Terebess

Asia Online (TAO)

Home

Zen Index

.

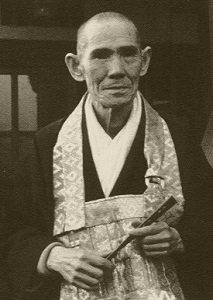

安谷 (白雲) 量衡 Yasutani (Hakuun) Ryōkō (1885-1973)

Paul David Jaffe

YASUTANI HAKUUN

ROSHI

A BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

http://www.sacred-texts.com/bud/zen/yasutani.txt

[This document

constitutes a verbatim fragment (pages 2-13) of the June 1979

MA Thesis in Asian Studies, University of California, Santa Barbara, USA

by Paul David JAFFE entitled:

"The Shobogenzo

Genjokoan by Eihei Dogen, and Penetrating Inquiries into the

Shobogenzo Genjokoan, a commentary by Yasutani Hakuun"

All copyrights to this document (C) 1979 belong to Paul David Jaffe.

This electronic

material by the Coombspapers SSRDB is intended to draw attention

to the existence of P.Jaffe's largely unknown pioneering work and to facilitate

it's eventual printing. It also hopes to aid scholarship concerning the history

of Zen Buddhism in the West.]

[...]

Yasutani Hakuun

Roshi (1885-1973) was a fiery and controversial figure in

20th century Zen Buddhism. He was highly respected for his deep realization

and compassionate teaching, but was also criticized for his polemical stand

against "one sided" teachings and his severe manner of expressing

himself.

We can see within a few pages of his writings what seems a strange mixture

of harsh criticisms of certain teachers as having degraded the Buddha way

and a sincere gratitude for their efforts in guiding him.

It seems that

both his early life and his training under Harada Sogaku Roshi

(1870-1961) contributed to his synthesis of the practices and insights

emphasized in the Soto and Rinzai sects respectively. He was especially vocal

concerning the point of kensho, seeing one's true nature. He spoke more

openly about it then anyone of his times, going so far as to have a public

acknowledgement of those who had experienced kensho in a post-sesshin [4]

ceremony of bowing in gratitude to the three treasures.[5] He was sometimes

criticized for his overemphasis, but according to Robert Aitken Roshi, a

successor in Yasutani's lineage, "I think that Yasutani Roshi's hope was

that

people could get a start, and with that start they could deepen and clarify

it

through koan study. I think that actually Yasutani Roshi placed less

emphasis on kensho than the people who are criticizing him, because the

people who are criticizing him are regarding kensho as some sort of be-all

and end-all, and he didn't look at it in that way at all." [6]

Yasutani was

so outspoken because he felt that the Soto sect in which he

trained emphasized the intrinsic, or original aspect of enlightenment--that

everything is nothing but Buddha-nature itself--to the exclusion of the

experiential aspect of actually awakening tothis original enlightenment. His

dharma successor, Yamada Koun Roshi, has written, "His main purpose was

to

propagate the indispensable place of kensho, Realization of the Way, in Zen."

[7] On the other hand, he criticized the tendency in the Rinzai sect to become

attached to levels and rankings,- and of absolutizing the efficacy of koans

without adequate regard to the realization of emptiness, to which many of

the koans point.

In 1954, some

ten years after his dharma transmission, and after certain

post-war restrictions were lifted, Yasutani established his organization as

an

independent school of Zen. The group, Sambokyodan (Fellowship of the

Three Treasures), broke with the Soto school in which he was ordained,

asserting a position of direct connection with Dogen and no longer

recognizing the authority of the sect's ecclesiastical leaders. Such an action

had been strongly advocated by his teacher Harada Sogaku. [8]

Yasutani Hakuun

Roshi's early background sheds some interesting light on

his subsequent development. There is a miraculous story about his birth: His

mother had already decided that her next son would be a priest when she was

given a bead off a rosary by a nun who instructed her to swallow it for a safe

childbirth. When he was born his left hand was tightly clasped around that

same bead. By his own reckoning, "your life . . . flows out of time much

earlier than what begins at your own conception. Your life seeks your

parents." [9] "It is as if I jumped right into this situation since

while I was

still in her womb my mother was contemplating my priesthood." [10] When

he studied biology in school this story seemed ridiculous, but later he wrote,

"Now, practicing the Buddha Way more and more, understanding many more

channels of the Buddha Way, I realize that it is not so strange but quite

natural. My mother wanted me to become a priest, and because I was

conceived in that wish and because I too desired the priesthood, the juzu

[rosary bead] expressed that karmic relation. There is, indeed, a powerful

connecting force between events. We may not understand it scientifically,

but spiritually we know it is so." [11] So, in time he came to fully accept

this

story and treat it as a concrete symbol of "his deep Dharma affinity."

[12]

The family he

was born into was quite poor; he was adopted by another

family when he was very young. At the age of five he was sent to a country

temple named Fukuji-in near Numazu city. His head was shaved, and he was

educated by the abbot, Tsuyama Genpo. His training at this time was very

strict and meticulous, but also very loving, and left a deep impression on him

throughout his life. At the age of eleven he moved to a nearby temple,

Daichuji, which like Fukuju-in belonged to the Rinzai sect. After a fight with

an older student, however, he was forced to leave. When later he was placed

in another temple, this time it was one of the Soto sect, Teishinji, and it

was

here that he became a monk of the Soto sect under the priest Yasutani Ryogi,

from whom he took his name. At the age of sixteen he went to study under

Nishiari Bokusan Zenji (1821-1910) at Denshinji in Shimada, Shizuoka

prefecture and served as his attendent. Nishiari was well-known both for

having served as the leader of the Soto sect, and for his Shobogenzo keiteki

(The Opening Way of the Shobogenzo). [13] The Keiteki is a record of his

lectures on twenty-nine chapters of the Shobogenzo and is generally

considered an important and authoritative work. In the preface of the work

here partially translated (Shobogenzo sankyu: Genjokoan) Yasutani says of

this Keiteki:

However, beginning

with Nishirari Zenji's Keiteki, I have examined closely

the commentaries on the Shobogenzo of many modern people, and though it

is rude to say it, they have failed badly in their efforts to grasp its main

points. . . .

It goes without saying that Nishiari Zenji was a priest of great learning and

virtue, but even a green priest like me will not affirm his eye of satori. .

. .

. . . the resulting evil of his theoretical

Zen became a significant source of later events.

. . . So it is my earnest wish, in place of Nishiari Zenji, to correct to some

degree the evil which he left, in order to requite his benevolence, and that

of his disciples, which they have extended over many years.[14]

Further, he

tells us that during this period of his life, when he was sixteen or

seventeen, he had two questions. The first was why neither Nishiari Zenji

nor his disciples gave clear guidance concerning kensho when it was

obvious from the ancient writings that all the patriarchs experienced it. The

second concerned what happens after death. He was unable to receive clear

answers or come to an understanding.

Through his

twenties and thirties Yasutani Roshi continued his training

with several other Buddhist priests. He also furthered his education, going

to

a teacher training school and then beginning a ten year career as an

elementary school teacher and principal. At thirty he married and started

raising a family which was to produce five children.

In 1925, at

the age of forty, he returned to his vocation as a Buddhist priest.

Soon after, he was appointed as a Specially Dispatched Priest for the

Propagation of the Soto sect, travelling around giving lectures. "However,"

he wrote in 1952 in the epilogue to Shushogi Sanka (Song-in Praise of the

Shushogi), [15] "I was altogether a blind fellow, and my mind was not yet

at

rest. I was at a peak of mental anguish. When I felt I could not endure

deceiving myself and others by untrue teaching and irresponsible sermons

any longer, my karma opened up and I was able to meet my master Daiun

Shitsu, Harada Sogaku Roshi. The light of a lantern was brought to the dark

night, to my profound joy." [16]

Harada Roshi

was a Soto priest, educated at the Soto sect's Komazawa

University. His sincere searching brought him to study with Toyota Dokutan

Roshi (1841-1919), abbot of Nanzenji, the head temple of the branch of Rinzai

Zen known by the same name. After completing koan study and becoming a

dharma successor, Harada became abbot of Hosshinji, a Soto temple,

transforming it into a rigorous and lively training center. [17]

Yasutani Roshi

sat his first sesshin with Harada Roshi in 1925 and two years

later at the age of forty-two was recognized as having attained kensho. Some

ten years later he finished his koan study and then, at the age of fifty-eight,

received dharma transmission from Harada Roshi on April 8, 1943. [18]

Yasutani Roshi's career as a Zen teacher was devoted and single-minded. He

was head of a training hall for monks for a short while, but gave it up and

applied his efforts primarily toward the training of lay practitioners. His

years leading a family life and working as an educator no doubt both

influenced him in this direction and prepared him for the task. During the

next thirty years he held over three hundred sesshins, led numerous regular

zazen meetings, and lectured widely. In addition, he left almost one hundred

volumes of writings. [19]

Already in his

late seventies, Yasutani Roshi first travelled to the United

States in 1962, at the instigation of some of his American students. He held

sesshins in over half a dozen cities, and due to an enthusiastic response made

six more visits continuing through 1969. He has exerted a profound

influence on the budding American Zen tradition through direct contact

with many students and through his relationships with several of the

leading Zen teachers in America today. Yasutani has also become widely

known and indirectly influenced many people through the book Three

Pillars of Zen, compiled by Phillip Kapleau and published in 1965. It contains

a short biographical section on Yasutani Roshi and also his "Introductory

Lectures on Zen Training," "Commentary on the Koan Mu," and the

somewhat

unorthodox printing of his dokusan interviews with ten western

students.[20]

Kapleau was

the first westerner to study with Yasutani Roshi. This was in

1956 after Kapleau had studied for three years at Hosshinji under the

guidance of Harada Roshi. After some twenty sesshin with Yasutani, the

Roshi confirmed Kapleau's kensho experience which is one of the cases set

down in Three Pillars. It was Kapleau who first suggested to Yasutani Roshi

that he visit America. In 1966 Kapleau founded the Rochester Zen Center,

which now has several hundred students in Rochester as well as several

affiliated sitting groups in Canada, the United States and Europe. [21]

Another of Yasutani's

early American students was Robert Aitken, who first

sat with him in 1957. Aitken's steadily deepening interest in and practice of

Zen started when he was picked up off Guam by the Japanese during the

Second World War, and found himself in the same internment camp as R. H.

Blyth, the author of Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics. Aitken,

along with Kapleau, was instrumental in arranging Yasutani's original

journey to the U.S. and on that and subsequent trips through 1969 hosted him

for sesshins at Koko-an, his small Zen center in Honolulu, and in 1969 at the

newly established Maui Zendo. Aitken says of Yasutani, his only teacher

during this period, "He devoted himself fully to us. We felt from him the

importance of intensive study, of dedication and also something of

lightness." Aitken further characterizes- him as "like a feather but

still full

of passion," and having "a ready laugh."[22] Aitken studied further

with

Yasutani Roshi and his successor Yamada Koun and received transmission

from Yamada in 1974, making him the first westerner to become a dharma

successor in the Yasutani/Harada lineage. Aitken Roshi's Diamond Sangha

now includes two practice centers in Hawaii and about 100 students, and he

periodically conducts sesshin in Tacoma, Washington; Nevada City,

California; and Australia.

Eido Tai Shinamo

(1932- ) first met Yasutani Roshi in 1962 when he was a

young monk who had spent about two years in Hawaii. [23] His own teacher

Nakagawa Soen Roshi took him to meet Yasutani one day. Soen Roshi was

planning a trip to the U.S. and invited Yasutani to join him, which he agreed

to do. Then he invited Eido to go along also. Shortly before the trip Soen

Roshi cancelled his plans due to the illness of his mother. Eido was left to

accompany Yasutani as his attendant and translator. The following year Eido

again accompanied Yasutani to America and they continued on around the

world together. On Soen's request Yasutani guided Eido in his koan study.

Later Eido wrote, "During his seven times teaching pilgrimage, from the

very beginning to the end, I was fortunate enough to serve him as an

attendant monk and as an interpreter. I received great teaching from him in

many ways."[24] "He was a brilliant master."[25] Eido Roshi,

who received

dharma transmission from Soen Roshi in 1972, is now the leader of the New

York Zendo in Manhattan and the Dai Bosatsu Zendo in the Catskill mountains

of New York state, and has affiliate groups in Washington D.C., Boston and

Philadelphia. Altogether some 300 students are guided by Eido Roshi.

Maezumi Taizan

Roshi, who came to America in 1956, has become a dharma

successor of Yasutani. Originally having come to the United States to serve

in

the Soto Zen Mission in Los Angeles, it was here in 1962 that Maezumi first

met Yasutani Roshi. Maezumi, a young priest at the time, had, perhaps, a

particular affinity with Yasutani. In addition to having been born into,

raised, educated and trained in the Sotc tradition, he had also done koan study

with Osaka Koryu Roshi, a lay master in the Rinzai school. When Yasutani

Roshi came to Los Angeles, Maezumi started to do koan study with him.

Between Yasutani's several trips to America and Maezumi's trips to Japan to

continue his study, the two developed their relationship further. On

December 7, 1970, Maezumi received the seal of dharma succession. Since he

is also a dharma successor of Kuroda Hakujun Roshi in the Soto tradition, and

Osaka Koryu Roshi in the Rinzai tradition, Maezumi Roshi holds a unique

position.

At the Zen Center

of Los Angeles which was founded by Maezumi in 1966,

Yasutani Roshi's approach of integrating the emphasis of the Soto and Rinzai

schools seems to be taking root in America. The fact that this community of

about 100 people affords the possibility of a family-based practice also

reflects, in part, Yasutani Roshi's emphasis on lay practice. The community

includes several families with children; there is even a cooperatiye child

care program. The Zen Center of Los Angeles has over 200 members who

practice under the guidance of Maezumi Roshi.

This background

of Yasutani Roshi's role in Zen Buddhism shows him to be

an important figure in transplanting it to a new continent.

[....]

NOTES

[... Notes 1-3 have been omitted from this document... - the Coombspapers]

4 Sesshin ***ideographs*** is a fixed period of intensive practice of

zazen. In Japan five days or a week is the most common length of time.

5 Three treasures

(Skt.: triratna; J.: sambo): Buddha, dharma and sangha.

In Zen the three terms are also taken respectively as symbols of

oneness, multiplicity and the harmony between the two.

6 Rick Fields, Buddhist America, unpublished manuscript in progress.

7 Koun Yamada,

"The Stature of Yasutani Hakuun Roshi," in Eastern

Buddhist, n.s., 7.2 (1974): 119.

8 Ibid., 120.

9 Hakuun Yasutani

"My Childhood," trans. by Taizan Maezumi from Zen

and Life (Fukuoka: Shukosha, 1969). in ZCLA Journal, 3.3 & 4 (1973): 34.

10 Ibid., 32.

11 Ibid., 32-34.

12 Yamada, "Stature," 118.

13 Nishiari Bokusan

***ideographs***, Shobogenzo keiteki

***ideographs*** ed. by Kurebayashi Kodo ***ideographs***, 3 vols.

(Tokyo: Daihorinkaku, 1965).

14 Yamada, "Stature," 116-117.

15 Shushogi ***ideographs***

is an anthology of selections from

Dogen's writings compiled in 1890 for use by followers of the Sot8

school.

16 Yamada, "Stature," 109.

17 Hakuyu Taizan

Maezumi and Bernard Tetsugen Glassman, The Hazy

Moon of Enlightenment (Los Angeles: Center Publications, 1978), p.

194.

18 Japanese Buddhists celebrate the Buddha's birthday on April 8.

19 Tetsugyu Ban, "Dharma Words," in ZCLA Journal, 3.3 & 4 (1973): 26.

20 Dokusan ***ideographs***

is a formal, private interview between the

master and the student, usually conducted during periods of zazen.

21 Figures for

students in this section are necessarily rough. I have

gathered information primarily from conversation with members of

these various centers.

22 Personal interview, May 8, 1979.

23 The relationship

between Eido and Yasutani is described in Nyogen

Senzaki, Soen Nakagawa and Eido Shimano, Namu Dai Bosa (New York:

Theatre Arts Books, 1976), pp. 182-188.

24 Mui Shitsu Eido,"White Cloud," in ZCLA Journal, 3.3 & 4 (1973): 50.

25 Ibid., 51.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Harada-Yasutani

School of Zen Buddhism

This document is a part of the Zen Buddhism section of the Buddhist Studies

WWW Virtual Library

Edited by Dr T.Matthew Ciolek

http://www.ciolek.com/WWWVLPages/ZenPages/HaradaYasutani.html

----------------------------------------------------------------------

YASUTANI

Haku'un Roshi

http://homepage3.nifty.com/sanbo-zen/histry_e.html

The Sanbô Kyôdan is a Zen-Buddhist Religious Foundation (shukyô-hôjin)

started by YASUTANI Haku'un Roshi on 8 January 1954.

YASUTANI Roshi, who was born on 5 January 1885 in Shimizu City, Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan, formally became a Soto Buddhist monk when he was 13 years old. In 1925 he met HARADA Sogaku Roshi (1871-1961), and eventually became one of his Dharma successors. YASUTANI Roshi deplored how the Soto monks of the time were preoccupied with superficially carrying out Buddhist ceremonies and neglected the vital practice of realizing one's true self. So he left the Soto school and founded an independent religious foundation, the Sanbô Kyôdan, in order to re-vitalize authentic Zen among those earnest seekers of the Way, who, at that time, happened to be mostly lay people. "Sanbô," literally "three treasures," signifies the three most basic principles of Buddhism: Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. "Kyôdan," on the other hand, means "religious organization." In this name, therefore, one can perceive YASUTANI Roshi's aspiration as well as his determination to create a religious community that purely devotes itself to maintaining the true Buddhist Way.

The genesis of the foundation reveals already that the basic character of the organization is that of the Soto line. But, following the tradition stemming from HARADA Sogaku Roshi, the Sanbô Kyôdan integrated the Rinzai method of koan study as well in its Zen training in order to bring its students effectively to the realization of their true self.

YASUTANI Roshi thus instructed a countless number of practitioners both in Japan and, from 1962 on, in Europe and the United States. In 1970 he resigned from the abbotship of the Sanbô Kyôdan and had YAMADA Kôun Roshi take the leadership of the organization. YASUTANI Roshi passed away on 28 March 1973.

Sharf, Robert H. Sanbôkyôdan Zen

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Fukan-Zazen-Gi

Aus: Karlfried Graf Dürckheim

Wunderbare Katze und andere Zen-Texte

Copyright der deutschen Ausgabe © 1996 Herder Verlag Freiburg

Ein Text des Zen-Meisters Dogen, erläutert von Meister Hakuun Yasutani, übersetzt aus dem Japanischen von Fumio Hashimoto.

----------------------------------------------------------------------