ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

圭峰宗密 Guifeng Zongmi (780–841)

(Rōmaji:) Keihō Shūmitsu

Tartalom |

Contents |

| Miklós Pál A Csan buddhizmus és a történetírás |

Inquiry into the Origin of Humanity: PDF: Tsung-mi and the Single Word "Awareness" (chih) PDF: Tsung-mi's Perfect Enlightenment Retreat: Ch'an Ritual During the T'ang Dynasty PDF: Zongmi’s Yuanren lun (Inquiry into the Origin of the Human Condition): PDF: The Integration of Ch'an/Sŏn) and the Teachings (Chiao/Kyo) in Tsung-mi and Chinul PDF: Tsung-mi and the Sinification of Buddhism PDF: The Buddhism of the Cultured Elite PDF: What Happened to the "Perfect Teaching"? Another look at Hua-yen Buddhist hermeneutics. PDF: Sudden Enlightenment Followed by Gradual Cultivation: Tsung-mi's Analysis of mind PDF: Tsung-Mi, His Analysis of Ch'an Buddhism PDF: The mind as the buddha-nature: The concept of the Absolute in Ch'an Buddhism PDF: Treatise on the Origin of Humanity (Taishō Volume 45, Number 1886) PDF: Hongzhou Buddhism in Xixia and the Heritage of Zongmi PDF: Tangut Chan Buddhism and Guifeng Zong-mi PDF: The Man in the Middle: An Introduction to the Life and Work of Gui-feng Zong-mi Hu Shih.

Ch'an (Zen) Buddhism in China: Its history and method The Northern Ch'an School And Sudden Versus Gradual Enlightenment Debates In China And Tibet |

Guifeng Zongmi was a Tang dynasty Buddhist scholar-monk, installed as fifth patriarch of the 華嚴 Huayan (Japanese: Kegon; Sanskrit: Avatamsaka) school as well as a patriarch of the Heze lineage of Southern Chan.

原人論 Yuan-ren-lun [Gen-nin-ron]

(Taishō No. 1886)

In this work, also known as the Ke-gon-gen-nin-ron (Ch.: Hua-yen-yuan-ren-lun ), Zong-mi, who advocated the amalgamation of Chan and Hua-yen, deals with the subject of the basis of human existence. He starts by criticizing Confucianism and Taoism and rejecting Hīnayāna and ‘Provisional' Mahāyāna, after which he goes on to explain the true Mahāyāna, and then concludes by stating that all the viewpoints and philosophies which he has so far criticized are in fact factors which help to effect the manifestation of the true basis of human existence. One can thus say that in this work Zong-mi is attempting to bring together all teachings in a united whole.

Zongmi on Chan

by Jeffrey Lyle Broughton

New York : Columbia University (Translations from the Asian classics), 2009, xv, 348 p.

Review http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=25154Japanese Zen often implies that textual learning (gakumon) in Buddhism and personal experience (taiken) in Zen are separate, but the career and writings of the Chinese Tang dynasty Chan master Guifeng Zongmi (780-841) undermine this division. For the first time in English, Jeffrey Broughton presents an annotated translation of Zongmi's magnum opus, the Chan Prolegomenon, along with translations of his Chan Letter and Chan Notes.

The Chan Prolegomenon persuasively argues that Chan "axiom realizations" are identical to the teachings embedded in canonical word and that one who transmits Chan must use the sutras and treatises as a standard. Japanese Rinzai Zen has, since the Edo period, marginalized the sutra-based Chan of the Chan Prolegomenon and its successor text, the Mind Mirror (Zongjinglu) of Yongming Yanshou (904-976). This book contains the first in-depth treatment in English of the neglected Mind Mirror, positioning it as a restatement of Zongmi's work for a Song dynasty audience.

The ideas and models of the Chan Prolegomenon, often disseminated in East Asia through the conduit of the Mind Mirror, were highly influential in the Chan traditions of Song and Ming China, Korea from the late Koryo onward, and Kamakura-Muromachi Japan. In addition, Tangut-language translations of Zongmi's Chan Prolegomenon and Chan Letter constitute the very basis of the Chan tradition of the state of Xixia. As Broughton shows, the sutra-based Chan of Zongmi and Yanshou was much more normative in the East Asian world than previously believed, and readers who seek a deeper, more complete understanding of the Chan tradition will experience a surprising reorientation in this book.Transliteration Systems

Abbreviations

Introduction

1. Translation of the Chan Letter

2. Translation of the Chan Prolegomenon

3. Translation of the Chan Notes

Appendix 1. Editions Used in the Translations

Appendix 2. Pei Xiu's Preface to the Chan Prolegomenon in the Wanli 4 (1576) Korean Edition

Appendix 3. Song Dynasty Colophon to the Chan Prolegomenon as Reproduced in the Wanli 4 (1576) Korean Edition

Notes

Glossary of Chinese Characters

Bibliography

Index

Broughton, J.,

Tsung-mi's Zen Prolegomenon: Introduction to an Exemplary Zen Canon.

In: The Zen Canon: Understanding the Classic Texts. (Eds. S. Heine & D. S. Wright), 2004.https://sites.google.com/site/mahabodhienglish/discover-now-the-true-dharma-path/the-chan-home-study-advanced-series/secret-chan/disturbing-chan-and-zen-revelations/chan-teachings/the-secret-heart-of-the-chan-forest/seis-maestros-del-edad-de-oro/tsung-mi

http://www.wisdom-books.com/ProductDetail.asp?PID=19212Zongmi on the Two Hindrances Translated by Charles Muller

http://www.acmuller.net/twohindrances/zongmi.htmlMaster Gui Feng Zong Mi and Monk Question and Answer Session

http://www.vzmla.org/master-gui-feng-zong-mi-and-monk-question-and-answer-session/

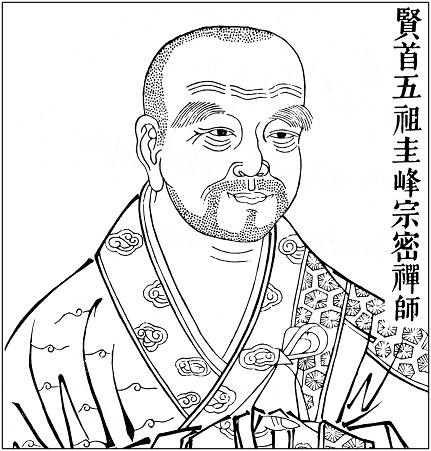

Portrait of Guifeng Zongmi (Keihō Shūmitsu; 780–841).

Hanging scroll. Ink with color on silk. 95 × 53 cm.

Late fourteenth to early fifteenth centuries.

One of a set of four portraits of Kegon school patriarchs in the possession of Kumida-dera in Osaka prefecture.

33/6. Huineng (638–713)

34/7. Heze Shenhui (670–762)

35/8. Weizhou Ji

35/8. Jingzhou Huijue

35/8. Taiyuan Guangyao

35/8. Fuzhou Lang

35/8. Xiangzhou Jiyun

35/8. Dayuan

35/8. Moheyan

35/8. Jingzhu Puping

35/8. Heyang Huaikong

35/8. Jingzhou Yan

35/8. Fucha Wuming

35/8. Hengguan

35/8. Luzhou Hongji

35/8. Xiangzhou Fayi

35/8. Fahai

35/8. Xiazhou Jingzong

35/8. Fengxiang Jietuo

35/8. Huijian

35/8. Huanglong Weizhong (705–782)

35/8. Xiangzhou Zizhou (bd)

35/8. Wutai Wuming (722-793)

35/8. Cizhou Faru (723–811) (Zhiru)36/9. Yizhou Nanyin (bd) (Jingnan Weizhong)

37/10. Shenzhao (Zhaogong)

37/10. Yizhou Ruyi

37/10. Jianyuan Xuanya

37/10. Suizhou Daoyuan (bd)38/11. Guifeng Zongmi (780–841)

39/12. Chuanao

Inquiry into the Origin of Humanity:

Translation of Tsung-mi's Yüan jen lun

by Peter N. Gregory

Kuroda Institute, University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu, 1995, pp. 43-62.

http://www.questia.com/library/105726420/inquiry-into-the-origin-of-humanity-an-annotated

Inquiry into the Origin of Humanity

by the Sramana Tsung-mi of the Ts'ao-t'ang Temple

on Mount Chung-nan

PREFACE

[707c25] The myriad animate beings teeming with activity— all have their origin. The myriad things flourishing in profusion— each returns to its root. Since there has never been anything that is without a root or origin and yet has branches or an end, how much less could [humanity,] the most spiritual among the three powers [of the cosmos, i. e., heaven, earth, and humanity,] be without an original source? Moreover, one who knows the human is wise, and one who knows himself is illuminated. Now, if I have received a human body and yet do not know for myself whence I have come, how can I know whither I will go in another life, and how can I understand human affairs of the past and present in the world? For this reason, I have studied for several decades without a constant teacher and have thoroughly examined the inner and outer [teachings] in order to find the origin of myself. I sought it without cease until I realized its origin.

[708a2] Now those who study Confucianism and Taoism merely know that, when looked at in proximate terms, they have received this body from their ancestors and fathers having passed down the bodily essence in a continuous series. When looked at in far- reaching terms, the one pneuma of the primordial chaos divided into the dyad of yin and yang, the two engendered the triad of heaven, earth, and human beings, and the three engendered the myriad things. The myriad things and human beings all have the pneuma as their origin. [708a5] Those who study Buddhism just say that, when looked at in proximate terms, they created karma in a previous life and, receiving their retribution in accord with karma, gained this human body. When looked at in far- reaching terms, karma, in

-43-

turn, develops from delusion, and ultimately the ālayavijñāna constitutes the origin of bodily existence. All [i. e., Confucianists, Taoists, and Buddhists] maintain that they have come to the end of the matter, but, in truth, they have not yet exhausted it.

[708a7] Still, Confucius, Lao-tzu, and Śākyamuni were consummate sages who, in accord with the times and in response to beings, made different paths in setting up their teachings. The inner and outer [teachings] complement one another, together benefiting the people. As for promoting the myriad [moral and religious] practices, clarifying cause and effect from beginning to end, exhaustively investigating the myriad phenomena, and elucidating the full scope of birth and arising— even though these are all the intention of the sages, there are still provisional and ultimate [explanations]. The two teachings are just provisional, whereas Buddhism includes both provisional and ultimate. Since encouraging the myriad practices, admonishing against evil, and promoting good contribute in common to order, the three teachings should all be followed and practiced. If it be a matter of investigating the myriad phenomena, fathoming principle, realizing the nature, and reaching the original source, then Buddhism alone constitutes the definitive answer.

[708a13] Nevertheless, scholars today each cling to a single tradition. Even those who follow the Buddha as their teacher are often deluded about the true meaning and therefore, in seeking the origin of heaven, earth, humanity, and things, are not able to find the ultimate source. I will now proceed to investigate the myriad phenomena by relying on the principles of the inner and outer teachings. First, I will advance from the superficial to the profound. For those who study provisional teachings, I will dig out their obstructions, allowing them to penetrate through and reach the ultimate origin. Later, I will demonstrate the meaning of phenomenal evolution by relying on the ultimate teaching. I will join the parts together, make them whole, and extend them back out to the branches ("branches" refers to heaven, earth, humanity, and things). The treatise has four parts and is entitled "Inquiry into the Origin of Humanity."

-44-

I. EXPOSING DELUDED ATTACHMENTS

(For those who study Confucianism and Taoism)

[708a26] The two teachings of Confucianism and Taoism hold that human beings, animals, and the like are all produced and nourished by the great Way of nothingness. They maintain that the Way, conforming to what is naturally so, engenders the primal pneuma. The primal pneuma engenders heaven and earth, and heaven and earth engender the myriad things. [708a28] Thus dullness and intelligence, high and low station, poverty and wealth, suffering and happiness are all endowed by heaven and proceed according to time and destiny. Therefore, after death one again returns to heaven and earth and reverts to nothingness.

[708a29] This being so, the essential meaning of the outer teachings merely lies in establishing [virtuous] conduct based on this bodily existence and does not lie in thoroughly investigating the ultimate source of this bodily existence. The myriad things that they talk about do not have to do with that which is beyond tangible form. Even though they point to the great Way as the origin, they still do not fully illuminate the pure and impure causes and conditions of conforming to and going against [the flow of] origination and extinction. Thus, those who study [the outer teachings] do not realize that they are provisional and cling to them as ultimate.

[708b4] Now I will briefly present [their teachings] and assess them critically. Their claim that the myriad things are all engendered by the great Way of nothingness means that the great Way itself is the origin of life and death, sageliness and stupidity, the basis of fortune and misfortune, bounty and disaster. Since the origin and basis are permanently existent, [it must follow that] disaster, disorder, misfortune, and stupidity cannot be decreased, and bounty, blessings, sageliness, and goodness cannot be increased. What use, then, are the teachings of Lao- tzu and Chuang- tzu? Furthermore, since the Way nurtures tigers and wolves, conceived Chieh and Chou, brought Yen Hui and Jan Ch'iu to a premature end, and brought disaster upon Po I and Shu Ch'i, why deem it worthy of respect?

-45-

[Critique of Spontaneity]

[708b9] Again, their claim that the myriad things are all spontaneously engendered and transformed and that it is not a matter of causes and conditions means that everything should be engendered and transformed [even] where there are no causes and conditions. That is to say, stones might engender grass, grass might engenderhumans, humans engender beasts, and so forth. Further, since they might engender without regard to temporal sequence and arise without regard to due season, the immortal would not depend on an elixir, the great peace would not depend on the sage and the virtuous, and benevolence and righteousness would not depend on learning and practice. For what use, then, did Lao- tzu, Chuang‐ tzu, the Duke of Chou, and Confucius establish their teachings as invariable norms?

[708b13] Again, since their claim that [the myriad things] are engendered and formed from the primal pneuma means that a spirit, which is suddenly born out of nowhere, has not yet learned and deliberated, then how, upon gaining [the body of] an infant, does it like, dislike, and act willfully? If they were to say that one suddenly comes into existence from out of nowhere and is thereupon able to like, dislike, and so forth in accordance with one's thoughts, then it would mean that the five virtues and six arts can all be understood by according with one's thoughts. Why then, depending on causes and conditions, do we study to gain proficiency?

[708b17] Furthermore, if birth were a sudden coming into existence upon receiving the endowment of the vital force and death were a sudden going out of existence upon the dispersion of the vital force, then who would become a spirit of the dead? Moreover, since there are those in the world who see their previous births as clearly as if they were looking in a mirror and who recollect the events of past lives, we thus know that there is a continuity from before birth and that it is not a matter of suddenly coming into existence upon receiving the endowment of the vital force. Further, since it has been verified that the consciousness of the spirit is not cut off, then we know that after death it is not a matter of suddenly going out of existence upon the dispersion of the vital force. This is why the classics contain passages about sacrificing to the dead and beseeching them in prayer, to say nothing of cases, in both

-46-

present and ancient times, of those who have died and come back to life and told of matters in the dark paths or those who, after death, have influenced their wives and children or have redressed a wrong and requited a kindness.

[708b23] An outsider [i. e., a non- Buddhist] may object, saying: If humans become ghosts when they die, then the ghosts from ancient times [until now] would crowd the roads and there should be those who see them— why is it not so? I reply: When humans die, there are six paths; they do not all necessarily become ghosts. When ghosts die, they become humans or other forms of life again. How could it be that the ghosts accumulated from ancient times exist forever? Moreover, the vital force of heaven and earth is originally without consciousness. If men receive vital force that is without consciousness, how are they then able suddenly to wake up and be conscious? Grasses and trees also all receive vital force, why are they not conscious?

[708b28] Again, as for their claim that poverty and wealth, high and low station, sageliness and stupidity, good and evil, good and bad fortune, disaster and bounty all proceed from the mandate of heaven, then, in heaven's endowment of destiny, why are the impoverished many and the wealthy few, those of low station many and those of high station few, and so on to those suffering disaster many and those enjoying bounty few? If the apportionment of many and few lies in heaven, why is heaven not fair? How much more unjust is it in cases of those who lack moral conduct and yet are honored, those who maintain moral conduct and yet remain debased, those who lack virtue and yet enjoy wealth, those who are virtuous and yet suffer poverty, or the refractory enjoying good fortune, the righteous suffering misfortune, the humane dying young, the cruel living to an old age, and so on to the moral being brought down and the immoral being raised to eminence. Since all these proceed from heaven, heaven thus makes the immoral prosper while bringing the moral to grief. How can there be the reward of blessing the good and augmenting the humble, and the punishment of bringing disaster down upon the wicked and affliction upon the full? Furthermore, since disaster, disorder, rebellion, and mutiny all proceed from heaven's mandate, the teachings established by the sages are not right in holding human beings and not heaven responsible and in blaming people and not destiny. Nevertheless, the [ Classic of ]

-47-

Poetry censures chaotic rule, the [ Classic of ] History extols the kingly Way, the [ Book of ] Rites praises making superiors secure, and the [ Classic of ] Music proclaims changing [the people's] manners. How could that be upholding the intention of heaven above and conforming to the mind of creation?

[708c12] The Buddha's teachings proceed from the superficial to the profound. Altogether there are five categories: (1) the Teaching of Humans and Gods, (2) the Teaching of the Lesser Vehicle, (3) the Teaching of the Phenomenal Appearances of the Dharmas within the Great Vehicle, (4) the Teaching That Refutes the Phenomenal Appearances within the Great Vehicle (the above four [teachings] are included within this part), and (5) the Teaching of the One Vehicle That Reveals the Nature (this one [teaching] is included within the third part).

[708c15] 1. The Buddha, for the sake of beginners, at first set forth the karmic retribution of the three periods of time [i. e., past, present, and future] and the causes and effects of good and bad [deeds]. That is to say, [one who] commits the ten evils in their highest degree falls into hell upon death, [one who commits the ten evils] in their lesser degree becomes a hungry ghost, and [one who commits the ten evils] in their lowest degree becomes an animal. [708c17] Therefore, the Buddha grouped [the five precepts] with the five constant virtues of the worldly teaching and caused [beginners] to maintain the five precepts, to succeed in avoiding the three [woeful] destinies, and to be born into the human realm. [708c17] (As for the worldly teaching of India, even though its observance is distinct, in its admonishing against evil and its exhorting to good, there is no difference [from that of China]. Moreover, it is not separate from the five constant virtues of benevolence, righteousness, and so forth, and there is virtuous conduct that should be cultivated. For example, it is like the clasping of the hands together and raising them in this country and the dropping of the hands by the side in Tibet— both are [examples of] propriety. Not killing is benevolence, not stealing is righteousness, not committing adultery is propriety, not lying is trustworthiness, and, by neither drinking wine nor eating meat, the spirit is purified and one increases in wisdom.) [708c20] [One who] cultivates the ten good deeds

-48-

in their highest degree as well as bestowing alms, maintaining the precepts, and so forth is born into [one of] the six heavens of [the realm of] desire. [708c20] [One who] cultivates the four stages of meditative absorption and the eight attainments is bom into [one of] the heavens of the realm of form or the realm of formlessness. [708c21] (The reason gods, [hungry] ghosts, and the denizens of hell are not mentioned in the title [of this treatise] is that their realms, being different [from the human], are beyond ordinary understanding. Since the secular person does not even know the branches, how much less could he presume to investigate the root thoroughly. Therefore, in concession to the secular teaching, I have entitled [this treatise] "An Inquiry into the Origin of Humanity." [However,] in now relating the teachings of the Buddha, it was, as a matter of principle, fitting that I set forth [the other destinies] in detail.) Therefore, [this teaching] is called the Teaching of Humans and Gods. (As for karma, there are three types: I) good, 2) bad, and 3) neutral. As for retribution, there are three periods of time, that is to say, retribution in the present life, in the next life, and in subsequent lives.) According to this teaching, karma constitutes the origin of bodily existence.

[708c23] Now I will assess [this teaching] critically. Granted that we receive a bodily existence in [one of] the five destinies as a result of our having generated karma, it is still not clear who generates karma and who experiences its retribution. [708c25] If the eyes, ears, hands, and feet are able to generate karma, then why, while the eyes, ears, hands, and feet of a person who has just died are still intact, do they not see, hear, function, and move? If one says that it is the mind that generates [karma], what is meant by the mind? If one says that it is the corporeal mind, then the corporeal mind has material substance and is embedded within the body. How, then, does it suddenly enter the eyes and ears and discern what is and what is not of externals? If what is and what is not are not known [by the mind], then by means of what does one discriminate them? Moreover, since the mind is blocked off from the eyes, ears, hands, and feet by material substance, how, then, can they pass in and out of one another, function in response to one another, and generate karmic conditions together? If one were to say that it is just joy, anger, love, and hate that activate the body and mouth and cause them to generate karma, then, since the feelings of joy, anger, and so forth abruptly arise one moment and abruptly perish the next and are of themselves without substance, what can we take as constituting the controlling agent and generating karma?

-49-

[709a4] If one were to say that the investigation should not be pursued in a disconnected fashion like this, but that it is our body‐ and- mind as a whole that is able to generate karma, then, once this body has died, who experiences the retribution of pain and pleasure? If one says that after death one has another body, then how can the commission of evil or the cultivation of merit in the present body- and- mind cause the experiencing of pain and pleasure in another body- and- mind in a future life? If we base ourselves on this [teaching], then one who cultivates merit should be extremely disheartened and one who commits evil should be extremely rejoiceful. How can the holy principle be so unjust? Therefore we know that those who merely study this teaching, even though they believe in karmic conditioning, have not yet reached the origin of their bodily existence.

[709a11] 2. The Teaching of the Lesser Vehicle holds that from [time] without beginning bodily form and cognitive mind, because of the force of causes and conditions, arise and perish from moment to moment, continuing in a series without cease, like the trickling of water or the flame of a lamp. The body and mind come together contingently, seeming to be one and seeming to be permanent. Ignorant beings in their unenlightenment cling to them as a self. [709a14] Because they value this self, they give rise to the three poisons of greed (coveting reputation and advantage in order to promote the self), anger (being angry at things that go against one's feelings, fearing that they will trespass against the self), and delusion (conceptualizing erroneously). The three poisons arouse thought, activating body and speech and generating all karma. Once karma has come into being, it is difficult to escape. Thus [beings] receive a bodily existence (determined by individual karma) of pain and pleasure in the five destinies and a position (determined by collective karma) of superior or inferior in the three realms. In regard to the bodily existence that they receive, no sooner do [beings] cling to it as a self then they at once give rise to greed and so forth, generate karma, and experience its retribution. [709a18] In the case of bodily existence, there is birth, old age, sickness, and death; [beings] die and are born again. In the case of a world, there is formation, continuation, destruction, and emptiness; [worlds] are empty and are formed again.

[709a19] (As for the first formation of the world from the empty kalpa, a verse says that a great wind arises in empty space, its expanse is immeasurable,

-50-

its density is sixteen hundred thousand [leagues], and not even a diamond could harm it. It is called the wind that holds the world together. [709a20] In the light- sound [heaven] a golden treasury cloud spreads throughout the great chiliocosm. Raindrops [as large as] cart hubs come down, but the wind holds it in check and does not let it flow out. Its depth is eleven hundred thousand [leagues]. [709a20] After the diamond world is created, a golden treasury cloud then pours down rain and fills it up, first forming the Brahma [heavens, and then going on to form all the other heavens] down to the Yāma [heaven]. The wind stirs up the pure water, forming Mount Sumeru, the seven gold mountains, and so on. When the sediment forms the mountains, earth, the four continents, and hell, and a salty sea flows around their circumference, then it is called the establishment of the receptacle world. At that time one [period of] increase/ decrease has elapsed. [709a22] Finally, when the merit of [beings in] the second meditation [heaven] is exhausted, they descend to be born as humans. They first eat earth cakes and forest creepers; later the coarse rice is undigested and excreted as waste, and the figures of male and female become differentiated. They divide the fields, set up a ruler, search for ministers, and make distinctions as to the various classes. [This phase] lasts nineteen periods of increase/ decrease. Combined with the previous [period during which the receptacle world was formed] it makes twenty periods of increase/ decrease and is called the kalpa of formation.

[709a23] [I will now] elaborate on [the above]. [The period of time] during the kalpa of empty space is what the Taoists designate as the Way of nothingness. However, since the essence of the Way is tranquilly illuminating and marvellously pervasive, it is not nothingness. Lao- tzu was either deluded about this or he postulated it provisionally to encourage [people] to cut off their human desires. Therefore he designated empty space as the Way. The great wind [that arises] in empty space corresponds to their one pneuma of the primordial chaos; therefore they say that the Way engenders the one. The golden treasury cloud, being the beginning of the pneuma's taking form, is the great ultimate. The rain coming down and not flowing out refers to the congealing of the yin pneuma. As soon as yin and yang blend together, they are able to engender and bring [all things] to completion. From the Brahma Kings' realm down to Mount Sumeru corresponds to their heaven, and the sediment corresponds to the earth, and that is the one engendering the two. The merits [of those in] the second meditation [heaven] being exhausted and their descending to be bom refers to human beings, and that is the two engendering the three, and the three powers thus being complete. From the earth cakes to the various classes is the three engendering the myriad things. This corresponds to [the time] before the three kings when people lived in caves, ate in the wilderness, did not yet have the transforming power of fire, and so on. [709a27]

-51-

It is only because there were no written records at the time that the legendary accounts of people of later times were not clear; they became increasingly confused, and different traditions wrote up diverse theories of sundry kinds. Moreover, because Buddhism penetrates and illuminates the great chiliocosm and is not confined to China, the writings of the inner and outer teachings are not entirely uniform.

[709b1] "Continuation" refers to the kalpa of continuation; it also lasts for twenty [periods of] increase/ decrease. "Destruction" refers to the kalpa of destruction ; it also lasts for twenty [periods of] increase/ decrease. During the first nineteen [periods of] increase/ decrease sentient beings are destroyed; during the last [period of] increase/ decrease the receptacle world is destroyed. That which destroys them are the three cataclysms of fire, water, and wind. "Empty" refers to the kalpa of emptiness; it also lasts for twenty [periods of] increase/ decrease. During [the kalpa of] emptiness there is neither [receptacle] world nor sentient beings.)

[709b2] Kalpa after kalpa, birth after birth, the cycle does not cease; it is without end and without beginning, like a well wheel drawing up [water]. (Taoism merely knows of the single kalpa of emptiness when the present world had not yet been formed. It calls it nothingness, the one pneuma of the primordial chaos, and so forth, and designates it as the primeval beginning. It does not know that before [the kalpa of] empty space there had already passed thousands upon thousands and ten- thousands upon ten- thousands of [kalpas of] formation, continuation, destruction, and emptiness, which, on coming to an end, began again. Therefore we know that within the teaching of Buddhism even the most superficial Teaching of the Lesser Vehicle already surpasses the most profound theories of the outer canon.) All this comes about from [beings] not understanding that the body is from the very outset not the self. "Is not the self' refers to the fact that the body originally takes on phenomenal appearance because of the coming together of form and mind.

[709b6] If we now push our analysis further, form is comprised of the four great elements of earth, water, fire, and wind, whereas mind is comprised of the four aggregates of sensation (that which receives agreeable and disagreeable things), conceptualization (that which forms images), impulses (that which creates and shifts and flows from moment to moment), and consciousness (that which discriminates). If each of these were a self, then they would amount to eight selves. How much more numerous would [the selves] be among the earthly element! That is to say, each one of the three hundred sixty bones is distinct from the others; skin, hair, muscles, flesh, liver, heart, spleen, and kidneys are each not the other. Each of the various

-52-

mental functions are also not the same; seeing is not hearing, joy is not anger, and so on and so forth to the eighty- four thousand defilements. Since there are so many things, we do not know what to choose as the self. If each of them were a self, then there would be hundreds upon thousands of selves, and there would be the utter confusion of many controlling agents within a single body. Furthermore, there is nothing else outside of these [components]. When one investigates them inside and out, a self cannot be found in any of them. One then realizes that the body is just the phenomenal appearance of the seeming combination of various conditions and that there has never been a self.

[709b16] On whose account does one have greed and anger? On whose account does one kill, steal, give [alms], and maintain the precepts (knowing the truth of suffering)? Then, when one does not obstruct the mind in good and bad [deeds] that have outflows in the three realms (the truth of cutting off the accumulation [of suffering]) and only cultivates the wisdom of the view of no- self (the truth of the path), one thereby cuts off greed and so forth, puts a stop to all karma, realizes the reality of the emptiness of self (the truth of extinction), until eventually one attains arhatship: as soon as one makes one's body as ashes and extinguishes thought, one cuts off all suffering. According to this teaching, the two dharmas of form and mind, as well as greed, anger, and delusion, constitute the origin of the body of senses and the receptacle world. There has never been nor will ever be anything else that constitutes the origin.

[709b21] Now I will assess [this teaching] critically. That which constitutes the source of bodily existence in the experiencing of repeated births and the accumulation of numerous life- times must, in itself, be without interruption. [However], the present five [sense] consciousnesses do not arise in the absence of conditions (the sense organs, sense objects, and so forth constitute the conditions), there are times when consciousness does not operate (during unconsciousness, deep sleep, the attainment of extinction, the attainment of non- consciousness, and among the non- conscious gods), and the gods in the realm of formlessness are not comprised of the four great elements. How, then, do we hold on to this bodily existence life- time after life- time without ceasing? Therefore we know that those who are devoted to this teaching have also not yet reached the origin of bodily existence.

-53-

[3. The Teaching of the Phenomenal Appearances of the Dharmas] [709b26] 3. The Teaching of the Phenomenal Appearances of the Dharmas within the Great Vehicle holds that all sentient beings from [time] without beginning inherently have eight kinds of consciousness. Of these, the eighth— the ālayavijñāna— is the fundamental basis. It instantaneously evolves into the body of the senses, the receptacle world, and the seeds, and transforms, generating the [other] seven consciousnesses. All [eight consciousnesses] evolve and manifest their own perceiving subject and perceived objects, none of which are substantial entities.

[709c1] How do they evolve? [The Ch'eng wei- shih lun ] says: "Because of the influence of the karmically conditioned predispositions of the discrimination of self and things [in the ālayavijñāna], when the consciousnesses are engendered [from the ālayavijñāna], they evolve into the semblance of a self and things." The sixth and seventh consciousness, because they are obscured by ignorance, "consequently cling to [their subjective and objective manifestations] as a substantial self and substantial things."

[709c3] "It is like the case of being ill (in grave illness the mind is befuddled and perceives people and things in altered guise) or dreaming (the activity of dreaming and what is seen in the dream may be distinguished). Because of the influence of the illness or dream, the mind manifests itself in the semblance of the phenomenal appearance of a variety of external objects." When one is dreaming, one clings to them as substantially existing external things, but, as soon as one awakens, one realizes that they were merely the transformations of the dream. One's own bodily existence is also like this: it is merely the transformation of consciousness. Because [beings] are deluded, they cling to [these transformations] as existing self and objects, and, as a result of this, generate delusion and create karma, and birth- and- death is without end (as amply explained before). As soon as one realizes this principle, one understands that our bodily existence is merely the transformation of consciousness and that consciousness constitutes the root of bodily existence ([this teaching is of] non- final meaning, as will be refuted later).

[709c9] 4. The Teaching of the Great Vehicle That Refutes Phenomenal Appearances refutes the attachment to the phenomenal appearances of the dharmas in the previous [teachings of] the Great

-54-

and Lesser Vehicles and intimates the principle of the emptiness and tranquility of the true nature in the later [teaching]. [709c10] (Discussions that refute phenomenal appearances are not limited to the various sections of the Perfection of Wisdom but pervade the scriptures of the Great Vehicle. [Although] the previous three teachings are arranged on the basis of their temporal order, [since] this teaching refutes them in accordance with their attachments, it [was taught] without a fixed time period. Therefore Nāgārjuna posited two types of wisdom: the first is the common, and the second is the distinct. The common refers to [that which the followers of] the two vehicles alike heard, believed, and understood, because it refuted the attachment to dharmas of [the followers of] the two vehicles. The distinct refers to [that which] only the bodhisattvas understood, because it intimated the Buddha- nature. [709c12] Therefore the two Indian śāstra- masters Śīlabhadra and Jñānaprabha each categorized the teachings according to three time periods, but in their placing of this teaching of emptiness, one said that it was before [the Teaching of] the Phenomenal Appearances of the Dharmas of consciousness- only, while the other said that it was after. Now I will take it to be after.)

[709c13] Wishing to refute [the Teaching of the Phenomenal Appearances of the Dharmas], I will first assess [the previous teaching] critically. Granted that the object that has evolved is illusory, how, then, can the consciousness that evolves be real? If one says that one exists and the other does not (from here on their analogy will be used to refute them), then the activity of dreaming and the things seen [in the dream] should be different. If they are different, then the dream not being the things [seen in the dream] and the things [seen in the dream] not being the dream, when one awakens and the dream is over, the things [seen in the dream] should remain. Again, the things [seen in the dream], if they are not the dream, must be real things, but how does the dream, if it is not the things [seen in the dream], assume phenomenal appearance? Therefore we know that when one dreams, the activity of dreaming and the things seen in the dream resemble the dichotomy of seeing and seen. Logically, then, they are equally unreal and altogether lack existence. [709c19] The various consciousnesses are also like this because they all provisionally rely on sundry causes and conditions and are devoid of a nature of their own. Therefore the Middle Stanzas says: "There has never been a single thing that has not been born from causes and conditions. Therefore there is nothing that is not empty." And further: "Things born by causes and conditions I declare to be empty." The Awakening of Faith says: "It is only on the basis of deluded thinking that all things have differentiations.

-55-

If one is free from thinking, then there are no phenemenal appearances of any objects." The [ Diamond ] S ū tra says: "All phenomenal appearances are illusory." Those who are free from all phenomenal appearances are called Buddhas. (Passages like these pervade the canon of the Great Vehicle.) Thus we know that mind and objects both being empty is precisely the true principle of the Great Vehicle. If we inquire into the origin of bodily existence in terms of this [teaching], then bodily existence is from the beginning empty, and emptiness itself is its basis.

[709c26] Now I will also assess this Teaching [That Refutes Phenomenal Appearances] critically. If the mind and its objects are both nonexistent, then who is it that knows they do not exist? Again, if there are no real things whatsoever, then on the basis of what are the illusions made to appear? Moreover, there has never been a case of the illusory things in the world before us being able to arise without being based on something real. [709c29] If there were no water whose wet nature were unchanging, how could there be the waves of illusory, provisional phenomenal appearances? If there were no mirror whose pure brightness were unchanging, how could there be the reflections of a variety of unreal phenomena? Again, while the earlier statement that the activity of dreaming and the dream object are equally unreal is indeed true, the dream that is illusory must still be based on someone who is sleeping. Now, granted that the mind and its objects are both empty, it is still not clear on what the illusory manifestations are based. Therefore we know that this teaching merely destroys feelings of attachment but does not yet clearly reveal the nature that is true and numinous. Therefore the Great Dharma Drum S ū tra says: "All emptiness sūtras are expositions that have a remainder." ("Having a remainder" means that the remaining meaning has not yet been fully expounded.) The Great Perfection of Wisdom S ū tra says: "Emptiness is the first gate of the Great Vehicle."

[710a6] When the above four teachings are compared with one another in turn, the earlier will be seen to be superficial and the later profound. If someone studies [a teaching] for a time, and oneself realizes that it is not yet ultimate, [that teaching] is said to be superficial. But if one clings to [such a teaching] as ultimate, then one is said to be partial. Therefore it is in terms of the people who study them that [the teachings] are spoken of as partial and superficial.

-56-

III. DIRECTLY REVEALING THE TRUE SOURCE

(The true teaching of the ultimate meaning of the Buddha.)

[5. The Teaching That Reveals the Nature]

[710a11] 5. The Teaching of the One Vehicle That Reveals the Nature holds that all sentient beings without exception have the intrinsically enlightened, true mind. From [time] without beginning it is permanently abiding and immaculate. It is shining, unobscured, clear and bright ever- present awareness. It is also called the Buddha- nature and it is also called the tathāgatagarbha. From time without beginning deluded thoughts cover it, and [sentient beings] by themselves are not aware of it. Because they only recognize their inferior qualities, they become indulgently attached, enmeshed in karma, and experience the suffering of birth- and- death. The great enlightened one took pity upon them and taught that everything without exception is empty. He further revealed that the purity of the numinous enlightened true mind is wholly identical with all Buddhas.

[710a16] Therefore the Hua- yen S ū tra says: "Oh sons of the Buddha, there is not a single sentient being that is not fully endowed with the wisdom of the Tathāgata. It is only on account of their deluded thinking and attachments that they do not succeed in realizing it. When they become free from deluded thinking, the all‐ comprehending wisdom, the spontaneous wisdom, and the unobstructed wisdom will then be manifest before them." [710a19] [The sūtra] then offers the analogy of a single speck of dust containing a sūtra roll [as vast as] the great chiliocosm. The speck of dust represents sentient beings, and the sūtra represents the wisdom of the Buddha. [710a20] [The Hua- yen S ū tra ] then goes on to say: "At that time the Tathāgata with his unobstructed pure eye of wisdom universally beheld all sentient beings throughout the universe and said: 'How amazing! How amazing! How can it be that these sentient beings are fully endowed with the wisdom of the Tathāgata and yet, being ignorant and confused, do not know it and do not see it? I must teach them the noble path enabling them to be forever free from deluded thinking and to achieve for themselves the seeing of the broad and vast wisdom of the Tathāgata within themselves and so be no different from the Buddhas."'

[710a24] [I will now] elaborate on [this teaching]. Because for numerous kalpas we have not encountered the true teaching, we have not known how to turn back and find the [true] origin of our

-57-

bodily existence but have just clung to illusory phenomenal appearances, heedlessly recognizing [only] our unenlightened nature, being born sometimes as an animal and sometimes as a human. When we now seek our origin in terms of the consummate teaching, we will immediately realize that from the very outset we are the Buddha. Therefore, we should base our actions on the Buddha's action and identify our minds with Buddha's mind, return to the origin and revert to the source, and cut off our residue of ignorance, reducing it and further reducing it until we have reached the [state of being] unconditioned. Then our activity in response [to other beings] will naturally be [as manifold as] the sands of the Ganges— that is called Buddhahood. You should realize that delusion and enlightenment alike are [manifestations of] the one true mind. How great the marvelous gate! Our inquiry into the origin of humanity has here come to an end.

[710a29] (In the Buddha's preaching of the previous five teachings, some are gradual and some are sudden. In the case of [sentient beings of] medium and inferior capacity, [the Buddha] proceeded from the superficial to the profound, gradually leading them forward. He would initially expound the first teaching [of Humans and Gods], enabling them to be free from evil and to abide in virtue; he would then expound the second and third [teachings of the Lesser Vehicle and the Phenomenal Appearances of the Dharmas], enabling them to be free from impurity and to abide in purity; he would finally discuss the fourth and fifth [teachings], those that Refute Phenomenal Appearances and Reveal the Nature, subsuming the provisional into the true, [enabling them] to cultivate virtue in reliance on the ultimate teaching until they finally attain Buddhahood. [710b2] In the case of [sentient beings of] wisdom of the highest caliber, [the Buddha] proceeded from the root to the branch. That is to say, from the start he straightaway relied on the fifth teaching to point directly to the essence of the one true mind. When the essence of the mind had been revealed, [these sentient beings] themselves realized that everything without exception is illusory and fundamentally empty and tranquil; that it is only because of delusion that [such illusory appearances] arise in dependence upon the true [nature]; and that it is [thus] necessary to cut off evil and cultivate virtue by means of the insight of having awakened to the true, and to put an end to the false and return to the true by cultivating virtue. When the false is completely exhausted and the true is present in totality, that is called the dharmakāya Buddha.)

-58-

IV. RECONCILING ROOT AND BRANCH

[The Process of Phenomenal Evolution]

[710b4] (When [the teachings that] have been refuted previously are subsumed together into the one source, they all become true.) [710b5] Although the true nature constitutes the [ultimate] source of bodily existence, its arising must surely have a causal origin, for the phenomenal appearance of bodily existence cannot be suddenly formed from out of nowhere. It is only because the previous traditions had not yet fully discerned [the matter] that I have refuted them one by one. Now I will reconcile root and branch, including even Confucianism and Taoism.

[710b7] (At first there is only that which is set forth in the fifth teaching of the Nature. From the following section on, [each] stage [in the process of phenomenal evolution] will be correlated with the various teachings, as will be explained in the notes.) At first there is only the one true numinous nature, which is neither born nor destroyed, neither increases nor decreases, and neither changes nor alters. [Nevertheless], sentient beings are [from time] without beginning asleep in delusion and are not themselves aware of it. Because it is covered over, it is called the tathāgatagarbha, and the phenomenal appearance of the mind that is subject to birth- and- death comes into existence based on the tathāgatagarbha.

[710b10] (From here on corresponds to the fourth teaching, which is the same as [that which] Refuted the Phenomenal Appearances that are subject to birth- and- death.) The interfusion of the true mind that is not subject to birth- and- death and deluded thoughts that are subject to birth‐ and- death in such a way that they are neither one nor different is referred to as the ālayavijñāna. This consciousness has the aspects both of enlightenment and unenlightenment.

[710b13] (From here on corresponds to that which was taught in the third teaching of the Phenomenal Appearances of the Dharmas.) When thoughts first begin to stir because of the unenlightened aspect [of the ālayavijñāna], it is referred to as the phenomenal appearance of activity. Because [sentient beings] are also unaware that these thoughts are from the beginning nonexistent, [the ālayavijñāna] transforms into the manifestation of the phenomenal appearance of a perceiving subject and its perceived objects. Moreover, being unaware that these objects are deludedly manifested from their own mind, [sentient beings] cling to them as fixed existents, and that is referred to as attachment to things.

-59-

[710b16] (From here on corresponds to that which was taught in the second teaching of the Lesser Vehicle.) Because they cling to these, [sentient beings] then perceive a difference between self and others and immediately form an attachment to the self. Because they cling to the phenomenal appearance of a self, they hanker after things that accord with their feelings, hoping thereby to enhance themselves, and have an aversion to things that go against their feelings, fearing that they will bring harm to themselves. Their foolish feelings thus continue to escalate ever further.

[710b19] (From here on corresponds to that which was taught in the first teaching of Humans and Gods.) Therefore, when one commits [evil deeds] such as murder or theft, one's spirit, impelled by this bad karma, is born among the denizens of hell, hungry ghosts, or animals. Again, when one who dreads suffering or is virtuous by nature practices [good deeds] such as bestowing alms or maintaining the precepts, one's spirit, impelled by this good karma, is transported through the intermediate existence into the mother's womb (from here on corresponds to that which was taught in the two teachings of Confucianism and Taoism) and receives an endowment of vital force and material substance. ([This] incorporates their statement that the vital force constitutes the origin.)

[710b23] The moment there is vital force, the four elements are fully present and gradually form the sense organs; the moment there is mind, the four [mental] aggregates are fully present and form consciousness. When ten [lunar] months have come to fruition and one is born, one is called a human being. This refers to our present body- and- mind. Therefore we know that the body and mind each has its origin and that as soon as the two interfuse, they form a single human. It is virtually the same as this in the case of gods, titans, and so forth.

[710b26] While one receives this bodily existence as a result of one's directive karma, one is in addition honored or demeaned, impoverished or wealthy, long or short lived, ill or healthy, flourishes or declines, suffers or is happy, because of one's particularizing karma. That is to say, when the respect or contempt shown [to others] in a previous existence serves as the cause, it determines the result of one's being honored or demeaned in the present, and so on and so forth to the humane being long- lived, the murderous short- lived, the generous wealthy, and the miserly impoverished. The various types of individual retribution [are so diverse that they] could not be fully enumerated. Therefore, in this bodily existence,

-60-

while there may be cases of those who are without evil and even so suffer disaster, or those who are without virtue and even so enjoy bounty, or who are cruel and yet are long- lived, or who do not kill and yet are short- lived, all have been determined by the particularizing karma of a previous lifetime. Therefore the way things are in the present lifetime does not come about from what is done spontaneously. Scholars of the outer teachings do not know of previous existences but, relying on [only] what is visible, just adhere to their belief in spontaneity. ([This] incorporates their statement that spontaneity constitutes the origin.)

[710c5] Moreover, there are those who in a previous life cultivated virtue when young and perpetuated evil when old, or else were evil in their youth and virtuous in their old age; and who hence in their present lifetime enjoy moderate wealth and honor when young and suffer great impoverishment and debasement when old, or else experience the suffering of impoverishment in youth and enjoy wealth and honor in old age. Thus scholars of the outer teachings just adhere to their belief that success and failure are due to the sway of fortune. ([This] incorporates their statement that everything is due to the mandate of heaven.)

[710c8] Nevertheless, the vital force with which we are endowed, when it is traced all the way back to its origin, is the primal pneuma of the undifferentiated oneness; and the mind that arises, when it is thoroughly investigated all the way back to its source, is the numinous mind of the absolute. In ultimate terms, there is nothing outside of mind. The primal pneuma also comes from the evolution of mind, belongs to the category of the objects that were manifested by the previously evolved consciousness, and is included within the objective aspect of the ālaya[ vijñāna]. From the phenomenal appearance of the activation of the very first thought, [the ālayavijñāna] divides into the dichotomy of mind and objects. The mind, having developed from the subtle to the coarse, continues to evolve from false speculation to the generation of karma (as previously set forth). Objects likewise develop from the fine to the crude, continuing to evolve from the transformation [of the ālayavijñāna] into heaven and earth. (The beginning for them starts with the grand interchangeability and evolves in five phases to the great ultimate. The great ultimate [then] produces the two elementary forms. Even though they speak of spontaneity and the great Way as we here speak of the true nature, they are actually nothing but the subjective aspect of the evolution [of the ālayavijñāna] in a single moment of thought; even though they talk of the primal pneuma as we here

-61-

speak of the initial movement of a single moment of thought, it is actually nothing but the phenomenal appearance of the objective world.) When karma has ripened, then one receives one's endowment of the two vital forces from one's father and mother, and, when it has interfused with activated consciousness, the human body is completely formed. According to this, the objects that are transformed from consciousness immediately form two divisions: one division is that which interfuses with consciousness to form human beings, while the other division does not interfuse with consciousness and is that which forms heaven and earth, mountains and rivers, and states and towns. The fact that only humans among the three powers [of heaven, earth, and humanity] are spiritual is due to their being fused with spirit. This is precisely what the Buddha meant when he said that the internal four elements and the external four elements are not the same.

[710c21] How pitiable the confusion of the false attachments of shallow scholars! Followers of the Way, heed my words: If you want to attain Buddhahood, you must thoroughly discern the coarse and the subtle, the root and the branch. Only then will you be able to cast aside the branch, return to the root, and turn your light back upon the mind source. When the coarse has been exhausted and the subtle done away with, the numinous nature is clearly manifest and there is nothing that is not penetrated. That is called the dharmakāya and sambhogakāya. Freely manifesting oneself in response to beings without any bounds is called the nirmānakāya Buddha.

-62-

Miklós Pál

A Csan buddhizmus és a történetírás

(1995)

In: Tus és ecset: Kínai művelődéstörténeti tanulmányok, Budapest, 1996, 135-141. oldal

Idestova két évtizede, hogy megkíséreltem a Chan (japán kiejtésben Zen) buddhizmusnak a művészetekre gyakorolt termékenyítő hatását leírni. (A Zen és a művészetek, Magvető, Bp., 1978.) A könyvecskében röviden összefoglaltam a kínai eredet történetét is, a Chan szekta megszületését és kibontakozását kínai földön. Ahogyan akkor a Chan irodalma tudni engedte: a pátriárkák történetét, az indiai Bódhidharmától kezdve Hui-neng-ig, a Hatodikig s azután néhány híres mesterről is szóltam (Lin-ji-ről kicsit bővebben). Ilyen bonyolult históriáról röviden szólni nehéz, az ember óvatos megfogalmazásokkal segít magán. Nem is bántam meg óvatosságomat. A Chan történetének tudományos feldolgozásában ugyanis az utóbbi évtizedekben érdekes új eredmények születtek. (Egyik ilyenről szól az előző írás: egy korai Chan-történetről és szerzője sorsáról: A Csan nem-hivatalos története) Ha a Chan történetéről kialakult nézeteinket nem is kell gyökeresen megváltoztatni, néhány ponton bizony érdekesen módosul a kép.

A Chan írásellenessége az első pont, amely revízióra szorul. Hiábavalónak bizonyul a népszerű versike is, ami az írás ellen szól, tévedés a Japánban is, Nyugaton is elterjedt közhely az írott tradíciók megvetéséről, mert kemény történelmi tények, régészeti leletek tanúskodnak az ellenkezőjéről. A Chan kialakulása korából származó történeti feljegyzéseket és dogmatikai írásokat tártak fel korunk régészei, olykor szorgalmas munkával, olykor a véletlen segítségével, hogy azután filológusok és történészek jussanak ezekből a leletekből meglepő következtetésekre.

A történet régen kezdődött: Stein Aurél 1907-ben felfedezte a Dun-huang-ban befalazott könyvtárcellát (és ahogyan kínai tudósok írják, „kirabolta” azt). Stein leletét jórészt a British Múzeumba vitték. A következő évben érkezett Dun-huang-ba Paul Pelliot, a kitűnő francia tudós, ő már roppant nyelvtudása birtokában válogatott a cella kézirataiból – az ő leletei Párizsba kerültek. (Jutott még anyag Peking könyvtárába is.) Ezek a becses kéziratok azonban sok évig érintetlenül hevertek a nyugati sinológia két fővárosában – nem volt, aki feldolgozza őket. Giles katalógusa a londoni anyagról csak 1957-ben, a párizsi katalógus pedig csak 1970-ben jelent meg. A nagyon szívós tudósoknak azért sikerült már korábban is hozzájutni ezekhez. Hu Shi, a jeles kínai tudós még 1932-ben publikált tanulmányában kezdte el a Chan történetének revízióját. Ezt az tette lehetővé, hogy 1928-tól megjelentek a nagy buddhista kánon japáni összkiadásában, a Taishonak nevezett gyűjtemény 48. kötetétől kezdve a Chan művei is, köztük a Dunhuang-ban felfedezettek. Akkoriban azonban csak kevesen figyeltek fel erre. D. T. Suzuki közéjük tartozott. A háború után megélénkült a kutatás, ennek jeleként az úttörők vitája következett, nagyon fontos kérdésekről: Hu Shi szerint a Chan története csak egy a vallási mozgalmak közül a Tang korban, Suzuki azonban a Chan történelmen túlmutató jelentőségét vallja s az előbbi nézet képviselőit redukcionistáknak ítéli. Ez a vita azóta is tart, mert a lassan egyre szélesebb körben elérhető dunhuangi leletek egyre több tudós kutatásait alapozták meg, elsősorban a japánokét, majd pedig az amerikaiakét. Ha a megoszlás nem is egyértelmű, nyilvánvaló, hogy a japánok közt vannak főként a hívők, s az ő számukra a Chan története nem ugyanazt jelenti, amit a „hitetlen” nyugatiaknak.

Nemcsak Dunhuang tartogatott ilyen kincseket, hanem japán és koreai kolostorok is. A legfontosabb ezek közt az a szektatörténet, amely 952-ben íródott Kínában, a Zu-tang-ji (Ősök Csarnoka Gyűjtemény); ez kevéssel leíratása után egy példányban elkerült Koreába, ott 1245-ben kinyomtatták ugyan, de századunkra már csak a koreai Haeinsa kolostor dúckészlete maradt fenn, ennek lenyomatát publikálták 1972-ben. Szerencsére Yanagida Seizan professzor már az ötvenes években hozzájutott egy régi másolatához. Ettől az időtől fogva indult meg újult erővel az a kutatás, amely napjainkra jelentősen átformálta a Chan korai időszakáról addig élő képünket. Akkor még nagyon nehéz körülmények között: Yanagida professzor egy interjúban meséli el, hogy miként másolta le az egész szöveget először magának, azután, amikor már sokszorosító géphez lehetett jutni, a sokszorosítás céljára – hogy egyetemi szemináriumán dolgozhassa fel a régi szöveget.

Eszerint a 9. században – amint Yanagida professzor fogalmaz – volt buddhizmus, de nem létezett még Chan-szekta. Voltak kolostorok, szerzetesek, de azok még tanítók nélkül keresték az igaz utat, volt kérdés és példázat, de mindenki a maga útját járta. A fényes és virágzó Chan-kolostorok megléte kétszáz évvel korábban – egyszerűen koholmány. Amint az előkerült kéziratok tanúsítják, a Hatodik Pátriárkából egy késői tanítvány, Shen-hui iratai formáltak rendkívüli figurát és követőiből déli iskolát. Ilyen módon maradt Shen-xiu (az emlékezetes verspárbaj vesztese) az északiak reprezentánsa. Ez azonban még a 8. században történt, a két szekta különállásának ténye csak később kanonizálódott: 1004-ben készült a Chuan-deng-lu (Kézről-kézre járó Mécses Feljegyzés), ez az anekdotikus történet-sor, amelyet napjainkban a Chan hagyomány alaptípusának tartanak, s ettől kezdve a Chan-történetek és más feljegyzések a császári udvar befolyása és ellenőrzése alatt készültek. Ez az időszak tehát a Chan kínai beilleszkedésének ideje: a Song kor az érett Chan korszaka.

Ezek a kutatások az egész Chan-történet korszakolását is lehetővé tették. Ma lényegében három korszakot különböztetünk meg a kínai Chan életében: a kezdetek korát a Pátriárka-Chan vagy klasszikusok korának nevezhetjük (kb. 500–700), a második szakaszt illeti a Vernakuláris Chan elnevezés (az akkori irodalom nyelve okán) s ez az érett Tang korban virágzik ki (kb. 700–1000), végül az utolsó kínai korszak a Mécses Chan nevet érdemli (fent említett Mécses Feljegyzések nyomán), amely már a Song korban zajlik le (kb. 1000–1300). Az utolsó korszak után Kínában lehanyatlik a Chan-kultusz, illetve ekkor kerül át Japánba és ott új felvirágzása kezdődik. A Mécses-korszakot irodalmi korszak néven is emlegetik, minthogy az ekkor keletkezett művek és a korábbi művek ekkori redakciói határozott irodalmi igénnyel készültek, ellentétben a Vernakuláris korszak feljegyzéseivel. A korszakot azért is lehet elkülöníteni az előzőktől, mert mostanig jórészt csak az akkor, nyomtatásban megjelent munkák adták az anyagát, mostanában viszont előkerültek a dunhuangi cellában megőrzött, tehát minden változtatás és javítás nélküli, a Vernakuláris korból származó szövegek kéziratai (és tibeti fordításai).

Elsősorban Yanagida professzornak, a Kyotóban működő Iriya Yoshitaka (Hanazono Egyetem) professzornak és az általuk vezetett kutatócsoportoknak köszönhető azoknak a modern európai filológiára alapozott textológiai módszereknek a kidolgozása és alkalmazása, amely aztán a fiatalabb amerikai és francia tudósoknak is egyengette az útját a Chan-buddhizmus kutatásában. (A franciák kitűnő intézetet működtetnek Kyotóban, publikációjuk a Cahiers d'Extrême Asie, amelynek 7. száma szolgáltatja az én információimat is.)

*

A fölélénkült és termékeny Chan-kutatások érzékeltetésére bemutatok egy régóta ismert szútra-kommentárt, amely önmagában is ékes bizonyítéka annak, hogy keletkezésének kora a Chan kialakulásának (a Vernakuláris Chan periódusnak) ítélhető, s egyben szépen illusztrálja is azt. Gui-feng Zong-mi (780–841) munkájáról van szó, amely 828 körül keletkezett és beszédes címet visel: A Tökéletes Megvilágosodás Szútrával a Visszavonulás Művelésére Kézikönyve (Yuan-jue jing dao-cheng yi). Zong-mi fiatal szerzetesként olvasott bele egy példányába a Tökéletes Megvilágosodás Szútrának egy tisztviselő házánál tartott házi ájtatosságon, és néhány sora is olyan hatással volt rá, hogy húsz évig csak ezzel fog lalkozott. Hamarosan úgy ítélte, hogy ez a szútra fontosabb, mint minden addig megismert mű. Tanulmányozását hamarosan kommentárokban gyümölcsöztette.

Zong-mi nem tudta, hogy a Tökéletes Megvilágosodás Szútra apokrif munka (ezt csak a modern valláskritika derítette ki). Többre becsülte még a Hua-yan Szútránál is, amely addigi fő olvasmánya volt és amely akkor a kínai buddhisták körében a legelterjedtebb, legtöbbre becsült szútra volt. Buzgón és szorgosan írta kommentárjait, amelyekből kitűnik, hogy a Chan hívei is az általánosan elterjedt kínai buddhista szertartásokkal körítve munkálkodtak az üdvösség elnyerésén.

Zong-mi műve voltaképp egy visszavonulási bevezető szertartás forgatókönyve. Ez a visszavonulás – lehet 80, illetve 120 napos – afféle lelkigyakorlat; a résztvevők a szertartás után magányos elmélkedéssel töltik idejüket. Ez a lelkigyakorlat fizikai erőfeszítésnek sem kicsiny: naponta hat alkalommal (napnyugta, este, éjfél, éjjel, hajnal, dél) végzik a teljes szertartást, amelynek programja a következő:

A liturgia maga három fő részből áll: az első az invokáció, amelynek 8 része van:

1. felajánlás (füstölő, virágok elhelyezése féltérden),

2. magasztalás (ének szútrákból, öt leborulás),

3. hódolat (megszólítások, leborulások),

4. bűnbánat (a hat érzék bűnei; füstölő, virágok elhelyezése, koncentrálás a 3 kincsre, meghajlás),

5. könyörgés Buddhához (vers recitálása, meghajlás háromszor),

6. örvendezés mások megvilágosodásán (meghajlás a 3 kincs előtt),

7. felajánlás (bűnbánattal szerzett érdemek felaján lása minden érző lényért, meghajlás háromszor),

8. fogadalmak (meghajlás Vairocsána előtt).

A második rész a liturgikus recitálás (a Tökéletes Megvilágosodás szútra részleteit recitálják, miközben körüljárják a csarnokot). Fohász Amitábhához.

A harmadik rész az ülve elmélkedés.

Ehhez a liturgikus programhoz hozzá kell képzelnünk a csarnokot, amelyet Amitábha és Vairocsána képmásai, illetve szobrai díszítenek, és az egyforma csuhát viselő, kopasz szerzeteseket. Ülő bútor nincsen a csarnokban, legfeljebb egy emelvény a liturgiát vezető mester részére; az ülőpárnákat a padlóra teszik, vannak még virágvázák, gyertyák a füstölőrudacskák meggyújtására, homokkal teli bronzedény, amelynek homokjába a füstölőrudacskákat szúrják bele.

A liturgikus szertartás minden mozzanatának megvan a sajátos jelentése az üdvhöz vezető úton: az első felajánlás a fösvénységtől óv meg, a magasztalás a rágalomtól, a hódolat a gőgtől, a bűnbánat a csapásoktól és a bűnhődéstől, a könyörgés a káromlástól, az örvendezés az irigységtől, a második felajánlás az aljasságtól és így tovább a másik oldalon: ott is megvan minden aktusnak a pontosan megjelölt jótékony hatása. Zong-mi leírásában mindenképp.

Peter N. Gregory, aki Zong-mi traktátusát gondosan elemezte, utal arra, hogy a dokumentumok szerint ilyen szertartások éltek még a későbbi korokban is, évszázadokkal később is Kína földjén a Chan-szektához tartozó buddhista kolostorokban, és Japánba átkerülve, az ottani Zen-kolostorokban is. Érdekes adalék, hogy személyesen találkozott olyan szerzetessel, aki Tajvanon Zong-mi szertartásrendjének rövidített változatával készült visszavonuláson vett részt napjainkban.

*

Ha a Dun-huang-ban előkerült, hiteles és épségben megőrzött kéziratok, valamint a nyomukban fellendülő Chan-történeti kutatások arra is intenek, hogy kissé szerényebben, lassú, fokozatos fejlődésnek kell ezentúl tekintenünk ennek a nagy hatású buddhista szektának a kibontakozását, ez azért nem jelenti az eddigi kép, a régi történetírás (és szektán belüli történetírás) elértéktelenedését. Talán el fogja veszíteni az a régi kép a maga túlságosan is ragyogó fényeit, a pompás és akadálytalan diadalmenetnek azt a színpadiasságát, amely eddig övezte – s nemcsak a hívei, hanem történészei szemében is. Viszont az új kép nyerni fog ezeknek a talmi díszeknek a lehántásával: a történészek szemében hitelességében, a hívők szemében pedig annak újra igazolásában, hogy semmiféle értékes emberi gondolat – még vallási igazság sem – juthat könnyen győzelemre.