ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

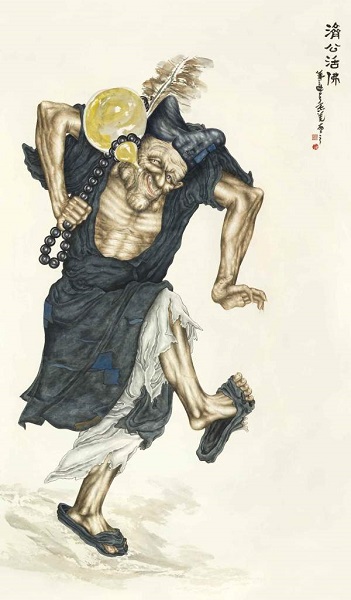

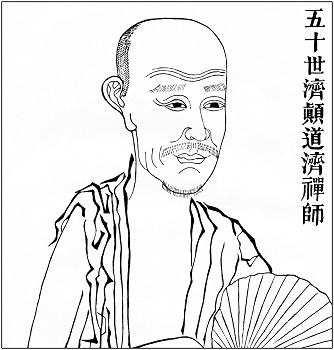

濟公活佛 Jigong huofo (1133-1209), aka 道濟 Daoji

济公 Ji Gong, 李修元 / 李修緣 Li Xiuyuan, 濟顛道濟 Jidian Daoji

濟顛道濟 Jidian Daoji

Daoji (2 February 1130–16 May 1207), commonly known as Ji Gong, was a Chán Buddhist monk of the Southern Song Dynasty in China. He was born with the name of Li Xiuyuan. (李修元). Some sources have cited his name as Lǐ Xiūyuán (李修 缘, the only difference being the third character of his name). Dao Ji was also called Hu Yin (Recluse from the Lake) and Elder Fang Yuan (Square Circle). Ji Gong was a buddhist monk but drank alcohol and ate meat. His image usually wears a monk hat (called Ji Gong Mao), carrying a reed fan and a gourd.

Jigong huofo painted by contemporary Chinese artists (DOC)

马哲 Ma Zhe (1952-): 济公活佛百态图《缘起赞禅意卷》

http://www.360doc.com/content/12/0315/13/5975523_194525675.shtml

http://kadxlt.blog.163.com/blog/static/204561151201262142716627/ (1)

http://kadxlt.blog.163.com/blog/static/20456115120126214222820/ (2)

Ji Gong (濟公), The Drunk Monk - bamboo root carving

http://thetaiwanphotographer.com/taiwan-god-ji-gong-%E6%BF%9F%E5%85%AC-the-drunk-monk/

Crazy Ji: Chinese Religion and Popular Literature

by Meir Shahar

Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series, 48 . Cambridge (MA) and London: Harvard University Press, 1998. xviii, 330 p.

http://ccs.ncl.edu.tw/Chinese_studies_18_2/18_2_18.pdf

PDF: Adventures of the Mad Monk Ji Gong

The Drunken Wisdom of China's Famous Chan Buddhist Monk

by Guo Xiaoting

translated by John Robert Shaw

Introduction by Victoria Cass (PDF)

Tuttle, 2014, 544 p.

reviewed by Vladimir K

This is the first complete English translation of a Chinese classic work that is sure to amuse and enlighten modern readers. It tells the story of the mad old Zen Buddhist monk Ji Gong, who rose from humble beginnings to become one of China's greatest folk heroes.

Follow the brilliant and hilarious adventures of a mad Zen Buddhist monk who rose from humble beginnings to become one of China's greatest folk heroes!

Ji Gong studied at the great Ling Yin monastery, an immense temple that still ranges up the steep hills above Hangzhou, near Shanghai. The Chan (Zen) Buddhist masters of the temple tried to instruct Ji Gong in the spartan practices of their sect, but the young monk, following in the footsteps of other great ne'er-do-wells, distinguished himself mainly by getting expelled. He left the monastery, became a wanderer with hardly a proper piece of clothing to wear, and achieved great renown - in seedy wine shops and drinking establishments!

This could have been where Ji Gong's story ended. But his unorthodox style of Buddhism soon made him a hero for popular storytellers of the Song dynasty era. Audiences delighted in tales where the mad old monk ignored - or even mocked - authority, defied common sense, never neglected the wine, yet still managed to save the day. Ji Gong remains popular in China even today, where he regularly appears as the wise old drunken fool in movies and TV shows. In Adventures of the Mad Monk Ji Gong, you'll read how he has a rogue's knack for exposing the corrupt and criminal while still pursuing the twin delights of enlightenment and intoxication. This literary classic of a traveling martial arts master, fighting evil and righting wrongs, will entertain Western readers of all ages!

Biography & Story of Ji Gong

http://www.mildchina.com/history-culture/monk-jigong.html

Mentioning the story of Ji Gong, in China, the first impression of people is a TV series playing the magic experiences and legend of Ji Gong, who was widely and highly respected as the Master of Zen Buddhism and the incarnation of Taming Dragon Arhat (Xiang Long Luo Han, 降龙罗汉, one of 500 Arhats in Buddhism culture). Historically speaking, Ji Gong was a true monk with a high cultivation and reputation in China. We share what we know about this figure in history and story.

Ji Gong in History

Ji Gong(济公, 1133-1209) whose earthly name was Li Xiuyuan, was born in Yongning Village, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang Province. His father was Li Chunmao and mother had a surname Wang. At the age of 18, his parents passed away. And he went to Lingyin Temple of Hangzhou and became a monk. Since then he used the Buddhist name Daoji (道济), and his teacher was Hui Yuan, an old and blind abbot and said to know the real identity of Ji Gong. Ji Gong disliked sutra chanting and meditation sitting, and he like eating meat and drinking alcohol, and even preferred garlic dog meat. All of these foods were absolutely prohibited in Buddhism. He always wore the worn-out clothes and hats and kept a broken hand fan. Due to his unrestraint, he was accused by other monks. His teacher just said a word – “the Gate of Buddhism is so vast! Why is this crazy monk not forgiven? ”. Therefore, he had a nickname Crazy Monk(济颠). After his teacher passed away, he was forced to move to Jingci Temple. He was quite proficient in the medicine and saved many people from death, and then he was respected as Living Buddha Ji Gong. Legendarily speaking, he was the earthly Arhat of Taming Dragon. On May 16, 1209, he passed away, and before going, he left a Buddhist verse.

六十年来狼藉,- Sixty years’ life in disorder

东壁打到西壁。- From east to west, I fight always

如今收拾归来,- Today, I review and return

依旧水连天碧。- All is same as those beforeHe was buried in Running Tiger Spring Area, and a special monastery named Jigong Tayuan was built in memory of him. Many historical words are written in the Records of Jingci Temple.

Ji Gong in Story

The legends of Ji Gong were sourced from the late period of Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279), and the folk storytellers begun taking his life experience as the theme, and up to Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), a storybook named Complete Stories of Ji Gong(济公全传) was published. His stories actually were sourced the story of Master Bao Zhi who living in the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420-589). Later, some folk stories and believes were blended, and Ji Gong became a featured immortal of Buddhism and Taoism. I-Kuan Tao worships Ji Gong and lists him as one of the Gods, and considers their founding master, Zhang Tianran, to be the incarnation of Ji Gong. There are lots of stories about Ji Gong. Hereinafter are the selected:

After living in Jingci Temple, Ji Gong acted as an amanuensis monk. On one occasion, the fire destroyed the main hall of Jingci Temple, the abbot turned to him for the big wood for restoring that hall, after he slept for three days because of overdrinking, he shouted at:"the wood is here, take it from well, the wood really effused from the well of temple continually until the woods were enough for rebuilding the hall. Nowadays, there is a Shenmu Well in Jingci Temple.

One day, Ji Gong fore-felt there would be a hill flying to the front of Lingyin Temple, for the sake of saving the villagers, he took the measure of looting bride to take the villages away from their houses and eventually avoided happening of disaster. This is the story illustrating the origin of Peak Flying-From-Afar (飞来峰).

If you are interested in the stories of Ji Gong, and understand Chinese, we recommend you to enjoy the solo story-telling of Guo Degang in Beijing, and his most famous story telling is the Legend of Ji Gong, in which nearly all the stories of Ji Gong are available such as Eight Devils Temper Ji Gong with Fire, Ji Gong Fighting Against Da Peng, said to be the uncle of Sakyamuni, Ji Gong Edified Yellow Weasel Spirit for Nine Times, and so on.

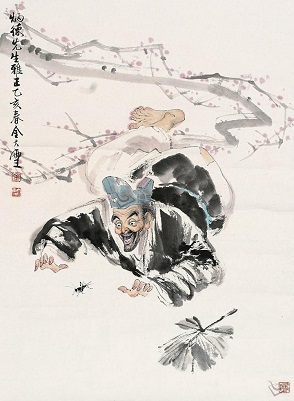

Ji Gong's fascination with crickets

Ji gong, often referred to as the “crazy monk”, was a nonconformist. On figurines of Ji gong, he is often holding a fan, cricket or flask. The fan symbolizes the act of letting negative energy go, and consciously bringing in positive energy. In China , people would put two crickets together and watch them fight. The cricket, in this case, symbolizes the internal battle we have with ourselves. We fight in order to develop our strengths and to understand and transform our weaknesses; it is a spiritual battle, and we aspire to constantly take ourselves to higher levels of understanding, awareness and practice. The flask Ji Gong carries represents non-attachment and the temporal nature of the material world. It is said that while he was alive, he carried around a flask which people presumed was alcohol. However, he could change the liquid to be vinegar, water or another liquid so people were constantly surprised when they drank out of it. Ji gong tried to teach others not to judge anything based on external appearances. He did not care what people looked like, or where they came from. If they had a good heart, he would try to help them. One time, Ji gong and his students were freezing cold and had no way of getting warm. Ji gong tore down the wooden altar they used for worship, and made a fire out of it. One of his students was horrified and cried out, “What are you doing? That's our sacred altar!” Ji gong took the statue of Buddha and cut it into two pieces. The student exclaimed, “You are cutting Buddha! Don't do that!” Ji gong answered, “This statue is not Buddha. This is just wood.” He wanted to teach his students how to let go of material attachments—that what really matters is the True Heart. Wood decays over time; compassion is timeless; it touches people at the deepest level. It was not important to Ji gong whether or not a person appeared to have great virtue: appearances meant nothing to him. He was only interested in the qualities of one's heart.

Monk Ji Gong

http://www.shenyunperformingarts.org/learn/article/read/item/spCxp5EyZws

Ji Gong was born to a wealthy family in the early part of the Southern Song Dynasty. As a young man, he joined a Buddhist monastery and took the name, Dao Ji. Unlike most monks, he dressed sloppily in torn rags and even on occasion ate meat. In short, he was a bit of a character, and his idiosyncrasies irked the other monks. This earned him the nickname “Ji the Crazy Monk,” later shortened to “Master Ji,” or Ji Gong.

Despite his eccentric personality, Ji Gong was sincere, kindhearted, and a well-accomplished follower of the Buddhist teachings. He was known for helping those in need and sometimes even saving their lives. Chinese folk legends fondly describe his various exploits.

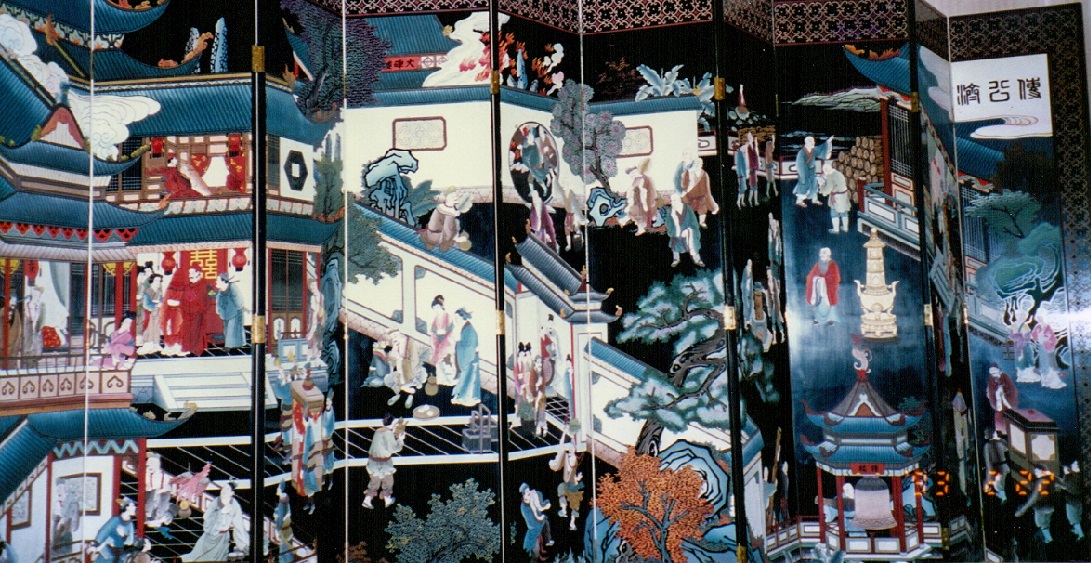

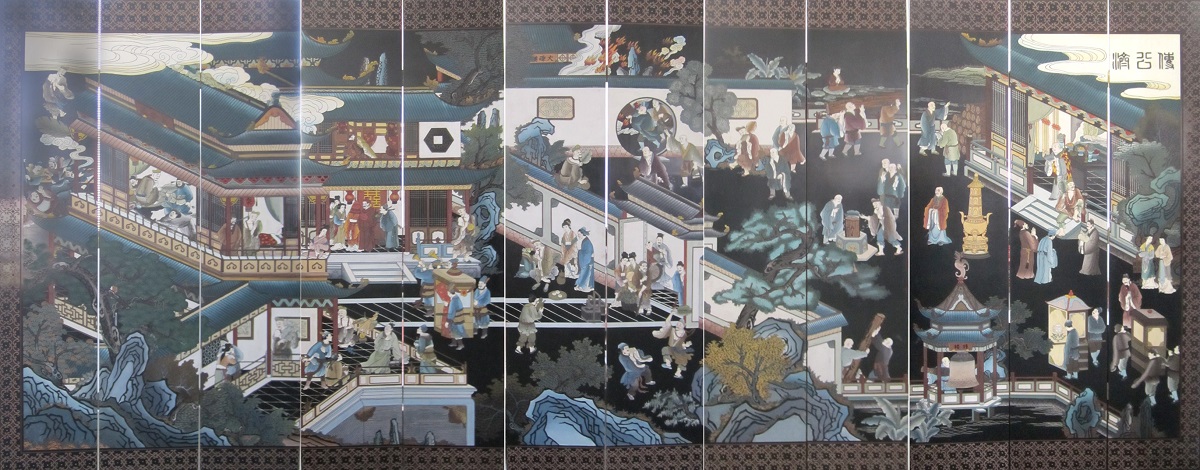

Chinese Traditional Crafts Lacquer Folding Screen.

There are 12 panels in total,

with each panel 40 cm wide by 213 cm high.

(Terebess Collection)

Summoning Logs from a WellOne popular story tells of Ji Gong using paranormal powers to pull logs out of a well. A temple was to be built in Hangzhou and desperately needed wood. The best wood was found only in Sichuan province, some 900 miles away. The monks were desperate.

But that did not stop Ji Gong. He used his powers to bring the logs over one after another. The other monks piled them up, until the monk charged with counting them suddenly shouted: “Enough!” Ji Gong had already beckoned another log, but hearing the monk yell, he stopped it. That last log remained half-submerged in the well, and later generations built a pavilion over it, naming it the “Divine Teleportation Well.”

Stopping a Flying Mountain PeakAnother story, which inspired the Shen Yun dance Ji Gong Abducts the Bride, recounts the monk’s creative ways of rescuing people from imminent danger, even if against their will.

One day, Monk Ji Gong was walking towards Lingyin Temple when suddenly he felt a sudden jolt to his heart. Sensing something amiss, he used his ability of clairvoyance to investigate, and saw that a mountain peak was about to come crashing down on a nearby village.

Alarmed, Ji Gong began shouting to the townspeople, warning them to run for their lives. But they just laughed and dismissed him as “that crazy monk talking nonsense again.” It was then that Ji Gong spotted a wedding procession in the village. He barged in, snatched the bride, threw her over his shoulder, and ran.

Alarmed, the groom and wedding guests called all of their family and friends to chase after the kidnapper. Before long, the entire village was chasing after them.

No sooner had they gone past the village gate than a giant mountain peak nearby collapsed, landing on the village with a crash. Huge rocks flew everywhere, shattering roofs and flattening buildings in an instant.

Ji Gong had rescued the village, but just then he noticed that back in the village a little girl was staggering behind and a gigantic boulder was thundering toward her. He immediately aimed his palm at the boulder and instantly forced it back with his powers, saving her life.

That famous boulder is now called Hangzhou’s “Flying Peak,” and today, visitors can see the imprint of a hand sunk into the base of the rock.

Poetic Leaps in Zen's Journey of Enlightenment

by Zhi, Yong

iUniverse, Bloomington, IN., 2012

A Salvation Story Featuring Ji-gong

We will start the examination with a legendary story about saving a person’s life, featuring Ji-gong, the most colorful Zen eccentric in the history of both Chinese Buddhism and the popular culture:

Once Ji-gong saw an old man trying to hang himself from a tree. The man made a noose and was placing his neck into it when suddenly he saw Ji-gong, dressed in rags, coming his way chanting, “Die, Die, everything is over after I die, death is better than living, I will hang myself now.” Ji-gong also made a noose and looked like he was going to hang himself side by side with the old man from the same tree. The old man was puzzled and asked Ji-gong why he, a monk, would want to commit suicide. Ji-gong told him that he was commissioned to raise money to remodel the monastery. He had begged for three years and collected some money, but on his way back to the monastery, he stopped at a bar, got drunk, and somebody stole all his money. Having no face to go back to the monastery, he decided to end his life. The old man believed his story and said, “Don’t worry, I happen to have some money, which is no use for me anymore.” He gave Ji-gong five pieces of silver, which is all the money he had. Ji-gong took the silver and said, “Your silver does not shine as much as what I used to have, but I will take them.” So he took the money and walked away with a grin on his face. The old man felt even sadder and proceeded his suicide attempt, but Ji-gong returned. The old man thought the monk came back to thank him for the money. But Ji-gong said: “I see you’ve got nice clothing, why don’t you give that to me also so you can nakedly leave this world just as you nakedly came?” The old man was stunned; he looked up the sky and sighed: “Why is it as difficult to die as it is to live, and how can I end my misery?” Ji-gong said, “look, after you die, the wild dogs will come to tear you up, and your nice clothing will be wasted, but if you give it to me, I will make good use of it.” Ji-gong continued to tease and play with the desperate man, until the latter became amused and started to laugh with Ji-gong. The old man soon found this eccentric monk quite friendly and extremely entertaining. He started to open his heart and told Ji-gong his tragic story about the loss of his daughter. His suicidal mind-set miraculously dissolved. Ji-gong helped him to recover his daughter and the story had a happy ending. (Wang 5-8)

Looking at the first part the story, what Ji-gong has done cannot be considered good based on conventions. He shows no pity and sorrow for a desperate man, and even cheats money out of the poor man by fabricating a story. On the other hand, he has successfully intervened a suicidal attempt and saved a person’s life, which is, indeed, not bad. Therefore, what Ji-gong has done in this story cannot be judged on the basis of conventions as either “good” or “bad.”

This story of Ji-gong is a classical example of samadhic play as a Zen’s manner of interaction with others. As discussed earlier, samadhi refers to a non-dualistic state of the mind, and samadhic play is an extraordinary mode of action in which subject and object merge to form a “heavenly flow.” In the samadhic playing with others, the line that demarcates self and others become softened or even dissolved. In the story of saving a suicidal person, Ji-gong, the savior, presents himself as a suicidal man in order to approach another suicidal man. He appears to be even more deplorable and corrupted than the one he is poised to help. In the story, the suicidal man find himself in a situation where he cannot help feeling sympathy for Ji-gong and gives the monk all the money he has. Ji-gong does not approach the suicidal man as a Bodhisattva, the traditional image of the Buddhist savior who always dedicates his compassionate to all suffering beings. Nor does he take a position as a teacher who can preach profound wisdom about life and death. He does not even present himself as a decent person who can show some pity or sorrow for the suicidal man. The roles are dramatically intertwined; the savior takes a position which is even lower than that of the one who is to be saved. The conventional labels, such as the good and the bad, are not apt to speak about Ji-gong’s character and deeds in that story. Regarding the result of the story, Ji-gong not only saves the suicidal person but also uplifts his spirit, although what Ji-gong has done seems to mock all conventional ethical rules. The question is how this samadhic play, the Zen’s way of being with others, can work out a greater good beyond the polarity of good and evil on conventional basis.

First, this samadhic play, as an act of mingling, gives rise to an extraordinary bond between people that can effectively release the sense of alienation people may suffer. In the story, the person attempts to commit suicide because he has lost all his families and feels estranged from society. Part of Ji-gong’s strategy is to build a sense of connection by closing the distance between him and the suicidal man as two strangers so the latter can feel an extraordinary intimacy with people. Suicide can be considered an unethical action, but Ji-gong does not repudiate it, instead, he imitates it. If Ji-gong chooses to approach the suicidal man as a master who takes a position to preach or criticize the latter based on any abstract doctrine, the distance between the two people will increase, and the latter may feel even more alienated.

Second, the story is not only about how Ji-gong intervenes in a suicidal attempt, but also about how the samadhic play gives rise to an event of enlightenment so the suicidal man is saved both physically and spiritually. It seems extremely cruel on the part of Ji-gong to ask the suicidal man to give up his clothing. However, this is one of Zen’s eccentric tactics for shattering a person’s habitual mindset and inducing the experience of emptiness. This tact is similar to a sudden roar projected toward a disciple or a blow on his head with a stick, which is widely used in Zen monasteries. Zen prefers to “directly point to a person’s mind” rather than to preach or criticize a man for his ignorance, because, from Zen’s perspective, enlightenment is not a theoretical understanding but an existential breakthrough or a leap into a new world of consciousness. In order to transform the suicidal person’s view about reality which underlies his suicidal mindset, Ji-gong has to conduct a show in which he plays a clown. A jovial world suddenly unfolds against the background of the desperate situation, in which the suicidal man suddenly feels emancipated from his attachment. The transmission is completed when Ji-gong and the suicidal man start to laugh together. They laugh at each other, at themselves, and at the world.

Ji-gong’s Goodness and Virtuosity

What is beyond good and evil in the spirituality of Zen may not be easily summarized in philosophical statements but can be best illustrated in Zen characters who are able to perform great deeds which cannot be fully reconciled with conventions, whether religious or secular. Ji-gong is the most colorful example of such Zen personalities. Just like the monk Bu-dai depicted in the tenth ox-herding picture, Ji-gong is another legendary monk known as a living Buddha who mingles himself with ordinary people doing good things in eccentric and miraculous ways. People generally believe that Ji-gong was a real person living in the late Sung dynasty. An English encyclopedia describes him as “the dissolute preceptor—a name given him from the dissolute life he led as a monk”(Werner 54). He is portrayed in various literatures as a cheerful and playful monk who often appears to be crazy and drunk, dancing his way to places and joking with whomever he comes across. As exemplified in the above story of saving a suicidal person, he often miraculously comes to peoples’ rescue and fulfills justice in spontaneous and dramatic ways. His performances are enlightening as well as entertaining.

The popular image of Ji-gong is the result of reconstruction by vernacular fictions, movies and other forms of art and media. Shahar, in his work, Crazy Ji, has conducted an extensive textual study about those vernacular fictions of Ji-gong. This popular image of Ji-gong reflects a popular expression of Chinese Buddhism which marks the complete synchronization of Buddhism, Daoism, Confucianism, and the popular culture. The personality of Ji-gong is a manifestation of Buddhist enlightenment, Zhuang-zi’s playfulness, Confucian kindness, and the pragmatic spirit of the popular culture. Indeed, Ji-gong has become a timeless spiritual icon in the mind of Chinese people who see him as a living Buddha, a benevolent god, a divine jester, and a poet.

One way to understand the personality of Ji-gong is to compare him with the traditional Buddhist images of Arhat, Bodhisattva and Zen master. Arhats are the enlightened ones who do not necessarily see interaction with others as a moral or spiritual vocation. They were revered as ascetic saints aloof from the secular world. Ji-gong obviously does not fall into this category since he mingles with all kinds of people. His major activities are in streets and marketplaces rather than in monasteries. There are many hilarious stories about his playfully breaking of monastic precepts, mocking at superior mocks, and performing of various kinds of pranks in monasteries. He is finally dismissed from the Ling-yin Temple, the famous monastery where he became a monk. This monastery remains one of the most famous ones in China partly because Ji-gong is from there. There is a great hall in that monastery hosting the statues of 500 Arhats. Ji-gong’s statue is not among them but right across from them outstandingly in a corridor specially dedicated to him. This arrangement clearly indicates that Ji-gong is not considered one of the Arhats who detaches himself from the worldly life. Indeed, Ji-gong does not take a superior position in his mingling with all sorts of people including those dishonored ones such as thieves, vagabonds, and prostitutes. When he intermingles with corrupted people, he himself appears to be a corrupted person, as in the aforementioned story in which he appears to be a suicidal monk in order to intervene in a suicidal attempt. The mingling with people in such a samadhic manner not only constitutes a practical and expedient strategy to approach people, but also renders an “inner touch” people by successfully dismantling the boundaries that separate them. Hershock believes that Zen’s fashion of interaction with others forms a “liberating intimacy” as a social virtuosity of Zen. As he puts it:

Liberating a sentient being means taking off the mantle of both conceptual and felt distinctions by means of which he or she is individuated or made into some ‘one’ existing apart from others even while in the closest contact with them. (98)

Ji-gong’s intermingling with others, as exemplified in the aforementioned salvation story, not only provides people with practical relief but also forms a samadhic relationship among people, in which the boundaries between people soften. The rapport gives rise to an uplifting “rapture” flowing among people. This relationship is a realization of the collective enlightenment envisioned by Mahayana Buddhism as the “big vehicle” versus the “small vehicle” reflected in the image of Arhat. This samadhic relationship can achieve a sense of harmony which is clearly different from the one envisioned by Confucianism in which harmony is rendered through a hierarchical social structure. Confucianism emphasizes the rectification of social categories and labels that tend to fixate people’s social identity, roles, and status.

The personality of Ji-gong can also be compared with the traditional image of Bodhisattva who is known for his compassion and dedication to the salvation for ordinary people. One of Ji-gong’s well-known titles is “living Bodhisattva.” The term “living” indicates that Ji-gong is different from the symbolic image of Bodhisattva which remains a religious ideal and the object of worship. The traditional images of Bodhisattva, such as Guan-yin, are conceived in Chinese culture as divine being who can answer peoples’ prayers and help them through supernatural ways. Ji-gong obviously does not take such a position as a superior savior, as he mingles and plays with all sorts of people. His compassion for people is human but unconventional. His statue at the Lin-ying Temple fairly captures the complexity of his compassion for people. From one side of the statue, people see Ji-gong laugh graciously, but viewing from the other side of the statue, Ji-gong appears to be sad. Referring back to the aforementioned salvation story, Ji-gong seems to not show any pity and sorrow to the person committing suicide. It appears that all Ji-gong does is to tease and play with the suicidal person until the latter attains a new insight that dissipates the suicidal mindset. The following quote provides a clue for understanding Ji-gong’s compassion for others:

One near enemy of compassion is pity. Instead of feeling the openness of compassion, pity says, ‘Oh, that poor person is suffering!’ Pity sets up a separation between oneself and others, a sense of distance and remoteness from the suffering of others that is affirming and gratifying to the ego. Compassion, on the other hand, recognizes the suffering of another as a reflection of one’s own pain: ‘I understand that; I suffer in the same way. It’s a part of life.’ Compassion is shared suffering. Another near enemy of compassion is grief. Compassion is not grief. It is not an immersion in or identification with the suffering of others that leads to an anguished reaction. Compassion is the tender readiness of the heart to respond to one’s own or another’s pain without grief or resentment or aversion. It is the wish to dissipate suffering. (Kornfield 84)

As illustrated in the salvation story, Ji-gong’s way to dissipate suffering is through a samadhic play which not only involves himself but also those with whom he mingles and interacts. According to Zen, in such samadhic play, the practitioner acts spontaneously following his mind and responding to ever shifting situations, and he can speak spontaneously wherever the spirit of words leads. One who has realized samadhi is emancipated from all conceptual boundaries that enable the division between subject and object, self and others, the religious and the profane, the wise and the ignorant, and the upper and the lower, which forges the “reality” of society. A samadhic player, in his intermingling with others, is able to present them a living show that can immediately and dramatically alleviate them from their old view about their social “reality” to which they are deeply attached.

A Bodhisattva is believed to have the compassion, dedication, and power to deliver people from the samsara world which is full of ignorance and suffering. Ji-gong seems to have no intention to help people with their ultimate salvation from this world. Instead, he tries to mingle with the suffering people and become one of them. In his playing with people, he surely affirms and respects their conventional values and rules, but at the same time kindly laughs at them, and through his playfulness he artistically reveals to people the limitation and transient nature of all conventionally established “reality,” so they may loosen their attachment to it. Ji-gong is completely content with living in this suffering world with “ignorant” people. This agenda is obviously different from the Bodhisattva’s, who wants to deliver people out of this suffering world.

“Zen master” is another title given to Ji-gong, but he is very different from the traditional Zen masters who spent most of their time in monasteries and interacted with their disciples. Without affiliating to any religious institution and assuming any superior moral or spiritual position, Ji-gong does not appear to be a Zen master of any kind. Lai thinks that Ji-gong represents the later period Zen movement which has completed its course of secularization and synchronization with the practical spirit of Chinese culture (143-148). Zen’s coming to streets and marketplaces in embracing the Chinese popular culture is Zen’s final step to liberate itself from doctrines and intellectual frameworks emphasized by traditional Buddhism. This process of secularization and synchronization not only infuses Chinese culture with spirituality but also further transforms Zen by directing its attention to the practical needs in the context of the secular culture. Zen’s spirituality comes to integrate with Chinese literary and performing arts, giving rise to the extraordinary Zen images such as Ji-gong, which is fully developed and circulated in popular forms of Chinese art and media. The joyful spirit of Ji-gong is appropriated by the ordinary people as the source of spirituality, wisdom, and entertainment. Shahar believes that the eccentric character of Ji-gong “offers members of society liberation and relieve (albeit in most cases temporary) from accepted social and cultural norms” (223). Indeed, the eccentricity and playfulness of Ji-gong embodies Zen’s vision of samadhi, which provides people, especially those marginalized, a spiritual way to see through and tackle social injustice and suffering. The following verse are from the theme song of a movie series about Ji-gong’s legendary stories.

Torn sandals, worn hat, shabby monk’s robe . . .

Wherever there is injustice, there I am. (Shahar 163)We label those eccentric Zen figures such as Ji-gong and Bu-dai as poetic not only because they are all poets, but also because their attitudes, deeds, and styles cannot be described, explained, and measured in any conceptual frameworks whether doctrinal or philosophical. For example, we cannot summarize Ji-gong’s attitudes toward social injustice and suffering in philosophical statements. We cannot use conceptual terms such as “positive” or “negative” to pinpoint Ji-gong’s “thought” about conventional rules and values. If we really want to find a word that can capture Ji-gong’s personality, one of the options is “laughter.” Shahar puts it this way:

One element, however, is common to all representations of Ji-gong, in fiction and religious practice alike—his laughter. Be it a novel on Ji-gong, or a spirit-written morality book attributed to him, an actor playing the eccentric god’s role on the sate, or a medium possessed by him—the eccentric god always laughs. (222-223)

The meaning of laughter, however, essentially resists philosophical analysis. Ji-gong’s laughter, just like the one made by Mahakasyapa in the silent sermon given by the historical Buddha, cannot be reduced to conceptual statements. However, Zen’s laughter is the richest and the most accessible sign that inspires and entertains Chinese people of all generations.