ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

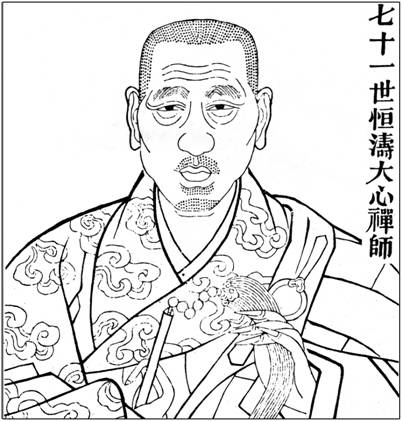

恆濤大心 Hengtao Daxin (1652-1728)

七十一世恆濤大心禪師

恆濤大心 Hengtao (Constant Billows) Daxin (Great Mind) (1652-1728),

Patriarch of the Seventy-first Generation

佛祖道影白話解 Lives of the Patriarchs

宣化上人講於一九八五年八月十六日 Commentary by the Venerable Master Hua on August 16,1985 (宣化 Xuanhua, 1918-1995)

比丘尼恆音 英譯 English translation by Bhikshuni Heng Yin

金剛 菩提海 Vajra Bodhi Sea (VBS): A Monthly Journal of Orthodox Buddhism, No. 350-352.

http://www.drbachinese.org/vbs/publish/350/vbs350p020.htm

http://www.drbachinese.org/vbs/publish/351/vbs351p013.htm

http://www.drbachinese.org/vbs/publish/352/vbs352p013.htm

Text:

The Master was a native of Gutian and had the surname Song. At the age of thirteen, he entered the monastic life under the Elder Dexie of Shangsheng (Ascension) Monastery in his own county. He received complete ordination under the Venerable Xubai of Huangbai. He attended upon the Venerable Lin of Gushan (Drum Mountain) for over twenty years and realized the essentials of the mind. In the year of renwu [1702] during the Kangxi reign period, the Venerable Lin summoned everyone and spoke a verse. Then he entrusted his robe and whisk to the Master and asked him to be the abbot. The Master exerted himself in the practice of ascetism. He was the abbot at Yongquan (Bubbling Spring) Monastery for twenty-seven years. He wore ragged robes, ate coarse food, and joined in to renovate the many dilapidated buildings. He had the style of Great Master Baiz-hang. On the twenty-fifth day of the tenth month in the year of wushen [1728] during the Yongzheng reign period, he manifested the stillness at the age of seventy-seven. His stupa is at Gushan. His works, including Selections from Ancient Times, Recollecting the Ancients, and other verses are still in circulation.Commentary:

Dhyana Master Hengtao (Constant Billows) Daxin (Great Mind) was of the Seventy-first Generation. The Master was a native of Gutian and had the lay surname Song. At the age of thirteen, he entered the monastic life under the Elder Dexie of Shangsheng (Ascension) Monastery in his own county. He left the home-life under the Good and Wise Advisor, Elder Dexie. He received complete ordination under the Venerable Xubai of Huangbai Mountain. He attended upon the Venerable Lin of Gushan (Drum Mountain) for over twenty years. He served as his attendant, taking care of the Venerable Lin's robe and bowl. Sometimes he had quite a bit of spare time, so the verse later says: "Immersing himself in his practice at Bubbling Spring for decades." He quietly applied effort in cultivation and realized the essentials of the mind. Although he was serving as an attendant, he was very vigorous in his own practice and thus became enlightened. Dhyana Master Weilin certified his enlightenment.In the year of renwu [1702] during the Kangxi reign period, the Venerable Lin summoned everyone and spoke a verse. He convened the assembly. That doesn't mean everyone squeezed together. [Note: The words for "summon" and "squeeze" sound similar in Chinese.] If everyone squeezed together and couldn't split up again, what would happen? Dhyana Master Weilin summoned everyone together. (When I explain a word you don't know how to explain, you should pay attention and take notes.) He spoke a verse and then he entrusted his robe and whisk to the Master and asked him to be the successor abbot at Yongquan Monastery. Dhyana Master Weilin, also called Daopei, stepped down from the position and directed the Master to succeed him as abbot.

The Master exerted himself in the practice of ascetism. This Dhyana Master was very diligent in practicing austerities. He was the abbot at Yongquan (Bubbling Spring) Monastery for twenty-seven years. He did not descend the mountain or leave Fujian for forty or fifty years. He always wore ragged robes. "Ragged" means worn out or ruined. As Zi Lu once said, "I will share my horse-driven carriage and light fur coat with friends. I will have no regrets even if my goods are ruined." Zi Lu meant that, "I have a plump horse to ride and a light but warm fur coat that I'm willing to share with my friends. I can use these items, and so can my friends. Even if my possessions are ruined, I wouldn't say anything or be stingy. It's all the same." Here, "ragged robes" means that he didn't wear fine clothing. He also ate coarse food, such as rice mixed with hulls. The Cantonese call it cao mi—coarse, unhulled rice. The rice he ate always had some hulls in it; it was very coarse. He ate what most people would not eat.

And he joined in to renovate the many dilapidated buildings. There were many buildings at Gushan (Drum Mountain) that had fallen into disrepair over the years. When there was work to be done, he would work together with everyone. He wasn't condescending, lording it over everyone, telling them to work and not doing anything himself. He had the style of Great Master Baizhang. His way of doing things resembled that of Dhyana Master Baizhang, Dhyana Master Huaihai. What kind of style was this? Dhyana Master Bai-zhang said, "On any day that I don't work, I will not eat." This Master's style was similar to Dhyana Master Baizhang's

On the twenty-fifth day of the tenth month in the year of wushen [1728] during the Yongzheng reign period, he manifested entering the stillness at the age of seventy-seven. His stupa is at Gushan.

His works, including Selections from Ancient Times, Recollecting the Ancients, and other verses are still in circulation. Nowadays people want to publish their works before they die. In ancient times, people would not have their works published until after their death. Why was this? If their works were published during their lifetime and they gained widespread renown, it would seem like they were seeking fame and benefit. Therefore, in ancient times people would store their writings away, and after they passed away their manuscripts would be discovered and published for them. That's how it was.

Nowadays, as soon as people write something, they want to publish it and put it into circulation immediately. Although it's true that someone might read it and bring forth the resolve for B odhi, it is not too good for the writers themselves. The motives of the ancients are different from those of people today. The ancients feared that their name might become known; modern people fear that others might not know their name. That's where the difference lies. The ancients wanted to be honest and reliable in all they did. Modern people concentrate on superficials and pay attention to appearance. "I'm afraid people don't know about my cultivation, my wisdom, my erudition, and my virtue." They are always advertising for themselves. For example, there's a certain person who had his photo put in the paper, in a full-page ad on the front page, with all kinds of gimmicks. All of these are sterile blossoms that will not bear fruit. He might have temporary success, but it won't last. The false will always come to an end.

Will the truth not perish? The truth will also come to an end. It's not for sure that the truth will always stay around. But the truth, although it comes to an end, is still more worthwhile than the false. The Dharma spoken by the Buddha goes through the Proper Dharma Age, the Dharma Image Age, and the Dharma-ending Age. Yes, the Dharma will come to an end! How can the truth stay in the world forever? It won't. Even so, it still has a different value. By analogy, although gold and copper are both yellowish in color, they are different.

This Dhyana Master lived a frugal and austere lifestyle, devoting himself to others. He stood up and sat down at the same time as everyone else, and ate and drank together with everyone else. He did not have special food cooked separately for himself. In some places when the abbot has money, position, and power, he will eat banquet-style everyday, like an emperor. This Dhyana Master, however, shared the misery and sweetness with everyone else. He didn't have special food served for himself. If he had food different from others', the food was worse, not better. We should realize that this Dhyana Master wore shabby robes and ate coarse food.

He worked along with others in repairing the buildings, and his style was reminiscent of Great Master Baizhang. In his work, Selections from Ancient Times, he selected and compiled a collection of outstanding qualities, characters, and oral teachings from the ancients. In Recollecting the Ancients, he compiled recollections of the moral virtue, erudition, wisdom, and wholesome conduct of the ancients into a book which is still in circulation in the world.

A verse in praise says:

His appearance was stern and awesome.

His conduct was extremely austere.

Coming and going in birth and death,

He dwelt at Snowy Peak and Stone Drum.Commentary:

His appearance was stern and awesome. He had a very forbidding and impressive demeanor. People who saw him would respectfully keep their distance. They were as apprehensive as if they had seen a ghost. His presence was very intimidating. His deportment was quite awesome.His conduct was extremely austere. However, he was very hard on himself. He lived very frugally and austerely.

Coming and going in birth and death. Birth is coming; death is going. He was quite free coming and going, being born and dying. He could do as he pleased.

He dwelt at Snowy Peak and Stone Drum. He cultivated zealously at those two places.

A verse in praise says:Entering madhi in every mote of dust,

He appeared foolish and dull.

Sometimes his brilliance would shine through.

He constantly sang nostalgic praises of the ancients.Commentary:

Entering samadhi in every mote of dust. Every speck of dust was brought about by his samadhi. Every land was a manifestation of his wisdom.He appeared foolish and dull. He seemed like an idiot, like Confucius' disciple Yan Hui.

Confucius said, "Hui seems dumb, for he never opposes what I say. But I examined his behavior after he left and found that he really practiced (what I taught him). Hui is no fool." Confucius said that Yan Hui was not really a fool. As for ignorance, Zeng Seng considered himself ignorant. He was also Confucius' disciple, but was not as smart as Yan Hui. He was dull. "Dull" generally means a little more intelligent than foolish, but here it also means a little more foolish than "foolish." Why? Yan Hui was able to "hear one and know ten." When Confucius explained one principle to him, Yan Hui would be able to understand ten other principles. As for Zi Gong, he would "hear one and know two." When Confucius explained a principle, he could only infer one other principle. As for Confucius' disciple Zeng Seng, he was a bit slow.

Sometimes his brilliance would shine through. Although he appeared foolish and dull, he wasn't truly so. He was simply concealing his light and hiding his tracks. He never showed off or recklessly tried to do things he was not good at. Regarding this point, we should find the Middle Way. We cannot always play dumb with the pretext of not showing off. That's uncalled for. We should neither go too far nor come up short, but should stick to the Middle Way. Maintaining the Middle Way means being the same as everyone else, doing whatever everyone else does. Don't try to show off or act different. If you want to be different from other people, then you aren't even a person.

As human beings, we should be the same as other humans. This Dhyana Master was not truly foolish or dull. He was like a fool; he resembled one, but was not one in actuality. Sometimes his true style would show through; a little bit of his light would shine out occasionally.

He constantly sang nostalgic praises of the ancients. He often chanted verses, the way we chant the "Song of Enlightenment." One chants a line, then pauses to savor its meaning. For example, you recite, "Buddhism in Fujian flourished day after day...Buddhism in Fujian flourished day after day...Buddhism in Fujian flourished day after day." You recite the first line, then think about the second line. It is similar to singing. The ancient scholars would sway their heads as they chanted. This Dhyana Master often chanted verses about the virtuous conduct of the ancients.

Another verse says:

Buddhism in Fujian flourished day after day.

Elder Dexie groomed divine dragons.

He received precepts from Xubai, laying his foundation;

Then he attended upon Weilin,

Causing Drum Peak to quake.

Immersing himself in his practice

At Bubbling Spring for decades,

He extensively propagated the essentials of Dharma;

A thousand lamps were lit in succession.

With awesome demeanor and true practice,

He was an eye for humans and gods.

Yet his original face neither increased nor decreasedCommentary:

This verse does not resemble any fixed form of poetry. It's pure nonsense, composed when I had nothing better to do. The first line goes:Buddhism in Fujian flourished day after day. Fuzhou was Buddhist territory. How can you tell? Because Fujian has Drum Mountain (Gushan), which reminds one of the evening drum and morning bell, which wake people up. The mountain resembled a drum; it would arouse the deaf and startle the blind, waking up confused people.

Elder Dexie groomed divine dragons. At that time there was a Good and Wise Advisor who trained and produced Dharma vessels, dragons and elephants, within the gate of Dharma. They were vessels capable of holding the Dharma.

He received precepts from Xubai, laying his foundation. The Venerable Xubai laid a good, solid foundation for the basic cultivation of Buddhism.

Then he attended upon Weilin. He served at Drum Mountain as the attendant of Dhyana Master Weilin, also known as Daopei, for over twenty years. Causing Drum Peak to quake. Later on, he was like the bird that

Didn't call for three years, and then startled people once it called;

Didn't fly for three years, and then soared to the heavens once it flew.While serving as an attendant, he was quiet and unobtrusive. The Elder Weilin certainly did not praise him to others. You should realize that if you praise a cultivator, others will be jealous of him; if you criticize him, others will scorn him. Therefore, good and wise advisors do not casually praise or criticize people. They do not get involved in praise and criticism, rights and wrongs. At that time, that Dhyana Master cultivated quietly, which means he practiced without people noticing. No one knew he was a cultivator. True cultivators, people with genuine skill, do not advertise themselves. But occasionally his true talent would be revealed, and the peak of Drum Mountain would quake.

Immersing himself in his practice at Bubbling Spring for decades. He practiced quietly by himself in Bubbling Spring Monastery for a long time.

Later, as the abbot, he extensively propagated the essentials of Dharma. When he opened his mouth, people were awestruck. At that point, a thousand lamps were lit in succession. The lamps illumined one another and passed the light on endlessly.

With awesome demeanor and true practice, / He was an eye for humans and gods. His demeanor was stern and majestic, and there was not a bit of hypocrisy in his actions. Therefore, he could be the eyes of human and heavenly beings; gods and people all took refuge with him.

Yet his original face was just that way; it neither increased nor decreased. What is the original face? It is the inherent nature, the Buddha nature which neither increases nor decreases. You could say that he was a Bodhisattva who came back by the power of his vows to guide all of us foolish and immature beings.