ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

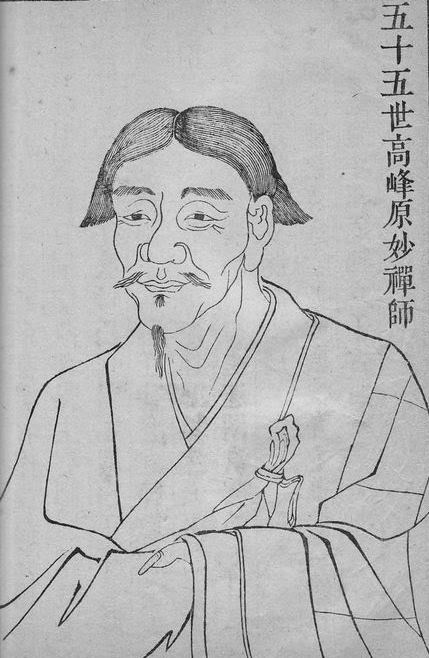

高峰原妙 Gaofeng Yuanmiao (1238-1295)

(Rōmaji:) Kōhō Genmyō

高峰原玅 Gaofeng Yuanmiao

Gaofeng Yuanmiao. (J. Kōhō Genmyō; K. Kobong Wŏnmyo 高峰原妙) (1238–

1295). Yuan-dynasty Chinese CHAN monk in the YANGQI PAI of the LINJI

ZONG. Gaofeng was a native of Suzhou in present-day Jiangsu province. He was

ordained at the age of fourteen and two years later began his studies of

TIANTAI thought and practice under Fazhu (d.u.) at the monastery of Miyinsi. He later

continued his studies under Chan master WUZHUN SHIFAN’s disciples

Duanqiao Miaolun (1201–1261) and Xueyan Zuqin (1215–1287). Gaofeng

trained in Chan questioning meditation (看話禪 KANHUA CHAN), and Xueyan Zuqin

taught him the necessity of contemplating his meditative topic (HUATOU) not

just while awake, but also during dreams, and even in dreamless sleep. (In his

own instructions on GONG’AN practice, Gaofeng eventually used the same

question Zuqin had asked him: “Do you have mastery of yourself even in

dreamless sleep?”) In 1266, Gaofeng went into retreat at Longxu in the Tianmu

mountains of Linan (in present-day Zhejiang province) for five years, of

which he is said to have had a great awakening when the sound of a falling pillow

shattered his doubt (YIQING). In 1274, he began his residence at a hermitage on

Shuangji peak in Wukang (present-day Zhejiang province), and in 1279 he began

teaching at Shiziyan on the west peak of the Tianmu mountains. He subsequently

established the monasteries of Shizisi and Dajuesi, where he attracted hundreds of

disciples, including the prominent ZHONGFENG MINGBEN (1263–1323). He

was given the posthumous title Chan Master Puming Guangji (Universal

Radiance and Far-reaching Salvation). Gaofeng is most renowned for his

instruction on the “three essentials” (SANYAO) of kanhua Chan practice: the

great faculty of faith, great fury, and great doubt. Gaofeng’s teachings are

recorded in his discourse record, the Gaofeng dashi yulu, and his GAOFENG

HESHANG CHANYAO*, better known as simply the Chanyao (“Essentials of

Chan”; K. Sŏnyo), which has been a principal text in Korean monastic seminaries

since at least the seventeenth century. Gaofeng is also known for his famous

gong’an: “Harnessing the moon, the muddy ox enters the sea.”

*Gaofeng heshang Chanyao. (J. Kōhō oshō Zen’yō/Kōbō oshō Zen’yō; K. Kobong

hwasang Sŏnyo 高峰和尚禪要). In Chinese, “Master Gaofeng’s Essentials of

CHAN,” often known by its abbreviated title Chanyao (J. Zenyō; K. Sŏnyo),

“Essentials of Chan.” The text is best known for its exposition of the “three

essentials” (SANYAO) of Chan questioning meditation (KANHUA CHAN): the

great faculty of faith, great fury, and great doubt (YIQING). The text was

republished in Korea in 1399, where it became widely read as a primer on the

practice of GONG’AN meditation. Since the seventeenth century, Korean

Buddhist seminaries (kangwŏn) have included the Chanyao/Sŏnyo as one of the

four books in the SAJIP (Fourfold Collection), the core of the Korean monastic

curriculum.

The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism (2014)

高峰原妙禪師禪要 Gaofeng yuanmiao chanshi chanyao (Essentials of Chan)

高峰原妙禪師語錄 Gaofeng yuanmiao chanshi yulu (Records of Chan Master Gaofeng Yuanmiao)

PDF: The Transformation of Doubt (Ŭijŏng 疑情) in Kanhwa Sŏn 看話禪: The Testimony of Gaofeng Yuanmiao 高峰原妙 (1238-1295).

by

Prof. Robert E. Buswell , Jr.

Halves and Holes: Collections, Networks, and Epistolary Practices of Chan Monks

by Natasha HELLER

in:

Antje Richter, ed., A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture (Handbook of Oriental Studies 4.31) Brill: Leiden, 2015.

The letters of three generations of Chan masters--Gaofeng Yuanmiao 高峰原 妙 (1238-1295), Zhongfeng Mingben 中峰明 本 (1263-1363), and Tianru Weize 天如惟 則 (d. 1354)--provide a window into the epistolary practices of Buddhist monks and the collecting decisions of their disciples. Monks and their disciples wrote letters to reflect on their own spiritual progress and internal state. In response to queries by students, monks also wrote letters to explain Chan teachings. Not all letters were doctrinal in nature: many letters had administrative functions, helping to fundraise or otherwise facilitating the affairs of the monastery. Like letters in the secular realm, monks also wrote letters to affirm social ties and to accompany gifts. For these Chan monks, the social and ritual function of epistolary exchange meant that letters did not represent "entanglements" in the same way that other literary endeavors did.

|

|

|

禪關策進 Changuan cejin [Progress in the Path of Chan]

by 云栖祩宏 Yunqi Zhuhong (1535–1615)

PDF: The Chan whip anthology : a companion to Zen practice

Translated by Jeffrey L. Broughton with Elise Yoko Watanabe

New York : Oxford University Press, 2014.Chan Master Gaofeng Yuan[miao] of [Mt.] Tianmu Instructs the Sangha

pp. 91-96.