ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

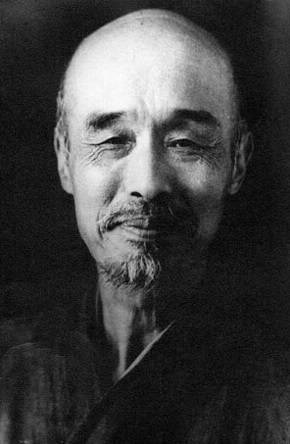

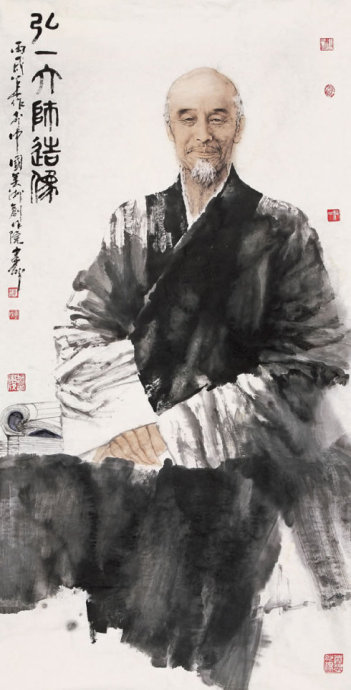

弘一 Hong Yi (1880-1942)

born 李叔同 Li Shutong

http://www.buddhistdoor.com/OldWeb/bdoor/0202/sources/hongyi.htm

The original name of Hongyi is Li Shutong. He was born in 1879 and became a monk at the age of 39. He died at the age of 63 in 1942.

Li Shutong came from a wealthy family in the northern city of Tiantsin in China. He was only 5 years old when his father passed away. He was brought up by his half brother who was 12 years his senior.

His mother passed away when he was 26 years old. He then went to Japan to study arts and music. While in Japan, he organized a drama group, which later on moved back to China. Their performance marked the beginning of modern drama in China. Upon return to China, he worked for seven years as a music and arts teacher in the First Normal University of Zhejiang Province at Hangzhou. Li was the first artist in China to compose a chorus and nearly all of the first generation music teachers in China were his students. Li was also a famous calligrapher at that time.

In 1918, when Li was 39 years old, he became a monk in the Hangzhou Hupao Temple under the Buddhist Master Liaowu and thus became Master Honhyi. Since then, he gave up all his pursuit in artistic creation other than calligraphy and painting related to buddhism.

In 1942, at the age of 63, he passed away in the Quanzhou Senior Home in Fujian Province.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hong_Yi

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Song_Bie_Ge

Li Shutong and Writing Life's Stories

Posted 15th February 2009 by Peter Micic

http://animperfectpen.blogspot.hu/2009/02/li-shutong-and-writing-lifes-stories.html

I have spent a lot of my time writing about people's lives. Most if not all of them are Chinese, and most of them are well and truly dead.

Why do we love to read biographies? Because they allow us to eavesdrop into the private dramas of a life, to share their trials and tribulations and help us to understand that their successes or failures are neither exceptional or mysterious. Along the way we learn how our hero sinks or swims in the face of adversity, how obstacles are overcome, and what it takes to ultimately triumph. We read of experiences and events that are both unique and shared.

Those who can write a story with one eye on the subject's life, another on history, and a third, on the human condition, and do it with grace and style that persuades us, for the moment at least, that nothing is more important than to have the reader right where they want them: on the page.

The writing of a life (or a slice of it) can be recounted, for example, as a short story, novel, fairytale or fable. Imagine given the main actors and a synopsis of Charlotte's Web and then asked to write a short story based on it. There will be many variations. Each storyteller has the basic raw materials, but the storytelling says a lot more about the storyteller than the story itself.

For me, the challenge of writing about anyone's life is not to forget the beauty of saying something clearly and simply. I love the story of Beth Gellert collected by the folklorist Joseph Jacobs, the Celtic tale of a loyal dog killed by its master and its cautionary warning of rash action because of its sheer brevity and simplicity. I also love a story of epic proportions when told by a consummate storyteller (Vikram Seth's A Suitable Boy comes readily to mind). In both these examples, the storyteller not the story is in charge.

Let me give you one example of my own modest efforts to write biographies. Over a decade ago, I was researching the life of a late Qing and early Republican figure called Li Shutong (1880-1942). He was what you might describe as the great all-rounder of early twentieth century China—writer, poet, painter, calligrapher, actor, songwriter, music educator—and while we're at it, let's add practising Buddhist monk where he was known by the Buddhist name The Dharma Master Hongyi.

His early life coincided with what is often referred to as the 'transitional period' dating from the 1890s and ending with the collapse of China's last imperial dynasty in 1911. This 'transitional period' saw the emergence of many professional groups of reformers who emphasized the political and social relevance of culture that could promote various goals and reform China through the creation of a modern culture.

Li Shutong was born in the port city of Tianjin. His grandfather was a wealthy salt merchant and banker originally from Jiaxing in Zhejiang Province, His father Li Xiaolou was a scholar, an avid reader of the Ming Neo-Confucian thinker Wang Yangming (1472-1529) and Chan (Zen) Buddhism. He had fathered Shutong by a concubine in his early seventies. Li's father died when he was four years old leaving him under the care of his mother, then only in her twenties, and his half elder brothers Wen Jin and Wen Xi.

Li's early years of education came under the guidance of his two half brothers who gave him a solid grounding in the Confucian classics. He also began learning painting and seal carving and also displayed an early preoccupation with religion, memorising, liturgical texts recited by Buddhist monks at family memorial services. 'When I was only five years old,' Li wrote in an essay published in 1937, 'I often met monks and many of them performed religious services at our home. By the time I was twelve or thirteen I could already recite rituals of exorcism.'

Li was preoccupied with study and contemplating the transience of human existence long before he took his vows as a Buddhist monk at the age of thirty-eight, but he was by no means a recluse or hermit. Betrothed to a woman with the surname Yu from a family of tea merchants in Tianjin at eighteen, Li fathered two sons, the eldest named Zhun born in 1900 and the youngest Duan, born four years later. He was sympathetic to Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao, two prominent reformers of the time. Kang and Liang fled to Japan following the debacle of the 1898 Hundred Days Reform. Li's support for reform, however, forced him to flee not to Japan, but to Shanghai with his mother.

Li's artistic proclivities endeared him to many of the literati in Shanghai where he set up house in the French concession. His talents came to the notice of Xu Huanyuan, the principal patron of the Southern City Literary Society. Xu invited Li and his mother to take up residence in his secluded villa where Li could devote his time to writing and painting. Li and his mother lived in a small apartment in the villa 'surrounded by ancient willows and bordered by a meandering brook.'

Li's mother died in early 1905. The loss of his mother was an important factor in his decision to go to Japan in August. If his mother had not died, Li most likely would have stayed in Shanghai pursuing his many interests. With his mother's death, Li changed his name to Li Ao—Li who mourns (for his mother). He used scores of pseudonyms throughout his life and each major turning point gave birth to a new pen name.

Li was already a celebrity before arriving in Japan. He enrolled at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts studying Western oil painting under Kuroda Seiki (1866-1924), one of the leading oil painters in Japan and studied piano and composition. In 1906 he became the editor of the Little Music Magazine . In the preface, we are drawn into a place where music can ‘beautify the souls of mortals' and ‘transform social norms', but in the final paragraph, written January 3 1906, Li produces an intense affect of being forlorn and stranded while contemplating the fate of the nation:

Our nation has lost its strength and is no longer strong or prosperous. A transverse flute's doleful sound carries tears from the southern slopes. Sentiments of opposing the Qing and restoring the Ming are found in Ruan Dacheng's Spring Lantern Riddles and The Swallow Letter . The sun has already set in the west. The tune Jade Flower in Rear Court attributed to the emperor Chen Shubao conjures up decadent music presaging the collapse of a dynasty. An anxious moon and a desolate wind accompany the uneven sounds of a reed pipe. China's uncertain future hangs in the balance. In the corner of a tavern I sit alone, the evenings pass by like years. I pick up my pen but can't write a word, reduced as I am to weeping tears.

Despite Li's penchant for painting and music, it was in drama that he attracted the most attention. He was a skilled amateur performer in Chinese opera. In 1906 he formed the Spring Willow Society with a number of overseas Chinese theatre enthusiasts in Tokyo. The following year the Society performed a number of plays including Black Slaves Cry to Heaven translated by Lin Shu and based on Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel Uncle Tom's Cabin and La Dame aux camélias . These plays took the Tokyo drama world by storm and their performances were a roaring success acclaimed by both Chinese and Japanese critics.

Li left the Spring Willow Society in the winter of 1908 to devote his time to painting and music. He graduated from the Tokyo School of Fine Arts in March 1910 and returned to Tianjin taking up a teaching position as drawing teacher at the Zhili Normal Technical Institute in Tianjin. In 1912, Li's family fortune suffered a huge blow on the stock market leaving Li and his two half brothers on the brink of bankruptcy. Li moved back to Shanghai in the spring and taught music at the East Shanghai Girls' School. He also became actively involved in a number of newly-formed literary societies in the early days of the new Republic.

In 1913 Li was invited by Jing Hengyi--the principal of the Zhejiang Two-Level Normal School--to teach drawing and music in Hangzhou. As a teacher Li was noted 'for his clear, painstaking way of teaching and for his high example of seriousness and probity.' Li's influence on two of his students Feng Zikai (1898-1975) and Liu Zhiping (1894-1978) was so profound that it was to play a crucial role in Liu Zhiping's decision to take up music, and in the case of Feng, art, as careers.

Li was admired as a teacher but his extracurricular activities included periods of fasting and meditation. In early 1918 he wrote to Liu Zhiping:

I have made the decision to become a Buddhist monk. Last winter I spent a lot of time with Ma Yifu, and finally awakened to the realisation about the transience of all things. Life has become insipid and tasteless and I no longer have the desire to pursue a professional career. Recently, I've taken an extended leave of absence, but feel guilty I can't devote more time to teaching.

Five years earlier while drinking tea at the Lake Heart Pavilion on West Lake, one of his colleagues made the passing comment to Li that it wouldn't be such a bad idea if the two men shaved their heads and became monks. Li took the tonsure in July 1918. He had given away seals, scrolls, clothes, paintings and other belongings in mid April. There were reports that his wife, children and 'Japanese concubine' called Yukiko, who he had brought back from Japan, arrived at the monastery in the hope of dissuading Li from becoming a monk but to no avail. The one time cultural media star would achieve a different kind of celebrity as a monk of the Vinaya or Disciplinary School ( Lüzong ) of Buddhism founded by Dao Xuan during the early Tang dynasty.

Why did Li become a monk? Many events in his life have been proposed. In the second volume of the Biographical Dictionary of Republican China (1968):

Although Li Shutong had lived a full and sophisticated life, at least up until his return from Japan, he later confided to friends that he had never known true happiness and that as a layman he had never been without a depressing sense of the transience of all things. The death of his father in 1884, the failure of his political dreams in 1898, the death of his mother in 1905, his loveless marriage and complicated family life, and the political confusion and the loss of his fortune in 1912 eventually led him to a thoroughgoing reexamination of his life and his place in it[1].

And Geremie Barmé:

[T]here is some evidence that his turning to religion was inspired as much by his mother's death as his frustrated patriotism (or even romanticism that had run its course). He returned to China just as the dynastic system collapsed, hopeful like so many of his generation who were still interested in traditional Confucian thinking that education—both the communication of new learning and the moral influence of one's personality—were in the new circumstances the most efficacious way to realise the aims of the revolution. Yet with the failure of the ‘Second Revolution' to overthrow Yuan Shikai and increasingly political turmoil, Li felt drawn towards new ways of transforming himself....entering the Buddhist monastic order in 1918 marked the end of the search [2].

Li's 'new life' did not signal the end of his artistic endeavours or the closing of doors of his former students, colleagues and friends. Li, however, took his vows and practice very seriously.

By early 1942, austerities and fasts began to take their toll on Li's health and by mid-May, he was deteriorating rapidly. Three days before he passed away at Busi temple in Quanzhou on October 13, Li wrote his last brushstrokes of calligraphy: 'Worldly Joys and Sorrows Are Intertwined.' ( Beixin jiaoji ). These four characters were taken from the sixth century text on worship of the Bodhisattva Dizang (Ksitigarbha) called Scripture on Divining the Retribution of Skillful and Negative Actions ( Dizang pusa zhancha shan'e yebao jing ) and used in an inscription by Li in the winter of 1932.

------

Much of the legend and hagiographic depictions of Li Shutong have essentially focused on his life after he became a Buddhist cleric in 1918. In the process of edification, Li Shutong is no longer Li Shutong, but Hongyi fashi (Dharma Master Hongyi), amply illustrated in the titles of numerous books and articles known as Hongyi fashi studies ( hongxue ).

In collecting material on Li Shutong's life I relied heavily on one meticulously research chronological biography edited by Lin Ziqing (1995) as well as maudlin and fictionalized stories and accounts found in several Chinese novels. In the chronological biography, I was presented with a crowded house of detailed notes of Li's life. Not the kind of biography to go looking for elegant, imaginative prose.

With novels and fictionalized accounts, the pendulum swung to another extreme where writers were keen to tell the reader that there is a good story to tell, whether it be strictly true or not, and proceed to embellish or alter it for purposes of fiction taken from 'real' life. For example, stories of how Li met Yukiko in Tokyo and the futile efforts of his wife, children and Yukiko to dissuade him from taking his vows as a Buddhist monk have been sensationalized in novels as well as soap operas in mainland China.

How do we distinguish between history and fiction? There are many other questions contained in that question. The Australian author Nicholas Jose says that great fiction allows to us to view 'a profound historical understanding of the world..' He also writes:

bad history in fiction of course means bad fiction. Historians rightly share a professional suspicion of fiction. Novelists, I think, are respectful of historians. Yet in our quest for new narratives we are compelled at a certain point to kick away the scaffolding and enter an imaginative domain where the facts, always open to multiple interpretations, may not answer every question [3].

An issue that particularly interests me with biography concerns the 'facts'or 'real events' of the subject's life. Armed with a litany of questions, we find that our subject may contradict, embellish or distort events of his or her life or has no interest in recognizing certain things about it. This brings us to the problem of explanation. We could say this, but we could easily say that. Where do we go from here, what focus or angle do we take?

Embellishing or adding to ‘real events' should not mean lying or complete misrepresentation, but it does require the biographer's grasp of the wider social and political setting of the subject's life and the skill, empathy and imagination to produce a plausible and intelligent narrative that does not leave the reader constantly begging the question: How can the biographer be sure of this?

There are many things that we can focus on a subject's life leading us into various directions and taking us into unexpected corners. We would expect at the end of our labour intensive efforts, tirelessly sitting for hours in libraries or archives and patiently conducting interviews with the subject or witnesses (if that be the case), that we are rightly adding new dimensions of understanding to the life of an artist, writer or composer. However, what gets lost or buried underneath the minutiae of a life, especially when we are trying to understand the work of the artist, writer or composer is the very thing that remains elusive and impressionistic: the mysteries and nature of 'artistic creativity.' In this context, stories and the private dramas of a life are perhaps:

all false tracks, red herrings, dead-ends; they lead nowhere. What a zealous researcher might catch in his net—after dragging bleak expanses of mud—would hardly repay his efforts. Every life leaves behind an accumulation of broken odds and ends—bizarre and sometimes smelly. Rummaging there, one can always unearth enough evidence to establish that the deceased was both monstrous and mediocre. Such a combination is quite common—whoever doubts it only needs to look at himself in a mirror [4].

There is something undeliably voyeuristic about writing about the life of another, finding letters in an archive not for public reading or digging up someone else's secrets. The experience is not always pleasurable. Looking at old photographs in a book prompted me to ask who was Li Shutong whose life I'm now looking into? How did he construct his world, what was his vision of it? I could snoop around archives, looking, probing for evidence, but it was much harder to explain his compositional choices in writing school songs from the vast repertoire of Chinese and foreign tunes.

In my thumbnail sketch of Li Shutong's life, I decided to devote a little more space to why he became a Buddhist monk because it was a major turning point in his life. There were other anchor points of course, but I decided to write a little more for the simple reason that this episode in his life was no trivial matter and I was intrigued to find out more about the circumstances that led his decision to take the tonsure.

Notes

[1]. Boorman, L Howard (ed.), Biographical Dictionary of Republican China 1967 vol. II, New York: Columbia University Press, 1968:324.

[2]. Barmé, Geremie Feng Zikai: A Biographical Sketch and Critical Study, 1890-1975 , PhD, Australian National University, 1989:175.

[3]. Jose, Nicholas 'Any Resemblance is Unintended' http://www.nla.gov.au/events/history/papers/Nicholas_Jose.html

[4]. Leys, Simon, ‘The Truth of Simenon' in The Angel and the Octopus , Sydney: Duffy & Snellgrove, 1999:131.

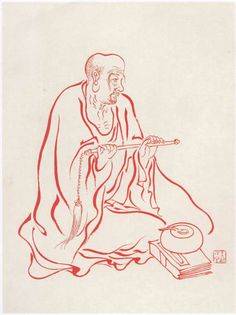

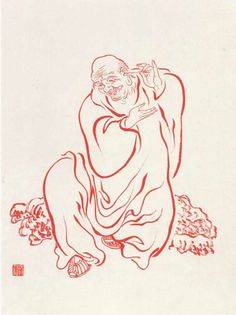

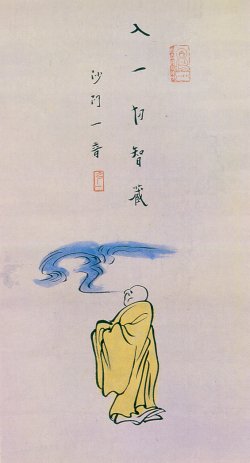

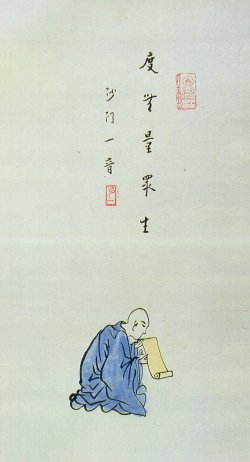

弘一法师108罗汉图 Arhats

https://www.sohu.com/a/125693270_497733

Wisdom

Beings

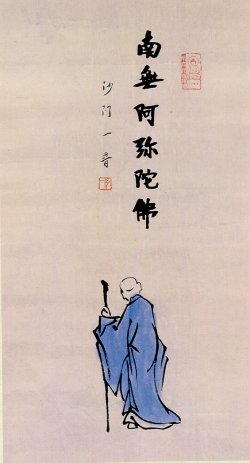

Amitabha

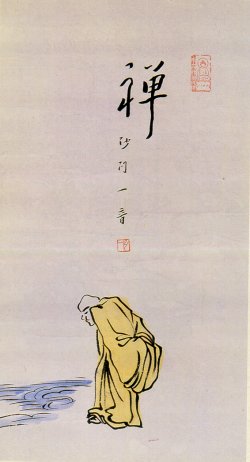

Zen

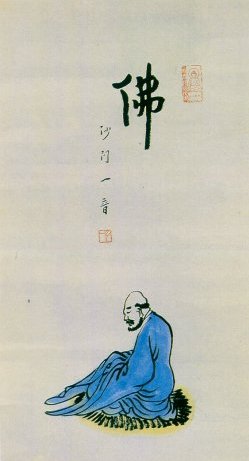

Buddha