ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

晦堂祖心 Huitang Zuxin (1025-1100), aka 黃龍 Huanglong

(Rōmaji:) Kaidō Soshin, aka Ōryū

Tartalom |

Contents |

| Gabalyodó indák Fordította: Terebess Gábor |

HUITANG ZUXIN, “HUANGLONG” Entangling Vines: Zen Koans of the Shūmon Kattōshū |

HUITANG ZUXIN, “HUANGLONG”

by Andy Ferguson

In: Zen's Chinese Heritage: The Masters and Their Teachings, Wisdom Publications, pp. 424-428.

HUITANG ZUXIN (1025–1100) was a disciple of Huanglong Huinan. He came from Guangdong Province. He left home at the age of nineteen to live at Mt. Long’s Huiquan Temple. His first Zen teacher was named Yunfeng Wenyue.200 After studying for three years, the young monk had achieved no breakthrough, so he advised Yunfeng of his desire to leave. Yue said, “You must go see Zen master Huinan at Huangbo.” Huanglong then went to study under that teacher, but after four years he still hadn’t gained clarity. He then departed and returned to Yunfeng.

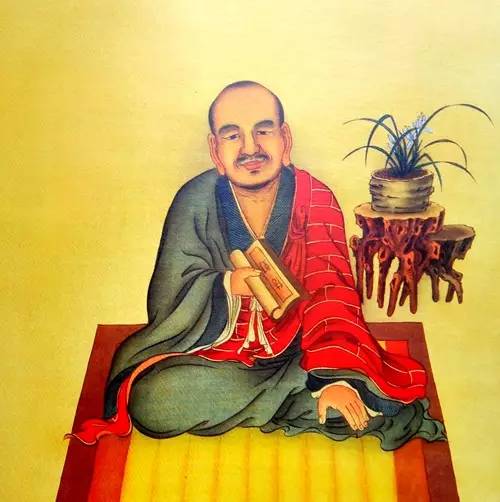

Illustration by 李蕭錕 Li Xiaokun (1949-)Huitang discovered that Wenyue had passed away, and so he stayed at Shishuang. One day he was reading a lamp record when he came upon the passage, “A monk asked Zen master Duofu, ‘What is Duofu’s bamboo grove?’ Duofu replied, ‘One stalk, two stalks slanted.’ The monk said, ‘I don’t understand.’ Duofu then said, ‘Three stalks, four stalks crooked.’” Upon reading these words Huitang experienced great awakening and finally grasped the teaching of his previous two teachers.

Huitang returned to see Huanglong Huinan. When he arrived there and prepared to set out his sitting cushion, Huinan said, “You’ve already entered my room.”

Huitang jumped up and said, “The great matter being thus, why does the master teach kōans to the disciples and study the hundred cases [of the kōan collections]?”

Huinan said, “If I did not teach you to study in this manner, and you were left to reach the place of no-mind by your own efforts and your own confirmation, then I would be sinking you.”

A monk asked, “What was it before you ascended the Dharma seat?”

Huitang said, “There weren’t any affairs.”

The monk asked, “How about after you ascended the seat?”

Huitang said, “Lifting my face toward the sky, I don’t see the sky.”

Huitang said, “Those who want to understand the source of life and death must first clearly understand their own selves. Once they’re clear about this, then afterward they can act appropriately according to circumstances, never missing the mark.

“Before the sword appears, there is no ‘positive’ or ‘negative.’ But when it comes forth, then there are the five elements, mutually giving rise to or overcoming one another. The alien and familiar are manifested, and the four natures come into abiding. Everything becomes pigeonholed, and the sword of ‘yes’ and ‘no’ arises.

“But this leads to that which is true and false not being distinguished, to water and milk not being separated. When a disease enters into the solar plexus of a person, how can he be saved? If a weary and lost traveler doesn’t have the bright sun to assist him, he won’t find his way back home. When a person truly beholds the great function, then all delusional views are immediately forgotten. When all views are forgotten, the mist and fog are not created. When great wisdom is understood, then there is nothing else. Take care!”

Huitang entered the hall and addressed the monks, saying, “‘It’s not the wind that moves. It’s not the flag that moves.’ A clear-eyed fellow can’t be fooled. But you worthies’ minds are moving slowly. Where will you look to see the ancestral teachers?”

Huitang then threw down the whisk and said, “Look!”

Huitang addressed the monks, saying, “If someone understands the self without understanding what is before the eyes, then this person has eyes but no feet. If he only awakens to what is before his eyes without understanding the self, then this person has feet, but no eyes. Throughout all hours of the day these two sorts of people possess something that is located in their chests. When this thing is in their chests, then an unsettled vision is always before their eyes. With this vision before their eyes, everything they meet gives them some hindrance. So how can they ever find peace?

“Didn’t the ancestors say, ‘If anything is grasped or lost, one enters the heretical path. When things are left as they are, the body neither goes nor stays’?”

Huitang entered the hall. Striking the meditation platform with his staff, he said, “When a single speck of dust arises, the entire earth fits inside it. A single sound permeates every being’s ear. If it is like a lightning swift eagle, then it’s in accord with the vehicle. But in stagnant water, where the fish are lethargic, it’s hard to whip up waves!”

Huitang entered the hall and said, “Before the appearance of skilled craftsmen, jade could not be separated from stone. Without skilled metallurgists, gold can’t be removed from sand. Can someone gain enlightenment without a teacher or not? Come forward and let’s check you out.”

Huitang then raised his whisk and said, “Tell me, is it gold or is it sand?”

After a long pause, he said, “Don’t think of it as here before you. Imagine it a thousand miles away.”

Huitang entered the hall and recited a verse:

Not going,

Not leaving,

Thoughts of South Mountain and Mt. Tiantai,

The silly white cloud with no fixed place,

Blown back and forth by the wind.

Huitang, when interviewing a monk in the abbot’s quarters, would often raise a fist and say, “If you call it a fist I’ll hit you with it. If you don’t call it a fist you’re being evasive. What do you call it?”

Before he died, Huitang ordered that his funeral be conducted by his disciples and by [his student] Wang Tingjian, the local governor. During the cremation ceremony, Linfeng tried to light the pyre with a candle on behalf of the governor. The pyre would not light.

Governor Wang then spoke to Huitang’s senior disciple, Sixin, saying, “The master is waiting for our senior brother to light the fire.”

Sixin ritually refused Wang’s request, but the governor urged him to take the candle.

Finally, taking the candle, Sixin raised it before the assembly and said, “What evil have I committed that brings me to this? A great crime is hard to absolve! [Then facing the pyre, Sixin said,] Now, Master, you go on foot into emptiness. If you can’t ride an ox, please use a donkey!”

Sixin then drew a circle in the air with the candle, saying, “Here, all defilement is purified!”

He then threw the candle onto the pyre, which instantly erupted into flames.

Huitang’s remains were interred on the east side of the “Universal Enlightenment Stupa.” The master received the posthumous title “Zen Master Precious Enlightenment.”

DOC: Huanglong pai

The lineage of the Huanglong branch of the Linji school

宗門葛藤集 Shūmon kattōshū

Entangling Vines: Zen Koans of the Shūmon Kattōshū

Translated by Thomas Yūhō Kirchner

Case 18

Shangu’s Sweet-Olive BlossomsOne day the poet Shangu was visiting Huitang Zuxin. Huitang said, “You know the passage in which Confucius says, ‘My friends, do you think I’m hiding things from you? In fact, I am hiding nothing from you.’* It’s just the same with the Great Matter of Zen. Do you understand this?”

“I don’t understand,” Shangu replied.

Later, Huitang and Shangu were walking in the mountains where the air was filled with the scent of the sweet-olive blossoms. Huitang asked, “Do you smell the fragrance of the blossoms?”

Shangu said, “I do.”

Huitang said, “You see, I’m hiding nothing from you.”

At that moment Shangu was enlightened.

Two months later he visited Sixin Wuxin. Sixin greeted him and said, “I’ll die and you’ll die and we’ll end up burnt into two heaps of ashes. At that time, where will we meet?”

Shangu tried to respond but couldn’t come up with anything. Later, while on the road to Qiannan, he awoke from a nap and suddenly understood Sixin’s intent. Thereafter he attained the samadhi of perfect freedom.

*Analects 7:23.

宗門葛藤集 Shūmon kattōshū

Gabalyodó indák

Fordította: Terebess Gábor

18. San-ku illatcserjéje

Egy nap a költő San-ku1 meglátogatta Huj-tang Cu-hszin-t.2 Huj-tang azt mondta:

– Ismered Konfuciusz3 mondását: „Azt hiszitek, barátaim, van valami titkom előttetek? Semmit sem titkolok előletek.” Ugyanez a helyzet a zen legfontosabb ügyében is. Érted, miről van szó?

– Nem értem – válaszolta San-ku.

Később Huj-tang és San-ku kirándultak a hegyekben, a levegőt betöltötte az virágzó illatcserje4 bódító aromája. Huj-tang azt kérdezte:

– Érzed a virágok illatát?

– Érzem – mondta San-ku.

– Látod, nem titkolok előled semmit.

Abban a pillanatban San-ku megvilágosult.Két hónappal később meglátogatta Sze-hszin Vu-hszin-t.5 Sze-hszin üdvözlésül azt mondta:

– Én is meghalok, te is meghalsz, végül két kupac hamu lesz belőlünk. Akkortájt hol találkozunk?

San-ku próbált valami felelni, de semmi nem jutott az eszébe. Később a Csiennanba vezető út szélén, felocsudva álmából, megértette Sze-hszin szándékát. Ezután elérte a tökéletes szabadság szamádhiját.1San-ku Tao-zsen / Shangu Daoren [Rōmaji: Sankoku Dōjin] 山谷道人 (1045–1105), Huang Ting-csien / Huang Tingjian [Rōmaji: Kō Teiken] 黃庭堅 költői álneve

2Huj-tang Cu-hszin / Huitang Zuxin [Rōmaji: Kaidō Soshin] 晦堂祖心 (1025–1100)

3Konfuciusz beszélgetései és mondásai, VII:23

4illatcserje virága / muxihua [Rōmaji: mokuseika] 木犀花 (Osmanthus fragrans)

5Sze-hszin Vu-hszin/ Sixin Wuxin [Rōmaji: Shishin Goshin] 死心悟新 (1044-1115)