ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

Philip Whalen (1923-2002)

禅心龍風 Zenshin Ryūfū (Zen Heart / Dragon Wind)

Tartalom |

Contents |

| Philip Whalen haikui Fordította: Terebess Gábor |

Haiku and Haiku-esque Poems Some major works:

Finger Pointing at the Moon: Zen and the Poetry of Philip Whalen PDF: The Zen of Anarchy: Japanese Exceptionalism and the Anarchist Roots of the San Francisco Poetry Renaissance PDF: On bread & poetry. A Panel Discussion With Gary Snyder, Lew Welch & Philip Whalen Jack Kerouac, The Dharma Bums (1958) PDF: Jack Kerouac, Big Sur (1962) PDF: Crowded by Beauty: The Life and Zen of Poet Philip Whalen |

Zenshin Philip Whalen (October 20, 1923—June 26, 2002) was an American poet and Soto Zen priest, a member of the Six Gallery reading of 1955 where the Beat movement famously began. Best known as a member of the Beat Generation, Whalen was also a key figure of the San Francisco Renaissance. Whalen received dharma transmission from Zentatsu Richard Baker in 1987, with whom he had followed from the San Francisco Zen Center to help establish Dharma Sangha in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Biography

Early Life

Philip Whalen was born October 20, 1923 in Portland, Oregon to Glenn and Phyllis Whalen. He belonged to a working class family and grew up in The Dalles, a small town on the Columbia River. Shortly after graduating high school he joined the United States Air Force, serving from 1943 to 1946.Following his service, he returned to college under the GI Bill, receiving his BA from Reed College in 1951 (his thesis a book of poems), where he met Gary Snyder and Lew Welch and also William Carlos Williams, who acknowledged Whalen as a poet while at Reed on a literary tour. He was also first introduced to Zen Buddhism at this time. He did odd jobs during this period, working part-time at the post office and also as a fire spotter at designated locations in area national parks during the summer.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s he traveled frequently up and down the West Coast, spending a good portion of that time in San Francisco. He participated in the Six Gallery poetry reading in 1955, meeting Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and Michael McClure.

1960 was a big year for Whalen, his first two books of poetry (Like I Say and Memoirs of an Interglacial Age) being published. His poetry was also featured in Donald Allen’s The New American Poetry, 1945—1960, one of the most successful anthologies of the post-WWII era with more than 100,000 copies sold.

At the suggestion of his friend and fellow poet Gary Snyder, Whalen spent 1966 and 1967 in Kyoto, Japan on grant money from the American Academy of Arts and Letters while teaching English. In Japan he began studying Zen Buddhism with more regularity. During this period of 1966 to 1967 in Japan, Whalen composed Imaginary Speeches For A Brazen Head (published in 1972), his second novel. Whalen continued living in Japan off and on until 1971, when he returned to the United States and, under the invitation of Zentatsu Richard Baker, began sitting at the San Francisco Zen Center (ordaining in 1973).

Following the scandal of 1984 at the San Francisco Zen Center, Whalen followed his teacher Zentatsu Richard Baker to Santa Fe, New Mexico and helped him establish Dharma Sangha. In 1987 Whalen received dharma transmission from Baker roshi, making him an independent Zen teacher within the Shunryu Suzuki lineage. In 1991 he returned to San Francisco and resumed practice at the San Francisco Zen Center, shortly after being installed as abbot at the Hartford Street Zen Center (HSZC) that same year.

Death

Whalen served as abbot at the Hartford Street Zen Center from 1991 to 1996, the year of his retirement from that position due to health concerns. He did, however, remain a resident teacher at Hartford Street until his death on June 26, 2002 at age 78. He also continued to write and have his work published while functioning as a Soto priest, though with lesser frequency. David Chadwick wrote at his website, cuke.com, “Philip’s time of death was June 26 at 5:50 a.m. I’m not sure what he died of and I don’t know if anyone is. It may be some sort of blood disease but he seemed to be dying of old age for years – with various complications. Anyway, he remained kind, thoughtful, and whimsical throughout these last years of illness and blindness.”

Cf. http://www.cuke.com/sangha_news/Philip%20Whalen/Whalen%20link%20page.html

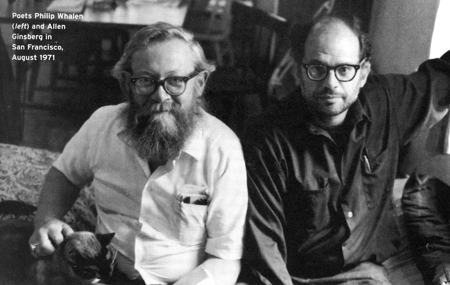

Whalen & Allen Ginsberg in San Francisco, August 1971

Philip Whalen (full name Philip Glenn Whalen) was an American poet, Zen Buddhist, and one of founders of the West Coast Beats, who played an important role in the San Francisco Renaissance and the Beat generation. While at Reed College, he met Gary Snyder and Lew Welch. After graduation Welch left for advertising industry and Whalen and Snyder joined Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Michael McClure and Philip Lamantia for the historic Six Gallery reading. Young poets, most of who had never met before, took the West Coast by storm and soon became celebrities. Whalen's poetry was soon published in the "Evergreen Review" and in the 1959 Grove Press anthology, "New American Poetry." Like others in the group, he rejected structured, academic writing and explored different forms. Eventually, he became known for his ironic, dry and witty humour and realistic portrayal of life. His topics are full of details depicting annoyances, joys and sudden wake-up calls.

In 1973, soon after his travel to Japan, he converted to Zen Buddhism, took a name Zenshin Ryufu "Zen-mind-dragon-wind" and became a Zen Buddhist monk. As a head monk of the Santa Fe, New Mexico order in 1984 and a leader of the Hartford Street Zen Center in San Francisco, he undertook several tasks, including caring for AIDS patients in San Francisco. Whalen was inspiration for two characters in Jack Kerouac's novels: Ben Fagan in "Big Sur" and Warren Coughlin in "Dharma Bums."

http://writershistory.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=726&Itemid=26

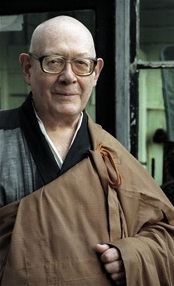

Philip Whalen at Hartford Street Zen Center, October 1977

Philip Whalen

About Writing and Meditation

Reprinted from Beneath a Single Moon: Buddhism in Contemporary American Poetry, edited by Kent Johnson and Craig Paulenich, Shambhala, 1991.

http://jacketmagazine.com/11/whalen-writing.html

I thought that I'd write books and make money enough from them to travel abroad and to have a private life of reading and study and music. I developed a habit of writing and I've written a great deal, but I've got very little money for it.

With meditation I supposed that one could acquire magical powers. Then I learned that it would produce enlightenment. Much later, I found out that Dogen is somewhere on the right track when he tells us that the practice of zazen is the practice of enlightenment. Certainly there's no money in it. Now I have a meditation habit.

Jack Kerouac said that writing is a habit like taking dope. It's a pleasure to write. I usually write everything in longhand. I like the feel of the pen working on the paper.

In my experience these two habits are at once mutually destructive and yet similar in kind. I write for the excitement of doing it. I don't think of an audience; I think of the words that I'm using, trying to select the right ones. In zazen I sit to satisfy my sitting habit. It does no more than that. But while sitting, I don't grab onto ideas or memories or verbal phrases. I simply watch them all go by. They don't get written; they don't (or anyway, very seldom) trip the relay on my writing machinery. Considering that I've spent more days in the past fifteen years sitting zazen than I have spent in writing, it's little wonder that I've produced few books during that time.

I became a poet by accident. I never intended to be a poet. I still don't know what it's all about. If I wrote poetry at all, it's because I could finish it at the end of the page. Maybe it would run halfway down the next page, but it would come to a stop. What I wanted to do with writing was to write novels and make money like anybody else. And now I find myself in this ridiculous industry of writing these incomprehensible doodles, and why anybody's reading them I can't understand.

As far as meditation is concerned I'm a professional. I've been a professional since 1973. And that's my job. I find it very difficult to sell. And that's interesting; that's another job I have, to sell you on this idea that it's good to sit. Maybe that's where the poetry comes into all this, that it has to be an articulation of my practice and an encouragement to you to enter into Buddhist practice. To get yourselves trapped into it I hope. And then try to figure out how to get out of it. It's harder to get out of Buddhist practice than it is to get out of writing poetry.

I write very little nowadays. There is a journal in which I write things like "the sun is shining" or "Michael McClure was in town and we had a nice time" or "the flowers are blooming." And so I don't have much to say because I talk all the time. I have to give lectures, I participate in seminars, and I have not much chance to wander up and down a hillside picking flowers and picking my nose and scratching my balls and what-not. And thinking of hearing, having a chance to hear what's going on around me, or hearing people in restaurants or on a bus. There are no restaurants in Santa Fe worth sitting in, there are no buses at all. So I don't hear anymore, hardly at all, unless I travel. I was recently in New York and around, and now I'm here at Green Gulch Farm, and it's interesting to hear what's going on outside. While somebody was talking there was a robin outside raising hell. But that doesn't mean anything. I mean I'm not about to write a poem on the subject of so-and-so talking, while a robin outside was raising hell.

And so I'm here under false pretences. You must deal with that however you can. I'm quite willing to talk to people and explain things to them if they have questions. Or I might be sitting doltishly looking out the window. So it will be necessary for you, if you want something from me, to try to get it by asking questions. I'm not about to offer anything, I don't have anything to offer. I'm sorry - that's the "emptiness" part.

I think there's a great deal of misunderstanding about what emptiness is, the idea that emptiness is something that happens under a bell jar when you exhaust all the air from it. That's not quite where it's at as far as I understand it. The emptiness is the thing we're full of, and everything that you're seeing here is empty. Literally the word is shunya , something that's swollen up; it's not, as often translated, "void." It's packed, it's full of everything. Just as in Shingon Buddhism, the theory that everything we see and experience is Mahavairochana Buddha, the great unmanifest is what we're actually living and seeing in. Wallace Stevens said, "We live in an old chaos of the sun." Well we're living in a live chaos of Mahavairochana Buddha. What are you gonna do with it? How are you gonna handle that?

My Buddhist name is Zenshin Ryufu, which is very impressive. The reason that you have a name like that is that you keep forgetting it and it makes you wonder about why you got it and why it's for you, because it's a very exalted idea. Zenshin means "meditation mind" and it's also a Japanese pun. It means something like "complete mind." There's also a zenshin essay by Dogen. Ryufu is two Chinese characters that literally mean "dragon wind," but in Chinese literature I found out it means "imperial influence" (the dragon stands for the Chinese emperor). It's pretty complicated, and you wonder, well, what does that have to do with me? Four words - Zen- Mind- Dragon- Wind. What in the world, what connection does that have with this individual who has received this name and is ordained as a monk? So that is a problem that becomes more or less clear as you continue being a monk - what your name is. And of course names and poetry all come together. Gertrude Stein says poetry is calling the name of something. That's what we do all the time, actually - call ourselves. There's the story of the Zen master who every day would call his own name. He'd say, "Zuigan!" And he'd say, "Yes!" "Zuigan! Don't be misled by other people!" Of course the other people were Zuigin too.

I like the idea somebody mentioned of erratic practice. It immediately reminded me of rocks that were left around when the glaciers receded. A lot of times setting out in a field there are no other rocks. It's a very strange appearance. You can't account for the rock's position unless you remember the glacier that carried the rock there and then went away. Zazen is slow but leaves erratic boulders.

I have a number of fancy titles at the Dharmasangha (Zen Brotherhood) in Santa Fe. But when push comes to shove it means that I'm the person who goes down and does the opening ceremony in the zendo (meditation hall) every morning and sits two periods. And then I go down again at 5:30 in the evening and sit again with whoever shows up. And the rest of the time I study. We have two seminars a week with Baker Roshi on the koans in the Shoyoruko as translated by Thomas Cleary. I've also been studying with Baker Roshi closely for the last three years with the intention at last of trying to become a Buddhist teacher, to help get this show on the road, which is still very precarious in this country. The chances as I see it of Buddhism simply becoming something that people do on Sunday just like Methodism or Catholicism are very strong. But I hope that there will continue to be centers in the country like Tassajara, or Shasta Abbey, or Mt. Baldy. There will be these hidden spots around the country where people can hide out and do more serious, concentrated practice, to keep the door open for everybody to get the chance to try it out, find out what it's like to not do anything except follow a particular schedule and do a lot of sitting and a lot of physical work. This is something that I think is necessary in order for human beings to go on being human beings. So far all we've been able to invent in the United States is the business of building small cabins in the woods and going there to hide out, then come back and write a book about it.

That practice, that sort of individual, hermit, erratic practice, is something that's really important. The danger of Zen Centers or monasteries is that people will take them seriously as being real. We should find our own practice; we might start out in an official place, but we should discover somehow that we don't need official institutions. It's exactly like Lew Welch says in his poem about the rock out there, the Wobbly Rock, "Somebody showed it to me and I found it myself." The quote isn't exact. Lew was in erratic Zen practitioner who was a great poet.

The real tension, I think, is between official poetry, the kind that we're taught in school and is kept in libraries, and the kind we really believe in - what we are writing and what our friends write. The same thing holds for meditation: what we discover for ourselves and learn. At some point you can forget it and go off and make a pot of spaghetti. We used to do go down to Muir Beach years ago to gather mussels off the rocks. We'd build a bonfire, put seaweed on the fire to steam the mussels. We'd eat them, then jump up and down in the waves and have fun. That was enough. Probably enough. Or too much. Oh, I guess Blake said it, "Enough, or too much." That's all.

Finger Pointing at the Moon: Zen and the Poetry of Philip Whalen

by Jane Falk

In: The emergence of Buddhist American literature, State University of New York Press, Albany, NY, 2009, pp. 103-122.

http://www.watflorida.org/documents/The%20Emergence%20of%20Buddhist%20American%20Literature_Whalen-Bridge_Storhoff.pdf

Philip Whalen holds a unique place in modern American poetry. Best

known as one of the original members of the Beat Movement, as a Zen

Buddhist he also enacted the traditional role of poet-priest. However, even

before Whalen entered formal practice in the 1970s, he had been linked

to Zen by fellow poets and critics. Allen Ginsberg, for example, describes

Whalen in 1955 at the seminal Six Gallery poetry reading in San Francisco

as “a strange fat young man from Oregon—in appearance a Zen Buddhist

bodhisattva,” who read poetry “written in rare post-Poundian assemblages

of blocks of hard images set in juxtapositions, like haikus.”1 Whalen was

also included in the summer 1958 Zen issue of the Chicago Review with

Gary Snyder, D.T. Suzuki, Alan Watts, and Jack Kerouac, among others.

Unlike fellow poet Gary Snyder, however, he did not participate in traditional

Zen practice under a teacher at this time, but gained his understanding

of Zen from books and friends. How did Zen inform Whalen’s poetry,

and how did his use of Zen change over time?IN SEARCH OF “REAL SELF”

Whalen’s early interest in Zen can be seen as proof of his avant-garde status

and as a way of distancing himself from identities available to mainstream

American writers in the 1950s, as well as a means by which to access what he

called “Real self.” One might even contend that Whalen’s allusions to Zen in

his early poetry were appropriative, during a time when Zen was a popular

force in American culture especially among avant-garde artists and poets. A

shift occurs both in purpose and emphasis in Whalen’s poetry from the 1950s

to the 1970s, however, when his formal practice begins, and he is ordained

as a monk at the San Francisco Zen Center. Poetry becomes for Whalen an

expression of his practice and a way to encourage others (implying the Buddhist

concept of upaya or skillful means by which bodhisattvas or enlightened

ones strive to use all possible means to bring others to enlightenment).2

This shift is paralleled by a second one in emphasis and content, from more

direct allusions to Zen in earlier poems to more subtle and less specific allusions

later: poetry as practice versus practice as poetry.

Explicating the title of one of his early poems, “The Slop Barrel: Slices

of the Paideuma for All Sentient Beings,” is a way to understand Zen as part

of his avant-garde project. Ostensibly this poem is about growing up and

gaining knowledge; however, the way the title juxtaposes several kinds of

language (colloquial, Greek, and Buddhist) demonstrates a new vocabulary

for poetry. The poem also includes allusions to the Zen kōan and is

a way to wake readers up to a “new comprehension” in the United States

post–World War II when Eastern cultural values were gaining interest.3

A pertinent discussion of Whalen’s interest in Buddhism occurs in a letter

of July 26, 1960, to Allen Ginsberg where he describes what the examples

of Buddha, bodhisattvas, and Zen practitioners mean to him and that the

real question for a Buddhist is Waht [sic] am I doing? The answer is to “eat

that old, imaginary self each one of us imagines we ‘have’” in order to make

way for the “Real self,” “our true identity,” which will act as an alternative to

identities available to Americans in the 1950s. He hypothesizes that Ginsberg

may not like the terms he is using, noting that he wants to find “new

ones, make new stories, poems, metaphors of all this which you & anybody

else WILL dig, so’s you can get started on the way to figuring out for yourself

what you are, what is Heaven (or Enlightenment, or Real, or whatever).”4

Whalen’s method in writing poetry expressive of the “Real” also puts

Western philosophical issues of perception, identity, consciousness, and

language (what might be considered epistemological questions for a Eurocentric

writer) into a Buddhist context using tenets, practices, scriptures,

and literature associated with Zen.5 As Whalen put it in a 1975 interview with

Lee Bartlett, the ideas about Zen “began to find their way into the poetry.”6

He often organizes his early poems around such questions, which also act

as his personal kōan problems. Zen kōan practice usually involves a teacher

giving a kōan or problem to a student to solve. The student must then provide

an individual response found while meditating, as well as a capping

verse, which demonstrates the solution to the problem and the student’s

level of understanding.7 In the process of writing the poem, Whalen works

out an answer or response to his questions while simultaneously involving

readers, his intent being to change perceptions about the nature of reality.

Whalen’s statement of poetics in Donald Allen’s New American Poetry

Anthology that describes poetry as a “picture or graph of a mind moving”

also recalls Zen and its practice of seated meditation: the practitioner sits

silently, following the breath, aware of the mind’s movement.8 As Whalen

adapts this practice to poetry, the content of the poem is the content

of Whalen’s mind or vice versa, recorded as he observes it, including the

sounds and activities of the world around him as he writes. These reality

bits might be considered the found text and found sound of his poems. His

statement of poetics also demonstrates the Buddhist concept of pratitya

samutpada, or “conditioned arising,” the mutual conditioning of all things.

This is best expressed in the Avatamsaka Sutra’s teaching of interdependence

and is symbolized by the Net of Indra in which each object in the

universe is able to reflect and connect with all others.9 In this way Whalen

seeks to resolve the tensions he feels between inner and outer worlds, the

investigation of which is a common thread in his poems and a way of presenting

and understanding the “Real.”THE REED CONNECTION AND ZEN ROLE MODELS

To better gauge Whalen’s early understanding of Zen, it is useful to look at

his first encounters with Buddhism beginning in the 1940s and 1950s and

the models he used as inspiration. His was a working-class background.

Raised as a Christian Scientist in The Dalles, a small town in Oregon,

Whalen went into the Army from 1943–1946, afterward attending Reed

College on the GI Bill. There he met Gary Snyder who shared his discovery

of R.H. Blyth’s four-volume study of haiku and the writings of D.T. Suzuki

with Whalen and fellow Reed student and poet, Lew Welch.10 Once in the

Bay Area after the Six Gallery reading, Whalen followed up his earlier interest

in Zen by meeting Alan Watts and Albert Saijo. Although Whalen had

already started the practice of sitting meditation on his own, Saijo taught

Whalen and others how to sit with proper form and for longer periods of

time at the informal zendo, Marin-an.11 In addition, Whalen gained much

information about Zen, its literature, practice, and the use of Zen accoutrements

from correspondence with Snyder during the latter’s stay in Japan

1956–1958 and again 1959–1964.

At this time, Whalen also modeled himself after the related roles of

Chinese poet-scholar and poet-priest. The T’ang and Sung poets he chose

to emulate, such as Li Po, Po Chu-I, or Su Tung-po, were not only renowned

poets, but were also interested in Daoism (the former) and Buddhism (the

two latter), specifically Ch’an or Zen Buddhism. In addition, the lifestyle

of Chinese poets would have appealed to Whalen with their fondness for

drinking wine, reciting poetry with fellow poets, and appreciating nature.

As Whalen put it in a 1991 interview, part of Zen’s attraction was the fact

that it “allowed people to be poets and painters—or at least I thought it

did—these were acceptable creatures to be Buddhist practitioners. . . . You

could be crazy and still be a Buddhist of some stripe or other.”12

An example of Whalen’s feeling of kinship with such poets occurs in a

letter from Whalen to Snyder of August 7, 1954, in which he hypothesizes

about his proposed stay in Newport, Oregon: “So maybe I shall be Marshal

of Sui, or whatever it was Mr. Po did in the Provinces.”13 This probably

alludes to Po Chu-I who was exiled because of poems written critical of the

political regime of his day. By making this comparison, Whalen indirectly

demonstrates his feeling of exile from American society by both his lifestyle’s

implicit and his poetry’s explicit critique of middle-class attitudes

toward work and money in the 1950s.

Whalen’s poem of 1958, “Hymnus Ad Patrem Sinensis,” translated as

“Hymn to the Chinese Forefather,” pays homage to and expresses his feelings

of kinship with “ancient Chinamen”:Who left me a few words,

Usually a pointless joke or a silly question

A line of poetry drunkenly scrawled on the margin of a quick

splashed picture. . . . (2–5)Here Whalen suggests the irrepressible nature of such poets with their

cheering as the world “whizzed by,” going to “hell in a handbasket,” eventually

“conked out” among cherry blossoms and winejars. The carefree attitude

of these poets is echoed in the poem’s free-verse form, the casualness

of its off-rhyme, and its colloquial tone. With the poem’s last line, “Happy to

have saved us all,” Whalen suggests a double meaning. Either poets as priests

or bodhisattvas wrote poetry to express and transmit their Buddhist understanding

or lay Buddhists wrote life-enhancing poetry for readers. The line

implies that poets, themselves, can save people, although its playful tone suggests

that readers should not take this easy platitude too seriously.POETRY AS PRACTICE

“Sourdough Mountain Lookout” is a poem that more directly associates

Whalen with Zen for his 1950 audience through its publication in

the Chicago Review Zen issue and its Buddhist references. Whalen incorporates

Zen philosophy and Buddhist scriptures in the poem as a way

to understand relations between the speaker’s inner and outer worlds,

especially the way in which all entities interpenetrate in a world paradoxically

both full and empty, expressed as one past-present-future-memorymoment.

The poem presents a fire lookout’s experiences on Sourdough

Mountain, similar to Whalen’s own experience during the summers of

1953–1955 in Washington’s Mt. Baker National Forest. It begins as the

speaker (understood as a kind of Buddhist hermit poet) climbs up the

mountain and describes his mountaintop world in company of bear,

mice, flies, mountains, and stars. What to one contemporary critic was

the speaker’s passivity, from a Buddhist point of view could be considered

mental action: observation of surroundings juxtaposed with the speaker’s

memories, including voices from the past and quotes from books the

speaker is reading.14

Toward the end of the poem, the speaker’s reflections become more

focused on Buddhist tenets, as he quotes the Buddha and compares the

encircling mountains to the circle of beads of a Buddhist rosary, in the

empty center, the meditator. Attention then shifts to the next morning

and a description of a souvenir rock of granite and crystal brought back

from a walk:A shift from opacity to brilliance

(The Zenbos say, ‘Lightning-flash & flint-spark’) (158–159).This phrase, familiar to Zen practitioners, suggests the experience of

enlightenment.15 The image’s power is to suggest the sudden change in

quality of life from unenlightened to enlightened, although physically the

practitioner (like the rock) is the same. The speaker then presents another

shift or turning point in the next stanza’s statement of both the essential

fullness and emptiness of the world:What we see of the world is the mind’s

Invention and the mind

Though stained by it, becoming

Rivers, sun, mule-dung, flies–

Can shift instantly (161–165).These shifts are followed by a five-line refrain, which both expresses

the speaker’s situation in American slang and is Whalen’s translation of the

concluding mantram of the Prajnaparamita Sutra, one of the most important

scriptures of the Zen tradition, providing in concise form the teaching

of form in relation to emptiness:Gone

Gone

REALLY gone

Into the cool

O MAMA! (167–171)16The view from the lookout is full of objects, thoughts, and memories, but

from the point of view of the sutra and Zen, all are equally empty or “gone.”

However, even without the Buddhist association, these five lines could logically

refer to departure from the lookout at the end of summer. The colloquialism,

gone, is slang for “the most, the farthest out . . . ‘out of this world.’”17

For Whalen, slang with its spontaneity and immediacy is adequate or even

better to express this Buddhist realization. Going out of one’s mind and

losing normal consciousness is equivalent to the sutra’s meaning.

However, a more evolved understanding of emptiness for D.T. Suzuki

includes seeing things as they are.18 Whalen includes this understanding,

too, as the speaker closes the lookout:Thick ice on the shutters

Coyote almost whistling on a nearby ridge

The mountain is THERE (between two lakes) (150–152).Here the capitalized adverb is a simple and matter-of-fact place marker.

More importantly, through the variety of levels and kinds of language play

here, Whalen also narrows the gap between spirituality and ordinary life,

one of Zen’s goals.

Whalen’s rather enigmatic closing lines for the poem hint at a Zen

paradox:Like they say, ‘Four times up,

Three times down.’ I’m still on the mountain. (172–173)The couplet could mean that though he’s coming down from the mountain,

his mind will still be on the peak, informed by insights gained there

or that he is always in a mountain state of mind. The couplet also acts as a

kind of capping verse to the speaker’s experience on the mountain and his

attempt to understand the relationship between inner and outer worlds and

the seeming opposites of form and emptiness, the poem’s kōan problem.

These lines also demonstrate Whalen’s adaptation of haiku in his work,

a poetic form associated with Zen. Although Whalen creates some short

poems, which he titles haiku, more often he incorporates haiku-like stanzas

into longer poems often as a way to conclude with some turn or double

meaning as in “Sourdough Mountain Lookout.”19 Haiku often contain

such turning points, especially between second and third lines. Whalen’s

use of haiku may owe much to the ideas of R.H. Blyth who relates haiku and

the Zenrinkushu, the Zen anthology of capping verses. For Blyth, haiku can

express temporary enlightenment as can kōan practice. D.T. Suzuki also

connects Zen and haiku with the idea that haiku are expressions of “inner

feeling absolutely devoid of the sense of ego,” a similar kind of response to

the world required in solving a kōan.20

However, the kōan would prove more compelling for Whalen at this

time. Other poems of this period have even stronger allusions to kōan

practice in the way Whalen organizes them around kōan-like questions

of perception and identity, the poem, itself, becoming a way Whalen, and

by extension his readers, work out specific problems of life through art.

“Metaphysical Insomnia Jazz. Mumonkan xxix,” of 1958, demonstrates

this method, its title referring to the 29th kōan of the Mumonkan or Gateless

Gate, one of the most important kōan collections in Zen literature.21 The

poem juxtaposes the speaker’s musings and memories in a free associative

manner with phrases from the kōan printed in capital letters to contrast

with the rest of the poem’s lowercase type, further sectioning and differentiating

between points of view with thick, black lines for a jazzy effect.

In this kōan two monks argue about a flag moving in the wind. One claims

that it is the flag moving, the other that it is the wind. The Sixth patriarch,

Hui-neng, passing by, overhears the argument and comments that it is mind

not wind or flag that moves; the kōan thereby demonstrates the relation of

mind and phenomena.

Whalen begins his poem with an insomniac speaker, a cat, and a little

ditty about a love named Kitty, followed by allusion to prayer-flags near

Nanga Parbat, a mountain in the Himalayas. These flags bring to mind the

wind moving and the 29th kōan, which the speaker may have been contemplating.

Next the speaker recalls a driver hypnotized by windshield wipers

(representing the flag moving). The speaker’s free association in the poem

also enacts mind’s movement (Hui-Neng’s response) concluding with a

couplet which also acts as a capping verse:& now I’m in my bed alone

Wide awake as any stone (20–21)The singsong rhythm here belies a serious tone, while simultaneously

conveying the paradoxical aspect characteristic of kōans. The fact that

the speaker is as wide awake as a stone is from the Western view irrational

because stones are not sentient. However, from the Zen point of

view, stones are equally part of the interpenetrating lifeworld. Considered

as a capping phrase, this couplet is also spontaneous and grounded

in the moment enough to qualify as the speaker’s own response to the

29th kōan.

Original face is perhaps the most important kōan for Whalen in regard

to the questions of perception and consciousness he posits in his early

poetry, necessitating a search for the real as opposed to the illusory in

regard to the self or “I.”22

The question of “’what was your original face, before you were conceived,’”

is asked directly in “I Return to San Francisco,” a poem in which

the speaker returns to the city from his isolation in Oregon. Although these

are questions any human being faced by an identity crisis might ask, they

also relate to kōan practice. Indeed according to some commentaries on the

kōan, such personal questions are legitimate ones on which to meditate.

The most structurally exciting of these identity poems is “Self-Portrait,

from Another Direction,” a poem about a somewhat ordinary day in the life

of the poem’s speaker. Here the search for original face leads to self-portraiture,

perhaps a contradiction in terms for a poet with Buddhist aspirations

because for Buddhists the ego or ”I” is illusory. This interest may also

demonstrate, however, Whalen’s appropriation of Buddhist tenets without

the backing of formal Buddhist practice at this time. The poem begins with

the speaker in bed as he wakes up and simultaneously contemplates and

remembers taking a trip downtown. Future and past meet in present. The

body of the poem not only describes these trips, but shows how easily the

mind can travel with or without the body. In the poem’s dynamic movement

from inside to outside, mind to world, and room to town, the poet

seeks to re-create the dynamics of interpenetrating space and time.

The poem ends with the speaker contemplating his face in the mirror

(a self-portrait), which provides closure by returning the reader to the

poem’s beginning: “Into the mirror (NOW showing many men) all of

them ‘I.’” This circularity also illustrates the Buddhist concept of pratityasamutpada

or “conditioned arising,” which explains how individual beings

are caught in karmic cycles of existence. It is visualized as a chain of twelve

links, beginning with ignorance, leading through desire and death with

subsequent rebirth to a new round unless enlightenment takes place and

the chain is broken. The poem in following the speaker’s thought process,

emphasized by line breaks and indentations, is also similar to the way a

Buddhist practitioner watches his or her thoughts go by without attachment

in meditation, recalling Whalen’s statement of poetics. From this

perspective, the poem may be read as a kind of Buddhist meditation on the

way thought becomes present on the page.

In regard to this poem, Snyder comments in a 1960 letter to Whalen

that he found it to be an “excellent rephrasing of the Lankavatara [Sutra]

(with Kegon undertones, especially the end).” The comment on Kegon

“undertones” may relate to this Mahayana Buddhist school’s interest in the

constitution and perception of reality, demonstrated by its privileging of

the Avatamsaka Sutra that teaches the “mutually unobstructed interpenetration”

of all things and “that buddha, mind, and all sentient beings and

things are one and the same.”23

In addition, the speaker’s aim is to truly record the minute particulars of

his days, “NOW,” as he phrases it in the poem’s last line. Such effort is similar

to the poet’s difficulty in writing such a realistic poem and of literally enacting

in words the “mutually unobstructed interpenetration” of all aspects of

the speaker’s reality as separate, yet simultaneous with mind. This difficulty

with writing and the physical toll it takes may relate not only to writer’s block

or issues of originality, but to the ideas of the Lankavatara Sutra that words

are not or can never be the truth. They can only point to it like a finger pointing

toward the moon. The dilemma is that the translation of experience into

words removes the poet-practitioner from the present moment in which he or

she (as “Real self”) is ideally to live if truly enlightened.KYOTO INTERLUDE

The shift in Whalen’s work to poems truly grounded in Zen practice may

be demonstrated in later poetry, especially as he began to spend more time

as Zen practitioner than as poet. An interim period for this is Whalen’s stay

in Japan in the late 1960s where, as he states in a 1999 interview with David

Meltzer, he began to sit “seriously.”24 Some poems from his Kyoto days

seem written from the perspective of a sightseer or an outsider looking in at

a fascinating spiritual and aesthetically pleasing culture. Often the speaker

of such poems walks and observes ceremonies and the beauty of Buddhist

temples or sits and observes himself and others in the coffeehouse milieu.

Other poems address Buddhist concerns more directly.

One of Whalen’s most important poems from this period and one that

seems at first glance to be primarily political, is “The War Poem for Diane

di Prima,” written as a protest of the Vietnam War, which was going on

while Whalen was living in Japan. Much of this poem condemns the war

and the United States government for sending young men to die in Vietnam

for money and power, emphasized in the poem’s last lines:Nobody wants the war only the money

fights on, alone. (168–169)The poem’s second section, however, titled, “The Real War,” describes a

war fought at all times by all humans. The section begins as the speaker

watches water dropping down a rain-chain, which he free-associates with

the twelve links in the Buddhist chain of causation. These stages are capitalized

in the poem for emphasis and presented in list form moving from

ignorance through desire to old age and death. The speaker privileges revolution

over war, calling for a change in consciousness (recalling Whalen’s

interest in poetry as a valid and important way to make that change).

Other shorter poems provide more direct meditations on the nature

of reality, while also bringing the speaker of the poem to new levels of

awareness, an example being, “Walking beside the Kamogawa, Remembering

Nansen and Fudo and Gary’s Poem.” The sight of stray cats along

the river brings to the speaker’s mind Gary Snyder’s dying cat and the

meaning of life and death, as well as the words of the Soto Zen teacher of

San Francisco Zen Center:Suzuki Roshi said, ’If I die, it’s all right. If I should

live, it’s all right. Sun-face Buddha, Moon-face Buddha.’ (15–16)Here, Suzuki Roshi alludes to the 3rd kōan from the Hekigan roku, another

famous Zen kōan collection.25 This kōan forces the student to confront

duality and to question the making of dualistic distinctions. The poem

ends with a two-line capping phrase:We don’t treat each other any better. When will I

Stop writing it down. (18–19)This last line break foregrounds the speaker’s query become admonishment

(“stop writing it down”), implying that practice is more important

than writing. The speaker’s response also involves the realization that

acceptance of the nonduality of life and death is not something that can be

understood intellectually or even expressed in words. The poem ends with

a postscript and the word, hojo, the Japanese term for a monk’s cell, suggestive

of Whalen’s future path.

In this regard, Whalen’s failure to begin formal practice during his stay

in Japan is hinted at in several poems from this period. For example, “The

Dharma Youth League” equates the failure of “several thousand gold buddhas”

to do no more than sit during World War II with that of the Buddha’s

and Whalen’s own, ending,Does Buddha fail. Do I.

Some day I guess I’ll never learn. (6–7)Here, the way declarative statements also ask questions and the last line

juxtaposes optimism with failure creates a paradoxical ending that calls the

concept of failure, itself, into question.PRACTICE AS POETRY: THE 1970S AND BEYOND

In the 1970s, Whalen formally became a Zen practitioner at the San

Francisco Zen Center, and his role began to shift from poet to priest. He

was given dharma transmission by Richard Baker Roshi in 1987 and was

invested as Abbot of Hartford Street Zen Center in 1991. One consequence

of his increased commitment was a decrease in poetic output in the 1980s,

due to concerns and obligations to spend more time in meditation and

teaching. This is especially true in the 1990s when his deteriorating health

and failing eyesight became additional hindrances to writing.26 Thus some

might consider Zen’s influence on Whalen as poet to be a negative one,

especially in regard to the long poem as a form that seems to drop from

his practice. However, Whalen continued to write short poems, often of

a commemorative and occasional nature, most notably poems of the late

1970s and 1980s collected in Some of These Days, 1999. In addition, he

became involved in new poetic endeavors as one of the co-translators for

Kazuaki Tanahashi’s project to translate the teachings of Soto Zen master

Dōgen.27 Significantly, Whalen’s shorter, tighter, yet expressive poetry

might be considered more in keeping with Dōgen’s work and that of the

Zen and Japanese poetic traditions in general, bearing out the contention

that from a Zen perspective less is more.

Although Whalen never actually claimed the role of Zen poet, as a

Zen priest he did make several statements about how his poetry might

be understood in relation to Zen teachings. In a 1991 interview after his

investiture as abbot of Hartford Street Zen Center, Whalen was asked by

Schelling he ever thought of his poems as “Dharma teachings.” Whalen’s

response was “In a way, yeah . . . Maybe it’s possible that somebody who

is already practicing might get the point as it were. And other people who

weren’t practicing might say, ‘What is this practice thing about, what

is Zen about?’” (“PW:ZI” 231). Later in the interview Schelling asks

whether Whalen’s poetry comes out of contemplative states or whether

they are in the tradition of sutra or kōan material, and Whalen responds

that much of what he has written was because he “saw things or heard

things immediately” or that “something caught my attention,” to which

Anne Waldman adds that attention, itself, can be considered a contemplative

state (“PW:ZI” 232–233).

A number of poems that express such a state, heightened by meditation,

come from Whalen’s Tassajara period collected in Enough Said.28 For

example, “’Back to Normalcy’” begins as the speaker’s ear “stretches out

across limitless space and time” (1) to hear even a fly walking while his eye

catches the cat’s eye. The rest of the poem is made up of ambient sounds

and sights: wind chimes, generator noise, snatches of conversation, and

sunshine. The poem ends with an observation reminiscent of the way earlier

poems close with a capping phrase while the rhythm of the lines adds

emphasis and echoes meaning:Brown dumb leaves fall on bright ferns

New and thick since the fire (13–14)The suggestion here is that everyday life equates with normalcy experienced

as process and change; eventually the ferns will grow back after the

fire, the fire in question being the great fire at Tassajara of 1977. The poet

presents this flow and interpenetration of life on various levels (plant, animal,

and human), all interacting in the poem through the speaker’s consciousness.

However, the fact that the poem’s title is in quotations, a scrap

of conversation overheard by Whalen, perhaps, draws attention to and

questions accustomed language use. Is there a state of normalcy, or is each

moment unique? This is another way of questioning dualistic thinking

with the understanding that life is neither and both simultaneously.

Another poem from this period, “What’s New?” also builds on the

speaker’s observations moving from outer to inner worlds, as he notes his

reactions to happenings of daily life. Again the juxtaposition of objects,

sensations, memories, and associations demonstrate and follow the mind

in movement, part of the way Whalen’s poetry can model a Buddhist perspective

for both practitioners and nonpractitioners. The poem begins as

a kimono falls from a hanger seen by the speaker not as a cause for anger,

but as visual excitement: “Falling timelessly (if I say so) to the closet floor”

(8). A few weeks later a similar experience when rug buckles and table falls

causes an opposite reaction of chaos and the speaker’s impulse to “(furious)

grab, rush” (11). This is followed by another shift:Fill in the blanks later, unexpected brilliant excursions

And back again to the central trunk or channel, (15–16).Here, Whalen refers to the practice of meditation in which wandering attention

and thoughts are brought back to the center attached to stable spinal

column or “central trunk.” The poem ends with more mind excursions, as

the falling kimono recalls waterfalls, first that of a PG & E station in San

Francisco and then the waterfall that Buddhist monk, Morito Shonin, sat

under in penance to Myo’o Fudo after killing his love. This anecdote may

also relate to the Tassajara fire because Fudo is the god associated with fire.

Later poems of the 1980s, however, become even more spare and

seemingly matter of fact, yet layered with meaning. For example, the 1986

poem, “On the Way to the Zendo,” describes Whalen’s life in New Mexico

at Cerro Gordo Temple and South Ridge Zendo where he followed Richard

Baker Roshi in 1984.29 This short poem of five lines has a haiku-like form

juxtaposing the speaker’s outer and inner worlds. It begins with physical

sensations of the outside world, wind blowing leaves and ducks quacking,

and then moves inward in its concluding lines:SOME VERSIONS OF THE PASTORAL whistle in one ear,

out the other.

Christopher Robin, Pooh and Piglet

Stomping through the Hundred Acre Wood. (4–7)The capitalized phrase may refer to Some Versions of Pastoral, a literary

study by William Empson about the pastoral, a genre that treats of an idyllic

rustic life where city folk write poems as country folk, a possible reference

to the speaker’s situation.30 The inclusion of THE in the capitalized phrase

also allows for more general associations, the whistling of Beethoven’s Pastoral

Symphony, for example. However, the speaker may have intentionally

misquoted Empson’s title with an implicit dismissal of too academic a

treatment of a state better expressed by the humorous and charming image

of the speaker “stomping” through the wood along with Milne’s characters,

Christopher Robin, Pooh, and Piglet. Thus a seemingly straightforward

poem about a walk to the Zendo demonstrates not only the complexity of

everyday life as outer and inner worlds meet in the poet-practitioner, but

also suggests a critique.CONCLUSION: BACK TO BEGINNINGS AND COMMON THREADS

This brief survey suggests that Whalen’s body of work and poetics can be

understood as continuously evolving over time in relation to his evolving

Buddhist consciousness. Even his 1959 statement of poetics (that “poetry is

a picture or graph of a mind moving”) becomes modified in later years. In a

statement from 1987 entitled, “About Writing and Meditation,” he differentiates

between his two habits of meditation and writing: “In my experience

these two habits are at once mutually destructive and yet similar in kind.”31

In other words, poetry does not get written during meditation practice,

but from a state of mind which develops from meditation. The practice of

awareness is also one that does not make distinctions. In Zen terms this

might be considered big mind.32

In early poems it seems to be writing, not necessarily Buddhist practice

that can change consciousness and access the “Real self.” This may also be

because Whalen lacks formal Zen training in the 1950s and 1960s, when

most of his understanding of Zen comes either from books or from other

practitioners. His commitment is more to the Beat avant-garde impulse to

change American culture, evidenced partly by his intent to use a different

language with which to write poetry, one inflected with Zen Buddhist terminology

along with other levels and layers of discourse such as slang.

Eventually, as Whalen became a practitioner under the tutelage of

Richard Baker Roshi and the Zen poet-priest on whom he had perhaps

modeled himself from the 1950s, the focus of his later poems shifts to an

emphasis on practice having the power to change the self and others with

poetry understood more in Buddhist terms of skillful means. In “About

Writing and Meditation,” Whalen suggests a way that poetry and Zen connect:

“Maybe that’s where the poetry comes into all this, that it has to be an

articulation of my practice and an encouragement to you to enter into Buddhist

practice” (“AWM” 329).

Thus the purpose behind Whalen’s use of Zen changes as does the

emphasis on Zen in his poetry. There are fewer direct allusions to Zen

tenets, sutras, or practices and more attention to how phenomena of ordinary

life and mind interpenetrate. Burton Watson, a scholar of Chinese

and Japanese poetry, characterizes Zen poetry in a way that expresses the

essence of Whalen’s poetry project: “Zen poetry usually eschews specifically

religious or philosophical terminology in favor of everyday language,

seeking to express insight in terms of the imagery and verse forms current

in the secular culture of the period.”33

This shift is especially true in regard to how Whalen references kōans

in poems. Whalen comments on the kōan and poetry in an oblique way in

his 1991 interview with Schelling and Waldman when the question arises

of how meditation practice informs poetry. Whalen admits that although

poems or “certain phrases” don’t come to him in sitting meditation, “kōan

practice is an activity where you do repeat, where you do come back always

to a certain phrase,” hinting that he might include such phrases in poems

(“PW:ZI” 233). However, at this point in the interview Whalen abruptly

changes the subject, calling Schelling and Waldman’s questions about

poetry’s relation to meditation or kōan practice bogus. In keeping with this

attitude, although allusions to kōans continue to thread their way through

later poems, they are presented more subtly. “UPON THE POET’S PHOTOGRAPH,”

for example, the second section in “Epigrams and Imitations”

of 1981, recalls the earlier concern with original face:This printed face doesn’t see

A curious looking in;

Big map of nothing. (5–7)The first two lines of this haiku present the meeting of two faces with

the turn of the third line and the idea that both image and onlooker are

“nothing.”34 These three short lines more effectively question identity than

Whalen’s rhetorical questions of the 1950s.

This brief overview of Whalen’s poetry has shown that despite shifts in

his poetry from early to late, his basic concerns remain constant over time.

These can be understood as an interest in using Buddhist, especially Zen,

philosophy, psychology, and aesthetics, as the basis for his poetics and his

poems and a way to access the “Real self.” One such interest is his exploration

of the relation between what is inside the poet-speaker’s mind and what

is going on in the outside world. From this interface, the poem grows. The

poem is this interface. There is no distinction between the two. Whalen

addresses this issue explicitly in an interview with Leslie Scalapino as he

discusses how he puts his poems together, stating of “inside” and “outside”

that “it has some connection also with the way Buddhist psychology looks

at things; how you eventually find out the outside is really inside . . . You

can’t say there’s something out there. It’s all inside.”35 Thus, Whalen’s references

to Zen Buddhist tenets and practice in his poetry, first as poet, then

as poet-priest, is a constant throughout his writing career, and one when

used as a lens to look at his body of work, brings it all, momentarily, into

focus, a finger pointing at the moon.NOTES

1. Allen Ginsberg, “The Six Gallery Reading,” in Deliberate Prose, 240. Ginsberg’s

statement about this event, which brought East Coast Beats together with

West Coast Renaissance poets was originally made in 1957 and titled, “The Literary

Revolution in America.”

2. Definitions of Buddhist terms are from Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber, Franz-

Karl Ehrhard, and Michael S. Diener, The Shambhala Dictionary of Buddhism and

Zen, trans. Michael H. Kohn (Boston: Shambhala, 1991).

3. Unless otherwise stated, the early poetry of Whalen from the 1950s and

1960s is quoted from On Bear’s Head (New York: Harcourt, Brace, World, Inc.

and Coyote, 1969). Later poetry from the 1970s through the 1990s is quoted from

Canoeing Up Cabarga Creek (Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press, 1996). Hereafter these

books will be cited in the text respectively as OBH and CUCC. Sentient beings is a

Buddhist term. Whalen’s Greek term recalls Pound’s “New Paideuma,” described in

Culture. Borrowing the term from Frobenius, Pound uses it to refer to “‘New Learning’”

or “whatever men of my generation can offer our successors as means to the

new comprehension” (58). A letter from Whalen to Snyder of June 10, 1957, complains

of the way “kritics” have misrepresented the Beat Generation and states that

“the trouble is none of us has published anything like a manifesto.” He concludes

that whatever any of the group may write within the year “could present Slices of

the New Paideuma,” implying that this poem could be such a manifesto.

4. This letter is from the Ginsberg Papers, Courtesy of Department of Special

Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries. Note that

all of Whalen’s letters are quoted by permission of the Estate of Philip Whalen.

5. I am indebted to Gary Snyder for this characterization used in a letter to

Whalen of January 13, 1960, to describe Whalen’s concerns in “Self-Portrait from

Another Direction.” This letter is from Whalen’s archive at Reed College.

6. Philip Whalen, “Interview with Lee Bartlett,” in Off the Wall, 71.

7. In her study of the kōan with Miura Isshu, Ruth Fuller Sasaki explains that

the Japanese student must find the appropriate “‘capping phrase’” for the kōan

assigned; then he presents “it to his teacher as the final step in his study of the

kōan” (Zen Kōan 80). These phrases are usually drawn from the Zen anthology,

Zenrinkushu.

8. Philip Whalen, “Statement of Poetics,” New American Poetry Anthology,

ed. Donald Allen (New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1960): 420. Note that this statement

first appears titled, “Since You Ask Me,” as the conclusion to Memoirs of an

Interglacial Age and was created as a press release for a reading tour Whalen and

Michael McClure went on in 1959.

9. Heinrich Dumoulin explains this image as a net of pearls hanging over

Indra’s palace, whereby “each reflects the others . . . in looking at one pearl one

sees them all” (47).

10. Both Blyth and Suzuki make connections between Zen and poetry,

Blyth especially connecting Zen and haiku. In Suzuki’s series of essays on Zen

Buddhism, he not only alludes to haiku, but frequently quotes the verses of Zen

figures and Chinese and Japanese poets, their poems demonstrating enlightenment

experiences and moments of awareness. Suzuki also discusses Zen’s claims

regarding the limitations of more discursive and rational language. Whalen would

also have been familiar with Snyder’s translations of the poems of Ch’an hermit

poet, Han Shan.

11. Albert Saijo had studied Zen with Nyogen Senzaki in Los Angeles. For

more on this period see interviews with Whalen collected in Off the Wall. For

more on Snyder’s introduction to Zen see Suiter’s Poets on the Peaks. The Marin

County zendo was organized by Gary Snyder.

12. Philip Whalen, “Philip Whalen: Zen Interview,” in Disembodied Poetics,

225. Hereafter quotes from this interview will be cited in the text with the abbreviation,

“PW:ZI.”

13. Note that all letters from Whalen to Snyder are quoted permission of

Snyder’s archive at the University of California, Davis, Davis, California and by

permission of the estate of Philip Whalen.

14. See Thurley for Buddhism as passive; see Davidson for a more positive

presentation of Buddhism and Whalen’s work.

15. D.T. Suzuki, Essays in Zen Buddhism, 3rd series glosses this: “The idea

is to show immediateness of action, an uninterrupted movement of life-energy”

(363).

16. D.T. Suzuki, Manual of Zen Buddhism provides the Sanskrit and its translation:

“Gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi svaha,”or in English: “O Bodhi, gone

gone gone to the other shore, landed at the other shore, Svaha!” (27).

17. Lawrence Lipton, 316.

18. D.T. Suzuki, Essays in Zen Buddhism, 3rd series, 238.

19. Philip Whalen interview with the author, San Francisco, California, July

2000. On his use of haiku, Whalen noted the difficulty of writing haiku in English,

stating that the Japanese language was needed for true haiku. “The Slop Barrel”

also ends with a haiku-like stanza as do other poems from this period.

20. R.H. Blyth, Haiku, Vol 1, 24 and D.T. Suzuki, Zen and Japanese Culture

225. At times Whalen uses a series of shorter haiku-like stanzas to make longer

poems, “Opening the Mountain, Tamalpais: 22:x:65,” 1965, being an example.

This poem, a record of the circumambulation of Mt. Tam by Whalen, Snyder, and

Ginsberg, is made up of short sections in which natural images are juxtaposed

with moments of realization, memories, or quotes from the day usually with a turn

before the last line in haiku-like fashion.

21. According to the interview with the author in summer, 2000, Whalen was

familiar with the collection of kōan compiled by Paul Reps and Nyogen Senzaki,

Zen Flesh, Zen Bones; this kōan appears on pages 143–144 of this volume. The title

of this poem as it originally appeared in Memoirs of an Interglacial Age did not reference

the 29th kōan, whereas the title thereafter does. Leaving out this information

makes the poem more problematic, forcing readers to make the connection

themselves. “All About Art and Life,” another poem of this period, asks kōan-like

questions, too: “WHAT IS IT I’M SEEING?” and “WHO’S LOOKING?”

22. According to Alan Watts in The Way of Zen, the usual first kōans given

to students are Hui-Neng’s “Original Face,” Chao-Chou’s “Wu,” or Hakuin’s “One

Hand” (161).

23. Both sutras are important texts for Zen Buddhists. Whalen expresses his

own understanding of the Lankavatara Sutra to Ginsberg in a letter of September

11, 1958, stating that this sutra “explains how the mind is constituted & how it manufactures

illusion.” This sutra also addresses the problems with language familiar to

practitioners of Zen, that words are not the truth but only able to point to it.

24. Philip Whalen, “Philip Whalen,” in San Francisco Beat, ed. David Meltzer,

329.

25. This is Basō’s kōan, “Sun-faced Buddhas, Moon-faced Buddhas.” Suzuki

Roshi not only established San Francisco Zen Center, but also gave Whalen’s

teacher, Richard Baker Roshi, dharma transmission.

26. Regarding his poetic output and its publication, Enough Said, 1980, was his

last major original collection, aside from Some of These Days, 1999. The title of the

1980 volume may be Whalen’s self-criticism on the writing of poetry from a Zen

Perspective. Thanks to Michael Rothenberg for a discussion of this idea. Regarding

Whalen as teacher, the didactic role has been a congenial one for him and part of his

poetic agenda from the 1950s as evidenced in “Since You Ask Me,” where he claims

that he has inherited Dr. Johnson’s title of teacher.

27. Whalen’s translations appear in two out of three of the Dōgen volumes

(Moon in a Dewdrop and Enlightenment Unfolds) while the third volume, Beyond

Thinking, is dedicated to him. San Francisco Zen Center under the direction of Richard

Baker Roshi was the original sponsor of Tanahasi’s project beginning in 1977.

28. For more on this period, see the Preface to this volume.

29. Richard Baker Roshi resigned as head of San Francisco Zen Center in

1983 over a scandal that began with exposure of his sexual indiscretions and was

later compounded by what some considered his authoritarian leadership style.

Whalen, loyal to his teacher, followed Baker Roshi to the new Zen center he

established in New Mexico, spending several years there. Whalen subsequently

received dharma transmission from Baker Roshi. For more on this period see

Downing’s Shoes Outside the Door.

30. Thanks to Eric Birdsall for an enlightening discussion of William Empson

and this poem.

31. Philip Whalen, “About Writing and Meditation,” in Beneath a Single

Moon, ed. Kent Johnson and Craig Paulenich, 328. Hereafter quotes from

this statement will be cited in the text using the abbreviation, “AWM.” This

statement was originally made at a conference entitled, “The Poetics of Emptiness,”

at Green Gulch Farm in April 1987 and was reprinted in Beneath a Single

Moon.

32. “Big mind” is a term used by the Soto Zen teacher and founder of the San

Francisco Zen Center Shunryu Suzuki in his talks collected in the volume, Zen

Mind, Beginner’s Mind. Of big mind he states that it is “something to express, but

it is not something to figure out. Big mind is something you have, not something

to seek for” (92). In another lecture he explains that the essence of mind is “that

everything is included within your mind” (35).

33. Burton Watson, “Zen Poetry,” in Zen: Tradition and Transition, ed. Kenneth

Kraft, 106.

34. In an unpublished typescript, “Notions About Teaching Classes Dealing

With The Zen Lineage,” in Whalen’s archive at UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, he

comments that kōans and stories in kōan books had “one kind of meaning” before

“intensive zazen” and “another meaning” after practicing at Zen Center. He concludes

that book learning needs to be “measured against one’s own experience and

judgment” (7–8). This is quoted by permission of the Bancroft Library and the

Estate of Philip Whalen.

35. Leslie Scalapino, “How Phenomena Appear to Unfold.” This is a quote

from an interview Leslie Scalapino had with Whalen in the 1980s included in a

talk with this title given at Naropa in 1989.

WORKS CITEDBlyth, R.H. Haiku. Vol. 1. Tokyo: The Hokuseido Press, 1981.

Davidson, Michael. The San Francisco Renaissance. Cambridge and New York:

Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Downing, Michael. Shoes Outside the Door. Washington DC: Counterpoint, 2001.

Dumoulin, Heinrich. Zen Buddhism: A History. Vol. l. Trans. James W. Heisig and

Paul Knitter. New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan, 1994.

Fischer-Schreiber, Ingrid, Franz-Karl Ehrhard, and Michael S. Diener. The

Shambhala Dictionary of Buddhism and Zen. Translated by Michael H. Kohn.

Boston: Shambhala, 1991.

Ginsberg, Allen. “The Six Gallery Reading.” Deliberate Prose. Ed. Bill Morgan.

New York: HarperCollins, 2000. 239–242.

Lipton, Lawrence. The Holy Barbarians. New York: Julian Messner, Inc., 1959.

Miura, Isshu and Ruth Fuller Sasaki. The Zen Kōan: Its History and Use in Rinzai

Zen. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1965.

Pound, Ezra. Culture. Norfolk, CT: New Directions, 1938.

Reps, Paul and Nyogen Senzaki. Compilers. Zen Flesh, Zen Bones. Boston and

Rutland, VT: Tuttle Publishing, 1957.

Scalapino, Leslie. How Phenomena Appear to Unfold. Elmwood, CT: Potes & Poets

Press, Inc., 1990.

Shaw, R.D.M. Trans. and ed. The Blue Cliff Records. London: Michael Joseph Ltd.,

1961.

Shunryu, Suzuki. Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. New York: Weatherhill, 1994.

Snyder, Gary. Letter to Philip Whalen. 13 January 1960. Philip Whalen Papers,

Special Collections, Eric V. Hauser Memorial Library, Reed College, Portland,

Oregon and courtesy of Gary Snyder.

Suiter, John. Poets on the Peaks. Washington, DC: Counterpoint, 2002.

Suzuki, D.T. Essays in Zen Buddhism. 1st Series. 1949. New York: Grove Press,

Inc., 1961.

--. Essays in Zen Buddhism. 3rd Series. 1953. New York: Samuel Weiser Inc.,

1976.

--. Manual of Zen Buddhism. 1935. New York: Grove Press, 1960.

--. Zen and Japanese Culture. 1938. Reprint. New York: Bollingen Foundation,

Inc., 1959.

Thurley, Geoffrey. “The Development of the New Language: Michael McClure,

Philip Whalen, and Gregory Corso.” The Beats: Essays in Criticism. Ed. Lee

Bartlett. Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland, 1981. 165–180.

Watson, Burton. “Zen Poetry.” Zen: Tradition and Transition. Ed. Kenneth Kraft.

New York: Grove Press, 1988. 105–124.

Watts, Alan. The Way of Zen. New York: Pantheon Books, Inc., 1957.

122 Jane Falk

Whalen, Philip. “About Writing and Meditation.” Beneath a Single Moon. Edited

by Kent Johnson and Craig Paulenich. Boston: Shambhala Publications, Inc.,

1991. 328–331.

--. Canoeing Up Cabarga Creek. Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press, 1996.

--. Letter to Allen Ginsberg. 11 September 1958. Ginsberg Papers. Courtesy

of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries.

--. Letter to Allen Ginsberg. 26 July 1960. Ginsberg Papers. Courtesy of

Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University

Libraries.

--. Letter to Gary Snyder. 7 August 1954. Gary Snyder Papers, Department

of Special Collections, University of California Library, Davis, California

and courtesy of the Estate of Philip Whalen.

--. Letter to Gary Snyder. 10 June 1957. Gary Snyder Papers, Department of

Special Collections, University of California Library, Davis, California and

courtesy of the Estate of Philip Whalen.

--. Memoirs of an Interglacial Age. San Francisco, CA: The Auerhahn Press,

1960.

. “Notions About Teaching Classes Dealing with the Zen Lineage.”

Unpublished typescript, Philip Whalen Papers, the Bancroft Library, University

of California, Berkeley and courtesy of the Estate of Philip Whalen.

--. Off the Wall. Ed. Donald Allen. Bolinas, CA: Four Seasons Foundation,

1978.

--. On Bear’s Head. New York: Harcourt, Brace, World, Inc. and Coyote,

1969.

--. “Philip Whalen.” Interview with David Meltzer. San Francisco Beat. Ed.

David Meltzer. San Francisco, CA: City Lights Books, 2001. 325–351.

--. “Philip Whalen: Zen Interview.” Interview with Andrew Schelling and

Anne Waldman. Disembodied Poetics. Eds. Anne Waldman and Andrew

Schelling. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1994. 224–237.

--. “Statements on Poetics.” The New American Poetry: 1945–1960. Edited

by Donald Allen. New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1960. 42