Terebess

Asia

Online

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Chinese Furniture: Materials

Indigenous Hardwoods and Softwoods

Boxwood (Huangyang)

Buxus L.Burl (Yingmu, Huamu)

Camphor (Xiangzhang)

Cinnamomum camphoraCypress (Baimu, Bomu)

Cupressus L.Huaimu (Chinese Locust)

Robinia Pseudoacacia L.Jumu (Southern Elm, Zelkova)

Zelkova SchneiderianaNanmu

Phoebe neesOak (Zuomu, Gaolimu)

Cyclobalanopsis (Qingfeng) and Quercus L. (Mali)Walnut (Hetao)

JuglansYumu (Northern Elm)

Ulmus L.Zhazhen

Tropical Hardwoods

Hongmu

Huanghuali

Jichimu

Tieli wood

Ebony (Wumu)

Miscellaneous Materials

Decorative Stone

Paktong

Woven Cane

Boxwood (Huangyang)

Buxus L.

Boxwood is a small tree and shrub. Due to the limited

size of the material, it is rarely used for full-sized pieces of furniture, but

more often for small, carved objects or as decorative inlay. Boxwood is very durable

and dense (.83-.93 g/cm3), and its fine even texture makes it especially suitable

for carving.

Boxwood is a small tree and shrub. Due to the limited

size of the material, it is rarely used for full-sized pieces of furniture, but

more often for small, carved objects or as decorative inlay. Boxwood is very durable

and dense (.83-.93 g/cm3), and its fine even texture makes it especially suitable

for carving.

Numerous varieties, which all produce material of similar

characteristics, are widely distributed throughout China; noted timber varieties

are also harvested in Hubei, Jiangxi, and Sichuan. The tree grows very slowly,

with some varieties reaching only 10-15 cm diameter after 100 years; forests of

Laoshan in Shandong produce boxwood trees with diameters reaching 30 cm.

The sapwood and heartwood of boxwood are indistinguishable, and their freshly

cut pale-yellow color turns to a warm brownish-yellow tone after exposure. The

grain is usually very straight, but can also be irregular. The timber is difficult

to dry and especially prone to splitting. Freshly worked boxwood has an earthy

fragrance. Because of its extremely small vessel cells, the texture is exceptionally

smooth and fine, and the surface polishes to a silky luster.

Burl (Yingmu, Huamu)

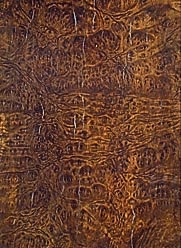

Burls are abnormal projections that bulge out from

or encircle the trunks or branches of trees. What causes them remains unknown

and their tumor-like growth does not appear to adversely affect the tree's health.

Various theories suggest that they result from falling trees, fire or frost damage,

invading fungus or bacteria, or even woodpeckers. Certain species, such as camphor,

elm, nanmu, cypress, and willow also seem to be more susceptible to burl growths.

Burls are abnormal projections that bulge out from

or encircle the trunks or branches of trees. What causes them remains unknown

and their tumor-like growth does not appear to adversely affect the tree's health.

Various theories suggest that they result from falling trees, fire or frost damage,

invading fungus or bacteria, or even woodpeckers. Certain species, such as camphor,

elm, nanmu, cypress, and willow also seem to be more susceptible to burl growths.

The wood tissue of a burl is extremely disoriented and is comprised of many

small bud formations that often appear as clusters of round curls. It is often

difficult to distinguish one burl species from another. However, similar coloring,

texture, and grain patterns of the parent tree can often be detected.

Nanmu burl is often described

as having a "grape seed pattern," which describes the tiny seed-like bud formations

within it. Such burl may also come from the roots of massive nanmu trees.

Wood from the junction of the trunk and roots is full of interesting and distorted

figure caused by the changes in direction of the wood fibers as they branch out

as roots, and by the effects of compression from bearing the weight of the tree.

Nanmu burl is often described

as having a "grape seed pattern," which describes the tiny seed-like bud formations

within it. Such burl may also come from the roots of massive nanmu trees.

Wood from the junction of the trunk and roots is full of interesting and distorted

figure caused by the changes in direction of the wood fibers as they branch out

as roots, and by the effects of compression from bearing the weight of the tree.

Burl-like figure also frequently develops in several varieties of birch (huamu

(Betula)) that grow throughout China. The heartwood is generally light yellow

and sometimes figured with rust-colored 'bird's-eye' or striped patterns. In Chinese,

the term huamu is used interchangeably for birch and birch with burl-like figure,

as well as for burls in general.

Camphor (Xiangzhang)

Cinnamomum

camphora

Because of its resistance to insects as well as its

attractive grain patterns, camphor wood has long been used for making wardrobes

and storage chests. Camphor is a large evergreen tree of the laurel family. It

frequently grows to huge proportions approaching 50 meters in height with trunks

reaching 5 meters in diameter. It is widely distributed south of the Yangzi River

including Hainan Island, with the largest concentrations found in Taiwan, followed

by Jiangxi and Fujian.

Because of its resistance to insects as well as its

attractive grain patterns, camphor wood has long been used for making wardrobes

and storage chests. Camphor is a large evergreen tree of the laurel family. It

frequently grows to huge proportions approaching 50 meters in height with trunks

reaching 5 meters in diameter. It is widely distributed south of the Yangzi River

including Hainan Island, with the largest concentrations found in Taiwan, followed

by Jiangxi and Fujian.

The pale sapwood of camphor is clearly distinguished

from the heartwood, whose reddish-brown color is typically figured with darker

reddish striations. The fragrance of camphor is intense after freshly cut, and

its strong scent does not diminish with time. The interlocked grain pattern of

camphor imparts a light and dark striped figure patterned with its open pores

appearing as slanted parallel lines in the radial surface. It is light to medium

in weight (.42-.54 g/cm3) and soft to medium in hardness. It is relatively stable

but not particularly strong as a timber. The texture is even, and the surface

can be polished to a rich luster.

Yellow Camphor (C. parthenoxylon)

also grows throughout southern China, but does not reach the mammoth proportions

of its relative. Although the material is similarly figured, it is lighter in

color, and less dense; and after cutting, its fragrance dissipates with time.

This material is often substituted for the more highly prized variety.

Cypress (Baimu, Bomu)

Cupressus

L.

Cypress is categorized along

with nanmu in the Song dynasty Yingzao fashi categorizes as a "miscellaneous

soft wood" (za ruanmu). Late Ming connoisseurs noted the use of Sichuan

cypress as a suitable furniture-making material, and Qing dynasty records from

the Yuanmingyuan also indicate that southern cypress was of comparable value to

nanmu.

Cypress is categorized along

with nanmu in the Song dynasty Yingzao fashi categorizes as a "miscellaneous

soft wood" (za ruanmu). Late Ming connoisseurs noted the use of Sichuan

cypress as a suitable furniture-making material, and Qing dynasty records from

the Yuanmingyuan also indicate that southern cypress was of comparable value to

nanmu.

Of several cypress varieties found in modern China, Weeping

Cypress (C. funebris) is the most highly regarded for its timber. It is

heavily concentrated in Sichuan where it reaches heights of thirty meters and

two meters in diameter. Smaller varieties of lesser quality include Bhutan Cypress,

with concentrations in Gansu, Fujian Cypress, distributed throughout southern

China to the Vietnamese border regions, and Himalayan Cypress (Xizang bai).

The heartwood of Weeping Cypress has a grassy yellowish-brown tonality, and

is sometimes slightly streaked with red. With prolonged exposure, the color becomes

deeper; the sapwood has paler tonalities. The material has good luster, is somewhat

waxy or oily to the touch, and has a pungent fragrance. The grain is generally

quite straight and evenly textured. The weight, density (±.58 g/cm3) and hardness

are both medium to high. Drying is relatively slow, and requires attention to

avoid warpage problems. Afterwards, it is highly resistant to rot and insect damage.

The finely textured material is easy to work and polishes to a bright surface.

Huaimu (Chinese Locust)

Robinia Pseudoacacia

L.

Locust initially appears quite similar to northern

elm. In the Northern Song architecture treatise Yingzao fashi, locust and

elm (yu) were categorized "miscellaneous hardwoods" of similar sawing difficulty.

However, locust is appreciably more dense (.79-.81 g/cm3), and the surface is

more coarsely textured.

Locust initially appears quite similar to northern

elm. In the Northern Song architecture treatise Yingzao fashi, locust and

elm (yu) were categorized "miscellaneous hardwoods" of similar sawing difficulty.

However, locust is appreciably more dense (.79-.81 g/cm3), and the surface is

more coarsely textured.

Locust is distributed throughout China, however

the best is considered to come from northern China. Aside from its noted density,

the timber is hard and very strong. The pores in the early wood can be relatively

large; the grain is relatively straight but unevenly textured. It is relatively

easy to dry, with little warpage; however, it tends to develop large cracks. After

drying, the wood is quite stable and naturally resistant to moisture and insect

damage. It is difficult to cut and to surface; however, afterwards, it reveals

a lustrous surface.

Jumu (Southern Elm, Zelkova)

Zelkova

Schneideriana

Southern Elm was a popular furniture-making wood in

the Suzhou region. It is distinguished from its northern counterpart by a more

refined ring porous structure that is apparent in the tangential surface, and

by small medullary rays that are visible as fine reflective flecks across the

radial surface. Southern Elm is also comparatively denser and stronger.

Southern Elm was a popular furniture-making wood in

the Suzhou region. It is distinguished from its northern counterpart by a more

refined ring porous structure that is apparent in the tangential surface, and

by small medullary rays that are visible as fine reflective flecks across the

radial surface. Southern Elm is also comparatively denser and stronger.

Southern Elm is widely distributed throughout China with concentrations found

in Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Anhui provinces as well as Korea and Japan, where it

is commonly known as keyaki. The arbor reaches 30 meters in height and

the trunk, 1.5 meter in diameter.

The sapwood is distinguished from the

slightly darker heartwood, which varies in tonality from yellowish brown to coffee-brown.

Jiangsu craftsmen traditionally divide jumu into three types: yellow ju (huangju),

red ju (hongju), and blood ju (xueju). Factors including the age

of the tree are thought to account for these variations in color as well as ranging

densities (63-.79 g/cm3). Blood ju, with a reddish-brown coffee color as well

as some feathery like figure in the tangential surface, is the most highly prized.

Nanmu

Phoebe nees

Nanmu and nanmu burl

(douban nan) were frequently mentioned as materials par excellence in Ming

literati writings. The former was often used for cabinet construction; the latter,

for decorative cabinet door and table top panels as well as smaller scholar's

objects.

Nanmu and nanmu burl

(douban nan) were frequently mentioned as materials par excellence in Ming

literati writings. The former was often used for cabinet construction; the latter,

for decorative cabinet door and table top panels as well as smaller scholar's

objects.

Nanmu is a large, slow growing tree of the evergreen

laurel family that develops with a long straight trunk ranging from 10-40 meters

in height, and 50 to 100 cm in diameter. While sharing some characteristics with

the coniferous cedar, it bears no botanical relationship. More than thirty varieties

are found south of the Yangzi River with concentrations in the southwest; varieties

are also indigenous to Hainan Island and Vietnam.

Zhennan (True

Nanmu) from Sichuan and Guizhou, zinan (Purple Nanmu) from the southeastern

and south-central regions, and hongmaoshan nan (Hongmao Mountain Nanmu)

from Hainan Island are generally considered to produce the finest timber. These

wood ranges in color from a warm olive-brown color to a reddish-brown color. Other

species of nanmu with a coarse, loosely structured grain and lighter color

are considered inferior.

Because it is highly resistant to decay, nanmu

was frequently used for architectural woodworking and boat-building. The wood

dries well with minimal warping or splitting after which it is dimensionally stable

and of medium density (zhennan ±.61 g/cm3). Nanmu also emits a pungent

fragrance when freshly worked. And because it polishes to a shimmering surface

and has fine smooth texture, it was also prized as furniture-making wood. Shimmering

characteristics also qualify that which is termed 'jinsi' (golden-thread)

nanmu. The burl of nanmu (douban nan) was also commonly featured

in table and cabinet door

Oak (Zuomu, Gaolimu)

Cyclobalanopsis

(Qingfeng) and Quercus L. (Mali)

Although furniture made from oak is somewhat rare,

the material has long been known as an excellent furniture-making wood. The variety

known as gaoli was used in the Yongzheng (1723-1735) Imperial workshops,

and earlier examples have also survived. Botanists have identified one hundred

forty types of oaks widely distributed throughout China. These are divided into

the evergreen Qingfeng group and the Mali group, the latter inclusive of both

deciduous and evergreen varieties. Three species suited for furniture-making are

noted below.

Although furniture made from oak is somewhat rare,

the material has long been known as an excellent furniture-making wood. The variety

known as gaoli was used in the Yongzheng (1723-1735) Imperial workshops,

and earlier examples have also survived. Botanists have identified one hundred

forty types of oaks widely distributed throughout China. These are divided into

the evergreen Qingfeng group and the Mali group, the latter inclusive of both

deciduous and evergreen varieties. Three species suited for furniture-making are

noted below.

The Blue Japanese Oak (C. glauca) is widely distributed

from Japan to India and commonly reaches heights of 20 meters with trunk diameters

of one meter. The sapwood and heartwood are not clearly distinguished and range

from grayish-yellow to grayish-brown with streaks of brown or red. The material

is difficult to dry and not easy to work, however, it is extremely dense (±.90

g/cm3) and hard. Distinctive medullary rays appear in the tangential surface as

short dark lines; in the radial surface, they appear as lustrous flecks woven

through the longitudinal grain. The Sawtooth Oak (Q. acutissima) is also

broadly distributed throughout China. With the exception of its reddish-brown

heartwood, other characteristics are similar to the Blue Japanese Oak.

The somewhat less dense (.67-.75 g/cm3) Mongolian Oak (Q. mongolica) grows

throughout north central and northeastern China, and is found from stretching

westward through Japan , Korea, Mongolia, and Siberia. A similar species of growing

in the Xing'anling region of Mongolia has been related to that commonly termed

gaoli mu---Gaoli being a Chinese reference to ancient Korea.

Walnut (Hetao)

Juglans

Walnut was used for many examples of Qing period furniture

sourced from the Shanxi region, which generally demonstrate refined workmanship;

earlier pieces are extremely rare. Walnut is easily confused with nanmu,

however, the surface of walnut tends to have more of an open-grained texture,

and the color tends more towards golden-brown or reddish-brown when contrasted

with the olive-brown tones of nanmu. Furthermore, their freshly worked

surfaces each emit a distinctive fragrance.

Walnut was used for many examples of Qing period furniture

sourced from the Shanxi region, which generally demonstrate refined workmanship;

earlier pieces are extremely rare. Walnut is easily confused with nanmu,

however, the surface of walnut tends to have more of an open-grained texture,

and the color tends more towards golden-brown or reddish-brown when contrasted

with the olive-brown tones of nanmu. Furthermore, their freshly worked

surfaces each emit a distinctive fragrance.

China has several species

of walnut that produce timber suited for high-quality furniture-making. True Walnut

(J. regia L.) is generally cultivated in the north and northwestern regions,

but also extends into the southwestern provinces. It is a deciduous tree reaching

20 meters in height that produces an edible nut that can be pressed into a high-quality

vegetable oil. The light-colored sapwood is clearly distinguishable from the heartwood,

the latter being reddish-brown too chestnut-brown in color, and sometimes even

purplish, or with darker striated patterning. It dries very slowly, but is quite

stable afterwards. It is of medium density (±.62 g/cm3) and has a relatively fine

texture.

Because True Walnut is generally cultivated for its fruit rather

than timber, Manchurian Walnut (J. mandsharica M.) is often used in its

place. It is distributed throughout the northern to northeastern forests of China.

It is somewhat lower in density (±.53 g/cm3) than True Walnut, and somewhat lighter

in color. Wild Walnut (J. cathayensis) is distributed throughout central-to-eastern

China, with noted concentrations in Yunnan province.

Yumu (Northern Elm)

Ulmus L.

Northern Elm is the most common furniture-making wood

found throughout northern China. It is referred to throughout the catalogue as

Northern Elm to differentiate it from the somewhat similar appearing Zelkova,

which is also commonly called elm, or Southern Elm.

Northern Elm is the most common furniture-making wood

found throughout northern China. It is referred to throughout the catalogue as

Northern Elm to differentiate it from the somewhat similar appearing Zelkova,

which is also commonly called elm, or Southern Elm.

There are over twenty

varieties of elm which are widely distributed tree throughout China, but more

highly concentrated in the northern regions. Northern varieties noted for producing

furniture-making timber include the Japanese Elm (chunyu (U. davidiana var.

japonica)), which reaches 30 meters in height and 1 meter in diameter, and

the somewhat smaller Manchurian Elm (lieye yu (U. laciniata)). These, along

with the more broadly distributed Siberian Elm (bai yu (U. pumila)) all

share similar characteristics.

The sapwood of Northern Elm is yellowish-brown;

the heartwood, a slight chestnut brown. The wood is difficult to dry and easily

develops cracks. The material is of medium density (.59-.64 g/cm3) and hardness,

and with the exception of Siberian elm, has relatively low strength. The material

is somewhat resistant to decay and easy to work. Because the wood is ring porous,

with a wave-like patterning in the growth rings of the late wood, the tangential

surface often reveals a layered, feather-like figure that is popular for furniture-making.

Chinese Elm (lang yu (U. parviflora)) is more concentrated in the

southern tropical regions, but is also found throughout Shaanxi, Shanxi, Hebei.

Its coffee-colored heartwood may also relate to the furniture-making wood popularly

called Purple Elm (ziyu). This timber is also difficult to dry, easy to

warp and split, but considerably denser (±.90 g/cm3) and harder than the other

varieties. It has high structural strength, but the grain patterning is not as

striking as Japanese Elm or Siberian Elm; it is also more difficult to work.

Zhazhen

Commonly termed zhazhen or zhajing,

this furniture-making wood is associated with the mulberry species. Furniture

made from zhazhen wood is commonly found in the Subei region of Jiangsu.

The wood is dark reddish-brown and layered with coffee-colored tissue; it has

a fine grain pattern with medullary rays visible in the radial cut. The material

is of medium density, but has low resistance to decay.

Commonly termed zhazhen or zhajing,

this furniture-making wood is associated with the mulberry species. Furniture

made from zhazhen wood is commonly found in the Subei region of Jiangsu.

The wood is dark reddish-brown and layered with coffee-colored tissue; it has

a fine grain pattern with medullary rays visible in the radial cut. The material

is of medium density, but has low resistance to decay.

Hongmu

No early references to hongmu

have yet been discovered; however, the equivalent southern Chinese term 'suanzhi'

appears during the middle Qing period—its literal meaning, 'sourwood' describes

the pungent odor emitted when it is worked. Most of the dark heavily carved Qing

period furniture is made from hongmu. Also called 'blackwood', it can resemble

zitan but lacks the latters deep lustrous surface and its 'crab-claw markings'.

There is also a light variety which can be difficult to distinguish from huanghuali.

No early references to hongmu

have yet been discovered; however, the equivalent southern Chinese term 'suanzhi'

appears during the middle Qing period—its literal meaning, 'sourwood' describes

the pungent odor emitted when it is worked. Most of the dark heavily carved Qing

period furniture is made from hongmu. Also called 'blackwood', it can resemble

zitan but lacks the latters deep lustrous surface and its 'crab-claw markings'.

There is also a light variety which can be difficult to distinguish from huanghuali.

Huanghuali

The Chinese term huanghuali

literally means "yellow flowering pear" wood. It is a member of the rosewood family

and is botanically classified as Dalbergia odorifera. In premodern times

the wood was know as huali or hualu. The modifier huang (yellowish-brown)

was added in the early twentieth century to describe old huali wood whose

surfaces had mellowed to a yellowish tone due to long exposure to light. The sweet

fragrance of huali distinguishes it from the similar appearing but pungent-odored

hongmu.

The Chinese term huanghuali

literally means "yellow flowering pear" wood. It is a member of the rosewood family

and is botanically classified as Dalbergia odorifera. In premodern times

the wood was know as huali or hualu. The modifier huang (yellowish-brown)

was added in the early twentieth century to describe old huali wood whose

surfaces had mellowed to a yellowish tone due to long exposure to light. The sweet

fragrance of huali distinguishes it from the similar appearing but pungent-odored

hongmu.

The finest huanghuali has a translucent shimmering

surface with abstractly figured patterns that delight the eye--those appearing

like ghost faces were highly prized. The color can range from reddish-brown to

golden-yellow. Historical references point to Hainan Island as the main source

of huali. However, variations in the color, figure, and density suggest

similar species sourced throughout North Vietnam, Guangxi, Indochina and the other

isles of the South China Sea.

The finest huanghuali has a translucent shimmering

surface with abstractly figured patterns that delight the eye--those appearing

like ghost faces were highly prized. The color can range from reddish-brown to

golden-yellow. Historical references point to Hainan Island as the main source

of huali. However, variations in the color, figure, and density suggest

similar species sourced throughout North Vietnam, Guangxi, Indochina and the other

isles of the South China Sea.

Jichimu

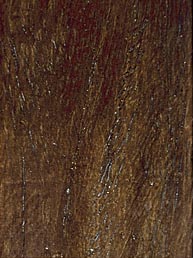

Jichimu, literally translated

as 'chicken-wing wood', describes a wood whose deep brown and gray patterns when

cut tangentially resemble the patterns of bird feathers. The radial cut appears

less dramatically with parallel lines of concentric layered tissue. It is botanically

classified in the Ormosia genus of which as many as twenty-six species

may grow in China. Jichimu is indigenous to Hainan Island, and the relatively

large quantity of jichimu furniture found in Fujian province also corresponds

to a source where seven different species are reportedly found today, and whose

materials are virtually undifferentiated, yet bear varying leaf patterns. Hongdou

(red bean), and xiangsi may also be other names for related species.

Jichimu, literally translated

as 'chicken-wing wood', describes a wood whose deep brown and gray patterns when

cut tangentially resemble the patterns of bird feathers. The radial cut appears

less dramatically with parallel lines of concentric layered tissue. It is botanically

classified in the Ormosia genus of which as many as twenty-six species

may grow in China. Jichimu is indigenous to Hainan Island, and the relatively

large quantity of jichimu furniture found in Fujian province also corresponds

to a source where seven different species are reportedly found today, and whose

materials are virtually undifferentiated, yet bear varying leaf patterns. Hongdou

(red bean), and xiangsi may also be other names for related species.

Tieli wood

Tieli wood is often confused with jichimu,

yet lacks the latter's contrasting colors. Tieli is predominantly grayish

black, and its open grain has a coarse texture. It once grew abundant in Guangdong

where its large timbers were used for bridges and house construction; on Hainan

Island the natives used it for firewood. Nevertheless, in the more northern regions

its was regarded as a rare hardwood and was noted for as a desirable wood for

furniture-making in late Ming texts. Furniture made from tieli often has

a thick quality and is frequently with little or no carved decoration.

Tieli wood is often confused with jichimu,

yet lacks the latter's contrasting colors. Tieli is predominantly grayish

black, and its open grain has a coarse texture. It once grew abundant in Guangdong

where its large timbers were used for bridges and house construction; on Hainan

Island the natives used it for firewood. Nevertheless, in the more northern regions

its was regarded as a rare hardwood and was noted for as a desirable wood for

furniture-making in late Ming texts. Furniture made from tieli often has

a thick quality and is frequently with little or no carved decoration.

Ebony (Wumu)

Wumu, or ebony, is botanically related to the

Ebenacea family. It has a fine closed grain which is very brittle, and

the color can be pure black to black and brown. Because it grows as a small-diameter

tree, it is rarely used as primary material for large pieces of furniture, but

more often shaped into secondary decorative elements or as small precious objects.

Wumu, or ebony, is botanically related to the

Ebenacea family. It has a fine closed grain which is very brittle, and

the color can be pure black to black and brown. Because it grows as a small-diameter

tree, it is rarely used as primary material for large pieces of furniture, but

more often shaped into secondary decorative elements or as small precious objects.

Zitan

Zitan is an extremely dense wood which sinks in water.

It is a member of the rosewood family and is botanically classified in the Pterocarpus

genus. The wood is blackish-purple to blackish-red in color, and its fibers are

laden with deep red pigments which have been used for dye since ancient times.

The fine texture of the wood grain is especially suitable for intricate carving.

Zitan is an extremely dense wood which sinks in water.

It is a member of the rosewood family and is botanically classified in the Pterocarpus

genus. The wood is blackish-purple to blackish-red in color, and its fibers are

laden with deep red pigments which have been used for dye since ancient times.

The fine texture of the wood grain is especially suitable for intricate carving.

Early records indicate that zitan was sourced in tropical forests of southern China, throughout Indochina, and from Hainan Island. The tree grows quite slowly. Few pieces are known to be greater than one foot in width. While the tree has been considered to be extinct, new sources have been discovered in Indo-China as well as Southeast Asia over the recent years.

Decorative Stone

Decorative stone was used as a secondary material

for table top panels, decorative inlay panels, and impressionistic screen panels.

The natural imagery revealed in a slice of geological time often revealed abstract

landscape scenes or figures.

Decorative stone was used as a secondary material

for table top panels, decorative inlay panels, and impressionistic screen panels.

The natural imagery revealed in a slice of geological time often revealed abstract

landscape scenes or figures.

Soft decorative stone such as marble or serpentine

were commonly used; agate panels were also used, but much more rarely.

Soft decorative stone such as marble or serpentine

were commonly used; agate panels were also used, but much more rarely.

Paktong

Paktong, or baitong hardware was commonly used

for reinforcement and decoration. Paktong is essentially a brass alloy with a

5-10% nickel content with imparts a silvery luster and retards the tarnishing

which is typical to brass. Metalsmiths were a specialized trade distict from woodworking

carpenters.

Paktong, or baitong hardware was commonly used

for reinforcement and decoration. Paktong is essentially a brass alloy with a

5-10% nickel content with imparts a silvery luster and retards the tarnishing

which is typical to brass. Metalsmiths were a specialized trade distict from woodworking

carpenters.

Woven Cane

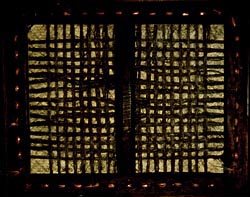

Soft, woven seats were traditional to Ming and early

Qing furniture, although the use of hard seat panels is occasionally noted in

early examples. Aside from its pliable support, the airiness of the woven bed

frame was especially comfortable during the hot summer seasons. With regard to

chairs, the customary use of woven seats gives way to increasing use of hard-panel

seats during the 18th and 19th centuries, and old soft seats were also occasionally

replaced with maintenance-free hard panels during this period.

Soft, woven seats were traditional to Ming and early

Qing furniture, although the use of hard seat panels is occasionally noted in

early examples. Aside from its pliable support, the airiness of the woven bed

frame was especially comfortable during the hot summer seasons. With regard to

chairs, the customary use of woven seats gives way to increasing use of hard-panel

seats during the 18th and 19th centuries, and old soft seats were also occasionally

replaced with maintenance-free hard panels during this period.

Seat weaving was a specialized tradition, and itinerant

specialists facilitated their frequent repair and renewal. Soft seats were produced

in several traditional styles. Occasionally, processed animal tendons were used

to weave an extremely pliant matting. Woven-rope and leather-strip seats were

common to folding stools and folding chairs. More commonly, an underwebbing of

twisted palm fiber was woven through the holes in the seat frame, after which,

split cane was woven directly on top.

Seat weaving was a specialized tradition, and itinerant

specialists facilitated their frequent repair and renewal. Soft seats were produced

in several traditional styles. Occasionally, processed animal tendons were used

to weave an extremely pliant matting. Woven-rope and leather-strip seats were

common to folding stools and folding chairs. More commonly, an underwebbing of

twisted palm fiber was woven through the holes in the seat frame, after which,

split cane was woven directly on top.

The craft of weaving cane has all

but disappeared. Modern recaning continues the underwebbing technique, however,

the finely woven mat has been replaced by sheet matting that is cut to size and

simply pinned into the holes with softwood wedges. The fiber and cane, having

been soaked for several hours before weaving, dries to a taught, yet elastic seat

panel.

- - - - - - - - -

Material

Timber and lacquer are the most widely used materials in furniture, with the lacquering technique or process having a significant affect on the value of a piece. Other materials used are stone, marble, shell, coral, pearl, ivory, bone, gold leaf or various metals. Again, all other things being equal, the harder the timber, the higher the value of the furniture (for instance, huanghuali is regarded as the hardest and most expensive timber, while pine is the softest and least expensive).

Timber

can be classified into six categories. In descending order of hardness (and value),

they are:

1. huanghuali (yellow rosewood), zitan (sandalwood), jichimu (Chicken

Wing wood)

2. hong-mu (blackwood), tielimu (ironwood), jarjingmu, wu-mu (ebony),

ying-mu (burl), hua-mu (gingko)

3. ju-mu (southern elm wood), hetaomu (walnut

wood), huang-yang mu (box wood), lung-yan mu (tiger-skin wood), zuo-mu (Oak)

4.

nan-mu, kundianmu, shizimu (persimmon)

5. yu-mu (elm), zhang-mu (camphor),

hualimu (rosewood), huai-mu (Locust), tao-mu (peach), li-mu (Pear)

6. pai-mu,

song-mu (pine), shang-mu (cedat), qiu-mu (Catalpa), duan-mu (poplar), Bai-yang

mu (paulownia), wu-tong (Kiri)

http://www.chinese-classical-furniture.com/chinese-furniture-buy.html

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Taking Care Of Chinese antique furniture

Every piece of furniture has been carefully selected by EJ Grant Antiques for your use and enjoyment. Most of the furniture is over 100 years old.

Wood is an organic substance and each species has its own characteristics in terms of color, grain, texture and smell. The first step in the care of your furniture is to understand the conditions that can cause damage. The second step is to follow some basic guidelines for care, handling and cleaning.

Causes of Damage

Handling

The

primary cause of damage to furniture is careless handling. Furniture, no matter

what size, should always be moved by grasping the sturdiest part (for example,

chairs should be lifted by the seat and table by the rail.) Items should never

be dragged as this will place stress on their legs, feet and arms.

Furniture

surfaces must always be protected from alcohol and water (drink coasters, for

instance.) If water or alcohol does come in contact with the finish, it should

be removed immediately. This is particularly important if you have a shellac based

finish. If tables are protected by glass tops, felt or plastic tabs should be

used so that the glass does not stick to the furniture finish.

Environment

All

wood finishes are subject to change when exposed to light Depending on the type

of finish and wood, this can range from darkening to fading. If objects are left

in the same position on a piece of furniture for a long period of time, uneven

facing will occur. Where possible, direct sunlight should be avoided as the heat

generated may cause damage by softening or cracking the finish.

Temperature

and Humidity

Wood is a porous material and absorbs water when humidity levels

are high. This causes the wood to swell. Conversely, wood shrinks in a dry environment.

This causes movement within the structure of the wood and can produce cracks,

veneer lifting and gaps in joints. Rapid fluctuations in humidity and temperature

cause the greatest amount of damage. Furniture can withstand considerable variation

in temperature and humidity provided the change occurs at a slow rate. Remember,

houses prior to the 20th century did not have air conditioning and central heating

and by and large the furniture survived quite well. The main damage was generally

done to the feet.

In an ideal world, the recommended temperature and humidity levels should be:

Temperature Relative humidity

Winter 70° F 35 - 45%

Summer 70° - 75°/font>

F 55 - 65%

Cleaning

Contrary

to common belief you do not have to "feed" the wood, and the following

information will assist you to keep your furniture in prime condition.

Do

not use a polish containing silicone. Just dust with a soft dry cloth.

Once

or twice a year you may wish to wax the furniture with a good polish containing

beeswax and carnauba wax. Apply sparingly, and buff with a soft cloth.

Do

not use kitchen cleaners as they may scratch the finish.

Do not use chemical

cleaners, Pledge?or other commercial cleaners.

Conclusion

If you follow the above guidelines your furniture will give you pleasure for a very long time. However, furniture can become damaged. In such a case, you should approach a furniture restorer/conservator who is experienced in restoring furniture similar to what you have. A list of conservators can be obtained from the American Institute of Conservation or from the Washington Conservation Guild (In the Washington, DC area.)

Maintenance

Tips

Taking good care of your furniture will enhance its practicality as well

as its value. Central to this is understanding how a piece is constructed and

decorated, and—if it is made of wood—how this natural material reacts

to its environment. Appropriate use, swift repair in response to accidental damage,

and the right environmental conditions should ensure that your furniture remains

in good condition.

Cleaning

Furniture

generally requires a minimum of cleaning. A weekly light dusting together with

a twice-yearly wax polishing—if the piece is made of wood—should suffice.

Particular care should be taken with inlays, marquetry and veneers, in case your

polishing cloth lifts a piece. If this does happen, keep the broken piece and

contact a restorer. Lacquer is also vulnerable to excessive handling. Gilded fittings

should not be cleaned since the gilt may easily be removed.

Moving

The

definition of the word "furniture" is a "moveable article to equip

a room or a house"—its portability is central to its function. Considerable

care should therefore be taken when handling furniture. At least two people should

lift larger pieces, balancing the load and supporting the main carcass or frame

rather than grasping chair backs or tabletops, for example. Never drag an item

of furniture; even pieces with castors should be lifted when possible since legs

can be easily broken. Drawers and other detachable elements can be removed to

lighten the load, and doors should be tied shut.

Positioning

Wood

is particularly susceptible to the effects of light and heat. Direct sunlight

causes wood to fade and lose its color; heat warps and shrinks wood, causing veneers

to lift from the carcass. Always keep pieces away from fireplaces and radiators.

If it is impossible to avoid direct sunlight, use a protective cover on the furniture,

a thick blind on the window, or apply ultraviolet-absorbent filters to windowpanes,

which will prevent these damaging rays from entering the room.

In addition, antique furniture is sensitive to humidity. The ideal room climate is 64°F (18°C) and 50% humidity, with a 20% variation. Humidifiers are available at hardware stores and will help to maintain and monitor humidity levels.

Should your furniture suffer shrinkage or splitting, it is essential that you adjust the environmental conditions before repairs are carried out. Otherwise, further splitting may occur.

Restoration

It

is natural that the enjoyment and use of antique furniture might lead to accidental

damage, such as stains, loose joints, or broken inlays and veneers. Should this

occur, consult a reputable furniture restorer.

Wood

is a natural living product, therefore, wood furniture will "breathe"

in response to changes in the atmosphere. Rapid or extreme fluctuation in temperature,

humidity or direct sunlight may cause cracking, splitting, and/or warping of the

piece. The ideal condition for furniture is a stable atmosphere with fluctuations

ranging between: a relative humidity of 40 - 70% ; a temperature of 15 - 25 degree

(Centigrade) . Operating a humidifier or placing a glass of water inside or underneath

the furniture will help to maintain the right level of humidity. Wood as a plant

contains water in its structure. Throughout our manufacturing process, substantial

amount of water would have been eliminated from the wood to make it stable. However,

wood still expands or contracts as related to the relative humidity in the air.

One exception is wood that has undergone chemical treatment.

The design of

Chinese furniture has already catered to this behavior of wood. In particular,

a large surface is usually made with floating panel framed by wood members on

four sides. The floating panel can expand or contract but still has its surface

secure and intact. In an extremely dry environment, the contraction, however,

might reveal certain "un-colored" portion of the tongue that is inserted

into the wood members. If the furniture is moved to a higher humidity environment,

the wood will expand and the "un-colored" portion will be concealed

again. This is a normal behavior for Chinese furniture.

The ideal condition

for furniture is a stable atmosphere with relative humidity fluctuations of 40

- 70 percent, and a temperature from 60 - 80 degrees Fahrenheit. Operating a humidifier

or putting a glass of water inside or underneath the furniture may help to maintain

humidity.

Strong sunlight can cause fading or other changes. If you leave

objects in a permanent position on the furniture, uneven fading may also occur.Avoid

placing furniture next to radiators, hot air vents, air conditioners, or open

windows. Do not place hot containers directly onto the surface of the furniture.

Careless handling of the furniture may also cause damage.

Wood is an organic

substance, and each species of wood has individual characteristics such as color,

texture, and smell. We apply appropriate finishes on each piece with those characteristics

in mind, so the finish and the design of the wood enhance one another and work

together harmoniously.

Use dry cloth, soft brush or the brush of a vacuum

cleaner to remove dust on the furniture. If needed, use a dry or mild damp cloth

to wipe away dirt or stains. This is the only cleaning you need for the furniture.

Never use too much water to clean the furniture.

There is normally no need

to re-wax the furniture very offen . Just wiping with a dry cloth can restore

the shimmer. However, if there has been too much stain on the surface, or the

furniture has lost its shimmer altogether, re-wax is then needed. Use only a thin

layer of soft "paste like" furniture wax. High quality furniture beeswax

is easily available in the market. Never use the spray type furniture wax, otherwise

you will have to say good-bye to the beautiful furniture color.

For certain

finish of our pieces , the paint and color is made very thin to best reveal the

wood grains. The furniture surfaces therefore cannot withstand too much scratching.

So if objects such as lamps or vases are to be placed on furniture top, it is

highly recommended to shield them with soft padding on their bottom surfaces.

Do not use abrasive kitchen cleaners, as they will scratch the surface.

Do

not use chemicals or other commercial cleaners on furniture.

http://www.chinese-classical-furniture.com/chinese-furniture-care.html