The

Tea House

Forrás:

www.teahyakka.com

Teakult,

a Terebess Online különlapja

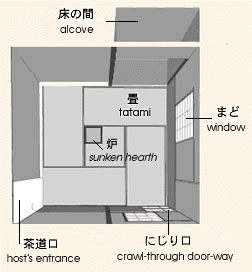

A chashitsu is a building or a room in which the tea ceremony is performed. The purpose of a chaji, or full tea ceremony, is to allow the host an opportunity to express the utmost hospitality to his or her guests. Together, the chashitsu, roji (tea garden), and mizuya (preparation room) should provide the optimum physical and spiritual setting for expressing this hospitality.

To understand the concepts behind chashitsu design, it is essential to be familiar with the flow of action in a chaji. A chaji is like a play consisting of two acts and an intermission. During this play, the host and guests perform a highly ritualized series of actions, carrying on a nearly wordless dialogue of symbolism and feeling.

In the shoza, or first "act," the guests enter the chashitsu from the roji, and once inside, are served a light meal (kaiseki). Following the meal, the host prepares the charcoal for the first time (shozumi). After shozumi, the guests retire to the garden for a short break, "the intermission," and wait for the host to call them back into the chashitsu.

The second "act" of a chaji is called the goza. First the host prepares koicha (thick tea) for the guests. He then prepares the charcoal a second time (gozumi) and makes usucha (thin tea). When all of this is finished, the host and guests silently and respectfully acknowledge each other one last time, and the guests take their leave.

The design of the chashitsu, roji, and mizuya can have a profound effect upon the flow of action in a chaji. Designers strive for both functionality and aesthetics, and despite a highly complex set of design rules, a nearly infinite number of styles is possible.

We start introducing the main elements that make a chasitsu.

Elizabeth

Hurley

Mado, window

Chashitsu windows are made with shoji and function as a decorative element and source of light and air. Size, placement, design and number of windows are crucial in chashitsu design. Windows can be on the host side and/or the guests side and each window has its own characteristics and functions. A mistake in design or of a position of a window may end up confusing users. Names of windows vary depending on their position, shape, or the way they open.

Furosaki mado

|

|

| kake shoji | kadohiki do |

Furosaki mado is a host side window in front of the furo (brazier). As the name explains itself, it is a window placed on the wall which faces the host when preparing tea. Furosaki mado is small, around 55 cm high, its shoji screen is 42.5 cm wide and it is placed around 21 cm above the floor.

It is often used in a koma-seki where the tight feeling between the host and the wall can be soften with the light coming through the shoji paper.

The shoji screen may slide like kadohiki do or be hooked like kake shoji. Usually, the sliding type doesn't open completely and the hooked shoji would not be removed because the idea of furosaki mado is to be designed primarily as a decorative element and a source of light.

Shikishi mado

|

Shikishi mado consists of two windows of which shoji screens resemble two shikishi or square pieces of paper, and are placed one on top of the other. They are often used in daime seki as host side windows. They are placed on the side wall close to the host in the temaeza (host's preparation area). The top window is horizontal and its outside design is generally renji mado. The bottom window is, on the other hand, vertical and its outside design is generally shitaji mado. But they may have two shitaji mado or shitaji mado on the top and renji mado on the bottom depending on the design and necessities.

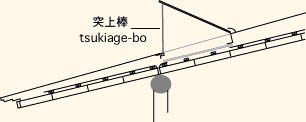

Tsukiage

mado

|

|

| inside view | section |

Tsukiage mado is a skylight window on a ceiling that can be opened by a stick called tsukiage-bo that can be pushed up from the inside. Usually, it is placed either on an inclined ceiling closer to the nijiriguchi (crawling entrance) or on the ceiling above the host side. It is not placed on a horizontal ceiling. There are four different sizes of tsukiage-bo in order to open a window of different heights. The two long tsukiage-bo are square sticks made of cedar, 79 cm and 57.5 cm long, and have a special metal hook shaped like a bird's head on its end. The other two, short ones, are made of bamboo, 30 cm and 14 cm long and 1.8 cm diameter.

|

|

| outside view | inside view |

Shitaji mado is a window in which the plaster wall's inner structure is shown. Today the inner structure is custom made and is added on to the window's opening but it is still possible to find some shita-ji mado that reveal the real wall's inner structure in some old chashitsu.

|

|

| renji mado outside view | |

Renji mado, or windows with lattice, have been used since early times. Some renji mado can be found in Asuka Period temples. Generally, any lattice window or door is called renji. In chashitsu architecture, however, only if the lattice is made of bamboo it is named renji and windows with lattice made by all other trees are named koushi mado. The space between the bamboo pieces, 10.5 cm to 12 cm, in a chashitsu renji mado are slightly wider than what is used in other architecture.

Tatami and Ro

Tatami size

Tatami has three basic sizes:

The maru-tatami(left) is a full sized tatami and han-jyo(center) is a half of maru-tatami.

The daime-tatami(right) has its length determined by subtracting the daisu (original type of utensil stand) and byobu (folding screen) depth from a full tatami size. If necessary, the daime-tatami size can vary slightly, depending on the tea room layout.

Observation: tatami size differs slightly from region to region in Japan. For example, Tokyo size is smaller than Kyoto size tatami (191 cm).

Hiroma, Koma and Yojyohan

The chashitsu can be classified depending on its size as hiroma (large room), yojyohan (four and half tatami-room), and koma (small room).

The four and half tatami room is a standard size room and can be considerated either a large room or a small room depending on how it is used for a chaji, formal tea gathering, or chakai, tea gathering.

Any rooms bigger than four and half tatami are considered large rooms and if smaller than four and half are considered small rooms, as shown below about the ro season tatami layout.

Furo and Ro Season

There are two seasons in the Chanoyu and the layout of tatami of the chashitsu (tea room) changes according to the seasons.

From November to April is the ro (sunken hearth) season when the hearth is set up in the chashitsu. >From May to October, the ro is closed and the furo, brazier, season starts.

Following are displayed the ro (left) and furo (right) season tatami layouts and the respective tatami's names.

|

|

| Ro | Furo |

- kinin

tatami and kyaku tatami are where guests seat.

- dougu tatami is where the utensils are displayed.

- fumikomi tatami is the one to step into from the host's entrance or

sadoguchi.

- ro tatami is where the ro is placed.

- kayoi tatami is the tatami between the fumikomi and kyaku tatami.

Ro

The ro or sunken hearth consists in the rodan, hearth itself, and the robuchi, hearth frame.

The hearth frame is a tea utensil and can be found in various styles.

A "proper" rodan is made of plaster that should be remade every year by a nurishi or a craftsman. There are also rodan made of steel, copper, ceramic and stone.

Inside the rodan, ash is poured in, gotoku or trivet, positioned and the kama or kettle, is set up.

Tokonoma, alcove

A tea room's formal tokonoma called hondoko should face south, get light from its right side and be built with the elements in the figure below.

-Toko-bashira,

alcove post

-Toko-gamachi, alcove frame (lower)

-Otoshi-gake, alcove frame (upper)

-the floor should be covered with tatami.

If one or more of those elements are missing the alcove is called ryakushiki-toko, informal style alcove, as shown below.

-Kabe-doko,

wall-alcove, misses all the elements needed for a hondoko including the tatami

floor. A part of a wall is set up to hang a scroll. Also the wall can have the

koshibari paper mounted on it.

-Oribe-doko, Oribe alcove (kabe-doko), is named after the wood board

called oribe-ita that is set on kabe-doko's upper part. The oribe-ita

is often used to protect scrolls.

-Oki-doko, placed alcove. When a movable wood board or stand is placed

in front of a kabe-doko.

-Tsuri-doko, suspended alcove. It is a kabe-doko with otoshi-gake.

On the other hand if the alcove has all the hondoko's elements but is altered in size or form is called henkei-doko, or modified alcove.

-Fumikomi-doko,

'step in' alcove. The tokonoma's floor level is the same of the room's tatami

level. There is a clear difference between both of them.

-Kekomi-doko. The tokonoma floor has a wooden board that comes out as

a stair step.

-Muro-doko,

a tokonoma plastered all over including the ceiling.

-Fukuro-doko, a tokonoma with a small wall,sode-kabe, built in

one side creating an extra inner space.

-Hora-doko, 'cave' alcove. A fukuro-doko without the frame post and otoshi-gake.

Plaster is used in place of the wooden frame.

-Ganwari-doko, a hora-doko with sode-kabe, side wall, on both sides.

Tokonoma can

be also classified by its width:

-masu-doko, hanjyo tatami size

-daime-doko, daime tatami size

-ikken-doko, maru tatami size

-nana shaku-doko, seven shaku size, tokonoma width between 212-227cm

(1 shaku is about 30.3cm)

-hasshaku-doko, eight shaku size, tokonoma width= 272 cm

-kyuushaku-doko, nine shaku size, tokonma width=302 cm