ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

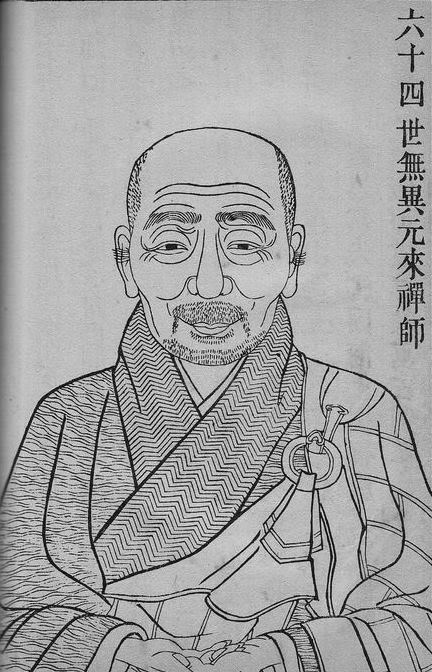

無異元來 Wuyi Yuanlai (a.k.a Dayi 大艤 1575–1630) [博山 Boshan]

博山和尚參禪警語

Boshan heshang canchan jingyu

(Rōmaji:) Mui Genrai (a.k.a Daigi) [Hakusan]:

Hakuzan osho sanzen keigo

(English:) Boshan [“Mount Bo”]

Tartalom |

Contents |

Jeff Shore

|

示疑情发不起警語 Shi yi qing fa bu qi jing yu 示疑情发得起警语 Shi yi qing fa de qi jing yu PDF: Great doubt: practicing Zen in the world / Boshan

Chan Buddhist Meditation Dhyana Master Wuyi Yuanlai |

Boshan (1575-1630) was one of the leading Chinese masters of the Ming dynasty. Boshan, or Mount Bo, is the name of the mountain where he was active; like many masters, he became known as such. He is also known as Wuyi Yuanli and Dayi.

Boshan hailed from Shucheng in present-day Anhui Province, west of Nanjing. He left home in his mid-teens, took up Buddhist study and practice, including five years of sustained meditative discipline, and received full ordination. Later he practiced under the Caodong (Japanese: Soto) master Wuming Huijing (1548-1618), a severe teacher who persistently rejected Boshan’s intial insights. One day, while sitting intently in meditation on a rock, Boshan had a sudden realization when he heard a statue nearby fall with a crash. The following year he was greatly awakened when watching a person climb a tree. He was in his late-twenties at the time. Boshan received the Bodhisattva precepts before teaching at several monasteries, finally settling at Mount Bo in present-day Jiangxi Province, south of Anhui. He was one of Wuming Huijing’s four Dharma heirs, and he himself left behind several Dharma heirs and lay disciples. He passed away in 1630.

禪病警語 Chanbing jingyu

無異元來禪師廣錄 Wuyi Yuanlai chan shi guang lu

Record of the Chan Teacher Wuyi Yuanlai

博山和尚參禪驚語 PO-SHAN HO-SHANG TS'AN-CH'AN CHING-YU (Japanese, Hakuzan osho sanzen keigo), in two chuans, Dainihon Zokuzokyo, 2.17.5 (pp. 473b-486a). The admonitions to Zen students before and after they have attained satori, short commentaries on the words of old masters, and verses, by monk Wu-i Yuan-lai (Japanese, Mui Genrai) (1575-1630) of the Ts'ao-tung Tsung, compiled by the head monk (shou-tso) Ch'eng-cheng 成正首座 (Japanese, Josho shuso)."Discourses of Master Po-Shan," translated by Garma C. C. Chang [Chang Chen-chi], in The Practice of Zen (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1959), pp. 66-79. Thirty-one passages taken from the above late Ming (1368-1644) work--about one-fourth of the complete text--and given in their original sequence.

More recently, Sheng Yen's Attaining the Way: A Guide to the Practice of Chan Buddhism (Boston: Shambhala, 2006) includes excerpts translated by Guogu (Jimmy Yu), pp. 19-22.示疑情发不起警語

Exhortations for Those Unable to Arouse the Doubt

Great Doubt: Getting Stuck & Breaking Through the Real Koan; in: Jeff Shore: Zen Classics for the Modern World: Translations of Chinese Zen Poems & Prose with Contemporary Commentary, Diane Publishing Co. 2011, 138 p.

http://beingwithoutself.files.wordpress.com/2011/07/great_doubt.pdf示疑情发得起警语

Exhortations for Those Who Do Rouse the Doubt

Jeff Shore: "The first four of his Exhortations for Those Who Do Rouse the Doubt. Here he shows what happens when the Great Doubt is aroused, and some of the problems that can occur. This can be a great help as your practice matures and comes to fruition."

http://beingwithoutself.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/exhortations-for-those-who-do-part-1.pdf

http://beingwithoutself.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/exhortations-for-those-who-do-part-2and3.pdfChan Buddhist Meditation

by Boshan Wuyi

Translated by Thomas Cleary

Kindle Edition, Sep 17, 2015

69th Generational Patriarch Dhyana Master Wuyi Yuanlai

虛雲老和尚集 Composed by the Elder Master Hsu Yun

宣化上人講於一九八五年六月十三日 Commentary by the Venerable Master Hsuan Hua on June 13, 1985

Vajra Bodhi Sea, No. 306. November 1995.

http://www.drbachinese.org/vbs/publish/306/vbs306p011.htm

The Master was born to the family of Sha in Shu City. He studied under Dhyana Master Shouchang and investigated the topic of a place to hide away without a trace, whereupon he had an awakening.

Dhyana Master Chang said, “Ants are attracted by foul odors, and flies always head for stinking places. Does this have to do with the king or the minister?”

The Master replied, “It has to do with the minister.”

Dhyana Master Chang reproached him. Hearing the statue of the Dharma protecting spirit fall to the ground with a crash, he was suddenly enlightened. He composed a verse and submitted it, but Dhyana Master Chang refused to acknowledge it. One day he went to the toilet, saw someone climbing a tree, and had a great awakening. He went to see Dhyana Master Chang, who interrogated him. The Master answered each of the questions confidently. Dhyana Master Chang said, “Now you know that I have not been cheating you.” In the year of renyin , he became the Abbot at Boshan. Later he served as Abbot at Dongyan, Dayang, and Gushan . In the year of Jisi, he went to Tianjie in Jinling, where he sought instruction and practiced the Way for thirty years. Because he deeply respected the great Dharma, many eminent men drew near to him, but he did not lightly give his approval to anyone. He manifested the stillness at the age of fifty-eight in the year of gengwu during the reign of Chongzhen . A stupa was erected for him on the mountain.

This is the 69th generational patriarch, Dhyana Master Wuyi Yuanlai. His name Wuyi means “no different.” No different from what? He was no different from common people, and no different from the Buddhas. The mind, the Buddhas, and living beings are no different from one another. Yuanlai means “it was originally so.” The Master was born to the family of Sha in Shu City in the province of Anhui. His lay surname was Sha. His father was Sha He, and he had a brother named Sha Hai.

He studied under Dhyana Master Shouchang and investigated the meditation topic of a place to hide away without a trace, whereupon he had an awakening. He gained a little insight. Dhyana Master Chang engaged in verbal combat with him and said, “Ants are attracted by foul odors, and flies always head for stinking places.” Ants instinctively gather at foul-smelling places. Blue-bottle flies are bluish-green in color and may grow as large as a person's fingernail. They will fly to wherever there is a stench.

“Does this have to do with the king or the minister?”

The Master replied, “It has to do with the minister.” When someone asks a question like that, you shouldn't answer. If you answer, you fall into his trap. If you say it has to do with the king, he can say it has to do with the minister. If you say it's the minister's business, then he'll say it's the king's business. It's not fixed. He can make a reasonable argument for either side. No matter what you say, he can say the opposite and make you seem in the wrong. You wouldn't be able to make head or tail of the situation. That's how verbal sparring works. If you don't answer his question directly, but rather reply with something totally different, then you can get out of the dilemma. Dhyana Master Chang reproached him because he fell into the trap.

No matter who questions you, you don't have to answer right away. Your reply has to be flexible. Your questioner might want you to give a logical answer. Ha! Logic! Don't think of questions in Chan as being fixed. Whatever can be spoken has no real meaning. As soon as you say it, it's wrong. “Once you open your mouth, you've made a mistake. Once you give rise to a thought, you are off.” Then why did the Dhyana Master question him? Because he still had to resort to language in order to test his student. He wanted to see if he really understood, if he was an expert.

“Does this have to do with the king or the minister?” This question is like when those quack fortune-tellers say, “ Fu zai mu xian wang .” [Note: This ambiguous sentence can mean either “The father is alive and the mother has passed away” or “The father passes away before the mother.”]

Suppose a fortune-teller tells you that and you say, “Oh, my mother has passed away, and my father is no longer alive.”

“Of course, I told you that your father passed away before your mother,” he would say.

And if you say, “Actually, my mother is still alive, and my father has passed away.”

He would then say, “Of course, I told you clearly that your father passed away before your mother, and your mother is still alive.”

Therefore, when the Dhyana Master said, “Ants are attracted by foul odors, and flies always head for stinking places,” how did that have anything to do with the king or the minister? His question was completely groundless. I have only one comment: Nonsense!

Vajra Bodhi Sea, No. 307. December 1995

http://www.drbachinese.org/vbs/publish/307/vbs307p011.htm

From last issue:

Dhyana Master Wuyi Yuanlai studied under Dhyana Master Shouchang. Dhyana Master Chang engaged in verbal combat with him, saying, “Ants are attracted by foul odors, and flies always head for stinking places. Does this have to do with the king or the minister?”

He just made up this topic so he could have something to talk about, that's all. When the Master replied, “It has to do with the minister,” he got scolded. Hearing the statue of the Dharma protecting spirit fall to the ground with a crash, he was suddenly enlightened. Whether it was because the spirit no longer wanted to protect the Dharma or for some other reason, the statue fell to the ground, and he suddenly became nlightened. He composed a verse and submitted it, but Dhyana Master Chang refused to acknowledge it. He wasn't necessarily seeking for approval; he just wanted Dhyana Master Chang to take a look and see if he was right. However, the Dhyana Master refused to certify him. In fact, he totally ignored him.

One day he went to the toilet, saw someone climbing a tree, and had a great awakening. He was so anxious that he didn't know what to do or where to turn. Then he went to the toilet and saw a person climbing a tree. At first he thought it was a monkey, but a closer look revealed that it was a man. And so he had a sudden great awakening. He went to see Dhyana Master Chang, who interrogated him. Dhyana Master Shouchang cross-examined him, and the Master answered each of the questions confidently. He gave prompt answers to every question, without stopping to think or consider. His replies were righteous and full of confidence.

Dhyana Master Chang said, “Now you know that I have not been cheating you.” Dhyana Master Shouchang certified him and said, “Today you finally know that I haven't cheated you. Maybe you didn't understand that before. You know now what all those beatings and scoldings I gave you were for. I wasn't bullying you without reason.”

In the year of renyan, he became the Abbot at Boshan. Later he served as Abbot at Dongyan, Dayang, and Gushan monasteries. In the year of Jisi, he went to the capital, Jinling, where he sought instruction and practiced the Way for thirty years. He was there for more than thirty years. Because he deeply respected the great Dharma, many eminent men drew near to him, but he did not lightly give his approval to anyone. Many outstanding people went to study under him. However, he didn't casually bestow praise upon people.

He manifested the stillness at the age of fifty-eight in the year of gengwu during the reign of Chongzhen at the end of the Ming dynasty. A stupa was erected for him on the mountain. His pagoda was built on Bo Mountain.

A verse in praise says:

At a place where there were no tracks,

he suddenly tripped and fell.

As he wondered why someone was climbing a tree,

the bucket's bottom dropped off.

He won over the multitudes and seemed to be

Master Shao come again.

The Master's teaching was exalted;

in ten thousand years he stood out alone.Commentary:

At a place where there were no tracks, he suddenly tripped and fell. “Fell” means he was scolded. When he replied that it was the minister's affair, that was equivalent to tripping and falling. As he wondered why someone was climbing a tree, the bucket's bottom dropped off. When he saw someone climbing up the tree, he got enlightened. The bucket refers to a bucket of black paint, which represents ignorance. Now the bucket has been broken; its bottom is gone.

He won over the multitudes and seemed to be Master Shao come again. It was as if National Master Shao had returned to the world. National Master Shao had probably been very eloquent, and so people admired his wisdom and oratorical skill. The Master's teaching was exalted. Dharma Master Yuanlai's Way-places were very strict, with very high standards. In ten thousand years he stood out alone. He set a distinctive course, which stood firm in the world.

Hsuan Hua's verse says:

Living beings, the mind, and the Buddhas are not different.

Seeing someone climb a tree, he came back to life.

Termites are instinctively drawn to foul odors.

Flies know only to head for stinking places.

The king, minister, assistant, and envoy trade places.

Old or young, noble or lowly, all must escape the net.

Great people who can transform themselves are sages.

Riding on his vows, he returned to save the Saha world.Commentary:

Living beings, the mind, and the Buddhas are not different. This Dhyana Master was the same as living beings, the mind, and the Buddhas. Seeing someone climb a tree, he came back to life. He'd been like a dead person, investigating his Chan topic to the point that the heavens and earth became dark and north, south, east, west, the intermediate directions, and the zenith and nadir were all forgotten. Yet when he saw someone climbing a tree, he was suddenly enlightened; he came back to life.

Termites are instinctively drawn to foul odors. Termites, without having to be taught, know where to look for putrid things. Flies know only to head for stinking places. They always fly to foul-smelling areas. Who taught them to do that? Whose affair is it? Is it the affair of the king, the minister, the assistant, or the envoy? The king, minister, assistant, and envoy trade places. In Chinese medicine, the king, minister, assistant, and envoy assist each other; their roles are interchangeable.

Old or young, noble or lowly, all must escape the net. All people have to extricate themselves from the net of mundane defilements, whether they are honorable or lowly, old or young. Great people who can transform themselves are sages. All great wise advisors are sages come again. Riding on his vows, he returned to save the Saha world. Based on the power of his past vows, he returned to the Saha world to teach and transform living beings. He came looking for a few people who understood his heart, but perhaps he didn't find any and returned in disappointment.

Chan Buddhist Meditation

by Boshan Wuyi

Translated by Thomas Cleary

Kindle Edition, Sep 17, 2015

Introduction

Chan Buddhism is known as the school of “direct pointing to the human mind, to see its essence and realize enlightenment.” The fundamental technique employed to produce this result is called reversing attention to look back, meaning to turn attention away from the contents of the mind to focus on the essence of awareness itself. The aim is to attain independence, free from the influence of external indoctrination and internal compulsion. There are many traditional sayings and stories used to promote this process, both directly by fostering this mental posture, and indirectly by clearing the mind of distracting thoughts. In addition, there are some works especially devoted to describing procedures and problems of Chan meditation, including the use of sayings and stories.

The text translated here follows on many centuries of Chan practice and experience. The author, Chan master Wuyi (1575-1630), commonly known as Boshan after a place where he taught, was one of the most distinguished Buddhist teachers of the late Ming dynasty in China. The Ming dynasty had been founded by a leader of a millenarian movement who subsequently sought to contain and control Buddhism institutionally to prevent the rise of similar movements. Chinese Buddhism, as well as Taoism and Confucianism, had already suffered stagnation under the repressive regime of Mongol warlords during the preceding dynasty, so Chan was in a critical state of decline by Boshan's time. This gave rise to the practice of meditation intensives, periods of special concentration intended to break through the institutional accretions and spiritual lethargy of the times.

Warnings to Beginners doing MeditationDoing meditation first requires a firm determination to break through birth and death, seeing through the world, the body, and the mind as all conditional, with no real autonomy. If you don't discover the great principle inherent in you, then the mind being born and dying will go on uninterrupted, the murderous demon of impermanence will not stop for a moment. Then how can you fend it off?

Use this one thought as a piece of brick to knock on the door. Be as if you were sitting in a bonfire, trying to get out. You might take a step at random, but you can't halt in your tracks. You can't think of anything else, and you can't seek help from anyone else.

At such a time, you can only plunge straight ahead without worrying about the fire, without worrying about yourself, without looking for someone to help, without having another thought, unwilling to delay for a moment.

If you can get out, you're skillful.

In doing meditation, it's important to develop wondering. What is wondering? For example, you don't know where you came from when you were born, so you can't help wondering where you came from. You don't know where you go when you die, so you can't help wondering where you're going.

When you can't break through the barrier of birth and death, wondering arises at once. It coalesces before your eyes, so you can't set it down or chase it away.

Suddenly one day you break through the mass of wonder. Then the words birth and death are useless furniture.

An ancient adept said, “Wonder a lot and your awakening will be great; wonder little and your awakening will be little. If you don't wonder at all, you won't ever wake up.”

When doing meditation, stick the word death on your forehead; regard your flesh and blood body and mind as if dead, just keeping the thought of seeking enlightenment before you.

This thought is like a long sword hanging in the air. If you touch the blade, it cannot be grasped. If you clear away obstruction and whet the blunt, the sword is long lost.

When doing meditation, most of all beware of addiction to a state of quietude. That causes people to stagnate in lifeless silence, unawares and undiscerning.

People get tired of activity but not stillness. If seems to me that travelers are always in places where there is a lot of commotion, so once they experience a state of quietude it is like eating candy or honey. It is like people wanting to sleep when they're tired out. How can they know themselves?

Other religions mortify their bodies and minds, turning them insensate; they also seek entry by way of quietude. It seems to me that over years and years of deadening and desensitizing, and silencing and stilling, one will deteriorate into an ignoramus, no different from an inanimate object.

We sometimes resort to states of quietude, but it is only to awaken understanding of the momentous event of being.

This only works if you are not cognizant of being in a state of quietude. If you look for any semblance of stillness in the momentous event of being, you cannot find it at all. This is attainment.

When doing meditation it is essential to be centered, balanced, and strong enough to detach from the human condition. If you react emotionally, then you won't be able to do meditation. Not only will you be unable to do it; eventually you'll wind up following a commonplace preacher, without a doubt.

When you do meditation, you do not see the sky when you look up, you do not see the ground when you look down. When you look at mountains they're not mountains, when you look at rives they're not rivers. When you walk you don't know you're walking, when you sit you don't know you're sitting. In the midst of a crowd you don't see a single person. Your whole being, inside and out, is just one single mass of wondering.

This can be called homogenizing the world. The key to meditation is the commitment not to stop until the mass of wonderment breaks.

What does homogenizing the world mean? The universal principle that has always been there has never stirred, absorbed in silence and stillness. What is required is for the person concerned to rouse the spirit, so that the sky revolves and the earth turns, finding within oneself the capacity to make waves.

When doing meditation, don't fear ‘dying' and being unable to come to life; just fear living without being able to ‘die.'

If you are able to stay right with the feeling of wonder, states of agitation will spontaneously disappear without having to be dispelled. The wondering mind will spontaneously be clear without having to be cleared. All the senses will naturally be open, immediately effective and responsive—why worry about not coming to life?

When you're meditating efficiently, it's like carrying a half-ton load that you can't put down even if you try, like looking for something essential that's been lost, unwilling to relax until it's found. Just don't get fixated, infatuated, or philosophical—fixation produces sickness, infatuation produces bedevilment, and philosophizing produces cultism.

When you actually attain single-mindedness and total concentration, it is like looking for something lost. Then those three types of problems melt into irrelevance. As it is said, if you excite the mind and stir thoughts, you turn away from the substance of reality.

In doing meditation, when you bring a saying to mind, you must be thoroughly clear, like a cat catching a mouse. An ancient referred to this when he threatened to kill a cat if no one could say anything appropriate.

Otherwise, if you sit inside a ghost cave, completely immersed in utter darkness all your life, what's the benefit of that?

When a cat is getting ready to pounce on a mouse, even if there is a chicken or a dog nearby the cat pays no attention, because it's only intent on catching the mouse. Those who practice Chan should also be like this: it's just a matter of determination to understand this principle, such that no matter what happens you don't have time to pay any mind. The moment you have any other thought, not only do you lose the mouse, but even the cat as well.

When doing meditation, each day you should see what you have accomplished that day. If you waver and vacillate, you'll never be done.

Once I set up a stick of incense, then when I saw it had finished burning, I said, “My meditation is like before, no change. How many sticks of incense do I consume in a day, how much incense in a year?” I also said, “Time flies and waits for no one. If I haven't understood the great matter yet, when will I be done?” I used this painful regret to drive myself.

When you do meditation, don't try to figure out cases of the ancients and misinterpret them. Even if you do get the gist of each one, it's got nothing to do with your self. You still don't realize that each word of the ancients, each saying, is like a bonfire that you can't get near and can't even touch, much less sit or lie down in it. Of those who go on and differentiate the major and minor among them, discoursing on high and low, few will not lose their lives.

This affair does not conform to doctrinal approaches, so even those who have practiced the Great Vehicle for a long time don't recognize it—how much less those in the lesser vehicles. Don't the three ranks of the wise and the sages in the ten stages understand the doctrines? Yet if you expound this one affair, those in the three vehicles are terrified, those in the ten stages are startled; even the bodhisattvas at a stage equivalent to enlightenment, whose teaching is like clouds and rain, liberating inconceivable numbers of people and initiating them into acceptance of the truth of no origin, are still said to suffer from the folly of knowledge, in total violation of the Way—how much more so the rest!

As this is a matter of going from the state of the ordinary person to immediate identification with buddhahood, it is hard for people to believe. Those who believe it have the capacity for it; those who don't believe don't have the capacity. Practitioners who want to enter into this religion all enter through faith.

Faith may be shallow or deep, false or true—it is imperative to distinguish. As for the shallow, who would say they don't believe in the religion they have joined? Yet they just believe in the religion, not in their own mind. As for the deep, even the bodhisattvas of the Great Vehicle don't have this faith.

As a commentary on the Flower Ornament Scripture says, “If your view is that there is someone who expounds the teaching and a group that listens to the teaching, you have not yet entered the door of faith.”

If you say “mind is Buddha,” who would say they don't believe? Then when you ask “Are you Buddha?” they dismiss it and don't accept it. The Lotus Scripture says, “If they used all their thinking to assess it collectively, they could not measure the Buddha's knowledge.” Why? If your mind uses all its thinking power assessing, that's just because you don't have faith.

As for false and true, “one's own mind is Buddha” is called true faith, while grasping something outside of mind is called false faith. “Being Buddha” requires examination and clarification; “one's own mind” is personally experienced in real life. When you reach the state where you have no doubt, only then is it called true faith. If you presume upon assumption and supposition, just saying “mind is Buddha” without actually knowing your own mind, that is called false faith.

The ancients practiced concentration while picking peaches, practiced concentration while hoeing the earth, and were also concentrated while doing chores. So how could it be accurate to refer to concentration as coming after sitting for a long time suppressing the mind to keep it from activity? If you do it this way, it's called false concentration; it is not the true purpose of Chan.

The Sixth Grand Master said, “A dragon is always in concentration.” You need insight into fundamental essence in order to attain this concentration. Shakyamuni Buddha descended from the heaven of satisfaction into a royal palace, went into the Himalaya Mountains, saw the morning star, and enlightened deluded masses, all without ever leaving this concentration. Otherwise one would be overwhelmed by states of activity—how could that be called concentration?

In the midst of activity, when you look for where it originates you cannot grasp it. In the midst of stillness, when you look for where it originates you cannot grasp it either. Since activity and stillness have no point of origin, how can they be states? If you understand what this means, everything is one single mass of concentration, filling everywhere, all-pervasive, all-inclusive.

When doing meditation, don't stick to things of the world; don't even stick to anything in Buddhism, much less worldly things. If a saying is truly and correctly present before you, you walk on ice without feeling cold, walk through fire without feeing heat, pass right through a thicket of brambles without sensing any obstruction. Only then can you act freely in the midst of the things of the world. Otherwise, you'll be turned around by objects, and never be able to attain total concentration.

People doing meditation should not search through literature seeking phrases and memorizing words. It's not only useless, it obstructs meditation, as real meditation reverts to conditioned thought. Then how can you attain quiescence of mental activity?

When doing meditation, what is to be feared most is conjecture. Try to focus your mind consciously on it, and you become even further from the Way. Even if you do this until the future Buddha Maitreya is born in earth, you will simply miss the point.

If the sense of wonder suddenly arises, it fills the universe; you don't even know there is a name for the universe. It is like sitting between a silver mountain and an iron wall; how can you be at peace if you don't find a way to live? Just keep working this way, and when the time comes there will naturally be a resolution.

In recent times some false teachers keep students from constant effort, even claiming the ancients never made effort. This statement is most poisonous, misleading youth so they go to hell like an arrow shot.

Chan Master Dayi's Poem on Sitting Meditation says, “Don't believe those who say you don't need to concentrate; the ancient sages labored to point the way. Even if you're going to be free as you once were, have you yet won the right?” Those who say they get the principle without needing concentrated search, calling it the inherent Maitreya and the natural Shakyamuni, are to be pitied. Never having done a concentrated search themselves, they happen to see stories of ancients attaining enlightenment at once with a question and an answer, and then they interpret this subjectively, even fooling others. If they come down with a serious fever one day that has them screaming to the heavens, their usual interpretations won't be of any use. When they reach the end of their lives, they'll be like lobsters plunged into a pot of boiling water—what will be the use of regret?

Chan Master Huangbo said, “To transcend worldly toils is not a common affair; grip the rope firmly and give it a try. Unless the cold pierces your bones, how can the plum blossoms smell good to your nose?” These words are extremely considerate; if you use these lines for inspiration from time to time, your meditation will get done naturally.

It's like a journey of a hundred miles; with every step you take, that's one step less. If you don't go, but just stay here, even if you can talk about your home and work quite thoroughly and clearly, still you never reach home, so what do you actually accomplish?

In doing meditation, what is most critical is intensity. Intensity is most powerful. Without intensity, you become lazy. When you become lazy, you become negligent and indulgent.

If you apply your mind with genuine intensity, where can negligence and laziness come from? You should know the significance of intensity. Don't worry that you won't reach the state of the ancients, don't worry that you won't break through your fluctuating mind. Seeking Buddhism without this intensity is all foolish, crazy external pursuit; how could it even be mentioned on the same day as meditation?

Intensity not only frees you from excesses; you immediately transcend goodness, badness, and indifference. When you concentrate on a saying very intensely, you don't think of good; when you concentrate very intensely, you don't think of bad; when you concentrate very intensely, you don't fall into indifference. When the saying is intense, there is no agitation or excitement; when the saying is intense, there is no torpor or oblivion; when the saying is foremost in your mind, you don't fall into indifference.

Intensity expresses utmost attentiveness. When concentration is attentive, that means it has no gaps; so bedevilment cannot get in. When concentration is attentive, you do not conceive of notions such as existence or nonexistence, so you don't fall into deviated ways.

People doing meditation don't know they're walking when they walk, don't know they're sitting when they sit. This is called having a saying foremost in mind. As long as the sense of wondering isn't broken through, you don't even know you have a body and mind, much less whether you're walking or sitting.

When doing meditation, beware of musing to compose poems, verses, or other literary work. If your poems and verses are accomplished, you may be called a poet, and if your compositions are skillful you may be known as a writer, but this has nothing to do with seeking Chan.

Whenever you encounter conditions that stir thoughts, whether unpleasant or pleasant, immediately become aware of it and bring up a saying, not letting yourself be affected by surrounding conditions. Some people say, “Don't be strict.” These three words seriously mislead others; students have to be careful.

When doing meditation, people often fear falling into a void. When a saying is foremost in mind, how can that be void? This fear of falling into a void itself cannot be voided; how much less a saying foremost in mind!

When doing meditation, if the sense of wondering isn't broken through, it's like being on the edge of an abyss, or walking on thin ice; the slightest loss of mindfulness and you perish.

Because the feeling of wondering isn't broken through, the great principle isn't apparent. When your breath stops, your whole life is brought forth in the in-between state, and you cannot avoid going along with consciousness conditioned by action, changing faces unawares and unknowing.

So add wonder to wonder; when you bring up a saying, determine to understand what you haven't understood, determine to break through what you haven't broken through. It's like catching a thief; you've got to see the loot.

When doing meditation, don't consciously await enlightenment. It's like walking along a road; if you stand in the road waiting to get home, you'll never arrive—you have to walk to get home. If you consciously await enlightenment, you'll never be enlightened; you have to press on to bring about enlightenment.

When you attain great enlightenment, it is like a lotus suddenly blooming, like suddenly waking up from a long dream.

When you're dreaming, you're not waiting to wake up. When you've slept sufficiently, then you wake up naturally. A flower does not anticipate blooming; when the seasonal time comes, it blooms naturally. For enlightenment, you don't expect enlightenment; when the conditions are met, you naturally become enlightened.

I say that for conditions to be met, what is important is pressure to cause awakening through the intensity of a saying. This isn't awaiting enlightenment.

Also, when you're enlightened, it's like opening the clouds to see the sky, infinitely vast, resting on nothing. The sky revolves, the earth turns, yet this is still a temporary state.

Doing meditation requires strictness, correctness, attentiveness, and fluidity.

What is strictness? A person's life is in between exhalation and inhalation. Before you've understood the great matter, once you stop breathing in, the road ahead is unclear and you don't know where you're going. You cannot but be strict. An ancient adept said, “It's like hemp sandals when they get wet—they get tighter with every step.”

What is correctness? Students should have the perceptivity to distinguish truth. There is much in the way of examples from the three thousand seven hundred Chan masters; if you deviate in the slightest, you enter a false path. Scripture says, “Only this one actuality is true; anything else is not real.”

What is attentiveness? You lock brows with cosmic space, so closely that a needle could not be stuck in, water poured on could not wet, not allowing the slightest gap. If there is the slightest gap, then bedeviling experiences will invade through the gap. An ancient adept said, “Any time you're not present, it's as if you're dead.”

What is fluidity? When the world is ten feet wide, the ancient mirror is ten feet wide; when the ancient mirror is ten feet wide, the furnace is ten feet wide. You do not get fixated, dwelling on one point, holding a dead snake fast. Neither do you get tied down to duality, with no direction and no stability. An ancient adept said, “Completeness is like cosmic space, with no lack and no excess.” To really attain fluidity, inwardly do not see you have a body and mind, outwardly do not see there is the world; only then will you gain access.

If you are strict but not correct, you will misdirect effort. If you are correct but not strict, you cannot gain access. Once you're gained access, you have to be attentive to be in tune. Once you're in tune, you need fluidity. Only then are you in a state where it's possible to learn.

When doing meditation, you cannot apply any other thought at all. When on the go, standing still, sitting around, or lying down, just bring up the saying you're contemplating over and over, arousing a sense of wondering, determined to find a resolution. If you have any other thought, this is what ancients called mixed poison entering the mind. Not only does it harm physical life, it harms spiritual life. Students have to be careful.

I say “other thought” doesn't refer only to things of the world. Outside of examining mind, everything good in Buddhism is called “other thought.” And is it only things in Buddhism? All grasping and rejecting in the substance of mind, all clinging and influence, is called “other thought.”

Doing meditation, many people say they can't do it effectively, then keep on doing it ineffectively. It's like when someone doesn't know the road, he should find out; he shouldn't just say he can't find the road and simply quit. Now when he has found the road, the important thing is to get going, proceeding straight home. It won't do to stand there on the road; if you don't move, you'll never get home.

When doing meditation, do it to the point where there's nowhere to apply the mind, to the edge of a ten thousand fathom cliff, to where the rivers and mountains end. Like a mouse going into a horn, there will naturally be a conclusion.

When doing meditation, beware of cleverness. Cleverness vitiates the medicine. If you get into it at all, even if the real medicine is there it can't help you. Real students of Chan should be as if blind and deaf; as soon as a thought arises, it's like bumping into a silver mountain, an iron wall. Only if you meditate like this are you in tune.

When you do meditation with genuine intensity, you forge body, mind, and the material world like an iron bar. When it snaps, you have to get it together again.

In doing meditation, don't be afraid of making mistakes; just be afraid of not realizing when you're wrong. Even if your practice is in error, as soon as you recognize it's wrong, that is the foundation for becoming enlightened, a key route out of birth and death, a sharp instrument to cut through the net of bedevilment.

Shakyamuni Buddha experienced the Hindu methods, but he didn't stick to them; the words “knowing what's wrong, give it up” lead directly from ordinary humanity to the stage of sagehood. And this doesn't apply only to the transcendental—in worldly things there is loss of mindfulness; it only takes “knowing what's wrong and giving it up” to become an impeccable person.

If you embrace an error rigidly and therefore will not acknowledge it's wrong, then even a living Buddha couldn't help you.

When doing meditation, don't avoid noise and seek quiet, shutting your eyes and making a living sitting in a ghost cave. This is what ancients called sitting at the foot of a mountain of blackness, soaking in the water of stagnation—what does it accomplish?

You simply must work in the context of the conditions of the environment; this alone is where you gain strength. With a saying set on your eyebrows, as you walk, as you sit, as you dress and eat, as you meet people, all you want to do is clarify the point of this saying.

One morning as you wash your face you'll come across your nose—it was so close all along! Then you can save energy.

Doing meditation, beware of taking the conscious spirit for the activity of buddhahood. You may raise your brows and twinkle your eyes, shake your head and revolve your brains, thinking it all quite marvelous; but if you do things with the conscious spirit, you cannot even be a servant of the Hindus.

Doing meditation, what is actually required is for mental activity to cease; don't try to focus the mind on thinking about dialogues or stories. Dongshan said, “Try to understanding subtleties, and you lose the source; in terms of potential, you are ignorant of process.” Then it's no use talking to you.

When you penetrate the universal principle, every single spiritual state flows from your own mind. This is farther from creations of thought than sky from earth.

When doing meditation, don't fear you can't do it successfully. When you can't do it effectively, wanting to do it is itself meditation. An ancient adept said, “No door is the door of liberation; no idea is the idea of the wayfarer.” The important thing is to find your way in; if you beat the drum of retreat when you can't manage to do it at once, then no amount of time, however long, will be enough for you.

When a feeling of wonder has arisen that you can't put down, then you're on the road. Stick the words life and death on your forehead and proceed as if a tiger were chasing you—if you don't run right home, you'll lose your life. Can you still afford to tarry?

When doing meditation, just concentrate on one case; don't make intellectual interpretations of all the cases. Even if you can interpret them, this is interpretation, not enlightenment. The Lotus Scripture says, “This truth is not accessible to thought.” The Scripture of Complete Enlightenment says, “Trying to measure the realm of the complete enlightenment of the realized is like trying to burn the Polar Mountain with the fire of a firefly—it can never be done.” Dongshan said, “If you try to use ideas to study mysticism, that's like heading east to go west.” Anyone who looks into the cases must have blood under the skin and know when to be ashamed.

Doing meditation, bringing up a saying, just be aware you haven't broken through the sense of wondering, with no second thoughts—don't go to scriptures and literature for testimonies, engaging the cognitive sense. Once the cognitive sense is activated, arbitrary thoughts race in profusion. If you want to attain what is beyond words and mentation, how can you do it that way?

The Way is not to be left for even a moment; what can be left is not the Way. Meditation is not to be interrupted for even a moment; what can be interrupted is not meditation. True seekers are as if their brows were afire, as if they were saving their heads from burning. What leisure is there to stir thoughts about other things? An ancient adept said, “It is like one individual facing ten thousand enemies; staring them in the face, what leeway is there to blink?” This saying is essential for doing meditation; it is imperative to know it.

Doing meditation, as long as you haven't broken through yourself, you can only handle your own concerns—you cannot teach others. It's like someone who's never been there telling others about the capital city; not only does he fool others, he fools himself too.

Doing meditation, one dare not slack off morning and night, like the great master Ciming, who used to stick himself with an awl when he was about to doze off at night. The ancients even went without food and drink for the sake of the Way; what kind of people are we?

An ancient drew a circle on the ground with lime and declared he would not leave the circle as long as he had not understood the principle. Nowadays people indulge their wishes and whims, dissolute and unbridled; they call it being lively, but that is just a laugh.

Doing meditation, you may have feelings of lightness and ease, or you may have flashes of insight. Don't consider this enlightenment.

In the past, I contemplated the Boatman's saying about having no tracks. One day as I was perusing the Transmission of the Lamp, I read Zhaozhou predicting to a monk, “You'll get it when you meet someone three thousand miles away.” Unawares I lost my cloth sack; it was like putting down a thousand pound load. I thought this was great enlightenment, but then when I met Baofang it was like putting a square peg in a round hole; then I was full of embarrassment and shame. If you don't see a great teacher after awakening, even if you attain ease you will still not be done.

Baofang encouraged me to further effort with a verse:

When emptiness meets emptiness, that's no great feat;

When being follows being, the virtue's still slight.

There's criticism of Kasyapa's peace with biology;

Where the advantage is gained, the advantage is lost.This is an expression of “atop a hundred foot pole, take a step forward.” Chan practitioners have to comprehend this.

I once told a student, “I got Baofang's two words ‘I disagree' and found no end of use for them.”

Doing meditation is not to be understood theoretically. Just keep at it, and only thus will you arouse the sense of wondering. Theoretical understanding is totally dry—it cannot solve the issue of the self. It cannot even arouse the sense of wonder.

Suppose someone asks what's in a container, and it's not actually what is indicated to him. He takes what's not so to be so, and thus cannot wonder about it. Not only can he not wonder—he confuses one thing for another. Until he opens the container and looks, he'll never be able to tell what it is.

Doing meditation cannot be understood as having no concern. Just determine to understand this matter. If you understand by having no concern, all your life you'll just be an unconcerned person, and never finish with the one great concern inside your clothes.

It's like looking for something you've lost; you're not finished till you find it. If you set it aside in the realm of unconcern when you can't find it, and have no will to look for it, even if the lost item showed up you wouldn't see it, simply because you're not looking.

Doing meditation cannot be understood in flashes. If you have flashes that come and go, what's the use of that? If you want to personally experience real practice, you have to see for yourself. If you really and truly get the meaning, you're as certain as when seeing your own parents in broad daylight. There's no greater joy in the world.

Doing meditation cannot be figured out intellectually; thinking and figuring prevent meditation from becoming concentrated, so you can't develop the sense of wonder. Thinking and figuring obstruct true faith, practice, and perception; students should regard them as enemies.

Doing meditation, don't think you get it just by engaging. If you think you get it, that is precisely what is meant by being fat-headed. Then you are not in tune with the search.

Just develop a sense of wondering, to foster penetration of mental freedom where there is nothing to get and no one to get it, like a castle in the air. Otherwise, you're taking a thief for a son, taking the servant for the master. An ancient adept said, “Don't take a donkey-saddle ridge for your late father's lower jaw.” That's what this means.

Doing meditation, don't look for people to explain it all for you. If someone explains, that is after all another's—it has nothing to do with your own self.

It's like asking someone the way to the capital—just have them point out the road, don't go on and ask about things in the capital. If someone explains things in the capital one by one, after all that will be what that person has seen, not what the inquirer sees. That is how it is when you don't make effort but immediately ask for someone to explain everything.

Doing meditation is not just a matter of mentally repeating cases. You can repeat them until the end of time, and it will still be irrelevant. Why not mentally repeat the name of the Buddha of Infinite Light instead? That would be more beneficial.

I am not simply telling you that you don't need to repeat them mentally—you can still bring up sayings one by one. For example, if you contemplate the word “No,” then you wonder about “No.” If you contemplate the “oak tree,” then you wonder about the “oak tree.” If you contemplate “Where does the One return?” then you wonder about where the One returns.

When you manage to arouse the sense of wonder, the whole universe is a mass of wonder. You don't know you have a physical body—your whole body is a mass of wonder. You don't know the universe exists—it is not inside or outside; they're merged into one mass. Just wait till it comes apart, and then see a teacher.

The important business is done without anything being said. Then you'll clap your hands and laugh. Looking back at repeating cases, you see it was like a parrot learning to talk. Why have anything further to do with it?

When doing meditation, don't lose right mindfulness for a moment. If you lose the thought of inquiry, you'll drift into different views and forget to come back.

For example, if someone sitting in a state of purity just delights in clarity, stillness, and considers absolute transparency to be the work of a Buddha, this is called losing right mindfulness and falling into clear stillness.

Some focus on that which speaks and converses, that which is active and still, considering this the concern of Buddhas. This is called losing right mindfulness to acknowledgement of the conscious spirit.

Some try to suppress the wandering mind, considering the inactivation of the wandering mind to be the work of Buddhas. This is called losing right mindfulness to suppress the wandering mind by means of the wandering mind, like a rock on grass. It's also like stripping plantain leaves; strip off one layer, and there's another layer—there's no end to it.

Some visualize body and mind as like empty space, not producing thought, like a wall; this is called losing right mindfulness. Xuansha said, “If you try to freeze your mind, rein in thoughts, resolving everything into emptiness, you are a nihilist, a corpse that hasn't given up the ghost.”

All of this is because of losing right mindfulness.

Doing meditation, when the sense of wonder is successfully induced, then it must be broken up. If you can't break it up, you must make right mindfulness firm and true, unleash a great vehemence, and add intensity to intensity.

Jingshan said, “If sturdy folks want to find out this important matter, let them break through superficial appearances, straighten their spines vigorously, and not go along with human sentiments. Take what you've been wondering about and stick it on your forehead; then be just like a man deeply in debt being pressed for payment but lacking the wherewithal, fearing to be shamed; getting a sense of urgency and importance where there was none, only then will you get into the spirit of the thing.”

Zhaozhou said, “For thirty years I didn't mix attention. Only dressing and eating were mixed attention.”

This doesn't mean not being attentive, just not mixing attention. This is what is meant by the saying that you can do anything when you focus on one point.

Zhaozhou said, “Just investigate the principle. Sit and contemplate for twenty or thirty years, and then if you don't understand, cut off my head.”

Why is Zhaozhou in such a dead hurry? Even so, years and months are long—if you look for those whose determination doesn't change for twenty or thirty years, they are hard to find.

Zhaozhou said, “When I was eighteen years old I already knew how to break up the home and squander the inheritance.”

He also said, “I used to be used by the twenty-four hours; now I use the twenty-four hours.”

When you make a living on the family inheritance, you're used by the twenty-four hours. When you disperse the family inheritance, you use the twenty-four hours.

If someone asked what the family inheritance is, I'd say, “Remove the skin bag and I'll tell you.”

Zhaozhou said, “If you spend your life in a Chan community, even if you don't talk for five or ten years no one will call you dumb. Later on even a Buddha will not be able to handle you.”

“Not speaking” means “not mixing attention.” If you don't investigate the principle in yourself, you're still far away.

National Teacher Shao of Tiantai said, “Even if you can give answers and analyses fluently, that just makes for upside-down knowledge. If you only value answers and analyses, what's so hard about that? I'm only afraid they have no benefit for people, instead becoming deceptive.”

People of the present time who learn some superficials are always asking questions, making Buddhism a plaything. It's not only useless, it's often pernicious. Yet nowadays they indulge in idle talk, as if it were the vehicle of religion; in light of what the ancient said, they are quite shallow and insensitive.

The National Teacher said, “In what the elders have been studying—analysis, dialogue, and anecdote—they speak a lot about theory. Why aren't their doubts laid to rest? When they hear of the expedients of the ancients, they don't understand at all, simply because they themselves are not very genuine.”Analysis and anecdote belong to conditioned thought, so fluctuation doesn't stop. How can the intent of the ancients be understood that way? This is why it is said, “When subtle words linger in the mind, it turns back into a site of conditioned thought; reality is right before the eyes, but it turns into a realm of names and forms.”

The National Teacher said, “It's better to see through at once from where you stand; see what the principle is. How many teachings have created doubts for you? When you seek to understand, then you realize that what you have learned up till now is just a source of birth and death, living inside the body-mind clusters and elements of sense experience. That is why an ancient said, ‘If perception isn't shed, it's like the moon in the water.'”

Who doesn't have perception and thought? What is necessary is to go through great transformation. If you do not tune in with meditation, but try to tunnel through a crystal palace, you'll never connect. An ancient adept said, “When intellectual interpretation gets into the mind, it's like oil in flour; it can never be removed.” You have to be careful.

Chan Master Shaoyan said, “Good people, the ruler of the nation has invited me to speak today, only hoping you will clarify your minds; there is no other reason. Have you clarified your mind? Now when you are conversing, when you are laughing, when you are silent, when you are visiting teachers, when you are having discussions with colleagues, when you are enjoying natural scenery, and when your ears and eyes have no objects, is this your mind? Interpretations like these are all demonic possession—how can it be called clarifying mind?”

Speaking is not it, silence is not it; seeing and hearing is not it, detachment from seeing and hearing is not it either. How do you understand?

Right now meditators should not set to work in confusion.

Shaoyan said, “There is another kind of person who, apart from illusions about the body, separately takes the whole universe, including the sun and moon and cosmic space, to be the original true mind. This is also a non-Buddhist idea. It is not clarifying the mind.”

This is called the heresy of biased emptiness. How can you attain oneness of body and mind, so there is nothing outside the body? Followers of Chan today who try to be their own masters without meeting anyone else often fall into this view.

Shaoyan also said, “Do you want to understand? Nothing is the mind, yet nothing is not the mind. If you try to grasp it and affirm it, can you succeed?”

The preceding two statements referred to unhealthy states, whose flaw is in grasping and asserting. This statement is medicine—if there is no insistence or denial, no grasping or assertion, the illusion is then cured.

Chan Master Ruilu said, “Study doesn't necessarily mean learning to question sayings, or learning to analyze sayings, or learning to make alternative statements, or learning variations of sayings, or learning to pick out extraordinary expressions from scriptures and treatises, or picking out extraordinary sayings of Chan masters. You may master studies like these as much as you please, but you'll still have no perception when it comes to Buddhism. Such people are said to have sterile intelligence. Haven't you heard, ‘Intellectual brilliance doesn't fend off birth and death; how can sterile intelligence free you from the cycle of suffering?'”

People today are all like this, throwing away gold to pick up rubble. Unwilling to really investigate, they spout off verbally. Xiangyan, for example, could give ten answers to one question, and a hundred answers to ten questions—isn't this masterful? Yet he had no Buddhist perception, and was stymied by the expression before your parents conceived you. Those of the present time who study words, tell me—what does it accomplish?

Ruilu said, “If you're going to study Chan, it must be truly genuine study before you can succeed. When you're walking, study while walking; when you're standing, study while standing; when sitting, study while sitting; when sleeping, study while sleeping; when speaking, study while speaking; when silent, study while silent; when working, study while working. Now when you're studying at such times, tell me—who are you studying from? What statement are you studying? At this point, you must experience clarity yourself before you can succeed. Otherwise, you'll be a dilettante, and never realize the ultimate meaning.”

You should look intensely into this “What statement are you studying? Who are you studying from?” If you don't find out this statement and don't know who this is, you're wasting your time, not studying Chan.

Baqiao said, “Suppose someone is traveling along when he comes to a deep hole, just as a wildfire is advancing on him from behind. On both sides are thickets of brambles. If he goes forward he falls into the pit, if he goes back he gets burned in the fire, and if he turns to either side he is blocked by brambles. At that moment, how can be escape? If he can escape, he has a way out; if not, he is fallen dead.”

You can only get through if you disregard danger and death; as soon as you hesitate, you perish. This saying of Baqiao is critical for meditation. Students often seek conceptual understanding, falling into the clichés of mysticism, not paying attention to here. This is called a waste of a life.

Yunmen said, “There is a kind of pilferer of vanities who consumes others' slobber, memorizes a bunch of antiques, and runs off at the mouth wherever he goes, boasting he can pose five or ten questions. Even if you pose questions morning till night until the end of time, will you ever have had perception, even in a dream?”

In those days, Yunmen was criticizing one or two out of ten; in today's medley of confusion, everyone is like this. When have they ever studied with their very being? Even if they may sit for a while, they're either oblivious or distracted. That is because the desolation in their gut can't be spit out and can't be cut off. If you are sharp, you will have to be very conscientious the moment you hear such a quotation before you can get it.

Yunmen said to a group, “Don't pass the time taking it easy; you must be very thoroughgoing. The ancients had a lot of sayings to help you. For example, Xuefeng said, ‘the whole earth is your self.' Jiashan said, ‘Pick me out in the hundred grasses; recognize the emperor in a bustling market place.' Luopu said, ‘The moment a particle appears, the whole world is contained in it; every hair is the whole body of the lion.' Take these up and ponder them over and over; eventually, after a long time, you will naturally gain access.”

These three sayings lead you to the door, for you to enter at will. If you don't, you're all making a living in a ghost cave. If you can enter the door, you'll naturally be at peace, not seeing that there are mountains, rivers, and earth, not seeing that there is your own self. Picking out and not picking out are dualistic expressions.

Yunmen said, “When the light doesn't penetrate freely, there are two kinds of illness. When everywhere is not clear and there seems to be something there before you, that is one. Also, when you manage to penetrate the emptiness of all things and yet subtly there seems to be something, this too is failure of the light to penetrate freely.

“The absolute also has two kinds of illness. When you manage to reach the absolute but can't forget it because of religious attachment, your subjective view is still there, and you keep a bias toward the absolute; this is one. Even if you pass beyond the absolute it won't do to let go—on close examination, what breath is there? This too is an illness.”These illnesses are all from living on object experiences, without ever cutting through, passing beyond, or turning around and breathing out. Here, if you conceive different thoughts, they become demons and create monsters.

Xuansha said, “Bodhisattvas learning insight must have great potential and great wisdom before they can do so. If you have wisdom, you can get free right now.”

One with great potential understands a thousand-fold on one hearing, attaining great mastery. Talk about “getting” free is already an expedient expression. Why? There's never been any bondage.

Xuansha said, “If your faculties and potential are slow and dull, you should work diligently day and night, forgetting fatigue, going without sleep, missing meals, as if you were in mourning for your parents. If you are this intense all your life, and also get the support of others, with serious research into reality it will be easy to manage. But who can bear to take up this study nowadays?”

Everyone on earth can bear to take it up, unless you are arrogant and have no faith; then even if Shakyamuni Buddha shook the earth with a flash of light, what would that do for you?

Xuansha said, “Don't just memorize sayings, for that is like reciting spells. If you go on blabbering, and are caught and questioned by others, you'll have nowhere to go. Then they'll get mad, saying you haven't answered them. Hearing things like this is painful. Do you know?”

Memorizing sayings is called mixed poison entering the mind, blocking accurate knowledge and perception. Worldly scholars memorize writings a lot, so they cannot adapt fluidly; how then could study of transcendental truth admit of imbibing other people's slobber?

Xuansha said, “There is a kind of monk who sits in the chair of authority and is called a teacher, but when questioned wriggles and gestures, makes eyes, sticks out his tongue, or stares.”

Types like this are completely bedeviled, completely sick. At the end of their lives they will not be able to escape a tumultuous departure.

Xuansha said, “There is another type who talk about the luminous, aware intelligence of the tableau of awareness, the seer and hearer, governor of the physical body. Those who teach like this cheat people tremendously. Do you know? I now ask you—if you take luminous awareness to be your true reality, why isn't it luminously aware when you're fast asleep? If it's not so when you're asleep, why then is it sometimes luminous? Do you understand? This is called taking a thief to be your son. This is the root of birth and death, energy on which imagination focuses.”

This refers to those who play with the spirit. Since they can't be in control when they're fast asleep, how are they going to settle accounts when death comes at the end of life? If they go on acting arbitrarily all their lives, not only will they beguile and cheat others, they will all just beguile and cheat themselves.

Xuansha said, “If you want to produce the governor of the body, just get to know your esoteric adamantine being. The ancients told you that absolute reality is universal, permeating the universe.”

The esoteric adamantine being is absolute reality, universal, permeating the universe. I tell you clearly, you have to merge into it with your whole body in order to realize it.

Xuansha said, “The Way of Buddha is vast, with no stages. The door of liberation is no door, the idea of a wayfarer is no idea. As it is not within past, present, and future, one cannot rise or sink. Fabrication is contrary to reality, which is not something created.”

If you understand the meaning of this, you become a Buddha on the spot, without expending any effort to practice. Indeed, the word “become” is already superfluous.

Xuansha said, “If you're active, you produce the basis of birth and death; if you're still, you get intoxicated by oblivion. When action and stillness both disappear, you fall into nihilism. When action and stillness are both included, you presume upon Buddha-nature.”

Many practitioners dislike activity and take to stillness. After being still for a long time, they crave activity again. You must wake up and break through habituations to activity or stillness—only then are you applying your mind like a wayfarer.

Xuansha said, “You should relate to objects and circumstances as if you were a dead tree or cold ashes, while acting responsively in accord with the time, not overlooking what's appropriate. When a mirror reflects a multitude of images, that doesn't disturb its shininess; when birds fly through the air, that doesn't blur the color of the sky.”

Being like a dead tree or cold ashes means unminding. Not overlooking what's appropriate means dealing with people. How can you talk about this on the same day as those who annihilate their minds and obliterate their intelligence! As for ‘not disturbing the shininess and not blurring the color,' ‘that's up to them—what's it to do with me?'

Xuansha said, “Thus you cast no shadow in any direction, you leave no tracks in any world; you are not stuck in the mechanism of going and coming, and do not dwell on the sense of being in between. If any of this remains incomplete, you become subject to the king of demons. Before the expression and after the expression are difficult points for students; therefore when one expression fits the sky, birth and death end forever in eighty thousand homes.”

In this saying, what is important is “one expression fits the sky” and “eighty thousand homes.” There is no gap in the universe, no shadow, no trace; this can be called shining with light, bubbling with life. Buddhas, Chan masters, and ordinary people have nowhere to place it. As for “birth and death,” who says so?

Xuansha said, “Even if your state is like the reflection of the moon in an autumn pond, not scattering in the ripples, or like the sound of a bell on a quiet night, ringing when stuck without fail, this is still something on the shore of birth and death.”

People who practice sitting meditation rarely attain such a state. Even if they do, it's still something on the shore of birth and death. You have to find your own way to life.

Xuansha said, “The practice of wayfarers is like fire melting ice; it never turns back into ice. Once the arrow has left the bowstring, it has no power to return. That is why wayfarers cannot be held captive and won't turn their heads when called. Even the ancient sages didn't place them; even now they are not situated anywhere.”

The mind of wayfarers should be like this. Break this segment down finely, and in the future you'll naturally save energy. Nothing at all can be added. If you try to focus your conscious mind, that is what is called unreality of the causal basis bringing on twists and turn as a result.

Xuansha said, “People today don't understand the principle herein. They arbitrarily get involved in things, being affected here and there, bound up in this and that. Even if you understand, sense objects are mixed up, names and descriptions are not true.”

“Being affected here and there, bound up in this and that” is just a matter of the examining mind not being intense, so the root of life is not cut off; you are unwilling to die. Genuine students are as if passing through a village where the water is poisoned—don't touch a drop. Only then can you attain a breakthrough.

Xuansha said, “So then they try to still their minds, control their thoughts, and resolve things into emptiness, closing their eyes. The moment a thought arises, they chase it down and root it out; as soon as subtle ideas arise, they immediately suppress them. Those with a view and interpretation like this are nihilistic zombies. Dim and unclear, unawares and unknowing, they cover their ears to steal a bell, only fooling themselves.”

The sickness is in not eliciting the sense of wondering, not looking into cases, not being willing to enter into the principle with the whole body. If you just suppress the conscious mind, even if you are clear and calm, after all the root of life isn't severed, so you are not actually concentrating.

Xuansha said, “Don't remain forever attached to the snare of attraction of birth and death; you'll go on being caught up in good and bad actions and have no independence. Even if you manage to refine body and mind to be like empty space, even if you reach a state of unwavering clarity, you have not gone beyond the cluster of consciousness. The ancients referred to this as like a swift current where the water flows quickly but without realizing it you misperceive it as still.”

If the cognizing mind is not interrupted, even if you refine body and mind to be like space, ultimately you'll be drawn off by bad behavior. The state of unwavering clarity is the cluster of consciousness itself—how can you escape birth and death that way? Speaking in general terms, if you don't find out the great principle, everything is false.

Xuansha said, “If you practice this way, you can't get out of repetitious routines—as before, you continue to be subject to repetitious routines. That is why it is said that all activities are impermanent. Even though the results of the practices of the Three Vehicles are awesome, if you have no enlightened perception they are still not ultimate.”

Summing up the several excerpts of sayings preceding, none of them are ultimate. Even if practitioners of the Three Vehicles carry out the six perfections and ten thousand practices, they are all impermanent, and have no bearing on the noumenal ground of reality.

Jingshan said, “Nowadays there's a kind of deviant whose own eyes are not clear, just teaching people deathlike cessation. If you try to achieve cessation like this, you'll never succeed even after a thousand Buddhas have appeared in the world. You'll just make your mind more confused and uncomfortable.”

If you won't induce the sense of wonder, then the root of life won't be severed. If the root of life isn't severed, you cannot attain cessation. This “cessation” is the root of birth and death; it will never be done.

Jingshan said, “There's another type of person who teaches people to keep concentrated whatever the circumstances, forgetting feelings and silently being aware. If you try to keep up this awareness and maintain this concentration, it will add to your misery, with never an end.”

Since there is a subjective concentrating mind and an object of awareness, subject and object confront each other—what is this if not illusion? If you study with a deluded mind, then you don't have independence in your own mind. You must simply cut off dualism so that subject and object do not stand; then what was blocking your chest will be like the bottom falling out of a bucket.

Jingshan said, “There is also a type of person who teaches others not to concentrate on this matter, but just to cease and desist so that feelings and thoughts don't arise. When they get to this point, they are either blank and unknowing or alert and lucid. This is even more poisonous, blinding people's eyes. This is not a trivial matter.”

Even if you attain alert lucidity, this is in contrast to a state of quiescence; it is not investigation. Investigation is only to discover the great matter—otherwise, what is it but poison?

Jingshan said, “It's not a question of whether you've studied for a long time and are experienced. If you want to attain real peace, you still haven't broken through the mind of birth and death—work so that the mind of birth and death breaks up, and you'll naturally be at peace.”

When the sense of wonder is aroused, the mind of birth and death congeals in one place, so when the sense of wondering is broken through, the mind of birth and death is broken through. In this breakthrough, no sign of movement can be found at all.