ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

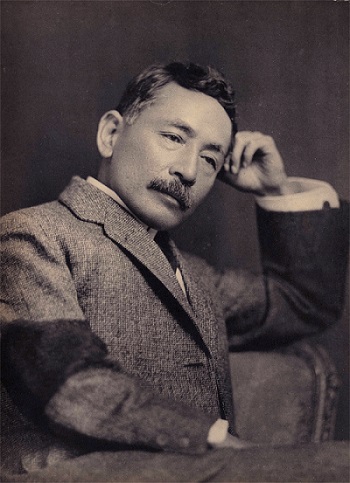

夏目漱石 Natsume Sōseki (1867-1916)

Tartalom |

Contents |

|

Dr. Erdős György: Nacume Szószeki Nacume Szószeki haikui

夢十夜 Yumejūya 門 Mon

吾輩は猫である Wagahai wa neko de aru 坊っちゃん Botchan 自轉車日記 Jitensha nikki Vihar Judit: „Kérem üljön fel egy biciklire” Czifra Adrienn: „Életem legboldogtalanabb két éve” – Hogyan jelennek meg Natsume Sōseki londoni tanulmányútjával kapcsolatos érzelmei műveiben? |

Natsume Sōseki (Encyclopaedia Britannica) PDF: Zen Haiku: Poems and Letters of Natsume Sōseki Poem in Chinese (漢詩 kanshi) Natsume Sōseki and The Gate PDF: The Pursuit of the Dao: Natsume Sōseki and His Kanshi of 1916

Haiku of Natsume Sōseki (DOC)

PDF: La porte

|

Nacume Szószeki (japánul: 夏目漱石, Hepburn-átírással: Natsume Sōseki), eredetileg Nacume Kinnoszuke (夏目 金之助 Edo, 1867. február 9. – Tokió, 1916. december 9.), a Meidzsi-korszak legelsőnek tekintett regényírója (Nagai Kafúval együtt), munkásságának köszönhető a modern realista regény meggyökerezése Japánban. Legismertebb regénye a Kokoro és a Macska vagyok. Angol irodalommal is foglalkozott, ezenkívül haikukat, kínai verseket és tündérmeséket is írt. 1984 és 2004 között az ő portréja díszítette az 1000 jenes bankjegyeket.

Szószeki 1888-ban iratkozott be a tokiói Császári Egyetem előkészítő tanfolyamára, majd 1890-től angol nyelvet és irodalmat hallgatott. Egyetemi évei alatt jól megtanult angolul, alaposan megismerte az angol – és általában a nyugati – irodalmat. A tokiói egyetemen töltött évei jelentősen befolyásolták írói fejlődését. Itt ismerkedett meg Maszaoka Sikivel (1867–1902), a fiatal írókat maga köré tömörítő tehetséges, új utakat kereső költővel.

1893-ban kapta meg tanári oklevelét, nem sokkal később Kumamotóba került gimnáziumi tanárnak. 1900-ban londoni tanulmányútra ment: két és fél évet töltött ott, ám nem tudta megszokni a nyugati életformát, nagyon zárkózottan élt. Igyekezett minél több anyagot gyűjteni Az irodalomról c. művéhez. Londonban töltött éveiről levelekben számolt be. 1903-ban tért haza, a tokiói egyetemen az angol irodalom tanárának nevezték ki. 1904-ben kezdődött írói pályafutása, ekkor kezdte sorozatosan megjelentetni a Londoni beszámolók at. 1907-ben abbahagyta a tanítást, hogy kizárólag az írásra koncentrálhasson. 1916-ban bekövetkezett korai haláláig megfeszített ütemben dolgozott: regényeket, számos elbeszélést és kritikai cikket írt. Népszerűsége oly nagy volt a japán olvasók körében, hogy a tizenegy évet, amelyben alkotott, „Nacume-éveknek” nevezték.

A legismertebb japán írók sorába a Vagahai va neko de aru (Macska vagyok, 1905) és a Boccsan (A Kölyök, 1906) című szatirikus regényeivel emelkedett – mindkettő kora szűk látókörű nyárspolgárait és értelmiségi szélhámosait gúnyolja. Harmadik regénye, a Kuszamakura („Fűpárna”, 1906) lírai alkotás, egy festőnek egy távoli faluban tett látogatásáról szól.

1907 után született művei komor hangvételűek: fő témájuk az ember küzdelme az egyedüllét ellen. Hősei művelt középosztálybeli férfiak, akik elárulnak egy hozzájuk közel álló személyt, vagy őket árulják el, és bűntudatuk vagy kiábrándultságuk elszigeteli őket embertársaiktól. A Kódzsin („Az utazó”, 1912-13) című regényében a főhős csaknem beleőrül a magányba, a Kokoro („Szív”, 1914) főszereplője pedig öngyilkos lesz. A Meian („Félhomály”, befejezetlen) és a Mon (A kapu) című utolsó regényeiben a japán értelmiség problémáival foglalkozott. A kapu egy trilógia önmagában is megálló kötete, érett mesterségbeli tudásról tanúskodik, és bepillantást enged a század eleji Japán mindennapi életébe. A regény központi alakja hiába próbál eljutni egy zen kolostor kapujához, hogy a vallásban találjon enyhülést; kudarcélménye a frusztráció, elszigeteltség és kétségbeesés riasztó jelképe. Utolsó regénye, a Micsikusza („Út menti fű”, 1915) önéletrajzi jellegű.

(Wikipédia)

Natsume Sōseki, pseudonym of Natsume Kinnosuke (born Feb. 9, 1867, Edo [now Tokyo], Japan —died Dec. 9, 1916, Tokyo), outstanding Japanese novelist of the Meiji period and the first to ably depict the plight of the alienated modern Japanese intellectual.

Natsume took a degree in English from the University of Tokyo (1893) and taught in the provinces until 1900, when he went to England on a government scholarship. In 1903 he became lecturer in English at the University of Tokyo. His reputation was made with two very successful comic novels, Wagahai-wa neko de aru (1905–06; I Am a Cat) and Botchan (1906; Botchan: Master Darling). Both satirize contemporary philistines and intellectual mountebanks. His third book, Kusamakura (1906; The Three-Cornered World), is a lyrical tour de force about a painter's sojourn in a remote village.

After 1907, when he gave up teaching to devote himself to writing, he produced his more characteristic works, which were sombre without exception. They deal with man's effort to escape from loneliness. His typical heroes are well-educated middle-class men who have betrayed, or who have been betrayed by, someone close to them and through guilt or disillusionment have cut themselves off from other men. In Kōjin (1912–13; The Wayfarer) the hero is driven to near madness by his sense of isolation; in Kokoro (1914) the hero kills himself; and in Mon (1910; “The Gate”) the hero's inability to gain entrance to the gate of a Zen temple to seek religious solace is a frightening symbol of frustration, isolation, and helplessness. Natsume's last novel , Michikusa (1915; Grass on the Wayside), was autobiographical.

Natsume claimed that he owed little to the native literary tradition. Yet, for all their modernity, his novels have a delicate lyricism that is uniquely Japanese. It was through Natsume that the modern realistic novel, which had essentially been a foreign literary genre, took root in Japan.

(Encyclopaedia Britannica)

Poem in Chinese (漢詩

kanshi)

by Natsume Sōseki

Translated by Burton Watson

In: Japanese Literature in Chinese, Vol. 2: Poetry & Prose in Chinese by Japanese Writers of the Later Period, 1976, p. 185.

Untitled

(August 16, 1916)I have no mind to bow to the Buddha, peer into the heart;

faced with monks in a mountain temple, my thoughts race to poetry.

A hundred years, pine and cypress encircle the walls before fading;

creeper and vine in one day come clambering over the fence.

Words of doctrine—but who lights the lamp before the grotto?

Dharma hymns—what power have they to burnish the moss on the stone?

Let me ask the patched-robed monk practising his Zen:

these hill-blue mists—what surface have they for defiling dust to cling to?

Natsume Sōseki, The Gate

(門 Mon, 1910)

[During the summer of 1894 Natsume Sōseki visited the Engaku-ji Temple (円覚寺) in Kamakura and practiced Zen meditation under Soyen Shaku (1860-1919). This visit inspired the novel.]

1.

translated from the Japanese by Francis Mathy

London : Owen, 1972. (UNESCO collection of representative works. Japanese series)

2.

translated from the Japanese by William F. Sibley, introduction by Pico Iyer

New York : New York Review Books, 2012.

A humble clerk and his loving wife scrape out a quiet existence on the margins of Tokyo. Resigned, following years of exile and misfortune, to the bitter consequences of having married without their families' consent, and unable to have children of their own, Sōsuke and Oyone find the delicate equilibrium of their household upset by a new obligation to meet the educational expenses of Sōsuke's brash younger brother. While an unlikely new friendship appears to offer a way out of this bind, it also soon threatens to dredge up a past that could once again force them to flee the capital. Desperate and torn, Sōsuke finally resolves to travel to a remote Zen mountain monastery to see if perhaps there, through meditation, he can find a way out of his predicament.

This moving and deceptively simple story, a melancholy tale shot through with glimmers of joy, beauty, and gentle wit, is an understated masterpiece by the first great writer of modern Japan. At the end of his life, Natsume Sōseki declared The Gate, originally published in 1910, to be his favorite among all his novels. This new translation at last captures the original's oblique grace and also corrects numerous errors and omissions that marred the first English version.William F. Sibley (1941–2009) was an emeritus professor of East Asian Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago. A translator of Japanese fiction and nonfiction, Sibley was at work on Sōseki's First Trilogy, comprising Sanshirō (三四郎 Sanshirō, 1908), And Then (それから Sorekara, 1909), and The Gate (門 Mon, 1910), at the time of his death.

Released in 1910, The Gate is among top Japanese novelist Soseki's best-known works. A man suddenly abandons his loving wife to enter a life of contemplation in a Zen temple. He goes looking for answers but finds only more questions.

— Library Journal

Chapters 18 to 21

Translated by William F. Sibley18

WITH A letter of introduction tucked in his breast pocket, Sōsuke passed through the temple compound’s main gate. He had obtained the letter from the friend of a colleague at work. This colleague would slip a copy of Maxims for Life out of his jacket pocket and read it on the streetcar on his way to and from the office. One day when the two of them were sitting next to each other on the streetcar, Sōsuke, who was ignorant of this text, never having had the slightest interest in such writings, had asked his colleague what he was reading. The man held up the small, yellow-bound volume for Sōsuke to see and replied that it was an odd sort of book. Sōsuke inquired further about the content. Apparently struggling to find the right words for a succinct reply, the colleague had remarked, in a curiously offhand fashion, that it had something to do with the study of Zen. This remark had stuck in Sōsuke’s mind.

Several days prior to securing the letter of introduction, he had gone over to his colleague’s desk and asked him out of the blue, “Do you practice Zen yourself?”

Alarmed at the look of severe tension on Sōsuke’s face, the man responded evasively, “No, no, I just read a few things in my spare time.” Sōsuke’s jaw sagged with disappointment as he went back to his desk.

That very day on the way home, he again found himself on the streetcar with this same colleague. It appeared to have dawned on the man after his glimpse of Sōsuke’s earlier disappointment that this morning’s question had been prompted by something deeper than a wish to make conversation, and so he renewed the topic in a more sympathetic manner. He confessed that he had never actually practiced Zen himself, but said that if Sōsuke wanted to learn more, he fortunately had an acquaintance who frequently visited a temple in Kamakura, and he could arrange an introduction. Right there on the streetcar, Sōsuke wrote the acquaintance’s name and address in his date book. The very next day, carrying a note from his colleague, he made a considerable detour in order to call on the man, who was kind enough to compose on the spot the letter of introduction now lodged in his pocket.

At the office Sōsuke had asked for ten days’ sick leave. Even with Oyone he maintained the pretext of actually being sick.

“My nerves are really out of sorts,” he told her. “I’ve asked for a week or so off from work so I can go somewhere and take it easy.”

Having recently come to suspect that all was not well with her husband, she had quietly but constantly worried about him, and was privately very pleased by this uncharacteristic show of decisiveness by the normally temporizing Sōsuke. Still, she was astonished by the abruptness of it all.

“And where do you plan to go and ‘take it easy’?” she asked, wide-eyed with curiosity.

“Actually, I was thinking of Kamakura,” he replied placidly.

There being virtually no common ground between her retiring husband and the fashionable seaside town, this sudden juxtaposition of the two struck Oyone as comical, and she could not suppress a smile. “My, aren’t you the dandy,” she said. “I think you should take me with you.”

Sōsuke felt too beleaguered to appreciate his beloved wife’s humor.

“I’m not going anywhere fancy,” he said defensively. “There’s a Zen temple where they’ll put me up—I’ll stay there for a week or ten days just taking it easy and giving my mind some rest. I don’t know if this will make me feel better or not, but they say if you spend some time in a place with fresh air it can work wonders for your nerves.”

“That’s absolutely true. And you should definitely go. What I said before—I was only joking.”

Oyone felt a pang of genuine remorse for having made light of her husband’s plan. The next day, bearing his letter of introduction to the temple, he boarded the train at Shimbashi terminal.

On the envelope was written “To the Reverend Brother Gidō.”

When Sōsuke’s colleague’s friend finished writing his letter, he had made a point of explaining: “Until recently this monk served as an acolyte to the head priest, but I’ve heard that he has restored a retreat in one of the sub-temples and is now living in it. I’m not quite sure which one—when you arrive you can ask somebody—but I think that it’s called the Issōan.”

Sōsuke had thanked him, put the letter away, and then, before taking his leave, listened to the man’s explanations of such unfamiliar terms as “acolyte” and “retreat.”

Just inside the main gate, tall cryptomeria trees rose up on both sides, cutting off the open sky and abruptly casting the path into deep shadow. The moment Sōsuke entered into this gloomy atmosphere he was struck by the temple’s apartness from the everyday world. Standing there, at the entrance to the temple precincts, he felt a chill come on, not unlike that which announces the onset of a cold.

Initially he proceeded straight along the path. Buildings were scattered about on either side and ahead of him, some looking like assembly halls, others like cloisters.

He saw no one coming or going. All was scoured by age and desolate in the extreme. Stopping in his tracks in the middle of the deserted path, Sōsuke cast his gaze in all directions, wondering which way to turn and whom to ask about the whereabouts of the Reverend Gidō.

The temple compound stood in a clearing that extended some one or two hundred yards up the mountain slope and was hemmed in from behind by a wall of dark green trees. The terrain to either side of him likewise sloped sharply upward into steep hillsides, such that there was little level ground. Sōsuke spotted two or three auxiliary temples, each with its own impressive gate, rising up from stone stairways and perched at higher elevations. A good many more similar edifices, each enclosed by a hedge, were scattered across the more level portion of the compound. Sōsuke approached some of the buildings and noted, hanging from the tiled roof of each gate, a plaque bearing the name of the particular cloister or retreat.

As he walked along, stopping to read a couple of the old plaques, now stripped of their gilding, it occurred to him that it would be more efficient to concentrate on looking for the Issōan, and then, if Gidō were not to be found at this retreat, to move farther into the compound and make inquiries. Retracing his steps, he inspected each and every building and eventually came upon the Issōan at the top of a long flight of stone steps that led up to the right from just inside the main gate. The retreat, its exposed front blessed with full sun and its rear tucked cozily into a hollow at the base of the mountain that rose up behind it, appeared well designed to keep winter at bay. Entering the retreat, Sōsuke stepped into the earthen-floored kitchen, approached the shoji leading into the building proper, and called out two or three times to announce himself. No one appeared to greet him. He stood there for a while peering at the shoji, trying to make out some sign of life inside. He waited still longer, but to no avail; there was no sign, no hint of anyone. Baffled, he went back through the kitchen and out toward the gate. Just then he saw a monk climbing the stone steps, his freshly shaven head aglow with a bluish hue. His pale face was that of a young man, perhaps twenty-five years old at most. Sōsuke waited at one of the open portals of the gate and asked, “Does the Reverend Gidō reside here?”

“I am Gidō,” the young monk replied.

Sōsuke was pleasantly surprised. He removed the letter of introduction from his breast pocket and handed it to Gidō, who read it on the spot. After folding the letter up and putting it back in the envelope, he welcomed Sōsuke warmly and without further ado led him into the retreat. They deposited their clogs on the kitchen floor, opened the shoji, and stepped inside. There was a large square hearth sunk into the floor. Gidō removed the coarse, thin surplice he wore over his gray robe and hung it on a hook.

“You must be very cold,” he said, raking up pieces of hot charcoal from under a thick layer of ashes.

The monk spoke with an ease that was rare in someone so young. The quick smile that punctuated his well-modulated utterances struck Sōsuke as distinctly feminine.

Wondering what fateful episode had led the man to shave his head, Sōsuke felt a twinge of pity for this monk who comported himself with such gentility.

“It seems very quiet today,” he said. “Has everyone gone out?”

“No, it’s like this every day. I am the only one here. I don’t even bother locking up when I have an errand to do. I just leave the place open. I was out on an errand just now. That’s why I was regrettably not here to greet you when you arrived. Do please forgive me.”

Thus did Gidō offer his guest formal apology for his absence. Sōsuke realized that his arrival could only add to the considerable burden on this monk, charged as he was with looking after the large retreat all by himself, and his face betrayed some embarrassment.

“Oh, but you mustn’t be concerned on my account. It is all for the sake of the Way.”

Gidō’s words conveyed much grace. He went on to explain that at present, besides Sōsuke, there was one other layman in residence whom he had been looking after. Evidently, it had already been two years since the man first arrived at the compound. When, two or three days later, Sōsuke first encountered this layman, he turned out to be an easygoing fellow with the face of a playful arhat. At that moment he was dangling a bunch of daikon, which he presented as a special treat. He had Gidō boil and serve the large white radishes at a meal for the three of them. This layman had such a monkish look about him that, as Gidō laughingly related, he managed to insinuate himself from time to time into the clerical ranks at the ceremonial feasts offered up in the town by the faithful.

Sōsuke heard a good deal about other laymen who came to the temple for training. Among them was a seller of writing brushes and ink who, for three or four weeks at a stretch, would make his rounds on foot with a load of goods strapped on his back; when he had sold nearly all of his stock, he would return to the temple and resume his life of meditation. In due time, when the wherewithal to buy his meals was depleted, he would pack up a new supply of brushes and ink and go back on the road. These two facets of his life alternated with a certain mathematical inevitability, apparently without his ever finding it monotonous.

When Sōsuke compared the everyday lives of these people, seemingly so free from petty obsessions, with the present state of his own inner life, he was dismayed by the glaring disparity. Were they able to practice zazen in this way because they led such carefree lives? Or had their minds become carefree as a result of their practice?

He could not tell which.

“It’s certainly not a matter of being carefree,” said Gidō. “If it could all be done as a kind of pleasant pastime, we wouldn’t have all these devoted monks suffering through twenty or thirty years of wandering from one temple to another.”

The monk proceeded to offer him some basic guidelines for zazen, followed by a general description of what it was like to rack one’s brains morning, noon, and night over a koan posed by the Master, all of which was deeply unsettling for Sōsuke. Gidō then stood up and said, “Let me show you to your room.”

The monk led Sōsuke away from the hearth, across the sanctuary, and then along the veranda a few steps to some shoji that gave onto a six-mat room. At that moment Sōsuke felt for the first time how far from home his solitary journey had taken him. Yet his mind was still more agitated than it had been in the city, perhaps because of the very tranquillity of his surroundings.

After what seemed like an hour or more, he heard Gidō’s footsteps reverberating again from the direction of the sanctuary.

Kneeling deferentially at the threshold to Sōsuke’s room, the monk said, “I believe the Master is prepared to conduct an interview. Let us go now, if it’s convenient for you.”

Leaving the retreat vacant, they set out together. Proceeding up the main path a hundred yards or so farther into the compound, they came to a lotus pond on the lefthand side. With nothing growing at this chilly season the stagnant pond was murky and devoid of anything that might have conveyed a sense of purity and enlightenment.

But across the pond, a glimpse of a pavilion, ringed by a railed veranda and backing into a rocky cliff, presented a rustic scene of the sort depicted in paintings of the literati style.

“That is where the Master resides,” said Gidō, pointing up at the edifice, which appeared to be of relatively recent construction. Skirting the shore of the pond, the two of them climbed five or six flights of stone steps. At the top, with the structure’s massive roof towering directly above them, they made a sharp turn to the left. As they approached the entranceway, Gidō excused himself and made his way to the rear entrance. Presently he reemerged through the front door, ushered Sōsuke in, and led him to the room where the Master was seated.

The Master looked to be around fifty years old. His ruddy face had a healthy glow. His smooth skin and taut muscles, without a wrinkle or sag, suggested a bronze statue and made a deep impression on Sōsuke. Only his lips, which were exceedingly thick, revealed a hint of slackness. But this small detail was obliterated by a vibrancy that flashed from the Master’s eyes, the likes of which were not to be seen in any ordinary man. Encountering this look for the first time was for Sōsuke to glimpse a naked blade glinting in the dark.

“Well, it’s really all the same, wherever you begin,” said the Master as he turned toward Sōsuke. “‘Your original face prior to your parents’ birth—what is that?’

Why not mull this one over a bit?”

Sōsuke was not at all sure about the “prior to your parents’ birth” part, but concluded that, at any rate, the idea was to try to grasp the essence of what, finally, this thing called the self is. He was too ignorant of Zen even to ask for further clarification. Along with Gidō he withdrew in silence and returned to the Issōan.

Over dinner Gidō explained to Sōsuke that consultations with the Master took place once in the morning and once in the evening, and that at noon there were sessions known as the Exposition of Principles.

“It may turn out that you won’t have reached a proper understanding by the consultation time tonight,” he added solicitously, “and so perhaps I could take you to the Master tomorrow morning, or even in the evening.” Gidō then advised him that, since it would initially be difficult to remain sitting in meditation for a long stretch, it might be a good idea for Sōsuke to light an incense stick in his room, as a sort of timer to signal moments in which to take little breaks between his meditation sessions.

Incense in hand, Sōsuke passed by the sanctuary, entered the six-mat room assigned to him, and sat down on the tatami in something of a daze. He was overwhelmed by a sense of how utterly removed these so-called koan were from the reality of his present life. “Suppose I was suffering at this moment from a stomachache,” he put it to himself. “So I go off somewhere in search of relief from the pain and I’m presented with, of all things, a difficult mathematical problem, and I’m told, ‘Oh, here’s something for you to mull over.’” The situation he faced now was no different from this. Mull it over? All right, he could certainly do that, but to do it before his stomachache had let up was asking entirely too much.

Nevertheless, he’d taken a leave of absence and come all this way. And even if only out of consideration for the man who had written him the introduction, and now for this Gidō who was doing so much to look after him, he could not act rashly. He resolved to summon up whatever courage he could in his present state and face the koan head on. Sōsuke himself had absolutely no idea where such efforts might lead him or what effects they might produce deep within. Beguiled by the enticing word “satori,” he had embarked with uncharacteristic boldness on a most challenging venture. Even now he clung to the tenuous hope that his venture would succeed, that he just might be delivered from the weakness, instability, and anxiety that assailed him.

He propped up a slender incense stick in the cold ashes inside the brazier and set it to smoldering, then sat on a cushion and folded his legs, as he had been taught, into a half-lotus position. After the sun set, his room, which had not seemed particularly cold by day, suddenly turned frigid. The temperature fell low enough to send shivers up and down his spine as he sat.

Sōsuke pondered. But it was all so nebulous that he did not know whether to begin by considering the general approach to take in his thoughts or proceed directly to the concrete problem assigned to him. He began to wonder if he had not come on a wild-goose chase. He felt like someone who, having set out to lend a hand to a friend whose house has burned down, instead of consulting a map and traveling by the most direct route, gets caught up in some totally irrelevant diversion.

All manner of things drifted through his head. Some of them were clearly visible in his mind’s eye; others, amorphous, passed by like so many clouds. It was impossible to determine whence they had arisen or where they were headed. Some would fade away only to be replaced by others. This process repeated itself endlessly. The traffic coursing through the space inside his head was boundless, incalculable, inexhaustible; no command from Sōsuke could possibly put a stop to it, or even momentarily arrest it. The harder he tried to shut it off, the more copiously it poured forth.

In a panic he recalled his everyday self and looked around the room, which was lit only by a dim lamp. The incense stick propped up amid the ashes had burned down only halfway. He became aware as never before how terrifyingly time prolonged itself.

Once again Sōsuke pondered. Immediately, objects of all shapes and colors began to pass through his mind. They moved along like an army of ants, which, having passed by, was promptly followed by another. Only Sōsuke’s body remained still. His conscious being was forever on the move: an excruciating, unremitting, almost unbearable motion.

His body, rigid from the meditating, began to ache, starting with his kneecaps. His spine, which he had kept ramrod straight, began to bend forward. Sōsuke took hold of his left foot with both hands at the instep and lowered it. He got to his feet and stood aimlessly in the middle of the room. He felt the urge to open the shoji, step outside, and simply walk about in front of the gate. The night was still. It did not seem possible that anyone else was around, asleep or awake. He lost the courage to go outside. Yet the prospect of just sitting there and being tormented by demonic phantasms was terrifying.

Resolutely he propped up another stick of incense and proceeded to repeat more or less the same sequence he had gone through before. In the end he reasoned that if the main point of this was to ponder the koan in question, it could not make much difference whether he pondered while sitting or while lying down. Taking the soiled futon from where it lay folded in the corner he spread it out and burrowed under the covers. At this, worn out from his exertions, without a moment’s pause in which to ponder anything, he fell into a deep sleep.

When Sōsuke awoke the shoji near his pillow were already light, hinting at the sun’s bright rays that would soon be cast on the white paper. Naturally, at this mountain temple where by day everything was left deserted and unlocked, he had not heard any sound of the retreat being shuttered the night before. The very instant he became aware that he was not lying in his dark room at the base of the embankment below Sakai, he got up and went out to the veranda, where a giant cactus growing up to the eaves loomed before his eyes. From there he retraced yesterday’s steps, past the altar in the sanctuary and back to the anteroom with the sunken hearth, where he had first entered upon his arrival. Gidō’s surplice was hanging from the same hook as before. The monk himself was in the kitchen, crouched down in front of a stove in which he was building a fire.

“Good morning,” Gidō greeted Sōsuke cordially as soon as he saw him. “I was going to invite you along earlier, but you seemed to be sleeping so peacefully that I took the liberty of going without you.”

Sōsuke learned that the young monk had completed the first za-zen session by dawn and then returned to the retreat in order to prepare rice.

On closer inspection he noted that Gidō, as he fed kindling into the fire with his left hand, was holding up with his right a book with black binding to which he redirected his attention at every available moment. The book bore the imposing title of Hekiganroku. Sōsuke wondered to himself if, instead of getting trapped in his own random thoughts, as he had the previous night, and overtaxing his mind, it would not be a lot simpler to borrow some standard texts used in this denomination and get the gist of it by reading. But when he suggested this course to Gidō, the monk rejected it out of hand.

“Reading over texts is no good at all,” he said. “In fact, to be honest, there is no greater obstacle to the true spiritual practice than reading. Even people like me who have gotten to a certain stage—we may read Hekiganroku, but as soon as the text goes beyond our level, we don’t have a clue. And once you get into the habit of jumping to conclusions on the basis of something you’ve read, it becomes a real stumbling block when you sit down to meditate. You start imagining realms beyond the one where you belong, you eagerly wait for enlightenment, and just when you should be forging ahead with all deliberate speed, you run up against a wall. Reading things is a snare and a delusion—you really should just forget about it. If you feel you absolutely must read something, then I’d suggest a work like Incentives to Breaking Zen Barriers. It will inspire you to greater commitment. Still, it’s something you read only for the sake of reinforcing that commitment, without imagining it has anything to do with the Way.”

Sōsuke did not really understand what Gidō meant. But he was aware that standing here in front of this youthful monk with the bluish bald head made him feel like a dim-witted child. His once overweening pride had long ago been ground down into nothing—ever since the events in Kyoto. From that time on, until this day, he had accepted his ordinary lot and lived accordingly. All thought of achieving worldly distinction had been expunged from his heart. He stood before Gidō simply as the person he was. He was forced to recognize, moreover, that in this place he was no better than an infant, far weaker, still more witless, than in his ordinary life. This came as a revelation to him, one that eradicated the last vestige of his self-respect.

While Gidō extinguished the flames in the stove and waited for the rice to finish steaming, Sōsuke stepped out from the kitchen into the temple grounds and washed his face at the well. Directly ahead of him rose a tree-covered hill. At its base a small plot had been leveled for a vegetable garden. His face still dripping in the cold wind, Sōsuke made a detour to inspect the garden. Once there, he saw that a large grotto had been carved out of the bottom of the cliff. He stood there for a spell peering into its dark recesses. When he returned to the anteroom a warm fire burned in the sunken hearth and the iron kettle was on the boil.

“I prepare things on my own, you see, and breakfast tends to be late, but I’ll bring you your tray in a moment,” Gidō said apologetically. “And being way out here, I’m afraid it’s pretty poor fare we can offer you. I’ll try to make up for it by treating you to a proper bath—tomorrow, hopefully.” Sōsuke gratefully took a seat on the other side of the hearth.

Presently, breakfast over, he found himself back in his room with his attention riveted on the singular question that confronted him: What was his original face before his parents were born? Since the problem defied rational thought, however, it was impossible to begin by extrapolating from what had been given; no matter how hard he pondered he could not get a handle on it. He soon tired of pondering. It occurred to him that he really should write to Oyone to let her know he had arrived safely.

With palpable delight at this ordinary task to be done, he hastened to remove a roll of writing paper and an envelope from his satchel and began a letter to his wife. As he proceeded to write about one thing and another—how quiet it was here, to start with; how much warmer it was than in Tokyo, perhaps because the sea was so close; how fresh the air was and how nice the monk, the one he had the introduction to; how unappetizing the food; how rudimentary the bedding—he had before he knew it used up more than three feet of writing paper, at which point he lay down his brush. But of his struggle with the koan, of the pain in his knee joints from sitting in meditation, of his sense that his nervous disorder was only being made worse by all this pondering, he wrote not a single word. On the pretext of having to get the letter stamped and posted, he immediately left the temple compound. After wandering around the town some, haunted all the while by thoughts of his original face, of Oyone, and of Yasui, he returned to the retreat.

At the noon meal Sōsuke met the lay practitioner Gidō had spoken of. Every time the man passed his bowl to Gidō for more rice, he refrained from making any deferential requests and instead simply pressed his palms together in thanks and expressed his other needs with hand gestures. To receive one’s meal silently in this fashion, it was explained to Sōsuke, was in keeping with the dharma. The guiding principle here, apparently, was that to speak or make any more noise than necessary would interfere with the process of meditation. Witnessing such exemplary seriousness, he felt rather ashamed of the way he had been conducting himself since the previous evening.

After lunch, the three of them sat talking awhile. The lay practitioner told him that once, while engaged in meditation, he had fallen asleep unawares; the moment he regained consciousness he had rejoiced at his sudden enlightenment, only to realize on opening his eyes that, alas, he was his same old self. Sōsuke had to laugh. He was relieved to see that one could also approach Zen with lightheartedness of this sort. But as the three of them parted to return to their respective quarters, Gidō simply urged him on: “I’ll let you know when it’s time for dinner. Please apply yourself to your meditation until then.”

At this, Sōsuke felt a renewed sense of obligation. He returned to his room with a queasy feeling, as though he had swallowed a hard dumpling that now lodged undigested in his stomach. Again he lit a stick of incense and began his sitting. Distracted by the nagging thought that he had to equip himself with some sort of response to the koan, no matter what it was, he eventually lost all concentration and ended up simply wishing for Gidō’s early approach from the sanctuary to summon him to dinner.

Amidst all his anguish and fatigue the sun sank low in the sky. As the light reflected on the shoji slowly faded away, the air inside the temple turned chilly, from the floor upward. From early in the day no breeze had stirred in the branches. Sōsuke went out on the veranda and gazed up at the high eaves. Beyond the long row of black tiles, their front edges perfectly aligned, he watched the tranquil sky enfold the pale blue light within its depths, until both sky and light faded away.

19

“PLEASE watch your step.” Gidō led the way down the stone steps in the dark, with Sōsuke following a pace behind. Here, away from city lights, the footing by night was uncertain, and the monk carried a lantern to illuminate their one-hundred-yard passage through the compound. They reached level ground at the bottom of the stone steps, where tall trees thrust out their branches from left and right, blocking out the sky and seemingly close to grazing the tops of their heads. Dark as it was, the green of the leaves was still visible. It all but soaked into the weave of their clothing and sent a chill through Sōsuke. The lantern itself seemed to emit the same color of light and, in contrast to the mighty tree trunks that it managed to bring into outline, looked exceedingly small. The faint light it cast on the ground was no more than a few feet in diameter, a small pale gray disk bobbing along with them in the dark.

Past the lotus pond, they turned left and climbed up toward the Master’s residence; there the going became rough for Sōsuke, who was making the trek for the first time at night. At a couple of points the front edge of his clogs struck against the exposed surface of buried rocks. Gidō knew of a shortcut that, before reaching the pond, led straight to the residence, but the ground there was still rougher, and on Sōsuke’s account he had chosen the more roundabout path.

Once inside the entryway Sōsuke detected a good many clogs strewn about the dimly lit earthen floor. Bending low, he proceeded to thread his way through the footwear and stepped up into an eight-mat room. Alongside one wall six or seven men had seated themselves deferentially at right angles to the corridor leading from the entrance to the Master’s quarters. A few of them had the gleaming bald heads and black robes of monks. Most of the others were dressed as laymen, though in formal hakama. Not a word was spoken. Sōsuke stole a glance at the men only to be arrested by the severity of their faces. Their mouths were hard-set, their eyebrows closely knit in concentration. They appeared heedless of whoever was next to them and oblivious to anyone entering from the outside, no matter what manner of man he might be. With the bearing of living statues they sat utterly still in this room to which no fire brought warmth. To Sōsuke’s mind these figures added an even greater austerity to the already frigid atmosphere of the mountain temple.

After awhile the sound of footsteps filtered into the desolate silence. At first a faint echo, the tread of feet on the wooden floor grew steadily heavier as they approached the area where Sōsuke was sitting. Then, all of a sudden, the figure of a solitary monk loomed in the doorway leading to the corridor. The monk moved past Sōsuke and, without a word, exited the temple into the darkness. Just then a small bell tinkled from somewhere deep inside.

At this, one of the laymen wearing a hakama of sturdy Kokura cloth stood up from the row of men seated solemnly with Sōsuke alongside the wall; he crossed over silently to the corner of the room and sat down again, directly in front of the open doorway to the corridor. Next to where he sat, within a wooden frame about two feet tall and one foot wide, there hung a gong-shaped metal object that was, however, too thick and heavy to be an ordinary gong. It glowed a midnight blue in the scant light. The man in the hakama picked up the wooden hammer from a stand and struck the center of the gong-shaped bell twice. Then he stood up, passed through the doorway, and advanced down the corridor. Now, in a reverse of the previous pattern, as the footsteps moved deeper into the temple’s interior they grew fainter and fainter, and ultimately died out. Still seated firmly in his place, Sōsuke was inwardly shaken. He tried to picture to himself what momentous things might be happening to the man in the hakama right now. But throughout the temple confines, complete silence prevailed. Among those who sat in a row with him no one moved even a single facial muscle. Only Sōsuke’s mind stirred, with imaginings of what might be occurring in the temple’s inner recesses. All of a sudden the handbell rang again in his ears, accompanied by the sound of approaching footsteps along the length of the corridor. The man in the hakama appeared in the doorway, crossed over to the entrance without a word, and vanished into the frosty air. The man whose turn was next stood up, struck the gong-like bell as before, and marched off down the corridor. Hands planted formally on his knees, Sōsuke waited his turn.

Shortly after the second-to-last man in line before Sōsuke had gone to take his turn, a loud shout resounded from down the corridor. Because of the distance, the sound was not so loud as to strike Sōsuke’s eardrums with any great force, but it reverberated enough to bespeak a mighty upwelling of righteous indignation. The tone was so distinctive that there was only one person from whose throat it could have issued. As the very last man in front of him stood up, Sōsuke, gripped by the consciousness that his turn was next, lost most of what little composure he had left.

He had prepared a kind of response to the koan he had been assigned the other day, the best he could come up with. Still, it was exceedingly tentative and flimsy: nothing more, really, than an empty phrase concocted for the occasion, composed of words meant to convey a semblance of assurance where there was in fact none, in order to demonstrate some capacity for discernment when he found himself in the Master’s presence. Not that it occurred to Sōsuke in his wildest dreams that he would be so lucky as to escape his predicament with this pathetic, rehearsed response. Nor, of course, did he have any intention of putting something over on the Master. By this point he had become a good deal more earnest than when he first arrived. He felt quite mortified to find himself in the false position of appearing before the Master simply out of a sense of obligation, with nothing to offer but vague words that had popped into his head, as if serving someone a sketch of a rice cake instead of the real thing.

As Sōsuke struck the gong-bell in the same fashion as those before him, he was fully aware that he was not qualified to wield the same hammer as the others. He was filled with self-loathing at how he had simply gone ahead and mimicked them like a tame monkey.

Dreading in his heart his own weak self, he went through the doorway and started down the corridor. It was a long way. The rooms to his right were dark; after turning two corners, he saw lamplight coming through a shoji at the very end of the corridor. He advanced to the threshold of that room and came to a halt.

The protocol for such audiences was a triple kowtow to the Master before entering. The supplicant bowed as he would in the course of an ordinary greeting, with his forehead nearly touching the tatami, while at the same time placing his hands, palms up, at either side of the head—and then raising them a bit, up to ear level, as if reverently presenting an offering. Kneeling at the threshold, Sōsuke performed the first kowtow according to the prescribed form. From within the room came the command: “Once will suffice.” Dispensing with further protocol, he entered the room.

The only light came from a single dim lamp, so dim that one could not have read even relatively large characters by it. Sōsuke could not recall having ever seen anyone function at night with the sole aid of such paltry lamplight. Although naturally stronger than moonlight and not of such a bluish hue, it did have the lunar quality of looking as though it might vanish behind murky clouds at any moment.

In this indistinct light, four or five feet straight ahead of him, Sōsuke could make out the figure of the one whom Gidō called “Rōshi.” His face had the same cast-in-metal impassiveness and color as before. His entire body was wrapped in vestments the color of tannin or persimmon or tea. His hands and feet were out of view. He appeared in the flesh only from the neck up. His countenance, which possessed an utmost solemnity and tension that conveyed imperviousness to time, was riveting. And his head was perfectly smooth-shaven.

Seated in front of this face, the spiritless Sōsuke exhausted what he had to say in a single phrase.

The response was immediate: “You’ll have to come up with something sharper than that!” the voice boomed. “Anybody with even a bit of learning could blurt out what you just did.”

Sōsuke withdrew from the room like a dog from a house in mourning. From behind him reverberated a vehement ringing of the handbell.

20

FROM THE other side of the shoji a voice called out: “Nonaka-san, Nonaka-san.” Still half asleep, Sōsuke was sure he had answered this call; yet before uttering a response, he had in fact lost consciousness and fallen back into a deep sleep.

Later, when he awakened for a second time, he leapt to his feet in consternation. Going out on the veranda, he found Gidō clad in a gray robe, with the sleeves tied up to free his hands, energetically wiping down the floor. As he squeezed out a wet rag in his benumbed red hands, the monk said good morning to Sōsuke with his customary gentle smile. Again this morning, the first meditation long since over, he had been busy attending to his chores around the retreat. Reflecting on his indolence, staying in bed even after attempts had been made to wake him, Sōsuke felt utterly ashamed.

“I’m sorry I overslept again today,” he said, as he sidled away from the kitchen door toward the well. He drew some cold water and washed his face as quickly as possible. His beard had grown out enough for his cheeks to feel prickly to the touch, but he had no room in his head to bother about such things. He brooded ceaselessly over the contrast between Gidō and himself.

The day Sōsuke had received his letter of introduction he had been told not only what a decent man this monk was but also how advanced he was in the practice of the discipline. And yet Gidō had turned out to be as self-deprecating as some unlettered lackey. To see him like this, sleeves rolled up, scrubbing away, surely no one could imagine that he was the master of his own retreat. He looked more like some sort of temple bookkeeper or at most a postulant.

Prior to this dwarfish young man’s ordination, while still a lay practitioner, he had evidently sat in the lotus position for seven days straight without moving a muscle.

The pain in his legs was such that he could hardly stand up; eventually he could only make his way to the privy by leaning against the wall. At the time he was working as a sculptor. On the day he was enlightened into the True Nature, he had dashed up the hill behind the temple in an excess of joy and shouted out in a loud voice, “Everything on earth, plants and trees, mountains and streams, without exception they enter into Buddha-hood.” It was only then that he shaved his head.

Gidō told Sōsuke that it had been two years since he had been entrusted with this retreat but that he had yet to sleep in a proper bed with his legs stretched out comfortably. Even in winter, he said, he slept sitting up, fully clothed, leaning back against the wall. When he was still an acolyte, he added, he had even had to wash the Master’s loincloth. In those days, whenever he managed to steal some time from his chores to sit and meditate, someone would sneak up behind him and play some nasty trick, and people were always saying vicious things about him, such that during his novitiate he often found himself reproaching the ill fate that had landed him in a monastery.

“It’s only lately that things have gotten a little easier,” he said. “But I still have a long road ahead. Sticking to the practice is a tough business. If there were an easier way to go about it, I wouldn’t be so foolish as to keep slaving away like this for ten or twenty years.”

Gidō’s account left Sōsuke in a demoralized fog. Besides the frustration over his own lack of commitment and spiritual resources, there was the obvious but unanswerable question of why, if success in this arena required so much time, he had come to the temple in the first place.

“You mustn’t think that what you’re doing is a waste of time,” said Gidō. “Ten minutes of meditation yields ten minutes worth of achievement, of course, and twenty minutes of meditation doubles the merit you accrue. And once you’ve made the initial breakthrough, you can continue your practice without having to keep coming back here all the time.”

Sōsuke felt duty-bound to return to his room and meditate again.

He was greatly relieved when, while he was thus engaged, Gidō came to announce that it was time for the Exposition of Principles. There was nothing but misery in sitting here rooted to the spot, agonizing over a conundrum that was as hard to grasp as a bald man was by the hair. Rather than this, any sort of active, physical exertion was preferable, no matter how much energy it might require. He simply wanted to move about.

The location for this event was about as far from the retreat as was the Master’s temple, some one hundred yards away. They reached it by once again passing the lotus pond, then, instead of turning left, following the path straight ahead to where the building stood, its majestic roof tiles soaring among the pines high above. Gidō carried a black-bound book in his breast pocket. Sōsuke naturally had nothing to bring. He had not even known until he came here that “exposition of principles” meant something like what in school would be called a lecture.

The high-ceilinged hall was surprisingly spacious and very cold. The faded tatami blended with the ancient columns in a manner redolent of the distant past. The people seated here all appeared appropriately subdued. Although everyone had sat down wherever he pleased, in no particular order, there was no noisy conversation and not so much as a chuckle to be heard. The monks, wearing vestments of navy-blue hemp, sat in two rows facing one another, arrayed on either side of the barrelbacked officiant’s chair that was placed front and center. The chair was painted vermilion.

Presently the Master appeared. Sōsuke, who had been staring down at the tatami, had no idea when he had come in or what path he had taken to cross the room.

He only noticed the Master when his impressive figure was already perched, utterly serene, in the officiant’s chair. He then watched as a young monk standing close to the chair undid a purple silk wrapping and produced a book, which he proceeded to set down reverently on a table. Sōsuke followed the monk with his eyes as he made a deep bow and retreated.

At this point all of the monks in the congregation pressed their palms together and began to recite from The Testamentary Admonitions of Musō Kokushi. The lay congregants who were scattered about near Sōsuke all joined in at the same droning pitch. The recitation had a melody-like rhythm to it and sounded somewhere in between sutra-chanting and normal speech: “Among my students there are three grades: those who can be said to have gone the limit, who have cast off all bonds with others and have single-mindedly examined themselves—they are known as the highest grade; those whose practice of the discipline is not pure, who indulge in eclectic studies—they are termed the middle grade . . .” The passage was not very long. Sōsuke had at first not known who Musō Kokushi was, but he learned from Gidō that Musō and Daitō Kokushi were the patriarchs responsible for the resurgence of the Zen school. Gidō went on to tell him about how Daitō had been lame in one leg and unable through the years to sit in the lotus position. He was so exasperated by this failing that, shortly before he died, determined to force his body to do his bidding, he wrenched his leg until it broke and finally assumed the full lotus position, spilling enough blood in the process to soak his robe.

Presently the recitation proper began. Gidō removed the black-bound volume from his pocket, opened it, and slid it over the tatami to where Sōsuke could see the first page. The work was entitled On the Inextinguishable Light of Our School. Gidō had explained to Sōsuke when he first inquired about the book that it was an especially suitable work for him. According to the monk, it had been compiled by a disciple of the Abbot Hakuin, an eminent priest named Torei or the like, with the purpose of presenting in proper order the various stages of Zen training, from the most basic to the most advanced, along with the psychological states that accompanied each stage.

Sōsuke’s visit to the temple had come in the middle of this recitation series, and he found it difficult to absorb everything that was said. The speaker was articulate, however, and Sōsuke, as he listened in passive silence, found many things of interest. Clearly with the aim of spurring on earnest novices, the recitations regularly included anecdotes about Zen adepts who had struggled mightily along the way, thus lending some spice to these expositions.

Today’s session had proceeded in this fashion up to a certain point when, changing his tone abruptly, the Master launched into a denunciation of those who manifested a lack of sincere commitment in the course of his individual interviews.

“Just recently,” he said, “there was someone who actually complained in my presence that even now, in this place, he was under the sway of illusion.”

Sōsuke shuddered in spite of himself. For he in fact was the one who had made such a complaint during his interview.

An hour later, as they returned together side by side, Gidō said to him, “The Master often interrupts the recitations with cutting remarks about the novices’ indiscretions during their interviews.”

Sōsuke said nothing in reply.

21

THERE amid the temple grounds the days came and went, one after another. During that time two longish letters arrived from Oyone. Naturally neither of them contained anything untoward or unsettling. Deeply as he cared for his wife, Sōsuke procrastinated over answering her letters. Were he to decide to leave the temple without having resolved the riddle that had been posed to him, his journey would have been for naught, and he would be unable to look Gidō in the face. Every waking moment the indescribable burden of these worries weighed on him relentlessly. The more times he saw the sun rise and set over the temple compound, the more anxious he became, like a quarry closely pursued from behind. Yet he could think of no solution to the riddle other than the one he had first proposed. And no matter how thoroughly he considered other possibilities, he remained convinced that this was the only one. Still, he had arrived at this conclusion through simple ratiocination, and it hardly seemed fitting. When he tried to erase this one sure solution from the picture in order to see what compelling alternative might present itself, however, nothing whatsoever came to mind.

He pondered alone in his room. When he grew tired, he went out through the kitchen to the vegetable garden. Then he entered the grotto that had been carved out of the base of the cliff and stood there absolutely motionless. Gidō had told him that he mustn’t allow himself to be distracted. Rather, what he must do was to focus his attention ever more closely until his concentration was rigidly fixed and he himself became like a rod of iron. The more Sōsuke listened to exhortations like this, the more impossible it seemed to him that he would ever reach such a state.

“Your problem,” Gidō said another time, “is that your head is already full of the notion of getting it over and done with, and that won’t work.” His words paralyzed Sōsuke even further. Suddenly he began to think again about the return of Yasui. If he were to become a constant visitor at the Sakais’ and not go back to Manchuria for some time, the most prudent course for the couple would be to vacate their rented house immediately and move somewhere else. He could not help asking himself if, instead of idling his time away here, it wouldn’t make more sense for him to return to Tokyo right away and prepare to relocate if necessary. If it were to happen that, while he was steeling himself here at the temple, news of Yasui’s return reached Oyone, this would, he realized, greatly aggravate matters.

With the air of a man at the end of his tether, he sought out Gidō and said, “It doesn’t seem remotely possible that enlightenment will come to someone like me.” This declaration was made two or three days before Sōsuke in fact went home.

“No, that’s not true,” the monk replied without a moment’s hesitation. “Anyone with true conviction can be enlightened. You should try approaching it with the same rigid fixation as those drum-beating Nichirenites. When you have been totally permeated by the koan, from the crown of your skull to the tips of your toes, a new cosmos will manifest itself in a flash before your eyes.”

With a deep sadness Sōsuke acknowledged to himself that neither his circumstances in life nor his temperament would permit him to act with such blind ferocity— never in his entire life, let alone in the few days that remained to him at the temple. It had been his firm intention to excise from his life the net of complications that had enmeshed him of late, but this wandering off to a mountain temple had turned out to be nothing but a fool’s errand.

This was the conclusion he came to privately, but it was not in him to reveal this to Gidō. His heart was too full of admiration for this young Zen monk: for his courage and passion, his dedication and kindness.

“There’s a saying: “The Way is near yet we must seek it from afar,’ and it’s true,” said Gidō ruefully. “It’s right in front of our nose and yet we just can’t see it.”

Sōsuke withdrew to his room and set up more sticks of incense.

Regrettably this state of things prevailed until it was time for him to leave the temple. No new life opened up for him. On the day of his departure, Sōsuke, freely and without reserve, gave up any lingering hope of realizing his goal.

“You have been a great help to me through all of this,” he said to Gidō as he bade him farewell. “It’s really too bad, but things could not have turned out any other way. I doubt I’ll have a chance to see you anytime soon. I wish you all the best, then.”

“I’ve been hardly any help at all!” Gidō said, his tone most consoling. “Everything just rough and ready, you know. You must have been very uncomfortable. I assure you, though, even the amount of meditating you’ve managed to do this time makes a difference. And your having resolved to come here was a worthy accomplishment in itself.”

Nevertheless, Sōsuke keenly felt that he had merely wasted a lot of time. The monk’s efforts to put the best construction possible on it only served as a further reminder of his own weakness and, though saying nothing, he felt deeply ashamed.

“The time it takes to reach enlightenment depends on the individual’s temperament,” said Gidō. “Whether you get there quickly or get there slowly has no bearing on the quality of the experience. There are those who break through with no trouble at all only to be blocked after that from developing further; and there are others who take a long time getting through the initial steps but, once they do, experience lasting joy. You absolutely must not give up hope. The main thing is to stay passionately committed. Look at someone like the late Abbot Kōsen. He was a Confucian scholar and already middle-aged when he began to practice Zen. After he’d spent three whole years as a monk without getting past the first precept, he said, ‘It is because my sins are heavy that I have not been enlightened,’ and went so far as to bow down humbly to the outhouse every day. But see what a wise man he turned out to be. This is one of various encouraging examples I could mention.”

It was apparent that the telling of such anecdotes was Gidō’s way of trying to fortify Sōsuke against renouncing all further pursuit of this path as soon as he was back in Tokyo. He heard the monk out respectfully, but inwardly felt that this great opportunity had already more or less slipped away from him. He had come here expecting the gate to be opened for him. But when he knocked, the gatekeeper, wherever he stood behind the high portals, had not so much as showed his face. Only a disembodied voice could be heard: “It does no good to knock. Open the gate for yourself and enter.”

But how, he wondered, could he unbar the gate from the outside? Mentally he devised a scheme involving various measures and steps. But when it came to it he found himself unable to summon the strength to put his scheme into effect. He was standing in the very same place he had stood before even beginning to ponder the problem. As before, he found himself stranded, without resources or recourse, in front of the closed portals. He had been living from day to day in accordance with his own capacity for reason. Now to his chagrin he could see that this capacity had become a curse. At one extreme, he had come to envy the obstinate single-mindedness of simpletons for whom the possibility of discriminating among several options did not arise. At the other end of the spectrum, he viewed with awe the advanced spiritual self-discipline of those lay believers, both men and women, who abandoned conventional wisdom and did away with the distractions of analytical thought. It appeared to Sōsuke that from the moment of his birth it was his fate to remain standing indefinitely outside the gate. This was an indisputable fact. Yet if it were true that, no matter what, he was never meant to pass through this gate, there was something quite absurd about his having approached it in the first place. He looked back. He saw that he lacked the courage to retrace his steps. He looked ahead. The way was forever blocked by firmly closed portals. He was someone destined neither to pass through the gate nor to be satisfied with never having passed through it. He was one of those unfortunate souls fated to stand in the gate’s shadow, frozen in his tracks, until the day was done.

Just before his departure, Sōsuke, accompanied by Gidō, paid a brief visit to the Master to take his leave. The Master took them out onto the railed veranda of a room overlooking the lotus pond. Gidō went to the connecting room and returned with tea.

“It will still be cold in Tokyo,” the Master said. “When people leave after they’ve started to get the hang of it, they find that things go easier for them back home. But . . . well, it’s too bad.”

After politely thanking the Master for these parting words, Sōsuke exited the temple’s main gate, the one by which he had entered ten days earlier. The dense growth of cryptomeria, still locked in winter’s embrace, bore down on its tiles and towered darkly behind him.

![]()

Dr. Erdős György:

Nacume Szószeki

Inter Japán Magazin, 1992. május 1.

Író, költő és nem utolsó sorban tollforgató nemzedékek tanítómestere – éppen a nagy történelmi fordulat, a Meidzsi előestéjén született, 1867-ben, Tokióban. A Meidzsi kor Japán gyökeres átalakulásának válságos időszaka, a világtól elzárt szigetek ekkor léptek a nagyvilág színpadára. Érthető tehát, hogy Szószeki írásai e kor emberének képét vetítik elénk. Különösen jól érzékelhető a magyar olvasó számára annak a gondolkodó rétegnek az ábrázolása, mely a hagyományok világában már nem, az európai világnézetben még nem érzi magát otthonosan. Egyformán feszeng az ősi és az új viseletben, – akárcsak nálunk a kiegyezés után a régiből kivetkőzött magyar sem szokta meg egyhamar az új módit.

Hatodik gyermekként született egy tokiói körzeti elöljáró családjában, megélhetésük éppen a reformok miatt vált annyira szűkössé, hogy Szószeki (gyermekkori nevén Kinnoszke), vagy tíz évig nem a szülői háznál nevelkedett. A családi gondok ellenére tehetsége révén tovább tanulhatott, diákkorát egyaránt jellemzi a kínai-japán klasszicitás és a modern angol nyelv és irodalom iránti lelkesedés. Ennek köszönhetően kitűnően verselt kínaiul és japánul, olyannyira, hogy híres költői társaságok tagja lett, míg írói, oktatói pályája mégis inkább az angol kultúra vonzásának engedett.

Egyetemi évei után vidéken tanárkodott kevés előrehaladással, de nagy odaadással. Nevét a klasszikus kínai tanulmányok iránti tiszteletből Szószekire változtatta.(A kínai régiségben élt Sun Chu, akiről feljegyezték, hogy midőn remeteéletre szánta el magát, így szólt.

– A víz sodra lesz a párnám, a kövekkel pedig számat öblögetem!

– Mester! Talán megfordítva! – próbáltak javítani mondásán, mert nyelvbotlásnak vélték.

– Nem a’! – erősködött Sun – Igenis a kövekkel élesítem majd a fogam, a vizek folyása meg éppen jó lesz a fülemet tisztogatni!

Kővel szájat öblíteni – a Szószeki név jelentése – arra utal, hogy viselője nem egykönnyen hagyja magát szándékától eltéríteni.)Nacume Szószeki mindig is szembeszegült sorsával, rövid élete nem szűkölködik fordulatokban. Váratlanul hagyta el Tokiót, egycsapásra szűnik meg a félig-meddig önkéntes vidéki száműzetés is, hirtelen nősül, apósa nem kisebb ember, mint a Felsőház titkára. Szószeki mégsem politikai pályára lép, hanem Angliába utazik a század fordulóján. Az ott töltött két év csalódásokkal, súlyos gyomor- és idegpanaszokkal terhelt. Éppenséggel anyagi gondoktól sem mentes. Hazatérve két helyütt is tanít, a tokiói Császári Egyetem professzora, s egy kitűnő angol irodalomtörténet is kikerül a keze alól. Irodalmárok nemzedékeit indítja el a pályán, köztük olyanokat, mint Akutagawa, vagy Terada Torahiko. Tudósként hírnevet szerzett, az egyetem angol tanszékén Lafcadio Heart utóda, de szépírói indulása egyre késik. Megjelenik ugyan – kedvelt kínai-japán napló stílusban skóciai utazásának története, de nem kelt különösebb feltűnést. Betegségei tovább emésztik a hátralévő szűk tíz esztendőt, amit pedig később Szószeki kornak neveznek el róla az irodalomtörténészek. Egyszer azonban kísérletet tesz egy novellával, s ez azután beüt. A “Macska vagyok” című regény szépíróvá avatja a tanárembert. Egy macska szemével nézni a japánokat – ez a regény alapötlete. Talán a siker teszi, de hamar felhagy a tanári pályával, az Asahi újság irodalmi szerkesztőjeként ezután csak az írásnak él. A “macska” írásakor már harminchetedik évében jár, lázasan írja évente olykor három-négy regényét. Különösen híresek a “Fiatalúr”, a “Kapu”, a “Szív” “És azután”… Utolsó műve, a “Fény és árny” torzóban maradt, már nem tudta befejezni. Szószeki szakadatlan gyötrelmek között írta életművét, de az nem csonka, vagy zsugorított. Írónak és irodalmi jelenségnek is egyaránt nagy volt. 1916-ban halt meg.

Nacume Szószeki

Tíz éjszaka tíz álma

Eredeti cím: 夢十夜 Yumejūya

Fordította: Hani Kjóko (羽仁協子 1929-2015); lektorálta: Hrabovszky Dóra

Forrás: Hidasi Judit - Vihar Judit (szerk.): Egy magyar lelkű japán: Hani Kjóko, Budapest, Balassi, 2018. 13-30. old.

1

Egy éjszaka azt álmodtam, hogy karba tett kézzel ülök az asszony fejénél. Az asszony hanyatt feküdt, és így szólt:

- Érzem, meghalok.

Dús, hosszú haja szétterült a párnán, ovális arca hajkeretben pihent. Még átizzott fehér arcbőrén a vér pirossága, szája piros volt. Hangja határozott. Én nem hittem, hogy halálán van. Az asszony azonban csendes hangján oly határozottan jelentette ki, hogy magam is elhittem, most valóban meg fog halni.

- Igazán azt hiszed? - hajoltam az asszony fölé.

- Ez biztos - válaszolta, és fölnyitotta a szemét.

Nagy, meleg szeme volt, s ahogy a hosszú pillákon át kivehettem, koromfekete. Szeme bogarában saját tükörképem fedeztem föl.

Merőn a szemébe bámultam. Fényes, fekete, átlátszóan tiszta gömbök. .. lehet hát, hogy mégis meghal? A párnájához hajoltam, és úgy kérdeztem:

- Már meggyógyultál; ugye, nem halsz meg?

Fönnakadt szemében fáradtság tükröződött. Almatagon válaszolt:

- Meghalok. Ez nem tőlem függ.

- Látod még az arcom? - kérdeztem komoran.

- Hogy látom-e még az arcod? Milyen furcsa kérdés! Hiszen itt tükröződik a szememben! - mondta, és elmosolyodott.

Nem szóltam, visszaültem a helyemre, és karba tettem a kezem. „Hát mégis meghal" - gondoltam.

- Halálom után temessen el - szólalt meg kis idő múltán. - Gyöngy- kagylóhéjjal ássa meg a sírt, sírkőként hullócsillagot állítson fölém. És várjon ott, visszajövök, hogy láthassam még.

- Mikorra tér vissza?

- A nap föl megy, és lebukik. Megint fölmegy, és megint alábukik. A vörös korong keletről száll nyugatra, mindig keletről nyugatra. Megvár?

Némán bólintottam. Az asszony ekkor kissé megemelte hangját.

- Ha száz esztendeig vár a sírom mellett - mondta éles hangon -, biztosan visszatérek.

- Csupán annyit feleltem, hogy várok rá.

Ebben a pillanatban tükörképem elhomályosult a szembogarán. Vonásaim úgy mosódtak el, mint mikor csöndes tó fölé hajolva nézem magam, s a víz hirtelen háborogni kezd. Lezárta szemét; néhány könnycsepp, és az asszony már halott volt. Hosszú szempillája alól könnycsepp gördült végig az arcán.

Kimentem a kertbe, és gyöngykagylót kerestem, hogy megássam a sírt. A kagyló éle vidáman hasított a földbe. Ahányszor a földbe vágtam, mindannyiszor megcsillant gyöngyházán a hold fénye. A föld párolgóit, párája megcsapta az arcom.

Megástam a gödröt, aztán beléeresztettem az asszonyt. Elmerülten szórtam rá a földet a kagylóval. Ahányszor megemeltem, annyiszor csillant meg gyöngyházán a hold fénye.

A hullócsillagot is megtaláltam, s a sírdombra helyeztem. A csillag kerek volt. Arra gondoltam, hogy az űrben vált kerekké; míg földet ért, az idők folyamán koptak le sarkai. De még most is meleg volt, s míg helyére tettem, a sírra, mintha engem is melegített volna...

Karba tett kézzel leültem a mohára. Néztem a kerek sírkövet, és azon töprengtem, mi lesz velem teljes száz éven át.

Nemsokára fölbukkant a nap keletről, ahogy az asszony is mondta. Hatalmas, vörös korong. Alábukott nyugatra, ahogy az asszony is mondta. Piros köntösben sietett lefelé.

- Eltelt egy nap - szóltam.

Keletről ismét fölbukkant a piros korong és alámerült.

- Eltelt két nap - szóltam.

És így számoltam tovább. Nem tudom már, hogy hányszor pillantottam meg a vörös korongot. Számtalan vörös korong szállt át a fejem fölött kelettől nyugatig.

De száz év mégsem telhetett el. Egyre néztem a mohos hullócsillagot, miközben azt mondogattam, hogy az asszony talán becsapott.

Egyszer csak egy kék virágbimbó hajtott ki a sírkő alól, és felém hajolt. Amikor már egészen közel volt hozzám, mintha megállt volna a növekedésben. Kocsánya utolsót lengett a szélben, aztán a hosszú, karcsú szár végén kipattant a bimbó. Orromon át csontjaimig hatolt a hófehér kis liliom illata. Ekkor a magasból egy vízcsepp hullott alá, pontosan a virágra, és a szirmok megborzongtak. En a virág fölé hajoltam, és megcsókoltam a harmatos kelyhet. Amikor fölpillantottam a magas égre, láttam az esthajnalcsillagot. Egymagában tündökölt.

S csak ekkor jöttem rá, hogy már letelt a száz esztendő.

2

Második nevezetes álmom egy szerzetes szobájába vitt. Úgy kezdődött, hogy éppen elhagytam a celláját, és a folyosóról a szobámba léptem. Bent egy pislogó mécsest pillantottam meg. Letérdeltem, igazítottam a kanócon, a bél pörkölt maradéka mint áléit virág, a pirosra lakkozott állványra hullt... Hirtelen hatalmas világosság ragyogta be a szobát.

A falfülkében Mandzsusrí bódhiszattva tekercsképe lógott, szomorúfüzei rajzolódtak ki hol feketébben, hol alig észrevehetően. A képen egy halász ballagott fázósan a töltésen. Szemben a képpel, a falon egy Buszon-tekercs. Egy távolabbi sarokban tömjén illatozott.

Csönd ülte meg a szobát; a mennyezetről alácsüngő lampion árnyéka mintha életre kelt volna.

Fél térdre ereszkedve, bal kezemmel föltéptem ülőpárnám sarkát, és jobb kezemmel kitapogattam, amit kerestem. Megtaláltam. Visszahajtottam a párnát, és ráültem. Ekkor megszólalt a szerzetes:

- Te szamuráj vagy. Márpedig ha az vagy, akkor Buddha személyesen megnyilatkozik neked. Mivel mindeddig még nem nyilatkozott meg, így szamuráj voltod erősen kétséges, s az emberek között leghátul a helyed. Ha lázadni mersz szavaim ellen, bizonyítsd be, hogy Buddha megvilágosította elmédet - fejezte be a szerzetes, és elfordult.

Tudtam, hogy mire a szomszédos terem órája a következő órát üti el, addigra Buddha megnyilatkozik. S ha ez mint bizonyíték meglesz, utánamegyek a szerzetesnek, egészen a szobájába, s megszerzett bizonyítékom díjaképpen a fejét követelem. De ha mégsem tudnám bizonyítani szamuráj voltomat, nem kérhetem az életét, hiszen én szamuráj vagyok. Ha nem sikerül magam tisztára mosnom, önkezemmel vetek véget életemnek, mert egy szamuráj nem élhet becstelenségben.

Idáig jutva gondolataimban, önkéntelenül visszanyúltam az ülőpárna alá. Előhúztam a tőr piros tokját, aztán markolatánál fogva kirántottam a pengét. Éle villogott a sötét templomban, s éreztem, iszonyú erők szabadulnak föl kezem nyomán, hogy a tőr hegyén összpontosuljanak. Láttam, hogyan vékonyodik, élesedik, válik tűhegyessé a penge vége; egészen addig néztem, míg meg nem született bennem a vágy: szúrni, ölni vele! Vérem is jobb kezembe szállt, s ettől a markolata csúszkált a kezemben. Szájam reszketni kezdett.

Visszacsúsztattam tokjába a tőrt, és magam mellé tettem. Aztán úgy helyezkedtem, ahogy írva van: belebámultam a semmibe, vártam a kinyilatkoztatást. De az egyre késett. Dühbe gurultam, és gondolatban fenébe küldtem a szerzetest. Fogaim összecsikordultak, és orromból a düh forró levegője sípolt elő. Halántékom mintha kalapálták volna, szemem iszonyatosra tágult. Egyszerre láttam a falitekercset, a lampiont és a pap kopasz fejét; hallottam, hogy nevet krokodilszájával. Átkozódtam, és a pokolba kívántam, szerettem volna lenyakazni, pedig hittem, hogy megvilágítja elmém Buddha. A Semmit akartam, a Semmit, miközben mélyen magamba szívtam a tömjénfüstöt. Ökölbe szorított kezemmel dühödten csaptam a saját fejemre. Fogaim ismét összekocódtak, kivert az izzadság. Gerincem nem hajlott, mintha karót nyeltem volna! Térdem fájdalomtól sajgott, már azt sem bántam volna, ha lábam eltörik. Kínlódtam, de a Semmi csak nem mutatkozott. Mert bármit tettem is, mindig gondolnom kellett valamire, bármire, s így egyre messzebb került tőlem a Semmi állapota. Ha más nem, az jutott eszembe, hogy kínlódom. Haragudtam magamra, sírni kezdtem. Legszívesebben leugrottam volna egy kiálló, magas szikláról, hogy pozdorjává zúzódjam.

De nem, mozdulatlan maradtam. Várakoztam, szívemet végtelen kétségbeesés szorongatta. A kétségbeesés szinte fölemelt, pórusaim tágítgatta, és nem talált kiutat belőlem.

Arra lettem figyelmes, hogy a fejemmel valami nincs rendben. Úgy tűnt, mintha egyszerre létezne is, meg nem is a lampion, a Buszon-te- kercs, a tatami és a polc. De ez mégsem volt maga a Semmi. Tagjaim elzsibbadtak ültömben. A szomszédos teremben ütött az óra, mire fölriadtam.

Kezem a tőrre tévedt. Az óra akkor ütötte el a kettőt.

3

Harmadik nevezetes álmomban hátamon egy hatesztendős forma gyereket cipeltem. A saját gyerekemet. Furcsálltam hát, hogy ez a gyerek vak és kopasz. Meg is kérdeztem:

- Te mikor vakultál meg?

- Már régen - felelt. Gyerek hangja volt a hang, de mégis, mintha felnőtt szólt volna, sőt akár barátom is lehetett volna. A sötétben is láttam a környező rizsföldek zöldellő vonalait. A keskeny útra kócsagok árnya vetődött.

- Rizsföldön járunk - szólalt meg fiam a hátam mögött.

- Honnan tudod?

- Hallom a kócsagokat - mondta.

Ekkor valóban kétszer kelepelt egy kócsag.

Féltem a fiamtól. Hát kit hordok én a hátamon? Azon gondolkodtam, hogyan szabadulhatnék tőle. Aztán egy erdő körvonalai rajzolódtak ki a sötétben. Megvan! De ebben a pillanatban nevetés hallatszott.

- Mit nevetsz? - kérdeztem.

- Apa, én nehéz vagyok neked ... - mondta felelet helyett.

- Ugyan!

- Pedig meglátod, nemsokára nehéz leszek!

Nem szóltam, némán lépdeltem az erdő felé. Az út egyre fárasztóbbá vált, a keskeny dűlő kanyargós lett. Nemsokára egy útkereszteződéshez értünk. Fáradt voltam, leültem.

- Valahol itt lehet a mérföldkő - mondta a fiam.

Körülnéztem, és fölfedeztem a derékmagas követ. Rajta a felirat:

BALRA HORIDAHARA, JOBBRA HIGAKUBO. Éjszaka volt, a vörös betűk mégis jól látszottak, valósággal világított a színük, akár a piros hasú gyíké.

- Menj balra - figyelmeztetett a fiú.

Balra néztem: a távoli égbolton át egészen a fejünk fölé kúsztak az erdő sötét árnyai... Pedig oda szerettem volna eljutni, de mégis tétováztam.

- Ne félj - biztatott -, légy nyugodt.

Elindultam az erdő felé. Magamban mormogtam, csodálkoztam: hogy tudhat mindent, amikor nem is lát? Nemsokára megszólalt:

- Nem valami jó dolog vaknak lenni!

- Nem jó? Tudom, ezért viszlek a hátamon.

- Köszönöm, hogy viszel. A vakot nem szeretik az emberek. Még a saját apja sem szereti.

Már nem tetszett nekem a menetelés. Szaporábban léptem, hogy mielőbb az erdőben hagyhassam a fiút.

- Bírd még egy kicsit... Menj még egy kicsit, s meglátod... Épp egy ilyen estén történt.- duruzsolta félhangon a fiú.

- Micsoda? - kérdeztem gyanakvóan.

A fiam megvetően válaszolt:

- Hisz tudod te jól, micsoda! - válaszolt a fiú megvetéssel.

Már én is tudtam, miről van szó. Nem határozottan, de tudtam. Igen, akkor is éjszaka volt... De mindent megtudok, ha beérünk az erdőbe. Ereztem, gyorsan ott kell hagynom, hogy megnyugodjak.