ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

安田天山 Yasuda Tenzan (1909-1994)

天山守宏 Tenzan Shukō

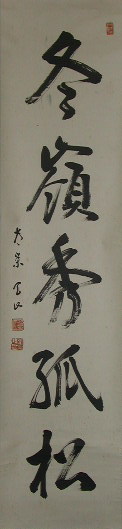

『冬嶺秀弧松』

Calligraphy by Yasuda Tenzan

![]()

安田 天山(やすだ てんざん)

明治42年~平成6年(1909年~1994年)

道号は天山、法諱は守宏。室号は耕雲また指月庵。俗姓安田。岐阜市西改田出身。

7歳の時、京都東福寺山内霊源院の安田維清和尚につき得度、のちに同善慧院の

爾以三和尚に師僧転換する。

昭和5年(1930年)滋賀県の永源僧堂に掛搭。その後、久留米梅林僧堂、鎌倉

円覚僧堂を経て、京都東福僧堂に転錫、家永一道老師の法を嗣ぐ。

東福寺山内栗棘庵住職を経て、同27年9月、常栄僧堂師家に就任。同53年

10月、退任。昭和61年より平成3年(1991年)まで東福寺派管長を務める。

Dharma Lineage

釋宗演・釈宗演 Shaku Sōen (1860-1919), aka 洪嶽宗演・洪岳宗演 Kōgaku Sōen; Soyen Shaku

ˇ

古川尭道 Furukawa Gyōdō (1872-1961)

Furukawa Gyōdō (1872-1961) was born in Shimane Prefecture. He trained under a variety of Zen masters, including Shaku Sōen and Nantembo. Gyōdō became Sōen's Dharma heir and eventually succeeded his master as abbot of Engaku-ji in Kamakura.

ˇ

安田 天山守宏 Yasuda Tenzan Shukō (1909-1994)

Another fellow disciple: 辻双明 Tsuji Sōmei (1903-1991)

Interview with Master 安田天山 Yasuda Tenzan (1909-1994)

by Lucien Stryk & Ikemoto Takashi [池本喬 1906-1980]

In: ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews

Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963, pp. 148-160.

The 3,000 square meter garden behind 常荣寺 Joei-ji Temple in Yamaguchi City is called 雪舟邸 Sesshūtei, Garden of 雪舟等楊 Sesshū Tōyō (1420-1506).

It is believed that the garden was commissioned by the 29th generation Lord Masahiro Ouchi sometime in the 15th century, and certainly Sesshū was in Yamaguchi at that time, along with many other artists and nobles from Kyoto, who had fled the war-torn capital, and who helped to keep Kyoto culture alive during this period.

Like other Zen gardens of the Muromachi Period, there are few plants in it, though the forested hillside bordering the garden is considered a part of the garden. It is believed Sesshū designed the garden after he returned from China, and so it reflects some Chinese influence and is based on a landscape painting of Sesshū's.The Joei Temple in Yamaguchi City is known

throughout Japan for the rock garden laid behind it

by Sesshu (1420-1506), Zen master and one of the

greatest painters in the Chinese style. The garden has

been lovingly preserved by generations of Zen priests

who doubtless were chosen to serve at Joei for their

personal qualities. Yasuda-Tenzan-Roshi, the present

master of Joei, possesses such qualities. He is very

well known, even revered, in Yamaguchi as an expert

in the art of tea and one who is familiar with the

other arts historically associated with Zen.From all over Japan people converge on Joei Tem-

ple, usually on Sundays and often in large tour groups.

But on weekdays it is possible to feel isolated there,

and apart from the pleasant sound of ducks paddling

in the garden pond and, alas, the occasional blare of a

loudspeaker giving a description of the garden when

such is requested, there is silence.The garden lies at the foot of one of the many fair-

sized mountains circling the city, and the impression

made on the visitor is that of a perfect unity of art

and nature, a Zen ideal. One is at a loss to define

where the garden ends and the mountain slope begins,

so well did Sesshu's genius achieve this desired unity.

The mountain is thick with pine and bamboo, through

which a path winds from the garden, and at times the

whole appears to be one gigantic various tree. Wan-

dering up the path alone, one may find oneself having

some rather strange bird-like illusions.It is autumn, the most beautiful season in Yama-

guchi, and Takashi Ikemoto and I are looking forward

to the exchange on Zen with the roshi. The appointed

day is a fine one, and though as in the case of our first

interview with a master we haven't prepared ques-

tions, we feel confident that the meeting will be a

fruitful one. We bicycle out to Joei and are met at

the gate by the roshi himself. Our greetings are very

informal, and the roshi leads us to a room with a fine

view of the garden, which I have grownto love, and

immediately begins preparing green tea on a brazier.

It has been decided that this time, in the interest of

consistency, we ask our questions separately (if I know

him as well as I think, Ikemoto-san will insist that I

ask most of them). At his insistence I begin.STRYK: Roshi, it is very good of you to take the time

to answer our questions, but please, if you find any of

them too sensitive, say so.ROSHI: Open mindedness, I like to feel, is character-

istic of Zen masters, especially when you compare them

with those of other Buddhist sects. I've nothing to hide,

though of course I can't promise to answer questions

that are too personal.STRYK: I have heard that wabi (the spirit of poverty

and self-denial) is rarely to be found in modern tea

ceremonies, and that most people attend them to show

off their finery. As a well-known tea master you are in a

position to know; is this true? We know that everything

in modern society would tend to make a mockery of

seeking wabi. Is the tea ceremony as it was originally

performed by masters like Rikyu (1521-1591) doomed

because of this?ROSHI: I agree with what you say about wabi. You

find all too little of it in tea ceremonies these days,

something I'm always complaining about to those who

attend the monthly ceremonies here. But you must

bear in mind that though wabi is a state of scarcity, it

doesn't mean lacking in things. Rather they should be

cast aside, or at least not used, nor even seen, during

the ceremony; the ideal is to minimize life's essentials.

Suppose you live in a mansion. You should have tea in

a room of four-and-a-half mats or less. After all, the

spirit of tea is the spirit of Zen itself, and can be de-

scribed with the words simplicity, conciseness, intui-

tion. I'm afraid that ceremonies today are like those in

the feudal castles before Rikyu's time. People prize, as

they did then, expensive utensils and what not. It was

from the time of the master Enshu (1579-1647) that

the cult began to introduce artistic elements. Needless

to say, in the old days women did not take part in the

ceremonies. Nowadays the ceremony is not serious

enough for my taste. It's like a social gathering, a rec-

reation for well-to-do women. Yes, I feel with you that

tea as conceived by masters like Rikyu may be doomed,

though, I hasten to add, there will always be a core of

traditionalists.STRYK: While we're on the subject of tea and Rikyu,

in reading accounts of his last ceremony with his inti-

mates, at the end of which he was on Lord Hideyoshi's

order to commit suicide, I have been disturbed by a few

of the things that are supposed to have happened.

You'll recall that after breaking the cup with the words,

"Never again shall this cup, polluted by the lips of mis-

fortune, be used by man," and then dismissing his

friends save for the most intimate of them all, he killed

himself "with a smile on his face." Now, it seems to me

that the breaking of the cup and his expression of self-

sorrow, however justified in the human sense, were

neither in keeping with the spirit of tea nor the famous

stoicism of Zen. When we compare Rikyu with Socra-

tes, who died by poisoning himself in almost exactly the

same circumstances, Zen does not come out as well as

Greek stoicism. Have you yourself ever been disturbed

by what I have sensed to be an inconsistency in Rikyu's

final act?ROSHI: I'm not certain that the breaking of the cup

is a historical fact, but if it is a comment must be made.

First of all, you must understand that Rikyu, though a

great tea master, was very far from attaining perfect

Zen, which is clearly revealed in his death poem, a most

unsatisfactory one from the Zen standpoint. Take for

example the line, "I kill both Buddhas and Patriarchs."

I'm afraid that contains very little Zen, and it shows

that he failed to reach the state of an "old gimlet," or

mature Zen-man, one whose "point" has been blunted

by long use. The Zen title "Rikyu" had been given him

by his teacher Kokei in the hope that it might help him

soften his temper, but all that was in vain. Kokei once

praised Rikyu in a poem, speaking of him as "an old

layman immersed in Zen for thirty years," yet one can

surmise, Rikyu was unable to discipline himself through

use of the koan. Incidentally, as you probably know, it

was Sotan, Rikyu's grandson, who created the wabi tea

cult. Sotan had taken a regular course of Zen study.

From what I've said, I hope you see that Rikyu was not

a true Zen-man and for that reason cannot be com-

pared, at least as a representative of Zen, with a great

sage like Socrates.STRYK: That's most interesting. Now, if you'll permit

me to change the subject and ask one of those sensitive

questions I threatened you with, I'd like to begin by

saying that I'm troubled by two seemingly minor things

in contemporary Japanese culture, as it relates to tem-

ples, gardens and monuments. And, if you don't mind

my saying so, both are to be encountered right here at

the Joei.ROSHI: Don't hesitate to ask your questions.

STRYK: Thank you. Well, the first concerns the use of

that loudspeaker out there. I realize that it is used to

inform visitors of the very interesting history of your

temple and Sesshu's garden, and that loudspeakers are

used in exactly the same way at all the famous places in

Japan, yet because of the blaring it's not really possible

to feel the calm which, among other things, one comes

to find. As loudspeakers serve merely an educational

end, could not printed information suffice? The other,

more important thing I have in mind is the apparent

need to supply obvious "comparisons" for visitors. In

Akiyoshi Cave we are informed that certain formations

resemble mushrooms, others rice paddies, etc. Here at

your temple some of the garden rocks out there are sup-

posed to look like mountains in China, and of course

both Akiyoshi Cave and Sesshu's garden have their

Mount Fujis. Even the world-famous Ryoanji rock gar-

den in Kyoto is spoken of in this way. It all amounts

to an aesthetic sin, I'm inclined to feel, and I use a

word as strong as that because such naive analogizing

runs s.trongly counter to the genius of Japanese art

which, most would agree, consists of great subtlety and

suggestiveness, as in Basho's poetry. Finally isn't it true

that Zen, being very direct in all matters, would insist

that a rock is a rock? I have it on good authority that

masters like Sesshu did not themselves make these curi-

ous comparisons. Why not leave it to the visitor to

imagine for himself, if he is so inclined, what such

things look like?ROSHI: Fundamentally no information about the gar-

den is necessary, I suppose, but really, you know, in

order to appreciate his garden fully you must have al-

most as much insight as Sesshu himself. This, needless

to say, very few possess. Ideally one should sit in Zen

for a long period before looking at the garden; then one

might be able to look at it, as the old saying goes, "with

the navel." But to answer your questions, one at a time.

As things stand I'm obliged to resort to such devices

as the loudspeaker, especially when a large, hurried

group of tourists comes, because, frankly, most of them

would scarcely bother to read printed information. The

"blaring" you hear out there, unpleasant as it may be,

serves an end, you see. After all, it's important to me at

least that as many people as possible are informed of

the essentials of Sesshu's gardening. Next, the problem

of supplying "comparisons." Sesshu, it is true, left no

written record of this type. The description of the gar-

den given today seems to have started in the Meiji era

(1867-1912). Nevertheless it's most important to keep

certain things clear. Sesshu was the first Japanese

painter to adopt the technique of sketching, which in

his hands became something like abstract painting. As

the Zen method of express on is symbolic, it is likely

that Mount Fuji out there (and you'll have to admit

that the rock does look like it) represents Japan, while

some of the other mountain-rocks represent China,

and so on. In other words the garden is an embodiment

of the universe, as seen by a Zen master. In short, those

are symbols you see out there, not naive resemblances.STRYK: I understand, but perhaps what I have in

mind is the tendency itself. For example, last Sunday I

visited a Zen temple in Ube, and the priest was good

enough to take me around the back for a look at the

garden. A very beautiful one, I should add. Well, with-

out even being asked he began pointing to the rocks

and shrubbery and offering comparisons. As the garden

is laid on a slope, it appears that the azalea bushes

which fringe the foot of the slope (they're not in bloom

now, of course) represent clouds. Frankly I wish he had

simply permitted me to take a look at the garden. But

perhaps we've spoken enough about the few things that

have troubled me, and I must say that you have an-

swered my questions about them with the greatest

forbearance. Something I saw inside the temple at Ube

leads me to my next question. A group of men were

sitting inside having tea, and when I asked the priest

about them I was informed that they had come to con-

sult him about the traditional Zen-sitting for laymen,

which, I understand, usually takes place twice a year,

at the hottest and coldest times. These men formed a

very mixed group, it seemed to me, and I've heard that

those who come to temples for zazen represent all walks

of life. Is that right? What is it they seek? Are they

troubled? Do any of them succeed in attaining satori?

Do you preach to them in a special way? As you see it,

is the zazen session as necessary in these days of psy-

choanalysis and so forth, as it was in the past? What, in

short, has the layman to gain by lodging in a cold Zen

temple, eating only rice and vegetables, and while sit-

ting in Zen, being whacked if he so much as dozes? Fi-

nally among those who come to your temple for the

sessions are there some who work, in one way or an-

other, in the arts?ROSHI: Most of the people who come here are stu-

dents who, for the most part, are merely restless. They

want hara (abdomen, or Zen composure). Then there

are the neurotics who come accompanied by their pro-

tectors, and older people who are troubled in one way

or another. Many come simply for the calm, others,

university lecturers, for example, because they are not

able to find as much in other religions. I'm afraid that

very few of them, whatever their reason for coming,

attain satori worthy of the name. They mayor may not

be given a koan, but after all one's problem can be

koan enough. I give a teisho (lecture on a Zen text) on

such books as Mumonkan or Hekiganroku. Addition-

ally, and this is a feature of the Rinzai sect, there is

dokusan, or individual guidance. Whether the session

ends in success or not depends on the temperaments of

the participants and on the efforts they make. On a

slightly different subject, perhaps you know that Pro-

fessor Kasamatsu of Tokyo University has conducted

experiments, through measuring brain waves, on Zen

priests engaged in zazen. He's found that even those

who've been sitting for as long as twenty years do not

have "tranquilized" brain waves. But I seriously doubt

the importance of such experiments. As to whether

those who come here for zazen are in any way con-

nected with the arts, I suspect so, but really we don't

go into such things.STRYK: You are aware of the great interest in Zen in

the West. Some feel that it is due to the same needs

that made Existentialism and phenomenological think-

ing so popular in the years following World War II.

Briefly this might have been due to a kind of enlighten-

ment, a sudden need for simplicity, directness, and the

formation of a world of real things and manageable ex-

periences. In other words, the disillusionment with

high-sounding phrases, idealistic concepts, and intel-

lectualism generally, forced men to search out some-

thing radically different. In some measure Zen seems to

offer an adequate substitute for the unrealizable prom-

ises of idealism. Is this your feeling too? Finally do you

think that, given the major reasons for the need of so

great a change in the way men view living, as far as the

West is concerned, Zen can, among other things, teach

us how to achieve peace?ROSHI: It appears that the great interest in Zen in

the West is motivated by utilitarianism. This may be

good or bad, but it's important to bear in mind that

Zen does not aim directly at simplicity. The Zen-man's

chief aim is to gain sa tori, to which simplicity, direct-

ness, and so forth, are mere adjuncts. Indeed it is quite

impossible that there be an awakening without such

mental tendencies. In this respect, I gather, Zen seems

to be able to satisfy the new spiritual needs of the

West. Really, you know, in one sense Zen is the only

religion capable of helping the world achieve peace. Its

fundamental teaching is that all things are Buddhas-

not men alone but all things, sentient and non-senti-

ent. And not merely the earth, but the other planets as

well. Universal peace will be realized when men all

over the world bow to the preciousness and sacredness

of everything. Zen, which teaches them to do this, is

the religion of the Space Age.STRYK: My final question deals with the arts and

touches on Sesshu and your temple. What would you

say are the chief qualities of Zen art, be it painting,

poetry, drama, or gardening? To put the question in

another way, and to narrow it considerably, when you

look at a scroll by Sesshu, when you look out at this

marvelous garden, in what way do you feel his crea-

tions to be different from those works of Japanese. art

which, though perhaps equally important, have no con-

nection with Zen? Last of all, what is there about West-

ern art, if anything, that might leave you as a Zen mas-

ter dissatisfied?ROSHI (returning from a back room with an album

of Sesshu reproductions): What expresses cosmic truth

in the most direct and concise way-that is the heart of

Zen art. Please examine this picture, "Fisherman and

Woodcutter." Of all Sesshu's pictures, this is my favor-

ite. The boat at the fisherman's back tells us his occupa-

tion, the bundle of firewood behind the woodcutter

tells his. The fisherman is drawn with only three strokes

of the brush, the woodcutter with five. You couldn't

ask for greater concision. And these two men, what are

they talking about? In all probability, and this the at-

mosphere of the picture suggests, they are discussing

something very important, something beneath the sur-

face of daily life. How do I know? Why, every one of

Sesshu's brush strokes tells me. I'm sorry to say that I'm

not very familiar with Western art, though occasionally

I'll drop in to see an exhibition. To be sure, Western

art has volume and richness when it is good. Yet to me

it is too thickly encumbered by what is dispensable. It's

as if the Western artist were trying to hide something,

not reveal it.STRYK: Thank you for answering my questions so

frankly and thoughtfully. Now it's Ikemoto-san's turn.IKEMOTO: Thank you. My questions will be of a more

personal nature. To my knowledge, Roshi, you are the

only qualified master in this prefecture. Please tell us

about your career from the beginning.ROSHI: I was born of peasant parents and went to

live in a temple in my sixth year. In those days it was

customary for one of the children of a religious family

to enter the priesthood, and an uncle of mine was a

Zen priest. I began to study Zen in the second year of

Junior High School, but it was only after the university

that I underwent serious training. The temples I chose

for this purpose were Tofukuji, Bairinji, Yogenji, and

Engakuji, which are located in different parts of the

country. I obtained my Zen testimonial from Ienaga-

Ichido-Roshi, chief abbot of Tofukuji. I learned from

him how to handle koans in the way favored by the

Takuju school of the Rinzai sect, but I also desired to

know how to deal with koans according to methods

used by the Inzan school of the same sect (it seems a

pity to me that few students of Rinzai Zen nowadays

desire to know a bout both schools), so I went to En-

gakuji in Kamakura. There under the master Furukawa-

Gyodo-Roshi I succeeded in my purpose. His strictness

impressed me. His own teacher, by the way, was the

famous Shaku-Soen-Roshi, one of whose lay disciples is

Dr. D. T. Suzuki of Western fame. Soen-Roshi, a schol-

arly master, was very different from Gyodo-Roshi, of

course, but both were great masters.IKEMOTO: Could you tell us how and under what

circumstances you achieved satori? I ask you to do this

because reading an account of your experience may en-

courage students of Zen.ROSHI (his face brightening): It happened on the

fifth day of the special December training at Yogenji,

while I was engaged in what is called night-sitting. As

is sometimes done, a few of us left the meditation hall

and, choosing a spot in the deep snow near the river,

began our Zen-sitting, each of us engrossed in his koan.

I was not conscious of time, nor did I feel the cold.

Suddenly the temple bell struck the second hour, time

of the first morning service, which we were expected to

attend. I tried to get up, but my feet were so numb

with cold that I fell to the snow. At that very instant it

happened, my satori. It was an enrapturing experience,

one I could not hope to describe adequately. This was

my first sa tori; now about my second. But you may be

wondering why more than one satori?IKEMOTO: I understand that it often happens to true

Zen-men.ROSHI: It was the second satori, experienced at En-

gakuji, that gave me complete freedom of thought and

action. As I've already said, Gyodo-Roshi valued activ-

ity above all else. He gave me Joshu's Mu as koan. Well,

for a whole year every view of it I offered was curtly re-

jected by the master. But this was the Inzan method of

dealing with the koan. At any rate, one day on my way

back from sanzen (presenting one's view of a koan to

the master) and while descending the temple steps, I

tripped and fell. As I fell I had my second satori, a

consummate one. I owe a great deal to Gyodo-Roshi,

for without his guidance I might have ended up a mere

adherent of koans, a man without insight into his true

nature, which is afforded only by an awakening.IKEMOTO: Most interesting, Roshi. By the way, this is

the so-called "instant age." I wish there were a special

recipe for gaining satori instantly.ROSHI: Well, the master Ishiguro-Horyu is said to

have devised a way of training toward that end. It's

rather easy to get Zen students to have special experi-

ences, such as hearing the sound of falling incense ash

or feeling themselves afloat. But that's not satori. Sa-

tori consists in a return to one's ordinary self, if you

know what I mean-the most difficult thing in the

world.IKEMOTO: I understand. Finally may I ask whether

you are training successors?ROSHI: A Zen master is duty-bound to transmit the

nearly untransmittable truth to at least one successor.

But everything depends on circumstances. You see, it's

not a matter of five or six years. A training period of

fifteen to twenty years is necessary. I am awaiting the

appearance of earnest seekers after the truth.