ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen index

« Home

Ten Ox-Herding Pictures (심우도)

Verse and commenary by 구산수련 / 九山秀蓮 Gusan Suryeon (1908-1983), aka Kusan Sunim

Translated by Martine Batchelor

Paintings by

"Living National Treasure" 석정스님 / 石鼎 Sŏkchŏng sŭnim

(1928-2012)

http://sungag.buddhism.org/tech22pe/read.cgi?board=essay&y_number=6

http://buddhapia.com/files/files_PDF/20041230/59-4.pdf

http://blog.daum.net/_blog/BlogTypeView.do?blogid=0MYJJ&articleno=8486402&_bloghome_menu=recenttext#ajax_history_home http://blog.naver.com/PostView.nhn?blogId=stardriver&logNo=60109665108&redirect=Dlog&widgetTypeCall=true

http://www.a-nous-dieu-toccoli.com/publication/2004/anthologiezen/anthologiezen1.html

http://www.koreanbuddhism.net/library/buddhist_essay/view.asp?article_seq=47&page=1&search_key=&search_value=

Sim-u do (Ten Oxherding Pictures)

"Sim-u," means "to look for an ox." This ox is set up as a

symbol of Buddha nature and the effort of finding this Buddha nature is divided

into ten steps which are to be sung, and this song is called the "Sim-u

song" or the "Sip-u song," and the pictures used to teach this

is called the "Sim-u do" or "Sip-u do."

"The Ten

Oxherding Pictures" consists of ten verses composed in the Korean

three-line sijo style. Written in vernacular Korean as opposed to classical

Chinese, the verses draw upon some of the imagery found in the traditional

verses of the Song-dynasty Chinese master Gaoan Shiyuan as well as Master

Kusan's [Kusan S?nsa, 1908-1983] own personal understanding of the pictures.

The verses are accompanied by oral commentary given to the monks attending the

winter meditation retreat at Songgwang Sa in 1972-73.

The way of Korean Zen by Kusan Sunim. Translated by Martine Batchelor.

New York, U.S.A.: Weatherhill, 1985, pp. 153-171.

Thus Samsara is transcended!

Blue mountains cross the waters

Like a sail before the wind.

Flowers bloom on a white rock:

It is spring outside the universe.

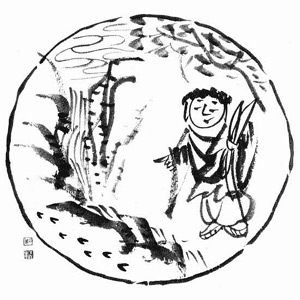

#1. Going out in search of the ox

High mountains,

deep waters, and a dense jungle of grass--

However much you try, the way to proceed remains unclear!

To alleviate this sense of frustration, listen to the chirping of cicadas.

This picture illustrates the feelings of someone who is practicing meditation for the first time. He is compared to a man in search of an ox who has just come outdoors in order to find it and then catch it with a rope. All of us who claim to be cultivating the Way usually have to pass through the difficult stage described here.

What are the pleasure we find in living in the world? These are to eat well, to wear good clothes, to have wealth, a good reputation, and a family, and to be able to sleep at ease. These are all basic physical concerns. However, what we call "cultivation of the Way" runs counter to these concerns. To live in the ordinary world is like flowing along with the current of a river. But to cultivate the Way is like swimming upstream against the direction of the current. Since beginningless time, the body has become accustomed to certain comforts. Now one suddenly decides to cultivate the Way through the practice of meditation.

And what is this like at the beginning? It is similar to finding yourself seated in front of a silver mountain or an iron wall. Thus, you encounter "high mountain, deep waters, and a dense jungle of grass." In the midst of all this, "however much you try, the way to proceed remains unclear." At this point you often wonder if the meditation is actually progressing at all. You start to consider various different ways of improving the practice. You find yourself at a complete loss as to what you should do.

After struggling and exerting themselves in this way for a while some people reach such a point of exhaustion that they consider giving up altogether. Although they have tried to practice, they cannot see any progress at all. But one should definitely not give up at this stage. Others will try "to alleviate this sense of frustration" in turning to another kind of practice. They may start to pray to the Buddha, repeat the Buddha's name, or recite some sutras. In such ways, their sense of frustration is alleviated somewhat. But actually they are just listening "to the chirping of cicadas." This does not mean that they literally go outside and listen to cicadas. It refers to their engaging in all those activities other than the practice of meditation in order to remove their feelings of frustration.

#2. Seeing the Footprints

A tangle of thorny

bushes: the faint murmur of running water.

But here and there are footprints --- is this the right path?

If you want to pierce its nose and tie it up, do not rely on someone else's

strength!

Your fundamental task is not that of trying in various ways to make things easier for yourself. If you intend to cultivate the mind, then you have to practice meditation. Yet even though you try, the meditation may not seem to progress. So you must remind yourself of the need to do such practice. In this way you will be able to check and control the distracted thoughts which pull you away from the meditation.

While you are struggling around with much hardship in the "tangle of thorny bushes," you may hear "the faint murmur of running water."This refers to the intrusion of certain external obstacles that occasionally interfere with the practice. The "faint murmur of running water" means that a mara is present. It may be that the people around you, your family, or some harmful friends start telling you that you may as well drop the idea of meditation since it doesn't seem to be getting you anywhere. But instead of listening to them you should carefully pay heed to the words of the Buddhas, the patriarchs, and other wise spiritual teachers. In doing this, the determination to persevere in the practice will grow in your mind.

When there is no progress, it is simply because you are not exerting sufficient effort yourself. To think otherwise is foolish. It is ridiculous to complain that no one is helping you when you yourself are not making any effort. Therefore, "if you want to pierce its nose nad tie it up, do not rely on someone else's strength!"

At this point you

may also start to notice that "here and there are

footprints." This may lead you to believe that now you are surely on

"the right path." Your task is to follow these footprints. You have

to proceed entirely on the basis of your own effort. Following these footprints

is like climbing a high mountain. Even if someone were to stand motionless at

the base of such a mountain just staring at it for ten thousand years, this

would be of no use at all. Step by step, he must follow the path to the top

himself. Of course, the one who walks quickly will get there before the one who

walks slowly. But no matter how you proceed, you have to go on your own.

#3. Seeing the Ox

Among willow

branches swaying in the spring breeze, an oriole is singing.

How can the sparrow experience his joy in calling to his mate?

Isn't the moonlight glimmering in the forest my home?

As you persevere in following the tracks of the ox, you finally begin to glimpse its tail now and again. In this way you first catch sight of the ox.

For a Korean, the oriole's song seems to say, "prettily, prettily, brush your hair and come over." It is this kind of mating song that I refer to in the verse. Yet "how can a sparrow," who cannot sing in the same way as an oriole, "experience the oriole's joy in calling to his mate?" Or how can a mere sparrow appreciate the wonderful time the golden oriole has in flying back and forth between the trees in pursuit of his mate?

After practicing for some time, one gradually starts to make progress. This is like peering at the distant moon and watching its light glimmering faintly in the forest. Such light is similar to the dim, flickering flow of a firefly. After the perseverece in meditation, occasionally a little insight will light up for a few moments like the glow of a firefly, die, light up again, and then die again. This is what is referred to by the line, "Isn't the moonlight glimmering in the forest my home?"

What you experience at this stage is something that you have never heard or seen before. Recognizing now that such a thing exists, you reflect that it is probably correct to keep going in this direction. At such a moment the mind has to make an important decision. In striving to maintain the hwadu, you have been advancing with great difficulty through a patch of thorny bushes. Now, in the midst of all this, a little moonlight starts to shine in the forest. Although you are encouraged to continue, this is still an uncertain and ambiguous time.

#4. Catching the Ox

Advancing with

difficulty; the ox's nose is pierced.

But this fiery nature is hard to control.

Dragged here and there, you stray through cloud-covered forests.

"Advancing with difficulty" means that you have to endure physical hardships without caring whether you live or die. It is at such a time that "the ox's nose is pierced." Yet even though its nose is pierced, its"fiery nature is hard to control." Whatever you do, the ox will always try to retreat quickly and run away. At times, though, the practice makes good progress, like that of a boat being pushed over ice. But after a while it ceases to be so easy and becomes as difficult as trying to force a horse to drink water when it doesn't want to. No matter how close you succeed in bringing the horse to water, it will keep avoiding it and running off. To control immediately the "fiery nature" of the ox is indeed difficult.

"Dragged here and there, you stray through cloud-covered forestes." In such a place the moon only shines sporadically. After you have caught the ox and pulled it toward youself with a great effort for a while, it will suddenly pull you off in another direction. You try to pull it back, but again it manages to drag you elsewhere. It goes on and on like this. Now you are struggling with great difficulty in a cloud-covered forest. The clouds are dense and the forest is thick. And you keep on straying here and there, catching hold of the ox and trying to pull it in your direction.

What exactly is this difficult time? It refers to the stage when the meditation is composed partly of the hwadu, partly of distracted thoughts, and partly of sinking into dullness. At this time, these three factors seem to be competing with one another: at some times you find yourself in a state of dullness, at other times beset with distracting thughts, and at other times concentrating on the hwadu. This is a vey difficult period because now you are really fighting with the ox.

#5. Herding the Ox

Fearing that it may

fall into a steep and perilous path,

You hold it tight with whip and bridle, and with the strength of both legs

firmly hold your ground.

Once past this critical moment, the ox comes following you.

It is at this stage that you learn to handle the ox in the right way. "Fearing that it may fall into a steep and perilous path" refers to the reaching of a certain stage in the practice when you are again beset with the doubt that no progress is being made. You reflect that in spite of your effort and enduring of hardship, the meditation is proceeding neither quickly nor well enough. Once more you are tempted to give up and instead study some sutras or recite some mantras. You might even contemplate becoming the abbot of a rich monastery or marrying a pretty girl and settling down to a worldly existence.

No matter how much effort you seem to be putting into the practice, it does not ripen as swiftly as you would wish it to. Soon all kinds of thougths start to trouble your mind. You wonder: By practicing in this way am I really getting anywhere? What am I doing? Now amara has entered your mind. You become aware of the danger that the ox "may fall into a steep and perilous path." This can be a very frightening time. So you have to "hold it tight with whip and bridel, and with the strength of both legs firmly hold your ground." Othewise it may actually break loose and stumble into the perilous path.

If you exert a great deal of effort for a while, then you will pass the "critical moment." Thereafter, "the ox comes following you." This is so because once you cross over that difficult point you will have succeeded in finally tameing the ox somewhat. Then you will realize that even if you went back to the world, it would be of no use. However well you feed and clothe the body, however comfortable and secure you can make it, at one moment it will become nothing but a heap of ashes. Although beforehand you were tempted by such things, now you decide to relinquish them. You also decide to renounce all worldly positions, wealth, and fame; the prestige you could have in the religious order by being an abbot; and the respect you would receive from lecturing on the Dharma, should you study the sutras. You now become determined to realize your own mind and become an accomplished being through the practice of meditation alone.

Once such a firm resolve has arisen in the mind, then you truly seize the abode of the hwadu. Now that the ox is being tamed in this way, the hwadu is firmly held and does not move. For such a person when he goes, it is practice; when he comes, it is practice. Having passed over the critical moment, the ox now obediently follows without your having to grab hold of it and pull it.

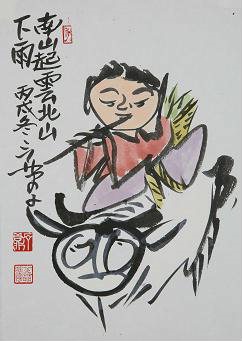

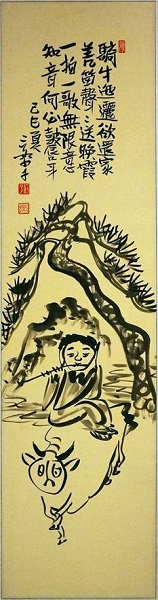

#6. Riding the Ox Back Home

Sitting astride the

ox, the noble person happily returns.

The sound of his flute mingles with the crimson sky: he has discovered the

garden of joy.

Who else could know about this endlessly pleasurable taste?

Once you have passed the critical moment and the practice has become somewhat more leisurely, then what is called "the single homogeneous mass" begins to emerge.

Now when you sit, the hwadu is simply there just as it is. Although you sit all day, you are unaware of sitting; although you eat all day, you are unaware of eating; even if you sleep all day and night, you will be unaware of having slept. Such is the state of the single homogeneous mass. When going, the hwadu is going; when eating, the hwadu is eating. The hwadu is no longer constantly appearing and disappearing.

When a person at this state sits, he is like a great unmoving mountain. When sitting, he just sits. He truly has the bearing of a mountain. Thus "sitting astride the ox, the noble person happily returns."

While riding the ox, you play the flute. You are now not at all concerned even if you go into a patch of mist or a field of thorns. The meditation has reached the point where you can practice even in the middle of a busy marketplace.

What does it mean to say that "the sound of his flute mingles with the crimson sky" and that "he has discovered the garden of joy"? When playing the flute while astride the ox, the person can now handle the ox in a leisurely fashion. Left to himself, the ox will just follow the way it has to go. Now that it has been tamed, however much you ignore it, it will no longer go anywhere that is not allowed. As for yourself, no matter whether you are sleeping or moving around, standing or lying down, no one else will be aware of the inner composure you have attained. At this sixth stage the practice really begins to develop with every step.

#7. Forgetting the Ox, the Man Rests Alone

Bright moon and

cool wind: what a splendid home!

Sitting all alone, he is with the ox gone away.

Even if you doze until sunrise, what use would a whip and bridle be?

The bright moon is rising and a cool wind is blowing: this is truly the best house of all. What a splendid home it is!

Now the ox is gone. First you had to make an effert to hold on to the ox; then, after some time, it began to follow you of its own accord. At this stage you do not have to pay it any attention at all. It proceeds correctly by along the way by itself.

"Even if you doze until sunrise... " This means that after sitting all night, unaware of the passing of time, while you are dozing with your back slightly bent, you quietly look up and cannot tell whether it is still nighttime or whether day has broken.

Many years ago in Haeinsa monastey, Kyongho Sunim would just sit quietly all day and night with his back slightly bent. Upon observing this, the sutra lecturer who lived below wrote him a note which said: "Since the venerable old monk is always dozing with his head down, it would seem that he has nothing better to do than to sleep." In reply, Kyongho Sunim answered: "Since there is nothing left for me to do, my only task now is to sleep." Because the ox is just as it should be, there is no need to whip it any more. Therefore, at this stage, even if you only doze, your practice will still keep advancing.

kyongho Sunim then added: "Sitting on the high seat, there is no need to think of this or that. One sits in samadhi without any thoughts at all." Such a person remains in samadhi irrespective of whether he is sitting or dozing. He continued: "Sitting without any thoughts, one abides in tranquillity and suchness. Thus one advances in one's natural state. So why do you disturb me by stirring up a little breeze? Instead of letting me sleep quietly in the forest, why do you make me float in the air?" At this stage you proceed entirely by yourself and need neither whip nor bridle.

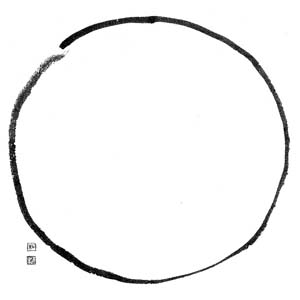

#8. the Ox and the Man are both Forgotten

Since even space

has collapsed, how can obstacles remain?

Could a snowflake survive inside a burning flame?

You cheerfully come and go: how could you not always laugh?

Both the ox and the man have now been forgotten, and you are sitting in silence and emptiness. At such a time "even space has collapsed." In our present state, all phenomena-- including space-- are experienced as existing. But at this time, space collapses. This is finally the moment of awakening. In order for the original nature to appear, it is necessary for even space to collapse.

"Could a snowflake survive inside a burning flame?" In the midst of such a state, the Buddhas and the patriarchs are of no use any more, for this is the time of "striking down the Buddha and striking down the patriarchs." Since the Buddhas and patriarchs are both of no use, how can you distinguish between ordinary and accomplished beings? Who would be ordinary? And who would be accomplished? Not even a single snowflake could survive here: the Buddhas and patriarchs are of no use to you now.

"You cheerfully come and go: how could you not always laugh?" It is fine to come and fine to go. It is fine to lie on you back and fine to lie on your belly. You may go as you please through the three unfortunate realms. Whether you are in hell, among the hungry ghosts, or amid the animals, everything is fine. If you find yourself in hell, in heaven, or in the Buddha lands, you can only laugh.

#9. Returning to the Original Place

My very own

treasure is recovered: all those efforts spent in vain!

It would be better to have been blind, deaf, and dumb.

The mountains and water are just as they are! So is the bird among the

flowers.

Finally you realize that you have recovered your very own treasure, which you had forgotten all about. When you quietly reflect on it, you recognize that all of the exertions you put into the practice were actually unnecessary. Now when you simply open you mouth, this is a teaching of Dharma; when you walk along, this is also a teaching of Dharma. Such a person is just like this: there is nothing else to it. There is nothing that is not Dharma. In fact, it would have been better, had you been blind, deaf, and dumb. Why? Because then you would not have been dragged into doing so many useless tasks. Now "the mountains and water are just as they are." Such is the Dharma teaching of inanimate things.

#10. Appearing in the Marketplace to Teach and Transform

Ragged and starving

you approach the market and the streets.

Even covered in dust, why would the laughter cease?

The bees and butterflies are happy because flowers have bloomed on a

withered tree.

In order to be of benefit to sentient beings, you are free to act in whatever way you see fit. You cultivate the way of the bodhisattva in wandering here and there through the steets and marketplaces. You perform the deeds of a bodhisattva: if someone asks you for whatever you are wearing or eating, you simply give it to him. Whatever you do, it is fine. If circumstances are favorable, you smile; and if circumstances are unfavourable, you still smile. With a laugh you take things as they are--like a fool! At this time, flowers have bloomed on a withered tree. Thus, whatever such a person does, he is pleasing to all sentient beings.