Terebess

Asia Online (TAO)

Index

Home

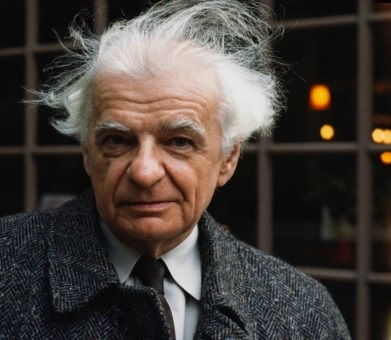

Yves Bonnefoy (1923-2016)

LE HAÏKU, LA FORME BRÈVE ET LES POÈTES FRANÇAIS

Une conférence d'Yves Bonnefoy au Japon en septembre 2000

Masaoka Shiki International Haiku Awards Project

https://web.archive.org/web/20031004020410/http://www.shiki.org/2000/french.pdf

English versionI

Mesdames, messieurs, que mes premiers mots soient pour remercier votre assemblée de l’honneur qu’elle me fait en me conviant à la réunion d’aujourd’hui, et en voulant bien considérer que je suis digne de prendre part à sa réflexion sur le haïku, et plus généralement sur la forme brève. Je vous prie de penser que ce n’est pas sans un sentiment d’insuffisance que je m’approche ainsi de l’expérience poétique dont votre civilisation et ses grands poètes sont les maîtres incontestés. Personne au monde comme des Japonais n’ont su faire retentir dans les consonances et dissonances de quelques mots l’entière réalité, à la fois sociale et cosmique. Vous avez marié l’infini à la parole d’une façon qui fascine, bien au delà de vos frontières, et en France en tout cas, et depuis longtemps, nous sommes nombreux à écouter vos poètes, à commencer par Bashô, lequel, et j’y reviendrai, a beaucoup compté dans ma propre vie.

Les poètes français aiment le haïku, et c’est d’ailleurs par la constatation de ce fait et quelques réflexions sur son sens que je commencerai ma petite contribution à votre recherche. Les poètes français aiment le haïku, ils lui ont même accordé depuis quelque cinquante ans une attention spécifique, avec un effort très sérieux pour en comprendre l’esprit et en tirer un enseignement pour leur propre rapport au monde, ce qui signifie qu’ils sont en mesure, jusqu’à un certain point, d’en pénétrer au moins quelques grands aspects.

Or, et voici ma première remarque, c’est évidemment par le seul truchement des traductions que nous connaissons ces poèmes, et on serait donc tenté de penser que ce qui en est l’essentiel nous est refusé de ce fait même, pour plusieurs raisons qu’il serait vain de sous-estimer. D’abord, il y a entre vos poètes et nous la différence des langues, qui fait que de grandes catégories de pensée et beaucoup d’autres notions de moindre importance, mais souvent présentes dans les poèmes, ne sont pas localisées de même façon dans le réseau d’ensemble des relations que nos paroles entretiennent avec le monde comme elles l’ont mis en place. Il peut s’agir d’une disparité des connotations et dénotations qui caractérisent le mot japonais et le mot français que l’on veut mettre en rapport, mais il arrive aussi, j’imagine, que ce qui pour vous peut être dit, d’une façon immédiate et comme intuitive, par une seule notion, ne soit compréhensible en français qu’au prix d’un processus d’analyse difficile à mener à bien et aboutissant, en tout cas, à plusieurs idées que nous ressentons comme distinctes et dont il nous faudra donc chercher à comprendre la relation, jusqu’alors par nous inaperçue. Et quel problème est-ce là, quand cette sorte de situation apparait dans la traduction d’un poème bref, où nul développement réflexif n’est concevable ! Surtout si ces notions inconnues de nous portent sur des aspects fondamentaux de votre pensée de la poésie ou de votre perception du monde le plus élémentaire.

Et tout près de cette question de la disparité des vocabulaires, voici celle de nos syntaxes, que l’on ne peut imaginer plus lointaines l’une de l’autre. Quelle distance entre la syntaxe des langues de la famille indoeuropéenne et votre façon de produire le sens à partir des notions, des informations particulières ! Or, c’est dans ces rapports entre mots que l’intuition qui vous permet de rapprocher des impressions au départ très dissemblables peut se frayer sa voie dans les haïkus, j’imagine, allant plus aisément, plus rapidement que nos phrases analytiques au sentiment de l’unité, ou du rien, qui est au cœur de toute vraie poésie. Il faut peut-être toutes les strophes de l’Ode à un rossignol, de Keats, il faut peut-être toutes celles du Cimetière marin, de Paul Valéry pour accéder à l’impression de chant mélodieux dans la nuit ou de mer déserte au soleil qu’un Bashô ou un Shiki sauraient évoquer en dix-sept syllabes. Voilà qui n’augure rien de bon pour la traduction en français ou anglais de ces dernières.

Et qui plus est, la notation graphique des mots est pour vous constituée d’idéogrammes, de signes gardant souvent un peu, dans le ur apparence, de la figure des choses, et le haïku est bref, ce qui permet d’en voir tous les caractères d’un seul regard, d’où suit que le poète pourra faire passer à travers ses mots un frémissement de leur figure visible qui aidera à sa perception du plus immédiat, du plus intime, dans la situation qu’il évoque. Ce poète sera un peintre. Il pourra ajouter au savoir propre des 14 - 15 mots ce savoir d’au delà les mots que permet au peintre le regard qu’a approfondi une méditation silencieuse des grands aspects du lieu naturel. Que va-t-il rester de cette intuition dans les mots de nos traductions, séparés comme ils sont chez nous de l’aspect sensible des choses mêmes qu’ils nomment par la nature foncièrement arbitraire et abstraite de la notation alphabétique ? Notre écriture abolit le rapport immédiat avec le monde, c’est cela qui lui vaut son aptitude toute particulière aux sciences de la matière, mais c’est cela aussi qui rend la poésie difficile, et j’avoue que je vous envie de disposer des idéogrammes. D’autant qu’ils me paraissent garder ouvert au centre des lignes qui se composent dans chacun d’eux un vide où se signifie le rien, l’expérience du rien qui est, je l’ai déjà dit, un souci majeur de toute pensée poétique, même si celle-ci cherche dans l’existence vécue ce qui peut nous donner une raison d’exister sur terre. Il y a une lucidité de l’esprit dans les signes qu’emploie votre écriture, et cette lucidité est donc au début de vos travaux poétiques, alors que chez nous elle ne paraîtra qu’à la fin, si toutefois le poète ne s’est pas perdu en chemin.

Bien difficile la traduction du haïku dans nos langues occidentales, décidément! Je crois même qu’il faut se résigner à penser que cette traduction est impossible.

II

Et pourtant il y a donc eu, il y a toujours, ce grand intérêt dans notre pays pour le haïku, pourquoi?

Peut-être, tout simplement, parce que ses traductions, tout appauvries qu’elles soient, restent de superbes exemples de forme brève, ce qui, dans la situation où nous sommes, en Europe, a déjà en soi beaucoup de valeur, comme exemple et comme encouragement.

Qu’est-ce qui caractérise, en effet, un texte bref? Une capacité accrue de s’ouvrir à une expérience spécifiquement poétique.

Ne parlons plus pour l’instant des seuls poèmes limités à dix-sept syllabes, et riches d’un aspect graphique autant que d’un sens, pensons à toutes les oeuvres qui ont tenté de dire avec peu de mots, et aussi bien en français qu’en japonais, une émotion, une intuition, un sentiment, une perception. Il est clair que dans cet espace verbal de peu d’étendue, et qui doit se suffire à lui-même, il ne peut y avoir de récit, sinon dans des allusions qui n’en évoqueront un que de loin, et d’un seul coup. Et cela signifie, comme conséquence immédiate, que les mots du poème bref sont délivrés d’une certaine approche des événements et des choses, celle qui, dans les récits, les enchaînent dans une suite de causes et d’effets, au risque qu’on ne les sache plus, ces situations de la vie, que par la voie de la sorte de pensée qui analyse, généralise: qui ne connaît la réalité particulière que du dehors. Le poème bref est à l’abri de cette tentation de prendre recul par rapport à l’impression immédiate. Il est ainsi plus naturellement qu’aucun autre en mesure de coïncider avec un instant vécu.

Et au sein de cet instant il y a aussi qu’il nous oblige à ne considerér que très peu de choses, puisqu’il ne contient que très peu de mots: si bien que les relations qui peuvent dans cet instant de notre existence s’être établies en nous entre ces choses du monde vont pouvoir se déployer librement, avec toutes leurs vibrations, d’autant plus aisément audibles qu’on n’y est plus prisonnier de la pensée conceptuelle. Nous sommes rapatriés dans ce sentiment d’unité que le long discours nous ferait perdre. Or, cette expérience d’unité, d’unité vécue et non pas seulement pensée, c’est évidemment la poésie. On peut oublier cela, en Occident, parce que nos traditions religieuses, celles du Dieu personnel, transcendant par rapport au monde, ont séparé l’absolu de la réalité naturelle, mais ce n’en est pas moins, cette approche de l’Un dans chaque chose, l’émotion suprême à laquelle instinctivement tous les poètes s’attachent.

La forme brève peut être ainsi plus qu’aucune autre le seuil d’une expérience spécifiquement poétique. Quand un poème adopte une forme brève, il se tourne déjà, de ce simple fait, vers ce qui peut être poésie dans notre rapport au monde. 16 - 17

III

Or, je dois le souligner maintenant, la forme brève n’a pas été bien souvent présente dans l’histoire de notre poésie. Précisément parce que la réalité a longtemps été ressentie comme la simple création de Dieu et non le divin comme tel, la pensée théologique ou philosophique a occupé l’esprit des Européens bien davantage que l’écoute du bruit du vent ou le regard sur la feuille qui tombe, et nos poèmes doivent donc être assez longs pour qu’une pensée s’y développe. Cela est vrai même dans le cas de poèmes qui semblent relativement courts, comme le sonnet, qui a été si important pendant plusieurs siècles dans l’histoire de l’Occident. Le sonnet a bien plus que dix-sept syllabes, il n’a tout de même que quatorze vers, et c’est pour nous un poème bref, mais son effet n’est pas pour autant celui d’une forme brève. Car il commence par deux strophes d’une certaine structure formelle, deux groupes de quatre vers, puis continue et s’achève par deux autres strophes qui sont cette fois de trois vers, ce sont des nombres impairs qui succèdent à des nombres pairs, et entre les deux parties il y a donc comme une rupture qui semble vouloir signifier, et qui a été fréquemment utilisée pour signifier quelque chose, effectivement, si bien que le sonnet, aussi limité soit-il, est une pensée qui se développe, il y a même en lui de quoi ressembler au syllogisme, avec ses prémisses suivies de ses conclusions. Ah, bien sûr, l’expérience véritablement poétique est possible dans un sonnet autant que partout ailleurs. On peut même y éprouver, au neuvième vers, le passage du pair à l’impair comme un réveil dans l’esprit du sentiment du temps qui passe, c’est-à-dire de l’existence, c’est-à-dire de l’instant, lequel est une expérience possible de l’immédiat. Mais ce n’est pas un hasard si le sonnet a été pendant si longtemps dans son histoire intimement lié à la vogue du Platonisme, il est un discours au moins autant qu’un poème.

Et ne parlons pas de quelques formes assurément brèves qu’il y a eu dans notre littérature, comme par exemple l’épigramme. Car dans ce cas il ne s’agit que de faire valoir une idée de façon brillante, et l’on n’est donc pas là en rapport avec la réalité du dehors, avec la nature, mais dans l’espace de la conversation, parmi des causeurs qui ne s’intéressent qu’à des idées et à la belle langue où ces idées prennent forme. La brièveté, c’est alors pour créer la surprise, qui fait valoir une intelligence, et les vrais poètes ne peuvent éprouver pour cette sorte-là de brièveté que de l’aversion, ils la jugent à bon droit futile, ils n’ont pas rencontré dans ces occasions une forme brève authentique.

La conséquence, bien malheureuse, c’est que l’on a fini, au XIXème siècle, par considérer ceux des poètes qui écrivaient des poèmes courts, sans autre ambition que d’exprimer une impression fugitive, comme des auteurs eux aussi futiles, ou en tout cas mineurs, inférieurs à ceux qui écrivaient des oeuvres plus vastes. D’autant que ces poètes dits mineurs se laissaient persuader qu’ils l’étaient effectivement. Je pense à un Toulet, qui n’est certes pas un grand poète, mais qui fit vibrer dans ses Contre-rimes des sons de grande subtilité. Borges, qui s’y connaissait en poésie, admirait beaucoup Toulet, mais en France on ne lui a pas encore attribué beaucoup d’importance. Presque la même chose pourrait être dite de Verlaine. Cette fois personne ne doute qu’il s’agisse avec lui d’un grand poète, néanmoins on fait volontiers de son œuvre une lecture qui la réduit aux moments d’irresponsabilité de ses journées les plus misérables, au lieu de percevoir que sa poésie est capable de la plus extrême perceptivité ou même, comme dans Crimen Amoris, de poser avec force dans cette fois un discours très éloquent les problèmes de l’être-au-monde. Verlaine ! Je puis remarquer au passage que si j’avais à citer des poèmes français qui s’apparentent au haïku, je penserais tout de suite à plusieurs des siens. N’y a-t-il pas quelque chose que vous pouvez reconnaître dans une notation comme:

L’ombre des arbres dans la rivière embrumée,

Meurt comme de la fumée,

Tandis qu’en l’air, parmi les ramures réelles,

Se plaignent les tourterelles ?Notez pourtant que ces vers de Verlaine ne sont pas à eux seuls un poème en soi, ils font partie d’un texte plus long, et pour trouver de la brièveté dans notre passé poétique, il faut plutôt, comme le cormoran dans le lac, plonger dans des oeuvres longues, y retrouvant des points où le poète s’est arrêté, levant ses yeux de son discours, regardant autour de lui. La brièveté était alors, pour lui, un événement imprévu, non voulu d’avance. Cela ne l’empêchait pas moins, j’en suis sûr, de ressentir bien des fois qu’il 18 - 19 était là au meilleur de son projet poétique.

Ceci étant, la société française et les convictions religieuses avaient commencé, à l’époque romantique, de changer d’une façon favorable à l’appréhension poétique de la réalité. Accompagnant un certain déclin de l’idée chrétienne du monde, la pensée d’une nature riche d’une vie mystérieuse encourageait les poètes à s’attacher aux impressions qu’ils en recueillaient, et ainsi l’expérience proprement poétique pouvait s’affirmer aux dépens des aspects plus discursifs des poèmes, ce qui permettait de mieux comprendre la valeur et les capacités de la brièveté poétique, et même d’en faire usage d’une manière consciente, en considérant que ce pouvait être le cœur même de la recherche. C’est précisément ce qui a lieu chez Rimbaud, qui a commencé d’écrire par de longs poèmes riches d’idées, et en est venu, très rapidement, aux notations fulgurantes de ses poèmes de 1872 et des Illuminations. On peut dire que ces poèmes de Rimbaud sont les premières grandes créations de forme brève en français, chez un poète que l’on pourrait d’ailleurs comparer, me semble-t-il, à certains poètes du Japon par sa façon de vivre. Et ils ont constitué pour notre modernité un grand exemple, mais ils restèrent tout de même une exception, et pour ceux qui chez nous savent mieux, aujourd’hui qu’hier, que la perception du monde sensible est au cœur de la poésie, il fallait assurément d’autres témoignages encore.

Telle est la raison de l’intérêt pour le haïku que l’on a vu se développer en France dans la deuxième moitié de notre XXème siècle, et qui est aujourd’hui toujours aussi fort. Cet intérêt s’est établi quand les textes et une certaine idée des poètes japonais commencèrent à circuler, grâce à des traductions ou des commentaires, et c’est ainsi que le livre de Blyth, Haïku, a joué un grand rôle auprès de certains d’entre nous. Ces poèmes n’avaient nullement besoin pour intéresser le lecteur français de préserver dans la traduction toute leur richesse, puisque le simple fait d’être bref, de se limiter à un seul regard rassemblant quelques grandes réalités du monde naturel ou social dans une seule impression, était maintenant ce dont on pouvait comprendre la valeur spécifiquement poétique. Et rien n’empêchait, de surcroît, les lecteurs de ces poèmes, de s’informer des auteurs, de prendre conscience des moines zen, de se pénétrer d’une spiritualité qui répond très fortement aux besoins de l’esprit dans notre société moderne qui a appris à comprendre que beaucoup de ses convictions religieuses ou métaphysiques ne sont que des mythes. La pensée qu’il n’y a rien sous les phénomènes, que la personne humaine n’a pas à se considérer supérieure à la nature, c’est bien ce que l’on doit accepter désormais, et cela permet d’entendre le haïku. Je n’hésiterai pas à dire que les meilleurs des poètes français depuis les années 50 ont réfléchi à cette forme de poésie. Il ne s’est pas agi de ce qu’on pourrait appeler une mode du haïku , mais de la prise de conscience d’une référence nécessaire et fondamentale, qui ne peut que rester au centre de la pensée poétique occidentale.

IV

Et ce qu’il faut que je vous dise maintenant, c’est quelle forme concrète a pu prendre cette influence. Il va de soi qu’il ne s’agit pas pour nous d’imiter le haïku, c’est-à-dire d’écrire des poèmes aussi brefs que possible, retrouvant à peu près le nombre des mots d’un haïku quand il est traduit en français. Quelques poètes ont tenté cela, de façon naïve, mais c’est se tromper de voie. Nous n’avons pas comme vous l’aspect visible des signes pour soutenir l’intuition du poète, et les aspects conceptuels du vocabulaire continuent donc de prédominer dans nos mots, même quand ceux-ci ne sont employés qu’en petit nombre, si bien que pour accéder à la profondeur et à la limpidité d’une notation semblable à celle des maîtres du haïku il faut avoir mené dans notre recours aux substantifs et aux adjectifs une longue lutte qui doit être assez présente dans le poème pour que le lecteur l’y reconnaisse, la revive, et apprenne ainsi avec le poète à voir comme celui-ci a réussi à le faire. Comme dans le passé de notre poésie nationale, la brièveté est encore aujourd’hui en France un état passager auguel il arrive que l’on accède, mais rien de plus. Nous n’avons la possibilité que de nous mettre en mouvement vers elle, au sein de textes qui restent longs, étant en somme le journal de notre recherche, la tentative ardue et jamais finie de la clarification de nous-mêmes.

J’ajoute, en ce point, qu’il y a d’ailleurs dans le poète français une conscience de soi comme personne qui reste forte, quelle que soit la qualité d’évidence des leçons d’impersonnalité, de détachement de soi qu’il 20 - 21 rencontre dans une poésie japonaise fortement imprégnée par le bouddhisme. Ce n’est pas aisément que l’on oublie en Occident l’enseignement du Christianisme, qui fut de dire que la personne humaine a une réalité en soi et une valeur absolue. La sensibilité poétique reste chez nous absorbée par la réflexion du poète sur soi, et les grands poèmes demeurent pris, par conséquent, dans une ambiguïté, partagés entre le souci de la destinée personnelle et le besoin de plonger dans la profondeur du monde naturel et cosmique, où cette destinée n’aurait plus de sens. Exemplaire de cette ambiguïté l’œuvre souvent admirable de Pierre-Albert Jourdan qui est mort prématurément il y a une dizaine d’années. Dans des oeuvres comme l’Entrée dans le jardin ou les Sandales de paille -- un titre, ce dernier, où vous reconnaissez une allusion à la vie des poètes-moines du Japon - il y a simultanément l’héritage de saint François d’Assise et des grands récits de Bashô.

Mais vous attendez peut-être de moi un témoignage plus personnel. Et je vous dirai maintenant que cet intérêt pour la forme brève et plus spécialement pour le haïku, c’est ce que j’ai vécu moi-même. D’abord ce fut une façon de lire les auteurs de notre passé français. Je me souviens de mon émotion quand je rencontrai dans un recueil de textes du moyen âge ce qui n’était plus qu’un fragment, seul préservé de tout un manuscrit à jamais perdu, mais ce fragment me fut toute la poésie, d’un seul coup. C’étaient ces simples mots: Hélas, Olivier Bachelin . Trois mots seulement, et même deux des trois pour ne former ensemble qu’un seul nom propre, celui de cet Olivier Bachelin. Mais quelle fulgurance, dans si peu de parole ! D’une part, avec Olivier Bachelin , un être qui a vécu, qui a peut-être aimé, qui a connu joie et souffrance, mais dont on ne sait absolument rien, ce qui fait qu’il peut signif ier notre condition à chacun, en ce que celle-ci a de plus fondamental. Et d’autre part ce hélas qui indique qu’un malheur lui fut associé, ce qui nous rappelle les vicissitudes de l’existence, le hasard qui lui est inhérent, le néant qui rôde sous toute vie. Les deux pôles de notre souci sur terre, avec entre eux ce brusque rapprochement où se marque l’identit’e de l’être et du néant. Et on lève alors sur le monde un regard délivré des illusions, un regard sans recul, un regard qui voit tout ce qui est -- c’est-à-dire n’est pas -- comme une immédiateté silencieuse. Ce Hélas, Olivier Bachelin , dans son laconisme extrême, me fut la poésie bien plus directement et plus fort que beaucoup de longs poèmes, et je comparerais ces mots à un haïku si je n’avais à me souvenir qu’ils restent hantés par ce rêve occidental que la personne soit comme telle une réalité absolue.

Ce rêve était en moi aussi bien, et quand j’ai commencé d’écrire moimême sérieusement, avec aussitôt des poèmes brefs, très brefs, ceux qui constituent la première partie de mon premier livre, Du mouvement et de l’immobilité de Douve, publié en 1953, j’ai dû constater que ces textes avaient eux aussi cette préoccupation de la destinée personnelle comme une de leurs composantes, ce qui les retenaient de rencontrer vraiment la réalité en son unité, et me demandait, en somme, de m’engager dans un long travail de clarification intérieure, où le moi qui s’obstine dans ses illusions aurait à se dissiper dans l’évidence du monde. Travail évidemment impossible, en tout cas inachevable, au moins pour moi, mais qui ouvrait un chemin que je crois spécifique de la poésie occidentale moderne, et qui montre comment nous pouvons dans nos perspectives propres rencontrer le haïku, rencontrer cet enseignement tout ensemble de poésie et de sagesse. Ce sera en des moments où, au sein de notre écriture, là où le moi continue de monologuer, on aura réussi, à cause de quelque événement dans nos vies, à voir se dresser devant nous la réalité silencieuse, à la fois très étrangère à notre souci et mystérieusement accueillante. Un de ces moments paraît dans le livre que j’ai cité, au moins je le comprends de cette façon, et il est ainsi pour moi ce qui, pour la première fois, eut dans ce que j’ai écrit assez de parenté avec le haïku pour que je puisse me permettre de vous le citer. Ce sont simplement deux vers mais qui constitue donc à mes yeux tout un poème, que j’ai présenté séparé des autres, seul sur sa page. Il dit:

Tu as pris une lampe et tu ouvres la porte,

Que faire d’une lampe, il pleut, le jour se lève,et vous voyez ce qui y est en jeu: la découverte au matin de la pluie qui couvre la campagne, le moi qui dans cette grande évidence silencieuse se détache soudain de soi, si bien que plus n’est besoin de la lampe qui aurait servi à la poursuite d’une de ses activités ordinaires, et une lumière nouvelle qui paraît, ou plutôt la lumière de chaque jour qui paraît de façon nouvelle. Dans cet instant sur le seuil de la maison, après une 22 - 23 nuit tourmentée peut-être, la brièveté était nécessaire pour rester fidèle à mon expérience. Ajouter quoi que ce soit à ces quelques mots n’aurait fait que me la faire oublier.

Et je n’ai pas cessé par la suite de me retrouver loin de ce jour, de cette évidence, mais au moins je ne pouvais plus méconnaître ce qu’était la poésie, ce qui me préparait plus encore qu’auparavant à la lecture des haïkus, et j’étais donc prêt à aimer Bashô quand nous avons eu en français dans les années 60 une traduction de La sente étroite du bout du monde. Je me souviendrai toujours de mon saisissement quand j’ai lu les premières lignes du livre. Mois et jours sont passants perpétuels... Moi-même, depuis je ne sais quelle année, lambeau de nuage cédant à l’invite du vent, je n’ai cessé de nourrir des pensers vagabonds . Avec cette traduction de Bashô, avec l’anthologie de haïkus établie plus tard par Roger Munier, c’était la grande poésie japonaise qui prenait la parole en France. Je ne doute pas qu’elle va continuer de parler à nos préoccupations les plus intimes. Je puis même penser qu’il y aura dans notre poésie une expérimentation des poèmes brefs qui sera la conséquence directe des haïkus, en ce que ceux-ci ont d’universellement, d’internationalement valable: non une forme précise mais un esprit, une immense capacité d’expérience spirituelle.

Merci, encore une fois. Ce que je dois aussi à l’attention que vous avez bien voulu m’accorder, c’est de prendre mieux connaissance de l’œuvre des poètes de Matsuyama et en particulier de Masaoka Shiki. Il est souhaitable que ces poètes soient mieux connus en France, et je suis heureux de me retrouver grâce à vous en position d’en parler dans mon pays. Il est souhaitable aussi que votre projet d’une réflexion internationale sur le haïku et la forme brève se développe en particulier avec les nations européennes, et j’espère que je pourrai rapporter de ces journées parmi vous des programmes précis qui permettront de nouveaux échanges, pour le plus grand bien de la poésie qui est notre bien commun, et un des rares moyens qui nous restent de préserver la société des dangers qui pèsent sur elle.

Yves Bonnefoy

Memorial Lecture by Yves Bonnefoy

Haiku, Short Verse and French PoetsDistinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen, I would first like to express my sincere gratitude to your assembly for the honor of being invited to today's gathering, and of being considered worthy to take part in its reflection on haiku and the short verse form in general. However, I would like you to be aware of the fact that it is not without a feeling of inadequacy that I thus approach the poetic experience of which your civilization and its great poets are the undisputed masters. No people in

the world has ever equaled the Japanese in making the whole of reality, both social and cosmic, echo in the consonance and dissonance of a fewwords. You have married the infinite to the word in a way that fascinates people far beyond your borders, and certainly in France for a long time many of us have listened to your poets, beginning with Basho, who, as I shall explain shortly, has counted for much in my own life.French poets like haiku, and it is with this observation and a few reflections on its meaning that I would like to begin my modest contribution to your investigation. French poets love the haiku, and for

about fifty years they even have devoted particular attention to it, making serious efforts to understand its spirit and draw lessons from it for their own relation to the world, which means that to a certain extent they are capable of penetrating at least some of its major aspects.However - and this is my first observation - it is, needless to say, only through the medium of translations that we are acquainted with these poems, and one would therefore be tempted to think that what is most essential to haiku is thereby denied to us, for a number of reasons that cannot be

lightly dismissed. First of all, there is the difference of language between your poets and us, as a result of which major categories of thought and many other less important notions, often present in the poems, do not hold the same position within the whole network of relations that our words

maintain with the world as they have constructed it. There may be disparity between the connotations and the denotations that characterize the Japanese and the French words that one wishes to bring together, but it also happens, I imagine, that what in your language may be expressed immediately and intuitively in one single notion, can only be understood in French at the cost of a process of analysis that is difficult of accomplishment, and leading, in any case, to a number of ideas that we feel to be distinct and whose hitherto unnoticed relationship we will in any event have to try and understand. What a great problem this becomes when this kind of situation occurs in the translation of a short poem, where unfolding reflection is inconceivable! Above all when these unfamiliar notions bear on fundamental aspects of your poetic thought or your most basic perception of the world.Closely related to this problem of the disparity of the vocabulary, there is the disparity of the respective syntaxes, which are further removed from one another than anything one can imagine. What a distance separates the syntax of the Indo-European languages and the way Japanese produces meaning from notions and specific data! Now, it is through these relations between words that the intuition which enables you to connect initially very distinct impressions, can open up a path to haiku, leading, I imagine more smoothly and more rapidly than our analytical phrases, to the feeling of unity or nothingness which lies at the heart of all real poetry. Perhaps it requires all the stanzas of Keats's Ode to a Nightingale, perhaps it takes all the stanzas of Le cimetiere marin by Paul Valery, to achieve the impression of a melodious song in the night or of the deserted sea in the sun, which a Basho or a Shiki could have evoked in seventeen syllables. All this augurs ill for any attempt at translating these seventeen syllables into French or English.

Moreover, in Japanese the graphic representation of words is based on ideograms, on signs that often have preserved in their appearance something of the shape of things, and the haiku itself is short, which allows the reader to take in all its characters at a glance, so that the poet is able to impart through his words a vibration of their visible shape that will assist his discernment of the most immediate, the most intimate in the situation that he is evoking. That kind of poet is therefore a painter. He is able to add to the actual knowledge of words the knowledge of what lies beyond words, a knowledge that grants the painter a regard deepened by silent meditation of the great aspects of natural space. What will remain of that intuition in the words of our translations, separated as they are from the sentient aspect of the very things they denote by the fundamentally arbitrary and abstract nature of alphabetical notation? The Western writing system eliminates direct relations with the world, and it is that which comprises its particular suitability for the physical sciences, but which at the same time makes poetry so difficult, and I confess that I envy you your ideograms. All the more so because they seem to me to keep open, in the center of the lines which make up each of them, a void signifying nothingness, the experience of nothingness which is, as I have already said, a major concern of all poetic thought, even when that thought seeks out in lived existence whatever can provide us with a reason to exist on earth. There is a mental clarity in the signs that your writing

system uses, and that clarity is at the forefront of your poetic works, while in the West it only comes in at the end, at least if the poet has not lost his way in the process.It is indeed very hard to translate haiku into our Western languages. I even think that we have to resign ourselves to the idea that it is impossible to translate them.

II

And yet, in France, for a long time, there has been and there continues to be a great interest in haiku: why is that?

It may be, simply, because the translations of haiku, however poor reflections of the original they may be, remain superb examples of short verse, which, in the situation in which we find ourselves in Europe, itself has tremendous value, both as an example and an encouragement.

What is it in fact that typifies a short text? It is a heightened capacity to open oneself up to a specifically poetic experience.

Let us for a while not limit our discussion to poems of only seventeen syllables, as rich in graphic features as they are in meaning, but let us consider all kinds of writings that have endeavored to express in few words, either in French or in Japanese, an emotion, an intuition, a feeling, a perception. It goes without saying that in this narrow verbal space, that must perforce be self-sufficient, there is no room for narrative, except by way of allusions, that can only suggest indirectly and in a single stroke. And the immediate consequence is that the words of the short poem are freed from one particular approach to events and things, meaning that approach which in stories links these events and things in a sequence of causes and effects, with the danger that one no longer knows these situations in life, except through the kind of thinking that analyzes and generalizes: the kind that only knows particular reality from the outside. The short poem is preserved from the temptation to hold one aloof from the immediate impression. Thus more than any other form it is capable of coinciding with a lived moment.

And within that moment we are bound to consider only very few things, since the poem contains only very few words: as a result, in this moment of our existence, certain relations between those things of the world may have formed within us, and they will be enabled to unfold freely, with all their

vibrations, all the more audible as one is no longer a prisoner of conceptual thinking. We are drawn back into that feeling of unity of which a long discourse would deprive us. This experience of unity, of unity lived and not simply thought, is clearly poetry. We tend to forget this, in the West, because our religious traditions, those of a personal God who transcends the world, have separated the absolute from natural reality, yet even so, this drawing near of the One in every single thing remains nonetheless the principal feeling to which all poets are instinctively drawn.Thus, more than any other form, the short verse form is capable of being the threshold of a specifically poetical experience. When a poem adopts a short form, by this simple fact it directs itself toward that which may be poetry in our relation to the world.

III

However, I have to point out that the short poetic form has not often been present in the history of Western poetry. Precisely because for a long time reality has been conceived of as the mere creation of God rather than the divine itself, theological and philosophical thought has occupied the

European mind to a much greater extent than listening to the sound of thewind, or gazing at falling leaves, and our poems therefore have to berather long for a thought to unfold. That is true even for poems that seem to be comparatively short, like the sonnet, which for centuries has played a major role in Western history. The sonnet, though it has much more than seventeen syllables, has only fourteen lines and in the West it is considered a short poem, which does not mean that its effect is that of a short verse form. It begins with two stanzas of a particular formal structure, namely two groups of four lines, followed and concluded by two other stanzas of three lines each, so that odd numbers follow even numbers, and between the two parts there is something like a rupture, which seems to signify and has often been used to signify something, so much so that the sonnet, however restricted, is a thought that unfolds, and is in that somehow akin to a syllogism, with its premises and conclusion. Of course it is perfectly possible to have a genuine poetic experience in a sonnet, just as much as in any other form. One may even experience in one's mind, at the transition from even numbers to odd ones in the ninth line, a sort of awakening to the sense of passing time, which is to say of existence, which is to say of the moment, which is a potential experience of the immediate. But it is no accident that the sonnet has for such a long time in its history been associated with the current of Platonism, for it is at least as much a discourse as a poem.Let us not dwell on those decidedly short forms that have been found in Western literature, such as the epigram. For in this case the aim is simply to highlight a brilliant idea, and we do not find ourselves in a relation to the reality outside ourselves, with nature, but within the margins of a

conversation, among talkers who are only interested in ideas and the beautiful language in which these ideas take form. Here, brevity is used to create surprise, to show off clever wit, but for this variety of brevity real poets can only feel repulsion, and rightly consider it futile, for in these cases they have not encountered an authentic short form.The unfortunate outcome of all this has been that poets who, in the nineteenth century, wrote short verses for no other purpose than to express a fleeting impression, have been themselves considered as worthless poets, or at least as minor poets, inferior to those who wrote much longer works. All the more so since the poets who were labeled minor, allowed themselves be persuaded that that indeed was what they seemed to be. A case in point is the poet Toulet, certainly not a great poet, yet in whose Contre-rimes sounds of great subtlety vibrate. Borges, who knew what poetry is about, had a

great admiration for Toulet, but in France he has not so far been accorded much importance. Almost the same thing could be said of Verlaine. In his case nobody would deny that he is indeed a great poet, yet most readings of his work reduce it to the reckless moments of his darkest days, instead of

recognizing that his poetry is capable of the greatest perceptiveness or even, as in Crimen Amoris, of posing, this time with great force, the problems of being-in-the-world in a most eloquent discourse. Speaking of Verlaine, I might observe in passing that, if I was asked to cite a few poems in French that are akin to haiku, I would immediately think of several of his. Is there not something recognizable to you in a fragment like:The shadow of trees on the surface of the foggy river

Fades like smoke,

While up in the air among the real boughs

Turtledoves coo plaintively.I have to add, however, that these lines by Verlaine do not in themselves constitute a poem, but are part of a longer text, and that if we are to find brevity in the history of French poetry, we have to plunge into long works, like a cormorant into a lake, to discover moments where the poet has briefly paused, raising his eyes from his discourse to look about him. In those instances brevity was for him an unforeseen happening, not something planned beforehand. Surely, however, this did not prevent him from feeling often that these were the very moments when his poetic project was at its best.

In the age of Romanticism, French society and religious belief had begun to change in a way that was favorable to the poetic understanding of reality. Together with a certain decline in the Christian conception of the world, the idea of a nature brimming with mysterious life stimulated poets to cling to the impressions they drew from it, so that the essentially poetic experience could assert itself against the more discursive elements in poems, and this created the conditions for a better understanding of the value and potential of poetic brevity, and even for making conscious use of

it, by considering that it could be the very heart of poetic exploration. That is precisely what happened in the case of Rimbaud, who started by writing long poems brimming with ideas, and who quite rapidly turned to the incandescent notations of his 1872 poems and his Illuminations. One can say that these poems of Rimbaud's are the first great creations of the short form in French, in the work of a poet whom one might compare, it seems to me, to certain poets of Japan on account of his way of life. While Rimbaud's poems offered a great model for the modern age, they remained

nonetheless an exception, and, for those among us in France who know better today than yesterday that the perception of the sentient world lies at the heart of poetry, more and other poetic testimonies were needed.That is why the interest in haiku spread in France in the second half of the twentieth century, and remains strong today. This interest took root when both texts and a certain idea about Japanese poets began to circulate, thanks to translations or commentaries, and that is how Blyth's book Haiku came to play a major role for some among us. In order to interest the French reader the translations did not need to preserve the richness of the original, because the simple fact of being concise, of being limited to a single glance, concentrating a few great realities of the natural or social world into one impression, had by now become something that people could understand as of specifically poetic value. And nothing, moreover, prevented the reader of these poems from studying their authors, taking cognizance of the Zen monks, and from imbuing themselves with a spirituality that answers powerfully to the spiritual needs of modern society, which has come to understand that many of its religious or metaphysical beliefs are mere myths. The idea that there is nothing behind the phenomena, that the human individual must not consider himself superior to nature: that is what we must henceforth accept, and what enables us to listen to the voice of haiku. I have no hesitation in saying that the best French poets since the fifties have given thought to this form of poetry. It is not a kind of "haiku fashion" that we have witnessed, but an awakening to a necessary and fundamental reference, which can only remain at the center of Western poetic thought.

IV

Now I must tell you what specific form this influence has assumed. It goes without saying that we do not need to imitate haiku, to write poems that are as short as possible, and correspond more or less to the number of words in a haiku when it is translated into French. A few poets have attempted this, in a naive way, but that is to be misled. Unlike Japanese, the French language does not have the visible aspect of signs to carry over the intuition of the poet, and the conceptual aspects of vocabulary continue to predominate in the words we use, even when their number is restricted, so that, if we are to reach the depth and limpidity of writing by the haiku masters, we will have to fight a long battle in our reliance on adjectives and nouns, and the signs of this struggle will have to be

sufficiently present in the poem for the reader to recognize it, relive it, and thus learn and observe how the poet managed to compose the poem. As it was in the past in French poetry, so it is still today, that brevity is a passing state that one occasionally happens to attain, but nothing more. The only thing that we can do is to move gradually towards this state, within texts that remain long, and which are in the end a record of our search, the arduous and never ending attempt to reach transparency in our relationship to ourselves and the world.Here I want to add that the French poet still has a strong sense of himself as an individual, despite the quality of evidence offered by the lessons in non-individuality, in self-detachment, that he encounters in a Japanese poetry deeply imbued with Buddhism. In the West, it is hard to forget the

teachings of Christianity, which used to claim that the human individual has a reality of his own and absolute value. For us, poetic sensibility remains absorbed in the reflection of the poet upon himself, and the great poems therefore remain caught in a kind of ambiguity, divided between the concern for individual destiny and a need to plunge into the depths of the natural and cosmic world, where this destiny no longer has any meaning. Representative of this ambiguity is the frequently admirable work of Pierre-Albert Jourdan, who died prematurely about ten years ago. Works such as l'Entree dans le jardin (Entry into the Garden), or les Sandales de paille (Straw Sandals) - in the latter title you will no doubt recognize an allusion to the life of wandering poet-priests in Japan - embody simultaneously the heritage of St. Francis of Assissi and of the great travelogues of Basho.But perhaps you expect a more personal testimony from me. I can tell you that this interest in the short verse, and especially in haiku, is something I have experienced myself. First, it was a way of reading the authors of our French past. I remember my emotion when, in a collection of mediaeval texts, I came across what was nothing more than a fragment, the only remainder of a manuscript that was lost forever, but for me that fragment embodied in a single stroke poetry as such. It was these simple words: "Helas, Olivier Bachelin". Just three words, and two out of the three constituting a single proper name, that of Olivier Bachelin. But what a flash of intensity in an utterance so short! On the one hand, one man called Olivier Bachelin, someone who has lived, perhaps has loved, who has

known pleasure and pain, but about whom nothing is known, yet who, precisely for this reason, may represent the condition of each and every one of us in its most fundamental meaning. And on the other hand, this "alas", which suggests that some misfortune had befallen him, which reminds us of the vicissitudes of life, of the risk inherent in it, and of the void that gapes beneath it, the two poles of our concern on earth, with this abrupt reconciliation between them that reveals the identity of being and of nothingness. Then one turns back upon the world a gaze freed of illusions, a gaze without recoil, a gaze which takes in everything which is, or rather which is not, with a silent immediacy. That "Helas, Olivier Bachelin", in its extreme laconism, embodied poetry for me in a much more direct and powerful way than many long poems, and I would be tempted to compare these words to a haiku if I were not aware that they are still haunted by that Western dream that the individual as such is an

absolute reality.That dream existed likewise in me, and when I began writing seriously myself, writing from the outset short, very short verses, the ones that make up the first part of my first book Du mouvement et de l'immobilite de Douve (On the movement and immobility of Douve), published in 1953, I was forced to admit that these texts too were burdened by that preoccupation with individual destiny, and this prevented them from genuinely encountering reality in its unity, and prompted me, in short, to embark upon a long work of inner clarification, where the ego that stubbornly clings to its illusions would be forced to disperse in the evidence of the world. Obviously an impossible task, or at any rate a never ending one, at least for me, but it opened up a path that I believe to be of specific relevance for modern poetry in the West, and it showed how from our own perspectives we may encounter haiku, encounter that teaching where poetry and wisdom are combined. That encounter will take place at moments whenever, in the midst of our writing, where the ego continues its soliloquy, we should succeed, because of something that happens in our lives, in seeing silent reality raise itself before us, a reality which is quite alien to our concerns and at the same time mysteriously hospitable.

One of these moments appears in the book I have already cited, at least that is how I understand it, and so it is for me the first thing I ever wrote that is sufficiently akin to haiku for me to allow myself to quote it. It consists simply of two lines, but in my view they constitute a whole poem, which I have presented separately from others, on a page by itself. It runs:Tu as pris une lampe et tu ouvres la porte.

Que faire d'une lampe, il pleut, le jour se lève.(You have taken a lamp and you open the door.

What use is a lamp, it's raining, the day breaks.)You will see what is at issue here: the discovery in the morning of the rain that veils the countryside, the ego which in that great silent manifestation suddenly detaches itself from the self, so that there is no longer any need for the lamp which would have served the pursuit of one of his ordinary activities, and a new light appears, or rather the light of every day appears in a new way. In that moment on the threshold of the house, perhaps after a tormented night, conciseness was necessary if I was to remain true to my experience. Adding anything to these few words would only have had the effect of making me forget the experience.

Since that time I have found myself very often far away from that clarity, from that quality of evidence, but at least I could no longer deny what poetry was, and this prepared me better than before for the reading of haiku, and so I was ready to appreciate Basho when, in the sixties, a French translation of The Narrow Road to the Interior was published. I still remember my excitement when I read the first lines of the book. "The months and days are eternal travellers ... In which year it was I do not recall, but, like a wisp of cloud borne upon the wind, I too have been carried away by wanderlust." With this translation of Basho, with the anthology of haiku compiled later by Roger Munier, it was the great Japanese poetry that took the stage in France. I have no doubt that it will continue to speak to our most intimate preoccupations. I even dare to think that there will be in French poetry a spate of experimentation with short verse forms which will be the direct result of haiku, of what they have of universal, of international value: not a precise form, but a spirit, an immense capacity for spiritual experience.

Thank you once again. I also owe it to the attention you have so graciously accorded me that I have become better acquainted with the work of the poets of Matsuyama, in particular Masaoka Shiki. It is desirable that these poets become better known in France, and I am happy that, thanks to you, I am in a position to talk about them in my country. It is also to be hoped that your project for an international reflection on haiku and short verse will develop particularly with the European nations, and I hope that I will be able to take back home from these days spent among you, precise programs

that will allow for new exchanges, for the greater good of poetry, which is our common good and one of the few means that remain for preserving society from the dangers that beset it.(translated from the French by W. F. Vande Walle with D. Burleigh)