ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

傅翕 Fu Xi (傅大士 Fu Dashi,

497-569)

心王銘

Xinwang ming

(Rōmaji:) Fukyū (Fu-daishi):

Shinnōmei

(English:) Mind-King Inscription / Inscription on the Mind King / Faith in the Mind’s Ruler

(Magyar átírás:) Fu Hszi (Fu Ta-si):

Hszin-vang ming

![]()

PDF: The Wind of Compassion

by

Dashi Fu Xi

Translation by White Lotus

Contents

Reflections on the Difficult Road

The Ease of the Road

The Four Appearances

Craving, Aversion, and Delusion

The Two Odes

Returning to the Source

The Floating Bubbles Song

Being Alone

The Watches

Encouragement and Advice

Transcending not Departing

Mind King

Ten Instructions

Six Sections on Frequent Discussions

Mind King Inscription Introduction

The Xinwang Ming (Mind King Inscription)

Diamond Sutra by Mahasattva Fu

A Monk Asked

Preface to the Record of the Great Sage

Record of the Great Sage part 1

Record of the Great Sage part 2

The Biography of Fu Dashi

The Engraved Record of Master Fu

Dashi Fu Inscription

The Record of the Pearl Left Behind

Notice by Lou Zhao

Notice of Longjin Revisions

Zhizhe Dashi

Master Huiji

Master Huihe

Dharma, Master of the Mountain Peak

About White Lotus

References and Resources

Mind-King Inscription

Attributed to Fu Dashi (Mahasattva Fu)

Translated by Jess Row

PRIMARY POINT Summer 2012

http://www.kwanumzen.org/wp-content/uploads/Primary_Point_Summer_2012_small.pdf

(The word ming literally means “inscription,” as an engraving on stone,

or figuratively something that should be preserved in one's heart/mind)

1.

To perceive the mind of the Buddha, the king of emptiness,

is subtle, mysterious and difficult.

Without shape, without any distinguishing characteristics,

Still it has the strength of a great spirit.

It can extinguish a thousand calamities,

And bring about ten thousand attainments.

Although its essential nature is empty,

It reveals all aspects of the dharma.

Look for it and there’s nothing to see,

Call out: you’ll just hear the sound of your own voice.

It is the greatest leader of the dharma,

Its moral strength transmits the teachings.

If water tastes salty,

Only the mind-king can perceive its underlying clarity.

We can see that it exists

Even though we can’t see it in front of us.

The mind-king is exactly like this.

The mind-king stays within the body, unmoving,

and faces the gates of perception, where things come and go.

It adapts to the capabilities of all beings, following every necessity,

Remaining completely at ease, with no obstruction.

But remember: what the mind-king does, anyone can do.

2.

The mind that understands our root consciousness—

That same conscious mind sees the Buddha.

Mind is, so Buddha is.

Buddha is, so mind is.

Every moment possessing Buddha mind—

Buddha mind thinking “Buddha.”

If you want to quickly reach this point

Discipline your mind and control your self.

Pure control, pure mind.

This mind is instantly Buddha.

Apart from the mind-king

There is no other thing that can be called “Buddha.”

If you seek to become a Buddha

Don’t take up any kind of defilement.

Even though mind-nature is empty

Greed and anger are real.

If you want to enter the dharma gate

Sit up straight and become a Buddha.

Then you have already reached the other shore,

And you have attained the paramitas.

The truly re$ned person who seeks the Way

Studies the self, studies the mind,

And knows that Buddha lies within,

Not looking for any other source.

Mind = Buddha.

Buddha = Mind.

This mind-illumination is the real Buddha;

This clear understanding is the real mind.

Apart from mind, no Buddha,

Apart from Buddha, no mind.

3.

“No Buddha” is unfathomable,

There is no adequate way to express it.

If you try to grasp emptiness and get stuck in quietness,

You’ll just keep floating and sinking, floating and sinking.

All Buddhas and bodhisattvas

Lack this kind of “quiet mind.”

A refined person with an illuminated mind

Awakens to this dark and mysterious sound.

The marvelous nature of body and mind

requires nothing more outside itself.

It’s because of this that sages

have free and unobstructed minds.

4.

For the no-word mind-king

Emptiness lacks any substantial nature.

The material body, subject to so many afflictions,

May do harm, or do good.

Not being, and not not-being,

Are neither hidden nor apparent.

Mind nature, apart from emptiness,

May act in a deluded way, or may act with wisdom.

It’s for this reason that I exhort you:

Protect your mind at all costs.

Temples and states can do what they want,

Unstable, floating and sinking.

The pure and clean mind of the sage

Is like gold and jewels in the middle of this world.

The storehouse of the prajnadharma

In this way also exists in the body and mind.

And the dharma treasure of nonaction

Is neither shallow nor deep.

All the Buddhas and bodhisattvas

Already embrace this fundamental mind.

And those who have fully encountered the conditions of the world

Exist beyond past, present and future.

Gâthâs of Bodhisattva Shan-hui (善慧), better known as Fu Ta-shih (傅大士)

Empty-handed I go and yet the spade is in my hands;

I walk on foot, and yet on the back of an ox I am riding:

When I pass over the bridge,

Lo, the water floweth not, but the bridge doth flow.

Translated by D. T. Suzuki (Essays in Zen Buddhism – First Series, p. 272)

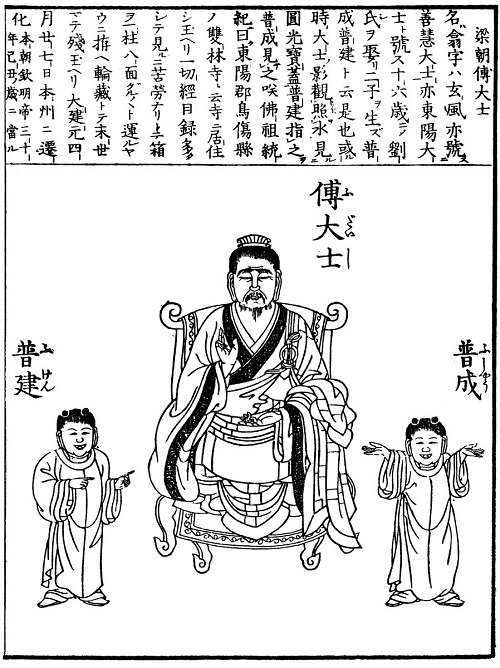

傅大士 Fu-daishi with his twin sons, shown clapping their hands and laughing, are sometimes called Fuwaku (or Fuken 普建・普現) and Fukon (or Fujō 普成・普淨) in Seiryō-ji Temple - Saga Shaka-dō Temple (清凉寺 - 嵯峨釈迦堂), Kyoto

A legend relates, against all the evidence, that Fu-daishi was the inventor of the buildings intended to contain the sūtras. This kyōzō (経蔵) building in Japanese Buddhist architecture is a repository for sūtras and chronicles of the temple history. It is also called kyōko (経庫), kyōdō (経堂), or zōden (蔵殿). A revolving sūtra storage case is called rinzō (輪蔵, wheel repository; rotating libraries). Revolving shelves are convenient because they allow priests and monks to select the needed sūtra quickly. Eventually, in some kyōzō the faithful were permitted to push the shelves around the pillar while praying — it was believed that they could receive religious edification without actually reading the sūtras.

普建, 傅大士, 普成,(Fu-sjoo, Bu-dai-si, Fu-ken), 1852

(Siebold, Philipp Franz von, 1796-1866)

The Motley Bodhisattva

Chapter XIV/26. In: The Golden Age of Zen

by John C. H. Wu

Taipei : The National War College in co-operation with The Committee on the Compilation of the Chinese Library, 1967, pp. 253-254.

The Bodhisattva Shan-hui, better known as Fu Ta-shih, born in 497, was one of the most extraordinary figures in Buddhism and an important precursor of the School of Zen. Once he was invited by Emperor Wu of Liang (who reigned from 502 to 549) to give a lecture on the Diamond Sutra. No sooner had he ascended to the platform than he rapped the table with his rod and descended. The poor emperor was simply lost in amazement. Yet Shan-hui asked, “Does Your Majesty understand?” “I don’t understand at all,” replied the emperor. “But the Ta-shih has already finished his sermon!” Shan-hui remarked.

On another occasion, as Shan-hui was delivering a sermon, the emperor arrived, and the whole community rose to show their respect. Only Shan-hui remained seated without any motion. Somebody took him to task, saying, “Why don’t you stand up when His Majesty has come?” Shan-hui said, “If the realm of the Dharma is unsettled, the whole world would lose its peace.”

One day, wearing a Buddhist cassock, a Taoist cap, and Confucian shoes, Shan-hui came into the court. The emperor, amused by the motley attire, asked, “Are you a Buddhist monk?” Shan-hui pointed at his cap. “Are you then a Taoist priest?” Shan-hui pointed to his shoes. “So, you are a man of the world?” Shan-hui pointed to his cassock.

Shan-hui is said to have improvised a couplet on the occasion:

道冠儒履佛袈裟 With a Taoist cap, a Buddhist cassock, and a pair of Confucian shoes,

會成三家作一家 I have harmonized three houses into one big family!

If, as Suzuki so well says, Zen is the “synthesis of Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism applied to our daily life as we live it,” the tendency was already prefigured in Fu Ta-shih.

Two gathas from Fu Ta-shih have been frequently quoted by Zen masters. One reads:

空手把鉏頭 Empty-handed, I hold a hoe.

步行騎水牛 Walking on foot, I ride a buffalo.

人在橋上過 Passing over a bridge, I see

橋流水不流 The bridge flow, but not the water.

The other reads:

有 物先天地 Something there is, prior to heaven and earth,

無形本寂寥 Without form, without sound, all alone by itself.

能 爲萬象主 It has the power to control all the changing things;

不逐四時凋 Yet it changes not in the course of the four seasons.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Mind Monarch

by Fu Shan-hui (487–569)

Translated by Thomas Cleary

In: Teachings of Zen, Boston & London, 1998

Observe the empty monarch of mind; mysterious, subtle,

unfathomable, it has no shape or form, yet it has great spiritual

power, able to extinguish a thousand troubles and perfect ten

thousand virtues. Although its essence is empty, it can provide

guidance. When you look at it, it has no form; call it, and it has a

voice. It acts as a great spiritual leader; mental discipline transmits

scripture.

Like salt in water, like adhesive in coloring, it is certainly there, but

you don’t see its form; so is the monarch of mind—dwelling inside

the body, going in and out the senses, it responds freely to beings

according to conditions, without hindrance, succeeding at all it does.

When you realize the fundamental, you perceive the mind; when

you perceive the mind, you see Buddha. This mind is Buddha; the

Buddha is mind. Keeping mindful of the buddha mind, the buddha

mind is mindful of Buddha. If you want to realize early attainment,

discipline your mind, regulate yourself. When you purify your habits

and purify your mind, the mind itself is Buddha; there is no Buddha

other than this mind monarch.

If you want to attain buddhahood, don’t be stained by anything.

Though the essence of mind is empty, the substance of greed and

anger is solid. To enter this door to the source, sit straight and be

Buddha. Once you’ve arrived at the other shore, you will attain the

perfections.

People who seek the way, observe your own mind yourself. When

you know the Buddha is within, and do not seek outside, then mind

itself is Buddha, and Buddha is the mind. When the mind is clear,

you perceive Buddha and understand the perceiving mind. Apart

from mind is not Buddha; apart from Buddha is not mind. If not for

Buddha, nothing is fathomed; there is no competence at all.

If you cling to emptiness and linger in quiescence, you will bob and

sink herein: the buddhas and bodhisattvas do not rest their minds

this way. Great people who clarify the mind understand this mystic

message; body and mind naturally sublimated, their action is

unchanging. Therefore the wise release the mind to be independent

and free.

Do not say the mind monarch is empty in having no essential

nature; it can cause the physical body to do wrong or do right.

Neither being nor nonbeing, it is concealed and revealed without

fixation. Although the essence of mind is empty, it can be ordinary

and can be saintly: therefore I urge you to guard it yourself carefully

—a moment of contrivance, and you go back to bobbing and sinking.

The knowledge of the pure clean mind is as yellow gold to the

world; the spiritual treasury of wisdom is all in the body and mind.

The uncreated spiritual treasure is neither shallow nor deep. The

buddhas and bodhisattvas understand this basic mind; for those who

have the chance to encounter it, it is not past, future, or present.

Master Fu Ta Shih

(Literally) Bodhisattva Fu, (alias) Shan Hui

In: Ch'an and Zen Teaching, Series One

by Lu K'uan Yü (Charles Luk)

Rider & Co., London, 1960, pp. 143-145.

Translated from The Imperial Selection of Ch'an Sayings (Yu Hsuan Yu Lu)

[Yuxuan yulu 御選語錄 (Imperial Selections of Recorded Sayings / Emperor's Selection of Quotations)]

(ONE day), the emperor Liang Wu Ti invited master (Fu Ta Shih)

to expound the Diamond Sutra. As soon as he had ascended to his seat,

the master knocked the table once with a ruler and descended from his

seat. As the emperor was startled, the master asked him: 'Does Your

Majesty understand?' 'I do not,' replied the emperor. The saintly master

said: 'The Bodhisattva has finished expounding the sutra.'

(Another day), wearing a robe, a hat and a pair of shoes, the Bodhisattva

came to the palace where the emperor asked him: 'Are you a monk?'

In reply, the Bodhisattva pointed a finger at his hat. 'Are you a Taoist?'

asked the emperor. In reply, the Bodhisattva pointed his finger at his

shoes. 'Are you a lazy man?' asked the emperor. In reply, the Bodhisattva

pointed his finger at his monk's robe.

His gatha read:

The handless hold the hoe.

A pedestrian walks, riding on a water buffalo.

A man passesover the bridge;

The bridge (but) not the water flows.

The following is quoted from 'The Stories of Eminent Upasakas'

(Ch'u Shih Ch'uan) [居士傳 Ju shi zhuan]:

'Fu Ta shi (literally Bodhisattva Fu) was born in the fourth year of

Chien Wu's reign (A.D. 497) in the Nan Ch'i dynasty. He was a native

of Tung Yang district and his lay surname was Fu. Married at sixteen,

he had two sons. At twenty-four, he met one day an Indian ascetic who

said to him: 'You and I took the same vow at Vipasyin Buddha's (the

first of the seven Buddhas of Antiquity) place and your robe and bowl

still remain in the palace of Tusita Heaven. When will you return there?'

The ascetic pointed to a peak and urged him to stay on it to rneditate.

One day, the master had a vision of three Buddhas, Sakyamuni,

Vimalakirti (also called The Golden Grain Tathagata) and Dipamkara,

sending out rays of light to shine on his body. After his realization of

Surangama-samadhi in which all things are perceived in their ultimate

imperturbability, he knew he had attained the ninth Bodhisattva stage,

hence his alias 'Shan Hui'.

Fu Ta Shih was a contemporary of Bodhidharma but both he and the

Indian Patriarch failed to liberate emperor Liang Wu Ti.

The .master's acts of ascending to the seat, knocking the table once and

descending from the seat, were to reveal the Supreme Reality expounded

in the Diamond Sutra. His was the best way of revealing the pure and

clean mind inherent in every man, which is responsible for all common

acts of daily life.

One day he presented himself at the palace to enlighten the emperor.

In olden times as well as in our modern age, people attach great importance

to the outward appearance of a man as well as to his academic titles and

social standing. All this having no value in relation to the Buddha

Dharma, Fu wore a hat, a monk's robe and a pair of shoes, to wipe out

all conceptions of form, appearance, aspect and characteristic as taught

in the Diamond Sutra. A monk usually wears no hat, a Taoist no shoes

and a layman no monk's robe.

The first gatha which the Bodhisattva composed to enlighten his

disciples was:

Each night, (one) embraces a Buddha while sleeping,

Each morning, (one) gets up again with him.

When rising or sitting, both watch and follow one another,

Whether speaking or not, both are in the same place,

They never even for a moment part,

(But) are like the body and its shadow.

If you wish to know the Buddha's whereabouts,

In the sound of (your own) voice, there is he.

This gatha reveals that the self-natured Buddha is inherent in every

man and never leaves him. Fu Ta Shih's teaching was in line with that of

Buddhas and Patriarchs and his first gatha directly pointed at everybody's

mind. Its simplicity, however, soon gave rise to doubts and suspicions

in the minds of his disciples who wanted something more abstruse. He

was, therefore, compelled to compose his second gatha which read:

There is a thing preceding heaven and earth,

It has no form and is in essence still and void.

It can master all things in this world

(And) follows not the four changing seasons.

This second gatha is not so clear and simple as the first one. The thing

that precedes heaven and earth is the eternal nature which is immaterial

and imperceptible. It produces all appearances but does not change in the

midst of the changing phenomenal. This gatha especially pleases scholars

who like its poetic form, but soon people, whose minds would wander

outside in constant search of something new and sensational, began to

cast it aside and looked for something extraordinary to satisfy their desires

for emotional things. Hence, the third gatha presented in the above text.

The first line of the gatha means: the handless mind uses its phenomenal

human form which is endowed with two hands, to hold the hoe.

The second line means: the phenomenal man has a mind inherent in

him, which directs his two feet to walk.

The man's act of passing over the bridge reveals that which enters his

body at birth and leaves it at death.

In the fourth line, the bridge, or human body, is always changing

whereas the water, or the self-nature, is immutable and never changes.

It is very regrettable that this gatha has given rise to discrimination in

the minds of some modern commentators who like to link it with Albert

Einstein's Theory of Relativity which has no place in the Mind Dharma.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

平等實性

The True Nature of Equality

An empty hand, grasping a hoe.

On foot riding a water buffalo.

People crossing a bridge,

The bridge is flowing, the water is not.

...

四相詩

Poems on the Four States

I. Birth

Relying upon the ovum, consciousness arises, birth arises from love and desire.

In a time now past he grew up, today he returns as a child.

The stars follow the cycle of human life, red lips open for milk.

Because we are deluded to our true Dharma nature, we still suffer in the cycle of birth and death.

II. Old Age

Look into the mirror and see how your face has changed, how climbing the stairs can take your strength.

You let out a sigh: now you are old, going forward to bow, still your body is lacking.

Your body is like a tree grown near a precipice; your mind is like a sea turtle longing for the ocean.

Still indulging in your outflows, yet unwilling to study the unconditioned Dharma.

III. Sickness

Suddenly you contract a fatal illness, and because of this, become bedridden.

Wife and children are silent and sad, friends dislike being near you.

You suffer—pains in thousands of veins, groaning so that the entire neighborhood hears.

Not knowing the dangers that lurk ahead, you still indulge in desire and anger.

IV. Death

Consciousness bids farewell to life, a wandering spirit enters the gates of death.

Countless numbers have departed—I have not seen a single person return.

The favored horse waits with a shrill neigh in vain, the flowers in the courtyard will no longer be picked.

Hurry and seek the supreme Way and avoid the four sufferings.1

1: Literally “the four mountains,” a reference to the four masses of suffering mentioned in the poem: birth, old age, sickness, and death.

...

十勸

Ten Admonishments

I admonish you once:

Focus the mind and be always mindful of the paramitas.1

Diligently practice the six perfections to attain bodhi,2

Thus you will go beyond the five impurities and the three lower realms.3

I admonish you a second time:

Men are not to renounce the world to seek benefit.

Even if such seeking gains something for a time,

Not long from now, you will return to Haoli.4

I admonish you a third time:

As this human body is difficult to obtain, you should feel shame for your faults.

Day and night, throughout the six time periods,5 be always mindful of the Buddha,

Diligently cultivate the Triple Gem,6 and go to the temple.

I admonish you a fourth time:

Strive to do what is good.

Do not say you are young, strong, or bright;

When the end comes, where will you go?

I admonish you a fifth time:

Think of the bitterness of hell.

Those who seem rich and noble and appear dignified,

Will, at a time not long from now, return to the land.

I admonish you a sixth time:

It is most important not to eat the flesh of sentient beings.

If it be not a bodhisattva7 manifest,

Then it is family from a past life.

I admonish you a seventh time:

There is nothing more important than the truth.

One who says “three” in the morning yet “four” in the evening is not a good person;

When his life comes to an end it will not be fortunate.

I admonish you an eighth time:

The people who eat meat are truly evil spirits.

In this life, if you take the life of another,

In a future life you will be killed.

I admonish you a ninth time:

Heaven and hell clearly exist.

So do not offer wine and meat to a monastic,

Or you shall spend five hundred lifetimes without hands or feet.

I admonish you a tenth time:

Admonish one another to practice with urgency.

Once your life is over you will travel the yellow river8—

Father, mother, wife, and child, crying in vain.

1: Virtues which lead to liberation. Also called the “six perfections.”

2: Enlightenment.

3: The five impurities of time, views, afflictions, beings, and life, and the realms of hell, hungry ghosts, and animals.

4: Reference to a fabled cemetery in the southern foothills of Mount Tai, but also more generally used to refer to the land of the dead.

5: A Chinese system of time division which divides the day and night into six periods each. These periods encompass the entire day.

6: The Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.

7: A Buddhist practitioner who has vowed to become a Buddha to liberate living beings. Bodhisattvas that have progressed far in their practice are said to be able to assume any form to teach others.

8: Another name for the Chinese underworld.Translated by John Balcom (After Many Autumns, 2011)

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Empty-handed I go, but the spade is in my hands;

I walk on my feet, yet I am riding on the back of a bull;

When I pass over the bridge,

Lo, the bridge, but not the water, flows!Translated by Garma C.C. Chang (The Practice of Zen, 1959, p. 16.)

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Grasping in his empty hand the spade,

and riding on his buffalo,

the farmer crosses a bridge.

It is the bridge which flows away behind him, not the water.Translated by R. D. M. Shaw (The Embossed Tea Kettle, 1963, p. 83.)

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Empty-handed, but holding a hoe;

Afoot, yet riding a water buffalo.

When the man has crossed over the bridge,

It is the bridge that flows and the water that stands still.Translated by Philip Yampolsky (The Zen Master Hakuin, 1971, p. 60.)

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Empty-handed, holding a plow:

Walking, riding a water buffalo:

When the man crosses the bridge,

The bridge flows and the water does not.Translated by Trevor Leggett (Three Ages of Zen: Samurai, Feudal and Modern, Charles E. Tuttle, Tokyo, 1993. p. 96.)

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

With the hoe grasped in his empty hands,

His hiking is as if his riding on the buffalo.

And when a man walks across the bridge,

The bridge is flowing, yet the water isn’t.Translated by Wang Lushi

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

A younger contemporary of Bodhidharma, the famous "Mahasattva" (great saint) Fu, is another figure of prominence in the traditions of early Zen Buddhism. Some of his sayings remained favorites of later Zen practitioners. One of those unusual people whom Zen tradition refers to as "responsive manifestations," who are not known to have received teaching from a human mentor but were enlightened through inspirations resulting from their practices, Mahasattva Fu was a philanthropist with a considerable following that included his wife and children as well as other relatives.

A literate farmer, Fu expounded Buddhism to the emperor Wu of the Liang dynasty, and the record of his sayings and deeds is one of the richest sources of teachings surviving from among the early adepts. Perhaps the most famous of his utterances prized in Zen tradition in his verse:

Empty-handed, holding a hoe,

Walking, riding a water buffalo.

Man is crossing a bridge;

The bridge but not the river flows.

The first two lines illustrate the familiar theme in developed Buddhism of being in the world without clinging to things of the world, employing ways and means without becoming possessively attached to them. The second two lines illustrate the contrast between objective and subjective reality: "thusness," naked reality without the screen of mental construction, is in flux (as a river) but does not really change, in that it is always "as is." The mental structures used in crossing over the world, on the other hand, that is, the viewpoints, conceptions, and interpretations are rooted in subjectivity and undergo fluctuation and change, even if they are fixed from their own point of view.

The realistic approach according to this teaching, therefore, would be to recognize the functional value of structures as tools and vehicles, but to also recognize their temporary nature and refrain from attachment to them even while using them. This permits contact with wider reality and freedom to adapt to changing conditions without the impediment of clinging to the familiar or habitual for its own sake. Thus in one single verse Mahasattva Fu summed up a central issue of Buddhism.

Mahasattva Fu is not associated with a particular lineage but is believed to have received the transmission from reality itself through the medium of certain experiences.

By Thomas Cleary (Book of Serenity. Lindisfarne Press, 1990. pp. xvi-xvii.)

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

![]()

Fu Hszi (Fu Ta-si) verse

Terebess Gábor fordítása

Művészet, XXII. évfolyam, 7. szám, 1981 július, 4. oldal

Folyik a híd, 1990, 7. oldal

Üres a kezem, mégis kapál,

Gyalog járok, 's bivalyháton,

Megyek a hídon, és azt látom:

Folyik a híd, a víz meg áll.

Hamvas Béla fordítása

In: Az ősök nagy csarnoka II. Kína - Tibet - Japán, Medio Kiadó, 2003, 351. oldal

Üres kézzel vándorolok, s kezemben bot van,

Gyalog ballagok, s ökör hátán megyek,

Amikor a hídon áthaladok,

Íme, nem a víz folyik, hanem a híd repül.