ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

風外慧薰 Fūgai Ekun (1568-1654)

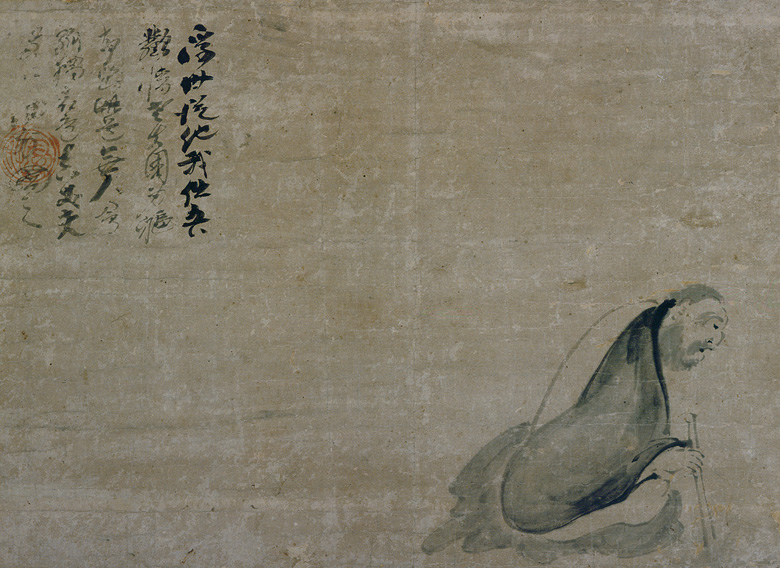

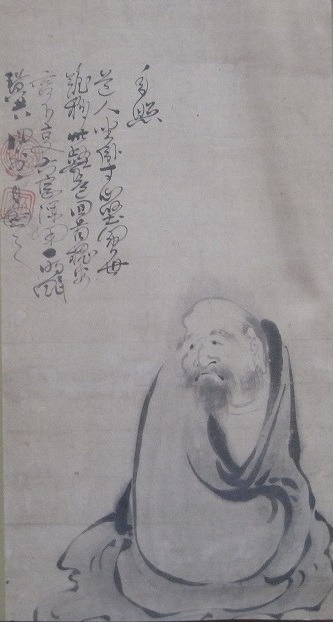

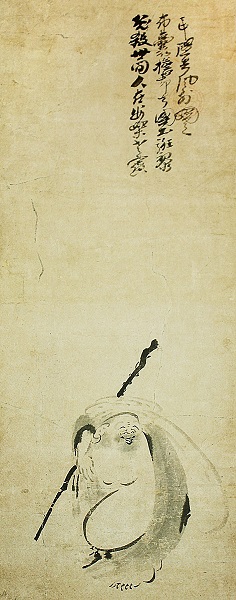

「穴風外」 Ana Fūgai ('Cave Fūgai') 「風外自画像」

「風外自画像」 Self-portrait

http://www.kihindo.jp/kobokuseki/soutou/ekun.html

http://zenpaintings.com/artist-Fūgai.htm

Japanese Zen monk, painter and calligrapher. He entered the Shingon-sect temple Kansoji at the age of four or five, transferring to the Soto-sect Zen temple Chogenji a few years later. Around the age of 16 he moved to the leading Soto temple in eastern Japan, Sorinji. After completing his Zen training, perhaps in 1596, Fūgai spent two decades on pilgrimage. In 1616 he became abbot of Joganji in Sagami Province (now part of Kanagawa Prefect.), but after only a few years he gave up his position to live in mountainside caves, which earned him the nickname 「穴風外」 Ana Fūgai ('Cave Fūgai'). This practice may have been in emulation of Bodhidharma (Jap. Daruma, the first Zen patriarch), who was reputed to have meditated in front of a wall for nine years; but such rejection of temple life was rare for a 17th-century Japanese monk. While living in the Kamisoga Mountains, Fūgai is said to have made ink paintings of Daruma, which he would hang at the entrance to his cave, so that farmers could leave rice for the monk and take the paintings home. Many such works remain, darkened by incense, in farmhouses of the region. After some years Fūgai moved to a small hut in the village of Manazuru, south of Odawara, where he continued his ink painting and calligraphy. Besides Daruma, he also depicted the wandering monk Hotei (Chin. Budai; one of the Seven Gods of Good Fortune) and occasionally brushed self-portraits and landscapes in ink on paper.

Fūgai Ekun (1568-1654): "OUTSIDE THE WIND"

In:

The art of Zen : paintings and calligraphy by Japanese monks, 1600-1925

by Stephen Addiss

New York : H.N. Abrams, 1989. pp. 44-58.

The paintings of Fūgai Ekun, simply brushed with ink on paper, convey a

depth of spirit that makes them unique even within the sphere of Zen art. His

works are imbued with a haunting intensity; the eyes of the figures he depicts

penetrate deep into the human spirit, providing a sense of direct communication

with the artist. Yet Fūgai has not received the recognition that other Zen

artists have been given, in large part because he lived far away from the major

cultural centers, had no pupils, and founded no school.

Historically, Fūgai was the first important Zen monk-painter of the Sōtō

sect, and in the eyes of a few connoisseurs he remains the greatest master of ink

painting in the Sōtō lineage. Artistically, he represents a transition from

earlier brushwork traditions to those of the Edo period, and his work presages

many of the important features of later Zenga. Fūga'is style of painting was

rooted in the past, especially his use of gray-wet brushstrokes with small

accentuations in black. This style of figural depiction, known as "apparition"

or "ghost" painting, was favored by Chinese Zen artists of the Sung dynasty

as well as by early Japanese monk-painters.

Fūgai's choice of subject matter was also traditional. The Zen patriarch

Daruma and the wandering monk Hotei were his favorite subjects, although

he occasionally attempted portrayals of other Zen masters as well as birds and

plants and landscapes. Fūgai's emphasis upon Zen figures, painted simply

and without background detail, was part of a significant trend in Edo-period

monk painting; exemplars of enlightenment were chosen because they were

good models for those who wished to follow a Zen life. Fūgai also anticipated

future directions in Zenga by inscribing his own poems on his paintings-- a

practice that was rare before his century--and by brushing informal selfportraits

quite different from the elaborate chinsō (colorful and detailed depictions

of monks) that had long served as Zen portraiture.

Fūgai's life was as individualistic as his artworks. He did not follow tradition

by residing in temples, nor did he rise to a position of prominence in the

Zen hierarchy. Instead he spent many years wandering, living at times in

caves and eventually settling in a hut in a mountain village. His final years

were spent in nomadic travel; he died almost literally "on the road." Details

about Fūgai's life are incomplete and sketchy, in part because he has long been

confused with two other Sōtō Zen monks who used the same name, which

literally means "Outside the Wind."The other two are Taka Shin'etsu's pupil Fūgai Enchi (1039-1712), who does not seem to

have been a painter, and Fūgai Honkō (風外本高 (1779-1847), who painted in both Zen and Nanga styles

and was strongly influenced by the works of lke Taiga (1723-1776).

The name "Fūgai." which these three monks shared, signifies an existence beyond the cares of everyday life.Fūgai Ekun was born in the small village of Higishio, not far from the famous Tokaido

Road that connected the new capital of Edo (Tokyo) with the old capital of Kyoto.

Higishio was an agricultural village in the mountains ofKanagawa province, and Fūgai

probably came from a farming family. At the unusually early age of four or five he

entered the village temple, Kansō-ji, of the Shingon sect. After a few years,

Fūgai moved to the larger temple Chōgen-ji, several valleys distant, where he

formally joined the Sōtō Zen priesthood.

At about the age of sixteen Fūgai traveled to the leading Sōtō temple in

eastern Japan, Sōrin-ji (in present-day Gumma prefecture), where he studied

under Jizen Gen'etsu (d. 1589) and Ketsuzan Gensa (d. 1609). Since there is an

early Daruma scroll in the Sōrin-ji collection that undoubtedly Fūgai was able

to see, it is possible that he began to develop his interest in brushwork at this

time. After more than a decade of Zen training, Fūgai left the Sōrin-ji,

perhaps in 1596, to begin an extended period of journeys in search of further

Zen experience, including the ritual challenge of questioning and being

questioned by masters of different temples. This form of pilgrimage was

common, but few monks maintained an unsettled way of life for as long as

Fūgai; he traveled for more than twenty years. Although this period of his life

is almost undocumented, one source suggests that Fūgai visited the noted

Rinzai monk-painter Motsugai Jōhan (1546-1621) and his pupil lsen Shūryū

(1565-1642). Sojourns at Rinzai temples may well have stimulated Fūgai's

interest in brushwork, since the Sōtō sect had little history of artistry.In 1618, at the age of fifty, Fūgai accepted an invitation to become abbot of

Jōgan-ji, a small Sōtō temple in Sagami province not far from Odawara

Castle. He did not find this position to his liking, however, and after a few

years he abandoned the temple to live in caves in the nearby mountains.

For this reason he is often referred to as 「穴風外」 "Ana Fūgai'' (Cave Fūgai).

What made Fūgai decide to turn his back on the traditional Zen way oflife and

adopt such a primitive existence? Was he influenced by tales of eccentric Chinese

monks and Taoist recluses of the past? Was he unhappy at the increasing

materialism of Japanese culture or suspicious of the new shogunal government,

which did not hesitate to intervene in religious matters? While there

were often social and political pressures weighing upon abbots of major

monasteries in urban settings, at Jōgan-ji Fūgai would certainly have been able

to administer his small country temple without much outside interference.

Perhaps the position was not stimulating enough; more probably, Fūgai

needed to live completely on his own in order to achieve his Zen goals.

Judging from the fierce and lonely spirit he displayed in his paintings and

poetry, he was ready for greater challenges than temple life offered.

Whatever his reasons may have been, Fūgai left Jōgan-ji; with only a single

bowl and his monk's robe, he moved to the nearby mountains. At first

he lived in a double-cave that had been a prehistoric burial site.

Nestled low in the foothills of the mountains near the small village of Tajima,

this cave still exists within a copse of trees and bushes. After a year or two,

Fūgai moved to another small cave in the Kamisoga mountains, which is now

almost forgotten in a grove of tangerine trees halfway up a mountainside; in

Fūgai's day the mountain was covered by trees and brush. He may have chosen

the cave because its opening faces south to a clear view of Mount Fuji.

By living in a cave Fūgai emulated Darurna, who is supposed to have

meditated in front of a wall for nine years. Referring to his senses, which

would only delude him, Fūgai wrote that he kept "his windows deeply shut."

What food he could not gather himself he obtained from local villagers. It is

said that when he needed rice he would brush an ink painting of Daruma and

hang it outside his cave. Anyone who wished could then leave rice and take

the painting home. These works were venerated by local farmers and woodgatherers

as expressions of Fūgai's extraordinary personality; many of his

paintings still remain in local village houses, darkened by smoke from incense

and cooking fires.

While living this simple and primitive existence, Fūgai seems to have

reached a state of empathy with nature comparable to that of the "immortals"

of Chinese Taoism. He wrote in his poems that "after surveying the world, it

is difficult to leave this valley," and "even when fire threatens, I will not move

from my mountain home; Wind stirs the peaceful locust tree, underneath it I

dream." In another quatrain, Fūgai wrote that he was distracted from his Zen

practice only by visitors:This old monk meditates and rests in the empty mountains

In loneliness and stillness through the days and nights.

When I leave the pure cliffs, I am distracted by callers--

The world of men is first and always the world of men.It is difficult to establish a chronology of Fūgai's art because so few of his

works are dated; one painting remains, however, that must have been done

either while he was still at Jōgan-ji or shortly thereafter, during his early years

of cave dwelling. The intensity that is the hallmark of his brushwork can be

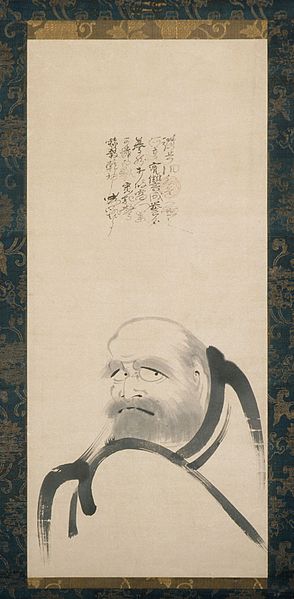

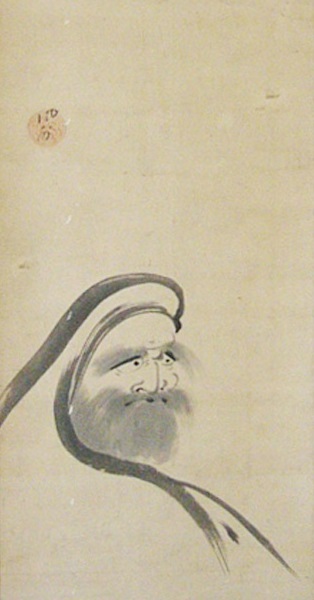

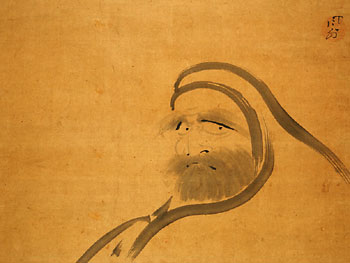

seen in this small portrait of Daruma:

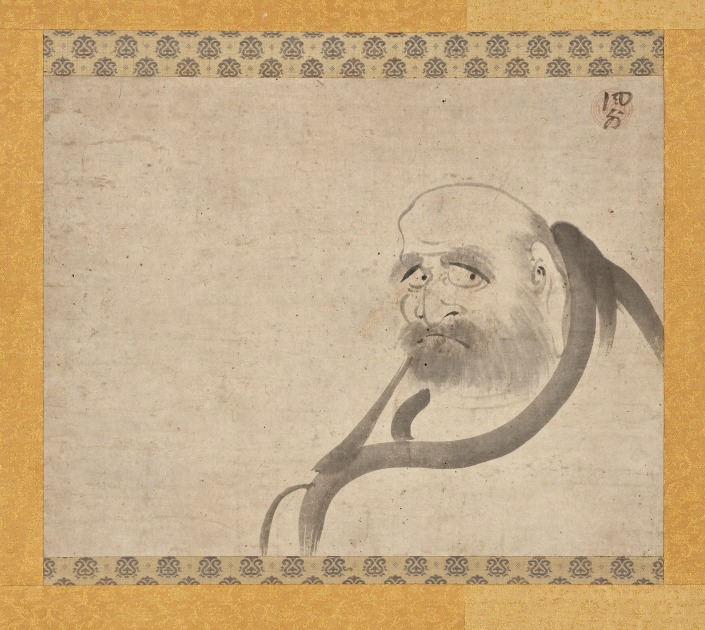

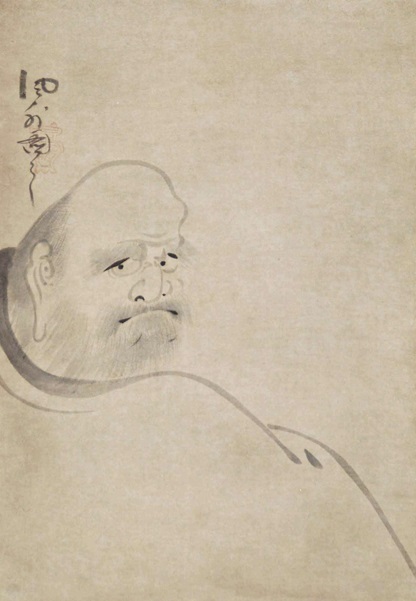

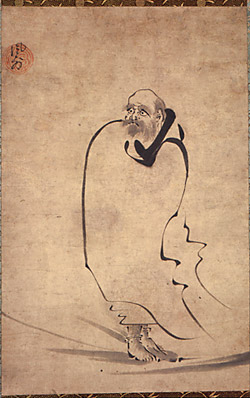

Four thick gray strokes, the upper two reinforced with black, define the

patriarch's hood and robe. Within the cell created by these broad strokes, thinner

gray lines depict Darurna's forehead, eyes, nose, and cheeks, while scratchy

gray brushwork suggests his thick eyebrows, mustache, and. beard. Black

accents bring the Zen master to life, accentuating his tilting eyelids, bold,

staring eyes, wide nostrils, andfrowning mouth. These few brush strokes

are all Fūgai needed to create a personalized image of remarkable power.

The painting is also unusual in that some drops of gray ink were spattered

upon the paper. Although accidental, two of the gray dots have fallen into

the patriarch's beard and one into his eye, adding a distinctive and slightly

humorous touch to the work. In Fūgai's painting, Daruma is portrayed as a

human being, not an icon, and yet the patriarch's spiritual strength is clearly

conveyed.

The painting bears a poetic inscription by Nisshin Sōeki (also known as

Sōeki Gashō; 1557-1620), whose death date allows us to establish the portrait

as Fūgai's earliest known work. A monk from Kanagawa, Sōeki became the

162nd abbot of Daitoku-ji in Kyoto; late in his life he retired to his homeland,

where he lived in the Ten'yū-an subtemple of Sōun-ji, not far from Fūgai's

temple and caves. Sōeki's inscription, in small, sharply defined regular script,

is composed within a shape that creates an upside-down mirror image of

the form of Daruma, while his signature extends down to the lower left.

The poetic quatrain suggests the total concentration needed to achieve

enlightenment:Notch the arrow of emptiness

To shoot the hawk of ultimate meaning;

If you're not right on target,

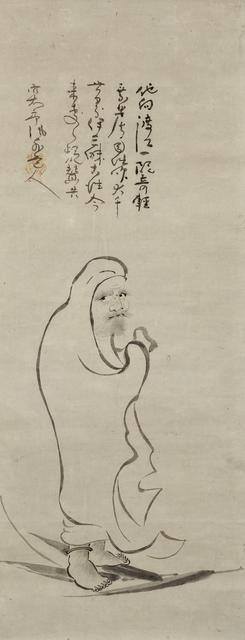

You will be deceived by this barbarian monk.Fūgai's solitary life, centered in meditation, further refined the Zen spirit

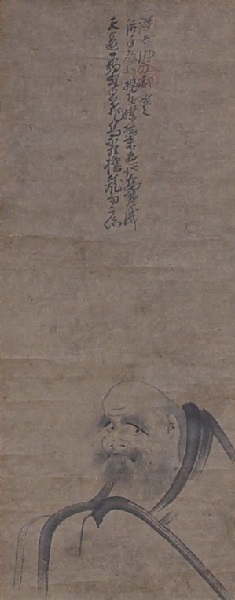

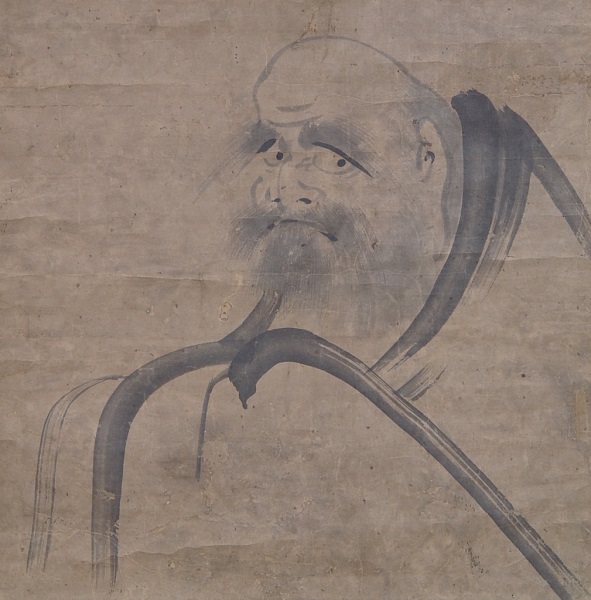

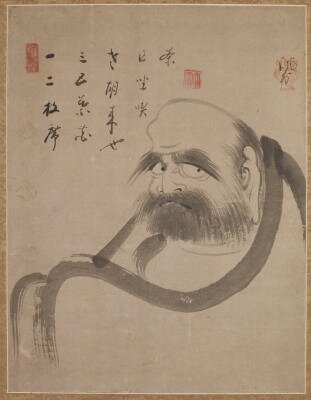

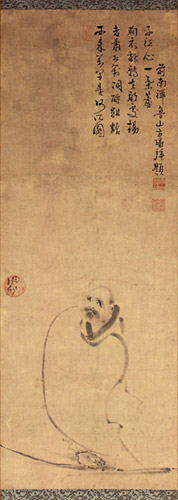

transmitted so clearly in his brushwork. He brushed a number of self-portraits,

which usually show him leaning on a staff and looking very much

like Daruma, an indication of Fūgai's sense of identification with the patriarch.In one such work, Self-Illumination:

Fūgai utilized his favored combination of broad gray outlines for the robe, thinner

gray lines for the head and face, and black accents for drawing attention to the mouth,

nose, and especially to the eyes. By the placement of these accents, the monk created

an individualized self-portrait unlike any that had come before. His expression is

a mixture of ferocity and sadness. He is inward-looking, wise, and lonely, as

though he had taken all of life's burdens upon himself. The broad lines of his

robe seem to encircle his face, emphasizing the sense of his spirituality.

The calligraphy in Fūgai's unique curvilinear style adds greatly to the total

artistic effect. The composition of the title, poem, and signature both hovers

over and balances the figure. The calligraphy's rhythmically fluctuating thin

lines contrast with its thicker brushstrokes and gray ink tones, just as in the

painting. Occasional strong diagonals point down to the left and to the right,

until the final swing of the brush leads directly to the figure. Fūgai's poem

offers us an additional insight into his character:Yearning for friends ill my rocky cave, I am captivated by the singing of small birds;

The wind entering deep into the grotto mingles with the voice of the stream.

Awakening from a dream, this hermit exists beyond the world--

A quiet life, off by myself, fulfills my spirit.If this work did not bear the title of "Self-Illumination," we might wonder

whether it was meant to portray Fūgai or Daruma; here, the two become one.

Although there is little specific information about Fūgai during his cave

years, one anecdote relates that a respected monk from Edo named Bundō

visited Fūgai. Seated high on a cliff, the two engaged in conversation all

morning until it was time for a midday meal. They then descended to a hearth

where Fūgai cooked some rice. There was only one bowl, so Fūgai served his

guest's food in a dried animal skull. This was shocking to Bundō; he exclaimed

that the skull was unclean and he would not eat from it. Fūgai chided

him, at which point Bundō left without another word and never visited again.

The idea of Fūgai serving rice in an old dried skull is a clue to his independent

spirit in keeping with the depth of expression revealed in his self-portrait.

Fūgais life was extremely spartan. Both of his caves are just large enough to

stand upright in; the cave in the Kamisoga mountains has a raised rock floor

where he might have slept. This life-style lasted for less than a decade. The

story of an eccentric Zen monk living in a cave gradually spread through the

region; when Fūgai left the mountains in 1628, it was probably to avoid the

interruptions, no matter how respectful, of visitors. Shortly after he moved

away from the area, a group of local farmers installed three stones engraved

with inscriptions honoring Fūgai and his parents in the Kamisoga cave. As far

as we know, he never returned there.

Fūgai spent the next twenty-two years of his life in the mountain village of

Manazuru, about fifteen miles south of Odawara. This was a poor community

even by the standards of the time; most of the people earned their

living by fishing or by quarrying rock. At first Fūgai may have lived in a cave

or small hut, but he soon became friendly with the village headman, Gomi

Iyemon, who built a simple cottage for the monk next to the local Tenshin

shrine in 1630. This was to be Fūgai's home for the following two decades. His

friends were the village children, with whom he would play and for whom he

would paint. According to a well-known anecdote, one day when it began to

rain, Fūgai picked up a large, flat rock and held it over his head like an

umbrella. He then walked through the streets, to the children's joy and the

villagers' amazement. A folk song originated in Manazuru about this incident:Ame konkon futte kita

Tenshindō no bōsan ni

minokasa motte yukōThe rain has started to fall konkon--

Let's take a straw raincoat and hat

To the monk of Tenshindō.With his penchant for wandering, playing with children, and refusing

official positions in the Buddhist hierarchy, Fūgai resembled Hotei, the semi-legendary

monk and "god of good fortune." Identified as the Chinese monk

Ch'i-tzu from Chekiang, Hotei (Chinese: Pu-tai) died in the early tenth

century. After his demise he is said to have reappeared walking through the

area, a famous non attached being who predicted the weather, slept out in the

snow but was never covered with flakes, ate meat, and drank wine. Carrying

his huge bag (Hotei means both "cloth bag" and "round belly"), a staff, and a

fan, he became celebrated as the god of merchants (who believed that the bag

was full of goods) and children (whom he preferred to adults). He was

considered an incarnation of Maitreya, the Buddha of the future, and was

often depicted in paintings and sculpture. In Japan Hotei became a special

favorite of Zen artists, ranking next to Daruma as a traditional subject.

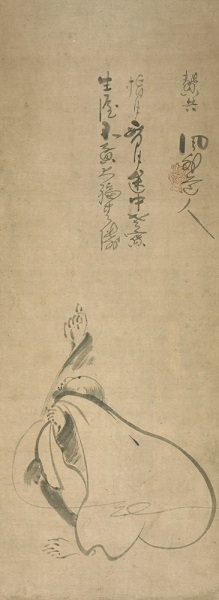

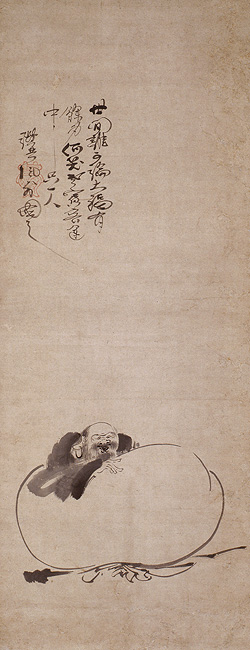

Fūgai depicted Hotei in a number of different guises. Often the roly-poly

monk is shown wearing a happy smile, but in Hotei Wading a Stream he walks

through the water with a sad expression on his face:

The image reminds us that Zen does not ignore happy or unhappy feelings but clings to

neither one. Gray ink tones have been reinforced with black, blurring effectively

on the robe, while the round shape of Hotei's head is echoed by the

bag, the fan, and particularly his round belly. From these circles, ripples of

energy spread out in vibrant pools, enlivening not only the figure but also the

empty space around him. Although there is no poetic inscription, the two

twisting lines representing the ties of his robe echo the calligraphy of Fūgai's

signature. Touches of black ink dramatize Hoteis face, particularly his eyes,

which are widely spaced, slightly tilted, and wondrously sad. In works like

this Fūgai transcended most painting of his time by giving a sense of personality

to his subject.

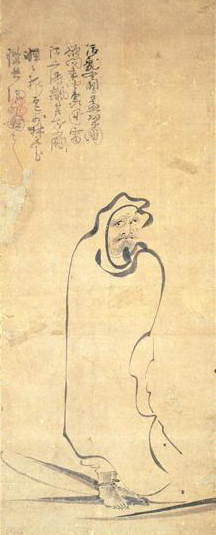

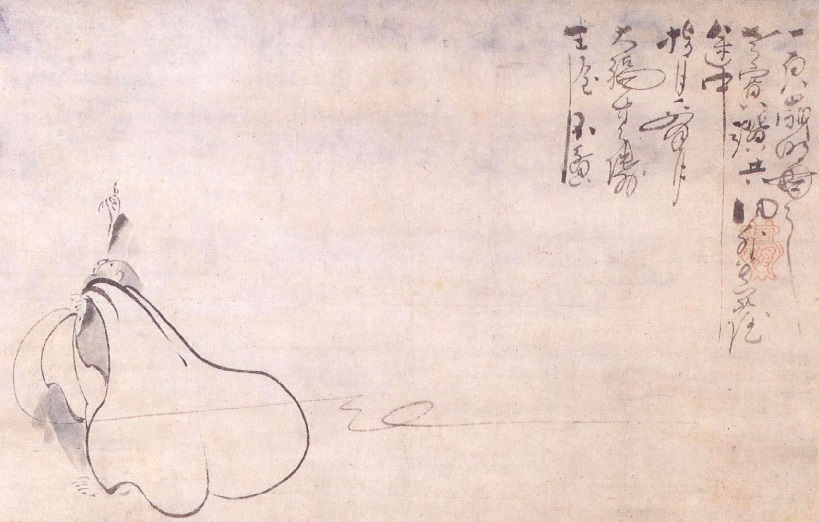

In Fūgai's Hotei Pointing to the Moon we see an image that in Zen

teachings carries the admonitions not to mistake the pointing finger for the

moon itself and to understand that moonlight is only a reflection, just as our

minds are reflections of thoughts, actions, and feelings. When, like a mirror,

we freely accept and release these reflections, the moon becomes a symbol of

life's treasures, which are actions and appreciations rather than possessions.

Fūgai himself was a master of the "three treasures" of the scholar and the

educated monk: painting, poetry, and calligraphy. Each is an important art in

itself, and combined they produce more than the sum of their parts. In Hotei

Pointing to the Moon Fūgai has adroitly arranged image and empty space and

employed calligraphy that echoes the brushstrokes of the painting. Not only

does the sweeping flourish of the bag-string cross the scroll horizontally, but

the rhythm of Hotei's pointing finger and the roundness of his sack are

repeated in the verticals and curves of the inscription.

These linear relationships within Fūgais works demonstrate that the most

meaningful Zen paintings go beyond free brushwork; they encompass the

formal traditions of an art that relies on composition, brushwork, and ink

tones. The intensity of Fūgais paintings ultimately derives from his inner

experience, but it is expressed through line, shape, and tone, each of which can

be analyzed and appreciated for its artistic merits. Fūgai not only had his depth

of experience to communicate but also a full command of the brush with

which to express his Zen spirit. Here, the soft, thick gray brushstrokes that

suggest Hotei's robes curve in a reverse "S" shape but are divided by the

contrasting long, incisive strokes that define and surround the emptiness of

his bag. We can sense the balance and weight of the figure even as he points to

the sky. By creating points of emphasis over the gray ink with the slightest

touches of black, Fūgai has evoked an enlightened state of being. His poem

emphasizes how Hotei exemplifies the joys of non attachment:His life is not poor,

He has riches beyond measure.

Pointing to the moon, gazing at the moon,

This old guest follows the way.Needing no home, appreciating each moment, the legendary figure travels

through life with a smile. Is this how Fūgai himself lived? In three other

poems that he inscribed on paintings of Hotei, Fūgai further demonstrated his

intuitive understanding of this unique wandering monk:What moon is white, and wind high?

His life is just this chant of meditation.-

How can he smile so happily?

Do not compare him with others;

His worldliness is not worldly,

His joy comes from his own nature.-

Who in the world can discuss him,

With his oversize body full of good luck,

How laughable-- this old guest

Is the only one traveling the road.(Translation by Jonathan Chaves)

Hotei travels alone; perhaps because no one else understands his joy. He

smiles; it may be at his own laughable self. Fūgai's paintings and poems

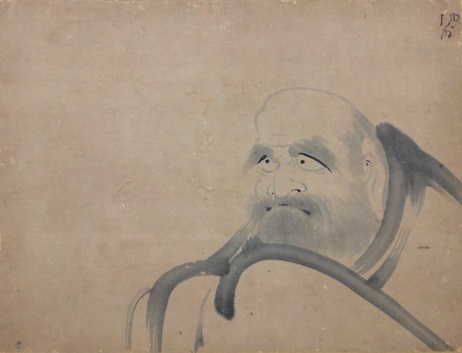

suggest the paradoxical nature of enlightenment.As well as representations of Hotei, Fūgai continued painting portraits of

the first patriarch. These follow tradition: in Daruma Meditating

the patriarch's head is bald and lumpy, his ears are long, and his hands are

clenched beneath his robe. This garment is depicted by strong dark lines with

"flying white," where the paper shows through the rapid, dry brushstrokes.

These create a bold contrast to the gray curving lines of varying width,

enlivened by black accents, that describe Darurna's forehead, nose, check, and

ear. It is the eyes, however, focused intently to one side, that seem to stare

deeply into us and will not let go.

What was Fūgai's intent in producing such fierce images? What did he wish

to communicate through his brushwork? In poetic inscriptions on Daruma

paintings, Fūgai emphasized the remarkable inner vision of the first patriarch:This old barbarian sat face to the wall,

Everyone in the Zen tradition is left confused.

One thousand years, ten thousand years--

Will anyone ever understand?-

This wall-gazing old barbarian monk

Has eyes that exceed the glo of the evening lamp;

His silence has never been challenged--

His living dharma extends to the present day.In his poems as in his paintings, Fūgai concretely expressed the understanding

that Darurna achieved enlightenment by total concentration of his spirit. In

another quatrain, Fūgai compared the intense meditation of the patriarch to

the ferocity of a hawk:High in the void, a hawk dances in the empty wind;

Sparrows cannot rely on the hedge for protection--

The hawk swoops down like a stone

And frightens every being throughout the land.The image of Darurna in Fūgai's poems is as fierce as in his paintings. The

patriarch is frightening and dangerous; the only way to understand him is to

match his spiritual concentration. Fūgai did not teach pupils in the usual Zen

style; but by living in a manner similar to that of the patriarch, he could

communicate through his art the intensity needed to reach enlightenment.

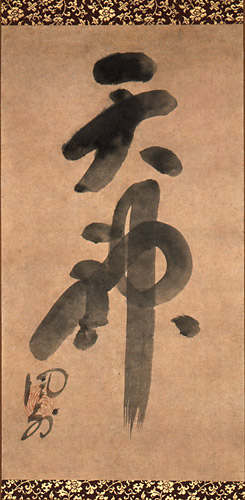

Remarkable as his achievements were in brushwork, Fūgai was not limited

to calligraphy and painting. His other artistic accomplishments included

carving his own seals from cherrywood; these bear legends such as Fūgai and

Fujin (No Person). While in Manazuru he also sculpted bold portraits of his

parents out of rock. Just as his brushwork emphasizes the nature of

ink and paper, Fūgai's sculptures convey a sense of the rock from which they

were carved. He retained the round boulderlike forms of the stones, which

evoke a feeling of massive strength and endurance. Furthermore, since many

people in Manazuru made a living by quarrying rock, the images also

increased the bond of solidarity between Fūgai and the townsfolk. A folk

superstition developed that if a child had whooping cough, prayers to the stone

images of Fūgai's parents would help to cure the disease. This belief continued

even after the sculptures were removed from Manazuru by the daimyo of

Odawara, Inaba Masanori (1623-1696), and taken to a temple in Edo.Although Manazuru was a poor mountain village, its scenic beauty occasionally

attracted visitors. In 1643 one of Japan's most important feudal lords.

Mito Yorifusa, visited Manazuru and stopped for lunch at the Gomi home.

Fūgai was present at this occasion and wrote a formal account of the visit.

noting that Yorifusa chanted poems and made a flower arrangement for his

host. As the most educated person in the area, Fūgai was called upon several

times thereafter to compose texts, probably at the behest of his friend Gomi. In

1645 Fūgai wrote the Iwaya engi ("A History of Iwaya") for the local Kibune

(Shinto) shrine, and in 1650 at the age of eighty-two he wrote out two more

texts in hand-scroll form. The first was the Kibune Dai-myōjin engi (History of

the Grand Deity of Kibune) and the second was a list of the names of donors to

the shrine. Fūgai also brushed a set of twelve panels of large calligraphy,

probably for the local temple, Ryūmon-ji, where they now remain. These

convey proverbial phrases such as "Always leave a few grains of rice for the rat:

for the sake of the moth don't burn the lamp," and "When the road is long, we

learn the strength of the horse; as years pass, we understand the human heart."

Fūgai also wrote out the chant "Namu Amida Butsu" several times for devotees

of Pure Land Buddhism. Despite his reclusive tendencies, it is clear that he

was kind and helpful to the villagers of Manazuru, and his firm commitment

to Zen did not prevent him from encouraging other Buddhist or Shinto religious

beliefs. He also brushed a few secular texts from time to time. One calligraphy

states that "one thousand barrels of refined wine do not equal a cup of

thick sake," suggesting that Fūgai may well have been fond of the older form

of rice wine, which was not strained and purified.

In 1648 Gomi built a shrine called Temangu for Fūgai next to his rustic

cottage. Fūgai thereupon erected a stone death stupa and inscribed it with a

poem about himself:Leaves fluttering before the wilnd--

How to convey their splendor?

I know this stone pagoda with my entire body,

And laugh at the changes of earthly life.This poem is difficult to translate and interpret, but it expresses Fūgai's

understanding of life's transitions, which are both beautiful and laughable

when seen from the perspective of nonattachment.

One of the most famous stories about Fūgai, often repeated but unverified.

concerns a visit to Manazuru by the daimyo Inaba Masanori and the young

monk Tetsugyū (1628-1700). It is known that Masanori came to Manazuru in

1645 and twice in 1648; if the visit with Tetsugyū actually took place, it was

probably in 1650. At this time Masanori was twenty-seven years old, Tetsugyū

twenty-two, and Fūgai eighty-two. According to the story, Tetsugyū

questioned Fūgai about the Zen life. Fūgai replied, "Becoming a monk is easy:

becoming a monk is hard," a cryptic way of saying that entering the priesthood

may be easy, but truly living a spiritual life is very difficult.

Tetsugyū was supposed to have been inspired by this statement, and after

Fūgai's death he had a notable career as one of the leading Japanese monks of

the Chinese-derived Obaku sect (see Chapter Three). During his many

travels, Tetsugyū maintained his connections in the Odawara area, consulting

with Inaba Masanori at Odawara Castle in 1660 and visiting the Gomi family

in Manazuru in 1667. In 1669 Masanori invited Tetsugyū to become the

abbot of Shōtai-ji, a temple built in Odawara, and Tetsugyū later also opened

Kōfuku-ji in Edo for Masanori. It was at Kōfuku-ji that Fūgai's stone portrait

of his parents were maintained in a special shrine. Thus, whether or not Fūgai

and Tetsugyū ever actually met, their lives were intertwined.

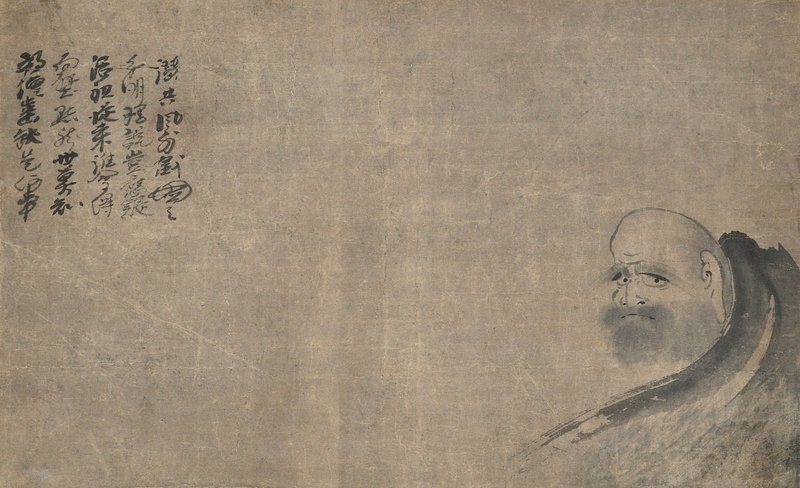

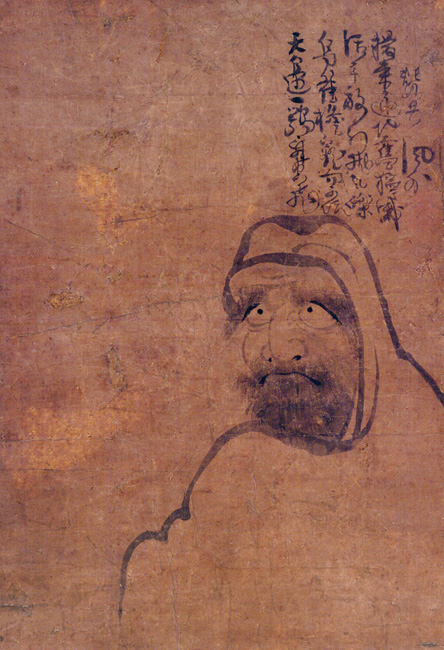

One of Fūgai's largest and most important extant scrolls, Daruma Crossing

the River, bears an inscription by Tetsugyū dated to the winter of

1667, which by the Japanese calendar was the one hundredth anniversary of

Fūgai's birth. Tetsugyū's fluent running script shows the influence of the late

Ming dynasty calligraphic style, which had been brought to Japan by Chinese

Obaku monks:The water in the Liang River becomes shallow,

There is no place to moor a large boat.

Watch him go by on a single reed--

His legacy continues to increase and increase.Fūgai's paintings, which were given away to villagers and children, are

usually small in size and often exist today in a poor state of preservation.

Daruma Crossing the River provides an unusual example of a large work by the

artist in excellent condition. The subject is traditional: with his robe extending

to form a hood over his head, Daruma crosses a river on a reed. As a rule,

Zen has had little use for miraculous deeds, stressing instead the enlightenment

of the everyday world. In this case, the Chinese character that had once

meant both "reed boat" and "reed" lost its first meaning over the course of

time. This inspired the idea that Daruma had crossed on a reed rather than in a

reed boat, giving rise to the legend here depicted.

Fūgai always painted Daruma staring intensely, but these portraits have

subtle differences. Here the two lines of the neck echo those of the forehead,

while the heavier gray lines under the chin resemble the Chinese character for

"mind" or "heart." These lines create a frame for the face, which is rendered in

pale gray ink dramatized by Fūgai's uniquely expressive dashes of black. The

body of the patriarch, by contrast, is merely the empty paper surrounded by

thick, sweeping lines. Daruma's hairy feet add a touch of the earthy Zen

humor that is often seen in the art of Edo-period monks.

Fūgai's last years were spent away from Manazuru. Masanori was fascinated

by the reclusive Zen master, whom he twice invited to live at Odawara

Castle; in 1651 Masanori extended a request that the old monk was unable to

refuse. Moving from his life of "one cup and one robe" in a village hut to

the splendors of a daimyo's mansion, Fūgai soon realized that Masanori lived

a dissolute life. In the Muromachi period, when Zen was so closely allied

with the elite, a monk might have remained in the castle, but in the seventeenth

century Fūgai had no reservations about following his own path. One

night after a lavish banquet attended by several concubines of the daimyo,

Fūgai wrote a poem on a blank screen and left the castle. In this quatrain he

made it clear that Masanori was not ready for the direct transmission of Zen:You govern an entire province--

I merely exist beyond the wind ["fū-gai"].

You were not a proper host for this unexpected guest;

Expedient teachings, not ultimate truth, are right for you.In order to avoid the daimyo, and perhaps fearing that Masanori's wrath

might fall upon his friends in Manazuru, Fūgai did not return to the village

but wandered into the mountains of Izu province. According to legend,

Masanori soon realized his mistake and hastened to Manazuru in order to ask

Fūgai to return, only to find him gone. Fūgai stayed at Chikukei-in, a small

temple in the town of Baragi in Izu, for the next two or three years. His death,

like his life, was unique. As related in one of the earliest accounts about him,

he walked into the countryside near Ishioka on the shores of Lake Hamana.

Coming across some village workers, he paid them to dig a deep hole. When

they were finished, he examined it and said he wished to be buried there. He

climbed into the hole and died standing up, at the age of eighty-six.

Fūgai chose to live a solitary life. Unlike most notable monks, he did not

accept Zen students, did not lecture on Zen texts, and had no spiritual heir.

Although he must have had a remarkably deep grasp of Zen, his only teachings

are found in his poetry, calligraphy, and paintings. These works, revered

for generations in local homes in the Sagami and Manazuru areas, have only

slowly come to public attention, but they are now highly admired by connoisseurs

of Zenga. It is the intensity of vision conveyed in his brushwork that has

become Fūgai's legacy to the world.

ZEN POEM

in: ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews

Translated by Lucien Stryk & Ikemoto Takashi [ 池本喬, 1906-1980]

Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963

FUGAI (17th century, Soto)

Only the Zen-man knows tranquillity:

The world-consuming flame can't reach this valley.

Under a breezy limb, the windows of

The flesh shut firm, I dream, wake, dream.

Daruma (Bodhidharma)

by Fūgai Ekun

Half-body Daruma

Hanging scroll, ink on paper

48.3 x 33 cm

Daruma Crossing the River

Hotei (Bodai) Pointing at the Moon

by Fūgai Ekun

Smiling Hotei (Bodai)

by Fūgai Ekun

96.5 x 30.5 cm

Kanzan & Jittoku (Hanshan & Shide)

by Fūgai Ekun

Lazy San, the potato monk

by Fūgai Ekun

Hanging scroll, ink on paper

32.7 x 44.0 cm