ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

寒山拾得 Hanshan & Shide (b/t 730-850)

(Rōmaji:) Kanzan & Jittoku

(English:) "Cold Mountain" & "Pick-up or Foundling"

(Magyar:) Han-san, „Rideg-hegy” & Si-tö, „Lelenc”

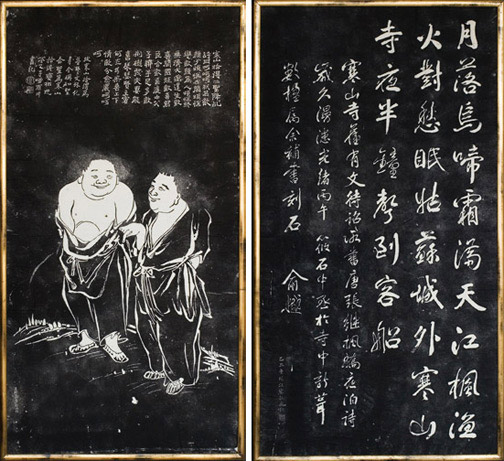

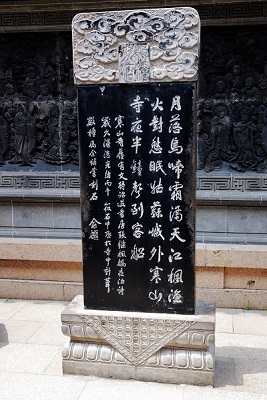

寒山拾得像石刻 / [唐仁齋所作] Hanshan Shide xiang shi ke / [Tang Renzhai suo zuo], 69 x 130 cm

The stonerubbing is from an engraved stone stele in the Hanshan Temple in Suzhou.

Carved by 唐仁齋 Tang Renzhai some time in the years 1875-1908.

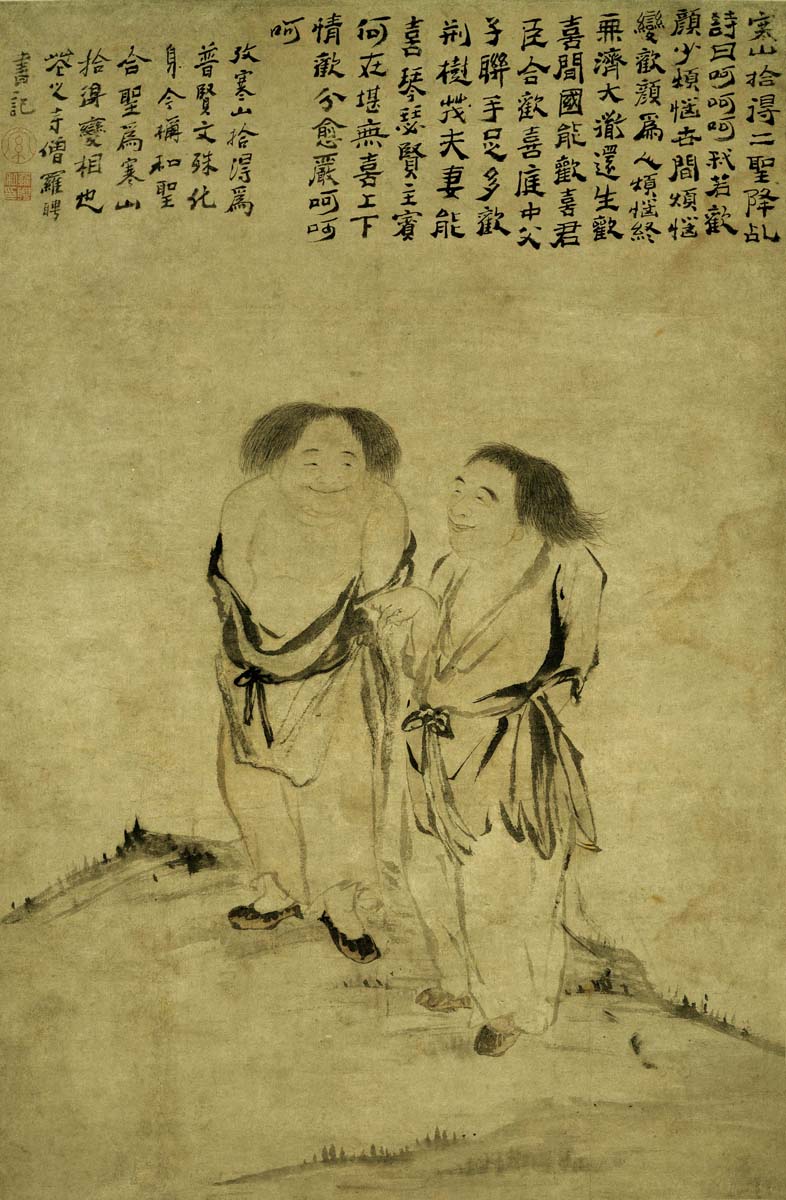

寒山拾得 Hanshan and Shide

Painting by 羅聘 Luo Ping (1733-1799)

Hanging scroll; ink and watercolor on paper,

78.74 x 51.75 cm

Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City

(Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust)

![]()

Han-shan and Shih-te stonerubbing

The well known stonerubbing that has given most of us the visual of Han-shan and Shih-te, is based on a painting by 羅 聘 Luo Ping (1733-1799). The painting is now in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City. The stonerubbing is from an engraved stone stele in the Hanshan Temple in Suzhou. Carved by 唐仁齋 Tang Renzhai some time in the years 1875-1908. The stele is larger (125 x 60 cm vs the paintings 78.7 x 51.8) with some minor differences in the details.

http://nelson-atkins.org/collections/iscroll-objectview.cfm?id=29477

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luo_Ping

Pair of Chinese Rubbings

Terebess Collection

This pair of stonerubbings are from an engraved stone stele in the Hanshan Temple in Suzhou.

One of the rubbings show the figures of the monks Hanshan and Shide (known in Japan as Kanzan and Jittoku).

These particular figures of Hanshan and Shide were originally painted by Luo Ping, one of the Yangzhou Baguai (the "Eight Eccentrics"). The original painting is in the collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (http://www.nelson-atkins.org/art/CollectionDatabase.cfm?id=29477&theme=China). The painting was carved into a stone stele at Hanshan Temple in Suzhou some time in the years 1875-1908 by Tang Renzhai.

The calligraphy panel is a Tang Dynasty poem, "A Night Mooring by Maple Bridge" written by 張 繼 / 张 继 Zhang Ji, brushed by Qing Dynasty calligrapher 兪 樾 Yu Yue (1821-1901). The poem describes the melancholy scene of a dejected traveller, moored at night at Fengqiao, hearing the bells of Hanshan Temple:

楓橋夜泊 張継

月 落 烏 啼 霜 滿 天

江 楓 漁 火 對 愁 眠

姑 蘇 城 外 寒 山 寺

夜 半 鐘 聲 到 客 船

Fengqiao ye bo Zhang Ji

yue luo wu ti shuang man tian [an]

jiang feng yu huo dui chou mian [an]

gu su cheng wai han shan si

ye ban zhong sheng dao ke chuan [an]

While I watch the moon go down, a crow caws through the frost;

Under the shadows of maple-trees a fisherman moves with his torch;

And I hear, from beyond Suzhou, from the temple on Cold Mountain,

Ringing for me, here in my boat, the midnight bell.

The poem is still popularly read in China, Japan and Korea. It is part of the primary school curriculum in both China and Japan. The ringing of the bell at Hanshan Temple on Chinese New Year eve is a major pilgrimage and tourism event for visitors from these countries.

楓橋夜泊 Zhang Ji's Poem: A Night at Maple Bridge

http://collection.imamuseum.org/artwork/70690/

The calligraphy records a famous poem by the Tang dynasty poet Zhang Ji 張継 (700s):

月落烏啼霜満天・江楓魚火対愁眠・故蘇城外寒山寺・夜半鐘声到客船

A crow cries as the moon sets in a sky filled with frost

The fires of fishing boats make the red maples glow, and I fail to sleep in my grief and sadness

From the Hanshan Temple outside the ramparts of Suzhou

Peals of its bell roll through the night to reach my boat

The poem paints a picture of despondent solitude pierced by striking beauty. Zhang Ji had set out on a boat trip after failing the national civil service examinations. As a model Tang poem it is studied in elementary school in China, Korea, and Japan.

The smaller script explains that a badly eroded stone monument with this poem written in the calligraphy of the great Ming dynasty literatus Wen Zhengming (1470–1559) had stood at Hanshan (Cold Mountain) Temple in the suburbs of Suzhou. In 1906 Yü Yüeh (1821–1906) was ordered by the governor of Jiangsu to rewrite the poem. The smallest script dates the rubbing to 1925.

Links:

http://www.robynbuntin.com/Chinese-Painting-Drawing-Pair-of-Chinese-Rubbings-p/9828.htm

http://trove.nla.gov.au/version/15103586

http://maniwa-circle.at.webry.info/200904/article_14.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zhang_Ji_%28poet_from_Hubei%29

http://www.360doc.com/content/13/0112/14/1726391_259725052.shtml

https://www.google.hu/ search

What is a rubbing?

Inscriptions:

There is no civilization that has relied as much as the Chinese on carving inscriptions into stone as a way of preserving the memory of its history and culture. Records of important events were inscribed on bone and bronze as early as the second millennium B.C., and brick, tile, ceramics, wood, and jade were also engraved to preserve writings and pictorial representations; but the medium most used for long inscriptions was stone.The most extensive of several large projects to preserve authoritative texts was the carving of the Buddhist canon on 7,137 stone tablets or steles—over 4 million characters—in an undertaking that continued from 605 to 1096. Earlier, from 175 to 183, the seven Confucian Classics in over 200 thousand characters were carved on 46 steles, front and back, to establish and preserve standard versions of the texts for students, scholars, and scholar-officials of the Eastern Han dynasty. The Confucian Classics were also inscribed by six successive dynasties, the last engraving, by the Manchu Ch'ing dynasty, at the end of the eighteenth century. At sacred sites, cliffs and rock faces were also used for large religious inscriptions.

Rubbings:

By the beginning of the seventh century, or perhaps much earlier, the Chinese had found a method of making multiple copies of old inscribed records, using paper and ink. Rubbings (also known as inked squeezes) in effect “print” the inscription, making precise copies that can be carried away and distributed in considerable numbers.To make a rubbing, a sheet of moistened paper is laid on the inscribed surface and tamped into every depression with a rabbit's-hair brush. (By another method, the paper is laid on dry, then brushed with a rice or wheat-based paste before being tamped.) When the paper is almost dry, its surface is tapped with an inked pad. The paper is then peeled from the stone. Since the black ink does not touch the parts of the paper that are pressed into the inscription, the process produces white characters on a black background. (If the inscription is cut in relief, rather than intaglio, black and white are reversed.)

This technique appeared simultaneously with, if not earlier than, the development of printing in China. Many scholars contend that block printing derived from the technique of making impressions with carved seals: in printing, a mirror image is carved in relief on a wood block; the surface that stands in relief is then inked, and paper pressed onto it—the reverse of the method used for making rubbings.

A rubbing, by accurately reproducing every line of the inscription in a white impression on black ground, provides a sharper and more readable image than the original inscription or a photograph of the original. The advantage of this technique is that it may be applied to any hard surface, including rock faces or cliffsides, pictorial reliefs, or even bronze vessels and figurines. As long as the object inscribed is in good condition, a rubbing of it can be made, regardless of its age or location. And by providing an accurate replica of the surface of a given inscription or relief, a rubbing gives the scholar, and especially the student of calligraphy, insights that simple transcriptions or freehand copies, subject to scribal errors and the copyist's skill, cannot.

Rubbings made a century ago preserve a far better record of the inscription than the stone itself, which might have suffered from natural erosion, not to mention damage caused by having been tamped in the process of taking thousands of rubbings. Early rubbings, therefore, are invaluable sources, preserving impressions of countless inscriptions now defaced or completely lost. Paradoxically, it is paper, usually thought of as a fragile medium, that preserves unique copies of inscriptions that were conceived of as permanent records in stone.

For at least a thousand years, scholars and connoisseurs have colleted rubbings, pressing seals of ownership on them as they do on paintings, calligraphy, and other prized objects in their collections. The East Asian Library's collection includes rubbings with collectors seals from as early as the seventeenth century, authenticating not only the age of the rubbings, but also the inscriptions from which they were taken.

Content of Inscriptions:

The scope of the content of inscriptions is encyclopedic, ranging from canonical texts sanctioned by the emperor to personal epitaphs and eulogies. Inscriptions, characteristically those on large upright stone slabs or steles, often provide historical information unavailable elsewhere, paying tribute to local personages by setting down their careers and deeds, or recording local events, military campaigns and victories, the establishment or reconstruction of temples, charitable subscriptions to religious institutions, hospitals, and orphanages, and meetings of guilds. They are often unique sources of information about local matters and persons, since the official histories and dynastic compilations heavily favor imperial affairs and the practice of statecraft.As sources for research in textual criticism, rubbings provide incontrovertible evidence that can be accurately dated. They provide variant readings and, in some cases, whole passages that have been dropped in the transmission of a published text or manuscript. These variants are especially important since the whole process of textual editing, collation, publishing, and transmission was governed by the dictates of orthodox Confucianism or other systems of thought and religion. Early inscriptions are usually more reliable than documents preserved in printed or manuscript form. Texts inscribed in stone or metal are not easily altered to reflect change in official policy or thought; this is especially true of inscribed texts only recently uncovered by archaeologists.

For the study of the history of writing and calligraphy, from the earliest script on shell and bone down to the running and cursive styles of later masters, inscriptions are irreplaceable sources. They trace the evolution of writing, century after century. Since the early dynasties, too, inscriptions have been carved in stone to preserve examples of the styles of great calligraphers. Rubbings of engraved models of calligraphy, known as fa-t'ieh 法帖 are the most widely reproduced and consulted genre of rubbings in China, Japan, and Korea today.

Glossary:

拓片 tàpiàn, tuò piān: rubbings from a tablet

拓印 tà yìn: stone rubbing (to copy an inscription)

法帖 fǎ tiē: rubbings of engraved models of calligraphy

![]()

Kőpacskolat - ta-pien