SZÓTÓ ZEN SŌTŌ ZEN

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

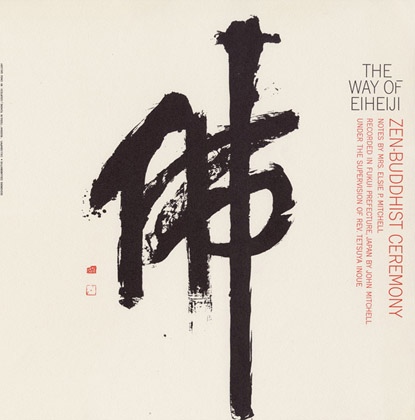

Cover illustration calligraphy of "Buddha" by Tsoulin Tcheng, courtesy of Mi Chou Gallery

The Way of Eiheiji: Zen-Buddhist Ceremony

Originally issued as analog disc

on Folkways Records: FR 8980,

New York, 1959. (2xLP + box;

p. 4 s. 12 in. 33 1/3 rpm. microgroove)

Compact disc: Smithsonian Folkways, 2000.

Includes explanatory notes by Elsie P. Mitchell

(1926-2011), text of the ceremonies in Japanese (transliterated) with English translations, and glossary ([16] p.).

Recorded in the Eiheiji, Fukui Prefecture, Japan, 1957, by John Mitchell (d. 1994); under the supervision of Rev.

井上哲也 Inoue Tetsuya

(1929-1997)

Translating: S. Ihara, C. Horioka, T. Inoue, D. Katagiri, K. Matsunami, S. Ichimura

Read about the creation of these recordings in an article on Elsie Mitchell, Cambridge Buddhist Trailblazer by David Chadwick - November 2002

Track Information:

| 101. Time-Telling Drum and Gong (Koten). |

| 101. Hand Bell. |

| 101. Meditation Bell (Kyosho). |

| 101. Metal Gong (Dai Kaijo) and Small Board. |

| 101. Sodo Bell (Nairansho). |

| 101. Verse for Putting on Kesa (Takkesa-Ge). |

| 101. Morning Ceremony. |

| 101. Hannya Shingyo (Chant). |

| 101. San Do Kai (Chant). |

| 101. Eko (Chant). |

| 101. Juryobonge (Chant). |

| 201. Breakfast Preparation Bells and Gongs. |

| 201. Eating Verses (Jikiji-Ho). |

| 201. Dai Rai Drum. |

| 201. Densho Drum. |

| 201. Dai Hi Shin Dharani (Recitation). |

| 201. Ryaku Fusatsu Ceremony. |

| 201. Midday Service in Butsuden. |

| 301. Fire Protection Ceremony. |

| 301. Dai Hi Shin Dharani (With Eko and Refrain). |

| 301. Interview of Novice. |

| 301. Shomyo Chant. |

| 301. Jikiji-Ho Chant. |

| 301. Densho and Inkin. |

| 301. Mokugyo. |

| 301. Dharani Prayer and Refrain. |

| 401. Evening Ceremony. |

| 401. Memorial Service for the Dead (Segaki). |

| 401. Kanromon (Gate of Immortality). |

| 401. Shushogi (Taking Vows). |

| 401. Konsho (Evening Bell). |

| 401. Myohorengekyo Fumonbonge (Chant). |

| 401. Jiho Sanshi (Close of Ceremony). |

| 401. Hatto Bell and Keisu. |

The Booklet from

The Way of Eiheiji: Zen-Buddhist Ceremony

by Mrs. Elsie P. Mitchell

Revised Edition by G. Terebess

Cf. http://media.smithsonianfolkways.org/liner_notes/folkways/FW08980.pdf

http://www.cuke.com/bibliography/WOE/text.html

http://www.cuke.com/bibliography/WOE/sutras.html

http://www.cuke.com/bibliography/WOE/glossary.html

The Eiheiji (temple of Great Peace) is located in the mountains of Fukui Prefecture about six hours train ride from the old capital of Kyoto. This temple was founded in 1244 by

Dōgen Zenji, one of the outstanding personalities of Japanese Buddhism and one of Japan's great philosophers. He was born in the year 1200 of aristocratic parents. At the age of nine he is said to have read the Chinese translation of Vasubandhu's Abhidharma-kosa-sastra (a Sanskrit text of 30 volumes) and at 14 to have been ordained at the Hiei Monastery in Kyoto. After some years of study in the temples of Kyoto, he felt the need of a new master and left Japan for China where he finally became the disciple of the Zen monk, Ju-tsing. Under this master he found what he was looking for, and then returned to his own country where he established a temple in the vicinity of Kyoto. However, the proximity to Kyoto had many disadvantages and wishing to avoid political involvement, Dōgen founded a new temple in remote Echizen no kuni, now Fukui Prefecture. He remained in his Eihei Temple for the rest of his life instructing his disciples and writing prolifically. In his last years the Emperor Gosaga wished to present him with a purple robe. Dōgen refused to accept the gift until his relatives in Kyoto, fearing imperial displeasure, finally persuaded him to change his mind. He is said never to have worn the symbol of royal favor: "laughed at by monkeys and cranes, an old man in purple robes."

Eiheiji is now one of the two [large] training centers for priests and ordained laymen of the Sōtō Zen sect of Buddhism. The temple is perched on the side of a mountain and surrounded by giant cryptomeria. In winter it is engulfed in 6 or 7 feet of snow. The sun is rarely seen for a whole day at any time of the year; heavy fog and rain drift up from the Japan Sea. The rocks and the black trunks of the cryptomeria are covered with heavy dark green moss and the temple compound is blanketed with this flourishing vegetation. The monks tend it carefully, weeding out small plants and grass. From April till early December the sound of rushing water can be heard throughout the temple compound through which flow a number of mountain streams that break and fall just below the main entrance. Eiheiji comprises 14 large buildings as well as guest quarters and numerous smaller buildings. These are joined by long covered passages. The floors of these passages are so highly polished that one must take great care not to fall as one pads up and down the endless stairs in floppy felt slippers. Monks and guests all leave their shoes in a small building next to the main gate.

Inside the sammon (main gate) are two tall plaques bearing characters which mean: "only those concerned with the problem of life and death should enter here. Those not completely concerned with this problem have no reason to pass this gate." In the spring and in the autumn, those who wish to be accepted as novices, arrive in their traditional costume which includes a big bamboo hat, a short, full skirted black robe and white leggings. An applicant first prostrates himself three times and then announces his arrival by whacking a small wooden gong with a wooden mallet. He is first led to a small room (in the sappir) where he is told to sit in the cross legged position called the lotus position. Here he must remain until one of the senior monks comes to interview him 6 or 7 hours later.

"Why have you come to this temple?" one young novice is asked. "To meet the founder (Dōgen) face to face" (to learn his teaching) replies the novice. Then he is asked, "how should this be done?" "I think by forgetting oneself," he replies. Then he is asked, "What was written inside the sammon?" The novice cannot remember and the senior monk asks, "do you always enter places when you don't know what lies within? --- The founder's teachings can be studied in your home temple; to take the trouble to come here to this main temple was unnecessary. Those who do not see and comprehend what is written inside the sammon cannot understand the teaching. To learn about Buddhism is to learn about oneself, to learn about oneself is to forget oneself."

Another applicant is asked, "why didn't you come here sooner?" "I had business to take care of and my father was sick," replies the novice. "I am waiting to hear the reason," is the sharp reply.

A third novice, when asked for his reason for coming, answers, "I wish to receive the training of this temple." "There is none of that kind of training here," he is told and he is taken by the scruff of the neck and put out of the room.

"Daily life is none other than the way." The novice's first task after his interview may be to wash the lavatory floor. After a gasshō (palms joined in the attitude of prayer and head bowed), before the small shrine near the entrance, he ties up his long sleeves, dons wooden geta (a kind of wooden sandal) and proceeds to wash up as quickly and efficiently as possible under the watchful eye of the senior monk. This task preceded by the gesture of gasshō is a more significant part of the monk's life than any of the colorful and impressive ceremonies performed in the temple. In the gasshō the left hand symbolizes the heart (Buddha nature) of the greeter or one venerating, and the right hand thsze greeted or venerated. Monks greet each other and guests; and venerate the Buddha's images in this way. At Eiheiji the gasshō is also please, thank you and excuse me. It is used by the monks before many of the most menial of their tasks in the spirit of the Chinese Zen poet P'ang-yun, "Miraculous power and marvelous activity— Drawing water and hewing wood!" The gasshō is truly an attitude towards life. When this gesture is made quite spontaneously and automatically before a hot bath or a cup of tea; before going to the toilet; in time of pain or sorrow, then the way of the Buddha has taken its first step beyond philosophy.

2

________________________________________

The samu (manual labor) of the Eiheiji monk is not a mortification. It is not a disagreeable, but a necessary means to a desirable end. Samu combined withzazen (meditation in the cross legged position) stimulates an omnipresent WHY which is the center of Zen life. The answer to this WHY cannot be grasped by logic; it cannot be apprehended through ritual and the Zen master cannot give his disciples the answer.

He can only help them to find it for themselves. When a Zen monk knows the answer to the Zen question, as he knows his own breathing; when he has become the answer itself, his temple and his master have no more to teach him.

In Rinzai Zen which was introduced to the West by Dr. Suzuki, the Zen master helps his disciples to answer this WHY by posing koans or problems which cannot be solved by reason. As, for example, "who were you before your father and mother conceived you?" These koans are meditated on during zazen. The koan is not used in this way at Eiheiji. Rinzai koans are usually taken from the Japanese or Chinese classics. The Sōtō koan is life itself. Sōtō zazen is called kufū zazen, or the zazen in which one struggles by oneself.

The Eiheiji Zen master is always available and ready to answer the monk's questions (sanshi-mompō). However, the answers of the master are not a source of comfort but of frustration. A typical response is a pleasant smile and the reply, "be grateful." Ordinarily gratitude means appreciation for benefits received. However, the Zen master's "grateful" is not gratitude for any special thing or things. It is based not on discrimination but on awareness. The monk's regime is oriented to stimulate this awareness. Many small details of everyday life, which ordinarily are so automatic that they have no experiential content, are formalized or ritualized and long hours of sitting in zazen provide plenty of opportunity to become thoroughly aware of the interrelationship of mind and body, the self and others, humanity and other forms of life, active or quiescent.

The Rinzai masters, for very good psychological reasons, tend to hustle their followers beyond value judgments in order to achieve the desired end of a satori (enlightenment) experience. For equally good psychological reasons, Dōgen decided that the means being inherent in the end, the developing awareness which is not shared spontaneously is not a Buddhist form of Zen (more strictly speaking, not a Mahayana form of Zen).

It is difficult for Westerners to understand the function of ritual in such a system. A British Buddhist has suggested that perhaps chanting puts one in the mood for Satori.

Chanting is not only an expression of the pleasure of zazen but it also contributes to this same pleasure. zazen at first, is a difficult physical, emotional and mental discipline. However, as the ego relaxes its machinations, the practice becomes pleasure itself. In order to chant well, one must breathe properly from the abdomen, and proper breathing is essential to meditation which is the sine qua non of Zen. Chanting a dharani is one of the best ways of emptying the mind of trivia; of settling and concentrating mind and body. Buddhist dharani are Tang or Sung Chinese transliterations of Sanskrit originals which have about the same meaning as hallelujah, hallelujah. Simple people have often considered them magic formulae. That they have certain powers is undeniable--so do aspirin pills.

The Eiheiji chanting is the simplest possible form of musical expression. It is not discursive; it does not appeal to the mind and emotions and draw them into interesting involvements. In Buddhist chanting the voice should flow naturally and easily from its source. It is said that monks who wished to learn to chant properly used to stand in front of a water fall and try to make their voices heard above the sound of the water. If the voice came from the throat or chest; if the individual didn't have his mind and body in order, exhaustion was the almost immediate result. However, if mind and body were composed, the sound could flow forth freely and even after long periods of vocal exercise no fatigue would he felt.

Christian music, like Christian thought and emotion, attempts to soar to attain the heights of the supernatural. Buddhist music finds its source in the wellsprings of being itself; bringing up from that source peace, vitality and a realization of completeness. An over stimulated ego with its involved system of enervating defense mechanisms produces anxiety, insecurity and restlessness in modern man which make it difficult for him to really listen to the sound of the wind, the sound of the ocean or music which does not express itself in a variety of alternately exciting and pacifying rhythms and tonal changes. The wind, the ocean and the chanting are not really heard unless they are seen with the ears and heard with the whole body. Westerners usually tire quickly of a monotone. Unfortunately, boredom is an escape mechanism which separates man from himself and from that which unites him with the rest of creation.

3

________________________________________

The most important function of the Sōtō ritual is that it provides a contact with the laymen. The Sōtō sect undertakes a certain amount of social work including a middle school, a high school and a junior college for girls, a hospital, an orphanage and a day nursery. These institutions are projects of the big Sōji temple in Yokohama and the Eiheiji has no part in their operation. At Eiheiji the only contact with laymen is with those who come to the temple for a night, a meal or for one of the special observances such as the memorial week in honor of the founder and the ordination ceremony for laymen, which are held once a year. The guest quarters at Eiheiji are very large; they are modern, clean and comfortable. The guests live in traditional style Japanese rooms with cushions to sit on; a hibachi (a large pottery charcoal brazier) in which is a tetsubin (iron teapot) for boiling water for tea and a tea set. In one corner is the tokonoma, a special raised platform on which is usually placed a porcelain bowl and above it hangs a kakemono, or scroll. At the Eiheiji the scrolls are usually sho (Calligraphy). In some of the rooms the fusuma (paper-doors) are also decorated with ink sketches; bamboo and birds being the preferred subjects. The guests are waited on by the monks; meals are served in each room and the futon (sleeping quilts) are brought out every night and put away each morning by a monk attendant. These attentions, as well as the various ceremonies conducted in the temple are a form of ekō. Ekō roughly translated, means turn direction but Westerners understand its meaning better when it is called sharing. The Sōtō monk is expected to share his life with all who come to the temple. Even the simplest Japanese peasant is aesthetically oriented and most Japanese have a rather developed intuition. Particularly if they know how to chant the sutras they are able to share, in a rather deep sense, the benefits of the monks' meditations. This is as much a physical as a mental thing. I once discussed the matter with an opera singer who attributed it to what she called an impulse. At the Eiheiji one might say that this impulse has been heeded through 700 years of uninterrupted dedication. The sustained striving of those who have lived in this temple (average stay for ordinary monks 1-3 years, for temple officials 3-25 years) has created an atmosphere that has a climate of its own, a climate which would fail to affect only the very self centered or insensitive.At Eiheiji a typical day begins at 3:30 o'clock in the morning. On days when there is no early morning zazen, the day begins at 4:30. From the sōdō a big building where the monks live, come the sounds of the time-telling drum and gong. About a half an hour later, two monks run through all the temple buildings ringing shinrei (small hand bells resembling western dinner bells). This is followed by the great bronze bell below the sammon. About an hour later the guests shuffle up to the hattō (main building) to attend the morning ceremony. The song of the cuckoo and the cicada soon merge into the waves of chanting and the deep voice of the

mokugyo (a large polished wooden drum which is struck with a padded stick) sending waves of deep soft sound down the mountainside.

The first sutra chanted is called the "Essence of Wisdom" sutra The sutra begins, "When the Bodhisattva, Avalokitesvara was in deep meditation on the perfect wisdom --- he perceived clearly that the five components of being are all Sunya (the formless essence) and so was saved from all kinds of suffering. Shariputra, phenomena are not different from Sunya Phenomena are Sunya and Sunya is phenomena." This sutra ends with the Sanskrit dharani Gyate gyate hara gyate harasogyate Bojisowaka" - ferry, ferry, ferry over to the other shore! (enlightenment) Ferry all beings over to the other shore. Perfect Wisdom! So may it be.

The sutras are chanted in chorus by all the monks and are followed by an ekō Here ekō means dedication. The order and choice of sutras varies somewhat each morning; but, usually chanted is the important Sandōkai. This Chinese poem was written by Hsi-ch'ien and is composed of 44 character lines. This style was very popular in the Tang and Sung Dynasties. Sandōkai may be translated as "The Union of the Spiritual and Phenomenal Worlds."

"Those who attain enlightenment meet the Shakamuni Buddha face to face, The teachings of the Masters of the South and North are but different expressions of the same thing--the awakened mind returns to the source. Clinging to reason will not produce Satori. When they enter the gates of the senses, interdependent phenomena appear unrelated. Phenomena are interdependent and, furthermore, interpenetration takes place. If there was no interpenetration, there would be no escape from differentiation. The characteristics of form are different; pleasure and suffering appear unrelated. For the unawakened, only duality is apparent. All differentiations arise from the same origin. All expressions describe the same reality.

4

________________________________________

In the phenomenal world there is enlightenment. In enlightenment can be found the phenomenal world. The two cannot be separated; they intermingle and depend on each other."--When we hear words, we should trace their source, --The visible world is only a path. As we proceed, we must realize that this is all we need to know. We are always on the path; Satori is neither near nor far. Since we cannot see the path, Satori always seems a distant goal. Those who are seeking the way, may I advise them not to waste any time."

The morning ceremony always includes the recitation of the Dai-osho, or names of the great teachers. According to the Zen tradition, an understanding of the Buddhist Dharma or teaching has passed from mind to mind since the time of the Gautama Buddha. It is said that one day, when seated amongst his disciples, the Buddha held up a flower. His disciple, Kasyapa looked at the flower and smiled. The patriarchs of Zen (some mythical and some historical) beginning with Kasyapa, are venerated as well as a number of mythical Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, symbols of Wisdom, Compassion and other Buddhist virtues. The morning ceremony usually includes the Dai-hi-shin darani or Dharani in praise of Avalokitesvara, or the impulse of Compassion. This Dharani is chanted with mokugyo at a rather fast tempo, and the surge of vitality from the figures, seated cross legged and immobile on the tatami (straw) matted floor is very compelling. The ceremony almost always concludes with the Myōhōrengekyō (Saddharma Pundarika Sutra) Juryōbonge (Chap. 16) which extols the value of sharing the Buddha's teaching. As one leaves the hattō (main hall) after this ceremony, the dawn is arising from behind the distant hills.

Most of the monk's day is spent doing samu. Even the old kanin himself does some form of manual work. The monks clean the temple, bring wood to the kitchen, make charcoal and wait on the guests. Several times a year they have sesshin or periods in which to "collect the mind." During sesshin nearly all the monks spend the whole day in the sōdō doing zazen from 2 or 3:00 in the morning till nine at night. During the sesshin periods the food is both good and plentiful. Ordinarily, the monks live on watery rice and a few equally watery vegetables.

The visitor's day may be spent taking walks in the lovely countryside around the temple, drinking tea with the senior monks when they are free or asking the Zen Master for instruction in zazen. If sleepy from early rising one simply curls up like a cat on the tatami floor of one's room for a nap. The tatami are clean and beautiful and smell of sun and fields. The food served to the visitor is called shojin--ryori and is completely vegetarian. However, Eiheiji's cook is a master of his art and, even when the number of visitors is large, the food is varied and good. It is served on lacquer trays in many little lacquer dishes and includes such specialties as lotus buds in syrup and tiny oak leaves fried in deep fat. Life is very comfortable for a western visitor if he can sit comfortably on his heels for long periods, doesn't mind shaving in cold water and likes rice, pickles and cold spinach with soy sauce for breakfast. Each meal is preceded by a grace which the monk who serves it chants for those who don't know it. The day ends with a Japanese style bath which is one of the real delights of Japanese life. Outside the bathroom is an anteroom where one leaves one's clothes and makes a gasshō and lights a stick of incense and places it in a tiny brass dish in front of a little plaque on which are characters which mean, "sweet smelling water." The bathroom is a large tiled room in which is a big square tub with a seat at each end. First one soaps, and then rinses with water which must be taken from the tub in a small wooden box. After this procedure, one clambers into the tub and soaks in the steaming water for a while. After the bath, one may take a cold shower and then return to one's room, feeling quite ready for sleep.

One night I passed a room where the shōji was just slightly ajar. Inside, a tiny little old woman with a shaven head and wearing very worn black cotton nun's robes was sitting on her heels in front of her hibachi. She was sitting completely motionless. It was impossible to tell whether she was asleep or awake. Her work swollen hands were joined in a gasshō and on her thin wrinkled face was what one art critic has called the archaic smile, the enigmatic smile of the sphinx, the dancing Shiva; the stone Buddhas of Tang, the Mona Lisa, the smile of Maha Kashapa; in that serene smile of the little old nun -- wisdom of the Buddhas and the Patriarchs, the wisdom which cannot be taught; but can be found and embodied.

5

________________________________________

The material on these two discs has been taken from tape recordings of about fourteen hours length. Needless to say, almost none of the ceremonies could be included in entirety, nor could any bell or gong sequence be retained in its original length. However, all the sounds and ceremonies heard on a typical day in the temple are represented. As for the order of the material, this has been kept as accurate as possible. Most of the recordings were made over a period of about a week in September of 1957; however, several ceremonies were recorded two years later. Some of the difficulties involved in accurately documenting a typical day were that first of all, in such a large temple several ceremonies may be carried on simultaneously and, secondly, special ceremonies, which are a regular part of the temple life, are performed at different times of the month and a typical day would probably not include more than two or three of such ceremonies.The listener may wonder why we have included repetitions of certain sutras and particularly dharanis. The reason for this is that though many of the sutras and scriptures chanted are carefully studied by both priests and scholarly lay adherents, their use in ritual is not to teach conceptually; but to create a certain kind of atmosphere. This atmosphere is only incidentally aesthetic in quality. It is the state of mind which is important. Ceremonies are not meant to hypnotize the participants into apathy. The mind should become quiet, clear and receptive, so that it may know what is beyond concepts and beneath activity. In this experience mind and body must both participate. Nor is ritual meant to provide a special time and place for the experience in question. A ceremony should be an extension of zazen; as is washing the lavatory, weeding the garden and attending to the wants of visitors. Though a monk removes his muddy samu (work) suit and puts on a silk robe before participating in a ceremony, his frame of mind is meant to remain the same as in his zazen.

Record I side I begins with the time-telling drum and gong (kōten). The drum announces the hour and the gong the minutes. This is followed by a small hand bell, similar to a Western dinner bell (shinrei). Next we hear the meditation bell (kyōshō). This bell

(ōbonshō) hangs in its own special housing just below the main gate (sammon). It is rung during the 45 minute meditation period; forty five minutes is the length of time it takes to burn one incense stick (senkō). In the background can be heard cicadas; the voice of a cuckoo and the rush of water flowing down the mountain side.

The novices live in a large wooden building called the sōdō. Inside the sōdō are raised platforms (tan) which are covered with rice-straw (tatami) mats 6 feet in length by three feet in width. Each monk is provided with the space of one tatami mat where he eats, sleeps and meditates. Outside the main hall of the sōdō is a rather wide corridor, on one side of which is one long tan. Only monks living in the temple may enter the main hall, the adjoining corridor accommodates postulant novices, visiting monks and lay people (for meditation only). Also in this corridor there is a very large drum on a stand (sōdōku) a small bell (sōdōshō) and a very large wooden gong in the shape of a fish

(hō)* as well as a small wooden board which, like the aforementioned bell and gong, is hit with a wooden mallet.

*Probably symbolizes constant wakefulness and perseverance.

After the meditation bell, a metal gong (dai kaijo) and the small board in the sōdō are hit alternately. At the end of this sequence the sōdō bell (naitanshō) is rung once. This is called chūkaishō or "getting loose the crossed legs": In the background can be heard the ubiquitous cicada. Then follows the verse for putting on the kesa (Takkesa-ge). This verse (Jap. ge 偈; Skt. gatha) indicates the donning of the outside garment (kesa) which resembles part of the robe traditionally worn by South East Asian monks. In South East Asia, Buddhist monks do not do any manual labor and their rather clumsy toga-like garment is suitable for such a life in a hot climate. However, in China and Japan where it is cold and the monks of some sects must do manual work, the original Buddhist robe would be very impractical. In Japan, the full kesa is worn over a koromo (a kind of kimono) for ceremonies and on all formal occasions. On other occasions it is usually replaced by a small cloth square which is suspended from a band which goes around the neck. This square is called a rakusu.

After the chanting for the kesa, we proceed to the hattō (teaching hall) for the morning ceremony. This ceremony (chōka) is announced by a small bronze bell (denshō) which hangs outside one of the entrances. The hattō is a very large tatami-floored building, which is used for all important services.

The morning ceremony begins with the chanting of the Hannya shingyō. The chanting is accompanied by a large bronze instrument called a keisu. Following the Hannya shingyō, we hear the Sandōkai; ekō; (which includes a recitation of the Dai Oshō* and the Juryōbonge, the translation of which is too long to be included in this booklet. Occasionally during the ceremony, the dawn drum (gyōku) can be heard in the background. Also, in the beginning of the Hannya shingyō one can hear the cuckoo and cicada.

*At the beginning of the chanting of the Dai Oshō, a small keisu is struck several times with an unpadded stick, as in the Fusatsu ceremony.

The second side of the first record begins with a bell (denshō) which is followed by two wooden gongs (hō and kairōban); a gong (arhatsuban); wooden clappers (kaishaku); and a drum (dai rai), These sounds indicate the preparation for breakfast. The food is taken from the kitchen to the sōdō (except when the monks eat in the hall just outside the kitchen). Punctuated by the clappers we hear the verses for eating (Jikiji-ho). The dai rai is heard again after the first part of the Jikiji-ho. Ordinarily this drum just precedes the breakfast. During this time an offering is made to the Monju Bodhisattva (symbol of wisdom) who is enshrined in the center of the sōdō Before the sound of the drum, you will hear a clock striking in the background. After the "thunder drum" (dai rai) the wooden clappers are heard and the chanting for eating continues. During this chanting the monks untie the napkins which contain their eating sets. These consist of a few bowls and chopsticks. After the chanting, the food is dished out of big wooden pails by waiter monks. In the background can be heard the sound of doors being opened and closed, as well as footsteps.

6

________________________________________

The formal eating ceremony is very similar to the tea ceremony. Both are conducted in silence and are meant to absorb the participant's attention completely. This is a part of the traditional Buddhist discipline of "mindfulness." On the record there is a short interval of silence between the before and after breakfast chanting. Just before the final verse, a monk announces the date (Sept.15, '57) and duties are assigned to monks. This is followed by the wooden clappers and a bell,The next ceremony is a special one held in the jōyōden or shrine of the founder (Dōgen Zenji) on the fifteenth of each month. First the bell (denshō) announcing the ceremony is heard. While this bell is being rung the monks file into the jōyōden. The latter is a rather small building with a stone floor. Lay people do not usually enter this building during ceremonies. After the bell we hear the Dai-hi-shin darani (for a translation, see Suzuki "Manual of Zen Buddhism" p. 22) which is accompanied by the mokugyo. The Dharani is followed by an ekō and the refrain ''Jiho sanshi ishi fu; Shison busa mokosa, moko hoja horomi" (Homage to all Enlightened ones, past, present and future, everywhere; to the many Bodhisattva Mahasattvas; to the maka-prajna paramita).

The next ceremony is perhaps the most appreciated by the monks. It takes place twice a month (15th and 30th or 31st day) and is called Ryaku fusatsu. It is held in the butsuden (shrine of Shakyamuni). We hear short portions of this ceremony beginning with ''Namu Shakamuni Butsu" (Homage to the Shakyamuni Buddha). This is followed by the vow of the Bodhisattva ("Shiguseigan"). After the Fusatsu, we hear the last part of the Hannya shingyō accompanied by the mokugyo and keisu.

The ceremony for the 500 Enlightened Ones (Skt. Arhat) is also held on the 15th of each month. It takes place in the room above the main gate (sammon). The room in which this ceremony is held is rather small and the acoustics are not very good.

Side two of this record ends with the midday service which is held in the Butsuden. It begins with the striking of the keisu and continues with the Bucchō sonshō darani (Dharani of the Victorious Buddha Crown)* which is accompanied by the mokugyo. The listener may sometimes notice lulls in the chanting. Also, when there is no keisu or mokugyo to regulate the tempo, the waves of sound roll and break over each other at rather irregular intervals. This is considered quite natural.

*Suzuki , Manual of Zen Buddhism, p. 23.

Record two, side I begins with the deep tones of the keisu in the hattō. This announces the beginning of "the Fire Protection Ceremony", from which we hear part of the Juryōbonge.

Fire protection ceremonies are held in all Japanese temples and shrines (Buddhist and Shinto). Fire is an omnipresent hazard as the buildings contain many inflammable materials. Temples and houses, originally built hundreds of years ago, may have burned to the ground many times during the course of their existence. As many times as they are destroyed, they are rebuilt, usually in the same style and in the same place.

Buddhist philosophy does not condone petitionary prayer or any attempt to cajole a supernatural force into watching out for human interests; however, popular Buddhism has accepted and absorbed those indigenous practices which are based on deep seated human hopes and fears. These practices have been gently manipulated and molded to fit harmoniously into the structure of the Buddhist framework. And, it is important to remember that Buddhism teaches that intellection alone is not capable of probing the secrets of the universe. The great mysteries of change; of death and regeneration must be approached differently to be truly apprehended.

Following this Dharani there is a short silence and then footsteps are heard. The listener has left the hattō and entered the kitchen shrine which is somewhat removed from the hattō In this shrine one young monk chants the Dai-hi-shin darani with ekō and refrain.

For the next sequence let us proceed to a small room on the other side of the temple where newly arrived novices are interviewed by the temple authorities. In this room we see a novice sitting cross-legged facing the wall. A senior monk enters, carrying in one hand a flat stick (kyōsaku*) used for discipline and for preventing sleep during meditation periods; in the other hand he carries the temple register which the postulant monk will be asked to sign if and when he is accepted. The following conversation ensues:**

*The disciple is whacked several times on one or both shoulders. Before and after the beating, the monk receiving the kyōsaku is expected to gasshō politely.

**In the background can be heard the footsteps of monks walking by the open door and a clock ticking.

7

________________________________________

Monk: "What have you come here for?"

Novice: "I have come to show my gratitude (On) for the master's teaching (to learn Dōgen's teaching)."

Monk: "And how do you intend to go about showing this gratitude?"

Novice: "By not clinging to myself, I think."

Monk: "That's all right. And do you really intend to persevere to that extent?" (Without waiting for an answer he continues) "What was written on the sammon?" (silence) "What was written there?"

Novice: "I don't know."

Monk: "Do you always enter houses even when you don't know what lies within?" (Pause) "It is all right that you don't know." (Another pause)

Monk: "Where did you stay last night?"

Novice: "In the station in Fukui."

Monk: "There is an inn just below the sammon where you could have stayed.

Novice: "I intended to come last night but neither the train nor the electric car was running."

Monk: "Um! The founder can be served in your home (you can study the teaching, of Dōgen in your home)."

Novice: "Yes."

Monk: "To take the trouble to come to this temple (honzan) was unnecessary, wasn't it? It was unnecessary to come here..."

Trans. S. IharaHere we leave the interview.

Next we enter a large room with a low ceiling, where about thirty monks are kneeling in front of' long benches on which are placed their sutra books. The chanting leader (ino) who is seated in front of them at a small desk, is giving instruction in the technique of chanting the shōmyō. The shōmyō is a verse (Skt. gatha) of praise to the Buddha and, as in Western music, there is a kind of melody. In Zen ceremonies the shōmyō is not used very often. This style of chanting is more popular in the Shingon and Tendai sects. The aesthetic principle of yūgen is observed in the shōmyō. Yūgen is very difficult to translate. It suggests the depths of the infinite or the sound of eternal stillness. Yūgen points beyond the finite and the transitory to the source of form.In this lesson the ino asks his pupils to chant parts of the shōmyō on successively higher pitches.

We leave the music lesson and proceed to* the visitor's quarters where we hear a portion of the Jikiji-ho being chanted in one of the guest rooms. These guest rooms are bedrooms at night, at which time the sleeping quilts (futon) are spread on the floor. In the daytime the quilts are removed and the rooms become living and dining rooms. Meals are served here by the monks who bring the food on individual lacquer trays. Before eating one or, in some cases, two monks and the guests chant the Jikiji-ho.

* Note footsteps before chanting

We leave the guest room (note footsteps on record) and go down the long corridor to the Butsuden. The first sounds we hear are the denshō alternating with the inkin. The inkin is a very small version of the keisu and is carried by one of the monks in the procession which is filing into the hall. After these bells, we hear the Dai-hi-shin darani preceded by the keisu and accompanied by the heart beat-like sound of the mokugyo. The Dharani is followed by an ekō and refrain.**

** Memorial service for Dōgen's Chinese master, Ju-tsing, held on the 16th of each month.

0n side two of the second record are the last ceremonies of the day, including an evening ceremony and memorial service for the dead (Segaki).*** In the Segaki special instruments are used. There are small bells (inkin), a drum (shōku) suspended from a stand and a large pair of cymbals (nyōhachi). The first sutra heard is kanromon (Gate of Immortality) and the second is chapter IV of the Shushogi (Taking vows and the Enlightenment of Beings). This important text (for Sōtō-shū) was written by Dōgen. During the chanting a monk can be heard (in the background) telling the lay people when to stand and when to proceed to the altar to make an incense offering.

*** An important omission from this selection of daily events is the chanting of the Fukanzazengi which is heard at the end of the evening zazen (yaza). Yaza is held from seven to nine, or from eight till nine P. M.

8

________________________________________

Below are a few excerpts from the chapter which is chanted:. . . One's appearance may be insignificant, but if the bodhicitta (desire to seek the Truth) is aroused one is a leader of all sentient beings. One may even be a seven year old girl ... in the Buddhas religion no distinction is made between the sexes ... A spiritual gift is a material gift; a material gift is also spiritual. And nothing should be expected in return for what is given.... Beneficial practice means any action which benefits any sentient being. When one sees a tortoise in distress or a sick sparrow, one is prompted to rescue them without expecting anything in return from them.... Self and others are inextricably interrelated and interdependent.... A sea refuses no stream to flow into it .... water when accumulated extends far and deep... In the vows and practices of one who has aroused his mind to Bodhi, such lines of thought should be followed in quiet meditation.

While this chanting is going on we leave the hattō and walk down one of the roofed corridors and then, turning right, ascend the steps which lead to the Joyosho. In front of the jōyōden is the evening bell (konshō) which is rung for a half an hour. In this recording the sound of rain on the tile roof of the corridor can be heard. When we return to the hattō the monks are chanting Myōhōrengekyō Fumonbonge (*Chap. 25 of the Myōhōrengekyō). The evening ceremonies end with the drum, cymbals and inkin which accompany the refrain (Jiho sanshi...). Next we hear the hattō bell and finally the deep sound of the keisu. Thus ends another day in the life of the 700 year old temple.

*Not in Skt. version.

Glossary

Revised Edition by G. Terebess

arhatsuban (=ahatsuban, ahatsuhan) 下鉢版 (gong in the dai kuin)

Bucchō sonshō darani 佛頂尊勝陀羅尼 ("Dhāraṇī of the Victorious Buddha Crown")

butsuden 佛殿 (Buddha Hall)

chōka 朝課 (morning service)

chokushimon 敕使門 (Imperial Messenger's Gate), aka 唐門、karamon (Chinese Gate,

generic term for

a gate with an arched roof)

chūjakumon 中雀門 (Central Gate)

chūkaishō

抽解鐘 (uncrossing legs after zazen)

Dai-hi-shin darani 大悲心陀羅尼 ("Dhāraṇī of Great Compassion")

dai kaijō 大開静 (bell which announces the end of zazen)

dai kuin 大庫院 (large guest quarters; kitchen hall)

dai-oshō 大和尚 (great teacher; patriarchs of the Sōtō sect)

dai rai 大雷 (thunder drum, sōdō drum)

darani 陀羅尼 (dhāraṇī is a Sanskrit term for a type of ritual speech similar to a mantra)

denshō 殿鐘 (a small bronze bell hung outside halls and used to announce ceremonies; there is also one inside the sōdō)

Dōgen Zenji 道元禅師 = [永平] 道元希玄 [Eihei] Dōgen Kigen (1200–1253)

Eiheiji 永平寺 (The Temple of Infinite Peacefulness)

. . . . .

The Eihei (Ch.: Yongping) era in the Later Han dynasty lasted from 58 to 76 c.e. It is said that in the tenth year of this era (67 c.e.), the first Buddhist sutras were introduced to China. Later, in 1246, Dōgen would . . . . . . . . therefore rename the temple he founded in Echizen after Eihei, and it is still called Eiheiji.

ekō 回向 (short dedication chanted after sutras)

Fumonbonge 普門品偈 (Verse of the “Universal Gateway,” chapter 25 of the Myōhōrengekyō

妙法蓮華経)

fusuma 襖 (sliding door or panel made of heavy cardboard)

futon 布団 (sleeping quilts)

gasshō 合掌 (palms joined in attitude of prayer; left hand sympolizes the phenomenal world and the right hand the spiritual world)

ge 偈; Skt. gatha

(poetic verse of a scripture)

geta 下駄 (wooden clogs)

gyōku 暁鼓 (dawn drum (in the sōdō), struck during the morning service

Hannya shingyō

=Maka hannya haramitta shingyō 摩訶般若波羅蜜多心経

hattō 法堂 (main building for ceremonies)

hibachi 火鉢 (small china or metal brazier used for heating rooms)

hō 梆 (wooden gong in the shape of a fish which hangs in the sōdō)

honzan 本山 (head temple)

Hsi-ch'ien = Shitou Xiqian 石頭希遷 (700-790)

inkin 引磬 (hand gong)

ino 維那 (leader of chanting)

jōyōden 承陽殿 (shrine of Dōgen)

Juryōbonge (Verse of the "Life Span," chapter 16 of the Myōhōrengekyō

妙法蓮華経)

Ju-tsing (=Ju-ching) = Tiantong Rujing 天童如净 (1163–1228)

kairōban 廻廊版 (wooden gong)

kaishaku 戒尺 (wooden clappers)

kakemono 掛物 (hanging scroll)

kanin

監院

(monk in charge of all temple activities)

kanromon 甘露門 (Ambrosia Gate)

keisu 磬子 (a large bronze instrument shaped like a bowl)

kesa 袈裟 (monk's outer garment worn over koromo)

kinhin 經行 (walking around in the sōdō between zazen periods)

konshō 昏鐘

(the evening ringing of the large temple bell)

koromo 衣 (a special kimono worn by priests)

kōten 更点 (time-telling drum and gong)

kufū

工夫 or

功夫

(zazen in which one struggles by oneself;

cf. Dōgen: kufū bendō 功夫辦道 (concentrated endeavor of the way); Hakuin: shōnen kufū 正念工夫 (right mindful skillful effort).

kyōsaku 教策 (flat stick)

kyōshō 夾鐘 (meditation bell)

mokugyo 木魚 (big hollow wooden drum)

Monju 文殊 (Mañjuśrī)

naitanshō 内單鐘 (bell rung after zazen)

nyōhachi 鐃鉢 (cymballs)

ōbonshō 大梵鐘 ("Big Brahman's Bell"; the biggest bronze bell in the temple)

P'ang-yun = Pang Yun 龐蘊居士 (740-808)

rakusu 絡子 (cloth square suspended from the neck by a band; substitute for the kesa)

Ryaku fusatsu

略布薩 (Precepts Renewal Ceremony)

sanmon 三門 or 山門 (the gate in front of the butsuden. The name is short for Sangedatsumon (三解脱門), lit. Gate of the three liberations)

. . . . . Its three openings (kūmon (空門), musōmon (無相門) and muganmon (無願門) symbolize the three gates to enlightenment.

. . . . . Entering, one can free himself from three passions (貪 ton, or greed, 瞋 shin, or hatred, and 癡 chi, or "foolishness")

samu 作務 (manual labor)

sanshi-mompō 参師聞法 (asking the master about the Buddha's teaching)

satori 悟り (enlightenment)

segaki 施餓鬼 (memorial service for the dead; "feeding the hungry ghosts")

senkō 線香 (incense stick)

sesshin 攝心 (a week-long period of intensive zazen)

Shiguseigan 四弘誓願 (“The Four Encompassing Vows”)

shinrei 振鈴 (hand bell rung in the morning to awaken everyone in the temple)

sho 書 (calligraphy)

shōji 障子 (sliding paper door)

shōku 小鼓 (small drum on stand)

shōmyō 声明 (a verse of praise to the Buddha)

sōdō 僧堂 (hall where monks in training live; in the Rinzai sect it is called zendō 禅堂)

sōdōku 僧堂鼓 (big drum in the sōdō)

sōdōshō 僧堂鐘 (small bronze bell which hangs in the sōdō)

Sōtō-shū 曹洞宗 (sub-sect of zen founded by Dōgen)

tan 單 (raised platforms in the sōdō)

tatami 畳 (straw matting)

tetsubin 鉄瓶 (iron kettle for boiling tea)

tokonoma 床の間 (alvove in which objects d'art are placed)

tōsu

東司 (monk's lavoratory)

yaza 夜坐 (evening zazen)

yūgen 幽玄

(subtly profound grace, not obvious)

zazen 坐禅 (to sit in meditation)

Cf.

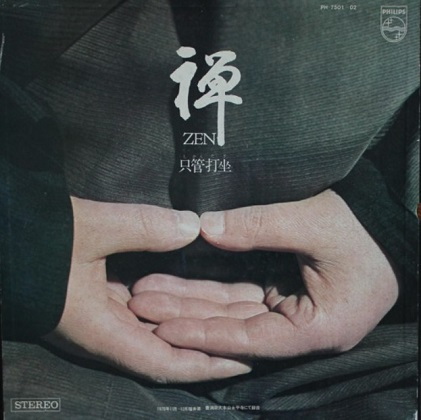

禅 (只管打坐) "Zen: Shikantaza - Sotoshu Daihonzan Eiheiji" | Soto zen Eiheiji Temple atmospheres

Philips PH-7501|02 - Nov-Dec. 1970 - 33 rpm, Vinyl LP, 1:18:30, Nippon Phonogram Co. Ltd.

Fukui Prefecture of Sotoshu Daihonzan Eiheiji [Soto zen monks of Eiheiji Temple]

https://soundcloud.com/ben-gerstein/zen-shikantaza

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qTcqIleWdUo

Track listing

A1

永平寺の朝 Eihei-ji no chō (Eihei-ji Morning Service)

A2a

法堂にて, 般若心経~回向 Hattō-nite (Dharma Hall ceremonies), Hannya shingyō ~ Ekō (dedicate merit)

A2b

参同契~回向 Sandōkai (Harmony of Difference and Equality) ~ Ekō (dedicate merit)

B1a

法堂にて, 回向~宝鏡三昧 Hattō-nite (Dharma Hall ceremonies), Ekō (dedicate merit) ~ Hōkyō zanmai (Precious Mirror Samādhi)

B1b

回向~大悲心陀羅尼 Ekō (dedicate merit) ~ Dai-hi-shin darani (Dhāraṇī of Great Compassion)

B2

禅問答 Zen mondō (Zen questions and answers)

C1a

展鉢之偈~十仏名 Tenpatsu no ge (Opening Bowls Verse) ~ Jūbutsumyō (Ten Buddha Names)

C1b

粥時咒願~食事五観之偈 Shukuji jugan (gruel time incantation) ~ Go kan no ge (Five Contemplations Verse)

C1c

擎鉢之偈 Kei hatsu no ge (Bowl Raising Verse)

C2

折水之偈~後唄 Sessui no ge (Rinse Water Verse) ~ Gobai

C3

托鉢 Takuhatsu (alms gathering)

D

普勧坐禅儀 Fukan zazengi (Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen)

1. 三門、山門、Sanmon (Main Gate)

2. 仏殿、Butsuden (Buddha Hall)

3. 法堂、Hattō

(Dharma Hall)

4. 僧堂、Sōdō (Monk's Hall)

5. 大庫院、Daikuin (Kitchen)

6. 浴室、Yokushitsu

(Bath)

7. 東司、Tōsu (Toilet)

8. 承陽殿、Jōyōden (Founder's Hall)

9. 鐘楼堂、Shōrōdō (Belfry)

10. 勅使門、Chokushimon (Imperial Messenger's Gate), aka 唐門、Karamon (Chinese Gate)

11. 祠堂殿、Shidōden

(Memorial Hall)

12. 中雀門、Chūjakumon (Central Gate)

13. 傘松閣、Sanshōkaku (Lay Reception Hall)

14. 吉祥閣、Kichijōkaku (Main Reception Hall)

Chief Abbots (Kanshu) of Eihei-Ji 永平寺贯首

https://eiheizen.jimdo.com/

(1) Dōgen 道元 (1200–1253)

(2) Koun Ejō 孤雲懷奘 (1198–1280)

(3) Tettsū Gikai 徹通義介 (1219–1309)

(4) Gi'en 義演 (d. 1314)

(5) Gi'un 義雲 (1253–1333)

(6) Donki 昙希

(7) Iichi 以一

(8) Kishun 喜纯

(9) Sōgo 宋吾

(10) Eichi 永智

(11) Soki 祖机

(12) Ryōkan 了鉴

(13) Kenkō 建纲

(14) Kenzei 建撕

(15) Kōshū 光周

(16) Sōen 宗缘

(17) Ikan 以贯

(18) Sotō 祚栋

(19) Sokyū 祚久 (d. 1610)

(20) Daien Monkaku 大圆门鹤 (d. 1615)

(21) Kaigen Sōeki 海岩宗奕 (d. 1621)

(22) Jōchi Soten 常智祚天 (d. 1631)

(23) Butsuzan Shūsatsu 佛山秀察 (d. 1641)

(24) Kohō Ryūsatsu 孤峰龙札 (d. 1646)

(25) Hokugan Ryōton 北岸良顿 (d. 1648)

(26) Tenkai Ryōgi 天海良义 (d. 1650)

(27) Ryōgan Eishun 岭岩英俊 (d. 1674)

(28) Hokushū Monsho 北洲门渚 (d. 1660)

(29) Tesshin Gyoshū 铁心御州 (d. 1664)

(30) Kōshō Chidō 光绍智堂 (d. 1670)

(31) Gesshū Sonkai 月洲尊海 (d. 1682)

(32) Dairyō Gumon 大了愚门 (d. 1687)

(33) San'in Tetsuō 山阴彻翁 (d. 1700)

(34) Fukushū Kōiku 馥州高郁 (d. 1688)

(35) Handō Kōzen 版桡晃全 (d. 1693)

(36) Yūhō Honshuku 融蜂本祝 (d. 1700)

(37) Sekigyū Tenryō 石牛天梁 (d. 1714)

(38) Ryokugan Gonryū 绿岩岩柳 (d. 1716)

(39) Shōten Sokuchi 承天则地 (d. 1684)

(40) Daiko Katsugen 大虚喝玄 (d. 1736)

(41) Gikō Yūzen 义晃雄禅 (d. 1740)

(42) Kōjaku Engetsu 江寂圆月 (d. 1750)

(43) Ougen Mitsugan 央元密岩 (d. 1761)

(44) Daikō Etsushū 大晃越宗 (d. 1758)

(45) Hōzan Tankai 宝山湛海 (d. 1771)

(46) Misan Ryōjun 弥山良顺 (d. 1771)

(47) Tenkai Tōgen 天海董元 (d. 1786)

(48) Seizan Taimyō 成山台明 (d. 1793)

(49) Daikō Kokugen 大耕国元 (d. 1794)

(50) Gento Sokuchū 玄透即中 (d. 1807)

(51) Reigaku Egen 灵岳惠源 (d. 1806)

(52) Dokuyū Senpō 独雄宣峰 (d. 1835)

(53) Busshin Ikai 佛星为戒 (d. 1818)

(54) Bakuyō Mankai 博容卍海 (d. 1821)

(55) Ensan Dai'in 缘山大因 (d. 1826)

(56) Mu'an Ungo 无庵云居 (d. 1827)

(57) Saian Urin 载庵禹隣 (d. 1845)

(58) Dōkai Daishin 道海大信 (d. 1844)

(59) Kanzen Chōsō 观禅眺宗 (d. 1848)

(60) Gaun Dōryū 臥雲童龍 (1790-1870) Birthname: Murakami Dōryū 上村童龍

(61) Kuga Kankei 久我環溪 (1817-1884) Dharma name: Kankei Mitsūn 環溪密雲

(62) Aokage Sekkō 青蔭雪鴻 (1831-1885) Dharma name: Tekkan Sekkō 鐵肝雪鴻

(63) Takiya Takushū 滝谷琢宗 (1836-1897) Dharma name: Rozan Takushū 魯山琢宗

(64) Morita Goyū 森田悟由 (1834-1915) Dharma name: Daikyū Goyū 大休悟由

(65) Fukuyama Mokudō 福山黙童 (1841-1916) Dharma name: Juken Mokudō 壽硯黙童

(66) Hioki Mokusen 日置黙仙 (1847-1920) Dharma name: Ishitsu Mokusen 維室黙仙

(67) Kitano Gempō 北野元峰 (1842-1933) Dharma name: Genpō Daien 元峰大夤

(68) Hata Eshō 秦 慧昭 (1862-1944) Dharma name: Mokudō Eshō 黙道慧昭

(69) Suzuki Tenzan 鈴木天山 (1863-1941) Dharma name: Hakuryū Tenzan 白龍天山

(70) Ōmori Zenkai 大森禪戒 (1871-1947) Dharma name: Katsuryū Zenkai 活龍禪戒

(71) Takashina Rōsen 高階瓏仙 (1876-1968) Dharma name: Gyokudō Rōsen 玉堂瓏仙

(72) Sagawa Geni 佐川玄彝 (1866-1944) Dharma name: Kunzan Geni 訓山玄彝

(73) Kumazawa Taizen 熊澤泰禪 (1873-1968) Dharma name: Sogaku Taizen 祖學泰禅

(74) Satō Taishun 佐藤泰舜 (1890-1975) Dharma name: Hakuei Taishun 博裔泰舜

(75) Yamada Reirin 山田霊林 (1889-1979) Dharma name: Juhō Reirin 鷲峰霊林

(76) Hata Egyoku 秦 慧玉 (1896-1985) Dharma name: Meihō Egyoku 明峰慧玉

(77) Niwa Rempō 丹羽廉芳 (1905-1993) Dharma name: Zuigaku Renpō 瑞岳廉芳

(78) Miyazaki Ekiho 宮崎奕保 (1901-2008) Dharma name: Sengai Ekiho 栴崖奕保

(79) Fukuyama Taihō 福山諦法 (1932-2021) Dharma name: Zetsugaku Taihō 絶学諦法

(80) Minamisawa Dōnin 南澤道人 (1927-) Dharma name: Mokushitsu Genshō 黙室玄照

PDF: Is Dōgen's Eiheiji Temple “Mt. T'ien-t'ung East”?: Geo-Ritual Perspectives on the Transition from Chinese Ch'an to Japanese Zen

by Steven Heine

In: Zen Ritual: Studies of Zen Buddhist Theory in Practice, 2008, Chapter 4, pp. 139. ff.

禅の修行 Zen no shugyō - 曹洞宗永平寺 Sōtō-shū Eiheiji

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=unteNZibuIQ