SZÓTÓ ZEN SŌTŌ ZEN

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

應量器/応量器 Ōryōki

(Sanskrit:) pātra

(English:) alms bowl; begging bowl; (“just enough”)

(Magyar:) kolduscsésze; („épp elegendő”)

Also called 鉢 hachi, 宝鉢, hōbachi or iron bowl (鉄鉢 teppatsu; 応量器展鉢 oryoki tenpatsu) or Buddha bowl (仏鉢 buppatsu).

Literally a "vessel" (ki 器) that contains an "appropriate amount" (ōryō 應量) of food. In India, Buddhist monks carried a bowl (S. pātra) when soliciting alms food from the laity that was supposed to be large enough to hold a nourishing meal but small enough to prevent gluttony. The bowl was one of the few personal possessions allowed a Buddhist monk. It was received upon ordination as a novice monk and was, together with the patchwork ochre robe (S. kāṣāya ), emblematic of membership in the monastic order. As Buddhism evolved in India, it became the accepted norm for monasteries to have stores of food, kitchens, and dining halls for communal meals, but the bowl (or set of bowls) in which the meal was received and eaten remained the personal property of individual monks. In Soto Zen today, monks receive a set of nested bowls (made of lacquered wood) upon ordination and use them for formal meals when residing in training monasteries.

A bowl used by Buddhist monks for meals, and as a begging bowl. The hachi is rounded and deep, with no foot ring. It is most frequently made from lacquered wood, iron teppatsu 鉄鉢,or pottery, but there are also examples made from stone, gilt bronze, silver, and porcelain. According to ancient Buddhist law, a monk's only possessions should be three robes and one iron bowl sanne ippatsu 三衣一鉢. If the bowl gets broken it may be repaired up to five times and re-used; souryo no teppatsu wa gotetsu 僧侶の鉄鉢は五綴. The word gotetsu is also used to refer to a monk's bowl.

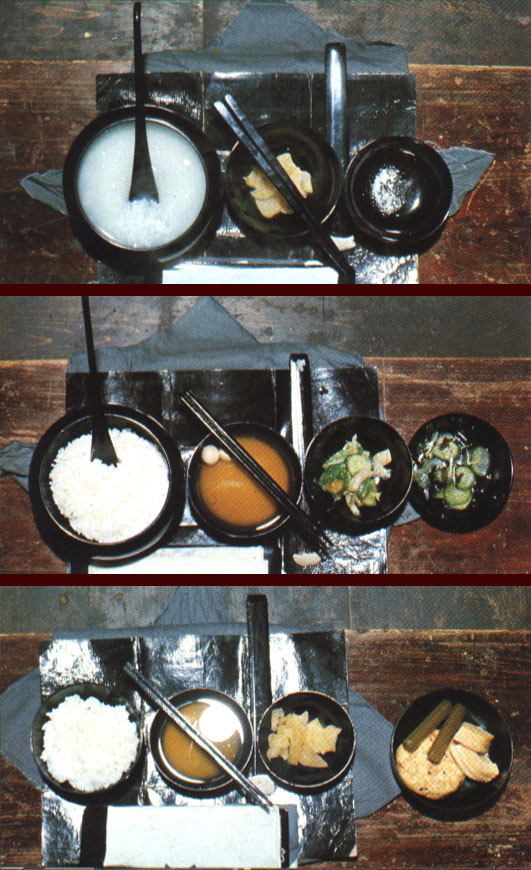

a 4 szótó evőcsésze

a 4 szótó evőcsésze

The Sôtô 4 bowls set (応量器 ôryôki)

Rice bowl, juice bowl, first side-dish bowl, second side-dish bowl

az 5 rinzai evőcsésze

az 5 rinzai evőcsésze

臨済宗用木質応量器 (黒塗5点組) The standard Rinzai 5 bowls set (持鉢 jihatsu)

[黄檗宗では 3 枚; Obaku sect: 3 bowls]

tálalás

tálalás

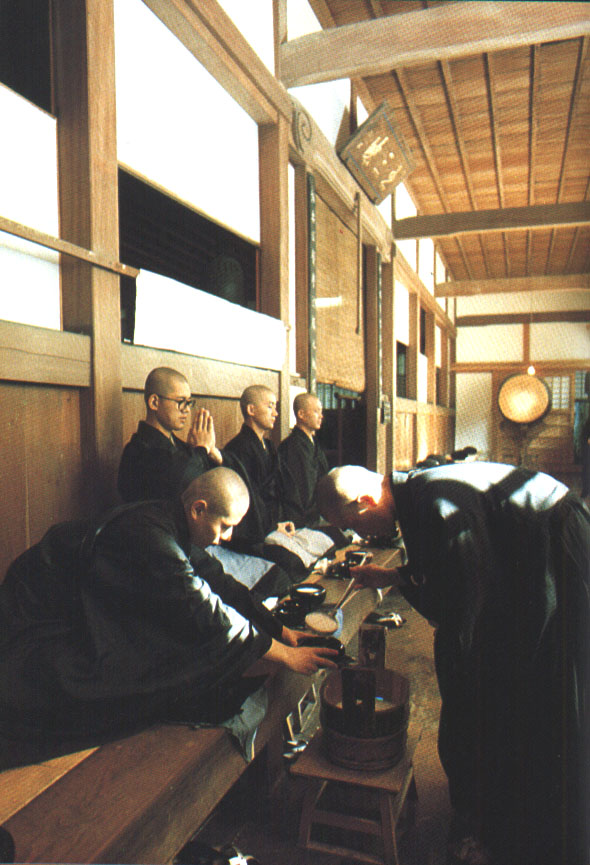

Expressing gratitude for the food

reggeli, ebéd, vacsora

reggeli, ebéd, vacsora

The meals of monks in training: morning meal, noon meal, evening meal

1) morning gruel (chōshuku 朝粥) [= 小食 shōjiki; 粥坐 shukuza; 赴粥 fushuku]

Rice gruel (shuku 粥), a porridge made by boiling rice until the kernels have mostly disintegrated, was the standard breakfast fare in Chinese Buddhist monasteries of the Song and Yuan dynasties and the medieval Japanese Zen monasteries that were modeled after them. It continues to be served for breakfast at Japanese Zen monasteries today.2) midday main meal (齋 sai) [= 中食 chūjiki]

3) evening meal (yakuseki kittō 藥石喫湯, yakuseki 藥石)

Literally "medicine" (yakuseki 藥石) and "drinking decoctions" (kittō 喫湯). According to the Indian Vinaya, Buddhist monks were not permitted to take solid food after midday, but drinking liquids was allowed. For monks who were ill, however, solid food was permitted at any time of day for medicinal purposes. In the Chinese Buddhist monasteries of the Song and Yuan dynasties that served as the model for Japanese Zen monasteries, an evening meal was routinely served to all the monks in residence, but it was euphemistically called "medicine."

PDF: Ōryōki : a Manual for the Construction and Use of Eating Bowls > 2nd ed.

Pamphlet by Les Kaye

Kannon Do Zen Center, 1975, 45 pages

Eating Just The Right Amount

by John Kain

http://www.tricycle.com/feature/eating-just-right-amount

The ancient Japanese mealtime art of oryoki reveals the patterns and sticking points of our minds.

Oryoki, often translated as “just the right amount,” is a highly choreographed ritual of serving and eating food—a ceremonial dance of giving, receiving, and appreciation. It is a practice that was codified in China during the T'ang dynasty and was the model for the sweeping grace of the tea ceremony. Practiced, with a few variations, throughout the Zen schools, it was also adopted—in America—by Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, the Tibetan founder of the Shambhala lineage. Practically speaking, it is perhaps the most efficient, aesthetically pleasing, and least wasteful way to feed a large group of people sitting in a meditation hall, or a single person at home for that matter. Yet more specifically—and arising from Zen's insistence on blending the sacred and the mundane—oryoki unifies daily life and “spiritual practice.” It is essentially a state of mind, a way of being.

Oryoki practice uses a jihatsu, a set of nested bowls: a Buddha bowl, or zuhatsu, containing three or four smaller bowls tied in cloth with a topknot resembling a lotus flower. The set also contains—in a narrow cloth pouch—a wooden spoon, a pair of chopsticks, and a small spatula-like utensil called a setsu, which is used to clean the bowls. The outer cloth, when untied and refolded in an exact manner, doubles as a place mat upon which the bowls are laid in a prescribed sequence. To complete the package, there is a regular-sized cloth napkin and a smaller cleaning towel used to wipe the bowls dry after they are filled with hot tea or water and scraped clean with the setsu.

Participants sit in a meditation posture and wait to offer their empty bowls as the servers bring food and, in a series of hand gestures (beyond the chants of dedication and appreciation, oryoki is practiced in silence), fill the bowls to the requested level. The ecology of oryoki is complete: there is no waste. Participants are urged to take just the right amount of food—not a crumb should remain. The cleaning liquid, after it is used to wash each bowl, is partially drunk and the remainder collected and distributed in the garden. Each movement of oryoki is compact, subtle, and designed to unfold in harmony, demanding meticulous awareness to what is happening in the moment.

ŌRYŌKI

The practice of the Eating Bowl

The text was copied from the White Wind Zen Community Website at http://www.wwzc.org

Cf.

http://global.sotozen-net.or.jp/eng/practice/eating/oryoki/

The eating bowls now in use in Zen monasteries have been used by monks in China and Japan for over one thousand years. Called "ooryooki", these bowls are part of Buddhist traditions of giving and non-attachment.

In Japanese, the word OORYOOKI is comprised of three symbols:

OO, the receiver's response to the offering of food

RYOO, a measure, or an amount, to be received

KI, the bowl

The term OORYOOKI includes not just the food-carrying vehicle, but the practice and giving of the recipient.

In early Buddhist tradition, it was the usual practice for monks to obtain their daily food by begging. Actually, begging existed before Buddha's time,being practiced by many religious sects. However,the idea took on a larger meaning in Buddhism, where begging became an act of "offering", an exchange between monks and laymen in general.

Wooden OORYOOKI bowls of today are like those developed in the monastic community of Hui Neng. The large bow is shaped like Buddha's own head, symbolizing wisdom. It is totally rounded, that is does not have a flat spot to rest on, but must be supported by a small stand when not being held. The spoon, stick, "setsu", and "hattan" were also developed in Chinese Zen Monasteries.

Since Hui-Neng, all monks receive a robe and bowl from their teacher. Whether we are monk or layman, when we use OORYOOKI we are sharing equally in the truth transmitted from Buddha to each of us.

Buddhist tradition has emphasized the monk's robe and bowl as symbolic of the two things most necessary to sustain life: with one, we are supported externally (clothes, shelter), with the other ,internally (food). In early Buddhism, transmission of the robe and bowl was an important aspect of maintaining the line of patriarchal succession. In this regard, the items were symbolic of Buddha and by using them, the patriarch was emphasizing Buddha's uninterrupted existence.

The present day OORYOOKI used by Zen monks consists of following items:

|

|

(袈裟行李 kesagōri)

(袈裟行李 kesagōri)

In a monastery, where students have assigned cushions, it is customary to keep ooryooki on the "kanki", chest in the Sodo. Washing is done on the "off" day (days with a 4 and 9). On these days, monks are given time to attend to personal items, such as laundry, shaving, etc.

Replace setsu tip when it becomes very soiled. In the monasteries, it is the usual practice to replace the tip before sesshin.

|

1. Place ooryooki directly in front of you with the tied corners of the folding cloth pointing toward your right.

|

|

4. Drying Cloth

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Utensil Holder and Water Board

|

|

6. Napkin

|

|

|

|

|

7. Folding cloth

|

|

|

|

|

8. Hattan 鉢単

|

|

|

|

|

9. Bowls

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10. Utensils

|

|

Zen Meal Sutras

The Buddha, born at Kapilavastu,

Attained the way at Magadha, preached at Varanasi,

Entered Nirvana at Kusinagara.

Now as we spread the bowls of Buddha Tathagatha

We make our vows together with all beings.

We and this food and our eating are empty.

Nyan ni san bo

An su in shi

Nyan pin dai shu nyan

Vairochana, pure and clear Dharmakaya Buddha;

Lochana, full and complete Sambogakaya Buddha;

Shakyamuni, infinitely varied Nirmanakaya Buddha;

Maitreya, Buddha still to be born;

All Buddhas everywhere, past, present, future;

Mahayana, lotus of the subtle law;

Manjusri, great wisdom Bodhisattva;

Samantabhadra, Mahayana Bodhisattva;

Avalokitesvara, Great compassion Bodhisattva;

All venerated Bodhisattvas, Mahasattvas,

The great Prajna Paramita.

Porridge is effective in ten ways

To aid the student of Zen.

No limit to the good result,

Consummating eternal happiness.

...

These three virtues and six flavours

Are offered to the Buddha and Sangha

May all beings of the universe

Share alike this nourishment.

...

First, we consider in detail the merit of this food and remember how it came to us;

Second, we evaluate our own virtue and practice, lacking or complete, as we receive this offering;

Third, we are careful about greed, hatred and ignorance, to guard our minds and to free ourselves from error;

Fourth, we take this good medicine to save our bodies from emaciation;

Fifth, we accept this food to achieve the Way of the Buddha.

...

Oh, all you demons and spirits,

We now offer this food to you.

May all of you everywhere

Share it with us together.

...

The first portion is for the Three Treasures,

The second is for the Four Blessings;

The third is for the Six Paths;

Together with all we take this food.

The first taste is to cut off all evil,

The second is to practice all good,

The third is to save all beings;

May we all attain the Way of the Buddha.

...

We wash our bowls in this water,

It has the flavour of ambrosial dew.

We offer it to all demons and spirits;

May all be filled and satisfied.

OM MAKULASAI SVAHA

...

The world is like an empty sky,

The lotus does not adhere to water.

Our minds, surpassing that in purity,

We bow in veneratlon to thee most Exalted One.

典座教訓 Tenzo kyōkun

by [永平] 道元 希玄 [Eihei] Dōgen Kigen (1200-1253)

Instructions for the Cook Translated by Griffith Foulk

Instructions for the Tenzo Tr. by Anzan Hoshin & Yasuda Joshu Dainen

PDF: Kaiseki: Zen tastes in Japanese cooking

by Kaichi Tsuji

Foreword by Yasunari Kawabata

1972