ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

沢庵宗彭 Takuan Sōhō (1573-1645)

Tartalom |

Contents |

Takuan Szóhó

Füleki András

PDF: Mystères de la sagesse immobile PDF: L'esprit indomptable |

PDF: The Unfettered Mind:

PDF: Soul of the Samurai: Modern Translations of Yagyu Munenori's "The Book of Family Traditions" & Takuan Soho's "Subtlety of Immovable Wisdom" & Takuan Soho's "Notes of the Peerless Sword"

PDF: Tao Te Ching: Zen teachings on the Taoist classic / Lao-tzu and Takuan Soho; PDF: Sword of Zen: Master Takuan and His Writings on Immovable Wisdom and the Sword Taie PDF: Zen and the Creative Process: PDF: Undisturbed Wisdom by Takuan Sōhō |

Takuan Sōhō (沢庵宗彭) (1573–1645). Japanese ZEN master in the

RINZAISHŪ, especially known for his treatments of Zen and sword fighting. A

native of Tajima in Hyōgo prefecture, he was ordained at a young age and later

became a disciple of Shun’oku Sōon (1529–1611) at Sangen’in, a subtemple of the

monastery DAITOKUJI, who gave him the name Sōhō. In 1599, Takuan

followed Shun’oku to the Zuiganji in Shiga prefecture, but later returned to

Sangen’in. In 1601, Takuan visited Itō Shōteki (1539–1612) and became his

disciple. In 1607, Takuan was appointed first seat (daiichiza) at DAITOKUJI, but

he opted to reside at Tokuzenji and Nanshūji, instead. Takuan was appointed abbot

of Daitokuji in 1609, but again he quickly abandoned this position. Takuan later

became involved in a political incident (the so-called purple-robe incident; J. shi’e

jiken), which led to the forced abdication of Emperor Gomizunoo (r. 1611–1629)

and in 1629 to Takuan’s exile to Kaminoy ama in Uzen (present-day Yamagata

prefecture). Takuan had befriended Yagy ū Munenori (1571–1646), the

swordsman and personal instructor to the shōgun, and while he was in exile

composed for him the FUDŌCHI SHINMYŌROKU (“Record of the Mental

Sublimity of Immovable Wisdom”). This treatise on Zen and sword fighting

draws on the concept of no-mind (J. mushin; C. WUXIN) from the LIUZU TAN

JING (“Platform Sūtra of the Sixth Patriarch”) to demonstrate the proper method

of mind training incumbent on adepts in both the martial arts and Zen meditation.

Takuan later returned to Edo (present-day Tōkyō) and, with the support of

prominent patrons, became the founding abbot of Tōkaiji in nearby Shinagawa in

1638. He died at the capital in 1645.

Takuan Sōhō

http://www9.ocn.ne.jp/~shounji/eng/yurai.html

Takuan Sōhō was born in 1573 in the town of Izushi, in what was called Tajima province (present-day Hyōgo Prefecture). He entered priesthood when he was still very young and trained under the tutelage of Shunoku Sōen from Sangen-in, a sub temple of Daitokuji temple in Kyoto and received the priest’s name Sōhō. In 1601 he visited the town of Sakai and continued his training under Ittō Shōteki from Yōshun-an temple, from whom he received the recognition as Zen master with the name Takuan. In 1607 Takuan became head priest of Nanshūji in Sakai. Two years later he was also named head priest of Daitokuji, but he left the temple after a stay of only three days and returned to Sakai. In 1615, after the summer battle of Osaka, Nanshūji burnt down and was rebuilt by Takuan at the present site. At the same time the temple Kaieiji was relocated from another site to the temple precincts of Nanshūji and Shōunji temple was built on the former grounds of Kaieji. Takuan became the founder of Shōunji.

In 1628 conflicts arose around the succession of Daitokuji and Takuan was banished to Dewa (Yamagata Prefecture). After a general amnesty, Mito Yorifusa, Yagyū Munenori and Tokugawa Iemitsu all became followers of Takuan. He then was appointed as founder of Tōkaiji, a temple in Shinagawa (Tōkyō), which was built in 1635 especially for the Tokugawa family. Thus Takuan linked Eastern and Western Japan with his teaching. Documents show that in the same year he was nominated by the Emperor as a National Teacher (kokushi), but he refused to accept the title and worked that it was instead bestowed on the first abbot of Daitokuji, Tetsuō Gitei.

Takuan died in December 1645 and was named founder of the rebuilt temple Nanshūji by his disciples and followers. During his life he excelled in Japanese poetry and haiku and also studied Japanese painting under Bokkei, Gyokukan and others. He was also well known by tea ceremony practitioners.

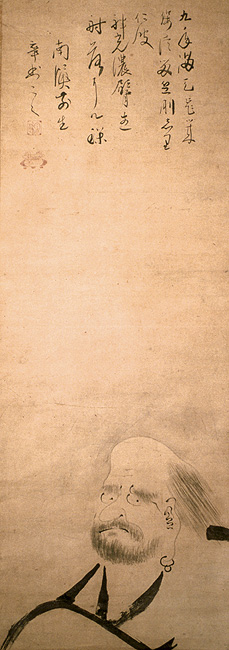

Daruma by 沢庵宗彭 Takuan Sōhō (1573-1645)

Hanging scroll(s), ink on paper

84.9 x 30.5 cm

Immovable Wisdom. The Art of Zen Strategy. The Teachings of Takuan Soho

by Hirose Nobuko

Floating World Editions, 1992, reprint: 2014, 181 p.

PDF: Sword of Zen: Master Takuan and His Writings on Immovable Wisdom and the Sword Taie

by Peter Haskel

University Of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu, 2012, 208 p.

Takuan Sōho's (1573–1645) two works on Zen and swordsmanship are among the most straightforward and lively presentations of Zen ever written and have enjoyed great popularity in both premodern and modern Japan. Although dealing ostensibly with the art of the sword, Record of Immovable Wisdom and On the Sword Taie are basic guides to Zen—“user's manuals” for Zen mind that show one how to manifest it not only in sword play but from moment to moment in everyday life.

Along with translations of Record of Immovable Wisdom and On the Sword Taie (the former, composed in all likelihood for the shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu and his fencing master, Yagyū Munenori), this book includes an introduction to Takuan's distinctive approach to Zen, drawing on excerpts from the master's other writings. It also offers an accessible overview of the actual role of the sword in Takuan's day, a period that witnessed both a bloody age of civil warfare and Japan's final unification under the Tokugawa shoguns. Takuan was arguably the most famous Zen priest of his time, and as a pivotal figure, bridging the Zen of the late medieval and early modern periods, his story (presented in the book’s biographical section) offers a rare picture of Japanese Zen in transition.

For modern readers, whether practitioners of Zen or the martial arts, Takuan’s emphasis on freedom of mind as the crux of his teaching resonates as powerfully as it did with the samurai and swordsmen of Tokugawa Japan. Scholars will welcome this new, annotated translation of Takuan’s sword-related works as well as the host of detail it provides, illuminating an obscure period in Zen’s history in Japan.

沢庵宗彭頂相(宗鏡寺蔵)

Takuan’s Dharma Lineage

[...]

南浦紹明 Nampo Jōmyō (1235-1308) [大應國師 Daiō Kokushi]

宗峰妙超 Shūhō Myōchō (1282-1337) [大燈國師 Daitō Kokushi

徹翁義亨 Tettō Gikō (1295–1369)

言外宗忠 Gongai Sōchū (1315–1390)

華叟宗曇 Kasō Sōdon (1352–1428)

養叟宗頤 Yōsō Sōi (1375–1458)

春浦宗熙 Shunpo Sōki (1408–1495)

實傳宗真 Jitsuden Sōshin

古嶽宗亘 Kogaku Sōkō (1465–1548)

傳庵宗器 Denan Sōki

大林宗套 Dairin Sōtō (1479–1568)

笑嶺宗訢 Shōrei Sōkin (1490–1568)

一凍紹滴 Ittō Shōteki (1539–1612)

澤庵宗彭 Takuan Sōhō (1572–1645)

PDF: Soul of the Samurai: Modern Translations of Yagyu Munenori's "The Book of Family Traditions" & Takuan Soho's "Subtlety of Immovable Wisdom" & Takuan Soho's "Notes of the Peerless Sword"

by Thomas Cleary

Tuttle Publishing, 2005, 128 p.

[The original text of the translated works is printed in standard typeface. Dr. Cleary's commentary on the text is printed in italic type.]

THE INSCRUTABLE SUBTLETY OF IMMOVABLE WISDOM

By Zen Master Takuan (1573-1645)The Affliction of Ignorant States of Fixation

Ignorance is written with characters meaning "no enlightenment" and refers to confusion. A state of fixation is written with characters meaning a "state of lingering" and refers to the fifty-two stages of Buddhist practice. Within these fifty-two stages, wherever the mind lingers is called a state of fixation. Fixation means lingering, and lingering means keeping the mind on something, whatever it may be.

The fifty-two stages of Buddhist practice are detailed in the Flower Ornament Scripture. Zen usage of scriptures and systems is concerned with essence rather than form, so doctrine and practice are considered expedients to be ultimately transcended. Abstract fixations are considered as inhibiting as concrete fixations, and Zen teachings demonstrate a great deal of effort to overcome the tendency to become attached to mental objects. The practical expedients for Zen awakening are likened to medicine, which is used to cure illness and not to be taken once health is restored. Similarly in the Zen approach to martial arts, learning postures, moves, and techniques is a matter of expediency for the master of martial arts must be able to respond to situations instantly as they unfold, without stopping to think about postures, moves, and techniques.

To express this in terms of your martial art, the moment you see an opponent come with a cutting stroke, if you think of parrying it right then and there, your mind lingers on the opponent's sword that way, so you fail to act in time; thus you get killed by the opponent. This is called lingering.

The cognitive mind conceives constants in the flux of phenomena and flow of events, but in the context of combat, where instantaneous adaptation to the unexpected is essential, this "freeze frame" function of cognition, otherwise necessary for ordinary life, becomes a fatal handicap. As a Zen saying describes it, "As soon as you call it thus and so, it has already changed." Therefore the moment-to-moment presence of mind produced by Zen training is valued by martial artists for overcoming internal complications and diversions caused by entanglement in conceptualization.

If you don't keep your mind on the sword even as you see it, and don't think about striking according to the rhythm of the opponent's sword, but move right in to take his sword the moment you see the sword raised, without keeping your mind on it at all, you can snatch away the sword about to kill you and turn it into a sword to kill your opponent instead. In Zen this is called "snatching the lance and turning it around to stab the other." This means taking your opponent's sword and killing him with it. This is what you yourself call "no sword."

In Zen technical literature, the expression "snatching the lance and turning it around to stab the other" is commonly applied to descriptions of interactive teaching wherein a question is posed to elicit a response indicative of a state of mind so that this state of mind can be addressed from a Zen point of view and its fixation dispelled. In terms of martial arts this is the equivalent of feinting in order to observe an opponent's pattern of reaction. When the tables are turned, so that a questioner is cornered with his own question, like an attacker being counterattacked with his own weapon, this is called "snatching the lance and turning it around to stab the other." Whether in Zen dialogue or in a sword duel the essential technique is to avoid having attention captured by the external form of an approach or attack, instead acting directly on its intention and taking command of its energetic charge.

Whether an opponent attacks or you attack, if you fix your mind on the attacker, the attacking sword, the pace or the rhythm, even for a moment, your own actions will be delayed, and you'll be killed.

The Diamond Cutter Scripture says, "Activate the mind without dwelling anywhere." According to legend, Hui-neng, the illustrious sixth grand master of Chinese Zen was suddenly enlightened on hearing this phrase. It has become a watchword of Zen practice ever since.

While your attention will be taken by the enemy if you put your mind on the enemy's physical presence, you shouldn't put your mind on yourself either. Even if you keep your mind focused on your own body, that should be done only as a beginner in training; your attention will be taken by the sword. If you set your mind on the rhythm, your attention will be taken by the rhythm. If you set your mind on your own sword, your attention will be taken by your sword. In any of these cases, your mind lingers, and you become an empty shell.

Zen master Hui-neng said, "When you do not dwell on the inward or the outward, coming and going freely you are able to eliminate the clinging mentality and penetrate without obstruction."

You should be aware of this. I speak in terms of analogy to Buddhism. Buddhism refers to the fixated mind as confusion, so it is called the affliction of ignorant fixation.

Zen master Hui-neng said, "If you open to understanding of the teaching of immediacy you do not cultivate practice grasping externals; you simply activate accurate perception at all times in your own mind, so afflictions and passions can never influence you." This fluid presence of mind is critical to the martial artist in the midst of action, when any lapse of attention to the immediate moment opens a fatal gap in defense.

The Immovable Wisdom of the Buddhas

Immovable does not mean inanimate; when the mind doesn't linger at all as it moves in any direction desired —left, right, all around, in all directions—that is called immovable wisdom.

Immovability does not mean immobility but imperturbability. This implies that the attention is diverted and the mind not disarrayed by external phenomena or internal states. In Zen teaching this is carefully distinguished from mental stasis, as explained by master Hakuin:

"If potential does not leave its state, it falls into an ocean of poison. This is what Buddha called the great folly of grasping realization in the absolute state. Even if you have clarified true cognition of equality you cannot activate subtle observing cognition seeing all things without impediment. Therefore, although you may be perfectly clear inside and out as long as you are hidden away in an unfrequented place where there is absolute quiet and nothing to do, yet as soon as perception touches upon different worldly situations, with all their clamor and emotion, you are powerless, beset by many miseries."

The Immovable Luminary King holds a sword in his right hand and a rope in his left hand; gritting his teeth, eyes glaring, he stands thus ready to vanquish demons who would interfere with Buddhism. He is not hidden in any land in any world. He appears to people as a protector of Buddhism, while in substance he is an embodiment of this immutable wisdom.

The Immovable Luminary King, in Japanese Fudo Myo-o, is a figure from Buddhist iconography, normally depicted standing guard outside monastery gates. The luminary kings are conceived of as demons converted to become protectors of religion, in this sense representing anger directed toward overcoming evil. Thus while the Immovable Luminary King symbolizes the imperturbable attitude of the Zen warrior, this imagery is also used as an expression of an underlying moral rationale for the way of the samurai.

Wholly ordinary people avoid opposing Buddhism out of fear, but those who are near enlightenment understand that he represents immovable wisdom. If you clear away all confusion and thus clarify immovable wisdom, then you yourself are the Immovable Luminary King; so the Immovable Luminary King is there to inform you that even demons will not be allowed to molest people who can put this state of mind into effect.

Zen teaching refers to this as a state of mind that "wind cannot penetrate, water cannot wet, fire cannot burn," a state where "demons secretly spying can find no way to see, deities offering flowers cannot discover a trail."

Therefore, the so-called Immovable Luminary King refers to the state when a person's whole mind is immovable. It is a matter of not letting oneself get upset. Not being upset is a matter of not lingering over anything. Seeing things at once without keeping your mind on them is called being unmoved.

Zen master Chinul wrote, "If you conceive aversion or attraction, this will cause you to grasp those repulsive or attractive objects. If the mind is not aroused, however, then it is unobstructed."

The reason for this is that when the mind lingers on things, all sorts of thoughts come to mind, so all sorts of movement take place in your heart. When it stops, the stationary mind does not stir even in movement.

Chinul wrote, "When the mind is aroused and exhausted along with inconstant objects, the mind on inconstant objects is opposite to the normal constant true mind."

For example, suppose ten people attack you with swords, one after another. If you parry each sword without keeping your mind on it afterward, leaving behind one to take on another, your action will not fail to deal with all ten. Even though your mind acts ten times for ten people, if you don't fix your mind on any one of them, the act of taking them on one after another will not fail. Then again, if your mind lingers in the presence of one of them, even though you may parry one man's striking sword, you will fail to act in time when the next one attacks.

Zen master Shoju Rojin was once confronted by samurai disciples who asserted that his realization might be superior to theirs in the abstract but theirs was superior to his in concrete application. The Zen master responded by challenging them to a duel facing their swords with only an iron-clad fan, parrying every blow. Stymied, the humbled samurai asked about his technique. The Zen master replied that he had no technique but clarity of the enlightened eye.

The reason why Kannon of the Thousand Hands needs a thousand hands is that if the mind is fixed on the hand holding the bow, then the other nine hundred and ninety-nine hands will be useless. By not keeping the mind on any one place, all the hands become useful. Why would Kannon need a thousand hands on one body? This image was created to show people that once immovable wisdom is activated, even if one has a thousand hands they are all useful.

Kannon is a Japanese version of the name of Avalokitesvara, one of the most important figures of mainstream Buddhist iconography representing the saving power of compassion. Because compassion implies versatility and adaptability Kannon is portrayed in many forms. The form referred to as Kannon of the Thousand Hands has a halo of hands holding all sorts of implements, representing the skillfulness of a Buddhist bodhisattva and the panoply of ways and means of educating, enlightening, and liberating people.

If you look at a tree and see only one of its red leaves, you don't see the rest of the foliage. If you look at the tree casually without setting your mind on one leaf, you see all the foliage. If your mind is taken up by one leaf, then you don't see the rest of the leaves, but if you don't set your mind on one, then you can see all hundred thousand of them. One who understands this becomes Kannon of the Thousand Hands and Thousand Eyes.

The phenomenon of being "unable to see the forest for the trees" reflects the same selective feature of brain function. While this proverb is commonly used in reference to a conceptual appreciation of a situation, in Zen and martial arts it is preeminently perceptual Zen master Bunan taught, "There is no special principle in the study of the way—it's only necessary to perceive directly."

Nonetheless, wholly ordinary people simply believe there are a thousand hands and a thousand eyes on one body, regarding this as marvelous. Then again, dilettantes with superficial knowledge repudiate it as nonsense — what is the purpose of having a thousand eyes on one body? Now when you know a little better, you respect the principle; it is neither what ordinary people believe nor what they repudiate — it is a matter of Buddhist teaching illustrating a principle through an object.

Confusion of literal and symbolic understanding is an endemic problem in organized religion, when the original inspiration has been replaced by imitation. For this reason, the revelation of symbolic meaning in scripture, the restoration of mythology to psychology was one of the specialties of the original teachings of Zen. This internalization of meaning is key to Zen expression in all the arts.

All the various Ways are like this; especially it seems, the Way of the Spirits. It is naïve to think of it literally, yet it is wrong to repudiate it; there is a principle contained therein. Even though the various Ways differ, ultimately they have a certain point.

In the context of Japanese culture, the "Way of the Spirits" refers to Shinto. This is a general term, however, and the religious phenomena to which it refers are also found in Korean, Chinese, Mongolian, Tibetan, and other cultures in which Buddhism operated. The careful distinction made here between naive literalism and abstract symbolism is characteristic of original Zen. Although mythology was retrieved from fantasy and restored to practical use on the human plane this way in time memories of events and persons on the human plane also regressed into mythology.

Now then, you should be aware that having cultivated practice from the state of the beginner's mind, when you pass the stage of immovable wisdom, you must return to the state of the beginner.

The "state of the beginner" here refers to innocence, not ineptness. The principle, applied to all arts approached in a Zen manner, is that method is eventually to be transcended once the spirit of an art is embodied. The scriptural image commonly used to illustrate this is that of a raft used to cross a river; once the other shore is reached, the raft is abandoned and the traveler goes on unencumbered. In martial arts, this level of internalization is what makes it possible to apply learning freely to real-life situations, to transcend conscious contrivance and arrive at spontaneity.

This may be expressed in terms of your martial art. A beginner knows nothing about posture or position of the sword, so there is no dwelling on body or mind; if someone attacks him, he scrambles to deal with it mindlessly. As he learns various things, however —physical posture, how to wield the sword, where to place the mind —his mind dwells on various points; if he tries to strike someone, what with one thing and another, he is exceptionally handicapped.

When he has practiced daily for months and years, finally his posture and way of wielding the sword become mindless, like he was at first when he didn't know anything and there was nothing to it. This is the frame of mind in which the beginning and the end are the same. If you count from one to ten and over again, then one and ten are next to one another. In the musical scale too, when you go from A to G from one octave to the next, then A and G are next to one another; the lowest and the highest come to resemble each other.

The return to natural unself-conscious simplicity is a hallmark of the teaching of Taoism, the precursor of Zen. Liezi, a Taoist classic, says:

"Don't dwell on yourself and things will be clear. Like water in movement, like a mirror in stillness, like an echo in response, the Way is thus in harmony with things.

"Beings deviate from the Way on their own; the Way does not deviate from beings. Those who harmonize with the Way don't even need their ears or eyes, don't use their strength or their mind. If you want to harmonize with the Way but seek it by means of looking and listening and formal knowledge, you'll never attain it.

"When you look it lies ahead, but suddenly it's behind; try to use it and it fills the universe, try to dismiss it and no one knows where it is. The mindful cannot alienate it, the mindless cannot approach it; the only ones who attain it realize it silently and actualize it naturally. Knowledge without subjectivity, capability without artifice—these are true knowledge and true capability."

Similarly, when you master Buddhism, you become like someone who knows nothing of Buddha or Dharma, with no perceptible embellishment. Therefore the affliction of ignorance in the beginning state and the immovable wisdom in the end become one; intellectualism disappears and you settle down in a state where there is no mind and no thought. Wit doesn't come out in ignorant ordinary people because they don't have any; a fully developed wit doesn't come out at all, on the other hand, because it has already gone underground. It is because of immature dilettantism that wit comes to mind, silly and ridiculous. Indeed, you must think the manners of today's clergy quite ridiculous. It is shameful.

Some Zen teachings use expressions such as "being like a complete ignoramus" to refer to transcending intellectualism. The uncomplimentary reference to contemporary clergy here alludes to those who took such teachings too literally.

There is abstract practice and concrete practice. The abstract principle is as I have explained; ultimately you don't bother with anything—it's just a matter of relinquishing the mind, as I have written. Nevertheless, if you do not do concrete practice, and just keep principles in mind, then neither your body nor your hands will work.

In terms of your martial art, concrete practice refers to the five postures and the various other things you have to learn. Even if you know the principles, you have to be able to apply them freely in fact. Yet you cannot master the postures and swordplay if you are ignorant of the ultimate point of the principles. The nonduality of fact and principle, the concrete and the abstract, must be like the wheels of a chariot.

The illusion of secondhand knowledge and the importance of actual practice are emphasized in the Zen proverb, "No one asks about the sweating horses of the past—they all want to talk about the achievement that crowns the age."

Not a Hairsbreadth Gap

This can be expressed by analogy with your martial art. Gap means the space between two things, and this expression means that not even a hair can fit in the gap. For example, when you clap your hands, the sound comes forth at once, just like that. The sound comes out with no interval between the clap and the sound, not even so much as a hairsbreadth. The sound does not come out having deliberated for a while after the hands clap—the sound comes out as the hands clap.

If your mind lingers on the sword that someone is striking with, a gap appears, and in that interval your own action is missing. If there is not so much as a hairsbreadth between an opponent's striking sword and your own action, then it is as if your opponent's sword is your own.

This state of mind is found in Zen dialogues. In Buddhism, we don't like to stop and let the mind linger on things. Therefore we call fixation an affliction. We value having no fixated mind at all, flowing freely like a ball on a rushing river, riding the flow even over obstructions.

A Zen proverb illustrates this fluidity: "Meeting situations without getting stuck, adepts have the ability to come forth with every move." Zen master Zihu said, "All things are free-flowing, untrammeled—what bondage is there, what entanglement? You create your own difficulty and ease therein. The mind source pervades the ten directions with one continuity; those of the most excellent faculties understand naturally."

The Capacity to Act in a Flash

This also refers to the aforementioned state of mind. When you strike a flint, a flash appears at once; since the sparks appear the moment you strike the flint, there is no interval or gap. This too refers to the absence of any space in which the mind can linger.

It's wrong to understand this simply in terms of speed. The point is not to let the mind come to a halt on anything. It means that the mind does not come to a halt, even quickly. Once the mind comes to a stop, your mind is taken over by someone else. If you intentionally act quickly, then the mind will still be taken away by the intention of acting quickly.

Substitution of speed for spontaneity is a familiar phenomenon in decadent Zen; Takuan's earlier uncomplimentary reference to the exercise of wit alludes to this in the context of Zen dialogue and composition. In martial arts, deliberate speed and spontaneous speed have completely different energetic results. Deliberate speed drains energy, while spontaneous speed conserves energy. Deliberate speed narrows attention by focus on intent, while spontaneous speed frees attention by unleashing unmediated response.

A reply to a poem by Saigyo by a prostitute of Eguchi says,

"If you ask about people

Who reject the world,

They're only thinking

Not to let the mind linger

On a temporary dwelling."You should understand the poem on your own, but you should realize that the thing to understand is just thinking not to let the mind linger, and this is the way to comprehend it.

Saigyo was a monk of the Tendai school of Buddhism, one of the parent schools of Zen. Takuan uses this famous poem to drive home the point that transcendence of objects is not approached by negating objects held in mind, but by ceasing to hold objects in mind.

In the Zen school, you can reply to the question "What is Buddha?" by raising your fist. In reply to the question "What is the ultimate meaning of Buddhism?" you can say, before the questioner has even finished asking, "A plum blossom," or "The cypress tree in the yard." It is not a matter of choosing a felicitous answer, it is valuing the mind that does not linger.

Simple gestures or objects used to answer Zen questions are referred to as points of entry or access, implying that the gesture or object itself is not the answer, but the greater whole of which the gesture or object is a part, including the very experience of being, and the experience of experience itself Taken out of context, Takuan's presentation here would seem perilously close to approval of the arbitrary answer syndrome characteristic of artificial spontaneity cultivated in imitation Zen cults and denounced by Zen masters. The principle of not lingering, however, is not linear but spatial, a way of seeing part and whole at once. The Zen classic Blue Cliff Record says, "A device, a perspective, a word, a statement, temporarily intended to provide a point of access, is still gouging a wound in healthy flesh — it can become an object of fixation. The great function appears without abiding by fixed principles, in order that you may realize that there is something transcendental that covers heaven and earth yet cannot be grasped."

The mind that does not linger is not affected by sense data. The essence of this unaffected mind is celebrated as Spirit, honored as Buddha, and referred to as the Zen mind or the ultimate meaning. What you say after thinking about it may be eloquent, but it is still an affliction of a state of fixation.

When we speak of the capacity to act in a flash, that refers to lightning-like speed. For example, when you call someone by name, an immediate response is called immovable wisdom. When someone is called by name and then wonders what for, the mind subsequently wondering why is afflicted by fixation. The mind that comes to a halt and is stirred and confused by things is that of an ordinary person afflicted by fixation.

Again, answering at once when called is the wisdom of the Buddhas. Buddhas and ordinary people are not two different things; Spirit and humanity are not two different things. Conformity to this mind is called Spirit, and also Buddha. Although there are many Ways, such as the Spirit Way, Poetry, and Confucianism, all of them refer to the illumination of this one mind.

While it was normal for Buddhists, particularly Zen Buddhists, to acknowledge the unity of the noumenal ground of all arts, sciences, and religions, in practice the unity of the paths often remained rhetorical The association of Zen and Confucianism was already established in China before Zen was imported to Japan, but was not much emphasized by Japanese Zen teachers until the seventeenth century when the military government of Japan sought totalitarian control over every organ of culture. Chinese Confucianism, moreover, was more highly influenced by Zen than was Japanese Confucianism.

The association of Buddhism and mystical Shinto goes back to the earliest centuries of Japanese Buddhist history but this too only became a standard feature of Japanese Zen Buddhist rhetoric in the seventeenth century. Poetry and Zen intermarried much earlier in Japan, but the vast literary corpus produced by the central Zen establishments, the so-called Five Mountains Literature, was considered sterile by practicing Zen masters and completely ignored by the leaders of the Zen revival of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The rhetoric Takuan is using, therefore, is not intended to refer to historical phenomena, or to sectarian beliefs, but alludes to the critical aim of Zen practice that opens access to the source of all arts and sciences.

As far as the mind can be explained in words, this one mind applies to others and self; good and bad deeds by day and by night come from accumulated habit, alienation and exile depend on personal status and condition, good and evil are both actions of the mind—but no one questions and realizes what this mind is, so everyone is deluded by the mind. It can be affirmed that there are people in the world who don't know the mind, while it seems that those who actually understand it are rarely found. And even if one has understanding and knowledge, they are difficult to put into practice.

Zen master Mazu said, "All kinds of establishments derive from one mind—you may set them up, and you may dismantle them. Both are inconceivable functions."

Being able to explain this one mind is certainly not tantamount to understanding the mind. Even if you explain water as a phenomenon, that does not slake thirst; and even if you talk about fire, your mouth doesn't heat up. You cannot know these things unless you come in contact with actual water and fire. You cannot know just by explaining books. You may talk about food, but that doesn't satisfy hunger. You cannot know just by talk. Even though Buddhism and Confucianism both talk about mind, without corresponding behavior the mind is not clearly known. People don't understand the mind within themselves unless they sincerely examine its fundament and come to realize it.

Zen teachings are for inducing firsthand experience. While many Zen masters were accomplished scholars, none of them claimed to understand Zen through formal learning alone; as a famous saying has it, "a picture of a cake can't satisfy hunger."

People who have engaged in Zen study do not have clear minds; though there are many people who engage in Zen study that doesn't matter. The states of mind of people engaged in Zen study are all bad. The way to clarify this one mind emerges from profound effort.

Takuan's opinion of contemporary Zen might be attributed to the fact that he died before the peak of the Zen revival but the masters of the revival also spoke critically of the state of Zen students and schools of their time. The capture of Zen schools by patronage and politics, combined with the systems of caste and primogeniture, populated Buddhist establishments with people uninterested in enlightenment.

Where to Set the Mind

Where to set the mind? If you set your mind on an opponent's physical actions, your mind is taken up by the opponent's physical actions. If you set your mind on an opponent's sword, your mind is taken up by the opponent's sword. If you set your mind on the intent to kill an opponent, your mind is taken up by the intent to kill the opponent. If you set your mind on your own sword, your mind is taken up by your sword. If you set your mind on the determination not to get killed, your mind is taken up by the intention not to get killed. If you set your mind on the other's stance, your mind is taken up by the other's stance. The point is that there is nowhere at all to set the mind.

Zen master Xuansha explained the mental poise of the free mind in terms of avoiding the specific drawbacks of fixation, whether concrete or abstract: "If you stir, you produce the root of birth and death; if you're still, you get drunk in the village of oblivion. If stirring and stillness are both erased, you fall into empty annihilation; if stirring and stillness are both withdrawn, you presume upon buddha-nature. Be like a dead tree or cold ashes in the face of objects and situations, while acting responsively according to the time, without losing proper balance. A mirror reflects a multitude of images without their confusing its brilliance."

Some ask, "If we let our mind go outside of ourselves at all, that fixates the mind on its object, resulting in defeat by the opponent. So we should keep the mind down below the navel, not letting it go elsewhere, then adapt to the actions of the opponent." Of course, that may be so, but from the point of view of the transcendental level of Buddhism, to keep the mind below the navel and not let it go elsewhere is on a low level, nothing transcendental; it belongs to the phase of developmental practice, the stage of practicing respectfulness. It is the stage referred to by the exhortation of Mencius to "Seek the free mind." This is not the higher transcendental level; it is the state of mind labeled respectful.

Keeping the mind below the navel is commonly associated with sitting meditation in modern Zen sects, but it is extremely rare in traditional Zen instructions. It is originally a fragment of a more complete system of energy circulation used in Taoism and esoteric Buddhism. Its mention here in the seventeenth century seems to reflect the adaptation of Zen to Bushido that took place in the middle ages; the establishment of the practice in pure Zen circles occurred a little later through the influence of the Kokurin school following Hakuin. In the latter case, the practice was introduced as a healing technique from Taoism, after Hakuin wrote of having recovered from a complete mental and physical breakdown through the use of this method. Eventually it was popularized as a standard element of sitting meditation, but it has limitations and negative side effects. These are seldom recognized in Zen —the present text is a rare exception—but widely warned of in Taoist writings.

As for the free mind, I'll write about that in another letter for your perusal.

If you keep your mind below your navel, trying to keep it from going elsewhere, your mind will be taken up by the thought of not letting it go elsewhere; the initiative to act will be missing, and you'll become exceptionally inhibited.

According to Taoist writers, excessive persistence in this exercise also inhibits internal activities, such as blood circulation, ultimately resulting in adverse effects on the body.

Some people ask, "If we are inhibited and unable to act effectively even if we keep our mind unmoving under the navel, then where in our bodies should we set the mind?"

If you set your mind in your right hand, it will be taken up by your right hand and your physical action will be defective. If you set your mind in your eyes, your mind will be taken up by your eyes and your physical action will be defective. If you set your mind on your right foot, your mind will be taken up by your right foot and your physical action will be defective. If you set your mind on any one place, wherever it may be, the activity of other parts will be defective.

So, where should one set the mind? I reply that when you don't set it anywhere, it pervades your whole body, suffusing your whole being, so when it goes into your hands, it accomplishes the function of the hands, when it enters the feet, it accomplishes the function of the feet, when it enters the eyes, it accomplishes the function of the eyes. As it suffuses wherever it enters, it accomplishes the functions of wherever it enters. If you fix one place to set the mind, it will be taken up by that one place, so functioning will be defective.

The original system containing concentration below the navel within it is for the purpose of circulation of conscious energy throughout the body This is considered a contrived method, however, and many Taoists have abandoned it in favor of the so-called uncontrived method through which energy spontaneously fills the whole body It is this latter spontaneous method that Zen master Takuan recommends.

When you think, it is taken up by thinking, so you should let your mind pervade your whole body without any more thought or discrimination, so that it is everywhere without being fixated anywhere, effectively accomplishing the functions proper to every part. That is to say that if you set your mind on one place you will become unbalanced. Being unbalanced means being lopsided. Balance is a matter of total pervasion; a balanced mind pervades the whole body with awareness, not sticking to one locus. Keeping your mind in one place while defective elsewhere is called having an unbalanced mind. Imbalance is undesirable.

This practical principle is illustrated in a famous Zen koan from the classic Blue Cliff Record utilizing the image of Kannon of the Thousand Hands, which Zen master Takuan introduced earlier.

In the Blue Cliff Record story, Younger Brother asks Older Brother, "What does the Bodhisattva of Great Compassion do with so many hands and eyes?"

Older Brother: "Like someone reaching back for the pillow at night."

Younger Brother: "I understand."

Older Brother: "How do you understand?"

Younger Brother: "All over the body are hands and eyes."

Older Brother: "You've said quite a bit, but that's only eighty percent."

Younger Brother: "What do you say?"

Older Brother: "Throughout the body are hands and eyes."

In this story the act of reaching back for the pillow at night represents situational use of capacities represented by the thousand hands and eyes of compassion. The image of hands and eyes all over the body represents the perceptive dimension of attainment; the image of hands and eyes throughout the body represents the energetic dimension of attainment. In the stage of complete mastery, energy is imbued with perception, and perception is imbued with energy; this is the level of attainment to which Zen master Takuan alludes by his emphasis on balance.

In all things, inflexibility results in imbalance, so it is undesirable on the Way If you don't think about where to set the mind, then the mind extends throughout the whole body, pervading it. It might be said that you should apply the mind to each situation according to the action of the opponent, without setting your mind on any particular point. Since it pervades the whole body, when you need your hands, you should use the mind in your hands; when you need your feet, you should use the mind in your feet. If you set it in one fixed place, then as you try to withdraw it from where you've set it in order to use it elsewhere, it halts there and so its function is defective.

If you try to keep your mind like a tethered cat, determined not to let it go anywhere else, keeping it on your own body, then the mind is taken up by your body. If you leave it be inside your body, it won't go anywhere else.

Effort to avoid halting in one place is all practice. Not letting the mind come to a halt anywhere is the eye, the essential point. If you don't set it anywhere, then it is everywhere. When you use your mind externally too, if you set the mind in one direction it will be missing in the other nine directions. If you don't set the mind in one direction, then the mind is in the ten directions!

The prototype of this teaching is in the Zen classic Record of Linji, Rinzai-roku in Japanese. This, along with the Blue Cliff Record, was one of the main texts of the Rinzai school of Zen to which Takuan belonged. According to the classic, Zen master Linji said, "The reality of mind has no form but pervades the ten directions. In the eyes it is called seeing, in the ears it is called hearing, in the nose it smells, in the mouth it speaks, in the hands it grips, in the feet it steps. Basically it is a single spiritual light, differentiated into a sixfold combination. Once the whole mind is as nothing, you are liberated wherever you are." Also, in a similar vein, the teaching illustrates the practice: "The immediate solitary light clearly listening is unobstructed everywhere, pervading the ten directions, free in all realms, entering into the differentiations in objects without being changed." In the martial arts, this practice is applied to attainment of the ability to respond to events spontaneously as they arise, without getting trapped or thrown off balance anywhere, mentally, energetically, or physically.

The Basic Mind and the Errant Mind

The basic mind is the mind that does not stay in a particular place but pervades the whole body and whole being. The errant mind is the mind that congeals in one place brooding about something; so when the basic mind congeals, focused on one point, it becomes the so-called errant mind.

When the basic mind is lost, its function is missing here and there, so the very effort not to lose it is the basic mind.

To make an analogy, the basic mind is like water that does not stagnate anywhere, while the errant mind is like ice that cannot be used for washing your hands or your head. When you melt ice into water so that it flows freely, then you can use it to wash your hands or feet or anything else.

When your mind congeals in one place, resting on one thing, it is like ice that cannot be used freely because it is solid—you can't wash your hands and feet with ice. Melting the mind to use it throughout the body like water, you can apply it wherever you wish. This is called the basic mind.

In terms of pure Zen, when the mind is trained to focus exclusively on specific objects and habituated to operating only in preconceived patterns, these objects and patterns become prisons of potential Applied to the context of martial arts, this means that when the mind is frozen by fixation, instinctive response is inhibited. This causes energy to stagnate, so that it cannot be accessed freely and released instantly.

The Minding Mind and the Unminding Mind

The so-called minding mind is the same thing as the errant mind. The minding mind keeps thinking about something in particular, whatever it may be. When there is something on your mind, conceptual thought arises, so it is called the minding mind.

The unminding mind is the same thing as the aforementioned basic mind; it is the mind without any stiffness or fixation, the mind as it is without any conceptualization or thought. The mind that pervades the whole body and suffuses the whole being is called the unminding mind. It is the mind not set anywhere. It is not like stone or wood —not lingering anywhere is called unminding.

When it lingers, there is something on the mind; when it doesn't linger anywhere, there is nothing on the mind. Having nothing in mind is called the unminding mind; it is also called having no mind and no thoughts. When this unminding has effectively become mind, it does not stay on anything and does not miss anything. Like a channel filled with water, it is in the body and comes out when there is a need. The mind that fixates somewhere and lingers does not work freely.

A wheel turns because it is not fixed. If it were stuck in one place, it wouldn't turn. The mind too does not work when it is fixated in one place. If there is something on your mind you are thinking about, you can't hear what people say even if you are listening to them talk. That is because your mind is fixated on what you are thinking about.

With your mind on whatever you are thinking about, it inclines in one direction; when it inclines in one direction, you don't hear things even though you listen, and you don't see even when you look. This is because there is something on your mind. Having something on your mind means there is something you are thinking about. If you get rid of that thing on your mind, then the mind is unminding and only works when there is a need, fulfilling that need.

The idea of getting rid of whatever is on your mind also becomes something on your mind. If you don't think about it, it disappears of itself, and you naturally become unminding. Persist in this, and before you realize it you will spontaneously become that way; if you try to accomplish it in a hurry, you won't get there. An ancient verse says, "Intending not to think is still thinking of something; do you intend not to think you won't think?"

One of the oldest Zen classics, Song of the Trusting Heart, says, "If you stop movement to return to stillness, stopping makes even more movement: as long as you remain in dual extremes, how can you know they're of one kind? If you don't know they're of one kind, you'll lose efficacy in both domains."

The classic Rinzai-roku says, "The ground of mind can enter into the ordinary and the sacred, the pure and the polluted, the absolute and the conventional, without being absolute or conventional ordinary or sacred, yet able to give names to all that is absolute, conventional ordinary, or sacred. One who has realized this cannot be labeled by the absolute or the conventional, by the ordinary or the sacred. If you can grasp it, then use it, without labeling it any more. This is called the mystic teaching."

In the context of martial arts, to be unminding, or having nothing on one's mind, is critical to liberation of both attention and energy from fixation and distraction to immediacy, openness, and fluidity.

Tossing a Gourd on Water—Push It Down and It Turns Over

If you toss a gourd on water and press on it, it bobs away—whatever you do, it won't stay in one place. The mind of a realized person does not rest on anything at all—it is like pushing down a gourd on the water.

The classical Zen master Yantou coined this image of Zen experience in action:

"This is like a gourd floating on water—can anyone keep it down? It is ever-present, flowing ceaselessly, independent and free —there has never been any doctrine that could encompass it, never any doctrine that could be its equivalent. It immediately appears on stimulus, turns freely on contact, encompassing sound and form. In extension it flows everywhere, without inhibition, always manifest before the eyes. How could this be a state of immobility? Go out, and nothing is not it; go in, and everything returns to the source."

Activate the Mind without Dwelling Anywhere

Whatever you do, if the thought of doing it arises, the mind rests on the thing to do. That being so, the point of this saying is to activate the mind without coming to a halt anywhere. If the mind is not activated where it is to be activated, action isn't initiated; if it is, the mind halts there. Activating the mind to do a task without halting is expertise in all fields.

The instruction to "activate the mind without dwelling anywhere" comes from the Diamond Cutter Scripture, as mentioned before. This text was commonly recited in Japanese Zen schools. A commentary attributed to Huineng, the sixth grand master of Zen, says:

"When your intrinsic nature always produces insightful wisdom, you act with an impartial, kind, and compassionate mind, and respect all people; this is the pure mind of a practitioner. If you do not purify your own mind but get obsessed with a pure state, your mind dwells on something —this is attachment to an image of a phenomenon. If you fixate on forms when you see forms, and activate your mind dwelling on form, then you are a deluded person. If you are detached from forms even as you see forms, and activate the mind without dwelling on forms, then you are an enlightened person. When you activate the mind dwelling on forms, it is like clouds covering the sky; when you activate the mind without dwelling on forms, then you are an enlightened person."

A clinging state of mind arises from that halting mind; routine habit too comes from there, so this halting mind becomes the yoke of life and death. Seeing the flowers and foliage, even as the mind seeing the flowers and foliage is activated, it does not halt there—that's the point A poem by Ji-en says, "Fragrant as flowers at the brushwood door may be, I have already seen it—what a disappointing world!" In other words, "whereas the flowers are fragrant without minding, the world I have observed with my mind on the flowers and the mindfulness of myself having been affected by it are disappointing."

The poem by Ji-en (1155-1225), a high priest of the Tendai sect of Buddhism, evokes the Four-Part contemplation of Buddhist Yoga, in which experience is observed in four parts —the perceiver, the perceived, the self-witness, and the witness of the self-witness. This is used as a framework of introspective exercise to examine the relationship between objectivity and subjectivity and the internal contradictions in consciousness.

This means that in seeing and hearing, not fixating the mind on one point is considered the ultimate attainment. To the extent that respectful means focusing on one point without wandering off, you set your mind on one point and don't let it go anywhere else; even if you subsequently withdraw and cut it off, not letting the mind go to the cutting off is the essential thing.

As noted earlier, "respectfulness," or "seriousness," are neo-Confucian terms used as an equivalent of the Buddhist exercise of focusing the mind on one point. Because this is a preliminary exercise, and keeping the mind on one point inhibits free function, in Zen and martial arts it is essential to get beyond this stage. Even so, if the mind is then focused on cutting off one-pointed focus, that intent and effort also trap the mind. Thus the Zen master says it is essential not to let the mind fixate on cutting off.

Respect is particularly essential in the context of following directions, such as from a leader or superior. There is such a thing as respect in Buddhism too. We refer to ringing the bell of respectful announcement, where we ring a bell three times, join our palms, and speak respectfully. Intoning the name of Buddha first is this attitude of respectful speech; "focusing on one thing without wandering off" and "single-minded without being distracted" have the same meaning.

The neo-Confucian schools developed in Song Dynasty China in response to the overwhelming influence of Zen were imported to Japan in the middle ages, but did not assume intellectual orthodoxy until the final feudal period, which lasted from the early seventeenth until the mid-nineteenth centuries. All of the original founders of the Noumenal school of Confucianism in China studied with Zen masters, and their teachings are heavily influenced by Zen. In Japan, this variety of neo-Confucianism was imbedded within the intellectual element of Zen Buddhism until the seventeenth century, when it was laicized and it assumed independent status in the ideological and educational structure of the Japanese state.

Even so, in Buddhism the attitude of respect is not the ultimate goal; it is a method of practical learning to stabilize the mind and not let it be scattered. When you have practiced this for a long time, your mind goes freely wherever you send it. The aforementioned stage where you "activate the mind without dwelling anywhere" is the transcendental goal. The attitude of respect is the stage where you keep the mind from going anywhere else, assuming it will scatter if you let it, relentlessly keeping the mind under control. This is just a temporary task of keeping the mind from scattering; if you go on like this all the time, you become inhibited.

One of the hallmarks of original Zen is distinguishing means and end, relinquishing the means when the end is reached. This is also rooted in the teachings of the Diamond Cutter Scripture: "You should not grasp the teaching, and should not grasp anything contrary to the teaching. In this sense the Buddha always says you know that Buddha's teaching is like a raft—even the teaching is to be abandoned, let alone what is contrary to the teaching."

Suppose, for example, that you have a captive bird; as long as you have to keep your cat on a leash, it isn't tame. If you keep your mind inhibited like a cat on a leash, you won't be able to function as you wish. If you first train the cat so that it can live together with the bird and not hunt it even if you let it free to go wherever it wants, that is the sense of activating the mind without dwelling on anything. It is a matter of letting your mind go as you would free the cat, employing the mind in such a way that even if it goes wherever it wants the mind does not halt.

The influential Zen master Dahui wrote against crude inhibitory methods of mind training, explaining that trying to suppress thought to keep the mind still and quiet is like placing a rock on grass; once the rock is lifted, the grass regrows.

Speaking in terms of your martial art, kill without keeping your mind on your hands gripping your sword, striking forgetful of all strokes, and not setting your mind on the person. Realizing that the other person is void, your self is void too, and the hand that strikes and the sword that strikes are both empty as well, you shouldn't have your attention taken by the void!

This Zen pivot is illustrated in a famous koan registered in the classic Book of Serenity: a seeker asked a master, "When not a single thing is brought, then what?" The master said, "Put it down." The seeker asked, "If I don't bring even a single thing, what should I put down?" The master said, "Then carry it out"

When Zen Master Mugaku of Kamakura was captured by the Mongols in China and about to be put to death, he composed a verse ending with the words "in a lightning flash it cuts the spring breeze." Thereupon, they say, the soldier threw down his sword and ran away.

What Mugaku meant was the sword was upraised in a flash, like lightning; and in that lightning flash there is no mind, no thought at all —the striking sword has no mind, the killing man has no mind, and the self being killed has no mind. The killer is void, the sword is void, and the self that is killed is void —so the attacker is not a person, the striking sword is not a sword, and as far as the self being killed is concerned, it is like cutting in a flash through the wind blowing in the spring sky.

This is the mind that doesn't stay anywhere at all. The sword certainly is not aware of cutting through the wind!

Zen Master Mugaku (Wuxue 1226-1286) was a Chinese monk invited to Japan in 1280 by Hojo Tokimune, the eighth regent of the Kamakura Shogunate. Tokimune was responsible for dismissing the ambassador of the Mongol Khan, who responded by launching a fleet to invade Japan. Mugaku was appointed Founder of the still famous Engakuji monastery in Kamakura, the headquarters of the first military government of Japan.

Mugaku is said to have experienced his first Zen awakening at the age of twelve, when he overheard a monk reciting the lines, "Bamboo shadows sweep the stairs without any dust being stirred; moonlight penetrates the depths of the pond without leaving traces in the water." These phrases represent the Mahayana Buddhist ideal of transcending the world in its very midst. In the context of martial arts, this means maintaining coolness, detachment, presence of mind, and objectivity even in the heat of combat.

The story of Mugaku's feat of "winning without fighting" is also cited to illustrate this ideal capacity of calm in the midst of a storm. Having fled invading Mongol armies in 1275, Mugaku was finally surrounded by advancing Mongol troops the next year. According to the story, he alone remained in the monastery where he had been staying, sitting in the communal hall, when all the other monks had disappeared. Threatened with a sword to his neck, the Zen master showed no sign of fear; instead, he extemporized,

"There's no place in the universe for a solitary walking stick;

Happily, I've found personality is void, and so are things.

Greetings to the Mongolian sword—

In a lightning flash it cuts the spring breeze."

The Mongol warriors were so impressed, it is said, that they apologized and left

It is also said that Mugaku predicted the Mongolian invasion of Japan, but assured Tokimune that it would be unsuccessful. While extrasensory capacities are sometimes admitted of Zen masters, these predictions, which proved accurate, could have also been derived from knowledge of conditions on the continent and over the Sea of Japan, knowledge that had been accumulating for several generations among the Zen pilgrims traveling between Japan and China.

Expertise is doing everything entirely forgetful of your mind this way When you dance, you brandish a fan as you step; if you conceive the intention to move your hands and feet skillfully to dance well, unable to forget it entirely, you cannot be called expert. As long as your mind is fixed on your hands and feet, the performance won't be entertaining. Everything you do without complete abandonment of mind is lousy.

Like Zen archery as noted earlier, the underlying "unminding" principle of Zen and the ways has its direct Taoist precursor in a story found in the classic Liezi:

"Zhao Xiangzi led a party of a hundred thousand hunting in Zhongshan, trampling the growth, burning the woods, fanning the flames for miles. A man emerged from a rock wall and bobbed up and down with the smoke. Everyone thought it was an apparition. Then when the fire had passed, he ambled out as if he hadn't been through anything at all.

"Xiangzi thought this strange, and kept him for observation. His form and features were those of a human, his breathing and his voice were those of a human. 'How did you stay inside the rock?' he asked; 'How did you go into the fire?'

"That man said, 'What is it you are calling "rock"? What is it you are calling "fire"?'

"Xiangzi said, 'What you just came out of is rock; what you just walked on was fire.'

"The man said, 'I didn't know.'

"When the Marquis Wen of Wei heard about this, he asked Zixia, 'What kind of man is that?'

"Zixia said, 'According to what I heard from Confucius, harmony means universal assimilation to things; then things cannot cause injury or obstruction, and it is possible even to go through metal and stone, and walk on water and fire.'

"Marquis Wen said, 'Why don't you do it?'

"Zixia said, 'I am as yet unable to clear my mind of intellection. Even so, I have time to try to talk about it.'

"Marquis Wen asked, 'Why didn't Confucius do it?'

"Zixia said, 'Confucius was one of those who was able to do it yet was able to not do it.'

"Marquis Wen was delighted."

Don't Let the Mind Go

This is a saying of the philosopher Mencius. The idea is to find the mind gone astray and return it to oneself. The point is that the mind is the master of the body but when the mind has run off into unwholesome paths, why not find it and bring it back, just as one might go find a dog, cat, or hen that has wandered away and bring it back home.

Of course, this is the obvious meaning. Nevertheless, the scholar Shao Kangjie said, "The mind should be released," changing it right around. The idea expressed here is that if you keep the mind confined you get tired and, like a cat, you can't function; so let your mind go, using it skillfully in such a way as not to fixate mentally on things and not be affected by them.

When the mind is affected by and fixated on things, and it is therefore said to avoid being affected or fixated, to return the mind to oneself, that is the stage of beginners' practice. Be like a lotus unstained by the mud—being in the mud doesn't matter. Make your mind like a highly polished crystal that isn't affected even in the mud, letting it go wherever it will. If you restrain your mind, you'll be inhibited. You may control your mind, but that's a task for the beginner, you know. If you spend your whole life on that, you'll never reach the higher stage but wind up at a lower stage.

During the phase of practicing, it is good to keep the attitude of not letting the mind go, as Mencius said. When you reach the consummation, it is as Shao Kangjie said—the mind must be released.

There is an expression "see the released mind" in the sayings of Chan Master Zhongfeng. This means the same thing as Shao Kangjie's "the mind must be released." It means that you should seek the freed mind and not keep it on one point

The expression "fully unregressing" is also from Zhongfeng. It means keeping the mind unchanging without regression. It means that even if people succeed once or twice, they should still continue to maintain a mind that eventually never regresses.

Mencius (372-289 BCE) was a Confucian scholar, but parts of his work were also valued by Taoists and Buddhists. In Japan, the book of Mencius was one of four Confucian classics constituting a common primary curriculum. Shao Kangjie (1011-1077), an expert in the I Ching, was one of the founding scholars of the neo-Confucian movement of Song Dynasty China, which was highly influenced by Zen and known as noumenalism, idealism, or the study of inner design. Zhongfeng (1263-1323) was one of the last distinguished Zen masters of China to become known in Japan. His teaching emphasizes intense concentration, particularly with the use of sayings or phrases such as noted here in Takuan's treatment of meditation in a Zen-Confucian mode.

Tossing a Ball on the Water,

Not Stopping Moment to MomentIf you throw a ball onto a rushing stream, it will ride the waves unstopping.

This image comes from the Zen classic The Blue Cliff Record: A student asked a teacher, "Does a newborn infant also have six consciousnesses?" The teacher said, "A ball tossed on rushing water." The student asked another teacher the meaning of tossing a ball on swiftly flowing water; the teacher said, "Moment-to-moment nonstop flow." The term "six consciousnesses" refers to the elementary sense consciousnesses—seeing, hearing, and so on—plus cognitive consciousness. Some commentators read "sixth consciousness," which refers specifically to cognitive consciousness. A verse on this anecdote says, "A ball tossed on boundless rushing water—it doesn't stay where it lands; who can watch?" The newborn baby stands for presence of mind in the moment, referred to in Zen terminology as "mirror-like consciousness." A prose comment explains, "The moment is fleeting as a lightning flash." In the context of martial arts, this ongoing presence of mind is the basis of instantaneous perception and reaction in the midst of rapid and unpredictable change.

Before and After Cut Off

If you don't give up a previous state of mind and also leave a present state of mind for the future, that is bad. The idea here is to sever the past from the present. This is called cutting off the connection between before and after. It means not stopping the mind.

"Cutting off the connection between before and after" is a technical expression for the basic Zen experience of presence in the moment. When attention lingers on what has already past or carries what it clings to into the future, awareness of the ongoing present is compromised by this artificial continuity. In energetic terms, when attention is pulled into the past or pushed into the future, energy is drained by tension in the gap between awareness and immediate actuality. Therefore in martial arts the connection between past and present is broken to keep freeing attention and energy in the ongoing present.

Advice to Yagyu Munenori

I understand you seek my critical advice on matters of concern to you. I don't know how you will like my ideas, but I will take the chance to write you so you might read them.

You are a master of martial arts without equal in the past or the present. Because of this your official rank, your salary, and your reputation are all excellent. You should think only of gratitude and loyalty day and night, never even dreaming of forgetting this immense favor.

Loyalty means first of all balancing your own mind and governing yourself, having no duplicity in your relation to your ruler, not being resentful or blaming others, going to work every day diligently, being filial to your parents at home, being faithful in marriage, observing proper courtesies and duties, not falling in love with concubines, giving up addiction to sex, acting properly with dignity in the company of parents, not separating yourself from employees by personal interests, employing good people and allowing them access to you so they can point out where you have fallen short, administering national policy correctly, keeping corrupt people away—when you act thus, good people advance day by day, while corrupt people are spontaneously reformed by their employer's desire for good.

When rulers and ministers, superiors and subordinates are thus good people, not greedy or extravagant, the country waxes wealthy, the people have plenty and are content, and children are close to their parents, the country will naturally be peaceful. This is the beginning of loyalty.

When you employ seasoned and loyal warriors like this for official occasions and duties, you can direct even a thousand or ten thousand men at will. Just as the thousand hands of Kannon are all useful as long as the mind is balanced, as mentioned before, if the heart of your martial art is balanced, the activity of your mind is free, as if you could subdue thousands of enemies with one sword. Is this not great loyalty?

When the mind is balanced, it is not something others know from outside. Good and bad both come from the emergence of thought. If you think about the root of good and bad, and do good while refraining from bad, your heart will naturally be honest. If you know something is bad yet don't stop it, that is because there is something wrong with your predilections.

For example, you may like sex, but are you going to make it into an overindulgent obsession? When some sort of predilection works on your mind, even if there are good people you won't like them and won't employ their good offices. Even if people are ignoramuses, on the other hand, once you like them you'll promote them; so even if there are good people, as long as you don't employ them it's as if there were no good people at all. Then no matter how many thousands of people are available, there will be no one of use to the leadership when the time comes.

The corrupt among the ignorant youths who have come into favor for a time have always had perverted minds, so they have never entertained a single thought of sacrificing their lives in an emergency. I have never heard of anyone in history whose mind is corrupt doing any good for his government. I am very distressed by reports that this kind of thing is also happening in your setting up your disciples. All of them are infected by this illness on account of a bit of luck, not knowing that they're falling into evil. They may think no one knows, denying that the subtle will come to light, but if they know it in their own hearts, then heaven, earth, ghosts, spirits, and the people all know it. Isn't this a dangerous way to defend the country? That's why I think it is serious disloyalty.

For example, no matter how ardently you yourself want to be loyal to the leadership, if the members of the whole family are not in harmony, and the people of Yagyu Valley Village rebel, everything will go awry.

They say that if you want to know people's merits and faults, you can tell by the help they employ and the friends with whom they associate. If the leader is good, the members of the cabinet are all good people. If the leader is not right, his cabinet and friends are all wrong. Then they disregard the populace and look down on other countries.

This is what is meant by the saying that people will feel friendly toward you if you are good. It is said that a country should consider good people a treasure. Recognizing this sincerely, if you get rid of subjective injustice in your knowledge of others, making it a priority to avoid petty people and take to the wise, the government of the country will improve and you can be the most loyal of ministers.

Regarding the behavior of your son, in particular, if the parent's own conduct is not correct, it is contradictory to censure the wrongdoing of the child. Straighten yourself first, and then if there is any further controversy, be correct yourself and your younger son will also straighten out by following the example of his older brother. Then father and sons will all be good. That will be auspicious.

It is said that taking and leaving should be done justly. Now that you are a favored member of the cabinet, you should never accept bribes from the warlords, forgetting justice for greed.

You like to dance, and take pride in your ability. You are pressed to come forward before the assembly of warlords and urged to dance. I think this is completely unhealthy. I hear you say the shogun's singing is like the monkey music of farcical drama. And I hear you intercede strongly with the shogun on behalf of warlords who treat you well. Shouldn't you think this over carefully? A poem says, "Since it is the mind that misleads the mind, don't leave the mind to the mind."

Takuan was known for fearlessness in his dealings with worldly powers, and this is reflected in his forthright advice to Yagyu Munenori, who was by then sword master to the shogun and chief of the shogun's secret police. Takuan was the Zen teacher of an emperor, shogun, and a number of feudal lords, but he also refused the patronage of certain powerful warlords and retired from the abbacy of the highest ranked Zen monastery in Japan just three days after his debut. After the military government imposed its own regulations on the Zen orders, Takuan was sent into exile for four years for criticizing these rules as inconsistent with the reality of Zen.

TAI-A KI: NOTES ON THE PEERLESS SWORD

By Zen Master Takuan (1573-1645)It seems that the art of war is not a contest for supremacy, and not a matter of relative strength. Not taking a step forward, not taking a step backward, I am not seen by opponents, I do not see opposition. Penetrating the place where heaven and earth have not divided and yin and yang do not reach, directness will attain success.

"I am not seen by opponents" refers to the true self, not to self in contrast to others. The self in contrast to others is visible to people, but people seldom see the true self. That is why "I am not seen by opponents."

"I do not see opposition" means having no notion of self in contrast to others, so one does not see the martial art of an opponent's personal self. But not seeing opposition does not mean that one does not see the opponent before one's eyes; subtlety is to see without seeing.

The true self is the self that is prior to the division of heaven and earth, before your parents conceived and gave birth. This self is the self that is in all animate things, birds and beasts, grasses and trees. This is what is called buddha-nature.

Therefore this self is self that has no shadow or form, no birth or death. It is not the self that is seen by the present physical eye. Only enlightened people can see it. Those who have seen it are called people who have seen nature and realized buddhahood.

In ancient times the Buddha went into the Himalaya mountains and attained enlightenment after six years of hardship. This was awakening to the true self. This is not something that ordinary people with no power of faith can realize in three to five years.

People studying the path spend ten to twenty years faithfully calling on teachers, without slacking off at all, undeterred by hardship and toil, like parents who've lost their children, never retreating from their determination, pondering profoundly, seeking intently, finally to reach the point where even notions of Buddha and Dharma are all gone; then they spontaneously see this.

"Penetrating the place where heaven and earth have not divided and yin and yang do not reach, directness will attain success" means to focus on the point where heaven and earth are as yet undivided, where neither dark nor light reach, and see directly without constructing opinions or interpretations; then you will have great success.

This introductory passage illustrates essential tactics on two levels. Externally it presents the appearance of a philosophical or metaphysical front, which conceals a hidden maneuver; as such, it is an illustration of the essential design of tactical deception. On the inward plane, the passage contains directions to a state of inaccessibility essential to both Zen and martial arts. Removing fixation of attention from the person frees it for sensing of energetic movement, thus enabling the martial artist to respond to opponents' moves more fluidly and spontaneously than possible through the medium of cognitive consciousness. In energetic terms, this implies retrieving energy from attachment and dissipation in objects conceived as such, be it an opponent, oneself, or weapons, maintaining awareness of these things in the mirroring state of immediate open awareness rather than discrete units of attention. Energy thus conserved is then sunk into a subliminal sense deep inside the energetic body, where it can detect external pressures without being tapped and drained.

Adepts do not use the sword to kill people; they use the sword to let people live. When it is necessary to kill, they kill; when it is necessary to let live, they let live. Killing is the samadhi of killing, letting live is the samadhi of letting live. They can see right and wrong without seeing right and wrong; they can discriminate without discriminating. They walk on water as on land, walk on land as on water. Whoever attains this freedom is invincible against anyone on earth and is utterly peerless.

The moral basis of the science of martial arts is derived from Taoism. The Te-Tao Ching says, "Good warriors are not militaristic, good fighters don't get angry, and those who are good at defeating opponents don't get caught up in it" The same classic says, "If you go into battle with kindness, then you will prevail; if you use it for defense, then you will be secure."