ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

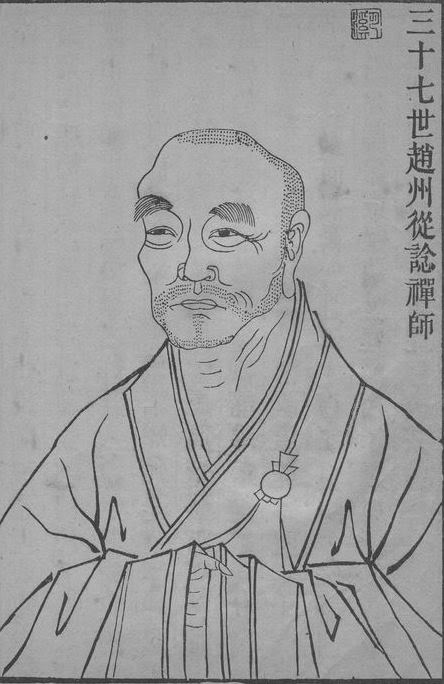

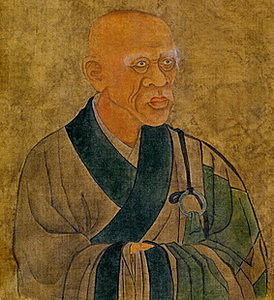

趙州從諗 Zhaozhou Congshen (778–897)

趙州錄 Zhaozhou lu

(Rōmaji:) Jōshū Jūshin: 赵州录 Jōshū-roku

(English:) The Recorded Sayings of Zhaozhou

(Magyar:) Csao-csou Cung-sen: Csao-csou lu / Feljegyzések Csao-csouról

Tartalom |

Contents |

Csao-csou összegyűjtött mondásaiból Zhaozhou Congshen: A tizenkét óra dala |

PDF: Radical Zen: The sayings of Joshu PDF: The Recorded Sayings of Zen Master Joshu Ts'ung-shen of Chao-chou (778-897?) Encounter Dialogues of Zhaozhou Congshen PDF: Old Joshu Lives On |

Csao-csou Cung-sen összegyűjtött mondásaiból

Fordította: Terebess Gábor

A Kőrösi Csoma Sándor Intézet Közleményei, 1977. 1-2. szám, 62-71. oldal

Vö.: Folyik a híd, Officina Nova, Budapest, 1990, 40-53. oldal

Cung-sen csan mester egy caocsoui Ho család sarja volt. Szinte még gyerekfejjel lépett a szülővárosabeli Hutung-kolostorba. Tizennyolc éves korában Nan-csüan mester tanítványának szegődött Csicsouba. Miután megvilágosodott, a Szung-hegyre ment, hogy szerzetessé avassák, majd visszatért Nan-csüanhoz. Csak a mester halála után, majd hatvan évesen indult vándorútra, és kora valamennyi ismert csan mesterét végiglátogatta. „Egy hétéves gyerektől se restellek tanulni, ha többet tud nálam – mondotta –, de egy százéves embert se restellek oktatni, ha kevesebbet tud nálam." Csao-csou nem tanított se bottal, se ordítással, mint a kortárs csan mesterek, de „fény sugárzott az ajkáról".

80 éves korában elfogadta a Kuanjin-kolostor vezetését Csaocsouban; e helység után ismert Csao-csou néven. Haláláig a kolostor feje maradt, s bár birodalomszerte híres csan mesternek számított, s rajzottak körötte nevesebbnél nevesebb tanítványok, szerénységét megőrizte. Negyven év alatt egy alamizsna-kérő levelet sem írt, egy új bútordarabot se csináltatott, legfeljebb csak toldozni-foldozni volt hajlandó. Halála előtt – 120 éves korában – elküldte légyhessegetőjét a tartományi kormányzónak: „Egész életemben használtam – üzente –, de elhasználni nem tudtam."

Posztumusz címként a Csen-csi (=Végső Igazság) csan mester nevet kapta.

– Mi az Út? – kérdezte Csao-csou.

– A mindennapi gondolkodás – válaszolta Nan-csüan.

– Hogyan térhetünk rá?

– Ha tudatosan akarsz rátérni, máris tévúton jársz.

– De akkor hogy tudhatok róla?

– Az Útnak nincs köze se tudáshoz, se nemtudáshoz – mondotta Nan-csüan. – A tudás káprázat, a nemtudás zűrzavar. Ha valóban tudatosság nélkül éred el az Utat, mintha mérhetetlen ürességbe jutnál, nem lesz előtted se akadály, se határ. Hogy lehetne akkor állítani vagy tagadni?Egyszer a Nyugati és a Keleti Csarnok szerzetesei veszekedtek egy kismacskán. Nan-csüan mester felvette a macskát és elibük tartotta:

– Szóljatok érte egy szót, vagy megölöm!

A szerzetesek zavartan hallgattak, mire Nan-csüan kettévágta a macskát.

Estefelé megérkezett Csao-csou, és Nan-csüan elmesélte neki, mi történt. Csao-csou levette egyik szalmabocskorát, a feje tetejére rakta és indult kifelé.

– Ha itt lettél volna – sóhajtott Nan-csüan –, megmented azt a macskát.

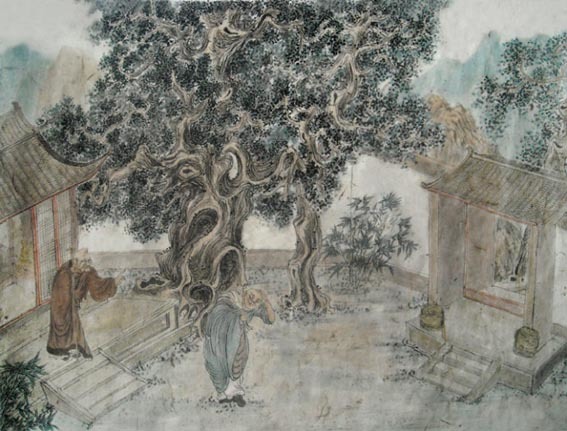

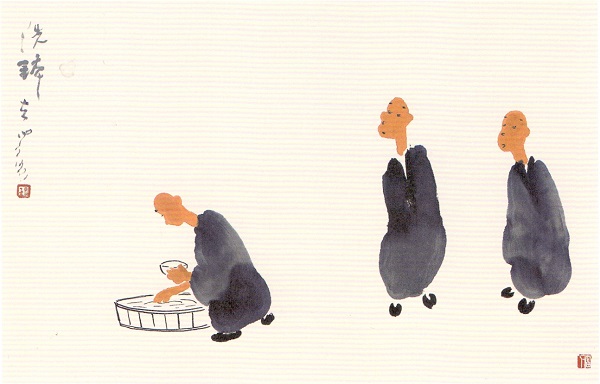

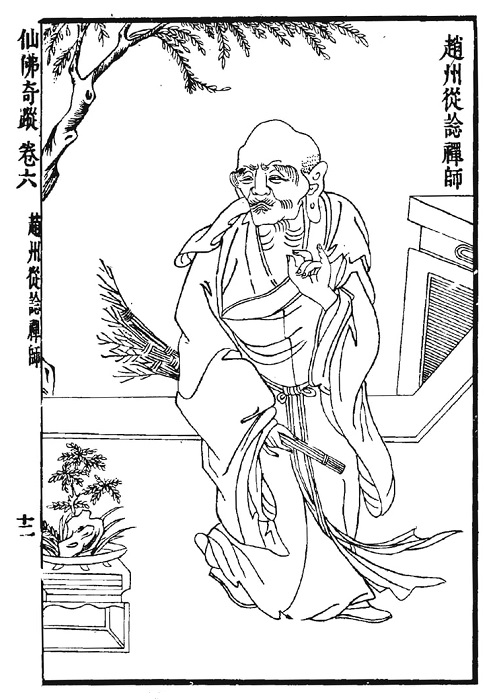

王振羽 Wang Zhenyu (1968-) illusztrációja

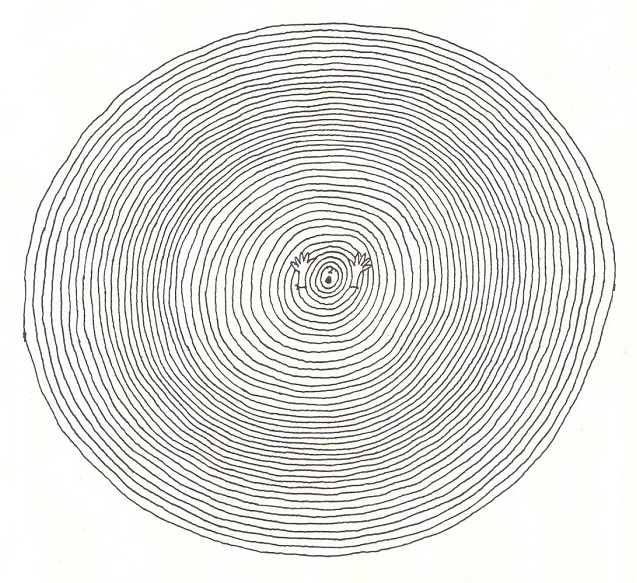

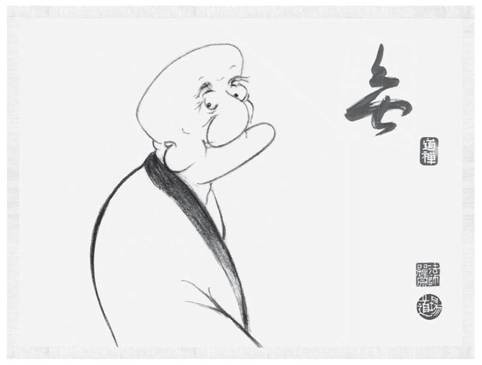

長谷川等伯 Hasegawa Tōhaku (1539-1610) illusztrációja

Lacza Márta illusztrációja

Tarnóczy Zoltán illusztrációja

– Mi a tanítási módszered? – kérdezte egy szerzetes Csao-csoutól.

– Süket vagyok, beszélj hangosabban!

A szerzetes fennhangon megismételte a kérdést.

– A tiédet máris kitanultam – mondta Csao-csou.Csao-csou megszólított egy szövegolvasásba merült szerzetest:

– Hány tekercs szútrát tudsz elolvasni egy nap?

– Általában hét-nyolc tekercset, de van, hogy tízet is.

– Akkor fogalmad sincs a szútraolvasásról!

– Miért, te hány tekercset tudsz elolvasni? – kérdezte a szerzetes.

– Én csak egy szót olvasok naponta – felelte Csao-csou.Egy szerzetes a csanról kérdezősködött Csao-csoutól.

– Ma nem felelek – mondta a mester –, olyan borús az idő.– Mi az egyetlen szó? – kérdezte egy szerzetes. Csao-csou elköhintette magát.

– Nem ez az?

– Miért, egy öregember már nem is köhöghet?– Mi az egyetlen szó? – kérdezte egy másik szerzetes.

– Mit is mondtál? – kérdezte Csao-csou. A szerzetes megismételte.

– Máris kettőt csináltál belőle – mondta a mester.– Mi az igazság végső szava? – kérdezte egy szerzetes.

– Igen – felelte Csao-csou.

A szerzetes ezt nem vette válasznak, és másodszor is feltette a kérdését.

– Nem vagyok süket! – kérte ki magának a mester.

Réber László rajzaEgy újonnan érkező szerzetes azt mondta Csao-csounak, hogy mióta elhagyta Csangant botjával a vállán, még nem ütött meg senkit.

– Akkor biztos túl rövid volt a botod – állapította meg Csao-csou.

A szerzetes nem válaszolt.

Egy szerzetes a Vutaj-hegyre zarándokolt. Útközben megkérdezett egy öreganyót, merre tartson.

– Csak egyenesen előre.

A szerzetes úgy is ment.

– Ez is csak arra tér le – mormogta utána az öreganyó.

A szerzetes elmesélte Csao-csounak, hogy járt.

– Kipuhatolom én azt az öreganyót – mondta Csao-csou.

Másnap maga is megkérdezte tőle, merre menjen.

– Csak egyenesen előre.

A mester úgy is tett.

– Ez is csak arra tér le – mormogta utána is az öreganyó.

Amikor Csao-csou visszatért, a szerzetesek már várták.

– Rajtakaptam az öreganyót – biztosította őket Csao-csou.

Lacza Márta illusztrációja

Csao-csou vándorútra kelő tanítványát csak arra intette:

– Ahol van Buddha, ott ne időzz, ahol nincs Buddha, onnan tüstént eredj tovább.

Réber László (1920-2001) illusztrációjaCsao-csou meglátogatott egy remetét:

– Itthon vagy? – kérdezte.

A remete felemelte az öklét.

– Túl sekély a víz, itt nem lehet lehorgonyozni – állapította meg Csao-csou.

Majd meglátogatott egy másik remetét:

– Itthon vagy? – kérdezte.

A remete felemelte az öklét.

– Szabadon adsz és ragadsz, éltetsz és veszejtesz – dicsérte Csao-csou, és mélyen meghajolt.– Igaz ember szájában a hamis eszme is megigazul, hamis ember szájában az igaz eszme is meghamisul – mondta egyszer Csao-csou.

Amint észrevette, hogy Csao-csou jön hozzá látogatóba, Huang-po mester magára reteszelte az ajtót.

Csao-csou befordult az Eszme Csarnokába, meggyújtott egy fáklyát, és segítségért kiáltott. Huang-po rögtön ki is nyitotta az ajtót és nekirontott:

– Beszélj, beszélj!

– Mire íjat ragadsz – szólt Csao-csou-, a rablónak híre sincs.

李蕭錕 Li Xiaokun (1949-) rajza

王振羽 Wang Zhenyu (1968-) illusztrációja

Réber László (1920-2001) illusztrációja

Élet és irodalom, 1972. július 8. XVI. évf., 28. szám, 9. oldal

Tettamanti Béla (1946-2020) rajza (1973)– Miért jött ide nyugatról Bódhidharma? – kérdezte egy szerzetes.

– Ciprusfa az udvaron – felelte Csao-csou.

– Miért jött ide nyugatról Bódhidharma? – kérdezte egy másik szerzetes.

Csao-csou mester leszállt a székéből és megállt mellette.

– Ezt feleled? – csodálkozott a szerzetes.

– Egy árva szót se szóltam – tiltakozott a mester.

Andy Warhol, Sam cat, 1954

Réber László rajzaEgy szerzetes meglátott egy macskát:

– Ez szerintem macska – szólt Csao-csouhoz. – Hát te minek hívod?

– Te macskának hívod – felelte Csao-csou.

– Azt mondják, minden visszavezethető az Egyre, de mire vezethető vissza az Egy? – kérdezte egy szerzetes.

– Egyszer Cingcsouban csináltattam magamnak egy csuhát – emlékezett Csao-csou –, annak hét font volt a súlya.– Merre van az Út? – kérdezte egy szerzetes.

– A sövényen túl – felelte Csao-csou.

– Nem azt kérdeztem!

– Hát melyiket?

– A Nagy Utat!

– Az országút pedig Csanganba visz – mondotta Csao-csou.– Mondd, honnan jöttél? – kérdezte egy szerzetestől Csao-csou.

– Délről.

– Ki volt az útitársad?

– Egy igásbarom.

– Miért barátkozik az ilyen derék szerzetes egy állattal?

– Nem vagyok én különb nála.

– Szép kis állat lehet.

– Ezt meg hogy értsem?

– Ha nem érted – mondta Csao-csou –, add vissza a barátomat!– Vajon ki az az ember – kérdezte egy szerzetes – aki nem talál társat sehol a világon?

– Az nem ember – felelte Csao-csou.– Ki a Buddha? – kérdezte egy szerzetes.

– Az ott a szentélyben – felelte Csao-csou.

– Hát az nem egy agyagszobor?

– De igen.

– Akkor ki a Buddha?

– Az ott a szentélyben.– A „Buddha” az az egy szó – mondta egyszer Csao-csou –, ami sérti a fülem.

李蕭錕 Li Xiaokun (1949-) rajza– Még egy ilyen nagy bölcs se szabadulhat a portól? – kérdezte a söprögető Csao-csout egy látogató.

– A por kívülről jön – felelte Csao-csou.

李蕭錕 Li Xiaokun (1949-) rajzaMáskor egy szerzetes szólította meg:

– Hogy találsz egy porszemet is ilyen ragyogó tiszta kolostorban?

– Nézd, itt van még egy – nyugtatta meg Csao-csou.

Tarnóczy Zoltán illusztrációja– Üres kézzel jöttem – szabadkozott egy szerzetes.

– Tedd le! – mondta Csao-csou.

– Mit tegyek le, ha egyszer semmit se hoztam?

– Akkor csak cipeld tovább!

李蕭錕 Li Xiaokun (1949-) rajza

王振羽 Wang Zhenyu (1968-) illusztrációja

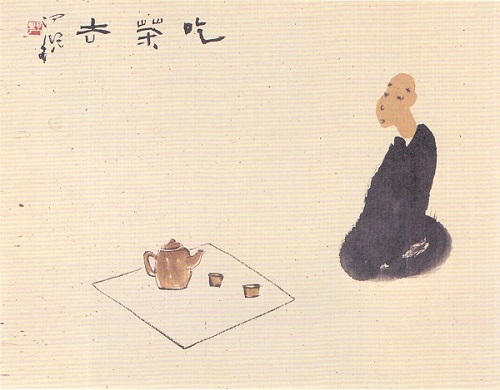

Réber László rajzaEgyik reggel Csao-csou az új szerzeteseket fogadta:

– Jártál már itt? – kérdezte az egyiket.

– Igen.

– Gyere, igyál egy csésze teát!

Aztán egy másikhoz fordult:

– Jártál már itt?

– Még nem.

– Gyere, igyál egy csésze teát!

A szerzetes-felügyelő félrehívta a mestert:

– Az egyik már járt itt, erre te megkínálod teával; a másik még nem járt itt, erre te ugyancsak teával kínálod. Jelent ez valamit?

– Felügyelő! – szólt Csao-csou.

– Tessék.

– Gyere, igyál egy csésze teát!

李蕭錕 Li Xiaokun (1949-) rajza

Réber László rajza– Most érkeztem a kolostorba – fordult egy szerzetes Csao-csouhoz. – Mondd, mi a tanításod lényege!

– Megreggeliztél már?

– Igen.

– Akkor menj, és mosd el az evőcsészédet!

A szerzetes egyszerre megvilágosult.

Mikor egy szerzetes kérdezősködni jött, Csao-csou fejére húzott csuhában fogadta. A szerzetes ácsorgott egy darabig, aztán fordult vissza.

Csao-csou utánaszólt:

– Aztán nehogy azt mondd, hogy nem válaszoltam!Egy szerzetes kihallgatást kért Csao-csoutól, de a mester kiüzent a segédjével, hogy hordja el magát.

A szerzetes meghajolt és elment.

– Az a szerzetes bebocsáttatást nyert – jegyezte meg Csao-csou –, de a segédem közben kinn rekedt.Egy nyári nap Csao-csou és tanítványa, Ven-jüan azon vetélkedett, melyikük tud mélyebbre alázkodni. Abban egyeztek meg, hogy aki alulmarad, az nyer egy süteményt.

– Én szamár vagyok – kezdte Csao-csou.

– Én a szamár fara – folytatta Ven jüan.

– Én a szamár ganéja.

– Én meg kukac a ganéjában.

– Mit csinálsz ott?

– Nyaralok.

– Nyertél – adta fel Csao-csou, és kérte a süteményt.Egyszer Csen-ting kormányzója érkezett látogatóba fiával, de a mester fel sem állt a székéből. Megkérdezte őkegyelmességét, hogy érti-e.

– Nem értem – mondta a kormányzó.

– Zsengekorom óta csak böjtölök, és annyira belerokkant a testem – magyarázta Csao-csou –, még ahhoz sincs erőm, hogy vendégeim tiszteletére leszálljak a Buddha-székből.

A kormányzó ezután még jobban becsülte Csao-csout; másnap üdvözletet is küldött tábornokával, akit Csao-csou előzékenyen felállva köszöntött.

A mester segédjét furdalta a kíváncsiság:

– A kormányzó fogadásakor tegnap el se mozdultál a székedről. Ma meg leszállsz a tábornoka kedvéért?

– Úgyse érted te ezt – mondta Csao-csou. – Ha elsőrangú a vendég, ülve kell maradni, ha másodrangú, le kell szállni, és a harmadrangú elé a templomkapun is ki kell menni.

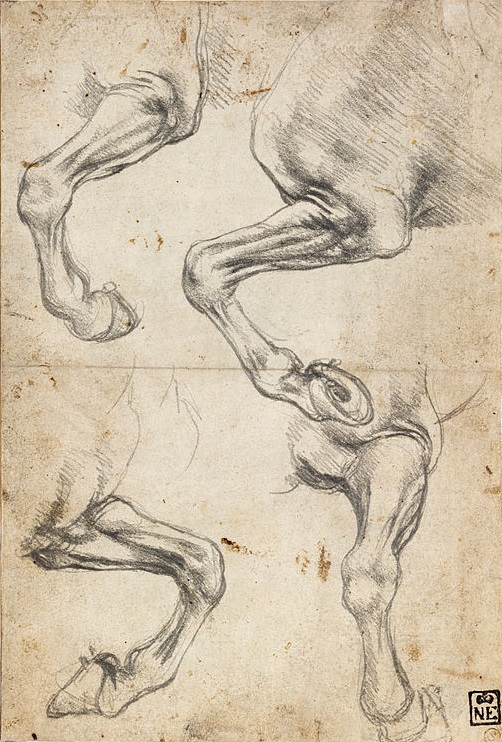

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) rajzai

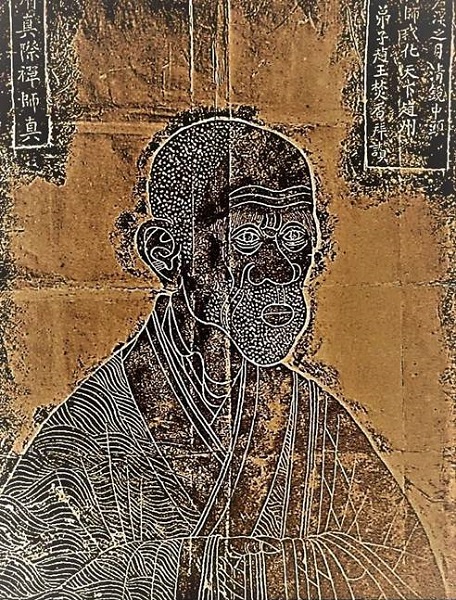

仙厓義梵 Sengai Gibon (1750-1837) rajza

李蕭錕 Li Xiaokun (1949-) rajza

Réber László rajzaEgyszer egy szerzetes megkérdezte Csao-csout:

– Van-e a kutyának buddha-természete?

– Nincs – felelte Csao-csou.

– Minden lénynek van buddha-természete, a buddháktól a hangyákig – folytatta a kérdező. – Miért épp a kutyának nincs?

– Mert válogatós.

– Hszüe feng mesterhez készülök – mondta Csao-csou egyik tanítványa. – Mit mondhatok neki?

– Télen mondj hideget, nyáron mondj meleget – tanácsolta Csao-csou.

Tarnóczy Zoltán illusztrációjaEgy szerzetes a csan legfontosabb alapelvét tudakolta, de Csao-csou mester kimentette magát:

– Pisálni kell mennem – mondta. – Látod, még egy ilyen kis dolgot is magam intézek el.

Ismeretlen

Tettamanti Béla (1946-2020) rajza (Árnyékváltás, 1981-86)Csao-csou elcsúszott a behavazott gyalogúton:

– Segítség, segítség! – kiáltozta.

Egy szerzetes odasietett és lefeküdt mellé a hóba. Csao-csou feltápászkodott és ment tovább.

Tarnóczy Zoltán illusztrációjaCsao-csou ellátogatott egyszer Pao-sou [Pao-sou Jen-csao, 830-888] mesterhez, aki úgy fogadta, hogy hátat fordított neki magas székén.

Csao-csou leterítette rongyszőnyegét a földre, és arcra borult.

Pao-sou erre leszállt a székéből, de közben Csao-csou már sarkon fordult.

A mester tüzet csiholt, és közben odaszólt egy szerzetesnek:

– Ezt én fénynek nevezem. Hát te?

A szerzetes nem szólt semmit.

– Ha nem fogod fel a csan értelmét – jegyezte meg Csao-csou –, fölösleges csöndben maradnod.Egy apáca a titkos tanításról faggatózott Csao-csou-nál.

A mester megérintette az apáca szemérmét.

– Tisztelendőséged még mindig ilyen? – szörnyülködött az apáca.

– Nem én vagyok ilyen, hanem te! – állapította meg a mester.

Zensho W. Kopp illusztrációjaCsao-csou így beszélt egyszer az egybegyűlt szerzetesekhez:

– A bronz-Buddha megolvad a kemencében, a fa-Buddha elég a tűzben, a vályog-Buddha szétázik a vízben. De az igaz Buddha mibennünk él. Megvilágosulás és Nirvána, Nyilvánvalóság és Buddhatermészet – mindezek csak rosszul szabott göncök rajta. Szennyeződések. De ha nincs kérdés, nincs szennyeződés. Valójában nincs amihez ragaszkodhatnátok. Ha nem kavarognak bennetek gondolatok, sehol sem követhettek el hibát. Hogy felismerjétek a valóságot, csupán üljetek le nyugodtan vagy húsz-harminc évre, s ha ezek után is értetlenek maradtok, leüthetitek ennek az öregembernek a fejét. Minden olyan, mint egy álom, egy látomás, egy légvirág, s szaladgálni utánuk hiábavaló foglalatosság. Ha nem kalandoztatjátok el folyton a gondolataitokat, minden rendben lesz. Semmi nem jön kivülről, mire jó hát ez a sündörgés? Mi sarkall benneteket arra, hogy körbe keresgéljetek, mint a kutyák, akik minden sarokba bedugják az orrukat, s minden vacakot a szájukba vesznek? Emlékszem, Si-toutól bárki bármit kérdezett, ő csak azt mondta: „Fogd be a szád, ne ugass, mint egy kutya!" Én is azt mondom nektek: „Ne csaholjatok!"

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) rajza– Régóta hallom emlegetni a híres csaocsoui kőhidat – szólt egy vándorszerzetes Csao-csouhoz –, de itt csak néhány cölöpöt és pallót látok.

– Egy közönséges fahídtól meg se látod a csaocsoui kőhidat – mondta Csao-csou.

– Mi volna az a csaocsoui kőhíd?

– Átmegy azon a szamár is, a ló is!

Réber László (1920-2001) vázlataEgy szerzetes a kilétéről kérdezte Csao-csout:

– Ki az a Csao-csou?

– Keleti kapu, nyugati kapu, északi kapu, déli kapu – felelt Csao-csou.

Csao-csou portréja, mai koreai templomi festmények

Zhaozhou Congshen: A tizenkét óra dala

Hadházi Zsolt fordítása

http://zen.gportal.hu/gindex.php?pg=4792614&nid=6160916

Kakaskukorékolás, az első óra.

Kedvtelenül, de mégis fölkelek.

Se alsó, se felső ruha nincsen,

Csak épphogy valami köntöshöz hasonló.

Gatya derék nélkül, szakadt nadrág,

Fejemen harmincöt kiló fekete korom.

Így gyakorolni és segíteni embereken,

Ki gondolná, hogy ostobaság?Hajnalhasadás, a második óra.

Romos templom elhagyott faluban, nincs mit mondani róla.

A reggeli kásában egy szem rizs sincs,

Az ablak koszos repedéseit nézem dologtalanul.

Csak verebek csivitelnek, nincs kivel ismerkedni,

Egyedül ülök, néha hulló leveleket hallok.

Ki mondta, hogy az otthont elhagyni a vágy és harag feladása?

Ha erre gondolok, akaratlanul is könnyek nedvesítik kendőmet.Napkelte, a harmadik óra.

A tisztaság szenvedélyekké válik.

Az érdemek létrehozása szennyel fed be,

Még sosem söpörték fel a végtelen mezőt.

A homlok gyakran ráncos, a szív ritkán elégedett,

Nehéz kijönni a keleti falu aszott öregjeivel.

Adományokat ide egyszer sem hoztak,

Kóbor szamár eszi csarnokom előtt a füvet.Étkezés ideje, a negyedik óra.

Hiába próbálok tüzet gyújtani, csak nézem innen-onnan.

A kekszek és sütemények tavaly elfogytak,

Ma rájuk gondolok és üresen nyelem a nyálamat.

Ritkán marad valami, gyakran sóhajtozom,

A sok ember között nincs senki jó.

Csak egy teát kér aki ide jön,

És mikor nem kap dühösen megy el.Délelőtt, az ötödik óra.

A fejemet borotválom. Ki gondolta volna, hogy így lesz?

Semmi okom nem volt falusi szerzetesnek állni,

Megvetett, éhes, magányos; halálvágyam van.

Az emberek általában

Egy kicsit sem tiszteltek soha.

Épp csak most érkeztél az ajtómhoz,

De csak teát és papírt kértél kölcsön.Nap délen, a hatodik óra.

Körbejárok teáért és rizsért, nincs szabott menet.

Elmentem a déli házakhoz, megyek az északiakhoz,

Igen, az északiakig, csak kifogásokat kapok.

Keserű só, savanyú árpa,

Köles-rizs tészta mángolddal.

Csak hogy ne nevezzék az adomány elhanyagolójának,

A szerzetes Út-tudata szilárd kell legyen.Süllyedő nap, a hetedik óra.

Felforgatva a dolgokat, nem járok fény és árny földjén.

Valamikor hallottam: egyszer jóllakni száz nap éhezést feledtet.

Ma ennek az öreg szerzetesnek teste pont ilyen.

Nem gyakorlok meditációt, nem beszélgetek az igazságról,

Kiterítem ezt a szakadt gyékényt és nappal alszom.

Ábrándozhatsz a Tusita mennyen is túlra,

De nem fogható ahhoz, ahogy a nap süti a hátamat.Késő délután, a nyolcadik óra.

És valaki füstölőt éget és leborulásokat végez.

Az öt öreg asszonyból három golyvás,

Kettőnek ráncoktól fekete az arca.

Lenolaj tea, az valóban ritka,

A vadzsra őrök nem kell izmaikat feszítsék.

Remélem, hogy jövőre, mikor a selyem és az árpa megérett,

Ráhula-dzsi ad nekem egy szót.Nap lemenőben, a kilencedik óra.

A pusztaságon kívül mit lehetne még őrizni?

A szerzetes nagysága a kötöttségek nélküli áramlás,

Templomokat járó novíciusé az örökkévalóság,

Mintán túli szavak nem a szájból jönnek,

Hasztalanul folytatom, ahol Sákjamuni fiai abbahagyták.

Egy durva eperfa bot,

Nem csak hegymászásra, kutyák elzavarására is.Aranyló alkony, a tizedik óra.

Egyedül ülök a sötét üres szobában.

Sosem éri gyertyaláng fénye,

A szemem előtti tisztaság mély fekete.

Harangot nem hallok, a nap időtlen múlik,

Csak az öreg patkányok neszezése hallatszik.

Mi kell még, hogy legyenek érzéseim?

Bármi is jut eszembe, az a páramitá gondolata.Alvásidő, a tizenegyedik óra.

A kapu előtt a hold vajon kit irigyel?

Visszamenve csak az aggaszt, ideje lefeküdni.

A viselt ruhán kívül miféle takaró kéne?

Vezető szerzetes Liu, aszkéta Zhang,

Ajkaikkal jóságról beszélnek, mily csodás!

Hagyom, hogy kiürítsd üres zsákomat,

Ha kérdeznéd sem fognád fel az okát.Éjfél, a tizenkettedik óra.

Ez az érzés hogyan szűnhetne egy pillanatra is?

Gondolva mindazokra, akik elhagyták az otthont,

Úgy tűnik régóta vagyok apát.

A föld az ágyam, szakadt gyékény a matracom,

Öreg fedetlen szilfarönk a párnám.

A szent képnek senki nem ajánl fel arab füstölőt,

A hamuban csak az ökör szarását hallja.Források:

CBETA: X68n1315, p90, b11-c23

James Green: The Recorded Sayings of Zen Master Joshu, p. 171-175Jegyzetek (versszak.sor):

Zhaozhou Congshen (778-897): fiatalon avatták fel szerzetesnek, Nanquan Puyuan (748-835) tanítványa volt húsz éven át, utána számos más mestert látogatott, végül 80 évesen telepedett meg északon Zhao tartományban (Zhaozhou), ahonnan nevét is kapta. A Hongzhou iskola kiemelkedő mestere volt, fennmaradt beszédeit a X. században Qixian Chengshi gyűjtötte össze, állítólag egy korábbi mű alapján.

1.1: minden óra kettő nyugati órának felel meg, tehát az első óra az reggel 1-3 óra.

1.3: a szerzetesi ruha részei

1.4: köntös (szanszkrit: kasaja): nagy méretű külső szerzetesi ruha

2.7: elhagyni az otthont annyi, mint szerzetesnek állni

3.2: szenvedély (szkt: klésa): a tudatot szennyező indulatok

3.3: érdem és szenny (szkt: punja és upaklésa): jó tettek és ragaszkodás világi dolgokhoz

3.4: a szerzetes az érdemek mezeje

3.8: a csarnok a buddhista kolostor fő része

5.5: szó szerint "Csang és Li", nem konkrét személyeket jelölő nevek

6.2: koldulni megy

6.8: Út-tudat: a megvilágosodás tudata

7.1: fény és árny azt is jelenti, hogy idő

7.7: Tusita menny az, ahol az eljövendő buddha Maitréja lakik

8.2: buddhista szertartás

8.6: a vadzsra őrök a templomok kapujánál álló védelmező szobrok

8.8: Ráhula, a Buddha egyik tanítványa, aki a mantrák - ezoterikus szavak, igék - ismerője volt; a "dzsi" tiszteletteljes jelző

9.4: novícius a szanszkrit sramanéra fordítása

10.4: a mély fekete itt eredetileg Csin tartományi lakk

10.5: harang jelezte az időt

10.7: hétköznapi emberi érzésekről van szó

10.8: páramitá (szkt: átment): a megvilágosodás túlpartja, tehát minden gonodolat megvilágosodott gondolat

11.7: a zsák jelenti a pénzes zsákot és a testet is, a második értelemben a zsák kiürítése a halál

12.2: ez az érzés: a megvilágosodás állapota

12.7: a szent kép a Buddha szobrát jelenti; az arab füstölő a legdrágább fajta volt

Jōshū zenji goroku 趙州禅師語錄 by Suzuki Daisetsu 鈴木大拙 and Akizuki Ryōmin 秋月龍珉

Tokyo: Shunjūsha. 1964

PDF: Radical Zen : the sayings of Jōshū / translated with a commentary by Yoel Hoffmann ; pref. by Hirano Sōjō.

Brookline, Mass. : Autumn Press; 1978. 160 p.

PDF: The Recorded Sayings of Zen Master Joshu / translated and introcuced by James Green ; with a foreword by Keido Fukushima Roshi.

Altamira Press, A Division of Sage Publications, Inc.

Walnut Creek, London, New Delhi, 1998.

Ts’ung-shen of Chao-chou (778-897?)

by John C. H. Wu

Chapter VII

In: The Golden Age of Zen

Taipei : The National War College in co-operation with The Committee on the Compilation of the Chinese Library, 1967, pp. 126-146.

Master Ts’ung-shen is commonly known as “The Ancient Buddha of Chao-chou,” or simply as “Chao-chou,” in Ch’an circles, because he was for a long period the Abbot of the Kuan-yin Monastery in the District of Chao-chou, in what is today the province of Hopeh. In these pages, we shall call him Chao-chou in conformity to the general custom.

Chao-chou came from a Ho family of Ts’ao-chou in Shantung. Born in 778, he is said to have lived to his one hundred and twentieth year, according to the Record of Transmission of the Lamp. But another source tells us that Chao-chou died in 869. In that case, he would have lived no more than ninety-one years. It is hard to tell which statement is correct, although the former view represents the prevailing tradition.

He began early in life as a novice in a local monastery. Before his profession he traveled southward to visit master Nanch’üan in Ch’i-chou, Anhui. It happened that at the time of his arrival Nan-ch’üan was resting, stretched out on his back on his couch. On seeing the young visitor, the master asked, “Where do you come from?” “I come from the Jui-hsiang (Holy Image) Monastery,” Chao-chou replied. “Do you still see the Holy Image?” the master asked. “No,” answered the visitor, “I do not see the Holy Image, I only see the sleeping Tathagatha!” Struck by the strange answer, the master sat up and asked him, “Are you a free shramana (monk), or one belonging to a master?” “One belonging to a master,” declared Chao-chou. Upon being asked who his master was, Chao-chou made no answer but simply paid his obeisance, saying, “In this wintry season, the weather is so very cold. I wish Your Reverence good health.” This was how Chao-chou chose his predestined master. As for Nanch’üan, he must have welcomed his predestined disciple as a windfall. At any rate, he had the highest esteem for the new-comer and admitted him immediately into his inner chamber.

When Chao-chou asked his master, “What is the Tao?” the latter replied, “Tao is nothing else than the ordinary mind.” “Is there any way to approach it?” pursued Chao-chou further. “Once you intend to approach it,” said Nanch’üan, “you are on the wrong track.” “Barring conscious intention,” the disciple continued to inquire, “how can we attain to a knowledge of the Tao?” To this the master replied, “Tao belongs neither to knowledge nor to no-knowledge. For knowledge is but illusive perception, while no-knowledge is mere confusion. If you really attain true comprehension of the Tao, unshadowed by the slightest doubt, your vision will be like the infinite space, free of all limits and obstacles. Its truth or falsehood cannot be established artificially by external proofs.” At these words Chao-chou came to an enlightenment. Only after this did he take his vows and become a professed monk.

On another day, Chao-chou asked his master, “When one realizes that ‘there is,’ where should he go from there?” “He should go down the hill,” came the surprising answer, “to become a buffalo in the village below!” But even more surprising was Chao-chou’s reaction. Far from being mystified, he thanked his master for having led him to a thorough enlightenment. Thereupon, Nan-ch’üan remarked, “Last night at the third watch, the moon shone through the window.”

The above two conversations are of capital importance. They establish the foundation of Chao-chou’s inner vision and spiritual realization. They furnish the key to the understanding of all sayings and actions in his long pilgrimage of life. Let us, therefore, look at them more closely before we proceed to the rest.

In the first dialogue, Nan-ch’üan began by uttering one of the central insights of Ch’an: Tao is nothing else than the ordinary mind. Then he proceeded to point out that Tao is beyond knowledge and no-knowledge, that it cannot be attained by deliberate seeking, nor proved or disproved by discursive arguments. Nan-ch’üan does not tell us how to attain a true comprehension of Tao; but he has stated very clearly the effect of such comprehension: Your vision will be like the infinite space, free of all limits and obstacles. This, I believe, points up the transcendence of Tao. If Tao is nothing else than the ordinary mind; then the ordinary mind must be very extraordinary indeed.

In the second dialogue, we first encounter a typical Ch’an idiom: To realize that “there is.” In ordinary language, it signifies, “To comprehend Reality or Pure Being,” which is none other than Tao. By direct comprehension one becomes one with the Tao. Chao-chou was asking where a man could go when he has become one with Tao, since Tao, as Chuang Tzu had truly said, is nowhere and everywhere. Meaning to bring out graphically the immanence of Tao, Nan-ch’üan declared that such a man should go down the hill to become a buffalo in the village below. The buffalo was, of course, only a random instance employed by the master to clinch the attention of the disciple. This was on a par with Chuang Tzu’s pointing to a particular pile of excrement saying that Tao was there. But Nanch’üan was more fortunate than Chuang Tzu; for while Chuang Tzu’s words only resulted in driving away his listener, Nanch’üan’s words occasioned a complete enlightenment in his disciple. To be one with Tao is to be one with the whole universe and each and everything in it! Chao-chou was inundated with this wonderful insight, until his whole being was filled with it. As Nan-ch’üan put it, the bright moonlight had penetrated the windows of his soul.

Now, to be enlightened is to be emancipated from illusions and inhibitions. This explains certain actions, especially in the case of newly enlightened persons, which might easily shock the usual conventionally-minded gentlemen. In the exercise of their newly won freedom, their master has often been the first person to receive their rough-handling. Curiously enough, many a master seems to have enjoyed the apparent indignities received from his disciple. When Lin-chi slapped Huang-po, the latter burst out laughing. Nan-ch’üan fared no better with Chao-chou. Once Nan-ch’üan said to Chao-chou, “Nowadays it is best to live and work among members of a different species from us.” (This statement may be unintelligible to those who are unfamiliar with the Buddhist proverb: It is easier to save the beasts than to save mankind, ) Chao-chou, however, thought otherwise. He said, “Leaving alone the question of ‘different,’ let me ask you what is ‘species’ anyway?” Nan-ch’üan put both of his hands on the ground, to indicate the species of the quadrupeds. Chao-chou, approaching him from behind, trampled him to the ground, and then ran into the Nirvana Hall crying, “I repent! I repent!” Nan-ch’üan, who appreciated his act of trampling, did not understand the reason of his repentance. So he sent his attendant to ask the disciple what he was repenting for. Chao-chou replied, “I repent that I did not trample him twice over!” Thereafter the master esteemed and loved him more than ever.

What a topsy-turvydom is the world of Ch’an! Yet, if we remember that Nan-ch’üan made that statement with no other purpose than to test the authenticity and depth of his disciple’s enlightenment, and if we understand that Chao-chou’s act of trampling was meant only to wipe out the very notion of “species,” we could easily realize that there is method in all their madness.

Although Nan-ch’üan was the Abbot of a large community of monks and novices, Chao-chou was the only man after his heart. In fact, the master and the disciple seem to have cooperated closely in the work of initiating the others. At first, Chaochou was made to serve in the kitchen as the stoker. One day he closed all the doors and piled wood on the fire until the whole kitchen was filled with smoke. Then he shouted, “Fire! Fire! Come to my rescue!” When the whole community had flocked to the door, he said, “I will not open the door unless you can say the right word.” No answer came from the crowd. But the Abbot silently passed the key through a window hole. This was the right word that Chao-chou had in mind, and he opened the door immediately.

No one knows exactly what was behind it all. But if we take the whole episode as a pointer to the process of enlightenment, it may reveal to us a part of its hidden significance. For, is not enlightenment after all the opening of the mind’s door at the occasion of the “right word?” It is also interesting to note that the “right word” is not necessarily something oral, but may consist in silence or in a simple action like the passing of the key in this case. Another lesson is that the door, if it is to be opened at all, must be opened from the inside. Finally, as the story shows, the stoker could have opened the door even without the key. The master, in passing the key through the window-hole, actually did not contribute anything substantial to the opening of the door. His action was no more than an echo to the voice inside. That’s why no Ch’an master has ever boasted of his power even though he should have been instrumental to the enlightenment of a great number of his disciples. This is what Thomas Merton calls “ontological” or “cosmic” humility, which he has so aptly attributed to Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu.1 It can with equal appropriateness be attributed to the great masters of Ch’an, who, as Merton observes, are the “true inheritors of the thought and spirit of Chuang Tzu.”

How completely Chao-chou saw eye-to-eye with his master can be inferred from another episode. It happened that the monks of the eastern and western halls of the monastery were quarreling over the possession of a cat. Nan-ch’üan seized the cat, saying to the monks, “If any of you can say the right word, the cat will be spared.” As no one answered, he ruthlessly cut the cat in half. When Chao-chou returned in the evening, the master told him about the whole incident. Chao-chou did not say anything, but, removing his sandals from his feet and putting them on his head, he walked out. The master said, “If you had been here, you would have saved the cat!”

This is one of the most frequently discussed cases in the literature of Ch’an. Why did Nan-ch’üan take such a drastic and merciless action upon the innocent cat? What did he wish to teach by cutting it into two pieces by a single stroke of his knife? What did Chao-chou mean by putting his sandals on his head and walking out? Why did Nan-ch’üan say that this eccentric action would have constituted the right word he had expected from the community, which would have saved the life of the poor cat? The simplest way of disposing of all these questions would be to say that Ch’an is something beyond sense and therefore cannot be explained at all. No doubt, Ch’an is beyond sense; but it must be remembered that it is also beyond nonsense. Although there can be no logical answer to any of these questions, yet nothing prevents us from perceiving some of the psychological and spiritual motives impelling the two masters of Ch’an to act the way they did. If Nan-ch’üan’s action was shocking, it was intended to shock his monks out of their attachment to the cat. Nan-ch’üan himself must have been shocked to find the “home-leavers”—as monks were called—still tied to a cat. All ties must be cut once for all if one is to be a true monk. It is only through ruthless violence that one can be started on the road to freedom and spontaneity. I am not sure whether the means Nan-ch’üan employed were the best under the circumstances; but there can be no question that the end-in-view was to teach his monks an unforgettable lesson in spiritual liberation. Likewise, Chao-chou’s action of putting his sandals on his head and walking out may appear completely arbitrary; but it was certainly meant to remind his fellow monks of the realm of Reality in which the values of this world are turned upside down, and in which the legal rights and wrongs, over which the worldlings fight so seriously, exist no more. Incidentally, his funny behaviour must have served to soothe the nerves of his excited master—for even enlightened ones have their emotional life—as if he were saying, “Good night, master! Take it easy, and have a good rest.”

After his enlightenment, Chao-chou spent many years in traveling and visiting contemporary Ch’an masters, not so much in order to receive further instruction from them as to exchange notes with them. He was fond of mountains and rivers, and was very much at home roaming from one place to another. Several of his friends advised him to settle down with a community of his own, but he had no such desire. Once, as he was visiting Chu-yu, the latter said, “A man of your age should try to find a place to settle down and teach.” “Where is my abiding place?” Chao-chou asked back. “What?” said his host, “With so many years on your head, you have not even come to know where your permanent home is!” Chu-yu was, of course, referring here to the obvious truth that the True Man is his own abiding place. It is so obvious a truth as to make its articulation quite silly. So Chao-chou said, “For thirty years I have roamed freely on horseback. Today, for the first time I am kicked by an ass!”

When he was on the point of starting for the Ch’ing-liang Temple on Five-Story Mountain in Shansi, a learned monk wrote a gatha to tease him:

What green mountain is not a center of Tao?

Must you, cane in hand, make a pilgrimage to Ch’ingliang?

Even if the golden-haired lion should appear in the clouds,

It would not be an auspicious sight to the Dharma-Eye!(Note: The temple on Five-Story Mountain was built in honor of National Teacher Ch’ing-liang, the Fourth Patriarch of the Hua-yen sect. It is said that when he preached on the mountain, a golden-haired lion appeared in the clouds).

But Chao-chou was not to be dissuaded from his trip. He answered the gatha by asking back, “What is the Dharma-Eye?” The monk could find no answer. He should have known that together with the cane Chao-chou brought the Dharma-Eye wherever he went.

It was not until he was around eighty that he settled at the Kuan-yin Monastery in the eastern suburb of Chao-chou. It is said that he was extremely ascetic in his habits. During the forty years of his abbotship, he did not install a single piece of new furniture, nor did he write a single letter to any patron to ask for alms. (He would be considered a very inefficient abbot according to the standards of the modern West).

But Chao-chou was too well-known to be left alone by the world. Once a very powerful prince came to visit him. Chaochou kept seated and asked the visitor, “Does Your Highness understand?” The prince said, “I do not understand.” The master said, “Since my childhood I have been keeping fasts. Now that I am old, I do not possess enough energy to rise from my Ch’an couch to receive my guests.” Far from being offended, the prince respected him all the more. The next day he dispatched a general to convey his appreciation. The master came down immediately to receive him. After the general was gone, an attending monk asked the master, “When the great prince came, you did not come down from the couch to welcome him. But today, as soon as you saw his general, you came down immediately to greet him. What kind of protocol is that?” The master replied, “This is something you do not understand. When a first-rate man comes, I receive him while remaining seated. When a second-rate man comes, I come down from my seat to receive him. When a man of the lowest class comes, I would go out of the front gate to receive him.” Evidently he was no longer speaking of the protocol of social intercourse, but expounding the degrees of accommodation in dealing with different grades of spiritual potentiality.

We have already mentioned that Chao-chou was called “The ancient Buddha of Chao-chou.” This title was given him by Hsüeh-feng, a prominent Ch’an master in southern China. It is not known whether they ever met in person. But on a certain day, a monk, who came from the south to visit Chao-chou, related to him the following dialogue between Hsüeh-feng and a disciple of his:

Disciple: Can you tell me something about the “cold spring of the ancient brook”?

Hsüeh-feng: However hard you gaze into it, you cannot see its bottom.

Disciple: What happens to the drinker?

Hsüeh-feng: He does not drink it with his mouth.

At this point, Chao-chou remarked humorously, “Since he does not drink it with his mouth, I suppose he does it with his nose.” The visitor said, “What would you say about the ‘cold spring of the ancient brook?’” “It tastes bitter,” he replied. “What happens to the drinker?” the visitor further asked. “He dies!” said Chao-chou.

When Hsüeh-feng heard of this dialogue, he burst into praise, saying, “The ancient Buddha! The ancient Buddha!” This was how the title originated.

The “cold spring of the ancient brook” signifies nothing else than the Tao. That “it tastes bitter” means that you have to go through the strictest self-discipline and deprivation in the pursuit of Tao, till you are thoroughly dead to the world and to yourself. Without bitterness there can be no true joy. Without death there can be no real life. This dialogue reveals the hidden spring of Chao-chou’s gaiety and vitality, his profound wisdom and light-hearted humor.

Once a Confucian scholar came to visit him. Greatly impressed by his wisdom, the guest exclaimed, “Your Reverence is indeed the ancient Buddha!” He immediately returned the compliment by saying, “But you are the new Tathagata!” This was, in fact, more than a mere exchange of compliments. The repartee of Chao-chou was meant, I think, to be a subtle rectification of the term “ancient Buddha.” The True Self is ever new. An ancient Buddha would be a dead Buddha.

It is the common aim of all Ch’an masters to lead their novices to the True Self. This is also the end of Chao-chou’s teachings. But his way of accomplishing it was altogether original and funny.

One morning, as he was receiving new arrivals, he asked one of them, “Have you been here before?” “Yes,” the latter replied. “Help yourself to a cup of tea,” he said. Then he asked another, “Have you been here before?” “No, Your Reverence, this is my first visit here.” Chao-chou again said, “Help yourself to a cup of tea.” The Prior of the monastery took the Abbot to task, saying, “The one had been here before, and you gave him a cup of tea. The other had not been here, and you gave him likewise a cup of tea. What is the meaning of all this?” The Abbot called out, “Prior!” “Yes,” responded the Prior, “what’s your bidding?” “Help yourself to a cup of tea!” said the Abbot.

The act of drinking tea is but the functioning of someone, and in each case it should evoke the question, who is drinking the tea? Besides, if Tao is nothing else than the ordinary mind, every ordinary action is an expression of Tao. A novice once said to the master, “I am only newly admitted into this monastery, and I beseech Your Reverence to teach and guide me.” The master asked, “Have you taken your breakfast?” “Yes, master, I have.” “Go wash your bowl,” said the master. At these words, the novice experienced an instantaneous enlightenment.

Like Chuang Tzu, Chao-chou may be called a “cosmic democrat.” In his Weltanschauung, all things are equal, because Tao is present even in what the world looks upon as the lowest things.

On a leisurely summer day, Chao-chou was sitting idly in his room, with his faithful disciple Wen-yüan attending on him. By a fluke a bright idea came into the head of the jolly old man. “Wen-yüan,” he said, “let us enter into a contest as to which of us can identify himself with the lowest thing in the scale of human values.” It was agreed that the winner was to pay the loser a cake. Wen-yüan gladly accepted the challenge, but deferred to the master to start. Chao-chou began: “I am an ass.” Wen-yüan: “I am the ass’s buttock.” Chao-chou: “I am the ass’s feces.” Wen-yüan: “I am a worm in the feces.” At this point, Chao-chou could not go further, so he asked, “What are you doing there?” Wen-yüan replied, “I am spending my summer vacation there.” Thereupon, Chao-chou said, “You win!” and demanded the cake.

This was the only recorded case where the resourceful Abbot admitted his defeat. But I suspect that the old man was hungry, and he was only too eager to lose the contest in order to win the cake.

I have often wondered why certain sages seem to have taken a delight in mentioning things which are offensive to delicate ears. Chuang Tzu used to say that Tao is in the excrement. Justice Holmes used to doubt if cerebration had a greater cosmic validity than the movement of bowels. But to Chuang Tzu and the Ch’an masters, there can be no doubt that the movement of bowels possesses cosmic validity, though the same cannot be said of mere cerebration.

To the pure all things are pure. But to the impure, even the purest things can be impure. One morning, a nun besought Chao-chou to tell her “the secret of all secrets,” which in Buddhist parlance means the most fundamental principle. The ancient Buddha just patted her on the shoulder. Evidently he wished thereby to indicate that the most fundamental principle was within her. But the nun was taken aback by the ancient Buddha’s unexpected action. “I am shocked,” she exclaimed, “to see that Your Reverence has still got that in him!” “Rather it is you, Sister,” Chao-chou retorted, “who have still got that in you!” The very quickness of his repartees reveals that they flowed from an unencumbered heart.

To Chao-chou, Reality is not to be found in formulated principles and mottoes. Once a monk asked him, “What is the one motto of this monastery of Chao-chou?” The master replied, “There is not even a half motto here.” “Don’t we have Your Reverence here as the Abbot?” the monk queried. “But this old monk is not a motto!” said Chao-chou.

A true descendant of Hui-neng, Chao-chou’s eyes were steadfastly focussed on the self-nature, which was for him but another name for Tao or Reality. In a remarkable sermon, he declared, “Thousands upon thousands of people are only seekers after Buddha, but not a single one is a true man of Tao. Before the existence of the world, the self-nature is. After the destruction of the world, the self-nature remains intact. Now that you have seen this old monk, you are no longer someone else, but a master of yourself. What’s the use of seeking another in the exterior?” On another occasion he said, “The one word which I dislike to hear is ‘Buddha.’”

For Chao-chou, as for Ma-tsu and Nan-ch’üan, Tao or Reality is neither mind, nor Buddha, nor a thing. It transcends the universe of time and space, yet it pervades all things. It is only against this metaphysical background that we can understand some of his enigmatic sayings. For instance, when a monk asked him, “What is the real significance of Bodhidharma’s coming from the West?” (by a consensus of opinion among Ch’an masters, this question meant nothing else than: “What is the essential principle of Buddhism?” or, to put it more simply, “What is Tao?”), his answer was, “The cypress tree in the courtyard.” When the monk protested that the Abbot was only referring him to a mere object, the Abbot said, “No, I am not referring you to an object.” The monk then repeated again the question. “The cypress tree in the courtyard!” said the Abbot once more.

Stripped of the jargon of Ch’an, all that Chao-chou was saying was that Tao is in the cypress tree in the courtyard. In fact, it is in all things. The cypress tree was mentioned simply because it happened to be the first thing that he saw. If he had seen an eagle flying over, he would have said, “The eagle in yonder sky!” True, he mentioned an object; but he was using it to point to Tao. He was not referring the monk to a mere object; it was the monk whose vision was glued to the object so that it could not pass beyond it.

Chao-chou’s view of Tao is on all fours with that of Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu. This is not because he followed them deliberately, but because his insights happened to coincide with theirs. On the other hand, he did not agree entirely with the view of Seng-ts’an, the Third Patriarch of Ch’an, as presented in the following stanza:

There is no difficulty about the pursuit of Tao,

Except that we must refrain from making discriminations.

If a man can only free himself of likes and dislikes,

He will see clearly as in broad daylight.Chao-chou took exception to it in a conference. “The moment you utter a single word, you have already made a choice, while imagining yourself to be in the light. As for me, I am not in the light about it. I only want to know whether you still cherish it and preserve it intact in your heart.” At this point, a monk asked him, “Since you are not in the light about it, what is it, then, that you wish us to cherish and preserve intact?” “I don’t know any more than you do,” the Abbot replied. The monk further asked, “Since you are so clear about your not knowing, how can you say that you are not in the light?” Instead of giving the final answer, the master evaded the question by saying, “Please confine your questions to the realm of things.” After performing the rites of worship, the assembly was dismissed.

The monk in this case was probably not a neophyte in Ch’an learning. He was perhaps trying to press the master to articulate his philosophic creed somewhat in the way Lao Tzu had done when he said:

To realize that our knowledge is ignorance,

This is a noble insight.To regard our ignorance as knowledge,

This is mental disease.But Chao-chou had the knack of glancing off the target instead of sticking in the bull’s-eye. Like all the great masters of Ch’an, Chao-chou kept the feet of his disciples on a slippery ground in order to prevent them from slipping into the snug den of a clean-cut formula. When Ma-tsu said, “Slippery is the road of Shih-t’ou!” it was meant as a compliment to his great contemporary in the world of Ch’an.

But no one can be more slippery than Chao-chou. Once a monk asked him, “It is said that all things return to the One. Where does the One return to?” The master said, “When I was in Ch’ing-chou, I made a robe of cotton cloth, weighing seven catties.” What an irrelevant answer! This dialogue has been used in the succeeding generations as a typical kung-an to tease the minds of neophytes. But we must remember that to Chao-chou the One and many are relative and interpenetrated. If the many return to the One, the One returns to the many, so that any particular event, however trivial it may appear, in whatever place and time it may happen, is inseparably connected with the One and may therefore serve as a pointer to it. Now, nothing could be more particular than the fact that when he was in Ch’ingchou he had a robe of cotton cloth made for him, which weighed seven catties. On the other hand, nothing could be more universal than the One. Yet, in none of the infinite number of particulars is the One ever absent!

But did Chao-chou equate the One with Tao? By no means! If he did, Tao itself would have been conceived as relative. The truth is that in his view, Tao is absolutely beyond one and many. This seems to be the pivotal point in his philosophy. Even in his early days, when he was with Nan-chuan, he already had a clear grasp of the utter transcendence of Tao. After quoting to his master a popular saying: “Tao is not outside of the realm of things; outside of the realm of things there is no Tao,” he asked, “What about the transcendent Tao?” Nan-ch’üan struck him. Catching hold of the cane, Chao-chou said, “Hereafter, take care not to hit the wrong person!” That won from Nan-ch’üan a wholehearted commendation: “It is easy to distinguish the dragon from the snake, but it is next to impossible to deceive a true monk.”

Tao is not only beyond the one and many, but also beyond yu and wu, or the phenomenal and the noumenal . Chao-chou’s extreme flexibility in handling all relative terms springs directly from his constant awareness of the utter transcendence of Tao. Once he was asked if the dog possessed the Buddha-Nature. He answered, “No!” This flatly contradicts an essential tenet of Buddhism. So the questioner further asked, “There is BuddhaNature in all beings, from the Buddhas to the ants. How can you say that the dog has no Buddha-Nature?” The master replied, “Because of its habit of discrimination.” On another occasion, when exactly the same question was put to him, he answered, “Yes” But the questioner said, “Since the dog has BuddhaNature, how did he come to assume the body of a dog?” “He acted against his better knowledge,” the master replied.

If the same question were put to Chao-chou for the third time, he might well have answered, “Yes and no!” Yes, that is, in one sense, and No, in another sense.

Chao-chou seldom if ever repeated his answers to any question, however frequently it might be put to him. Not that he hankered after novelty, but that his single-hearted fidelity to the end—to pave the way to enlightenment for others—compelled him to use different answers in response to the exigencies of each case. Only such answers as these are living answers, flowing spontaneously from the heart. On the other hand, if you repeat the same answer to the same question, it becomes a dead formula, mechanically remembered and perfunctorily delivered. Even if the answer was original with you and had a wiggle of life in the beginning, your systematic repetition of it is liable to take all life out of it until it becomes as dead and dry as a sucked lemon. In this way, you easily degenerate from a speaker into a parrot.

It was by this test, I suppose, that Chao-chou is said to have exposed certain fakers. He had a keen nose for the counterfeits. Often clever neophytes came from famous centers of Ch’an south of the Yangtze river, after they had learned many a stock phrase and slogan from the lips of their masters. In their conversation with Chao-chou, they talked glibly of profound subjects and made frequent use of their masters’ words. Chao-chou called them “traveling peddlers.” When he was on the way to the Five-Story Mountain, he encountered a strange old woman. His fellow travellers had told him how she waited at the roadside and greeted every monk, and whenever a monk asked her to point the way to the monastery on the mountain, she would say, “Just go straight ahead!” And as the monk went his way, she would say, “So he passes on like this!” Many people suspected that she must be deeply versed in Ch’an. But Chao-chou said to them, “Let me try her out.” When he approached her, she greeted him as usual. When he asked her to point the way to the monastery, she answered, “Just go straight ahead!” As he was going his way, she said, “So he passes on like this!” Next day, he announced to his fellow travelers, “I have found her out!” “The spirit of Ch’an refuses to be stereotyped.

It was Chuang Tzu who said, “Only the True Man can have true knowledge.” Chao-chou was very much of the same mind, for he maintained that in the practice of Ch’an everything depends upon the person. He went to the extent of saying, “When the right person expounds a wrong doctrine, even the wrong doctrine becomes right. When the wrong person expounds a right doctrine, even the right doctrine becomes wrong.”

The wonderful thing about Chao-chou is that his advancing age did not tarnish the freshness of his mind. He was immune to senility. Few of his younger contemporaries could measure up to him in mental vigor. In his last years he already discerned certain signs of degeneration in the Ch’an tradition. “Ninety years ago,” he said, “I saw more than eighty enlightened masters in the lineage of Ma-tsu; all of them were creative spirits. Of late years, the pursuit of Ch’an has become more and more trivialized and ramified. Removed ever farther from the original spirit of men of supreme wisdom, the process of degeneration will go on from generation to generation.”

Assuming that these words were uttered in the last decade of the 9th century, when Chao-chou was in his 110s, we cannot but admit the accuracy of his observation. By that time the Golden Age of Ch’an was over. He had lived to be the last spiritual giant of the period of T’ang—the last, but not the least.

More About Chao-Chou

Chao-chou did not found a house of his own. He was too much of a freelancer to be interested in being an “ancestor” of brilliant descendents bearing his image and continuing his lineage. But all the “Five Houses” have drawn upon the “ancient Buddha of Chao-chou” as their common source of inspiration and wisdom. Therefore, I have collected some more anecdotes about him and some more wise saws from him, which appeal to me as typical expressions of the spirit of Ch’an.

1. Chao-chou and His Image

A monk had drawn a portrait of the master. When it was presented to him, he said, “If it is really a true image of me, then you can kill me. But if it is not, then you should burn it.”

2. “Lay It Down!”

A new arrival said apologetically to the master, “I have come here empty-handed!” “Lay it down then!” said the master. “Since I have brought nothing with me, what can I lay down?” asked the visitor. “Then go on carrying it!” said the master.

To be initiated into Ch’an, it is not enough to be emptyhanded. What is more important, you must be empty-hearted. To feel ashamed of your ignorance shows that your heart is still full of yourself.

3. Chao-chou’s Family Tradition

When a monk asked, “What is the Abbot’s family tradition?” the Abbot replied, “I have nothing inside, and I seek for nothing outside.”

4. The Beggar Lacks Nothing

A monk asked, “When a beggar comes, what shall we give him?” The master answered, “He is lacking in nothing.”

5. The True Man Not A Man

A monk asked, “Who is the man who finds no mate in the whole universe?” “He is not a man!” the master answered.

6. “Who Are You?”

A monk asked, “Who is the Buddha?” The master fired back, “Who are you?”

7. At a Funeral Procession

At the funeral of one of his monks, as the Abbot joined the procession, he remarked, “What a long procession of dead bodies follows the wake of a single living person!”

8. How Chao-Chou Laughed Over His Defeat

Nothing could be more interesting than to watch two great masters of Ch’an tease each other and pull each other’s legs. When Chao-chou visited the master Ta-tz’û, he asked the latter, “What can be the body (substratum) of Prajna?” Ta-tz’û just repeated the question, “Indeed, what can be the body of Prajna?” This time the ancient Buddha was caught, he had asked a senseless question! But instead of feeling embarrassed, he burst into a loud guffaw, and went out. The next morning, as he was sweeping the courtyard, Ta-tz’û chanced upon him, and, to tease him, asked, “What can be the body of Prajna?” Laying down the sweeper, Chao-chou laughed whole-heartedly and went away. Thereupon Ta-tz’û returned quietly to his room.

9. No Wisdom By Proxy

A monk besought him to tell him the most vitally important principle of Ch’an. The master excused himself by saying, “I must now go to make water. Think, even such a trifling thing I have to do in person!”

10. Ch’an as an Open Secret

A monk once asked him, “What is Chao-chou?” Obviously, he was not asking about the city of Chao-chou, but about the distinctive features of the master’s Ch’an. But the master answered him in terms of the city, “East gate, west gate, south gate, north gate.” His Ch’an is like an open city, which can be approached from all directions. There is nothing esoteric about his teaching. Every person with an ordinary mind can enter the city through any of its gates.

But this does not mean that the gates are always open. There is a time for opening the gates, and there is a time for closing them. When they are closed, it is said that no external force, not even the combined forces of the whole universe, can break through. Such then is Chao-chou’s Ch’an—an open secret!

Encounter Dialogues of Zhaozhou Congshen (778-897)

compiled by Satyavayu of Touching Earth Sangha

DOC: Treasury of the Forest of Ancestors

Great Master Zhaozhou Congshen was from Caozhou in the northern province of Shandong. He became a novice as a young boy at a local temple, and while still in his teens he became determined to practice under a Zen master. At seventeen he left his home region and traveled south, ending up in Anhui Province. When he heard about Master Nanquan Puyuan living in the mountains of the Chizhou region, Congshen went to seek him out. He found the master still living in his hermitage high on South Spring Mountain.

As he entered the master's room, Nanquan was lying down resting. The master asked, “Where have you come from?”

Congshen replied, “I've just been staying at Sacred Icon Temple.”

Nanquan asked, “Did you see the famous icon?”

Congshen said, “No, but I see a reclining buddha.”

Nanquan sat up and asked, “Are you a novice with a teacher, or none?”

Congshen replied, “I have a teacher.”

Nanquan asked, “Who is your teacher?”

Congshen said, “In the cold of this mid-winter, I am happy to see you enjoying good health, teacher.”

Master Nanquan then accepted Congshen as his student.

One day Congshen asked Master Nanquan, “What is the way?”

Nanquan said, “Ordinary mind is the way.”

Congshen asked, “Can I direct myself toward it?”

Nanquan said, “If you try to direct yourself towards it, you will be missing it.”

Congshen asked, “If I don't try, how can I know it?”

Nanquan said, “The way has nothing to do with knowing or not knowing. Knowing is just illusion, not knowing is blankness. When you enter the way beyond trying, it is like the great sky, vast and clear. How can we speak of affirming or negating?”

At these words, Congshen had a deep realization.

When Master Nanquan accepted an invitation to lead a new monastery at the base of the mountain, Congshen took on the role of head monk. He remained a devoted disciple of Nanquan for the rest of the master's life – some thirty more years. When the master passed away, Congshen was already fifty-seven.

At this point Congshen decided to embark on a life of homeless wandering. Declaring that he would be open to learning from a seven year old girl, or teaching an eighty year old master, he began to travel throughout central and northern China visiting numerous famous teachers, as well as secluded hermits, continually sharpening his insight and clarifying his expression. He remained a wandering pilgrim for the next twenty years.

One day Congshen went to visit a hermit. When he approached the hermit's cave he called out, “Are you there? Are you there?”

The hermit stepped out and held up his fist without saying a word.

Congshen said, “The water's too shallow here; not a place to drop anchor.” Then he left.

Later he went to visit another hermit, and again called out, “Are you there? Are you there?'

This hermit came out and also just held up a fist. Congshen said, “You have the power to give and take away, to kill and to give life.” Then he bowed and went away.

Once Congshen went to visit the young teacher Daoying at his hermitage. Daoying said to him, “Great Elder, why don't you look for a place to settle down?”

Congshen replied, “What is the place where this person could dwell?”

Daoying said, “In front of this mountain there is the foundation of an ancient temple.”

Congshen said, “Honored priest, it would be good for you to live there yourself.”

Eventually, at the age of eighty, Congshen decided to rest his feet at a small, rundown temple in the city of Zhaozhou, in the northern province of Hebei. In this humble residence named after the bodhisattva of compassion Guanyin (Observing Sound), the master spent the rest of his life teaching a small community, and receiving a steady stream of guests. Turning down offers of expansion or improvement to his temple, the residents often numbered less than twenty. Unimpressed with wealth and social standing, when government officials came to visit, the master often remained in his seat, and when common folk came he was known to go out and meet them at the gate. As his reputation spread throughout the rest of his long life, countless pilgrims made their way to his northern outpost to receive his teaching.

Once Master Zhaozhou Congshen entered the hall and said to the assembly:

“Practitioners, if someone comes from the south, I unburden them; if someone comes from the north, I load them up. If you go to the one unburdened and ask about the way, you will lose the way. If you go to the one loaded up and ask about the way, you will gain the way.

“Practitioners, if a true person speaks a mistaken teaching, even the mistaken teaching becomes correct. If a false person speaks the correct teaching, even the correct teaching becomes false.

“At other places it's difficult to understand, but easy to embody. At this place it's easy to understand but difficult to embody.”

The master also said, “The essential matter is like a bright jewel in the palm of your hand. When a foreigner comes, a foreigner appears; when a local comes, a local appears.

“This old monk takes a blade of grass and makes it into the sixteen foot golden body of the Buddha. I also take the sixteen foot golden body and make it into a blade of grass. The Awakened One

is delusion, delusions are the awakened one.”

Then a monk came forward and asked, “For whom is the Awakened One a delusion?”

Master Zhaozhou said, “It's the delusion of everybody.”

The monk asked, “How can we get rid of it?”

The master said, “Why should we get rid of it?”

Once Master Zhaozhou addressed the assembly saying, “I don't like to hear the word 'buddha.'”

A monk came forward and asked, “Then how does the master teach others?”

The master said, “buddha, buddha.”

Once a monk asked Master Zhaozhou, “What is Buddha?'

The master said, “The one on the altar.”

The monk said, “But isn't the one on the altar just a clay figure, made from mud?”

The master said, “Yes, that's right.”

The monk asked, “Then what is Buddha?”

The master said, “The one on the altar.”

Another time a monk asked Master Zhaozhou, “What is the meaning of Bodhidharma coming from India?”

The master said, “The cypress tree here in the garden.”

The monk said, “Master, please don't teach me just using an object.”

The master said, “I'm not teaching using an object.”

The monk then asked again, “What is the meaning of Bodhidharma coming from India?”

The master said, “The cypress tree here in the garden.”

One day a monk asked Master Zhaozhou, “Before there was this world, already there was original nature. When this world is destroyed, this nature will not be destroyed. What is this indestructible nature?”

The master said, “The four great elements and the five skandhas.”

The monk replied, “These will also be destroyed. What is the indestructible nature?”

The master said, “The four great elements and the five skandhas.”

Once a monk asked Master Zhaozhou, “Does a dog have awakened nature?”

The master said, “Yes.”

The monk said, “If so, why does it enter into this difficult embodied life?”

The master said, “Although it knows, it intentionally transgresses.”

Another time a monk asked, “Does a dog have awakened nature?”

The master said, “No.”

The monk said, “But we've been taught that all living beings have Awakened Nature – why do you say that a dog doesn't have it?”

The master said, “Because of habitual conditioning.”

One day Master Zhaozhou asked a newly arrived monk, “Have you been here before?”

The monk said, “Yes, I've been here.”

The master said, “Have a cup of tea.”

Later he asked another monk, “Have you been here before?”

The monk said, “No, I've never been here.”

The master said, “Have a cup of tea.”

Then the temple director asked the master, “Why did you say 'Have a cup of tea' to the one who had not been here, as well as to the one who had?'

The master said, “Director!”

The director said, “Yes?”

The master said, “Have a cup of tea.”

Once a monk said to Master Zhaozhou, “I've just entered the community here – please, master, give me some instruction.”

The master asked, “Have you eaten breakfast?”

The monk said, “Yes, I've eaten.”

The master said, “Then wash your bowls.”

The monk had a deep realization.

In the city of Zhaozhou is a famous stone bridge of great antiquity. Once a monk came to see Master Zhaozhou and said, “For a long time I've heard of the stone bridge of Zhaozhou, but so far I've only seen a simple wooden bridge.”

The master said, “You've only seen the wooden bridge. You haven't seen the stone bridge.”

The monk asked, “What's the stone bridge like?”

The master said, “Donkeys cross, horses cross.”

One day when Master Zhaozhou was wandering around town, he came across an old woman he knew carrying a basket. He immediately asked, “Where are you going?”

The old woman said, “I'm on my way to steal Master Zhaozhou's bamboo shoots.”

Zhaozhou asked, “What will you do if you run into Master Zhaozhou?”

The old woman came up to the master and gave him a slap.

Once a messenger came to see Master Zhaozhou with a donation from an old woman who requested that the master perform the ritual of “rotating” the scriptures. The master got down from his seat, walked in a circle around the sitting platform, and then said to the messenger, “I have finished rotating the great scriptures.”

The messenger returned to the old woman and told her what happened. She said, “I asked him to rotate the entire canon of scriptures. How come the master rotated only half the cannon?”

A nun once asked Master Zhaozhou, “What is the deeply secret heart?”

Zhaozhou took her hand and squeezed it.

The nun said, “Do you still have that in you?”

Zhaozhou said, “You have it, too.”

One day when Master Zhaozhou was sweeping, a visiting layman said, “You are a great Zen Master – why are you sweeping?”

The master said, “Dust comes in from outside.”

The man said, “This is a pure temple. Why is there dust?”

The master said, “Here comes some more!”

Once Master Zhaozhou's disciple Shanxin asked the master, “What do you do when nothing comes up?”

The master said, “Put it down.”

Shanxin said, “When there's nothing that is coming up, how can you put it down?”

The master said, “Then carry it away.”

Shanxin had a deep insight.

One day a monk asked, “How should we employ our minds throughout the twenty-four hours?”

Master Zhaozhou said, “You are used by the twenty-four hours; this old monk can use the twenty-four hours. Which twenty-four hours are you asking about?”

Once Master Zhaozhou addressed the community saying, “'The great way is not difficult, just avoid picking and choosing.' As soon as words are present, there is choosing, and there is thinking. It's not to be found in thinking. Is thinking what you're upholding and sustaining?”

A monk came forward and asked, “Since it's not found in thinking, what should we uphold and sustain?”

The master said, “Don't know.”

The monk continued, “Since the master doesn't know, how can you be sure it isn't within thinking?”

The master said, “Ask and you have an answer. Then bow and withdraw.”

One day a monk came to bid farewell to Master Zhaozhou. The master asked, “Where are you going?”

The monk said, “I'm going to visit various places to study the way of awakening.”

Zhaozhou said, “Be careful not to get stuck in a place where there is an awakened one. And quickly pass by a place where there is no awakened one. Whomever you meet, be sure not to misguide them.”

After a pause the monk said, “Hearing that, I think I'll just stay here.”

The master said, “Then go pick up the willow blossoms.”

The city of Zhaozhou was close to the famous Buddhist pilgrimage site of Wutai Mountain. Along the pilgrimage route, many monks encountered an old woman who, whenever she was asked the way to the mountain, would always say, “Just go straight ahead.” Then when the monk would walk on, she would always remark, “Another good monk goes off like that.”

Eventually one of the monks told Master Zhaozhou about it. The master said, “Wait for a while, and I'll go and check her out.”

The next day the master found the old woman on the road and asked, “Which way is the road to Wutai Mountain?”

The woman said, “Just go straight ahead.” Then, as the master walked on, she said, “Another good monk goes off like that.”

The master returned to the temple and said to the community, “I've checked out that old woman for you.”

Once a monk asked Master Zhaozhou, “What is the road without mistakes?”

The master said, “Clarifying mind, seeing nature; that's the road without mistakes.”

Shexian Guisheng said:

If someone asked me “what is the road without mistakes?”, I would tell them,

The inner gate of every house extends to Eternal Peace (Chang'an, the capital).

Once a monk who had stayed at Xuefeng Monastery in the south came to see Master Zhaozhou. Master Xeufeng Yicun, the teacher at this monastery, had risen to great prominence in his region. Master Zhaozhou asked the monk, “What is Master Xeufeng teaching these days?”

The monk reported that Xeufeng had said, “The whole world is the eye of a practitioner. Where will you take a shit?”

Master Zhaozhou replied, “If you return to Xeufeng, you should take a trowel.”

Once a visiting official asked Master Zhaozhou, “Is the master able to enter into the hell realms?”

The master said, “I entered the hell realms long ago.”

The official asked, “Why did you, a great Zen master, enter into hell?”

The master said, “If I didn't enter into hell, who would teach you?”

One day a monk asked Master Zhaozhou, “The ten thousand things all return to the one. To where does the one return?”

The master replied, “Back when I lived in Qingzhou I made a hemp robe that weighed seven pounds.”

Eventually, at the age of 120, Master Zhaozhou lay down on his right side and passed away. A layman had once asked the master how old he was, and the master had replied, “There are numberless beads on the string of a rosary.”

ZEN DEBATES

http://global.sotozen-net.or.jp/eng/library/stories/book3.html

In the ninth century, during the Tang Dynasty, there was an excellent Zen master named Zhaozhou (Joshu, in Japanese). One day a monk named Yanyang (Gon'yo, in Japanese) asked him, “I have come with nothing. What do I do in such a case?”

Zhaozhou replied, “Throw it away.” On the surface, this was not an answer. Then Yanyang asked as though cross examining, “I said I came with nothing, so what do you expect me to throw away?”

Zhaozhou promptly said, “Then hurry and take it away.” This was even a stranger answer than the previous one. Zen debates are strange, and a certain storyteller made a comedy out of one:

One day a monk on pilgrimage came to the front of a mountain temple and shouted, “Hello! Is the head priest here? I want to have a debate with him.” A novice priest came out of the temple and shouted back even louder, “First let's you and I have a debate, and if you beat me then I'll call the head priest.”

“Why you impudent little … all right,” and the traveling monk silently extended his right hand and made a circle with his thumb and index finger.

The boy immediately made a larger circle with his arms.

The traveling monk held up one finger.

The boy responded by raising five fingers.

The pilgrim monk then raised three fingers which the boy countered by making a face. As though beaten, the pilgrim hurriedly ran away.

The head priest had witnessed this question and answer session through a crack in the door, and he was surprised. He was surprised because he interpreted the dialogue as follows. The circle made by the traveling monk meant “What is your mind?”

In response to this the boy had made a large circle which meant “Like an ocean”, and this was a splendid answer. The one finger raised by the pilgrim meant “How about your body?” In reply the novice priest had raised five fingers, which signified the five Buddhist precepts ― no killing, no stealing, no adultery, no lying and no drinking. This again was a suitable answer. The pilgrim's raising of three fingers represented the three great worlds which make up the entire universe, and the boy's making a face meant “It is in front of my eyes.”

The head priest who had interpreted the debate in this way thought, “How strange. The boy can't have that much ability, can he?” Calling out to the acolyte he asked, “What were you doing there?”

“The traveling monk must have heard that I was the son of a mochi (rice cake) dealer.”

“Why?”

“Because he made a small circle to say that my father's rice cakes are small. That's why I made a larger circle to show that they're big. Then he asked how much one costs, and I told him five pennies. And he wanted me to discount the price to three pennies, so I made a face. He must not have had any money because he ran away.”

The head priest burst out laughing. This dialogue is opposite that of the one before. Even though the form is the same, the content is incoherent.

Now, returning to the original story ― Yanyang said, “I have nothing.” In other words, “I have attained ‘satori' (enlightenment) egolessness, and ‘no mind'.” However, from Zhaozhou's point of view, Yanyang had too much. ‘If you have one thing on your mind, you have a heavy load on your back.' And Yanyang was carrying around a heavy load which he called “having nothing”.

When one is really healthy he forgets his good health. A drinker may say, “I've had enough, I've had enough,” but as long as he keeps the glass in his hand he hasn't had enough. If he really had enough, he would put the glass down.

That is why Zhaozhou said, “Throw it away,” and urged Yanyang to take one more step off the top of the hundred foot bamboo pole to truly attain enlightenment, but Yanyang did not understand this. He retorted, “I said I had nothing, so how can I throw anything away?” Here, finally, his pride in not ‘having anything' came out. And this is why Zhaozhou said, “Then, take it with you.”

Zhaozhou Meets A Nun

尼到趙州問密密意, 趙州探其穴, 尼曰: 「 和尚還有者個? 」 趙州曰: 「 某無者個; 汝卻有者個。 」

禪 海 塔 燈 http://www.yogichen.org/cw/cw13/cw13_3.pdf p. 144.Some koans as presented in Yogi Chen's original book may be different from other known versions.

A nun came to Zhao Zhou and asked about the most secret meaning.

Zhao Zhou poked at her genital.

The nun said, "Monk still has this?"

Zhao Zhou said, "One does not have this one; and yet you have this one."

Translated by Dr. Yutang Lin (Lin Yutang 林 钰堂)

A nun came to Chao Chou and asked about the secret teaching.

Chao Chou felt her vagina.

The nun said, ”Does your Reverence have this?”

Chao Chou said, ”I do not have this, but you have it.”

Translated by Dr. Fa-yen Kog ( 顧法嚴 / 顾法严 Ku, Fa-yen / Gu Fayan, 1917-?)

Yogi Chen's "The Lighthouse in the Ocean of Chan" was translated decades ago by Dr. Fa-Yen Kog, p. 110.

尼到趙州問密密意。趙州伸手便探其穴。尼曰: “ 和尚還有這個! ” 趙州曰: “ 某無這個,汝卻有這個。

A nun asked, "What is the innermost mind?"

Joshu pinched the nun's hand.

The nun said, "Master, you are still that way, aren't you?"

Joshu said, "It is you who are that way."

Translated by Yoel Hoffmann, No. 283.

A nun asked, "What is the deeply secret mind?"

The master squeezed her hand.

The nun said, ”Do you still have that in you?”*

The master said, ”It is you who have it.”

*”Are you still attached to that?”

Translated by James Green, No. 319.