ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

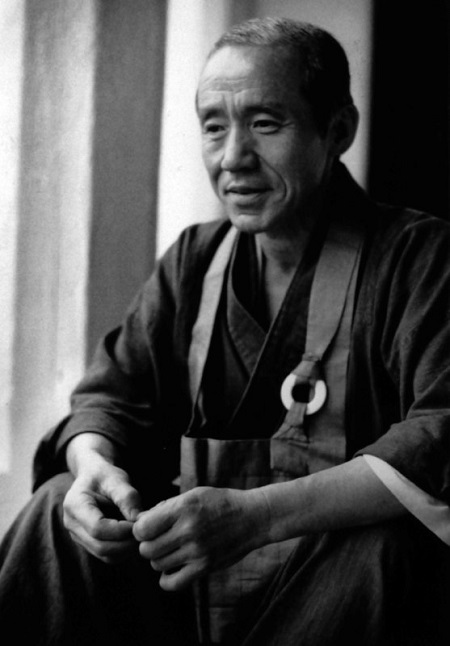

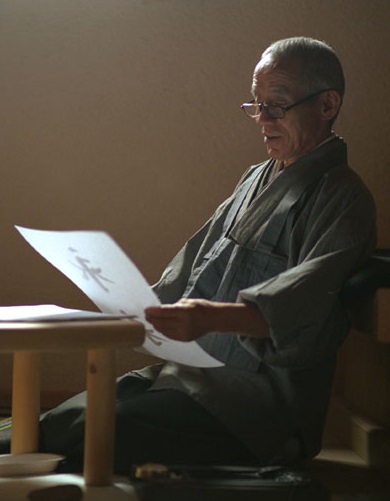

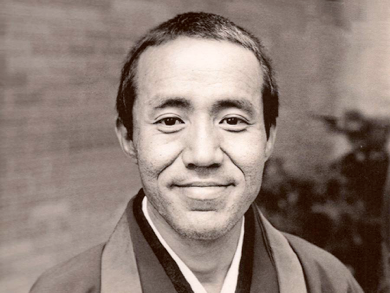

乙川弘文 Otogawa Kōbun (1938-2002)

乙川知野 Otogawa Chino, 法雲弘文 Hōun Kōbun,

Kobun Chino Otogawa

Biography

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kobun_Chino_Otogawa

http://www.kobun-sama.org/english/biografie.htm

Kobun was born on February 1, 1938 in the small town of Kamo, Niigata Prefecture, in northwestern Japan, to a family from a long line of Soto Zen priests. The youngest of six children, he spent his childhood at the family temple, Jokoji. When he was eight years old his father died of cancer. It was

during a time when Japan had been devastated by the Second World War, and there were continuing food shortages. His mother somehow fed her family, sometimes cooking stems of pumpkin when the pumpkins were gone, and using plants foraged in the woods. Ordained at age thirteen, Kobun was adoopted at fourteen by Hozan Koei Chino, Roshi, whose temple, Kotaiji, was about a mile from Kobun's family temple. Chino Roshi, without heirs, trained Kobun so that, in the Japanese tradition, Kobun would inherit the abbacy of Kotaiji. Chino Roshi had a deep, resonant voice, and chanting, not zazen, was his main

practice. Kobun's training often took place as he followed his teacher through the fields as they walked to households in need of their ceremonies and prayers, chanting as they went. He received Dharma transmission from Koei Chino Roshi in Kamo in l962.

Kobun attended Komazawa University from 1957 to 1961 in Kyoto. From there he went on to Kyoto University from 1961 to 1965 for a degree in Mahayana Buddhism, where his masters thesis subject was a study of Mahayanasmgraha. In part he chose to study in Kyoto to be close to Kodo Sawaki Roshi, with whom he had sat sesshin since high school days. Sawaki Roshi strongly advocated revitalization of zazen

as the central practice of Soto Zen, a subject of particular interest to Kobun. During his years in Kyoto Kobun also trained in Kyudo with the archery master, Kanjuro Shibata Sensei. Also, from an early age, he was an intuitive and skilled calligrapher.

After university Kobun trained at Eiheiji monastery, for three years from 1965-1967. Toward the end of this time, he was asked to train incoming novices. He broke tradition by getting permission to put aside the kyosaku, the practice stick which had sometimes been misused as a tool for cruelly hazing young monks.

In 1967, while at Eiheiji, Kobun received a letter from Suzuki Roshi, who had been teaching in San Francisco since 1958, where he founded the San Francisco Zen Center. The letter was an invitation for Kobun to come to California to help establish Tassjara, the first Zen monastery in America. Kobun later said this was a dream come true for him. But when he asked his master's permission, Chino Roshi three times said "No." Ignoring ancient tradition, which required him to accept a third denial, Kobun took ship for San Francisco. This was 1967. He brought gifts from Eiheiji for the new monastery: A huge drum, a bell, and a mokugyo. (In the Tassajara fire of 1978 these gifts were destroyed. All that was left of the bell was a puddle of bronze.) He contributed many of the forms still in use today at Tassajara and San Francisco Zen Center, among them the sounding of the han, the drum, the bells, and the taking of meals in formal oryoki style. He was a resident priest at Tassajara until 1969. "I don't think people realize how important he was in establishing Tassajara Zen Center," says Bob Watkins, who studied with Kobun for thirty-five years. "There were only a handful of us there at the time, sitting on army blankets in the old building we used as a zendo. "In the beginning Kobun taught us everything: How to put the zendo together, breathing, posture, how to do oryoki meals in Navy surplus bowls."

Haiku Zendo, a suburban offshoot of San Francisco Zen Center, was created in Los Altos, California, in 1966. Suzuki Roshi, and later Katagiri Roshi, traveled the 30 miles from San Francisco to lecture and teach there. In 1967 this sangha raised the funds for Kobun's journey to America, with the idea that he would become their resident teacher. Suzuki Roshi, however, first needed Kobun at Tassajara, so it wasn't until 1970 that Kobun became the resident teacher at Haiku Zendo. This small zendo was a remodeled garage with seventeen seats. Located at the home of Marion Derby, who later moved to Tassajara, it was then purchased and maintained by Les Kaye and his family. Kobun and his new wife Harriet soon moved into a house one block away. The interior of the zendo had an authentic, Japanese feeling, having been constructed with carefully chosen materials and designed with a raised sitting platform. It was eventually too small for the sangha which grew rapidly under Kobun's guidance.

His style was informal. He preferred to be called Kobun, not "Sensei," and never "Roshi," and he encouraged his students to think of him as their friend rather than their master. His unpredictable and subtle style resonated with the times as he emphasized life-in-the-world, encouraging his students to marry and have children. During those early days he was almost always available to his students, night and day, even after his two children were born, Taido in October, 1971, Yoshiko in May, 1973.

Kobun gave workshops and courses through Stanford University, Foothill College, and U. C. Santa Cruz. The course Kobun taught at Stanford, offered through an extended education program open to the entire community, was called The Roots of Zen, and focused on Indian Madhyamika and Yogachara philosopies. He was also, after Suzuki Roshi's death in 1971, on call to San Francisco Zen Center, helping Baker Roshi with teaching the forms of Zen, including instructions for ceremonies, translations of chants and sutras, funerals, and ordinations. Kobun also did the calligraphy on Zen Center rakusus and on stupas marking ashes burial sites.

During this time, too, Kobun became a close personal friend of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, who had made a pact with Suzuki Roshi to establish a Buddhist university in the United States. After Suzuki Roshi passed away, Trungpa Rinpoche asked for Kobun's help in establishing his vision in Colorado. He needed Kobun to help instruct his students in zazen, drumming, bowing, oryoki, and calligraphy. Kobun introduced Rinpoche to Shibata Sensei, and that relationship became the source of kyudo practice in the Shambala tradition, still led by Shibata Sensei today. Kobun taught at the inaugural summer sesshion of Naropa in 1974 and returned to what is now Shambala Mountain Center and Naropa University every year to teach and lead sesshins.

The Santa Cruz Zen Center was founded in 1971 by Kobun and local students, with Jim Goodhue as the first director. Kobun led sitting practice and lectured every week in Santa Cruz for over ten years. He also helped found Spring Mountain in Mendocino County north of San Francisco in the early 1970s. A small residential community, it underwent several transformations in the Ukiah area, until practice there came to an end in the 1980's.

Trout Black, Stephan Bodian, Buff Bradley, Elmer Caruso (who headed the Spring Mountain effort), Jerry Halpern, and Phil Olsen were among the first monks ordained by Kobun, in the early 1970s. Four seven-day sesshins a year and many weekend and one day sittings were held in a youth hostel a few miles from Haiku zendo on the Duveneck ranch, Hidden Villa, in Los Altos Hills. After a few years of hauling cushions, food, mats, tan and pots back and forth, the sangha decided to look for a permanent place to practice. The sangha was incorporated in the State of California as Bodhi. At Kobun's suggestion, it was stated in the bylaws that all beings are members of this sangha. Funds were raised while several practice sites were being considered. Eventually the sangha decided to buy both an urban city property and one in the Santa Cruz mountains. The city center, Kannon-do, was established in Mountain View with Keido Les Kaye as chief priest, who was recognized in 1986 as a Zen teacher and dharma heir in the lineage of Shunryu Suzuki.

Kobun named the site in the mountains Jikoji, meaning Compassion Light Temple. His elder brother, Keibun, abbot of the family temple in Japan, came to America to inaugurate the new temple with a Dai Segaki, a Hungry Ghost Ceremony, in 1982.

Kobun and his wife, Harriet, separated in the late 1970's and finally divorced in the 1980's. Kobun helpled Harriet move with the children to Little Rock, Arkansas where she had family roots and could continue her graduate education in nursing. Missing them greatly, he wanted to be within at least one day's driving distance of his children. Taos, New Mexico, in the American Southwest, met the requirement, so he settled there, and his children visited him on school vacations. At that time, Kobun's student, Bob Watkins, was looking for land on which to create a small monastery. A property was found under the brow of El Salto mountain, at an elevation of 8,000 feet, in the Sangre de Christo mountains near Taos. It included a small adobe house and a garage that could be converted into a small zendo. Kobun named it Hokoji, founded in 1983. He translated the name as Phoenix Light Temple. Hokoji can also be translated as Wisdom Light Temple. For the past 10 years, Stanley White has been holding the position of Osho or head priest. Here, Zazen pratice on a daily basis and regular sesshins have been going on for over 25 years by now. In 1984 Kobun himself bought a piece of property down the road from the zendo, and began to build a house in the forest, a coiling dragon of embedded colored stones encircling its foundation. Meanwhile he rented a house in Taos, which he named Saiho-in, after the dharma name of his close friend and companion, Stephanie Sirgo. Kobun returned often from Taos to California to lead sesshins at Jikoji.

Kobun began to be known as a traveling teacher as he divided his time among Jikoji, Hokoji, and Shambala sanghas in the United States. Late in the 1980s he began visiting Europe to help friend and former student from Tassajara, Vanja Palmers, who was leading groups of Zen students in Austria, Germany and Switzerland. Over the course of 15 years, Kobun helped Vanja lead sesshins and they taught and ordained many students together. With his help and encouragement, Vanja and his European Zen friends established several new centers, particularly Felsentor and Puregg. In 1991 Vanja received Dharma Transmission from Kobun. During this time Kobun also met his future wife, Katrin, at Puregg.

Because Kobun's former master, Chino Roshi, had realized that Kobun would never return to Kotaiji, Chinos temple in Japan, he formally separated from Kobun. Kobun was then re-adopted into the Otogawa lineage and took his original family name. Consequently his first two children have the surname Chino, while his second family has the name Otogawa. In the 1990s, long since reconciled with his master, Kobun met the monk whom Chino Roshi had adopted to inherit the temple in his place. He said, "Now I have a little Dharma brother in Japan who is taking care of my master. It feels very good... Togo is his name. Togo means satori."

Kobun and Katrin moved to Santa Cruz in the 1990's where they lived with their three children, Maya, Tatsuko, and Alyosha in a home Kobun named Raigho-in. It was a centuries-old style Japanese farmhouse newly built and owned by Ken Wing and Hollis DeLancy. They had helped support Jikoji and Kobun for many years, and had hosted him on trips to Japan, India, and elsewhere.

After his divorce from Harriet, Kobun, while he continued to sit zazen with his students, considered himself in retreat from formal teaching. But after the birth of Alyosha, his third child with Katrin, he came out of retreat to teach again. This motivated a move to Colorado, where he was offered a position on the Naropa faculty. The family lived at Shambala and Kobun commuted to his classes at Naropa. In 2000 he was appointed to the World Wisdom Chair.

Martin Mosko, a landscape architect and garden designer based in Boulder was a long time student and friend of Kobun. Martin also trained with Kobun's brother, Hojosama Keibun Otogawa, abbot of the family

temple, and received dharma transmission from him. In 2001 Kobun consecrated a Zen center and garden Martin had created as Hakubai Temple. Martin Hakubai Mosko was installed as abbot in a Mountain Seat Ceremony in the Spring of 2004.

By 2000, Kobun had given the precepts to over one hundred students. Most of the ceremonies were Zuike Tokudo, or lay ordination. Several were Shukke Tokudo, or novice priest ordinations.

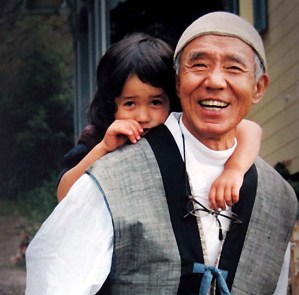

Kobun Chino, Roshi (1938-2002) with his daughter Maya.

Kobun Chino, Roshi (1938-2002) with his daughter Maya.

On July 26, 2002, Kobun drowned in Vanja’s swimming pond in Switzerland while trying to rescue his five-year-old daughter Maya, who also drowned. Following Kobun's death, Vanja Palmers, as his most senior heir, completed transmission for Angie Boissevain, Caroline Atkinson, Jean Leyshon, Bob Watkins, and later, Michael Newhall, the current Resident Teacher at Jikoji. He also transmitted the dharma to Ian Forsberg in Taos. Angie Boissevain had served as Director of Jikoji under Kobun for almost two decades, and began teaching with his encouragement. She now leads the Floating Zendo in San Jose. Carolyn Atkinson founded and leads the Everyday Dharma Zen Center in Santa Cruz. Both Ian and Jean are active at Hokoji, each leading at least one yearly sesshin, and also traveling to lead sesshins at other centers.

Jerry Halpern, wrote, "Possibly Kobun's finest quality as a teacher was that he required his students to live their own lives, and he encouraged them to become free to do so."

Autobiography

This 'autobiography' is a work of love and dedication by Angie Boissevain. Over the years, she taped and transcribed many talks Kobun gave and now, upon request and especially for this web-site, she searched for passages where he talks about himself and put together this fascinationg patchwork 'autobiography'.

When I think, “Why am I here?” it’s really unthinkable to find a reason why. It feels like being pushed by some force to keep up my presence, no matter where it is. Pushed from the past, that is one feeling. Another is always a powerful longing which comes up from inside me, with a wish to create something which I would be able to do. For this reason, my second elder brother definitely named me Dreamer. “My youngest brother is a big dreamer,” he says. Maybe so. He is sort of a realistic realist, like the second son of Karamazov brother. Incredibly intellectual and cynical and humorous. He can chop up everything he wants to. And yet, everyone calls him a holy man, or a saint. His nickname has been “Stainless,” or “Saint.” Saint Keibun is his nickname from Junior High School. He keeps up all relationships; from the time he was a very small child he has kept proper communication. When someone writes a letter, within one day he writes back, which is a miracle to me. I never write back! And every time he lectures me, “See, you are the Dreamer. I am the Saint,” he says.

I am unable to define myself, what I actually am. A lot of new things happen every day, it amazes me how many new things come in new days. On the other hand, how strange it is, old things always follow right to the new days, all of them.

My father passed away at the age of sixty three. I was about seven years old. I still have memories that he took me to ofuro (baths) and tap my hips and pull my something and say, “Grow big!” I even hear his voice. When I was about three and a half years old, his three boys got instruction on how to sit. It was a summer evening. Many fireflies were appearing from the temple’s lotus pond. We were enjoying the wide temple corridor, cooling ourselves. Then big bother, middle brother and littlest one, myself, all faced the garden and start to sit, and father came around to correct our posture.

I remember, that same night we saw ...it went “Shuuu...: Northern lights? No, no, we say spirit of the dead. We figured later that it was an owl carrying sulfur fire around his body. The temple has a burial ground, and on warm summer nights, once in a while the sulfur of the buried starts to burn in the heat. We thought it was a holy ghost flying around.

I wasn’t taught what shikan taza is, I haven’t had formal koan training. From childhood, whatever I was interested in, I could study, so I started with biology, and all kinds of necessary things, as usual with children in Japan. Calligraphy. Japanese language, to speak, write, think, which relates with the very symbolic form of nature and things. By seeing each character, you can reproduce each thing in nature. I was very involved in learning language in elementary school. My name, given to me by my natural father, was a big problem to me. All family members had “bun” in their name. Father’s name was Bunryu. Bun means question mark. And ryu is dragon...

It’s also a question to me what kind of animal this ryu is..So, my father is, to me, a very big question. His master, who adopted my father when he was six years old, gave him this name. So, his, grandmaster’s name is Bunzan. Bun is another question. Eldest brother was given the same name as father’s adoptive father, so the grandfather’s name came to the eldest brother, but the sound is Bunzo. It’s the same character, but we get confused, the pronunciation was different. The same character: Bunzo, which sounds like: three. That is still a big question, number three.

Second brother was Keibun. Kei is “respect,” which he pronounced himself, he was very proud. “Everyone respects me!” And he said, “This little one, everyone loves him, but everyone respects me.” ...It is supposed to be that he respect everybody, that is why the name was given to him. I wish he was here. Third one, this one, is called Kobun. Forgotten! I have never worn new clothes because everyone’s clothes ended up on me. Even now my elder brother’s and my natural father’s clothes fit me. Very strange. Ko is structured from the archery bow, which coincidentally, I picked as my exercise when I was in Kyoto. That part I understand now, why my father gave this part of my name, ko. The other side is “mu.” Mu is like the koan Muji, a very big subject. It means :”nothing”. Especially for American students, mu is a very hard concept to experience, and is still, for me, a big question, because I haven’t been checked by great Zen master about the koan Muji! Some day I want to figure it out!

One day a very vigorous man asked me, among many people, making me very embarrassed, “I heard you are a Zen master. Have you ever experienced great enlightenment?” I was so embarrassed! I had to say, “No! I haven’t experienced such crunchy stuff!”

For some reason this name of my whole family has been a very big question. Until recently, I didn’t pay much attention to where it came from and who gave this kind of name generation after generation. I found out that it is a name picked up from Manjusri. And Bunzan is also in a koan. Manjusri’s koan, which you probably know , about the three places Manjusri stayed in outside of Shakyamuni Buddha’s training period. Mahakashyapa was very upset because he was the head practicer and as soon as the training period started, Manjusri Bodhisattva disappeared from the congregation and no one knew where he went. On the last day of the practice period, Manjusri came back and Mahakashyapa was very mad at him. “It’s against the rule of the monastery!” He asked Shakyamuni Buddha for a discussion and was ready to hit the gong to gather everybody in a special court. But as he lifted his knocker, he had strange visions of very very sincere practicers as Manjusri’s activity for the three months, like a movie. In Mahakashyapa’s vision, Manjusri was, during one month, staying with many children, like a nursery school. Another month he was staying in a place like San Francisco downtown, like a topless bar, or massage parlor, or something like that. Another month, he was drifting around doing whatever he wanted to do. Mahakashyapa was so astounded by this scene that he quit his proposed discussion.

I was thirteen years old. I said, “I will keep, sustain, ‘No Killing Life.’ Fu sessho kai. I didn’t know what I was saying, but my ordination master was sitting way up, like a seat about same height as Buddha’s seat. I was sitting there surrounded by shaved monks and nuns, trying not to run away! They were sitting there in zazen, so I grabbed their energy, and in my high-pitched voice said, “I will.” Thirteen. Forty years later, I appreciate that that happened. I didn’t appreciate it at that time. Feeling was alright, although the next day the village boys came as usual. “Shall we go?” “Yes, let’s go.” And we were off on bicycles, with fishing tackle and lunch box. At two or three o’clock we started for the irrigation ditch in a rice field. Some ditches were very big, like a little river. You get in the reeds and fish and come back with tons of fish. The day before I had been saying “I will not kill life!”

Among various studies I have experienced in my life, I feel very appreciative to have received the Precepts. The older I become, the more I appreciate them. I was very lucky, being born as a child of a Zen priest . And growing up in the atmosphere of temple life...again, deep appreciation. At the same time, I feel that if I were born in a different family, where would I be?

When I went back to Japan, I saw a neighbor who has also about the same amount of white hair, and we looked at our heads and said, “My goodness, you have become very old!” We talked about how bad we were in elementary school, with the sort of rhythm and texture of mind that is the very same as before...This man is always famous as the bad boy in the town, and I loved to be with this bad man. No one understood me. “How can he go with this violent man?” The only thing he couldn’t stand was electric shock. I grasped that weak point in him and always mentioned it. “Don’t talk about it!”Everyone was frightened of this man. One day we went to swim in a mountain stream, and he was drowning, and I saved his life, and we promised not to talk about it. It was that kind of relationship. He asked me, “Are there beautiful people in America?” I said, “Yes.” He was so curious about you...

I was born as a child of a priest. Without giving birth to a monk’s mind, I was already caught, and shaved my head! And, like children studying the Suzuki method of violin, in an unconscious state I already memorized so many sutras! Without knowing the meaning of any of it...My whole life has been protesting the monkhood! I still cannot get out of the pickle jar!

I lost my natural father when I was eight, but to me he has never died. I remember his smooth, silk-like cold feet. That’s all, the last image of father. Long, very long toe nails, toes, and round tips, I remember. Huge. My hand was about that big. Eight years old, very small hand. His feet were huge!

After someone has died you have this feeling that there is no body any more, but there is still the force of that person being there and catching up to our life, letting us notice that their life is still going on. An example is my father. Today I again thought of my father . The recent occasion which particularly happened this year was originated--appeared in phenomena-- by my father. I was so surprised! He passed away the year the Second World War was over, but it still reminds me that his influence is on people. It’s very surprising, all those people who were with my father still remember what he wished to see now. It’s very interesting. It’s the same for people who passed away in this country since I came here.

My experience about love, expression of love, was this year’s biggest present to me, my elder brother’s visit. He is so tricky! I cannot believe it! The purpose of his visit to this country...no one knows! To me, it’s simply that he wants to be a very demanding elder brother, showing what elder brother means to me. It’s a fantastic visit to me. We didn’t meet for very long, only probably three hours. He spent five minutes praising my effort, and two hours and fifty five minutes lecturing. Lecturing continuously, and always saying, “This is my last advice!” and then went on and on! And he said, “It’s not me speaking, it’s your father speaking through me!” I was very happy that he could meet many of you. But he said, “I am going to come to visit you every year!” Immediately, I got a headache! He can come, but I’ll go to sesshin!

I don’t remember the exact day and time, but my professor in Kyoto University, Keiji Nishitani, through his lectures and seminars I studied about your past. Western philosophies, religions. A very excellent teacher, he’s almost eighty years now...About seventeen years ago I was his student. One of the papers I wrote was “God concept of Modern Man.” I get all sweaty when I remember my discussion about it. He said, “Your report was excellent!”

I was interested in carving out the historical Buddha’s life. I wanted to know what kind of life he lived, so my study was focussed toward historical material, so I ended up in Kyoto University where the best library is. In its many stories, and in the basement, I was like a bookworm crawling there. I’m still not clear what kind of person Gautama Buddha was. To think about him makes me feel I immediately go back home where I started. I was very proud of what I studied, too proud, I think.

My young mind drove me to find out what was Buddha’s enlightenment. Most of my early years were spent only on this point, which drove me to various places. Years and years of practice with doubt, with thirst for knowledge. Forgetting reality, my face turned around, and I went way into the past. So you can imagine how far I lost myself. Head was first, so that my head went into the books and traveled in books. All kinds of Buddhist literature. I feel now it was a nightmare! At that time I was so excited...my body was like this (hunched, headfirst), and I didn’t understand anything! I became a very big, smart ass-hole. And I reached the point of the theory of the very close process of the enlightened state of practice--how that knowledge turns to shiny wisdom. It was very very hard. Oh, certainly I was completely head-oriented.

My two teachers, Soko Eto [?}, the professor, and Kodo Sawaki Roshi, were enshrined in Kosho Uchiyama Roshi’s temple, Antaiji. I brought incense and flowers every month for four years, and whenever Kosho Uchiyama Roshi saw my face in his temple, he would say, “Oh, hi, Kobun-san. O-cha, dozo!” “How about a cup of tea?” And he would say, “Quit school and come here and sit with us.” Every time. And for some reason, I didn’t quite feel comfortable about joining. I was Kodo Sawaki Roshi’s very young student, from high school time, so it was very very hard, and I stayed as a bookie type, and every month went back.

And then Gajin Nagao, my professor, at the end of my Master’s thesis, said, “Don’t you want to stay here and continue to study?” I was very much suffering at that time, in various ways. Completely confused! And I had reached the point of understanding that after endless practice, the vows are accomplished in concrete form as a Bodhisattva for many lifetimes, still, endlessly Bodhisattva’s practice continues. In my sight at that time, everybody’s face looked like Bodhisattva except my own. So I begged Professor Nagao, “Please, let me go to the monastery. I need to sit again!”

I recall my first impression of Eiheiji. I wasn’t entering Eiheiji as a monk then. Before that, I went to visit the temple. The monks’ practice quarters were hidden from the pilgrims, from tourists and sightseers, and yet, in the evening, in the gold light of sunset, about seventy monks carrying oryoki, were traveling from the monks’ hall to the kitchen through the long corridor passing through the Buddha Hall. All carried oryoki with both hands, like this, and their heads were shaved, and they wore the same kind of robes. Every one of them was kind of transparent, their skin whiteish and their eyes not moving, looking at the floor as they went. Like looking at ganko, wild geese, flying together. “Oh, my goodness! I have never seen such a thing in my life. I’ve got to come here!” And I went back to Kyoto to continue to study. This ganko, monks’ work, was very impressive to me. “What’s in their mind?” I knew what it was. But, “What’s in their mind?” I thought there must be some big thing going on with them. Then I went to my Dharma master, who had watched me from birth to adulthood, and told him, I am going to stop school and go to a monastery. Please let me go to head monastery where the spirit of Dogen Zenji must still be alive. I want to experience actual practice day and night. If I continue to study in academic field of Buddhist literature, my brain might burst into pieces. Too much already, please let me go to the monastery.

I was not just getting fed up with study, there was my youth demanding that I must do something more urgent than just intellectual study. At that time as a student under Professor Gajin Nagao and several other professors, five to seven students would gather in one room and, like a seminar, you present your opinion and other people criticize and argue. Most of the time it ends up in argument on mostly late Mahayana Buddhist thought, like the Vijnana Vardin commentary on Nagarjuna, and Chandrakirti’s on Madhyamaka, on those kinds of intellectually stimulating subjects. “Yes,” my master said, “that’s ok, you can go to the monastery. But come back in three days,” he said. He meant I could escape from the monastery. He knew how hard it is. It was my birthday so, the next day, February second, I went. I was the second student, the deep snow blowing, in straw shoes and all new, top to bottom, dressed in new monks costume. Razor blades in my little bag, new oryoki. Certainly a cold head, newly shaved. Before,I had been growing hair so long it covered almost all my face. Fukui has the deepest snow in Japan. It’s coldest in the middle of the winter, big snowflakes. I went in the big, very big Mountain Gate. Above this Mountain Gate are statues of five hundred arhats, famous, immediate disciples of Shakyamuni Buddha. They were carved maybe three time as tall as this ceiling, and above that is the big hall where arhats are sitting, and you make many bows to this, under the shrine of the Mountain Gate, and then you enter into so-called tangario.

In tangaryo you sit all day from early morning, 3:30, to 9:15 in the evening. You cannot go into the main sitting part, but stay in the entrance room and pay attention to what you are getting into. You listen. You cannot walk around freely, but just sit there and listen. Where it is. Temple is big, very big, with many buildings...Instead of three days, I ended up staying two and a half years there, until right before I came to the United States. Tangaryo is like an entrance examination which tests whether you are able to stay and live in the monastery or not. Most students take about ten days to two weeks in this examination period. Ego is so big, so you have a very big problem. Not that ego is big, but people are forced to be independent and individual, not relying on other people or the support of a system. You get up on your own feet and are responsible for whatever you do. I was trained in Japanese society, just as all of you here, as very self-responsible, so I didn’t realize until later how big my ego was and how deeply rooted in body and mind.

Elder monks visit in this room where you are sitting. They come, walking swiftly, soundlessly with a big stick hiding in their sleeve. Their heads were all blue. Our heads were white, “tofu head,” we called it, new-shaved, so you can tell which is new and which is old. They came swiftly, soundlessly, and stood behind you and you start to shake. I was trained to argue properly at school, so I could argue with those trained monks logically, but monastery is certainly illogical place. When you respond, the answer is the huge kyosakustick, whack! whack! and each time your eyes pop out and stars go like that, sweat and cold, all at once.

Those kyosaku, today, I appreciate what it did to me. It’s like hammering the ego, crushing the ego. I was too proud... Their question was, why are you here? Zen talk, we called it. “Where did you come from? Why are you here? You could be anywhere else, why are you here? There are many other good teachers in Japan, why did you choose this?” Finally a little monk screams, “This is Dogen Zenji’s temple. I want to stay here!” You beg for training. Hearing that, they finally say, “You can stay.” By that time my ego has melted and is splashed everywhere on the walls. That was my first experience of brainwashing.

Schooling in Japan is extremely competitive and intellectual, but the monastery is opposite, quite physical. It’s like joining the Army. If you’re a fool or wise, it doesn’t matter. You have to be strong and ready on time. You cannot mess up the order with your own ideas. So, be on time, exact time, not too fast and not too slow, and ready to do anything. Serving elders. Kind to newcomers. Kind means very strict...

False pride was with me when I went to first dokusan, sitting like this, and my whole body was trembling. I didn’t know what to, how to talk, so I prostrated several times and sat in front of him. It is rare to sit face to face with somebody, so I directly faced him and looked into his eyes, and all of a sudden, something broke within me and tears came like a waterfall, and I couldn’t stop. Immediately Godo Roshi started to chant in a very low voice from the six hundred volumes of Maha Prajna Paramita Sutra,. He started from the very beginnning, chanting in front of me, and kept going and going and going. I knew the beginning of it, but I didn’t remember so much of it. He was chanting while I was crying, and finally he said, “It’s ok, go back to sesshin, go back and sit.” He didn’t ask why I cried.

I don’t know if they are crazy or what. Once in a while is fine, but sometimes an aged abbot would ask the head instructor to bring his stick, carved, inlayed, beautiful. The instructor appeared in zendo and start to hit everybody. “This is from abbot. This is from Zenji sama! Everybody has to get Pan! Pan! Pan!” (sound of hitting) That’s an encouragement from the abbot to you, even as a very beginner, so you say,, “Thank you very much! Thank you very much!” Very strong touch from your abbot. Monastery has its own very good nature from which I suffered so much at first. Why did I have to put hundreds of silk beddings on the floor in the big tatami room and make complete beds for about five hundred, sometimes one thousand laymen who came to stay in the monastery? Eiheiji is a monumental pilgrimage temple and Japanese lay families look forward to visiting it at least once or twice in a lifetime, to feel where their original temple is. So young monks are quite busy, getting food and beds ready on time. Besides sitting practice, there is a lot of chanting, a lot of cleaning, even there’s straightening the young cedar trees bent by the snow. All kinds of jobs we had. So physically, you have to be very strong, or become strong. The monastery is a wonderful place to think about before and after. When you are in the monastery, no thinking is best, just do it.

I was scolded at Eiheiji after the first meal. About three or four of us.. “You, you, you, you: don’t eat like pig!” About eighty people, young monks, their heads very soft and razor cuts showing that they are very beginners, are holding oryoki high like this, and between their arms, the old monk’s face comes up and he says, “You eat too much!” After every meal this old monk walks around and notices everything, and among all those people, I get all sweaty. It’s a kind of funny situation. Before I went to the monastery, I was feeling I was first class. At the monastery I was forced to realize that I am the worst kind! So when I came out from the monastery, my only one confidence was that everything is possible. That was my understanding. Everything is possible! Just take time, work on it for a long time, that was my learning in the monastery. Still lots of things to learn, especially because students here are very honest, you know.

There is no bullshit. I cannot be some sort of Zen Master, because as soon as I feel that way, a student comes and knocks me down on the floor! There are no trips. I appreciate it. X [student] is that kind of person to knock me down often.

My first formal sesshin was at Eiheiji. I’d sat many sesshins before, but they were with Sawaki Roshi, whom I admired very very much. I remember it was extremely hard, the constant patrol behind me was really bothering me. They carried quite a long stick, and when you start to move: Whack,like a wind comes and whack! You are hurt on the cushion! And during tangaryo, the entrance examination at Eiheiji monastery, I got very many kyosaku. [Student]:Why didn’t you go home?

Kobun: I felt very much at home there, so...it was good I stayed. They all beat my brains, scraped them, chopped them up. They are well-trained to treat head-oriented people. Use kyosaku very wisely on that ego. They beat me to death! They asked a question, and I was trained to answer every question, so I would start to answer, but before I finished, they started beating me. It wasn’t brain wash, it was beating a dirty rug, or something. They beat me until I was clean! That’s why I’m pretty strange. I never want to go back!

[Student]: Isn’t it true that when you were in charge of the young monks at Eiheiji, that you did not beat them. Kobun: I didn’t beat them. Out of respect to zazen, I couldn’t hit them. They are coming to practice at Eiheiji, so strong, and longing to meet with Dogen Zenji, the founder. So how to treat them properly was my basic subject. I went to abbot and explained that I had this job and is it alright to receive them? About eighty young monks came, their heads all shaved and cut everywhere because they haven’t shaved before. [Student]: So what did the abbot say? Kobun: “Fine. Fine. Try!” Out of eighty, I hit three students. And those were impossible! With encouragement, their shoulders are like football or soccer player! You could break a lot of kyosakus on them!

Second year of monastery, my master in Kamo, Niigata prefecture, telegraphed me and I rushed back to spend one month with him at his temple. I was his only disciple at that time, and he showed me very strange things. “Draw these, copy these in your handwriting.” Three materials on seven foot long pieces of silk, two feet wide, and you copy his material on to new silk. It shows where you stand in inner practice. Confirmation of the essence of your practice in action determines whether your own name is on this chart or not. Laymen can receive this also. If a layman has the potential for teaching people, by his teacher’s confirmation, permission, he starts to teach. Even if you have permission, if you do not want to teach in ordinary way, you don’t need to do so...After one month he said, “Now you can go back to the monastery or whatever you want.” So he kicked me out from his influence and I ended up living in this country. Still, every day I think of him, and about what was his intention to do this particular ceremony with me.

The title to my master is called Buddhabuchi. Shak kakushi butsu buddhabuchi. In Sanskrit you say Buddha bhumi. Bhumi is earth, great earth. Buddha land is what this means. My name was written on this circular chart and then connected to original Shakyamuni Buddha, so it’s a whole circle of names, but the name I have is not Buddha buchi, instead it is called “new Kobun.” A strange name! “New Kobun” “Shin Kobun.” What this means is, until you have successor you don’t receive this Buddhabuchi. Until you have a child, you are not called father, so to speak. So it’s a very big responsibility whether growing child truly becomes mature and able to conduct and accomplish their practice every day. It is this question I direct toward myself, and toward whoever I take care of.

Buddhabuchi. Look into your own view of the world and check whether it is seen as Buddhabuchi, and also, vice versa, when you look at your own inner world... and see the Buddha land within you or not. Since there is no inside or outside, even while there is inside, outside. Still, this equality of sameness inside world, outside world, has to be checked. Personally speaking, I don’t feel comfortable. I mean, I don’t fuss about my life, must for some reason, when people kill each other in front of my eyes, I feel my practice isn’t accomplished. If I take the place of that person who has to fight, I’ll be doing exactly the same thing as him or her. When the situation is like that, I get very confused. Confusion keeps my practice going. So the problem seems to be becoming bigger and more serious to me, while I am getting old and have less strength. I still see lots of problems.

Middle of winter, sesshin letter was piled up on the cushion. After morning service you go back to the zendo, the monks’ hall, and on your black cushion, piles of letters from the week. One of them was one of those red and blue international airmail letters. Who wrote this airmail to me? I knew nobody from another country. It was a letter from Suzuki Roshi inviting me to the United States to help with his new project. Tassajara began half a year after I received this letter. He needed somebody who knew Eiheiji, so I was picked.

Abbot, Taizen Kumazawa Zenji, was ninety six years old, and vice abbot was my favorite master, he was my master’s teacher. So this vice abbot is actually the one who said “okay” to Suzuki Roshi. This abbot, Taishun Sato Zenji, was old and blind, but whoever came to his room, even before they opened the shoji door, he knew who was coming and called the name. “Kobun-san, desuka?” “Yes, sir! Hai!” Cold sweat everywhere when I go. He could walk without an attendant everywhere in Eiheiji, which has thousands of steps. Sometimes a close attendant would trip, and he would laugh at him. “Very inconvenient to have open eyes,” he said.

....Did I tell you my sort of,I thought it was a kensho experience at Eiheiji. Oh! It was February? I sat so many sesshins there! Which?... It was snow. New snow came to the mountain, first snow. Rohatsu. Second year at Eiheiji. The first snow came, and about eight o’clock in the morning the sun hit the mountain and the snow started to melt very fast. You can see from the monk’s hall, which has a similar feeling to this room. It is maybe half the size of this one, and two huge hibachi were sitting there, and I came down to go to the bathroom and stopped in the shuryo, the monks’ hall. Before I went back to join the sitting again, I sat there, and through the window, about the same size as these windows, I could see snow, white snow on the deep green, huge, hundreds of years old cedar trees. Many many of them. And from drips of melting there were hundreds of millions of lights reflecting, and it was an incredible view. It was finished in five minutes or so. I was sitting there, and forgot to go back to sit!

It lasted about three months. I was kind of strange person to people. And you may feel that was kensho, but it is way before kensho. Many things, small things like that, happen one after another, and each time I thought, “Maybe thisis it. Oh, no,his couldn’t be it!”

Student: Kobun, when you thought you had your kensho experience, did you ask you meditation teacher about it? Oh, yes! Oh, yes! At that time he was one of the chief instructors at Eiheiji. Now he is Vice Abbot there. Very wonderful teacher. Ekiho Miyazaki roshi [?].

Of course, he still talks about it to my master’s wife, and to my mother, how cute I was! What a cute boy I was. Of course, I was the one who first jumped off the tan and ran into this instructor’s room. “What was it?” “It wasn’t it!”he said. “That’s wonderful. Just forget it. It’s gone!” So I obeyed. I forgot it. Of course, every one of you has had such outstanding experiences. You don’t know if you are upside down, or running, or stopping. Some very big thing takes place of you and you find out what it is.

So I ended up staying in Eiheiji for two years, and I became one of those wild geese! And one day Suzuki Roshi came. I didn’t know he came. He came like a wind, and went. Later on I found out that he had visited. About three months later I had that very experience I told you about, at the end of Rohatsu sesshin when I found twenty letters on my cushion. On the last morning of Rohatsu you don’t sit on your cushion anymore, so each monk had many letters on his zafu. There it was, Suzuki Roshi’s letter: Par Avion, and the stripe of red, green, white. Framed, sitting on those letters. That was my fate.

I don’t understand what has been going on. I don’t even try to understand why. Some kind of tension of connection, mind connection....It was supposed to happen and effortlessly it happened, as if by accident. Do you have this kind of experience? You must. No one planned it, you didn’t plan it, no one seems to have planned it, but certain things happen, and you feel, “Yes, it was supposed to happen.”Student: Were you excited about coming here?

Without letting me know, actually a lot of people were preparing to bring me here. Later on I found out what was happening. I did a small kindness to American students who were utterly stuck in the monastery. Suzuki Roshi had sent them, and they were having enormous difficulty. It’s beyond imagination. Literally, aliens had landed in the monastery! One was a regular member of Stanford’s football team. Huge. Muscles. When he stands, he really stands out. Small Japanese people.... He walked like a dinosaur! Another person was an English gentleman, taller than him, like a crane flying with those wild geese. Their knees hurt so much, and they wanted to eat chocolate, and they wanted to go to the dentist, and everything! So I ended up looking after them and protecting them from hardship. In Eiheiji monastery there is no freedom allowed! The only personal time is the fourth and ninth day. So every fifth day, after having been shaved by each other, your head newly shaved, and obviously many cuts everywhere, bleeding everywhere. How awful it is! 3:30 AM you wake up. Awful place to go. I want to encourage you to go!.... No, this is better.

They could speak no Japanese. I could only speak a little bit of English, but could listen to them carefully to hear what the actual problem was. Everyone thought they were lying, that they wanted to go to the hospital in order to take a break from practice. I ended up taking them to a doctor to check on their knees, and to a good dentist to fix their teeth. I didn’t know that was all reported to Suzuki Roshi, and Suzuki Roshi came to look at me in the zendo one day, though I didn’t know it.

In the second year in America, after Tassajara was about ready. To me it was going smoothly after two years, regulation was pretty good, everybody was serious, so I said, “The promised time has come. I have to go back to meet with my master. They are waiting for my return.” Suzuki Roshi said, “You can go, but you are the kind of person who should live in this country.” He gently said that, and didn’t explain why. Trudy Dixon, who suffered with breast cancer, was about to pass away, but was still coming to Tassajara to practice. A wonderful lady she was! One night I visited her room. She was lying down. Her body had blue light, an aura, her whole body covered with it. She said, “I have to go, but I very much appreciate that you are here to help us.” Those are the words that encouraged me to return.

So I went back to be an attendant to my master, and while I was there, there was a big storm, and my town was covered by a flood. Big water rushed out from the mountains and many houses were washed away. I ended up staying half a year in Japan to help clean up. There was my father’s temple by the Kamo River bank, and my master’s temple, which has a similar feeling to this place. There is a steep slope of hill coming down behind the temple. Rain washed away all the ditches, and a chunk of bamboo forest slid down. I had to work very hard to put them both back together!

Half a year later I went to my master and we sat face to face, quietly. He made green tea, and I drank. He said, “Are you going?” and I said, “Yes, yes, I am going again.” I won’t forget his face at that time. He said, “Suitable ability should be at the suitable place.” That’s all he said to me. My master was still in good shape, but getting old. His wife is getting a little softer. She was like my master’s master! Pushy and energetic and very sharp-tongued. You will be dead if she starts to criticize you! She said, “This temple doesn’t need two masters. You go somewhere!” I said, “Thank you!”

So I came back! He made me escape from Japan. Japan didn’t need my kind of person, I think.

But my master’s wife is getting soft, and my master’s eyebrows are getting really white, everything white, like his master. When I first saw him this time, on the way back from Sikkhim, he was using a bamboo cane for the first time. When he looked at me my first impression was that his eyes had turned to blue, and I was very surprised. Twinkling blue color. He looked very happy to see me. That was enough, and I spent some time with him, then came back here. It felt very good, just one glance.

He said he doesn’t need a second disciple. That’s what he told me, with a very intense feeling. “I don’t need anybody else as my student.” Since I came to America the congregation had been very disappointed in me and encouraged my master to take another disciple. They appealed to him for many many years. Finally, he said, “Okay,” so now I have a little Dharma brother in Japan who is taking care of my master. It feels very good. He is tall! Volleyball teacher. And he skis excellently.

Some day he is going to come and ski with me, he says. Togo is his name, meaning

East. Satori is in the East. To means East. That’s his name. He’s very handsome, and village girls are in love with him, he’s not married yet! Very happy situation! The year before, he visited Lhasa and told me about his visit. Very adventurous, very interesting person. I want to know him more.

Physical presence is final expression, that’s what I believe. But how to be so is a really big subject, so I am always very puzzled and very very careful to receive people who come to my house, and there are incredible scenes. I receive them all as my master’s visit, and my wife doesn’t understand that and treats people in a very harsh way, and I start to wonder, “Who is this woman? Is this the master acting like that?” She doesn’t receive, he doesn’t receive a second thing, do you say “second thing?” My master is a very very hard person to relate to! I will tell you, I love him so much, so I’ll tell it: When you go, be just as you are, and just as you are you should be. There is nothing that is necessary. Be just as you are. My wife is exactly like my master, it’s a favorable way to relate, so it looks like I have no way to go away from my master. She says, “It’s nice to have you at home,once in a while. Now it’s time you go to sesshin.” Always she says so, and kicks me out of the house.

While my master is alive, I wish you can all have time to see him. That’s partly why I’m here, to be a bridge for you. I may not go with you, but you can just walk on my back and find where he is. A very excellent man. I don’t know if he is a monk or priest or teacher or just country man. I cannot believe such a man exists. A monster, is the best way to say it! A very magically monstrous person. He had nothing to do with zazen, nothing to do with Soto or Rinzai. He didn’t speak about practice. And his wife is a very excellent lady, so women should go and see my master’s wife, too. Very good.

Going to see Master Chino, my Dharma master, is a great joy, but I cannot stay too long. I have to pull myself from his world as quickly as possible, otherwise sorrow remains. I want to stay with him and look after him until his passing. That is my job as his disciple. But he doesn’t like it, he wants me to do what he wanted to do himself, so I have to pull myself back and go in sorrow, and wander around in strange places. Departure is very very hard.

When I go back to Japan for a week I feel very shocked every day, and then slowly start to become Japanese, and before I feel I have become Japanese again, I have to pull myself out. Otherwise I wold have to say goodby to you! It’s a very very strong pull!

I have spent some long period in retreat, and after some experience of being alone, becoming kind of familiar with myself, it took a long time to come back to people and start to recover old relationships. Still working on it! I had a powerful admiration for people of knowledge. When I went to school to study, some people appeared like the ocean or the sky. It wasn’t artistic devotion and wish to serve that person, but an amazing longing to know things from the person whose experience after many many years had developed almost unreachable polished knowledge. That drew me. But I don’t encourage students to devote themselves to me, I don’t want to have any students! Too busy! I am a student still. After I become ninety years old, then you can start to hold my hand when I walk!

Most of of time my sitting is utterly dark, and very warm, and it feels like a fermented junkyard, or something. But once in a while a forgotten jewel is in there, so I treasure them. When I pull it out, it shines. Often I feel that the action of zazen itself saves me from so much heaviness of life. It brings me back to where I started. After about five or six sittings, my body feels very energized. To sit with you is a very wonderful excuse, actually. If I sit alone, zazen flips me away, throws me away. “You are no good!” Breaking many Precepts, one after another, I gave up zazen, and it was very foolish to do that. I mean, I thought I’m not worthy to do zazen. For this reason, I thank you very much that you pulled me out of the dark and let me sit with you! It is wonderful to sit seven days, even though I know what will happen, and what’s going on, still, it’s nice to have some slight new discovery, always.

One purpose of my life is, no military on this earth. No fighting, no creating weapons is my aim. Such gigantic energy, economy, spending...to make something else instead of making weapons. How to make it a concrete effort is a very big subject for me. Our mind is very powerful this way. When we lose a teacher, it is very shocking, it has a very powerful effect. When a student dies or goes away, it takes a long time to approve yourself. Trust and dependence is so tightly interrelated that it is very difficult to fill the empty gap. In twenty years of life, I fear we’ve lost many fellow practicers, unreturned friends. Even just thinking of it, you re-experience your anxiety again and again, as well as the great joy you shared together.

A temple is where your ashes are brought. You end there when you pass away. Your personal, individual life ends and you ask someone to bring them somewhere. That somewhere is the temple. So it has been from long ago, that this place [Jikoji] was a burial place before the first people from Europe came. I say “this place,” meaning this long strip of land, “Long Ridge,” you call it. For the benefit of living things here we could plan many things. Student : Do you think it’s your baby? I don’t know! You think so, I never thought so! I know, the other day people asked me about Kannon Do, “What are you going to do with your baby?” And the date of when this place could legally operate as a temple is the same day as Kannon do. And somebody tricked me, it was my birthday present, it was my birthday. “Oh no! I’m trapped!”

Student: So this wasn’t your idea? It happened! And of course I cannot do it alone. People who want to visit this place, do things here, should gather regularly. Continuing this place is secondary. Who comes here is most important to me. If I am here, I must limit people or I might make some kind of trip on others.If you put me in the teacher’s position, I am responsible as a last resort to stop this place, and to ask people to leave. But so far, I have never asked people to leave...But that is a negative kind of responsibility, an emergency case. So I want to know more about what you want to do on this land. Most residents here are caucasian. I’m kind of alien, so I mustn’t be your boss, that’s my feeling. It’s a kind of cultural problem, and I want to be very smart about this.

PDF: Kobun resume, June 1992

Lectures

Who Is Your Teacher?

The real purpose of practice is to discover the wisdom which you have always been keeping with you. To discover yourself is to discover wisdom; without discovering yourself you can never communicate with anybody. In everyday life, we can pick up some glimpse of wisdom, as the polished tool of the carpenter expresses that there is wisdom in the arm of the carpenter. It is invisible; you cannot draw it and show it.

Wisdom doesn't come from anywhere; it is always there as the exact contents of awakening—it is always there and everywhere. What you can do is to uncover it, like going to the origin of a river. Have you been to the source of a river? It is a very mystic place. You get dizzy when you stay for a while. An especially big river has several sources, and the real source, the farthest point which turns to the major stream, is moist and misty, with some kind of ancient smell, and you feel cold.

You feel, "This isn't the place to go in." There is no springing water, so you don't know where the source is. Actually, such a place exists in everyone; the center of us is like that. From this place, the ancient call appears, "Why don't you know me? Living so many years with me, why can't you call my real name?" Unfortunately, we cannot travel into such place with this body and mind, but we feel there is such an origin, and from there everything starts. From that place you have come, actually, and whatever you do is returning to that spot. In one lifetime you can meet with other people, at least one other beside yourself. So, in other words, two of you discover. This is why you are continuing to live so hard.

The way to discover your origin is to listen to the one with whom you feel, "This is it!" It looks like you can do it by yourself, without others, but actually, by yourself alone you cannot discover that origin. Reaching that point, you never believe, "This is it." But pointing to another's origin directly and saying, "That's my origin," at that moment another finger appears, pointing at you, and says, "No, that's my origin." And you get dizzy. "Wait a minute, are you my teacher or are you my student?" And both say, "No, it doesn't matter. I can be your student; I'll be an ancient Buddha for you." The student says this to the teacher. Without throwing your whole life and body into others you can never reach to your own true nature. The more your understanding of life becomes clearer, and more exact, and painfully joyful, the more you feel, "I'm so bad." The one who appears and says, "No, you are not bad at all, that is the way to go," that is your teacher. Don't misunderstand—this teacher is not always a person. It can embrace you like morning dew in a field, and you get a strange feeling, "Oh, this is it, my teacher is this field."

How to go with your true self is to deeply bow to yourself and ask, "Please, let me know about myself." Because we cannot do it alone, we have to do it with someone who is able to accept our vow. Letting such an occasion occur is what supreme awakening is. It is not your creation. You just admire the place where you are and be with it, and that place is the place to meet with your teacher. It doesn't need to be some special kind of place. When you are a little bit mindful about yourself you can create such an opportunity…between your children and yourself, between your parents and yourself.

On Breathing

Depending on each person, there is an inner image of what breathing in sitting is. As you notice, there is also a physical element of sitting and an invisible element of sitting, which we call mind. We do mind-sitting, body-sitting, and we let the breath sit. Three aspects to sitting exist because we can observe our sitting from three angles. We breathe naturally and appreciate our breath and really understand what the breath does to our body and mind. To really connect the three—body, mind, and breath—is the point.

During sitting, your breath should be very regular, very smooth, with almost no effort, not noticing that the air is gone, or has come in. Breath has an incredible range of volume, strength and speed. There are hundreds of techniques you can use, depending on your health and emotional condition. Like playing an instrument, singing, or drawing, you breathe; there are many ways. The basic point is not to push or pull, but to let it go.

The ancient Sanskrit word for breath was prana. This is translated as chi in Chinese or ki in Japanese—ki, as in aikido. Ki is vitality. Sometimes it is called seiki: life-vitality. And this soft part where our intestines are is called hara in Japanese. Hara is also called ikai: the ocean of ki. Our vitals are here. When you have no strength in the hara you feel very weak. When you are full of energy this part is full of energy.

When you chant you let your voice come out from this center of your stomach. Basically ki comes out and informs the shape of your mind. The contents of your mind is that voice. The ideal in sitting is to forget the breath. You may breathe as you like; there is an incredible variety in the speed of breathing, and even the emotion of breathing. So if you want to observe your breathing, you should do it for months and months without trying to control it.

My feeling is that each breath is an independent thing. It arises and goes and some thoughts go with it. You cannot bring them back. That's it. It's the same as your heartbeat—your whole body is needing it. So if you can forget the breath then you are having perfect breath. I suggest that you keep your posture straight, upright—good posture, that naturally takes care of the breath. From deep breath, which carries your awareness with it, to very shallow breath, which also carries your awareness, you have to choose the best breath between them.

You can be aware of the texture of your breath, from rocky breath to silk-like breath, and finally to transparent breath, like a transparent string of breath. You can feel which is the best breath for your sitting. Try to sit and pay attention to how your breath goes. Each time you sit, your body condition is different, so each time you must try to find your best breath and stay with that. Get really familiar with it. I always feel breathing is like drawing a circle.

The Other Side of Nothing

We don't do this practice expecting to obtain something by doing it. This is a very different kind of action. In one sense, it's quitting human business and going to the other side of the human realm. Have you noticed your face changing, moment after moment, when you are facing the wall? When you pay attention to exactly how you feel, you feel how it changes. It is such a slight change that no one would notice if someone observed you. It's like one flame of fire is sitting on the cushion. Every moment the texture of the flame is different. You experience this from morning zazen to night zazen. In every sitting there's a very different feeling. Each breath, all is different.

We experience some kind of dying in sitting, which relates with what's true and what's not true. What's not true dies, so we suffer. We wish to hang on to the self which we believe exists. The contents of what “I” means, or the pieces of the idea of the self, are consistent, but when you sit you observe no substance in those pieces of self.

If we try to achieve some awakening or enlightenment, it doesn't succeed. We hear that sitting is to clarify the true nature of the self, but it seems nothing is clarified, nothing happens. You just spend the time and have lots of pain and a stumbling mind. If you sit all day you have a good sitting once or twice, but when you compare the good sitting with the rest, you have a very regretful mind. "What was I doing? Drowsy, powerless sitting.”

Doubt arises in this. What is it? Is this alright? Are you okay? Your mind is in a different place than sitting. I wish you would sit alone sometime for several days. If you sit alone, although there are many dangerous situations to fall into, you feel you can clarify your right intention, your strict attitude about taking care of yourself. If we sit together like this you think, "Because other people sit, this might be alright! This must be the way!" If something more important than your concern about yourself occurs, of course you quit sitting and plunge into taking care of that. Actually, for each of us, the opportunity of sitting is the same as sitting alone.

Student: For years I always preferred to sit by myself, and every time I had to sit with a group, it was always more difficult. I had problems I didn't have by myself.

Kobun Chino Roshi: The difficulty wasn't sitting together; the difficulty was yourself! Wanting to be alone is impossible. When you become really alone you notice you are not alone. In other words, we stop our vigorous efforts towards ideal purity. Purity is just a process. After purity, dry simplicity comes, where almost no more life is there, and your sensation is that you are not existing anymore. Still, you are existing there. You flip into the other side of nothing, where you discover everybody is waiting for you. Before that, you are living together like that—day, sun, moon, stars and food, everything is helping you—but you are all blocked off, a closed system. You just see things from inside toward the outside, and act with incredible, systematic, logical dynamics, and you think everything is alright. When noise, or chaotic situations come, you want to leave that situation to be alone. But there is no such aloneness!

It is very important to experience the complete negation of yourself, which brings you to the other side of nothing. People experience that in many ways. You go to the other side of nothing, and you are held by the hand of the absolute. You see yourself as part of the absolute, so you have no more insistence of self as yourself. You can speak of self as no-self upon the absolute. Only real existence is absolute.

Aspects of Sitting

I'd like to reveal the natural nature of sitting fully as it is. If I put some concept on this, and make you understand what I think is an ideal way to sit, I would be a kind of special gardener who fixes boxes and lets you go through to become square bamboo. Or I would be an automatic newspaper man who runs a newspaper—whoever comes, I would just put you in the machine and make you flat, and you would come out a squished being, or something like this!

Too much talk about zazen, or shikantaza is not so good for you. It's impossible to teach the meaning of sitting. Until you really experience and confirm it by yourself, you cannot believe it. It has tremendous depth, and year after year this gorgeous world of shikantaza appears. It's up to you to cultivate it. Because you are buddhas yourselves, you can sit. Dogen named this sitting "Great Gate of Peace and Joy." Simply, it is peaceful—eternally peaceful, pleasurable and joyful. Shikantaza doesn't have the name of any religion, but it is, in its quality, a very true religious way to live.

Posture

Year after year our physical posture becomes polished. By repeated sitting our muscles become very refined, not pulling one way. When your muscles become very balanced you are able to feel almost nothing is there. Your intestines, your bones—all are in the same balance. When your body is able to take the right posture, when you sit as if no one is sitting there, you feel yourself. The way to find your best posture is to focus your attention on the feeling of your body. It's hard to say what it is, an inner eye, an inner sensation that is able to observe every part of your body.

When you are awake, you feel every part of your body—its surface, a little bit inside, deep inside, all parts. When you take the best posture you can possibly reach, at that time you are weightless and you aren't aware of your effort to keep that posture. The point is to have a stretched spine, with your neck straight along the spine. When you lean slightly right, or left, or backward, you can find which point is your straight posture. This is related to the incredible pull of gravity. A thousand million lines of gravity pull you down. You swing your body from left to right and finally you come to one point.

It doesn't continue that way. We again crumble down, so we have to build it up again. Maybe every twenty minutes or so we have to re-do it. It is a very natural position, but we have incredible habits that are hard to correct. Every time we correct our sitting position we always fall back into a more comfortable posture.

To have the foot soles facing upward is very important. To have your soles going upward, with your feet pressing down on your thighs, is not an accidental discovery but a polished discovery. They should be like that because then there is a very grounded sensation of being on the earth, not flowing, or flying purposelessly in the air.

The eyes should be kept open, and hopefully they'll see through everything, because your seeing is not "your" seeing—you should see through. It is very easy to mess up your posture just by rolling your eyeballs around. You don't have to stare. If you come back to keeping your eyes still then something opens up. All our sense organs are finely constructed awakenings. As you notice, all information from the sense organs comes together moment after moment, and the mind-eye is always functioning. Everyone has mind-eye; it does not newly open. Your sitting still is like a person who just shot an arrow: a moment later the result is there. What you know is the sense that the arrow is moving alright. It has left your realm but you sense it's running well. Stillness is like that.

In the stillness you see intuitions are going alright; you sense every kind of intuition.

The form of the human body is a continuity of karmic force. Without parents you would not exist here; without you, your children and all future generations could not exist. So in this sense, to have a body on this earth has a very karmic reason and result. Without this karmic condition you cannot exist as the expression of ultimate force.

You can say there is a "right posture" for sitting. Many times during sesshin you hit that "right posture" and then swing away from it, then go back to it. You understand what right posture is for you. You can see it, perceive it—it relates with your mind-state at that time. Right posture in sitting creates the contents of sitting from all that you have been experiencing up to now. It requires detachment from your desire to do it; you let it happen by itself. So right posture is not that you are doing sitting; right posture itself is the sitting, and the system of your whole body is going into that posture.

The period of sitting is not your own sitting. Physically you feel that it is your sitting that you do. The inner view of one's sitting, which is utterly an external view too, includes your personal existence. It includes everything, from which your mind is continuously working. The arising memories of whatever you've experienced are always there; no matter whether you deny them or accept them, they are there.

Not only that, as time passes the contents change. So posture is how to keep going. As you notice, this physical condition of existence is a very dynamic thing, which you cannot stop. It goes by itself. Maybe all things go by themselves; you are that, and you are able to experience and feel it.

Sitting is always pointless, you know. When we touch sitting with this body, it feels like putting a thumb on paper: "This is it!" Touching time/space, or creating matter in time/space. That's how I feel when I sit. The more sitting becomes still, almost stopping, the more it feels like time stops and there is no more distinction between this body and all other things. Things feel as if they are extensions of the body. It's not a frozen kind of realization, but a very powerful presence of the sensation that you are really there, as what you are, what things are, without naming each thing that's there. Even not-what-you-are is also there. I mean, the thing which holds the phenomenal, the experiential phenomenon that is your own body, is also yourself. Phenomenon and noumenon are there together.

A slight move of mind causes lots of insights out of past experience and out of images that you have been making toward the future. This causes imaginings about the relationship of all people and situations in the present time, with no distinction between past, present, and future. Just the enormous dynamic of where you live, what's there, all existing as yourself.

This body is a very fine thing at such a time, continuously pressing this sitting spot. If your mudra is perfect yet you sit slanted, this is strange. It is the same as sitting while you imagine that you are dancing somewhere. No one can see it; only you yourself can feel it. But dance is dance and sitting is sitting, so when you sit you must sit, instead of thinking of some fantastic thing. But it is not necessary to develop consciousness of the self alone. You have to release that conscious self about yourself. Otherwise "sitting very well" will catch you.

The time of sitting is timeless actually. When you take the right position, you have nothing to think about anymore, nothing to bring up from any place, past or future. That which can be called the present moment (where you are and what you are) actually is there, and the physical posture you take in sitting is a part of whole posture, where it actually is. So when you meditate, many, many things are meditating because, essentially, everything meditates in that space.

Udumbara

I have many things to think about and to discuss about how to live a really useful life in this new age. We'd like to look into and welcome the next century. Dogen Zenji said, "To master the Buddha's way is to master, to clarify, your own self. Through that, you can clarify the own-selves of all others." So he mentioned that the focus is to clarify your own life-and-death matter, birth-and-death matter: living this subject.

The subject is so close, pointing to yourself like this. If you point outside, we can study pretty well, but when you start pointing to yourself it is almost impossible. A fresh eye is opened toward outside, so the same eye cannot be used to see the interior realm of yourselves. We turn around and make our interior world an external object, and analyze what's happening, which is usually called psychology, or religious studies. But that kind of study, with objectified self, is not what we are. So a very important point is to be with the self who rejects analysis of any aspect.

Gary Snyder spoke of this same kind of situation as trying to grab an avocado seed. It slips...you cannot grab it! He got this American version from the famous painting, Chasing the Slippery Catfish with Gourd. Have you seen that picture? A young man, a bushy, hippy-like person, is chasing the catfish with a gourd, which has a very teeny entrance! Impossible to catch that fish! Japanese catfish have huge heads and long, long whiskers, and a tail-part that goes very teeny. The whole body is so gooey and slippery. The teeth very, very sharp, like a saw. The catfish usually lives in the pond. We call it "Master of the Pond." When you try to catch it, this causes an earthquake! Leave it alone! If you seek the truth, this causes an earthquake! That's how, some biographers say, many powerful people appear. When they finish their tasks and pass away, always earthquakes appear. It's not earthquakes, though; it's people's sleeping minds.

Blossoms—season of blossoms—not the regular season of blossoms, but off-season blossoms, bloom when such people appear and disappear, and that which is the (earthquake) sensation of people's minds, see that kind of blossom; they are the mind-blossoms of people who appear. We call those blossoms-of-mind "Udumbara." They bloom every 500-year period like that.

These teachings by Kobun Chino Roshi appeared in the newsletter of Jikoji Zen Retreat Center in Los Gatos, California.

Anecdotes from Stephan Bodian

Kobun was like an elder brother to me, as well as a teacher. When I left for Tassajara, he gave me warm woolen underwear he had worn at Eiheiji. When I returned on winter break between training periods, I stayed at his house, though I’m sure Harriet wasn’t happy about it.

As we all know, Kobun was unconventional and did things in his own unique and spontaneous way. When he ordained me a priest in 1974, he didn’t order new robes from Japan, as was customary. Instead, he gave me his own koromo (outer robe), okesa (ceremonial robe draped over the left shoulder), and an ancient silk rakusu he had received from his master. The rakusu was brown, a color generally reserved for those who had received transmission, but Kobun didn’t seem to care.

Later he said to me, “When you wear this robe, you’re invisible.”

When it came time to shave my head in preparation for the ordination, a task generally delegated to one of the other monks, Kobun offered to do it himself and then forgot to leave the small patch of hair (called shura) that was to be shaved off during the ordination itself. The head shaving was a very intimate prelude to the ordination. I felt like I was being stripped down to bare essentials.

* * *

Kobun was a good friend of Chogyam Trungpa, and the two would often spend time together when Trungpa visited the Bay Area. One day the two met in Sonja Margulies’s living room to drink tea and do calligraphy, with several of us in attendance. As one teacher looked on, the other would spread out a large piece of paper, kneel down, gracefully stroke some words of spiritual wisdom (Trungpa in Tibetan, Kobun in Japanese), and then translate what he had written. After a pause the other teacher would do the same. Before long the exchange became a kind of playful Dharma combat, with each man responding to what the other had written.