Terebess

Asia Online (TAO)

Index

Home

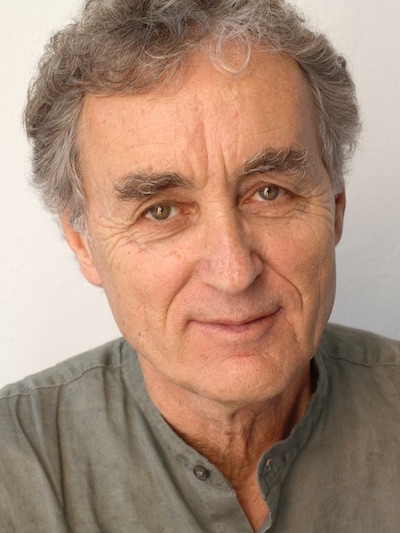

Fritjof Capra (1939-)

The immune system our second brain

Where

Have All the Flowers Gone?

Reflections on the Spirit and Legacy of the Sixties

The

Roots of Terrorism

Reflections on September 11, One Year Later

Trying

to Understand

A Systemic Analysis of International Terrorism

Is

It True That the Buddha Would Just Be a Physicist?

From

an Interview with Physicist Fritjof Capra

The

Tao of Physics (1975)

by Fritjof Capra

PREFACE

Five years ago, I had a beautiful experience which set me on a road that has led to the writing of this book. I was sitting by the ocean one late summer afternoon, watching the waves rolling in and feeling the rhythm of my breathing, when I suddenly became aware of my whole environment as being engaged in a gigantic cosmic dance. Being a physicist, I knew that the sand, rocks, water, and air around me were made of vibrating molecules and atoms, and that these consisted of particles which interacted with one another by creating and destroying other particles. I knew also that the earth's atmosphere was continually bombarded by showers of "cosmic rays," particles of high energy undergoing multiple collisions as they penetrated the air. All this was familiar to me from my research in high-energy physics, but until that moment I had only experienced it through graphs, diagrams, and mathematical theories. As I sat on that beach my former experiences came to life; I "saw" cascades of energy coming down from outer space, in which particles were created and destroyed in rhythmic pulses; I "saw" the atoms of the elements and those of my body participating in this cosmic dance of energy; I felt its rhythm and I "heard" its sound, and at that moment I knew that this was the Dance of Shiva, the Lord of Dancers worshiped by the Hindus. I had gone through a long training in theoretical physics and had done several years of research. At the same time, I had become very interested in Eastern mysticism and had begun to see the parallels to modern physics. I was particularly attracted to the puzzling aspects of Zen which reminded me of the puzzles in quantum theory. At first, however, relating the two was a purely intellectual exercise. To overcome the gap between rational, analytical thinking and the meditative experience of mystical truth, was, and still is, very difficult for me. In the beginning, I was helped on my way by "power plants" which showed me how the mind can flow freely; how spiritual insights come on their own, without any effort, emerging from the depth of consciousness. I remember the first such experience. Coming, as it did, after years of detailed analytical thinking, it was so overwhelming that I burst into tears, at the same time, not unlike Castaneda, pouring out my impressions on to a piece of paper. Later came the experience of the Dance of Shiva which I have tried to capture in the photomontage shown in Plate 7. It was followed by many similar experiences which helped me gradually to realize that a consistent view of the world is beginning to emerge from modern physics which is harmonious with ancient Eastern wisdom. I took many notes over the years, and I wrote a few articles about the parallels I kept discovering, until I finally summarized my experiences in the present book. This book is intended for the general reader with an interest in Eastern mysticism who need not necessarily know anything about physics. I have tried to present the main concepts and theories of modern physics without any mathematics and in non-technical language, although a few paragraphs may still appear difficult to the layperson at first reading. The technical terms I had to introduce are all defined where they appear for the first time and are listed in the index at the end of the book. I also hope to find among my readers many physicists. with an interest in the philosophical aspects of physics, I who have as yet not come in contact with the religious philosophies of the East. They will find that Eastern mysticism provides a consistent and beautiful philosophical framework which can accommodate our most advanced theories of the physical world. As far as the contents of the book are concerned, the reader may feel a certain lack of balance between the presentation of scientific and mystical thought. Throughout the book, his or her understanding of physics should progress steadily, but a comparable progression in the understanding of Eastern mysticism may not occur. This seems unavoidable, as mysticism is, above all, an experience that cannot be learned from books. A deeper understanding of any mystical tradition can only be felt when one decides to become actively involved in it. All I can hope to do is to generate the feeling that such an involvement would be highly rewarding. During the writing of this book, my own understanding of Eastern thought has deepened considerably. For this I am indebted to two men who come from the East. I am profoundly grateful to Phiroz Mehta for opening my eyes to many aspects of Indian mysticism, and to my T'ai Chi master Liu Hsiu Ch'i for introducing me to living Taoism. It is impossible to mention the names of everyone- scientists, artists, students, and friends-who have helped me formulate my ideas in stimulating discussions. I feel, however, that I owe special thanks to Graham Alexander Jonathan Ashmore, Stratford Caldecott, Lyn Gambles Sonia Newby, Ray Rivers, Joel Scherk, George Sudarshan and -last but not least- Ryan Thomas. Finally, I am indebted to Mrs. Pauly Bauer-Ynnhof of Vienna for her generous financial support at a time when it was needed most.Fritjof Capra

December 1974ON CHINESE THOUGHT

When Buddhism arrived in China, around the first century A.D., it encountered a culture which was more than two thousand years old. In this ancient culture, philosophical thought had reached its culmination during the late Chou period (c. 500-221 B.C.), the golden age of Chinese philosophy, and from then on had always been held in the highest esteem.

From the beginning, this philosophy had two complementary aspects. The Chinese being practical people with a highly developed social consciousness, all their philosophical schools were concerned, in one way or the other, with life in society, with human relations, moral values and government. This, however, is only one aspect of Chinese thought. Complementary to it is that corresponding to the mystical side of the Chinese character, which demanded that the highest aim of philosophy should be to transcend the world of society and everyday life and to reach a higher plane of consciousness. This is the plane of the sage, the Chinese ideal of the enlightened man who has achieved mystical union with the universe. The Chinese sage, however, does not dwell exclusively on this high spiritual plane, but is equally concerned with worldly affairs. He unifies in himself the two complementary sides of human nature -intuitive wisdom and practical knowledge, contemplation and social action- which the Chinese have associated with the images of the sage and of the king. Fully realized human beings, in the words of Chuang Tzu, "by their stillness become sages, by their movement kings."

During the sixth century B.C., the two sides of Chinese philosophy developed into two distinct philosophical schools, Confucianism and Taoism. Confucianism was the philosophy of social organization, of common sense and practical knowledge. It provided Chinese society with a system of education and with strict conventions of social etiquette. One of its main purposes was to form an ethical basis for the traditional Chinese family system with its complex structure and its rituals of ancestor worship. Taoism, on the other hand, was concerned primarily with the observation of nature and the discovery of its Way, or Tao. Human happiness, according to the Taoists, is achieved when men follow the natural order, acting spontaneously and trusting their intuitive knowledge.

These two trends of thought represent opposite poles in Chinese philosophy, but in China they were always seen as poles of one and the same human nature, and thus as complementary. Confucianism was generally emphasized in the education of children who had to learn the rules and conventions necessary for life in society, whereas Taoism used to be pursued by older people in order to regain and develop the original spontaneity which had been destroyed by social conventions. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the Neo-Confucian school attempted a synthesis of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism, which culminated in the philosophy of Chu Hsi, one of the greatest of all Chinese thinkers. Chu Hsi was an outstanding philosopher who combined Confucian scholarship with a deep understanding of Buddhism and Taoism, and incorporated elements of all three traditions in his philosophical synthesis.

Confucianism derives its name from Kung Fu Tzu, or Confucius, a highly influential teacher with a large number of students who saw his main function as transmitting the ancient cultural heritage to his disciples. In doing so, however, he went beyond a simple transmission of knowledge for he interpreted the traditional ideas according to his own moral concepts. His teachings were based on the so-called Six Classics, ancient books I of philosophical thought, rituals, poetry, music, and history, which represented the spiritual and cultural heritage of the "holy sages" of China's past. Chinese tradition has associated Confucius with all of these works either as author, commentator, or editor; but according to modern scholarship he was neither the author, commentator, nor even the editor of any of the Classics. Hi own ideas became known through the Lun Yu, or Confucian Analects, a collection of aphorisms which wa compiled by some of his disciples.

The originator of Taoism was Lao Tzu, whose name literally means "The Old Master" and who was, according to tradition, an older contemporary of Confucius. He is said to have been the author of a short book of aphorisms which is considered as the main Taoist scripture. In China, it is generally just called the Lao-tzu, and in the West it is usually known as the Tao Te Ching, the Classic of the Way and Power, a name which was given to it in later times. I have already mentioned the paradoxical style and the powerful and poetic language of this book which Joseph Needham considers to be "without exception the most profound and beautiful work in the Chinese language."

The second important Taoist book is the Chuang-tzu a much larger book than the Tao Te Tjing, whose author, Chuang Tzu, is said to have lived about two hundred years after Lao Tzu. According to modern scholarship, however, the Chuang-tzu, and probably also the Lao-tzu, cannot be seen as the work of a single author, but rather constitute a collection of Taoist writing compiled by different authors at different times.

Both the Confucian Analects and the Tao Te Tjing are written in the compact suggestive style which is typical of the Chinese way of thinking. The Chinese mind was not given to abstract logical thinking and developed a language which is very different from that which evolved in the West. Many of its words could be used as nouns adjectives, or verbs, and their sequence was determined not so much by grammatical rules as by the emotional content of the sentence. The classical Chinese word was very different from an abstract sign representing a clearly delineated concept. It was rather a sound symbol which had strong suggestive powers, bringing to mind an indeterminate complex of pictorial images and emotions. The intention of the speaker was not so much to express an intellectual idea, but rather to affect and influence the listener. Correspondingly, the written character was not just an abstract sign, but was an organic pattern -a "gestalt"- which preserved the full complex of images and the suggestive power of the word.

Since the Chinese philosophers expressed themselves in a language which was so well suited for their way of thinking, their writings and sayings could be short and inarticulate, and yet rich in suggestive images. It is clear that much of this imagery must be lost in an English translation. A translation of a sentence from the Tao Te Ching, for example, can only render a small part of the rich complex of ideas contained in the original, which is why different translations from this controversial book often look like totally different texts. As Fung Yu-Lan has said, "It needs a combination of all the translations already made and many others not yet made, to reveal the richness of the Lao-tzu and the Confucian Analects in their original form."

The Chinese, like the Indians, believed that there is an ultimate reality which underlies and unifies the multiple things and events we observe:There are the three terms -"complete," "all-embracing," "the whole." These names are different, but the reality sought in them is the same: referring to the One thing. They called this reality the Tao, which originally meant 'the Way.' It is the way, or process, of the universe, the order of nature. In later times, the Confucianists gave it a different interpretation. They talked about the Tao of man, or the Tao of human society, and understood it as the right way of life in a moral sense.

In its original cosmic sense, the Tao is the ultimate, undefinable reality and as such it is the equivalent of the Hinduist Brahman and the Buddhist Dharmakaya. It differs from these Indian concepts, however, by its intrinsically dynamic quality which, in the Chinese view, is the essence of the universe. The Tao is the cosmic process in which all things are involved; the world is seen a continuous flow and change.

Indian Buddhism, with its doctrine of impermanence, had quite a similar view, but it took this view merely the basic premise of the human situation and went to elaborate its psychological consequences. The Chinese on the other hand, not only believed that flow and change were the essential features of nature, but also that there are constant patterns in these changes, to be observed by man. The sage recognizes these patterns and directs his actions according to them. In this way he becomes 'one with the Tao,' living in harmony with nature and succeeding in everything he undertakes. In the words of Huai Nan Tzu, a philosopher of the second century B.C.:He who conforms to the course of the Tao,

following the natural processes of Heaven and Earth,

find it easy to manage the whole world.What, then, are the patterns of the cosmic Way which man has to recognize? The principal characteristic of Tao is the cyclic nature of its ceaseless motion change. "Returning is the motion of the Tao," says Tzu, and "Going far means returning." The idea is all developments in nature, those in the physical world as well as those of human situations, show cyclic pattern of coming and going, of expansion and contraction.

This idea was no doubt deduced from the movement of the sun and moon and from the change of seasons, but it was then also taken as a rule of life. Chinese believe that whenever a situation develops its extreme, it is bound to turn around and become opposite. This basic belief has given them courage and perseverance in times of distress and has made them cautious and modest in times of success. It has led to the doctrine of the golden mean in which both Taoists and Confucianists believe. "The sage," says Lao Tzu, "avoids excess, extravagance, and indulgence."

In the Chinese view, it is better to have too little than to have too much, and better to leave things undone than to overdo them, because although one may not get very far this way, one is certain to go in the right direction. Just as the man who wants to go farther and farther East will end up in the West, those who accumulate more and more money in order to increase their wealth will end up being poor. Modern industrial society which is continuously trying to increase the "standard of living" and thereby decreases the quality of life for all its members is an eloquent illustration of this ancient Chinese wisdom.

The idea of cyclic patterns in the motion of the Tao was given a definite structure by the introduction of the polar opposites yin and yang. They are the two poles which set the limits for the cycles of change:The yang having reached its climax retreats

in favor of the yin; the yin having reached

its climax retreats in favor of the yang.In the Chinese view, all manifestations of the Tao are generated by the dynamic interplay of these two polar forces. This idea is very old and many generations worked on the symbolism of the archetypal pair yin and yang until it became the fundamental concept of Chinese thought. The original meaning of the words yin and yang was that of the shady and sunny sides of a mountain, a meaning which gives a good idea of the relativity of the two concepts:

That which lets now the dark, now the light appear is Tao.

From the very early times, the two archetypal poles of nature were represented not only by bright and dark, but also by male and female, firm and yielding, above and below. Yang, the strong, male, creative power, was associated with Heaven, whereas yin, the dark, receptive, female and maternal element, was represented by the Earth. Heaven is above and full of movement, the Earth -in the old geocentric view- is below and resting, and thus yang came to symbolize movement and yin rest. In the realm of thought, yin is the complex, female, intuitive mind, yang the clear and rational male intellect. Yin is the quiet, contemplative stillness of the sage, yang the strong, creative action of the king.

The dynamic character of yin and yang is illustrated by the ancient Chinese symbol called Fai-ch; T'u, 'Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate': This diagram is a symmetric arrangement of the dark yin and the bright yang, but the symmetry is not static. It is a rotational symmetry suggesting, very forcefully, continuous cyclic movement:The yang returns cyclically to its beginning; the yin

attains its maximum and gives place to the yang.The two dots in the diagram symbolize the idea that each time one of the two forces reaches its extreme, it contains in itself already the seed of its opposite.

The pair of yin and yang is the grand leitmotiv that permeates Chinese culture and determines all features of the traditional Chinese way of life. "Life," says Chua Tzu, "is the blended harmony of the yin and yang." As a nation of farmers, the Chinese had always been familiar with the movements of the sun and moon and with the change of the seasons. Seasonal changes and the resulting phenomena of growth and decay in organic nature we thus seen by them as the clearest expressions of the interplay between yin and yang, between the cold a dark winter and the bright and hot summer. The seasonal interplay of the two opposites is also reflect in the food we eat which contains elements of yin and yang. A healthy diet consists, for the Chinese, in balancing these yin and yang elements.

Traditional Chinese medicine, too, is based on the balance of yin and yang in the human body, and a illness is seen as a disruption of this balance. The body is divided into yin and yang parts. Globally speaking, the inside of the body is yang, the body surface is yin; the back is yang, the front is yin; inside the body, there are yin and yang organs. The balance between all these parts is maintained by a continuous flow of ch'i, or vital energy, along a system of "meridians" which contain the acupuncture points. Each organ has a meridian associated with it in such a way that yang meridians belong to yin organs and vice versa. Whenever the flow between the yin and yang is blocked, the body falls ill, and the illness is cured by sticking needles into the acupuncture points to stimulate and restore the flow of ch'i.

The interplay of yin and yang, the primordial pair of opposites, appears thus as the principle that guides all the movements of the Tao, but the Chinese did not stop there. They went on to study various combinations of yin and yang which they developed into - a system of cosmic archetypes. This system is elaborated in the I Ching, or Book of Changes.

The Book of Changes is the first among the six Confucian Classics and must be considered as a work which lies at the very heart of Chinese thought and culture. The authority and esteem it has enjoyed in China throughout thousands of years is comparable only to those of sacred scriptures, like the Vedas or the Bible, in other cultures. The noted sinologue Richard Wilhelm begins the introduction to his translation of the book with the following words:The Book of Changes -I Ching in Chinese- is unquestionably one of the most important books in the world's literature. Its origin goes back to mythical antiquity, and it has occupied the attention of the most eminent scholars of China down to the present day. Nearly all that is greatest and most significant in the three thousand years of Chinese cultural history has either taken its inspiration from this book, or has exerted an influence on the interpretation of its text. Therefore it may safely be said that the seasoned wisdom of thousands of years has gone into the making of the I Ching.

The Book of Changes is thus a work that has grown organically over thousands of years and consists of many layers stemming from the most important periods Chinese thought.

The use of the I Ching as a book of wisdom is, in fact, of far greater importance than its use as an oracle. It has inspired the leading minds of China throughout the ages, among them Lao Tzu, who drew some of his profoundest aphorisms from this source. Confucius studied it intensively and most of the commentaries on the text which make up the later strata of the book go back to his school. These commentaries, the so-called Ten Wings, combine the structural interpretation of the hexagrams with philosophical explanations.

At the center of the Confucian commentaries, as of the entire I Ching, is the emphasis on the dynamic aspect of all phenomena. The ceaseless transformation of all things and situations is the essential message of the Book of Changes:The Changes is a book

From which one may not hold aloof.

Its tao is forever changing-

Alteration, movement without rest,

Flowing through the six empty places,

Rising and sinking without fixed law,

Firm and yielding transform each other.

They cannot be confined within a rule,

It is only change that is at work here.ZEN

When the Chinese mind came in contact with Indian thought in the form of Buddhism, around the first century A.D., two parallel developments took place. On the one hand, the translation of the Buddhist sutras stimulated Chinese thinkers and led them to interpret the teachings of the Indian Buddha in the light of their own philosophies. Thus arose an immensely fruitful exchange of ideas which culminated in the Hua-yen (Sanskrit: Avatamsaka) school of Buddhism in China and in the Kegon school in Japan.On the other hand, the pragmatic side of the Chinese mentality responded to the impact of Indian Buddhism by concentrating on its practical aspects and developing them into a special kind of spiritual discipline which was given the name Ch'an, a word usually translated as "meditation." This Ch'an philosophy was eventually adopted by Japan, around A.D. 1200, and has been cultivated there, under the name of Zen, as a living tradition up to the present day. Zen is thus a unique blend of the philosophies and idiosyncrasies of three different cultures. It is a way of life which is typically Japanese, and yet it reflects the mysticism of India, the Taoists' love of naturalness and spontaneity and the thorough pragmatism of the Confucian mind. In spite of its rather special character, Zen is purely Buddhistic in its essence because its aim is no other than that of the Buddha himself: the attainment of enlightenment, an experience known in Zen as satori. The enlightenment experience is the essence of all schools of Eastern philosophy, but Zen is unique in that it concentrates exclusively on this experience and is not interested in any further interpretations. In the words of Suzuki, "Zen is discipline in enlightenment." From the standpoint of Zen, the awakening of the Buddha and the Buddha's teaching that everybody has the potential of attaining this awakening are the essence of Buddhism. The rest of the doctrine, as expounded in the voluminous sutras, is seen as supplementary. The experience of Zen is thus the experience of satori, and since this experience, ultimately, transcends all categories of thought, Zen is not interested in any abstraction or conceptualization. It has no special doctrine or philosophy, no formal creeds or dogmas, and it asserts that this freedom from all fixed beliefs makes it truly spiritual. More than any other school of Eastern mysticism, Zen is convinced that words can never express the ultimate truth. it must have inherited this conviction from Taoism, which showed the same uncompromising attitude. "If one asks about the Tao and another answers him," said Chuang Tzu, "neither of them knows it."' Yet the Zen experience can be passed on from teacher to pupil, and it has, in fact, been transmitted for many centuries by special methods proper to Zen. In a classic summary of four lines, Zen is described as:

A special transmission outside the scriptures,

Not founded upon words and letters,

Pointing directly to the human mind,

Seeing into one's nature and attaining Buddhahood.This technique of "direct pointing" constitutes the special flavor of Zen. It is typical of the Japanese mind which is more intuitive than intellectual and likes to give out facts as facts without much comment. The Zen masters were not given to verbosity and despised all theorizing and speculation. Thus they developed methods of pointing directly to the truth, with sudden and spontaneous actions or words, which expose the paradoxes of conceptual thinking and, like the koans I have already mentioned, are meant to stop the thought process to make the student ready for the mystical experience. This technique is well illustrated by the following examples of short conversations between master and disciple. In these conversations, which make up most of the Zen literature, the masters talk as little as possible and use their words to shift the disciples' attention from abstract thoughts to the concrete reality.

A monk, asking for instruction, said to Bodhidharma:

"I have no peace of mind. Please pacify my mind."

"Bring your mind here before me," replied Bodhidharma, "and I will pacify it!"

"But when I seek my own mind," said the monk, "I cannot find it."

"There!" snapped Bodhidharma, "I have pacified your mind!"A monk told Joshu: "I have just entered the monastery. Please teach me."

Joshu asked: "Have you eaten your rice porridge?"

The monk replied: "I have eaten"

Joshu said "Then you had better wash your bowl"These dialogues bring out another aspect which is characteristic of Zen. Enlightenment in Zen does not mean withdrawal from the world but means, on the contrary, active participation in everyday affairs. This viewpoint appealed very much to the Chinese mentality which attached great importance to a practical, productive life and to the idea of family perpetuation, and could not accept the monastic character of Indian Buddhism. The Chinese masters always stressed that Ch'an, or Zen, is our daily experience, the 'everyday mind' as Ma-tsu proclaimed. Their emphasis was on awakening in the midst of everyday affairs and they made it clear that they saw everyday life not only as the way to enlightenment but as enlightenment itself. In Zen, satori means the immediate experience of the Buddha nature of all things first and foremost among these things are the objects, affairs and people involved in everyday life, so that while it emphasizes life's practicalities, Zen is nevertheless profoundly mystical. Living entirely in the present and giving full attention to everyday affairs, one who has attained satori, experiences the wonder and mystery of life in every single act.

How wondrous this, how mysterious!

I carry fuel, I draw water.The perfection of Zen is thus to live one's everyday life naturally and spontaneously. When Po-chang was asked to define Zen, he said, "When hungry, eat, when tired, sleep." Although this sounds simple and obvious, like so much in Zen, it is in fact quite a difficult task. To regain the naturalness of our original nature requires long training and constitutes a great spiritual achievement. In the words of a famous Zen saying,

Before you study Zen,

mountains are mountains and rivers are rivers;

while you are studying Zen,

mountains are no longer mountains and rivers are no longer rivers;

but once you have had enlightenment

mountains are once again mountains and rivers again rivers.Zen's emphasis on naturalness and spontaneity certainly shows it Taoist roots but the basis for this emphasis is strictly Buddhistic. It is the belief in the perfection of our original nature, the realization that the process of enlightenment consists merely in becoming what we already are from the beginning. When the Zen master Po-chang was asked about seeking for the Buddha nature, he answered, "It's much like riding an ox in search of the ox." There are two principal schools of Zen in Japan today which differ in their methods of teaching. The Rinzai or 'sudden' school uses the koan method, and gives emphasis to periodic interviews with the master, called sanzen, during which the student is asked to present his view of the koan he is trying to solve. The solving of a koan involves long periods of intense concentration leading up to the sudden insight of satori. An experienced master knows when the student has reached the verge of sudden enlightenment and is able to shock him or her into the satori experience with unexpected acts such as a blow with a stick or a loud yell. The Soto or 'gradual school' avoids the shock methods of Rinzai and aims at the gradual maturing of the Zen student, "like the spring breeze which caresses the flower helping it to bloom". It advocates 'quiet sitting' and the use of one's ordinary work as two forms of meditation. Both the Soto and Rinzai schools attach the greatest importance to zazen, or sitting meditation, which is practiced in the Zen monasteries every day for many hours. The correct posture and breathing involved in this form of meditation is the first thing every student of Zen has to learn In Rinzai Zen, zazen is used to prepare the intuitive mind for the handling of the koan, and the Soto school considers it as the most important means to help the student mature and evolve towards satori. More than that it is seen as the actual realization of one's Buddha nature; body and mind being fused into a harmonious unity which needs no further improvement. As a Zen poem says,

Sitting quietly, doing nothing,

Spring comes, and the grass grows by itself.Since Zen asserts that enlightenment manifests itself in everyday affairs, it has had an enormous influence on all aspects of the traditional Japanese way of life. These include not only the arts of painting, calligraphy, garden design, etc., and the various crafts, but also ceremonial activities like serving tea or arranging flowers, and the martial arts of archery, swordsmanship, and judo [and many other do Martial Arts]. Each of these activities is known in Japan as a do, that is, a tao or 'way' toward enlightenment. They all explore various characteristics of the Zen experience and can be used to train the mind and to bring it in contact with the ultimate reality. I have already mentioned the slow, ritualistic activities of cha-no-yu, the Japanese tea ceremony, the spontaneous movement of the hand required for calligraphy and painting, and the spirituality of bushido, the "way of the warrior". All these arts are expressions of the spontaneity, simplicity and total presence of mind characteristic of the Zen life. While they all require a perfection of technique, real mastery is only achieved when technique is transcended and the art becomes an "artless art" growing out of the unconscious. We are fortunate to have a wonderful description of such an "artless art" in Eugen Herrigel's little book Zen in the Art of Archery. Herrigel spent more than five years with a celebrated Japanese master to learn his "mystical" art, and he gives us in his book a personal account of how he experienced Zen through archery. He describes how archery was presented to him as a religious ritual which is "danced" in spontaneous, effortless and purposeless movements. It took him many years of hard practice, which transformed his entire being, to learn how to draw the bow "spiritually," with a kind of effortless strength, and to release the string "without intention," letting the shot "fall from the archer like a ripe fruit." When he reached the height of perfection, bow, arrow, goal, and archer all melted into one another and he did not shoot, but "it" did it for him. Herrigel's description of archery is one of the purest accounts of Zen because it does not talk about Zen at all. TAOISM

Mistrust of conventional knowledge and reasoning is stronger in Taoism than in any other school of Eastern philosophy. It is based on the firm belief that the human intellect can never comprehend the Tao. In the words of Chuang Tzu,The most extensive knowledge does not necessarily know it;

reasoning will not make men wise in it.

The sages have decided against both these methods.Chuang Tzu's book is full of passages reflecting the Taoist's contempt of reasoning and argumentation. Thus he says

A dog is not reckoned good because he barks well,

and a man is not reckoned wise because he speaks skillfully.and

Disputation is a proof of not seeing clearly.

Logical reasoning was considered by the Taoists as part of the artificial world of man, together with social etiquette and moral standards. They were not interested in this world at all, but concentrated their attention fully on the observation of nature in order to discern the characteristics of the Tao. Thus they developed an attitude which was essentially scientific and only their deep mistrust in the analytic method prevented them from constructing proper scientific theories. Nevertheless, the careful observation of nature, combined with a strong mystical intuition, led the Taoist sages-to profound insights which are confirmed by modern scientific theories.One of the most important insights of the Taoists was the realization that transformation and change are essential features of nature. A passage in the Chuang-tzu shows clearly how the fundamental importance of change was discerned by observing the organic world

In the transformation and growth of all things, every bud and feature has its proper form. In this we have their gradual maturing and decay, the constant flow of transformation and change

The Taoists saw all changes in nature as manifestations of the dynamic interplay between the polar opposites yin and yang, and thus they came to believe that any pair of opposites constitutes a polar relationship where each of the two poles is dynamically linked to the other. For the Western mind, this idea of the implicit unity of all opposites is extremely difficult to accept. It seems most paradoxical to us that experiences and values which we had always believed to be contrary should be, after all, aspects of the same thing. In the East, however, it has always been considered as essential for attaining enlightenment to go 'beyond earthly opposites,' and in China the polar relationship of all opposites lies at the very basis of Taoist thought. Thus Chuang Tzu says

The "this" is also "that." The "that" is also "this." . . .

That the "that" and the "this" cease to be opposites

is the very essence of Tao.

Only this essence, an axis as it were,

is the center of the circle

responding to the endless changesFrom the notion that the movements of the Tao are a continuous interplay between opposites, the Taoists deduced two basic rules for human conduct. Whenever you want to achieve anything, they said, you should start with its opposite. Thus Lao Tzu

In order to contract a thing, one should surely expand it first.

In order to weaken, one will surely strengthen first.

In order to overthrow, one will surely exalt first.

"In order to take, one will surely give first."

This is called subtle wisdom.On the other hand, whenever you want to retain anything, you should admit in it something of its opposite:

Be bent, and you will remain straight.

Be vacant, and you will remain full.

Be worn, and you will remain new.This is the way of life of the sage who has reached a higher point of view, a perspective from which the relativity and polar relationship of all opposites are clearly perceived. These opposites include, first and foremost, the concepts of good and bad which are interrelated in the same way as yin and yang. Recognizing the relativity of good and bad, and thus of all moral standards, the Taoist sage does not strive for the good but rather tries to maintain a dynamic balance between good and bad. Chuang Tzu is very clear on this point

The sayings, "Shall we not follow and honor the right

and have nothing to do with the wrong?" and

"Shall we not follow and honor those who secure good government

and have nothing to do with those who produce disorder?"

show a want of acquaintance with the principles of Heaven and Earth

and with the different qualities of things.

It is like following and honoring Heaven and taking no account of Earth;

it is like following and honoring the yin and taking no account of the yang.

It is clear that such a course cannot be pursued.It is amazing that, at the same time when Lao Tzu and his followers developed their world view, the essential features of this Taoist view were taught also in Greece, by a man whose teachings are known to us only in fragments and who was, and still is, very often misunderstood. This Greek "Taoist" was Heraclitus of Ephesus. He shared with Lao Tzu not only the emphasis on continuous change, which he expressed in his famous saying "Everything flows," but also the notion that all changes are cyclic. He compared the world order to "an ever-living fire, kindling in measures and going out in measures," an image which is indeed very similar to the Chinese idea of the Tao manifesting itself in the cyclic interplay of yin and yangIt is easy to see how the concept of change as a dynamic interplay of opposites led Heraclitus, like Lao Tzu, to the discovery that all opposites are polar and thus united. "The way up and down is one and the same," said the Greek, and "God is day night, winter summer, war peace, satiety hunger." Like the Taoists, he saw any pair of opposites as a unity and was well aware of the relativity of all such concepts. Again the words of Heraclitus -"Cold things warm themselves, warm cools, moist dries, parched is made wet" remind us strongly of those of Lao Tzu, "Easy gives rise to difficult...resonance harmonizes sound, after follows beforeIt is surprising that the great similarity between the world views of those two sages of the sixth century B.C. is not generally known. Heraclitus is often mentioned in connection with modern physics, but hardly ever in connection with Taoism. And yet it is this connection which shows best that his world view was that of a mystic and thus, in my opinion, puts the parallels between his ideas and those of modern physics in the right perspective. When we talk about the Taoist concept of change, it is important to realize that this change is not seen as occurring as a consequence of some force, but rather as a tendency which is innate in all things and situations. The movements of the Tao are not forced upon it, but occur naturally and spontaneously. Spontaneity is the Tao's principle of action, and since human conduct should be modeled on the operation of the Tao, spontaneity should also be characteristic of all human actions. Acting in harmony with nature thus means for the Taoists acting spontaneously and according to one's true nature. It means trusting one's intuitive intelligence, which is innate in the human mind just as the laws of change are innate in all things around us. The actions of the Taoist sage thus arise out of his intuitive wisdom, spontaneously and in harmony with his environment. He does not need to force himself, or anything around him, but merely adapts his actions to the movements of the Tao. In the words of Huai Nan Tzu,

Those who follow the natural order flow in the current of the Tao.

Such a way of acting is called wu-wei in Taoist philosophy; a term which means literally "non-action," and which Joseph Needham translates as "refraining from activity contrary to nature," justifying this interpretation with a quotation from the Chuang-tzu:

Non-action does not mean doing nothing and keeping silent.

Let everything be allowed to do what it

naturally does, so that its nature will be satisfied.If one refrains from acting contrary to nature or, as Needham says, from "going against the grain of things," one is in harmony with the Tao and thus one's actions will be successful. This is the meaning of Lao Tzu's seemingly so puzzling words, "By non-action everything can be done." The contrast of yin and yang is not only the basic ordering principle throughout Chinese culture, but is also reflected in the two dominant trends of Chinese thought. Confucianism was rational, masculine, active and dominating. Taoism, on the other hand, emphasized all that was intuitive, feminine, mystical, and yielding. "Not knowing that one knows is best," says Lao Tzu, and "The sage carries on his business without action and gives his teachings without words." The Taoists believed that by displaying the feminine, yielding qualities of human nature, it was easiest to lead a perfectly balanced life in harmony with the Tao. Their ideal is best summed up in a passage from the Chuang-tzu which describes a kind of Taoist paradise: The men of old, while the chaotic condition was yet undeveloped, shared the placid tranquility which belonged to the whole world. At that time the yin and yang were harmonious and still; their resting and movement proceeded without any disturbance; the four seasons had their definite times; not a single thing received any injury, and no living being came to a premature end. Men might be possessed of the faculty of knowledge, but they had no occasion for its use. This was what is called the state of perfect unity. At this time, there was no action on the part of anyone but a constant manifestation of spontaneity.