE HSU, “THE WINE-FLUSHED

IMMORTAL,” USED TO LIVE

(“The Wine-flushed Immortal” was good at drinking and good at

doing calligraphy drunk. He called himself “the drunken wanderer

of Ssu-ming Mountain.” For a longer discussion of this poem, see

the note at the end of this section.)Gate in a lane

chill, bleak, artemisia grows

and tall green weeds.Mango birds, pretty girls

still come as if to urge you:

Drain the bowl!Wild crab apple blossoms

mouth the rain.

Pear blossoms, white.But no longer to be seen

high on the essence of the creative

that old wine bibber of Kao Yang.

DUSK OF AUTUMN:

WRITING WHAT MY HEART EMBRACESI am the orphan cloud:

no trace left behind.Come South three times now

to listen to the frosty bell.When men see geese flying

they think of letters home.Even the mountains grieve at the Fall:

they're wearing a sickly face.But fine phrases are there too

to be plucked from the sad heart of Autumn,

and many an ancient poet ran into one on the road.I'm ashamed I've yet to realize

my monk's oath:

the fault's in this load of blue green hills I carry

many tens of thousands strong.

FACING SNOW AND WRITING

WHAT MY HEART EMBRACESAt Mount Ssu-ming

in the cold in the snow

half a lifetime's bitter chanting.

Beard hairs are easy to pluck out

one by one:

a poem's words are hard

to put together.

Pure

vanity

to vent the heart and spleen;

words and theories, sometimes, aren't enough.

Loneliness, loneliness

my everyday affair.

The soughing winds

pass on the night bell sound.

TO SHOW YOU ALL,

ON THE FIRST MORNING OF THE YEARA thousand thousand worlds,

a single breath,

one turn of the Great Potter's Wheel.

The withered tree blossomsin a Spring beyond illusion.

Pop!

The firecrackers bring me back:the laugh's on me.

This year's man

is last year's man.

THIRD TIME WANDERING

TO CLOUD SLUICE PEAKPropped on tough bamboo

three times now I've climbed

this tower of mysteries.So I can write another poem

I brush the moss from stone.The cranes in the clouds

must know me by now:every year we both come here for the Autumn.

BEATING THE HEAT AT JADE LAKEWest of the painted bridge

east of the willow's shade:

ten li of flat lake:

water touching, holding, sky.

Not like it is among men,

bitter at the burning heat.

Monk's robe sits idle:

lotus blossoms: breeze.

NIGHT SITTINGThe hermit doesn't sleep at night:

in love with the blue of the vacant moon.

The cool of the breeze

that rustles the trees

rustles him too.

WRITTEN ON THE PAINTING “COLD RIVER SNOW”Dropped a hook, east of Plankbridge.

Now snow weighs down his straw rain gear

it's freezing.

The River's so cold the water's stopped running:

fish nibble the shadows of plum blossoms.

RETURNING CLOUDSMisty trees hide in crinkled hills' blue green.

The man of the Way's stayed long

at this cottage in the bamboo grove.

White clouds too know the flavor

of this mountain life;

they haven't waited for the Vesper Bell

to come on home again.

OVER KING YU MOUNTAIN WITH A FRIENDSun sets, bell sounds, the mist.

Headwind on the road, the going hard.

Evening sun at Cold Mountain.

Horses tread men's shadows.

ON A PAINTINGA pine or two,

three or four bamboo,

cliffside cottage, long, solitary, silence.

Only floating clouds come to visit.

MOORED AT MAPLE BRIDGEFrost white across the river

waters reaching toward the sky.

All I'd hoped for's lost

in Autumn's darkening.

I cannot sleep, a man

adrift, a thousand miles

alone, among the reed flowers:

but the moonlight fills the boat.

CROSSING THE YANG-CHIA

BRIDGE ONCE MOREThe face reflected in the stream's

lost half its youthful color.

Spring wind

is as it was before,

so too, the thousand willow boughs.

Crows perch to punctuate

the lines of slanting sunset.

It's hard to write

as I pass this place once more.

AT HU-K'OU, MOURNING

FOR KAO PO-TSUThough he was young, Kao

was the crown of Su-chou and Hu-k'ou.

It was only to see if he was still here

that I came today to this place…

found a chaos of mountains

no word

this evening sun

this loneliness.

LAUGHING AT MYSELF ICold cliff

dead tree

this knobby pated me…

thinks there's nothing better than a poem.

I mock myself, writing

in the dust, and

damn the man who penned the first word

and steered so many astray.

LAUGHING AT MYSELF IISlices of flesh made burnt offering

to the Buddha.

Just so, I came to know myself

a ball of mud dissolving in the water.

I had ten fingers. Now, just eight remain.

Did I really think I could become a Buddha

one slice at a time?Note to “Passing by Where Hsu, ‘The Wine-flushed Immortal,' Used to Live”

I often set aside the draft of a poem I love in the original when it becomes apparent that it will require a footnote in English. This poem is so nice and so representative of a number of features of Ching An's style that I have paraphrased in the translation in an attempt to maintain the poem's integrity in American English. I am providing this note to help the reader understand the techniques that the paraphrase tries to capture. The first paraphrase is in line two, where the mango birds (or orioles, if you prefer) are a conventional metaphor for fashionable prostitutes, or professional “entertainers.”The play of sensuality in Ching An's work is intentional and appropriate to a worldly Zen that acknowledges that while phenomena are empty they are nonetheless attractive. The drunken calligrapher was certainly visited by fashionable ladies of the entertainment quarter, and what he did with them was their business. So, for the reader who needs to be reminded to look at birds and flowers in a Chinese poem as “the birds and the bees,” I have added “pretty girls” at the denotational level, even though they are only there as an allusion, or at the connotational level, in the original.

The second paraphrase comes in the last line.There I have trampled on my own rules for translation by inserting an interpretive line before the literal rendering.The verbatim translation of this line is “Not / See / High /Yang / Old / Wine / Disciple.” In this “literal” rendering of the line I have read High Yang as a geographical name, something perfectly justifiable, and certainly what Ching An intended us to do at the first level of interpretation. Following Western convention, I have thus rendered it as “Kao Yang,” giving only the transliteration of the character for high or tall (Kao) and for Yang (the Yang of Yin andYang).This is typical of the way translators render Chinese geographical names into English: for example, the name of the T'ang dynasty's imperial capital, Ch'ang-an, is usually transliterated rather than translated as Long (or Eternal) Peace. There are places in T'ang poetry, particularly after the An Lushan rebellion turned the capital into a perpetual center of armed struggle, where poets like Tu Fu clearly used its names with a certain ironic relish, but it is generally acceptable to simply transliterate its name. Here, though, a look at the meaning of the two characters involved may make it clear why I've been tempted to break my own rules of translation and even to write a footnote. Kao means “high,”“tall,” or, in more formal discourse,“eminent.” Yang means “Yang,” as inYin andYang; it is the active principle, the essence, the virtue of creativity. Old Mr. Hsu, drunk as a High Lord and full of Yang, attracts pretty entertainers, and creates characters in wild grass writing. He's the image, or perhaps the envy, of the spirits.And, lest all this wildYang threaten the puritanical, let it be noted that Ching An clearly points out that the old drunk is gone, dead. However, I doubt Ching An's point was intended to be puritanical: some Ming and Ch'ing Zen men were often as wild as some modern Tibetan Buddhists.

To take it even a step further, I'll point out that the wine bibber in the last line is derived from the Shih Chi (Records of the Grand Historian) of Ssu-ma Ch'ien, the first great historian of China. It is quite possible that Ching An derived this allusion indirectly from a quotation of the Shih Chi in a poem by Kao Shih, the seventh-century scholar-official-poet and friend of Tu Fu. Ching An, despite his humble social origins, was a truly erudite man.Though he may very well have grabbed the allusion from the enormous poet's phrase book, P'ei-wen Yun-fu, as was the common practice of Ch'ing and even Ch'ing Zen poets, it is a good grab.The presence in this poem of other vocabulary from the Kao Shih poem suggests that Ching An wanted his readers to know that source and probably to read it.

The allusion suggests another layer of meaning in the poem too (the only good reason for an allusion). Li I-chi, the historical man behind the allusion, is presented in the original source ( Shih Chi , 97) as a man who lived a life of reclusion during the last chaotic years of the Ch'in dynasty, becoming known in his own neighborhood as a “madman.” When Li I-chi was later identified as a Confucian scholar in hiding by the first Emperor of the Han (ca. 200 B.C.E.), he had to claim he was merely a “drunk” so that the emperor would grant him an audience, at which he offered his services to him. Before he was tutored by the likes of Li I-chi, the self-proclaimed “wine bibber of Kao Yang,” the first Emperor of the Han used to express his opinion of Confucianism by urinating in the ceremonial hats of “Confucians” when they came for an audience.

As the Ch'ing dynasty began to collapse under the domination of the alien Manchus, many of the Chinese literati excused themselves from service to its emperors on any grounds conceivable. Many became recluses, feigning exotic personalities, simply to avoid being called to service.The allusion may thus be an attempt to provide an explanation, or an excuse, for the calligrapher's drinking habits that is simultaneously a restatement of Ching An's well-known anti-Manchu political stance. Or it may simply be Ching An's way of investing the late Mr. Hsu with an aura of respectability by suggesting that he's not just a drunk. The one might be an example of what I've heard called politically engaged Buddhism. The other might represent compassion for the old calligrapher's survivors.

This poem is real live Zen, it seems to me. The sound of one damned good poet getting really deep into the complexities of the simple life.

波天童寺八指头陀寄禅老和尚德像——摄于1906-1909年间

http://zenmonk.cn/cxjw.htm