ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

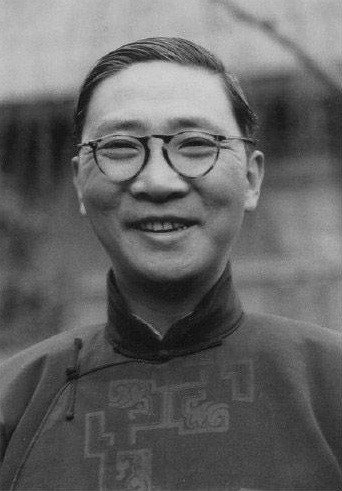

John C. H. Wu (John Ching Hsiung Wu, 1899-1986)

[吳經熊 Wu Ching-hsiung / Wu Jingxiong]

Wu Ching-hsiung (1899-1986), known as Dr. John C. H. Wu, was an author, lawyer, juristic philosopher, educator, and prominent Catholic layman. He was president of the Special High Court at Shanghai, vice chairman of the Legislative Yuan’s constitution drafting committee, founder of the T’ien Hsia Monthly, translator of the Psalms and the New Testament, and Chinese minister to the Holy See in Rome (1947-48).

John C. H. Wu was born in Ningbo. His father came from a modest family and with little formal education became a prominent banker and philanthropist in Ningbo. The youngest of three children, John C. H. Wu began his Chinese education at the age of six. In April 1916, while attending a Western-style secondary school, he married. In 1920 he graduated at the top of his law class at Soochow University’s Comparative Law School.

After further study in the US and Europe, Dr. Wu accepted a research scholarship at Harvard Law School. On his return to China in 1924, he became a professor of Law at his alma mater in Shanghai, and within three years he was appointed Principal of the School of Law. Upon entering private practice in 1930, he soon became one of the most sought after lawyers in Shanghai. A chance reading of the autobiography of St. Thérèsa of Lisieux in 1937 sparked John C. H. Wu’s conversion to Roman Catholicism. The Thérèsian message of God’s love, together with unbounded faith in God’s mercy, struck him with the force of a revelation. Wu had found the Methodist brand of Protestantism emotionally cold and had already investigated Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. Later, his translation of the Psalms into Chinese, commissioned by Chiang Kai-shek, was published in 1946 to wide acclaim.

In the spring of 1945 Dr. John C. H. Wu served as advisor to the Chinese delegation to the United Nations Conference on International Organization at San Francisco and later that year Chiang Kaishek named him as the Chinese minister to the Holy See. Wu presented his credentials to Pope Pius XII in February, 1947. During his mission to the Vatican, Wu completed a Chinese translation of the New Testament, rendered in the classical Chinese style (published in Hong Kong in 1949). In 1949, he moved to the US and held posts at both the University of Hawaii and Seton Hall University.

John C. H. Wu authored and translated numerous books and articles on many subjects including Religion, Philosophy, and Law. His works included translations of the Psalms and New Testament into Chinese, The Interior Carmel, Tao Te Ching of Lao-tzu, The Golden Age of Zen, and the autobiographical Beyond East and West.

Tao Teh Ching by Lao Tzu

Translated by John C. H. Wu

New York: St. John's University Press, 1961

The Golden Age of Zen

by John C. H. Wu

Introduction by Thomas Merton: A Christian Looks at Zen (PDF)

Taipei : The National War College in co-operation with The Committee on the Compilation of the Chinese Library, 1967, 332 p.

“The Golden Age of Zen: The Zen Masters of the T'ang Dynasty”

by John C.H. Wu,

Introduction by Thomas Merton

Foreword by Kenneth Kraft

World Wisdom, Inc., 2003

http://books.google.hu/books/p/7042462899044750?vid=ISBN0-941532-44-5&redir_esc=y

Chapter XIV

Epilogue: Little Sparks of ZenIn this chapter, I have drawn mainly from sources which lie beyond the scope of the present book. But it is hoped that these little sparks will shed some light upon the previous chapters.

1. Time and Eternity

One of the most frequently reiterated couplets in Chinese Zen literature is:

An eternity of endless space:

A day of wind and moon.This brings us, as it were, to the dawn of creation. And nothing stirs the heart and mind of man more profoundly than to be reminded of the first quivering of time in the womb of eternity. An infinite Void, utterly silent and still. In a split second there came life and motion, form and color. No one knows how it happened. It is a mystery of mysteries. But the mere recognition that mystery exists is enough to send any man of sensitive mind into an ecstasy of joy and wonder.

Herein is the secret of the perennial charm of Basho’s haiku:

An old pond.

A frog jumps in,—

Plop!The old pond corresponds to “An eternity of endless space,” while the frog jumping in and causing the water to utter a sound is equivalent to “A day of wind and moon.”

Can there be a more beautiful and soul-shaking experience than to catch ageless silence breaking for the first time into song? Moreover, every day is the dawn of creation, for every day is unique and comes for the first time and the last. God is not the God of the dead, but of the living.

2. A Day of Wind and Moon

Shan-neng, a Zen master of the Southern Sung, gave a meaningful comment on the couplet:

An eternity of endless space:

A day of wind and moon.“Of course,” he said, “we must not cling to the wind and moon of a day and ignore the eternal Void. Neither should we cling to the eternal Void and give no attention to the wind and moon of the day. Furthermore, what kind of a day is it? Other people complain of its extreme heat. But I love the summer day, because it lasts so long. Warm wind comes from the South, and a comfortable coolness is born around the temple and the terrace.”

3. Auspicious Sign

A monk asked the master Ch’u-hui Chen-chi as he appeared for the first time as an Abbot, “I hear that when Shakyamuni began his public life, golden lotus sprang from the earth. Today, at the inauguration of Your Reverence, what auspicious sign may we expect?” The new Abbot said, “I have just swept away the snow before the gate.”

4. The Fun of Being Laughed At

Po-yün Shou-tuan was studying under Yang-ch’i. He was a most earnest student but had little sense of humor. Once Yangch’i asked him under whom he had studied before. Shou-tuan replied, “master Yueh of Ch’a-ling.” Yang-ch’i said, “I hear that he came to his enlightenment when he slipped and fell in crossing a bridge, and that he hit off a very wonderful gatha on the occasion. Do you remember the wording?” Shou-tuan recited:

There is a bright pearl within me,

Buried for a long time under dust.

Today, the dust is gone and the light radiates,

Shining through all the mountains and rivers.On hearing this, Yang-ch’i ran away laughing. Put out by the master’s strange reaction, Shou-tuan could not sleep for a whole night. Early in the morning he went to the master and asked him what was it in his former teacher’s gatha that had caused him to laugh. The master said, “Did you see yesterday the funny antics of the exorcists?” “Yes,” Shou-tuan replied. “In one respect you rather fall short of them,” said the master. Disconcerted once more, Shou-tuan asked, “What do you mean?” The master said, “They love to see others laugh, but you are afraid to see others laugh!” Shou-tuan was enlightened. Only then did he realize what Aelred Graham calls the “importance of being not earnest.”

5. The Open Secret

Huang-lung Tsu-hsin was on intimate terms with the famous man of letters Huang Shan-ku (1045-1105). One day, Shan-ku besought Huang-lung to give him a secret shortcut to Zen. Huang-lung said, “It is just as Confucius put it, ‘My dear pupils, do you really think that I am hiding anything from you? In fact, I have hid nothing from you.’ What have you thought of these words?” As Shan-ku fumbled for an answer, Huang-lung interjected, “Not this, not this!” Shan-ku felt greatly frustrated. One day, as Shan-ku accompanied Huang-lung in strolling on the mountain, the cinnamon trees were in full bloom in the valleys. Huang-lung asked, “Do you perceive the fragrance of the cinnamon?” “Yes, I do,” replied Shan-ku. Huang-lung said, “You see, I have hid nothing from you!” Shan-ku was enlightened, and did obeisance, saying, “What a grandmotherly heart Your Reverence has got!” Huang-lung smiled and said, “It is my only wish to see you arrive home.”

6. Cutting the Gordian Knot

The masters of Zen often resort to the trick of putting their students in a dilemma from which there is apparently no outlet. When T’ien-i was studying under Ming-chüeh of Ts’ui-feng, the latter made an enigmatic statement: “Not this, not that, not this and that altogether!” That set T’ien-i a-wandering. As T’ien-i was reflecting on this, Ming-chüeh drove him out by beating. This happened several times. Later, T’ien-i was put in charge of carrying water. Once the pole on his shoulder suddenly split so that the pails fell to the ground pouring out all the water. At that very moment he was awakened to his self-nature and found himself out of the dilemma.

Hsiang-yen Chih-hsien once posed a similar question to his community: “The whole affair is like a man who hangs on to a tall tree by his teeth, with his hands grasping no branch and his feet resting on no limb. A man under the tree suddenly asks him, ‘What is the significance of Bodhidharma coming from the West?’ If he does not answer, he fails to respond to the question. But if he answers, he falls and loses his life. Now what must he do?”

At that time, the Elder Chao of Hu-t’ou happened to be in the assembly. He stood forth, saying, “Let us not ask about the man who is already on the tree. Can you tell me something about him before he has climbed up the tree?” Hsiang-yen burst into a loud laughter.

I-tuan, one of Nan-ch’üan’s great disciples, said to his assembly, “Speech is blasphemy, silence a lie. Above speech and silence there is a way out.”

Fa-yün of the House of Yün-men said to his assembly, “If you advance one step, you lose sight of the principle. If you retreat one step, you fail to keep abreast of things. If you neither advance nor retreat, you would be as insensible as a stone.” A monk asked, “How can we avoid being insensible?” “Veer and do the best you can,” replied the master. The monk: “How can we avoid losing sight of the principle and at the same time keep abreast of things?” The master: “Advance one step and at the same time retreat one step.”

7. The Way Upward

Zen masters are soaring spirits. However high a state they have attained, they never cease to speak of the way upward. But it is interesting to note that at a certain point, the only way to go upward is by descending to the earth. Thus, when a monk asked the master Chi-ch’en, “What is the way upward?” the latter replied, “you will hit it by descending lower.”

This makes me think of St. John of the Cross, who wrote:

By stooping so low, so low,

I mounted so high, so high,

That I was able to reach my goal.Despite all the differences of undertones and overtones between the two, yet it is intriguing to note the identity of the paradoxical form in which their insights were presented.

St. John of the Cross is a master of paradoxes. For instance, this:

In order to arrive at having pleasure in everything, Desire to have pleasure in nothing.

In order to arrive at possessing everything, Desire to possess nothing.

In order to arrive at being everything, Desire to be nothing.

In order to arrive at knowing everything, Desire to know nothing.All these paradoxes have their counterparts in the philosophy of Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu. As Chuang Tzu puts it, “Perfect joy is to be without joy.” Lao Tzu says:

The Sage does not take to hoarding.

The more he lives for others, the fuller is his life.

The more he gives the more he abounds.Again:

Is it not because he is selfless

That his Self is realized?Finally, according to Lao Tzu, to know that we do not know is the acme of knowledge.

8. The Dumb Person

A Chinese proverb says, “When a dumb person eats huan- glien (a bitter herb used for medicine), he feels the bitterness but has no one to tell it to.” The Zen masters have a knack of touching up a popular saying for their own purposes. Yang-ch’i, for example, said, “When the dumb person has got a dream, to whom can he tell it?” Hui-lin Tz’u-shou was even more ingenious, as you will see from the following dialogue:

Monk: "When a man realizes that there is but does not know how to express it, what is he like?"

Tz'u-shou: "He is like a dumb person eating honey!"

Monk: "When a man, who actually does not realize that there is, yet talks glibly about it, what would he be like?"

Tz'u-shou: "He is like a parrot calling people's names!"

9. How Tao-Shu Coped With a Monster

Tao-shu, a disciple of Shen-hsiu, was living on a mountain with a few pupils. There frequently appeared to him a strange man, simple in clothes but wild and boastful in speech. He could take on the appearance of a Buddha, a Bodhisattva or an Arhat or whatever he had a fancy to. Tao-shu’s pupils were all amazed; they could not make out who that wizard was and what he was after. For ten years his apparitions continued. But one day he vanished away, never to return.

Tao-shu said to his pupils, “The wizard is capable of all kinds of tricks in order to bedevil the minds of men. My own way of coping with them is by refraining from seeing and hearing them. His tricks, however multifarious, must come to an end some day, but there is no end to my non-seeing and non-hearing!”

As another master has put it, “What is inexpressible is inexhaustible in its use.”

10. A Motley Bodhisattva

The Bodhisattva Shan-hui, better known as Fu Ta-shih, born in 497, was one of the most extraordinary figures in Buddhism and an important precursor of the School of Zen. Once he was invited by Emperor Wu of Liang (who reigned from 502 to 549) to give a lecture on the Diamond Sutra. No sooner had he ascended to the platform than he rapped the table with his rod and descended. The poor emperor was simply lost in amazement. Yet Shan-hui asked, “Does Your Majesty understand?” “I don’t understand at all,” replied the emperor. “But the Ta-shih has already finished his sermon!” Shan-hui remarked.

On another occasion, as Shan-hui was delivering a sermon, the emperor arrived, and the whole community rose to show their respect. Only Shan-hui remained seated without any motion. Somebody took him to task, saying, “Why don’t you stand up when His Majesty has come?” Shan-hui said, “If the realm of the Dharma is unsettled, the whole world would lose its peace.”

One day, wearing a Buddhist cassock, a Taoist cap, and Confucian shoes, Shan-hui came into the court. The emperor, amused by the motley attire, asked, “Are you a Buddhist monk?” Shan-hui pointed at his cap. “Are you then a Taoist priest?” Shan-hui pointed to his shoes. “So, you are a man of the world?” Shan-hui pointed to his cassock.

Shan-hui is said to have improvised a couplet on the occasion:

With a Taoist cap, a Buddhist cassock, and a pair of Confucian shoes,

I have harmonized three houses into one big family!If, as Suzuki so well says, Zen is the “synthesis of Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism applied to our daily life as we live it,” the tendency was already prefigured in Fu Ta-shih.

Two gathas from Fu Ta-shih have been frequently quoted by Zen masters. One reads:

Empty-handed, I hold a hoe.

Walking on foot, I ride a buffalo.

Passing over a bridge, I see

The bridge flow, but not the water.The other reads:

Something there is, prior to heaven and earth,

Without form, without sound, all alone by itself.

It has the power to control all the changing things;

Yet it changes not in the course of the four seasons.

11. “I Have Lost Myself”

When Chuang Tzu wrote “Wu Shang ngo” (“I have lost myself”), he meant that his real self had got rid of his individual ego. Self-realization through self-loss is the universal message of all religion and wisdom. Lose and you will gain. Be blind and you will see; be deaf and you will hear. Leave home and you will find home. In one word, die and you will live. Life is a perpetual dialogue between wu and ngo.

12. Leaving Home for Home

Buddhist monks call themselves proudly “home-leavers.” It is indeed not a small thing to leave your dear ones at home and wander forth all alone in search of Tao. Once a great prince told the Zen master Tao-ch’in of Ching-shan that he was thinking of being a home-leaver. “What?” said the master, “It takes a fullgrown man to leave home. This is not something that the generals and prime ministers can undertake!”

Yet many Zen masters have spoken of enlightenment in terms of return home. I don’t know how many times they have referred to Tao Ch’ien’s “Song of Returning Home.” The following poem by the Zen master Ying-yüuan is typical:

The cold season is coming to an end

And Spring is arriving!

Untethered buffaloes and oxen are

Jumping all around.* * *

The shepherds have cast away their whips.

Too lazy to blow their holeless flute,

They clap their hands and laugh boisterously.

“Homeward, Homeward, Homeward Ho!”

They sing as they go.

Entering the thickets veiled with mists and vapors

They lie down with their clothes on.

13. Playing God or Letting God Play?

One of the most significant books of this age of confusion is Dom Aelred Graham’s Zen Catholicism: A Suggestion. As Dom Aelred sees it, the spirit of Zen lies in letting God play rather than playing God. He shows a profound insight when he says that Satori or enlightenment “is the disappearance of the selfconscious me before the full realization of the unselfconscious I.” It is only after this realization that one no longer plays God, but lets God play.

This state is ineffable, but we find a suggestive picture of it in a beautiful passage from The Way of Chuang Tzu in the beautiful version of Thomas Merton:

Fishes are born in water,

Man is born in Tao.

If fishes, born in water,

Seek the deep shadow

Of pond and pool,

All their needs

Are satisfied.

If man, born in Tao,

Sinks into the deep shadow

Of non-action

To forget aggression and concern,

He lacks nothing

His life is secure.

Moral: “All the fish needs

Is to get lost in water.

All man needs is to get lost

In Tao.”

14. A Taste of Suzuki’s Zen

It was in the summer of 1959, in Honolulu. The University of Hawaii was holding its 3rd East-West Philosophers’ Conference. Among its panel members was Dr. Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, who was then already eighty-nine. One evening, as he was reporting to us the Japanese philosophy of life, I heard him say, “The Japanese live by Confucianism, but die by Buddhism.” I was struck by this remarkable statement. Of course, I understood what he meant, for this is more or less true also of the Chinese. All the same, I thought that it was an exaggeration, which stood in need of some amendment. So, as soon as he had finished his report, I asked the Chairman to permit me to put a question to Dr. Suzuki. Having got the green light, I proceeded, “I was very much struck by Dr. Suzuki’s observation that Japanese live by Confucianism but die by Buddhism. Now, a few years ago, I had the pleasure of reading Dr. Suzuki’s Living By Zen. Is Zen not a school of Buddhism? or can it be that Dr. Suzuki is the only Japanese who lives by Zen? If there are other Japanese living by Zen, then the statement that Japanese live by Confucianism and die by Buddhism would seem to need some revision.” The Chairman very carefully relayed my question to Dr. Suzuki (because he was somewhat hard of hearing), and the whole panel was agog for his answer. But no sooner had the Chairman presented the question than Dr. Suzuki responded with the spontaneity of a true Zen master, “Living is dying!” This set the whole conference table aroar. Everybody was laughing, apparently at my expense. I alone was enlightened. He did not answer the question, but he lifted the questioner to a higher plane, a plane beyond logic and reasoning, beyond living and dying. I felt like giving Dr. Suzuki a slap in order to assure him that his utterance had clicked. But after all, must I not still live by Confucianism?

15. An Encounter with Holmes’ Zen

In 1923 I spent my Christmas holidays with my old friend Justice Holmes in Washington. One morning, he was showing me around his wonderful private library, which was full of books on art, literature and philosophy, besides works on law. From time to time he pulled out a book from the shelves and told me what he thought of it. He told me how William James and Josiah Royce used to play hide-and-seek with God; how he had enjoyed the Golden Bough; how deeply he was impressed by the works of de Tocqueville, especially his Ancien Régime, which he said that I must read in order to keep my idealism from going wild; and so on and so forth. Finally, assuming a very serious tone, he said to me, “But my dear boy, I have not yet shown you the best books in the library.” “Where do you keep them?” I asked impatiently. He pointed me to some far corner of the room, saying, “There!” When I looked, I found to my greatest amazement an empty shelf! I laughed, saying, “How characteristic of you, Justice! Always looking forward!” Later, it occurred to me that Holmes was not merely looking forward but upward. It was only after I had studied the Tao Teh Ching, with its stress on the empty and invisible, that I realized the full purport of Holmes’ pointing.

But somehow Holmes’ jolly action liberated my mind from the world of conventional inhibitions. One evening, as we were, to use his graphic expression, “twisting the tail of the cosmos” together, Mrs. Holmes (who, like Holmes, was in her early eighties and as vivacious as he) came in. As soon as I saw her, I rose to greet her and, in a jeu d’esprit, said to her, “Madame, may I present to you my friend Justice Holmes?” She shook hands with him, saying, “It’s a pleasure to know you, Mr. Oliver Wendell Holmes!” Probably that was what she had said more than sixty years ago at their first meeting! At that moment, the three of us looked at one another with an understanding smile. Had William James not said that a philosopher looks at familiar things as if they were strange, and strange things as if they were familiar? At that time I had only had a smattering of Taoism, but never had heard of Zen. As I look at it now, it was undoubtedly a genuine case of Zen. There was a sudden meeting of eternity and time. Like those wild geese flying over the heads of Ma-tsu and Pai-chang, this experience has passed but is not gone.

16. The Metaphysical Background of Zen

Zen is not without a metaphysical basis, although for the most part it remains inarticulate. The essentials of its metaphysics are to be found in the first chapter of the Tao Teh Ching:

If Tao can be translated into words, it would not be Tao as such.

Any name that can be given it is not its eternal name.

It is nameless, because it is prior to the universe:

Yet it is nameable in the sense that it is “Mother of all things.”

In essence, it is a formless void:

In manifestation, it has all shapes and forms.

But both the essence and manifestation are one and the same origin,

Although they are differently named.

This is what is called Mysterious Identity.

In the depth of this Mystery

Is the door to all ineffable truths.The Zennist interpretation of the above can be briefly stated. In the first place, Tao being something fundamentally inexpressible, any talk about it is more or less a tour de force. It cannot be communicated to another. Every one of us must find it in himself by direct intuition. The words of the masters are meant only to provoke the working of this intuition in you; not to infuse it into you. All the names they may call it are only expedient means for awakening you to the Tao in you. Secondly, Tao is beyond names and namelessness. Absolutely, in its suchness, it cannot be named: but relatively to the world of things, it is, as it were, their common Mother. Thirdly, it embraces both the noumenal and the phenomenal, which represent but two aspects of Tao, which is their common Origin or Source. It embraces both, because it transcends both. This unity of transcendence and immanence is the mystery of mysteries. Fourthly, being the mystery of mysteries, it would be utterly vain to try to understand it. Yet we ourselves are mysteries, mysterious members of the mysterious Whole. Although we cannot understand it, yet we can embrace it. In fact, we live, move, and have our being in it. We can dive into it until we arrive at the door of all wonders. As Merton had discovered long before he had looked into Taoism or Zen, “A door opens in the center of our being and we seem to fall through it into immense depths which, although they are infinite, are all accessible to us; all eternity seems to have become ours in this one placid and breathless contact.”7

17. Riding an Ass

According to Ch’ing-yüan, also called Fo-yen, there are two diseases in connection with the practice of Zen. “The first is to ride an ass in search of the ass. The second is to ride the ass and refuse to dismount.” It is easy to see the silliness of seeking the ass you are riding. As your attention is turned outwards, you will never look inside, and all your search will be so much ado about nothing. The kingdom of God is within you, but you seek it outside. There is no telling how many troubles in the world have had their origin just in this wrong orientation.

As Ma-tsu has said, “You are the treasure of your own house.” To seek it outside is a pathetic endeavor, because you will always be disappointed. For, at the bottom of your heart, you are seeking the real treasure. Although you may be satisfied for a few moments with faked substitutes, in the depths of your subconsciousness, you can never deceive yourself. Léon Bloy has uttered a profound insight when he said, “There is but one sorrow, and that is to have lost the Garden of Delights, and there is but one hope and one desire, to recover it. The poet seeks it in his own way, and the filthiest profligate seeks it in his. It is the only goal.” But the tragedy is that, not realizing that the Garden of Delights is within us, we seek it by flying away from it with an ever-increasing speed.

The second disease is even more subtle and difficult to cure. This time, you are no longer seeking outside. You know that you are riding your own ass. You have already tasted an interior peace infinitely sweeter than any pleasures you can get from the external things. But the great danger is that you become so attached to it that you are bound to lose it altogether. This is what Ch’ing-yüan meant by “riding the ass and refusing to dismount.” This disease is common to contemplative souls in all religions. In his Seeds of Contemplation, Thomas Merton has uttered a salutary warning against precisely the same pitfall:

Within the simplicity of this armed and walled and undivided interior peace is an infinite unction which, as soon as it is grasped, loses its savor. You must not try to reach out and possess it altogether. You must not touch it, or try to seize it. You must not try to make it sweeter or try to keep it from wasting away …

The situation of the soul in contemplation is something like the situation of Adam and Eve in Paradise. Everything is yours, but on one infinitely important condition: that it is all given.

There is nothing that you can claim, nothing that you can demand, nothing that you can take. And as soon as you try to fake something as if it were your own—you lose your Eden.

In this light, you can appreciate the profound insight of Lung-t’an that the priceless pearl can only be kept by one who does not fondle it.

Ch’ing-yüan’s final counsel is, “Do not ride at all. For you yourself are the ass, and the whole world is the ass. You have no way to ride it… If you don’t ride at all the whole universe will be your playground.”

18. The Importance of Hiddenness

Nan-ch’üan once went to visit a village and found to his surprise that the village head had already made preparations to welcome him. The master said, “It has been my custom never to let anyone know beforehand my goings about. How could you know that I was coming to your village today?” The village head replied, “Last night, in a dream the god of the soil shrine reported to me that Your Reverence would come to visit today.” The master said, “This shows how weak and shallow my spiritual life is, so that it can still be espied by the spiritual beings!”

The Zen masters set little or no value on the siddhis or magical powers. This point is well illustrated in the life of Niu-t’ou Fa-yung (594-657). Niu-t’ou came from a scholarly family in the city of Yen-ling in modern Kiangsu. By the time he was nineteen, he was already well steeped in the Confucian classics and the dynastic histories. Soon after he delved into Buddhist literature, especially the Prajna scriptures, and came to an understanding of the nature of Shunyata. One day he said to himself, “Confucianism sets up the norms for mundane life, but after all they do not represent the ultimate Law. The contemplative wisdom of the Prajna is truly the raft to ford us over to the supramundane.” Thereupon he retired into a hill, studied under a Buddhist master, and had his head shaved. Later he went to the Niu-t’ou Mountain and lived all alone in a cave in the neighborhood of the Yu-hsi Temple. A legend has it that while he was living there, all kinds of birds used to flock to his hermitage, each holding a flower in its beak, as if to pay their homage to the holy man.

Some time during the reign of Chen-kuan (627-650), Taohsin, the Fourth Patriarch of the Chinese School of Zen, looking at the Niu-t’ou Mountain from afar, was struck by its ethereal aura, indicating that there must be some extraordinary man living there. So he took it upon himself to come to look for the man. When he arrived at the temple, he asked a monk. “Is there a man of Tao around here?” The monk replied, “Who among the home-leavers are not men of Tao?” Tao-hsin said, “But which of you is the man of Tao, after all?” Another monk said, “About three miles from here, there is a man whom people call the ‘Lazy Yung,’ because he never stands up when he sees anybody, nor gives any greeting. Can he be the man of Tao you are looking for?” Tao-hsin then went deeper into the mountain, and found Niu-t’ou sitting quietly and paying no attention to him. Tao-hsin approached him, asking, “What are you doing here?” “Contemplating the mind,” said Niu-t’ou. “But who is contemplating, and what is the mind contemplated?” Tao-hsin asked. Stunned by the question, Niu-t’ou rose from his seat and greeted him courteously, saying, “Where does Your Reverence live?” “My humble self has no definite place to rest in, roving east and west.” “Do you happen to know the Zen master Tao-hsin?” “Why do you ask about him?” “I have looked up to him for long, hoping to pay my homage to him some day.” “This humble monk is none other than Tao-hsin.” “What has moved you to condescend to come to this place?” “For no other purpose than to visit you!” Niu-t’ou then led the Patriarch to his little hermitage. On seeing that it was all surrounded by tigers and wolves, Tao-hsin raised his hands as if he were frightened. Niu-t’ou said, “Have no fear! There is still this one here!” “What is this one?” Tao-hsin asked. Niu-t’ou remained silent. Some moments later, Tao-hsin scribed the word “Buddha” on the rock on which Niut’ou used to sit. Gazing at the word, Niu-t’ou showed a reverential awe. “Have no fear,” said Tao-hsin, “there is still this one here.” Niut’ou was baffled. Bowing to the Patriarch, he begged him to expound to him the essential Truth. Tao-hsin said, “There are hundreds and thousands of Dharmas and yogas; but all of them have their home in the heart. The supernatural powers and virtues are as innumerable as the sand on the beaches; but all without exception spring from the mind as their common fountainhead. All the paths and doors of shila, dhyana and Prajna, all the infinitely resourceful siddhis, are in their integral entirety complete in your mind and inseparable from it. All kleshas and karmic hindrances are fundamentally void and still. All operations of cause and effect are like dreams and illusion. Actually there are no three realms to escape from. Nor is there any Bodhi or enlightenment to seek after. All beings, human and nonhuman, belong to one universal, undifferentiated Nature. Great Tao is perfectly empty and free of all barriers; it defies all thought and meditation. This Dharma of Suchness you have now attained. You are no longer lacking in anything. This is Buddhahood. There is no other Dharma besides it. All that you need is to let the mind function and rest in its perfect spontaneity. Do not set it upon contemplation or action, nor try to purify it. Without craving, without anger, without sorrow or care, let the mind move in untrammeled freedom, going where it pleases. No deliberate doing of the good, nor deliberate avoiding of the evil. Whether you are traveling or staying at home, sitting up or lying down, in all circumstances you will see the proper occasion for exercising the wonderful functions of a Buddha. Then you will always be joyful, with nothing to worry about. This is to be a Buddha indeed!”

Niu-t’ou was enlightened. Thereafter he emerged from his life as a hermit, and gave himself to the active works of charity and to the expounding of the Mahaprajnaparamita Sutra.

Although the “Zen of Niu-t’ou” has been regarded by later Chinese masters as outside of the main currents of the School of Zen, his contributions to the elucidation of the philosophy of Nagarjuna are not to be minimized. His main teaching that illumination is to be achieved through contemplation of the Void spread to Japan through Dengyo Daishi (767-822). In China, the “Zen of Niu-t’ou” claimed adherents as late as in the eighth generation after him. Even at present, Niu-t’ou’s gathas are cherished by Buddhists of all schools as an integral part of the Mahayana philosophy in China.

Even in the School of Zen, one of the most popular koans has to do with Niu-t’ou. The question is: “How was it that before Niu-t’ou had met the Fourth Patriarch, the birds used to flock to him with flowers in their beaks, while after his enlightenment the prodigy ceased?” Of course, all the masters of Zen have of one accord regarded the latter state as incomparably higher than the former state. But everyone has his own way of describing the two states. Shan-ching described the earlier state as “a magical pine-tree growing in a wonderland, admired by all who see it,” while he likened the latter state to a tree with “its leaves fallen and its twigs withered, so that the wind passes through it without leaving any music.” But the most graphic comment was from the master I of Kuang-te. Of the first state he remarked:

When a jar of salted fish is newly opened,

The flies swarm to it buzzing all around.Of the second, he stated:

When the jar is emptied to the bottom and washed clean,

It is left all alone in its cold desolation.Huai-yüeh of Chang-chou spoke of the first state as “myriad miles of clear sky with a single speck of cloud”; and of the second as “complete emptiness.” To Ch’ung-ao of Lo-feng, in the first state “solid virtue draws homage from the ghosts and spirits”; while in the second state, “the whole being is spiritualized, and there is no way of gauging it.”

From the above samplings, one can see clearly the authenticity of the spirituality of Zen. With the sureness of their experiential insight, the Zen masters seem to have hit upon an unerring scale of values in spiritual life. Sensible consolations are not to be despised, but all the same they must be outgrown if one is to advance higher. Desolation is like the unleavened bread which may not taste so sweet but is of vital essence to one’s life. There is still another point which is noteworthy. One’s internal life must, of course, be hidden from the human eye. This was true of Niu-t’ou even before he had met Tao-hsin, as he was already a hermit. But, as Nan-ch’üan so clearly saw, your internal life must be so hidden that even the demons and angels have no way of espying it.

But in the eye of Tao, what appears to be desolation is in reality a garden of flowers. This point has been beautifully articulated by two masters of the House of Yün-men. One was Yüanming of Te-shan, whose comment on the first state was:

When autumn comes, yellow leaves fall.

And his comment on the second state was:

When Spring comes, the grasses spontaneously grow green.

The other was Fa-chin of Yün-men, who spoke of the first state as “fragrant breeze blowing the flowers to fading,” and of the second as “showering anew upon fresher and more beautiful flowers.”

This indeed is a glorious vision. These masters actually see the desolate land flourishing like the lily!

Any student of comparative mysticism will see in the tradition and spirit of Zen the hallmark of authenticity. It is little wonder that Father Thomas Berry, a profound student of Oriental philosophy and religion, should have called Zen “the summit of Asian spirituality.” He certainly knows what he is talking about.

19. Who Has Created God?

Once some Buddhist asked me, “God has created everything, but who could have created God?” I said, “That’s exactly what I want to know: who could have created God?” And we had a good laugh together.

This question is similar to what Chao-chou asked of Ta-tz’u, “What can be the substance of Prajna?” When Tatz’u asked back, “What can be the substance of Prajna?” Chao-chou realized immediately the silliness of his question and burst out laughing.

20. The Romance of Self-Discovery

“For me to be a saint means to be myself. Therefore the problem of sanctity and salvation is in fact the problem of finding out who I am and of discovering my true self.”8 This is what Thomas Merton wrote almost twenty years ago, when he had hardly peeped into the works of Chuang Tzu or any of the Zen masters. Yet this practically sums up the whole endeavor of Zen and the Taoists. It is therefore not by chance that he should in recent years have taken such a genuine interest in Taoism and Zen.

To Chuang Tzu, “Only the true man can have true knowledge.” Instead of starting from “Cogito, ergo sum,” his starting point was “Sum, ergo cogito”! Be a true man, and you will have true knowledge. The true man is one who has discovered his true self. Our whole life is a romance, the romance of discovering our true self. Even the fundamental moral precepts such as: Avoid all evil, pursue all good, and purify your mind, are but preliminaries to the finding and being of oneself. Chuang Tzu has summed up this supreme romance of life in a beautiful passage:

The moral virtues of humanity and justice are only the wayside inns that the sage-kings of old have set up for the wayfarers to lodge for a night. They are not for you to occupy permanently. If you are found to tarry too long, you will be made to pay heavily for it. The perfect men of old borrowed their way through humanity and lodged in justice for a night, on their way to roam in the transcendental regions, picknicking on the field of simplicity, and finally settling in their home garden, not rented from another. Transcendency is perfect freedom. Simplicity makes for perfect health and vigor. Your garden not being rented from another, you are not liable to be ejected. The ancients called this the romance of hunting for the Real.

Our whole life is, then, a pilgrimage from the unreal to the Real. No romance can be more meaningful and thrilling than this. Because the goal and the process are romantic, there is nothing in life which is not romantic. That’s why the Zen masters have so often quoted a significant line from a love poem

In her hands, even the prose of life becomes poetry.

Many years ago, Justice Holmes wrote me that I must “face the disagreeable” and learn “to tackle the unromantic in life with resolution to make it romantic.” The world will not fully realize how this true man of America led me back to the wisdom of the East, or, shall I say, to my aboriginal Self.

21. The Spirit of Independence

One of the most striking qualities of the Zen masters is their spirit of independence. Single-heartedly devoted to the one thing necessary, they refuse to bow to anything or anyone short of that. As Shih-t’ou declared, “I would rather sink to the bottom of the sea for endless eons than seek liberation through all the saints of the universe!” This is no sign of pride, but rather the part of wisdom. The fact is that no external factor can ever give you freedom. Truth alone makes you free, and you must realize Truth by yourself.

There is an interesting anecdote about Wen-hsi, disciple of Yang-shan. It is said that when Wen-hsi was serving in the kitchen, Wen-ju (Manjushri) often appeared to him. Wen-hsi took up a cooking utensil and drove away the apparition, saying, “Wen-ju is Wen-ju, but Wen-hsi is Wen-hsi!”

In the same spirit, Ts’ui-yen declared:

The full-grown man aspires to pierce through the heavens:

Let him not walk in the footsteps of the Buddha!The Zen masters realize what a superlatively hard task it is to be a full-grown man, what heart-rending trials and backbreaking hardships, what gravelike loneliness, what strangling doubts, what agonizing temptations one must go through before one can hope to arrive at the threshold of enlightenment. That’s why they have approached it with all their might, and have never been willing to stop short of their ultimate goal.

22. The Function of a Master

The Zennists are so independent that they have often declared that they have got nothing from their masters. As Hsüeh-feng said in regard to his master Te-shan, “Empty-handed I went to him, and empty-handed I returned.” Strictly speaking, this is true. No master would claim to have instilled anything into his disciple. Still, the master does have a necessary function to perform.

When Shih-t’ou visited his master Ch’ing-yüan for the first time, the master asked, “Where do you come from?” Shih-t’ou answered that he was from Ts’ao-ch’i, where the late Sixth Patriarch had been teaching. Then Ch’ing-yüan asked, “What have you brought with you?” Shih-t’ou replied, “That which had never been lost even before I went to Ts’ao-ch’i.” Ch’ing-yüan further asked, “If that is the case, why did you go to Ts’ao-ch’i at all?” Shih-t’ou said, “If I had not gone to Ts’ao-ch’i, how could I realize that it had never been lost?”

From this it is crystal-clear that although a master cannot actually instill anything into you, he can nevertheless help open your eyes to what you have within you. His instruction may at least serve as a catalyst in your enlightenment.

23. Poems Used by Zen Masters

The most favorite lines among the Zen masters are Wang Wei’s:

I stroll along the stream up to where it ends.

I sit down watching the clouds as they begin to rise.I have seen this charming couplet many times in Zen literature. One master made it his own by adding two words to each line:

Without strolling along the stream up to where it ends,

How can you sit down watching the clouds as they begin to rise?Wang Chih-huan’s famous couplet has also been quoted to evoke the way upward:

To see farther into the horizons,

Let’s mount one more flight of stairs.But the most interesting instance is Wu-tsu Fa-yen’s use of a couplet from a popular love song:

Time and again she calls for “Little Jade,”

Not that she needs her service.She only wants her sweet bridegroom

To recognize her voice.This needs a little explanation. “Little Jade” was the name of the bride’s maid. In old China, when the girl of a well-to-do family was married, she was usually accompanied for the first few days by a handmaid to help her in dressing and undressing. In normal cases, the bridegroom and the bride had never met before their wedding, but usually they fell in love with each other at the first sight. In this case, at any rate, she was already in love with her bridegroom, but like other brides she was still too shy to speak directly with the bridegroom, who was perhaps just as shy. To familiarize him with her voice, she called her maid as though she needed her service. When her maid came and asked her if she needed anything, she would reply, “Oh thanks, nothing important!”

But what has all this to do with Zen? The bridegroom stands for “The True Man of No Title,” the Inexpressible and Inconceivable. You cannot call him, because he has no name. On the other hand, although he has no name and you cannot speak about him, there is no denying that you are in love with him with your whole mind, your whole heart, your whole being. So, even your calling the names of others is nothing but an expression of your love for him. He is the meaning of all your action and speech, which far from distracting you from him, only help you to vent your feeling of love.

Fa-yen’s disciple, Yüan-wu, wrote a gatha in the form of an excellent love poem:

The incense in the golden duck is burning out,—

She is still waiting behind the embroidered curtains.

In the midst of flute-playing and songs,

He returns intoxicated, supported by friends.

The happy adventure of the romantic youth,—

His lady alone knows its sweetness.Zen is so personal a thing that it has often been compared to eating and drinking. This gatha from Yüan-wu is a lone instance of speaking of Zen in terms of sexual love. But his meaning is clear. He has elsewhere given another beautiful description of Satori in terms of landscape: “You gain an illuminating insight into the very nature of things, which now appear to you as so many fairy flowers having no graspable realities. Here is manifested the unsophisticated Self which is the original face of your being; here is shown all bare the most beautiful landscape of your birthplace.”

24. Chuang Tzu and the Dharma Eye

Liang-shan Yüan-kuan, a member of the House of Ts’aot’ung, was once asked by a monk to tell him what is the right Dharma Eye. He answered, “It is in the Nan Hua!” Now, Nan Hua was the canonical title which had been conferred on the first chapter of The Book of Chuang Tzu in 742. This answer must have surprised the monk. So he asked, “Why in the Nan Hua?” The master replied, “Because you are asking about the right Dharma-Eye!”

As time went on, the fundamental affinity between Chuang Tzu and Zen became more and more widely recognized. A number of Zen masters brought their profound insights into the nature of the Absolute to bear upon Chuang Tzu’s philosophy of Tao. For instance, the outstanding Zen master of the Ming period, Han-shan Te-ch’ing (1546-1623) wrote an annotation of the first book of Chuang Tzu, which seems to me far more illuminating than Kuo Hsiang’s annotation.

Ta-hui Tsung-kao (1089-1163) gave an excellent exposition of Chuang Tzu’s idea that Tao is not only beyond speech but beyond silence as well. He made an effective use of this idea in opposing the advocates of what is called “silent contemplation Zen.” He was equally opposed to the Hua-t’ou Zen, the theory that Zen consists in tackling with the koan. He went to the extent of burning his master Yüan-wu’s Pi-yen Chi. His notion of Zen corresponds to Chuang Tzu’s notion of Tao: it is everywhere and nowhere. In its practical aspect, Zen consists in doing or non-doing in accordance with the fitness of the occasion. There is silence in speech, speech in silence; there is action in inaction, inaction in action. Timeliness is all. If your action is timely it is as though you had not acted. If your speech is timely, it is as though you had not spoken.

All-rounded as his doctrine is, Ta-hui is more speculative than contemplative. He is like a singer whose voice is highpitched and loud; but one feels that it comes from the throat rather than the diaphragm. With the great masters of T’ang, their voice seems to come from the heels. Ta-hui is too brilliant to be profound. It was not for nothing that the Lin-chi Zen after Ta-hui began to decay, just as the Fa-yen Zen began to fade out after Yen-shou.

25. Goodness as an Entrance to Zen

The Zennists have usually emphasized intuitive perception of Truth as the way to enlightenment. But in my view, not only the sudden perception of Truth, but also an unexpected experience of spontaneous Goodness, can liberate you from the shell of your little ego, and transport you from the stuffy realm of concepts and categories to the Beyond. Whenever Goodness flows unexpectedly from the inner Self, uncontaminated by the ideas of duty and sanction, there is Zen. I need to give but a few examples of such Goodness. (These examples are all taken from a popular book.)

Han Po-yu. His mother was of irascible disposition. When Poyu was a child, he was often beaten by her with a staff. He always received the beating graciously, without crying. One day, however, when he was beaten, he wept piteously. Greatly surprised, his mother said, “On all former occasions you always received my discipline gladly. What makes you cry today?” Po-yu replied, “In the past I always felt pain when Mom beat me, so that I was secretly comforted that Mom was in vigorous health. Today, I no longer feel any pain. So I am afraid that my dear Mom is decaying in energy. How can I help crying?”

Hung Hsiang. His father was down with paralysis. Hsiang attended upon him, day and night, serving medicine and helping him to get up on necessary occasions. His father felt that it was unfair to his daughter-in-law to keep her newly married husband away from her even in the night. So he told his son, “I am getting better now. Please go to sleep in your own room. It will be enough to leave a servant to wait on me at night.” Hsiang pretended to accede to his father’s wishes, but as soon as his father was asleep, he stole into the room and slept beside his bed. In the depth of night, the father was, as usual, under the necessity of getting up. Seeing that the servant was soundly asleep, he attempted to stand on his feet but tottered. Suddenly, Hsiang rose to hold him, keeping him from falling in the nick of time. The father, taken by surprise, asked, “Who are you?” “It’s me, Dad!” said Hsiang. Realizing to what heroic lengths his son had gone in his filial love, he embraced him, weeping for gratitude and saying, “Oh God! What a filial child you have given me!” Hung Hsiang was called by his neighbors “master of Hidden Virtue.”

Yang Fu. He took leave of his parents and went to Szechwan to visit the Bodhisattva Wu Chi. He met an old monk on the way, who asked him, “Where are you going?” Yang Fu told him that he was going to visit Wu Chi and to become his disciple. The old monk said, “It is better to see the Buddha himself than to see a Bodhisattva.” Yang Fu asked where could he find the Buddha. The old monk said, “Just return home, and you will see someone meeting you draped in a blanket and wearing slippers on the wrong feet. Mark you well: this will be the very Buddha.” Yang Fu accordingly turned his way homeward. On the day of his arrival, it was already late in the night. His mother had already gone to bed. But as soon as she heard the knock of her son, she was so excited that she had no time to dress up. Putting on a blanket for an overcoat, and hastily stepping into her slippers right-side-left, she came to the door to welcome him back. On seeing her, Yang Fu was shocked into enlightenment. Thereafter he devoted all his energies to serving his parents, and produced a big volume of annotations on the Classic of Filial Piety.

It is significant that the last story is found in a Taoist compilation of edifying anecdotes. So we have here a Taoist using the wisdom of a Buddhist Bodhisattva (for the old monk was none other than Wu Chi) for the promotion of Confucian ethics.

Even morality can be beautiful when it springs directly from the pure fountain of the child’s heart. It is no less a door to enlightenment than the croak of a frog or the upsetting of a chamber-vessel.

26. Han-shan and Shih-te

One of the most cherished poems of the T’ang dynasty was a quatrain by Chang Chi (from latter part of the 8th century) on “A Night Mooning at Maple Bridge”:

The moon has gone down,

A crow caws through the frost.

A sorrow-ridden sleep under the shadows

Of maple trees and fishermen’s fires.

Suddenly the midnight bell of Cold Mountain Temple

Sends its echoes from beyond the city to a passing boat.This poem is redolent of Zen. It seems as though eternity had suddenly invaded the realm of time.

The Cold Mountain Temple in the suburbs of Soochow was built in memory of Han-shan Tzu or the “Sage of Cold Mountain,” a legendary figure who is supposed to have lived in the 7th century as a hermit in the neighborhood of Kuo-ch’ing Temple on the T’ien-t’ai Mountain in Chekiang. He was not a monk, nor yet a layman; he was just himself. He found a bosom friend in the person of Shih-te, who served in the kitchen of Kuoch’ing Temple. After every meal Han-shan would come to the kitchen to feed upon the leftovers. Then the two inseparable friends would chat and laugh. To the monks of the temple, they were just two fools. One day, as Shih-te was sweeping the ground, an old monk said to him, “You were named Shih-te’ (literally ‘picked up’), because you were picked up by Feng-kan. But tell me what is your real family name?” Shih-te laid down his sweeper, and stood quietly with his hands crossed. When the old monk repeated his question, Shih-te took up his sweeper and went away sweeping. Han-shan struck his breast, saying, “Heaven, heaven!” Shih-te asked what he was doing. Han-shan said, “Don’t you know that when the eastern neighbor has died, the western neighbor must attend his funeral?” Then the two danced together, laughing and weeping as they went out of the temple.

At a mid-monthly renewal of vows, Shih-te suddenly clapped his hands, saying, “You are gathered here for meditation. What about that thing?” The leader of the community angrily told him to shut up. Shih-te said, “Please control yourself and listen to me:

The elimination of anger is true shila.

Purity of heart is true homelessness.

My self-nature and yours are one,

The fountain of all the right dharmas!”Both Han-shan and Shih-te were poets. I will give a sample of Shih-te’s poetry here:

I was from the beginning a “pick up,”

It is not by accident that I am called ‘Shih-te.

I have no kith and kin, only Han-shan

Is my elder brother.

We are one in heart and mind:

How can we compromise with the world?

Do you wish to know our age? More than once

Have we seen the Yellow River in its pure limpidity!Everybody knows that the Yellow River had never been limpid since the beginning of history. So the last two lines were meant to convey that they were older than the world! Another noteworthy point in this poem is that even hermits—and Hanshan and Shih-te are among the greatest hermits of China—have need of like-minded friends for mutual encouragement and consolation. This is what keeps them so perfectly human.

From the poems of Han-shan, you will see that he is even more human than Shih-te. There were moments when he felt intensely lonely and homesick. As he so candidly confessed:

Sitting alone I am sometimes overcome

By vague feelings of sadness and unrest.Sometimes he thought nostalgically of his brothers:

Last year, when I heard the spring birds sing,

I thought of my brothers at home.

This year when I see the autumn chrysanthemums fade,

The same thought comes back to me.

Green waters sob in a thousand streams,

Dark clouds hang on every side.

Up to the end of my life, though I live a hundred years,

It will break my heart to think of Ch’ang-an.This is not the voice of a man without human affection. If he preferred to live as a hermit, it was because he was driven by a mysterious impulse to find something infinitely more precious than the world could give. Here is his poem on “The Priceless Pearl.”

Formerly, I was extremely poor and miserable.

Every night I counted the treasures of others.

But today I have thought the matter over,

And decided to build a house of my own.

Digging at the ground I have found a hidden treasure—

A pearl as pure and clear as crystal!

A number of blue-eyed traders from the West

Have conspired together to buy the pearl from me.

In reply I have said to them,

“This pearl is without a price!”His interior landscape can be glimpsed from a well-known gatha of his:

My mind is like the autumn moon, under which

The green pond appears so limpid, bright and pure.

In fact, all analogies and comparisons are inapt.

In what words can I describe it?With such interior landscape, it is little wonder that he should be so intensely in love with nature, for nature alone could reflect the inner vision with a certain adequacy. Some of his nature poems shed a spirit of ethereal delight. For example, this:

The winter has gone and with it a dismal year.

Spring has come bringing fresh colors to all things.

Mountain flowers smile in the clear pools.

Perennial trees dance in the blue mist.

Bees and butterflies are alive with pleasure.

Birds and fishes delight me with their happiness.

Oh the wondrous joy of endless comradeship!

From dusk to dawn I could not close my eyes.Only the man of Tao, the truly detached man, can enjoy the beauties of Nature as they are meant to be enjoyed. As to the others, they are too preoccupied with their own interests and purposes to enjoy the landscape of Nature. As an old lay woman called Dame Ch’en said, in a gatha she composed on seeing a crowd of woodcutters:

On the high slope and low plane,

You see none but woodcutters.

Everyone carries in his bosom

The idea of knife and axe;

How can he see the mountain flowers

Tinting the waters with patches of glorious red?

27. “Who is That Person?”

Yung-an Chuan-teng said to his assembly, “There is a certain person, who avers, ‘I do not depend on the blessing and help of the Buddha, I do not live in any of the three realms, I do not belong to the world of the five elements. The Patriarchs have not dared to pin me down, nor have the Buddha dared to give me a definite name.’ Can you tell me who is that Person?”

Wu-hsieh Ling-meh, a disciple of Shih-t’ou as well as of Matsu, was once asked by a monk, “What is greater than the heaven-and-earth?” He replied, “No man can know him!”

Although Ling-meh is usually listed as a disciple of Ma-tsu, he was actually enlightened at his encounter with Shih-t’ou. We are told that when he visited Shih-t’ou, he found him seated without paying any attention to him. So he started to go away. Shih-t’ou called after him, “Acarya!” As Ling-meh turned his head backward to the master, the latter scolded him, “How is it that from birth to death you have been doing nothing but turning your head and twisting your brains?” At these words, Lingmeh was thoroughly awakened to his self-nature, and stayed with Shih-t’ou.

The masters of Zen have referred to this self-nature by a great variety of names, such as “This One,” “That One,” “He,” “The Original Face,” “The True Man of No Title,” “The Independent Man of Tao,” “The Self,” and so forth. Some have even called him “The Family Thief.”

The whole meaning of Zen lies in the most intimate possible experiential recognition of “That Person” as your real Self. As to how does this real Self relate itself to God, I simply do not know. I know that the real Self is and that God is. But they are both inconceivable, and who can speak of their relation? In dealing with the things of God, all human words are, as Leon Bloy has so graphically put it, “like so many blind lions seeking desperately to find a watering place in the desert.” The Divine Word Himself is compelled to resort to parables and analogies. He speaks of the relation in organic terms as the vine and its branches. The whole living Tree is one-in-many and many-inone. It is at once non-dualistic and non-monistic. If the Zen masters insist on non-duality, they do not thereby commit themselves to monism, as some western students of Zen tend to think. This is all that I can say. Let me therefore stop here, remembering what Lao Tzu is reported to have said:

To know when to stop

To know when you can get no further

By your own action,

This is the right beginning!

28. A Buddhist Interpretation of a Confucian Text

The Chung Yung, or The Golden Mean says: “What is ordained of Heaven is called the Nature. The following of this Nature is called Tao. The refinement of Tao is called Teaching.” According to Ta-hui Tsung-kao, the first sentence corresponds to the pure Dharmakaya. The second sentence corresponds to the consummated Sambhogakaya. The third corresponds to the endlessly variable Nirmanakaya. If you can pierce through the barriers of words, you will find that this interpretation is not a far-fetched one.

29. Occasions of Enlightenment

It is not possible to describe satori; but to study the occasions of Satori is not only possible but extremely fascinating.

The upasaka Chang Chiu-ch’en was pondering a koan when he was in the toilet. Suddenly he heard the croak of a frog, and he was awakened, as evidenced by the following lines:

In a moonlit night on a spring day, The croak of a frog

Pierces through the whole cosmos and turns it into a single family!An ancient monk was studying the Lotus Sutra. When he came upon the passage that “All the Dharmas are originally and essentially silent and void,” he was beset with doubts. He pondered on it day and night, whether he was walking, resting, sitting or lying in bed. But the more he pondered, the more confused he became. On a certain spring day, an oriole suddenly burst into song, and just as suddenly the monk’s mind was opened to the light. He hit off a gatha on the spot:

All the Dharmas are from the very beginning

Essentially silent and void.

When spring comes and the hundred flowers bloom,

The yellow oriole sings on the willow.The sudden burst of song of the new oriole reminded him of the eternal Silence.

Not only sounds, but also colors can be an occasion of enlightenment. One master came to his enlightenment on seeing the peach blossoms. “Ever since I saw the peach blossoms, I have had no more doubts,” he used to say. Of course, he had seen peach blossoms previously to that happy occasion. But it was only on that occasion that he really saw them as they should be seen, that is, he saw them for the first time against the background of the eternal Void, as though they had just emerged from Creative Mind. On previous occasions, he had seen them vaguely as in a dream. But this time, as his inner spirit happened to be happily conditioned for enlightenment, the sight of peach blossoms opened his eyes to the Source of their beauty, so that he saw them not as isolated objects, but as lively spurts from the Source of the whole universe.

This reminds me of an interesting chat between Nan-ch’üan and his lay disciple Lu Hsüan. Lu was reciting Seng-chao’s saying:

Heaven and earth come from the same root as myself:

All things and I belong to one Whole.However, he did not really understand the full purport of it. Nan-ch’üan pointed at the peonies in the courtyard, saying, “The worldlings look at this bush of flowers as in a dream.” Lu did not see the point.

If Lu Hsüan had comprehended the truth of Seng-chao’s saying (which, by the way, was a quotation from Chuang Tzu), he would have seen Nan-ch’üan’s point. Only when you have realized that the cosmos and your self come from the same root, and all things and your self belong to one Whole, will you awake from your dream and see the peonies with wide-open eyes.

If we can think of God, not merely as the Supreme Engineer, but also as the Supreme Artist and Poet, Nature will reveal entirely new aspects to our eyes and regale our spirits with such enchanting beauty that we will feel as though we were living in the Garden of Delights. As the Sufi poet Sadi has put it:

Those who indulge in God-worship

Get into ecstasy from the creaking of a water-wheel.Some Zen masters have said that when a man is fully awakened, he can hear by his eye. The Psalmist was certainly such a man, who sang:

The heavens declare the glory of God,

And the firmament displays his art.

Day to day utters speech,

Night to night transmits knowledge.

30. Every Day a Good Day

Yün-men once put a question to his assembly: “I am not asking you about the days before the fifteenth (the full moon). I want you to tell me something about the days after.” Getting no word from the audience, he gave his own answer, “Every day is a good day.”

The full moon symbolizes enlightenment. The enlightened man is the free man. Being dead, nothing worse can happen to him. Being truly alive, nothing can be better. Not that he is immune to the buffets of fortune, but he knows that they cannot injure him any more.

Wu-men, the author of Wu-men kuan or The Gateless Gate, commenting on Nan-ch’üan’s aphorism that “Tao is nothing else than your ordinary mind, your everyday life,” produced a lovely poem:

Spring has its hundred flowers,

Autumn its moon.

Summer has its cooling breezes,

Winter its snow.

If you allow no idle concerns

To weigh on your heart,

Your whole life will be one

Perennial good season.The great paradox is that only a man who has no concern for his life can truly taste the joy of life, and only the carefree can really take care of others.

This reminds me of Pope John. What makes him so charming and so great? Is it not because he has lost himself in God? To him, “All days, like all months, equally belong to the Lord. Thus they are all equally beautiful.” On the Christmas of 1962, he said, “I am entering my eighty-second year. Shall I finish it? Every day is a good day to be born, and every day is a good day to die.”12 On the eve of his death, when he saw his friends weeping, he asked that the Magnificat be chanted, saying, “Take courage! This is not the moment to weep; this is a moment of joy and glory.” Comforting his doctor, he said, “Dear Professor, don’t be disturbed. My bags are always packed. When the moment to depart arrives, I won’t lose any time.”

True goodness is always beautiful and cheerful, even when one is on the brink of death. I can no longer doubt this after I have witnessed with my own eyes the death-bed scene of my dear wife, Teresa (d. Nov. 30, 1959). She was cheerful and thoughtful up to the very end. About two hours before her death, she whispered to our son Vincent, who was in her room together with Dr. Francis Jani saying, “The doctor has been standing so long that he must be greatly fatigued. Go bring a chair for him to sit down.” Dr. Jani thought that she was asking for something. So he asked Vincent what was her desire. When Vincent told him what she had said, the doctor was so moved that he went out immediately and wept. Later he told me that it was the first time in his thirty years of practice to find a dying person still so thoughtful of others. About an hour later, the doctor called us all in for the final farewell. She was in smiles, speaking to all our children one by one and blessing them and promising to pray for them in Heaven. I was simply dazed with wonder. Lowering my head, I prayed and offered her to Christ in the words of John the Baptist: “He who has the bride is the Bridegroom; but the friend of the Bridegroom, who stands and hears him, rejoices exceedingly at the voice of the Bridegroom. This my joy, therefore, is made full. He must increase, but I must decrease.” Suddenly I heard our children call me, “Dad, mommy wants to speak to you!” No sooner had I turned my eyes to her than she leaned forward and, holding my hands in hers, said cordially, “Till our reunion in Heaven!” This lifted my spirit to such a height that I forgot my sorrow!