ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

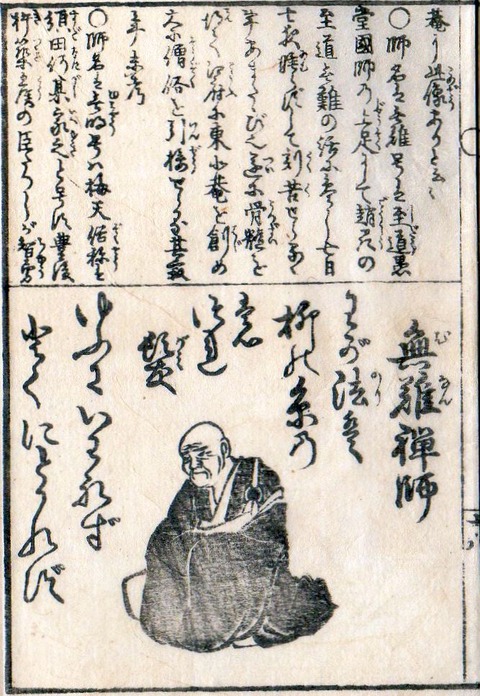

至道無難 Shidō Bunan [or Munan] (1603–1676)

Works

龍沢寺所蔵法語 Ryūtakuji Shozō Hōgo (1666)

即心記 Sokushinki (On the mind, 1670)

The Eastern Buddhist, New Series. 1970, NS03-2, Shidō Munan, Sokushin-ki, Trans. by 小堀宗柏 Kobori Sōhaku & Norman A. Waddell, pp. 89-118. PDF

The Eastern Buddhist, New Series. 1971, NS04-1, Shidō Munan, Sokushin-ki (2), Trans. by 小堀宗柏 Kobori Sōhaku & Norman A. Waddell, pp. 116-123. PDF

The Eastern Buddhist, New Series. 1971, NS04-2, Shidō Munan, Sokushin-ki (concluded), Trans. by 小堀宗柏 Kobori Sōhaku & Norman A. Waddell, pp. 119-127. PDF

自性記 Jishōki (On self-nature, 1672)

The Eastern Buddhist, New Series. 1975, EB8-1-08, Shidō Munan, Jishō-ki, Trans. by Kusumita Priscella Pedersen, pp. 96-132. PDF

無難禅師道歌集 Bunan zenji dōka shū (1844)

至道無難 Shidō Bunan by 田川悟郎 Gorō Tagawa

Bunan's Dharma Lineage

[...]

菩提達磨 Bodhidharma, Putidamo (Bodaidaruma ?-532/5)

大祖慧可 Dazu Huike (Taiso Eka 487-593)

鑑智僧璨 Jianzhi Sengcan (Kanchi Sōsan ?-606)

大毉道信 Dayi Daoxin (Daii Dōshin 580-651)

大滿弘忍 Daman Hongren (Daiman Kōnin 601-674)

大鑑慧能 Dajian Huineng (Daikan Enō 638-713)

南嶽懷讓 Nanyue Huairang (Nangaku Ejō 677-744)

馬祖道一 Mazu Daoyi (Baso Dōitsu 709-788)

百丈懷海 Baizhang Huaihai (Hyakujō Ekai 750-814)

黃蘗希運 Huangbo Xiyun (Ōbaku Kiun ?-850)

臨濟義玄 Linji Yixuan (Rinzai Gigen ?-866)

興化存獎 Xinghua Cunjiang (Kōke Zonshō 830-888)

南院慧顒 Nanyuan Huiyong (Nan'in Egyō ?-952)

風穴延沼 Fengxue Yanzhao (Fuketsu Enshō 896-973)

首山省念 Shoushan Shengnian (Shuzan Shōnen 926-993)

汾陽善昭 Fenyang Shanzhao (Fun'yo Zenshō 947-1024)

石霜/慈明 楚圓 Shishuang/Ciming Chuyuan (Sekisō/Jimei Soen 986-1039)

楊岐方會 Yangqi Fanghui (Yōgi Hōe 992-1049)

白雲守端 Baiyun Shouduan (Hakuun Shutan 1025-1072)

五祖法演 Wuzu Fayan (Goso Hōen 1024-1104)

圜悟克勤 Yuanwu Keqin (Engo Kokugon 1063-1135)

虎丘紹隆 Huqiu Shaolong (Kukyū Jōryū 1077-1136)

應庵曇華 Yingan Tanhua (Ōan Donge 1103-1163)

密庵咸傑 Mian Xianjie (Mittan Kanketsu 1118-1186)

松源崇岳 Songyuan Chongyue (Shōgen Sūgaku 1132-1202)

運庵普巖 Yunan Puyan (Un'an Fugan 1156–1226)

虛堂智愚 Xutang Zhiyu (Kidō Chigu 1185–1269)

南浦紹明 Nampo Jōmyō (1235-1308) [大應國師 Daiō Kokushi]

宗峰妙超 Shūhō Myōchō (1282-1337) [大燈國師 Daitō Kokushi

關山慧玄 Kanzan Egen (1277-1360) [無相大師 Musō Daishi]

授翁宗弼 Juō Sōhitsu (1296-1380)

無因宗因 Muin Sōin (1326-1410)

日峰宗舜 Nippō Shōshun (1367-1448)

義天玄詔 Giten Genshō

雪江宗深 Sekkō Sōshin (1408–1486)

東陽英朝 Tōyō Eichō (1428-1504) > 禪林句集 Zenrin-kushū

大雅耑匡 Taiga Tankyō (?–1518)

功甫玄勳 Kōho Genkun (?–1524)

先照瑞初 Senshō Zuisho

以安智泰 Ian Chisatsu (1514–1587)

東漸宗震 Tōzen Sōshin (1532–1602)

庸山景庸 Yōzan Keiyō (1559–1629)

愚堂東寔 Gudō Tōshoku (1577–1661)

至道無難 Shidō Bunan (1603–1676)

PDF: The Biography of Shidō Munan Zenji

(Kaisan

Shidō Munan Anju Zenji anroku)

Compiled by

Fufu-anju Enji (Tōrei Enji, 1721-1792)

With an Introduction by 小堀宗柏 Kobori Sōhaku PDF

Trans. by Kobori Sōhaku & Norman A. Waddell

The Eastern Buddhist, New Series. 1970, NS03-1, pp. 122-138.

PDF: Tokugawa Zen Master Shidō Munan

Thesis by Eduardo Cuellar

The University of Arizona, 2016

Shidō Munan (至道無難, 1602-1676) was an early Tokugawa Zen master mostly active in Edo. He was the teacher of Shōju Rōjin, who is in turn considered the main teacher of Hakuin Ekaku. He is best known for the phrase that one must“die while alive,”made famous by D.T. Suzuki. Other than this, his work has not been much analyzed, nor his thought placed into the context of the early Tokugawa period he inhabited. It is the aim of this work to analyze some of the major themes in his writings, the Jishōki (自性記), Sokushinki (即心記), Ryūtakuji Shozō Hōgo (龍沢寺所蔵法語), and the Dōka (道歌). Special attention is paid to his views on Neo-Confucianism, Pure Land thought, and Shinto- traditions which can be shown through their prevalence in his writings to have placed Zen on the defensive during this time period. His teachings on death are also expanded on and analyzed, as well as some of the other common themes in his writing, such as his teachings on kōan practice and advice for monastics. In looking at these themes, it is possible to both compare and contrast him from some of his better-known contemporaries, such as Bankei and Suzuki Shōsan. Additionally, selected passages from his writings are offered in translation.

SHIDO MUNAN

Richard Bryan McDaniel: Zen Masters of Japan. The Second Step East. Rutland, Vermont: Tuttle Publishing, 2013.

One of the temples for which Gudo had responsibility was located at Sekigahara, where the battle had taken place that established the primacy of the Tokugawa Clan. When Gudo was in the region, he stayed at a local inn and there he took an interest in the innkeeper’s son. The boy was being trained in the family business but showed intellectual promise above his station. Locally, he was known as the “Kana-writing boy” because of his skill in the cursive form of the Japanese syllabic script.

When he was fourteen years old, the boy accompanied his father to the old capital, Kyoto. Along the way, they passed through regions that had been devastated during the recent civil conflicts. These sights left a lasting impression on the boy, and, when he was in Kyoto, he made contact with Master Gudo and took up a lay practice of Zen.

In the Rinzai system, students were first taught susokkan, counting the breaths. When they achieved some degree of concentration, they were instructed to focus on the breath without counting. And, finally, when the student was deemed ready, the teacher would assign him a koan. The koan Gudo gave to the innkeeper’s son was taken from the poem written by the Chinese Sixth Patriarch, Huineng: “—from the beginning not a thing exists.” [cf. Zen Masters of China, Chapter Three]

Before he could complete his Zen training, the young man had to return to Sekigahara to take up his duties at the family inn. Whenever Gudo was in the area he would check on the boy’s progress. A number of decades passed in this manner. The boy grew to adulthood, married, and became his father’s successor as inn-keeper. Over time, he fell away from his practice of Zen and acquired a taste for sake and gambling.

Around the year 1656, Gudo was once more in the region and stopped at the inn to see how his former student was doing. When he arrived, he was greeted by the innkeeper’s wife who told the Zen master that her husband was out. She invited him to come in to wait for him, and, as the two sat together, they fell into easy conversation, during the course of which the wife confided that her husband had taken to drinking in recent years.

“When he drinks,” she said, “he can become abusive. He also gambles when he has too much to drink, and he always loses. Really, there are times when I think my children and I would be better off without him. But he’s my husband—what can I do?”

“Let me see what I can do,” Gudo suggested. “It’s late. You retire, and I’ll wait for your husband. But before you leave, would you please bring me a bottle of your best sake and two cups.”

The woman did as Gudo asked. Then she gathered her children together, and they retired to the sleeping quarters. Gudo remained in the main room of the inn, seated in meditation. Around midnight, the innkeeper returned home in a drunken-state and was embarrassed to find his teacher there. Gudo did not reprimand him for his behavior and, in fact, indicated the bottle of sake set out on a table. Gudo invited the innkeeper to share a cup with him, to which the man readily agreed. The two had several cups of wine, chatting idly, and eventually the innkeeper fell asleep on the floor.

When he woke the next morning, he found Gudo still seated in meditation before the family shrine.

“You are awake,” Gudo noted. “And it is time for me to return to the capital.”

The man was a little hung-over and humiliated that his teacher had seen him in such a disreputable condition. He mumbled a reply.

As Gudo tied his sandals, he remarked, “You know, human life is brief and all things pass away. When you spend your time drinking and gambling, you have no time for other things that may be much more important. Besides which, you bring sorrow to your family and those who depend upon you.”

The innkeeper broke into tears and admitted that he had known for some time he needed to change his behavior. He swore an oath to do so, starting that very day, and, as a sign of gratitude, he asked Gudo to allow him to carry his bags on the first stage of his journey. Gudo agreed and the two set off. When they had gone a fair distance, Gudo told the man he should return home. But the man asked to be allowed to accompany the Zen master a little further. Eventually they arrived at the next village, and, once again Gudo offered to take up his own bags. The man said he was willing to accompany Gudo a bit further.

The next time Gudo offered to take up his bags, the man shook his head, “I’ll go with you all the way to Edo.”

Once they came to the city, the man had his head shaved and entered monastic life at the age of 52. Gudo gave him the name Shido Munan, a phrase found in Xinxin Ming of the third Chinese Patriarch, Jianzhi Sengcan. [cf. Zen Masters of China, Chapter Two] The first line of the poem, in Japanese, reads “The Perfect Way (shido) has no difficulties (munan).”

After he achieved awakening, Munan underwent a radical change of life-style. He did not, however, become active in the Rinzai hierarchy. Like his master, Gudo, he recognized that the tradition was stagnating. The career and political aspirations of monks made up a large part of the problem. Even monks who had achieved awakening were subject to ambitions. The koan training system had been compromised; correct “answers” could be purchased from older monks; some monks discovered they had a knack for coming up with appropriate answers without necessarily having insight. In addition, temple schools often drew students more interested in developing skills in literature or the arts than in Zen training.

Traditionally, the emphasis in Rinzai training had been on the attainment of awakening, but Munan recognized that while awakening was important, it was not an end in itself. Rather he saw it as an aid that helped the monk reform his character. Awakening, he asserted, was relatively easy to attain. Practicing the way of the Buddha, on the other hand, was difficult, especially for one who had not seen into his true nature.

Even though a man leaves his home and lives simply with his three robes and a bowl on a rock under a tree, he still cannot be called a true Buddhist priest. . . . Yet if he does wish earnestly to become a true priest, he will realize that he has many desires and is possessed of a body which is endowed with eighty-four thousand evils, of which the cardinal five are sexual desire, cupidity, birth-and-death, jealousy, and desire for fame. These evils are the way of the world. They are by no means easy to overcome. Day and night, by means of enlightenment [awakening], you should set yourself to eliminating them one after another, thus purifying yourself.

Munan provided an example to others of the change in life he expected Zen practitioners to attain. He was a close friend of and mentor to Suzuki Shosan, who shared his opinions on many topics. Munan lived frugally in a hermitage with few physical comforts and gathered a small group of disciples around him who were able to emulate his ascetic lifestyle. Of these, only one would be designated his heir—Dokyo Etan.

Munan Zenji

http://zennist.typepad.com/zenfiles/2008/09/munan-zenji.html

Japanese Zen master Shido Munan was born in 1603 and died in 1676. Munan was highly venerated by Zen master Hakuin Zenji (1685–1768) who was the teacher of Hakuin's teacher, Shoju Etan. Of all the Japanese Zen masters, Munan had an extraordinary grasp of Mind. It stands to reason because he spent a long time on the path not being merely content following form, or words and letters, but understanding that seeing Mind and cultivating it is of the greatest importance. Like all of the best Zennists, Munan fully understood the importance of Mind in Buddhism (not to be confused with mind which is in a constant state of disturbance owing to the perturbations of carnal existence).

For Munan, in a nutshell, Mind is Buddha in which one fully awakens (bodhi) to their fundamental or original Mind (the primordial undisturbed Mind) which verifies itself as only it can. Thus, one goes from a state of corporeal sleep to awakening to Mind upon which all things are based.

Munan understood that real practice meant getting rid of the obstructions that prevent us from knowing the original Mind in its own natural state, undisturbed. He also realized that even after we have attained an initial glimpse of Mind (satori), we still have to practice, continually, removing as much of the remaining obstructions as possible. Accordingly, Munan said:

“If you can really get to see your original Mind, you must regard it as if you were raising an infant. In whatever you do such as walking, standing, sitting, lying down, be aware of Mind so that everything is illuminated by it, so that nothing of the seven consciousnesses (vijnana) soils it. If you can keep him [the new born Mind] clear and distinct, it is like an infant growing up becoming equal with the father.”

Raising this special infant means paying attention to it more and more—not the desires of the body. Munan regarded the body as the cause of delusion, and satori as seeing the Mind as being fundamentally free of the body. We may draw from this that the more we practice, correctly, the more the original Mind should become outshining so that the body becomes less and less of a burden for us. In this way, we see the truth of birth and death which only affect the body—never the original Mind. Indeed, the original Mind is empty, unborn, and bodiless.

Shidō Bunan

Waka poems

Translated by Lucien Stryk & Takashi Ikemoto,

In: ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews,

Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963, p. 15.

The moon’s the same old moon,

The flowers exactly as they were,

Yet I’ve become the thingness

Of all the things I see!*

When you’re both alive and dead,

Thoroughly dead to yourself,

How superb

The smallest pleasure!

PDF: A History of Zen Buddhism

by Heinrich Dumoulin, S.J. (1905-1995)

tr. by Paul Peachey

Pantheon Books, 1963, p. 232.

Bunan (1603-1676), a disciple of the Abbot Gudō (d. 1661)

of Myōshinji, from whose line of descent Hakuin was to come

two generations later, spent his declining years at the hermitage

of Shidoan.'? He loved the people and warned them against a

practice which, concerned only with personal enlightenment,

seeks out the solitude of mountain fastnesses and looks down

on people in the world. Such bonzes are "the greatest evil in

heaven and on earth. They pass through the world without do-

ing any useful work and are thus great thieves." He summa-

rized his understanding of Zen in the following terms:Man builds a house and lives in it, while the Buddha dwells in

his body. The householder resides constantly in the house, and

the Buddha resides in the heart of man. If through compassion

things and deeds become easy, the heart becomes clear, and

when the heart is clear thc Buddha appears. If you wish to clarify

your heart, sit in meditation and approach to the Perfected One.

In meditation turn over the evil saps of your body to the Per-

fected One. If you do this, you will surely become a Buddha.

. . . The enlightened one follows nature whether in walking or

standing, in sitting or reclining.Bunan wrote in the fluent Japanese kana style and composed

well-known koan in the thirty-one syllables of Japanese poetics.

A collection of "dharma-words" from his pen has been pre-

served.There are names,

Such as Buddha, God, or Heavenly Way:

But they all point to the mind

Which is nothingness....

Live always

With the mind of total nothingness,

And the evils that come to you

Will dissipate completely....

Not doing zazen,

Is no other than zazen itself;

When you truly know this,

You are not separate

From the way of Buddha.

Sayings of Zen Master Bunan

Translated by Thomas F. Cleary

In: The Original Face: An Anthology of Rinzai Zen, Grove Press, 1978. pp. 99-108.

People see others in terms of themselves. The vision of

fools is dreadful. If there is ambition in oneself, one will

see others on the basis of that frame of mind. He who

lusts looks with lust. Unless one is a sage, seeing is

dangerous. Even though there are people on the great

way, people who can see and know are rare. What a

waste. A wise man discerns the potential of others,

though they may not be equal to him, and makes use of

their level of understanding....

To acquiesce to the teaching of enlightenment, as it

is, directly abandon all things, merge with the body of

thusness and experience peerless peace and bliss, is no

more than a matter of whether or not you think of the

body. Although there are people who think this teach-

ing is true, it's hard to find someone who strives to

make it his own....

It is easy to keep things at a distance; it is hard to be

naturally beyond them....

There are no mountains to enter outside of mind,

making the unknown your hiding place....

While deluded, one is used by this body; when

enlightened, one uses this body....

• Asked of the supreme vehicle, Bunan said,

To let the body be free and not to cling to anything.

For this reason it is a great matter; thus it is a rare thing

in this age.Whether man or woman, you should first make

them see reality, and have them sit in meditation for

that; when their seeing of reality is complete, then you

should teach them to respond to any event.When virtually enlightened, have them preserve

that, so that bad thoughts do not arise; if they nurture

this for a long time, they will become people of the way.When virtually enlightened, if you teach them that

all things are it, most people will turn bad. Those who

only preserve enlightenment mostly are trapped in

sitting meditation and become devotees of discipline.

Whether it's good or bad to expound the great way

immediately depends on who you're talking to. You

must teach with understanding, not misunderstanding.You should always act with kindness and compas-

sion. People think that kindness and compassion mean

doing things, but actually giving people things is the

foremost kindness and compassion. Never to do or say

what is painful to others is kindness and compassion.When you do things which are unpleasant and

painful to others, even if you have a mountain of

treasure it will eventually be ruined. There is no doubt

about this. Thus, working diligently, there comes to be

no Buddha, no teaching; though living you are not here,

neither do you die, you don't remain in this world or go

to the next world-having become like empty space, you

don't even think of empty space. There is no body,

nothing at all—there is no thought of nothingness or of

being.O my body,

Used to being used at will,

Since there is no using body or me.Fire is something that burns; water is something that

wets; a buddha is someone who practices compassion.

Teaching people to be kind and compassionate to

others means imitating the Buddha. If you just practice

compassion, you will certainly become good . The basis

of compassion is purity of the mind. Purity of the mind

is "not a single thing." "Not a single thing" means

nothing at all; it is beyond the reach of speech, beyond

affirmation and negation. If there is any affirmation or

negation in your heart, it will be obstructed by that

affirmation and negation; if there is no affirmation or

negation, then heaven and earth are one. If there is

something, it separates you from heaven-this you

should well understand.The mind which knows nothing

Is a Buddha

By a different name.Since you will surely eventually die, you should set

your mind diligently on the way of enlightenment.

There is no enlightened Buddha outside your own

heart; always keep a pure and clean mind and heart.

When thoughts of your own body come up, as long as

such bad thoughts are always there, this life is but a

little while and you will fall into a hell and suffer

forever and ever; but even leaving that aside, in this life

you will suffer in many ways.When the heart is pure and compassionate, there is

no Buddha outside of this.Once you have been greatly enlightened, there is no

great enlightenment; when praying, there is no prayer;

when rejoicing, there is no one to rejoice. Living, there

is nothing living; dying, there is nothing that dies; there

is nothing existent or nonexistent. Though you have

physical form, you have no form; beyond being and

nonbeing, you let existence and nonexistence be, be-

yond affirmation and negation, you let right and wrong

be—While deluded,

It is things that are things;

When enlightened,

You leave things to their thingness.

•Things People Are Always Wrong About:

Hating to be fooled by others while liking to be fooled

by oneself.Knowing others die but not realizing one's own death.

Discriminating others' right and wrong while not acting

properly oneself.Suffering from want and not knowing how to avoid it.

Thinking that original nothingness is nothing.

Setting up something in the way of enlightenment.

Unless you enter the way of enlightenment, you cannot

preserve your body.There are those who perform memorial services without

respecting the Buddha in their own bodies.Considering enlightenment to be the teaching of the

Buddha-those who are enlightened are rare.Not knowing how to overturn bad impulses.

• Bunan's Regulations for Disciples

A monk is the greatest evil on earth; he goes through

the world without labor-he is a great thief.When the fruits of discipline and practice are

fulfilled and one may he a teacher of others, he is a

precious jewel in the world. There are innumerable

teachers of the ways of the world, but teachers of the

Great Way are rare.Do not use unwisely even a piece of paper or half a

penny.Be constantly austere with the body, and do not do

things for the sake of the body. The enemy of Dharma

and Buddha is the body.Look upon accepting things from others as like

poison. When you have completely realized the great

way, then you should accept those things which people

hold dear; this is because it helps those people.During the period of practice and effort, should you

be beaten and trampled by others, you should rejoice

that the effects of the deeds you yourself produced in

the past are being exhausted.When master Joshu was asked if a dog has en-

lightened nature or not, he said No. If you can really

understand this No, you will surely be free from doubts

about anything in or out of this world. For example,

when you first enter, you shatter being and nothingness.

Having shattered being and nothingness, if you nurture

it energetically, you break through the body. Having

broken through the body, if you work hard, you break

through the mind. Having broken through body and

mind, the original mind appears. When you reach that,

then there is no doubt about what the world-honored

Buddha taught: there are hells; there are heavens; there

are enlightened ones and devils, hungry ghosts and

animals; there is retribution. You will have no doubts at

all about the scriptures.As for fundamental nothingness, when for example

they sit and meditate people think that control of body

and mind is the basis of "not a single thing," but they

are all wrong. "Originally not a single thing exists"

refers to the absolute nonexistence of "body" and

"mind." When you reach here, paradises and hells

spoken of by the Buddha are certain; hungry ghosts and

animals certainly exist. Those who don't reach here talk

in various ways to become well' known, but since it

doesn't come from truth, their words and actions are

not in accord.

• Bunan used to say to his group,

There is no special principle in the study of the way;

it's only necessary to see and hear directly. Directly

seeing, there is no seeing; directly hearing, there is no

hearing. You must fuse inside and outside into one solid

thoroughly peaceful state before you can do this.Although you people are buddhas right now, yet you

don't realize it. If you know you go against the buddhas

and patriarchs, if you don't know you revolve in the

routine of birth and death. At this point, if you don't

have the transcendental eye, how can you attain reali-

zation?Knowing the fundamental,

Detached from myriad things;

Who knows that which is outside words,

Which the Buddhas and Patriarchs didn't transmit?Although our school considers enlightenment [sa-

tori] in particular to be fundamental, that doesn't

necessarily mean that once you're enlightened you stop

there. It is necessary only to practice according to reality

and complete the way. According to reality means

knowing the fundamental mind as it really is; practice

means getting rid of obstructions caused by habitual

actions by means of true insight and knowledge.

Awakening to the way is comparatively easy; accom-

plishment of practical application is what is considered

most difficult. That is why the great teacher

Bodhidharma said that those who know the way are

many, whereas those who carry out the way are few.

You simply must wield the jewel sword of the adaman-

tine sovereignty of wisdom and kill this self. When this

self is destroyed, you cannot fail to reach the realm of

great liberation and great freedom naturally.If you can really get to see your fundamental mind,

you must treat it as though you were raising an infant.

Walking, standing, sitting, lying down, illuminate

everything everywhere with awareness, not letting him

be dirtied by the seven consciousnesses. If you can keep

him dear and distinct, it is like the baby's gradually

growing up until he's equal to his father-calmness and

wisdom dear and penetrating, your function will be

equal to that of the buddhas and patriarchs. How can

such a great matter be considered idle? Now the reason

that we consider human life best is for no other reason

than being means to realize true liberation in this

lifetime. However, if you seek profit and support,

considering these the ultimate truth, in every moment

of thought used by delusive ideas, vainly ending your

life, at the time of death nothing you can do will be any

use. The Buddha came into the world to guide those on

the paths of illusion, directly pointed to the fundamen-

tal mind, letting them leave behind birth, death, and

myriad things. While this body clearly exists, clearly

realizing this body doesn't exist, while there are clearly

seeing, hearing, discernment and knowledge, clearly

realizing there are no seeing hearing discernment or

knowledge-this is called the effect of true investigation;

how could it be easy?When you go near fire, you are warm; when you go

near water, you are cool; and when you go near people

imbued with the way, they naturally make your mind

die and conceptions dissolve, causing all wrong

thoughts to cease. This is called the spiritual effect of

complete virtue. You all call yourselves people of the

way as soon as you enter the gate. Really, you should be

ashamed.

Shidō Bunan (1603–1676)

in Japanese Philosophy: a sourcebook

edited by James W. Heisig, Thomas P. Kasulis, John C. Maraldo

University of Hawai‘i Press, Honolulu, 2011. pp. 190-194.

A Zen master in the Myōshin-ji lineage of the Rinzai School, Shidō

Bunan (or Munan) is best known for his teaching that the best approach to Zen

would be “to die while you are alive” and then try to remain that way for the rest of

your life. One of Bunan’s disciples became the master of Hakuin, and thus the germ

of Hakuin’s notion of “the great death” of the self originated with Bunan. Grow-

ing up in present-day Gifu prefecture, when a Zen monk named Gudō Tōshoku briefly

stayed with his family, he was so impressed that in walking with the monk to see

him off, the boy ended up following him all the way to the big city of Edo, where he

was ordained and given the name Bunan, meaning “no problem.” Bunan attained

enlightenment at age forty-seven, according to one record, and built a small temple

for himself in the Azabu district of Edo, now one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in

Tokyo. Afterwards his reputation grew and he became spiritual advisor to a number

of daimyō. Bunan appears in a number of stories from that time, for example, one

of refusing a lord’s invitation by sending a note back that consisted of nothing more

than a splotch of ink made with a rice cake.[Mark L. Blum]

This Very Mind is Buddha

Shidō Bunan 1670, 5, 9–10–27, (89, 93–112)The reason death is abhorred is that it is not known. People them-

selves are the buddha, yet they do not know it. If they know it, they are far from

the buddha-mind; if they do not know it, they are deluded. I have composed

the following verses:When you penetrate the fundamental origin

You go beyond all phenomena.

Who knows the realm beyond all words

Which the buddhas and patriarchs could not transmit?If people know birth-and-death, it will be the seed of a false mind. Even

though I may be censured for having done so, I leave these trifling words scat-

tered here, in the hope they may be of help to the young and uninitiated.……

The nenbutsu is a sharp sword, good for cutting off one’s karma. But you

should never think of yourself as becoming buddha, for not becoming buddha

is buddha.When one’s karma is exhausted,

There is nothing at all.

To this, for expediency,

We give the name “buddha.”……

The teachings of Buddhism are greatly in error. How much more in error it

is to learn them. See directly. Hear directly. In direct seeing there is no seer. In

direct hearing there is no hearer.……

To a certain person I said, “As for the buddha-dharma, people today are

perplexed, and seek buddha outside of themselves. For example, in the term

“wondrous existence,” wondrous is original nothingness and existence is where

nothingness moves or operates. Nothingness can never be manifested without

being, which is why they are combined. One is known according to the right or

wrong of the dharma by which one lives. When one has insight into one’s own

nature in all one’s behavior in everyday life, and uses one’s body in accordance

with this nature, then we may speak of the buddha-dharma.People say that enlightenment is difficult. It is neither difficult nor easy;

nothing whatsoever can attach to it. It stands apart from the right and wrong

of things, while at the same time corresponding to them. It lives in desires and

it is apart from them; it dies and does not die; it lives and does not live; it sees

and does not see; it hears and does not hear; it moves and does not move; it

seeks things and does not seek them; it sins and does not sin. It is under the

domination of causality, and it is not. Ordinary people cannot reach it, and even

bodhisattvas cannot actualize it. Therefore, it is called buddha.While one is deluded, one is used by one’s body. When one gains awakening,

one uses one’s body.The teaching of Buddha is, after all nothing, yet how foolish the human

mind of man is (to interpret it in various ways). There is nobody in the world

who is not deluded by fame. It is understandable that people get lost in sexual

desire or the acquisition of wealth, but if they become aware that even those

things are in vain, what then is fame? If you single-mindedly follow the path of

the Buddha, other things will be settled one way or another. It is worthless to

cling to fame.A person’s delusion by fame

Is the greatest folly in the world.

People should be as those

Who know not even their own name.One usually sees others in the light of one’s own standards. The way a foolish

person sees is very dangerous; because of one’s greediness one sees others as

greedy. A sensual person sees others as sensuous. It is dangerous for anyone but

a sage to judge others. Even if there were a person who followed the great Way

of the Buddha, few would recognize such a one correctly. As a consequence of

this, the great Way is degenerating.A wise person handles others using keen insight into their natures, and

makes what they have in their minds operate usefully, even though their natures

are quite different. Then they will come to work properly. One who leads others

should keep these things in mind.It is easy to live consciously apart from worldly affairs. To live without con-

sciousness apart from worldly affairs is difficult to achieve.For instance, fire burns things, and water makes them wet. But fire is not con-

scious of burning things, nor is water conscious of wetting them. A buddha has

compassion for all beings and is not conscious of that compassion.……

The person who tries to enter the great Way without having seen a true mas-

ter will suffer from sexual desire and cupidity. Such a one will be greatly in error.

One who wishes to live in the great Way should consider that the defilement

that permeates all existence is produced wholly by one’s own body. One has to

have a keen insight into what is common, not only to heaven and earth, but to

the past, present, and future as well. Having seen this, if one keeps the oneness

of this within, there is no doubt that such a one will be freed naturally from the

karma of the body and will become pure.A certain person asked me, “What is the way of Mahayana, the Great

Vehicle?” I said, “In the Great Vehicle, you are upright, and there is nothing to

observe.”“Then,” it was asked, “what is the way of the ultimate vehicle?” I said, “In the

ultimate vehicle, you do as you will, and there is nothing to observe. It is a won-

derful thing, and it is very rare in this world.”I said to my disciples: “When you labor over kōan, why do you indulge in

so many difficult things? All things you do are your seeing directly, hearing

directly.”Master Rinzai said, “There is a follower of the Way who listens to the dharma

and depends upon nothing…. If you have awakened to this non-dependence,

there is no buddha to be obtained.” Huineng, the sixth patriarch, attained

satori upon hearing the words of the Diamond Sutra which say, “Awaken the

mind without fixing it anywhere.”……

Everything has a time for ripeness. For instance, as a child, one learns the

alphabet. Then, as an adult in the busy world, there is nothing one is unable to

write about, even about things of China. This is the ripening of the alphabet.

People who practice Buddhism will suffer pain while they are washing the

defilements from their bodies; but after they have cleansed themselves and

become buddha, they no longer feel any suffering.So it is with compassion. While one is acting compassionately, one is aware of

his compassion. When compassion has ripened, one is not aware of his compas-

sion. When one is compassionate and unaware of it, one is buddha.Since all compassion

Is the work of bodhisattvas,

How can misfortune

Befall a bodhisattva?……

There is nothing more ignorant than a human being. While walking, sitting, or

lying, people suffer pain and sadness, mourn the past, fear the uncertain future,

envy others, and consider things from their own point of view alone. Thus they

are bound in sadness by the affairs of the world. Their life in this world is spent

in worthless pursuits. Yet in the worlds to come, no matter how they may suffer

from pain in their successive lives, they will be unable to rid themselves of them.

Indeed, the human being is possessed of deep delusions.……

A priest is said to be one who possesses a solid appearance (having long prac-

ticed zazen). His external aspect and his inner being have become completely

one. He is, after all, like a dead man revived. A dead man wants nothing; he

needs neither to flatter nor hate any person. Having attained the great Way, he

naturally sees the right and wrong in others, and is able to lead them to the Way

of Buddha. This is a priest.……

To one who asked me how to practice the great Way in everyday life, I said:

Ordinary people are themselves buddhas. Buddhas and ordinary people are

originally one. Therefore, one who knows is an ordinary man, and one who

knows not is a buddha.……

To someone who practices nenbutsu:

Unless you recite the name,

There is neither you nor buddha.

That is it—

Namu-Amida-Butsu.To a priest who preaches the dharma:

When it has totally perished,

You are nothing but nothingness itself—

Then you may teach others.……

On the Buddhist life’s abhorrence of knowledge:

You should remember,

Knowledge stems

From the various evils of others,

And your own evils as well.On Rinzai:

You became a monk—

A commandment-breaker monk—

Because you killed the buddhas

And the patriarchs.……

Grass, trees, land, and state, all are to become buddhas.

There are no grasses or trees;

There is no land, no state;

Still more,

There is no buddha.……

To a person suffering from life’s troubles:

Consider everything you do

As the practice of the Way of the buddha,

And your sufferings will disappear.On teaching the Way:

Do not be deluded

By the word “Way”;

Know it is but the acts

You perform day and night.[Kobori Sōhaku, Norman Waddell]

From the Mumonkan, Case 37:

http://moosiszenjourneys.org/joshus-oak-tree/

A monk asked Joshu in all earnestness. “What is the meaning of the patriarch's coming from the west?”

Joshu said, “The oak tree there in the garden.”

There is a wonderful story about this koan. Shido Bunan Zenji was travelling along the Tokaido road from Kyoto to Edo. He was being followed by a robber who put up at the same inn as Shido, planning to rob him during the night. The thief opened the door and peeked in. To his astonishment, what he saw there in the room was a garden with an oak tree in it. Suddenly, he heard a voice exclaim, “Who's there?” The tree transformed into Shido sitting in meditation. The thief was so stunned that he apologized and asked to learn about this amazing technique that allowed him to change into an oak tree. The teacher taught him to do zazen and gave him a koan. In time, the man changed and lived an honest life.

Zengo 90

至道無難唯嫌揀択

Zengo: Shidō bunan yuiken kenjaku

Translation: The Supreme Way knows no difficulties, only avoid picking and choosing.

Source: Shinjinmei (Faith-Mind Maxim).

From

久須本文雄 Kusumoto Bun'yū (1907-1995)

禅語入門 Zengo nyumon

Tokyo: 大法輪閣 Daihōrin-kaku Co. Ltd., 1982

An Introduction to Zen Words and Phrases

Translated by Michael D. Ruymar (Michael Sōru Ruymar)This is an old and well-known Zengo taken from the first two lines of the

Shinjinmei composed by Sengcan (d. 606), the Third Patriarch of Zen in China. The

Shinjinmei is a poem comprised of 146 lines of four-word verse presented in a sonorous

style that well expresses the essence of Zen, while those two lines in particular provide

the essence of the Shinjinmei.Student-teacher dialogues with Master Zhaozhou (778-897) that include these two

lines appear in both The Record of Zhaozhou and The Blue Cliff Record (cases 2, 57, 58

& 59). Otherwise famous for his Mukōan, Zhaozhou was so especially fond of the phrase

shidō bunan that he adopted the Buddhist name Shidō’an, and greeted his callers with it.

Of those who achieved Great Enlightenment from the shidō bunan kōan was Zen Master

Shidō Bunan (1603-1676), the Dharma heir of Zen Master Gudō Tōshoku, three time

resident and chief abbott of the Myōshin-ji Temple. Taking the tonsure, he changed his

name to Bunan, and late in life followed Zhaozhou by calling his home Shidō’an, or, Shidō

Hermitage, where he passed his remaining years. In that way, the phrase shidō bunan

holds something that draws the mind of Zen practitioners.Shidō refers to the Supreme Ultimate Universal Way, the highest Truth, the

Buddhist Path, the Buddha Mind, the Buddha-nature, Self-nature and Dharma-nature.

Bunan means that which is without difficulties. “The Way is near,” said Menzi, meaning

the Supreme Way is not something far away at a great height, but is within the closest

reach of our daily lives, and is not difficult to attain. Also, yuiken kenjaku is to be read

tada kenjaku o kirau, where kenjaku is “to choose,” (erabu) or “to prefer” (yorikonomi),

that is, “to pick and choose,” (shushu sentaku). To avoid (kirau) picking and choosing

means that it is not good to adopt a dualistic perspective of ‘yes versus no,’ ‘good versus

bad,’ and ‘like versus dislike.’The “mind” of the Shinjinmei: Faith-Mind Maxim is the alpha and omega of

existence, also referred to as the Buddha Mind, Buddha-nature, True Thusness, and Self-

nature. Originally unborn, undying, formless and unstruck, it is that spiritually illumined

Absolute Existence which can neither be known nor seen. It is due to our dualistic,

discriminating intellect that picks and prefers (eri-konomi) that we are unable to awaken

to the mind that forms the root of this existence, or master the Supreme Way. If we cut off

this relativistic consciousness and establish ourselves in Absolute awareness, it is easy to

master the Supreme Way (i.e. Buddha Mind or Buddha-nature). In that way, as in

expressions like “both forgotten” and “cutting off both heads” (Zengo 6), emptying

opposites of their opposition is a precondition to awakening to the Mind of the Buddha,

one’s True Self.

Shidō Bunan 至道無難 has the following poem [歌]: 「生きながら死人となりてなりはてて思ふがままにするわざぞよき 」

Live by becoming completely and utterly dead;

then, doing as one pleases is [always] good.

In Living by Zen (1950, 1972: p. 124) Suzuki gives the following English translation:

“While living, be a dead man, thoroughly dead;

Whatever you do, then, as you will, is always good.”

Zen Master Shidō Bunan (d. 1676)

in 柴山全慶 Shibayama Zenkei (1894-1974), “A Flower Does Not Talk: Zen essays” (Tokyo and Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1972) at 46

“Die while alive, and be completely dead,

Then do whatever you will, all is good.”

Shibayama explained that “the aim of Zen training is to die while alive, that is, to actually become the self of no-mind, and no-form, and then to revive as the True Self of no-mind and no-form.”

Shidô Bunan Zenji

by

山田耕雲 Yamada Kōun (1907-1989)

And there is really a person who hates the word Buddha. His name is Shidô Bunan Zenji. As you might know, he was the teacher of Shôju Rôjin, who was the master of Hakuin Zenji. I consider Shidô Bunan Zenji to be a truly outstanding person. Shidô Bunan Zenji was originally the innkeeper of a watering place along the Tokaido Road at that time. He became a student of the Zen master Gudô Oshô.

愚堂東寔 Gudō Tōshoku (1577–1661)

愚堂東寔像 自賛 狩野探幽筆

江戸時代 慶安元年(1648)This Gudô Oshô traveled back and forth several times between Kyoto and Edo (present-day Tokyo) along this highway and evidently stayed at this inn a number of times. As a result, Shidô Bunan began to receive the instruction of Gudô Oshô and eventually devoted himself to authentic practice. He decided to become a monk. Up to then he had devoted himself to carousing, to the extent that the family became quite disgusted with him. When I ask myself why he was carousing so much, I can surmise that he wanted everyone to think that he was no longer required at the inn, so that he would then be free to become a monk. Once when Gudô Zenji was traveling from Kyoto to Tokyo, he stayed overnight at the inn. The two men talked until deep in the night. The next morning Gudô Zenji continued on his way. Shortly after that, the master of the inn left home, never to return again. He went to Tokyo and practiced in a little hut-like dwelling. This was probably his continued practice after realizing enlightenment. As time went on, word got around that a very special person was living in the vicinity. Shôju Rôjin wanted to meet a true Zen master and traveled to Tokyo with that intention. I'm not sure if Shidô Bunan already called his hermitage Shidôan starting around that time, but at any rate Shôju Rôjin visited him in his dwelling. When he paid a visit, he found Shidô Bunan Zenji sitting in a ramshackle dwelling on worn-out tatami matting. But one look was enough for him to confirm that he had met his true teacher. This really speaks well for Shôju Rôjin.

Shidô Bunan Zenji was definitely not a learned man, but he nevertheless wrote truly outstanding waka poems. Also outstanding are his dôka or “songs of the way.” You would all do well to give them a perusal, if you have a chance. I have been looking over just the ones consisting of four lines. Many of them warn us against being duped by the concept of Buddha (hotoke-sama). Here is an example: “Even if you fall head first into Avici hell, don't ever think of becoming a Buddha” (sakashima ni abijigoku e otsurutomo hotoke ni naru to sara ni omouna). The Avici hell is the most gruesome of the traditional “eight hells” of Buddhism. This is truly outstanding. Shidô Bunan Zenji doesn't mince words. I believe such penetrating individuals are rare in the Rinzai School. I personally believe he is a match for Dôgen Zenji when it comes to his profound state of consciousness. Here is another verse of his: “No matter what, no different from an ordinary person, Buddhas and patriarchs are great devils” (nanigoto mo bonjin ni kawaru koto nashi busso to iu mo daima nari keri). He uses the word “devils” to indicate concepts. Here is yet another verse: “What is Buddha? Fools have started saying it, and people are deluded by something without a name” (hotoke to wa nani baka na yatsu ga iisomete na mo naki mono ni mayoi koso sure). Who is it that started saying Buddha? What fools they are! The real thing is nothing at all. It is because they attach a name like Buddha to it that they are all deluded. He has clearly realized his true self. Here is yet another verse: “When I hear someone asking what Buddha is, I feel like my ears have been dirtied” (hotoke wa to tazunuru koe wo kiku toki wa mimi no kegagaruru kokochi koso sure). Here is a Japanese who can compose such poems.

This is the time to take a second look at Shidô Bunan Zenji. He is of a different sort than Hakuin Zenji, we might say. He is different in character. Hakuin Zenji was a genius, especially when it came to literary gifts to compose texts and poems. Shidô Bunan Zenji could be said to have been completely lacking in such breeding and culture. There are almost no difficult statements in his writings. For example, with him there is no taint or trace of having read such works as the Blue Cliff Record, Gateless Gate or Book of Equanimity. When it comes to Shôju Rôjin, we can clearly detect the traces of his having read the Blue Cliff Record. A copy of that work could be found in the hermitage Shôjuan where he resided. As for Hakuin Zenji, there were many literary remains in the form of his voluminous writings. In that sense he was an inimitable genius. Nevertheless, I believe he needs to undergo further inspection when it comes to his enlightened dharma eye. This is not the time or occasion for me to speak in detail about this matter, and I feel that I that I must delve myself more deeply into the matter. Let me just say here that I hold Shidô Bunan Zenji in great esteem. His spirit is expressed well in these first words of today's Introduction: Becoming a buddha, becoming a patriarch: This is nothing but wearing dirty names and is therefore to be abhorred. This is how it is when you have reached the true fact. It won't do to become attached to ideas or names.