ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen index

« Home

![]()

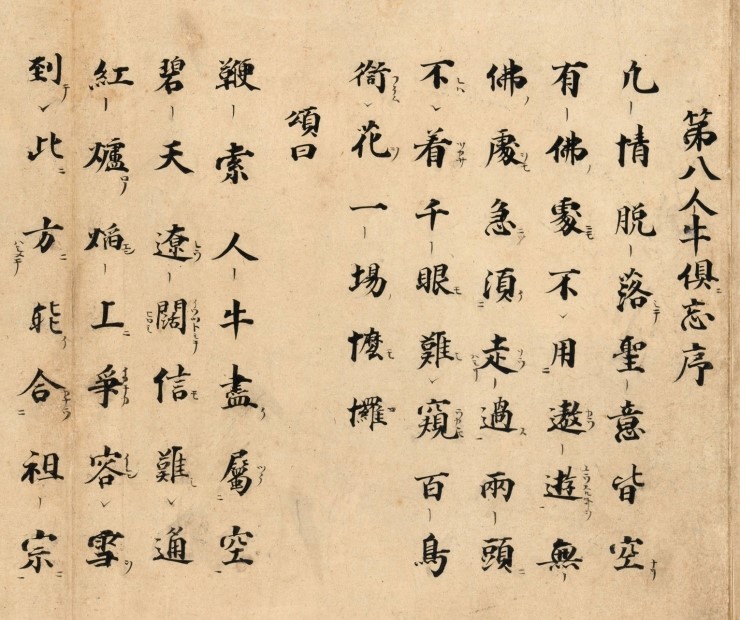

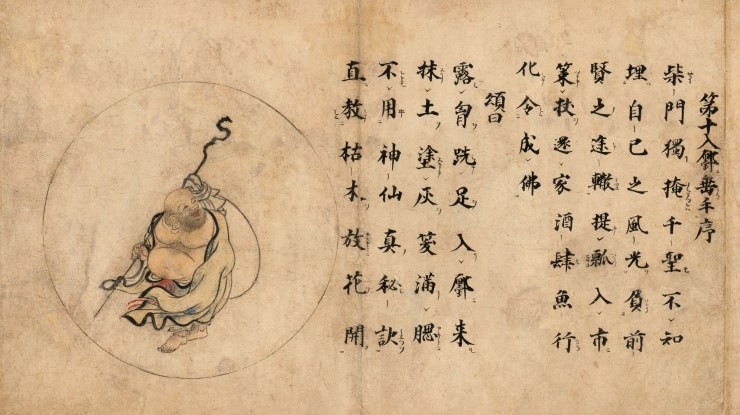

The Ten

Oxherding Songs

Handscroll, ink and color

on paper, Kamakura periond, 1278, (31 × 624.6 cm),

Collection of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, New York, NY

Translated by Gen P. Sakamoto

[With some

transliterated Chinese names corrected.]

十三世紀 禅宗 長卷 1278 年 紙本彩繪

尺寸: 31.1 x 624.8 cm

美國大都會藝術博物館收藏 隆日編譯

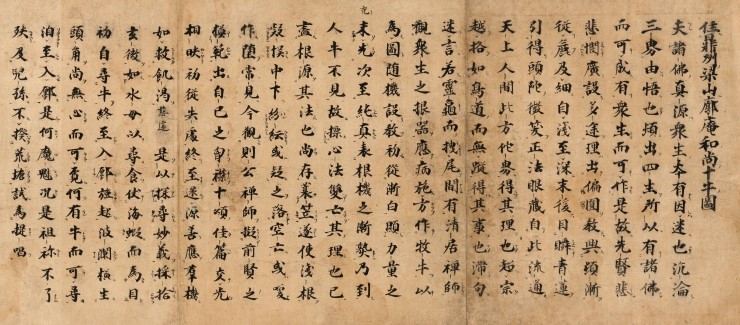

禪宗 用圖畫、文字將開悟的過程和在各個階段的體驗表現出來,系統地描繪出由修行而開悟而入世的心路歷程,這就是著名的牧牛圖及其圖頌。從詩學淵源上看,寒山禪 詩、汾陽頌古是其濫觴。〔參《禪宗詩歌境界》之《臨濟宗禪詩》章。〕 《十牛圖》用十幅圖畫描繪牧牛的過程,有圖、頌 ( 詩 ) 、文 ( 著語 ) ,表示了從尋牛覓心到歸家穩坐的過程,以闡示修行的方法與順序。〔《十牛圖頌》一卷,全稱《住鼎州梁山廓庵和尚十牛圖頌並序》,收于 續藏第一一三冊。〕 《十牛圖》與《信心銘》、《證道歌》、《坐禪儀》合印,稱四部錄,在禪林影響尤大。十牛圖用牧人和牛的形象,象徵修行者馴服心牛,以重現本‘來面目。

Preface, by the Monk Ciyuan

[On] the Ten Oxherding Pictures

by the Monk Kuoan [廓庵] of Mt. Liang, Dingzhou

In any case, all buddhas are the ultimate origin of things, and all sentient beings have Budhhahood within themselves. When one is deluded, one can sink into the three realms of illusion, but one can also be awakened and avoid being reborn into one of the four forms of life. Thus, there are those who could be enlightened and become buddhas, and those who are deluded.

For this very reason, the ancient sage [Buddha Shakyamuni] was compassionate enough to prepare a variety of paths [to enlightenment]. There is the priciple of the whole and its parts, enlightenment can be sudden or gradual, and the explanation can be from general to meticulous and from shallow to deep.

At the end of his life, when Shaka [Shakyamuni] blinked his green lotuslike eyes, his first disciple [Mahakasyapa] smiled and nodded. This was how the words for the true teaching were spread. Whether heavenly beings or human beings, in this world or in any other realm, those who attain [understanding of] the principle will transcend lineage or status, just as the flight path of a bird leaves no footprints. But one who is concerned only with facts becomes stagnant with phrases and at a loss for words, as if the divine tortoise had gotten stuck in the mud.

Recently, Chan [Zen] Master Qingju [清居], observing the potentials of people, created the parable of oxherding in order to treat their maladies; he drew it and taught it according to varying circumstances. It begins with the color of the ox gradually changing from black to white, indicating the change from non-achievement of one’s full potential to the final fulfillment of that potential – which is shown to be the ultimate source [enlightenment]. Both the ox and the oxherder finally become invisible, signifying the disappearance of both mind and doctrine. The principle is quite correct, but the teaching method still retains the metaphor of travel [progression]. As a result, it puzzles those with limited abilities, and confuses those who are mediocre. Some fear losing their sense of the [physical] world, while others scream an fall back upon their preconceived ideas.

From my point of view, the ten poems by Chan master Zegong [廓庵則公 Kuoan Zegong] were based on the works of his predecessors [like Qingju], but they were created from Zegong’s own heart, each poem sparkling like a jewel, and all reflecting one another. From the beginning when one is lost, to the end when one has returned to the ultimate source, all [of the poems] correspond very well to the different needs of people, like giving food to the hungry and water to the thirsty.

Therefore I, Ciyuan, will look for the essence and write a summary of each poem, just like a jellyfish searching for food by relying upon the eyes of a shrimp.

Beginning with the search of the ox and ending with the entry into the city may make unnecessary waves and cause the horns of the ox to protrude. If there is no mind to seek, where is the need to search for the ox? And to conclude the search by entering the city – is this the work of evil spirits? Perhaps not having obtained the approval of the ancestors will bring misfortune to coming generations, but while trying not to be absurd, I am going to comment on the [following] verses.

The Ten Oxherding Songs

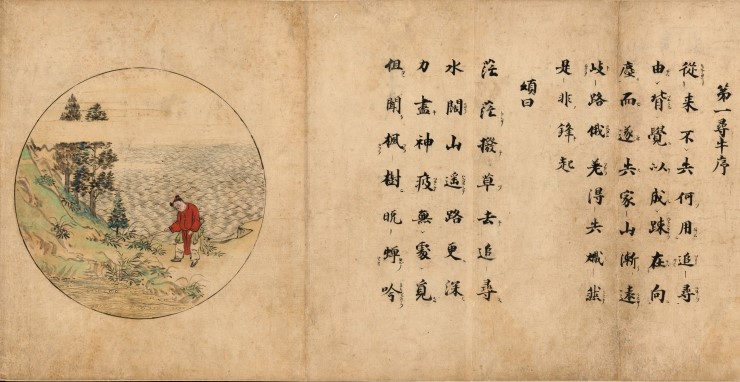

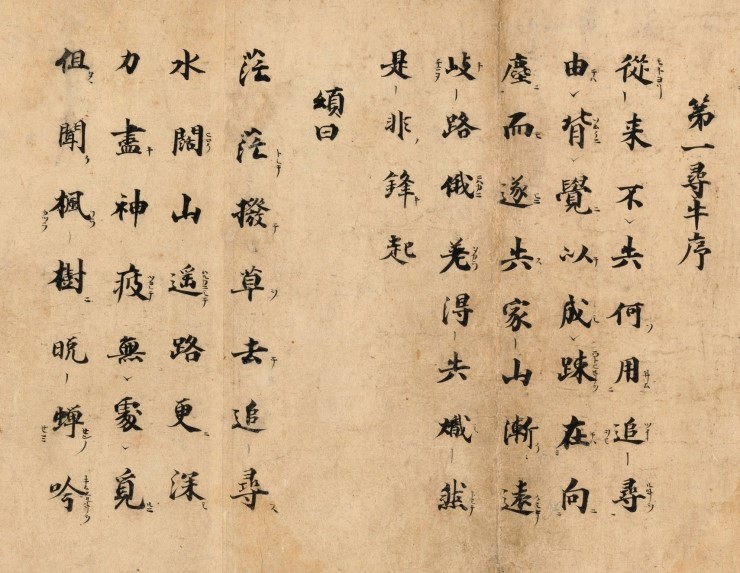

《尋牛》其一:

茫茫撥草去追尋,水闊山長路更深。

力盡神疲無覓處,但聞楓樹晚蟬吟。

“尋牛”,喻迷失自性。著語:“從來不 失,何用追尋?由背覺以成疏,在向塵而遂失。家山漸遠,歧路俄差。得失熾然,是非蜂起。”本心人人具足,由於相對觀念的生起,逐物迷己,人們貪逐外塵,悖 離本覺,心牛遂迷亂失落,離精神家園越來越遠。撥草尋牛,就是要尋回失落的清明本心。心牛迷失既遠,尋覓起來也很艱難,以至力盡神疲,也莫睹其蹤。然而於 山窮水盡處,驀現柳暗花明。在楓葉流丹晚蟬長吟中,隱隱有牛的蹤跡。

1. Searching for the Ox

COMMENTARY

Nothing has been lost in the first

place,

So what is the use of searching?

By refusing to come to one’s

senses,

One becomes separeted from

And eventually loses sight of what one seeks.

Home grows more and more distant,

And one comes to many crossroads.

Thoughts of gain and loss burn like

fire.

And ideas of right and wrong

Rise up like blade of a sword.

POEM

One aimlessly pushes the grasses

aside in search.

The rivers are wide, the mountains far away,

And the path becomes longer.

Exhausted and dispirited,

One hears only the late autumn

cicadas

Shrilling in the maple woods.

⌘

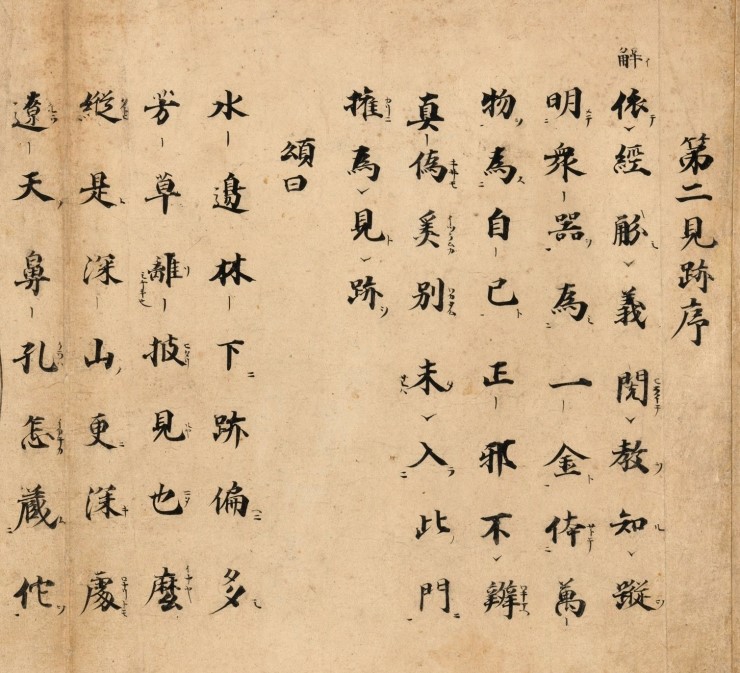

《見跡》其二:

水邊林下見遍多,芳草離披見也麼?

縱是深山更深處,遼天鼻孔怎藏他?

“見跡”,喻漸見心牛之跡。著語:“依經 解義,閱教知蹤。明眾金為一器,體萬物為自己。正邪不辨,真偽奚分?未入斯門,權為見跡。”修行者依據經典、禪書,探求修行意義,聆聽師家提撕,明天地同 根,萬物一體,甄別正邪真偽,領悟到禪的要義和方法,尋到了牛的足跡。深山更深處也掩藏不住鼻孔朝天的牛,無明荒草再深也遮蔽不了清明本心。但見跡還沒有 見牛,還沒有進入禪門。

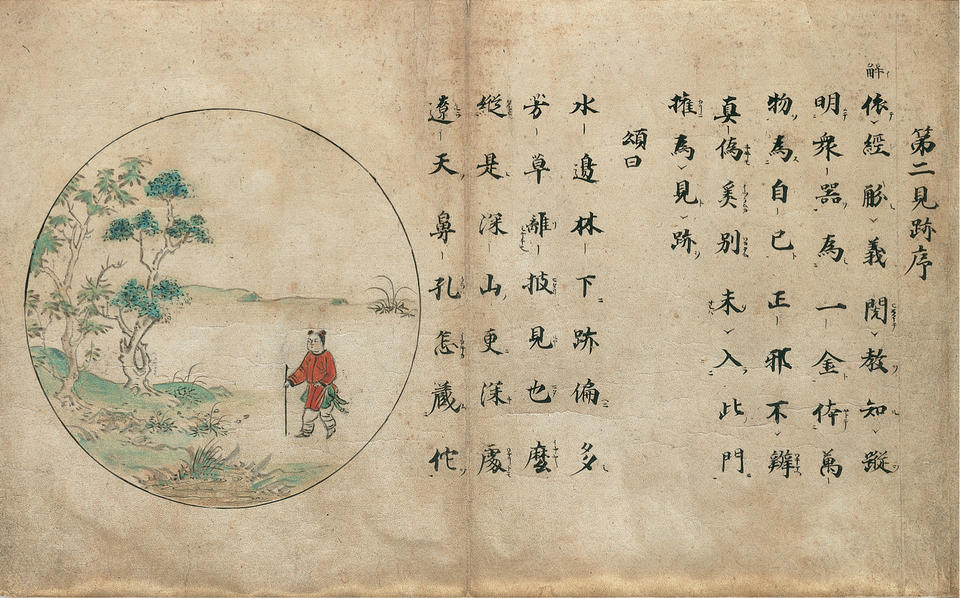

2. Seeing the Footprints of the Ox

COMMENTARY

Relying on sutras, one comprehends

the meaning,

And studying the doctrines, one finds some traces.

As it becomes clear that differently

shaped metal vessels

Are all made from the same piece of metal,

One realizes that the myriad entities [one thinks one sees]

Are formulated by oneself.

Unless one can separate the orthodox

from the heretics,

How can one distinguish the true from the untrue?

Not having entered the gate as yet,

At least one has noticed the traces.

POEM

By the water, and under the trees,

There are numerous traces.

Fragrant grasses grow thickly,

Did you see the ox?

Even in the depths of the distant mountain forest,

How could the upturned nostrils of the ox be concealed?

⌘

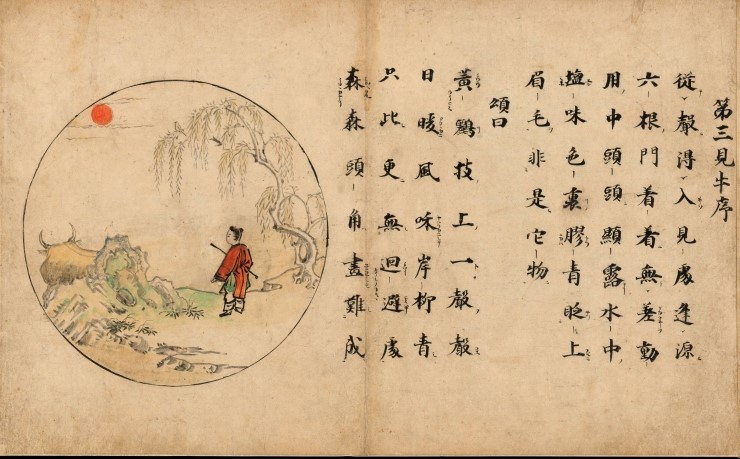

《見牛》其三:

黃鶯枝上一聲聲,日暖風和柳岸青。

只此更無回避處,森森頭角畫難成。

“見牛”,喻發現本具之心牛。著語:“從 聲入得,見處逢源。六根門著著無差,動用中頭頭顯露。水中鹽味,色裏膠青。眨上眉毛,非是他物。”黃鶯清啼,日暖風和,柳枝搖綠,賞心悅目。“本來面目” 通過聲色等呈顯出來,處處都有它的作用,但它又是如此的妙用無痕,如水中鹽味,色裏膠青,必須具備慧耳慧目,才能使它無處回避。它頭角森森,卻又離形絕 相,絕非丹青所能描畫。見牛較之見跡是一大進步,但見牛並非得牛,見道尚非得道,它只是初步開悟。

3. Seeing the Ox

COMMENTARY

Led by the sound, one starts out on

the path

And at first sight of it, one sees the origin of things.

All of one’s senses work

hamoniously,

Their presence manifest in all the things one usually does.

Just like the taste of salt in water,

or the glue in dye,

[It is definitely there, but is not discreet.]

If one’s eyes are widw open,

One sees it [truth] clearly, not as something else.

POEM

A bush warbler sings upon a branch,

Warm sun, soft breezes, green willows on the bank.

Nowhere can the ox escape to hide,

But those majestic horns are difficult to draw.

⌘

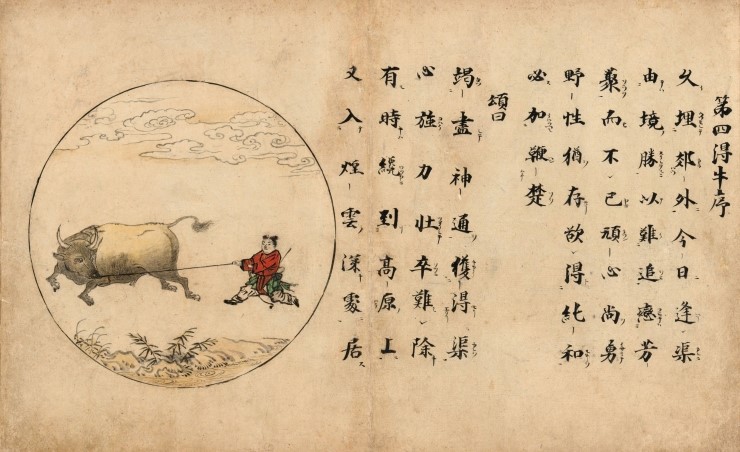

《得牛》其四:

竭盡精神獲得渠,心強力壯卒難除。

有時才到高原上,又入煙霞深處居。

“得牛”,喻已證悟自性。著語:“久埋郊 外,今日逢渠。由境勝以難追,戀芳叢而不已。頑心尚勇,野性猶存。欲得純和,必加鞭撻。”雖然得到了牛,但這是一隻長期賓士在妄想原野的心牛,野性猶頑, 惡習難以頓除。它時而奔突在高山曠野,時而貪戀于芳草園林,因此仍需緊把鼻繩,用嚴厲的手段,來馴化它的習性。修道者雖然見道,但無始以來的習性猶深,受 到外界影響時,極易退墮到未開悟以前的情境,必須嚴苛自律,羈鎖住慣於分別、取捨的意識。對此,禪宗謂之“見惑 ( 理知的惑 ) 可頓斷如破石,思惑 ( 情意的惑 ) 需漸斷如藕絲”。見性 ( 悟 ) 固然不易,悟後的修行更重要。因此得牛之後,還須繼續牧牛。

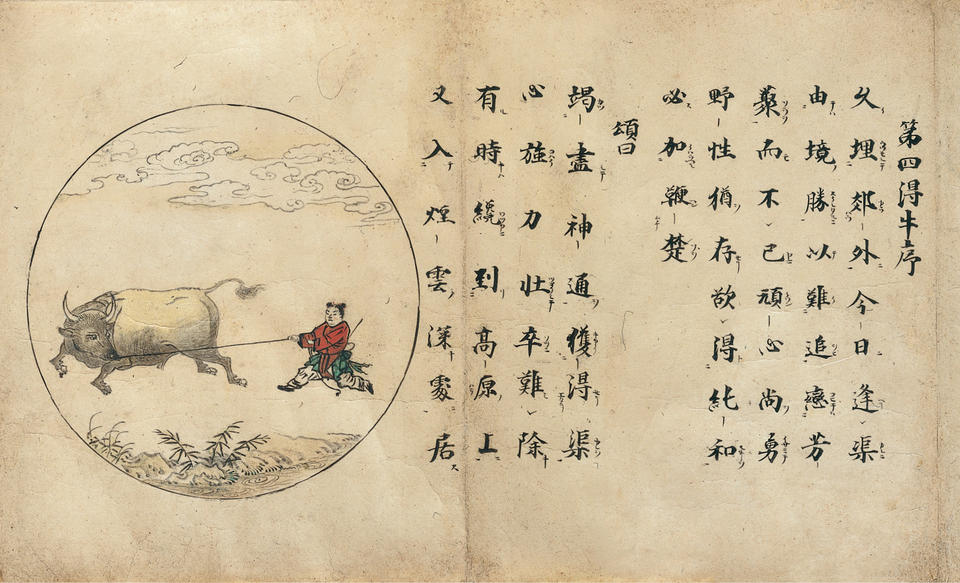

4. Catching the Ox

COMMENTARY

The ox lived in obscurity in the

field for so long,

But I found him today.

While I am distracted by the

beautiful scenery,

And the difficult chase,

The ox is longing for fragrant grass.

His mind is still stubborn,

And his wild nature yet remains.

If I wish him tamed, I must whip him.

POEM

With all my energy, I seize the ox.

His will is strong, and his power

inexhaustible,

He cannot be tamed easily.

Sometimes he charges to the high plateau.

And there he stays, deep in the mist.

⌘

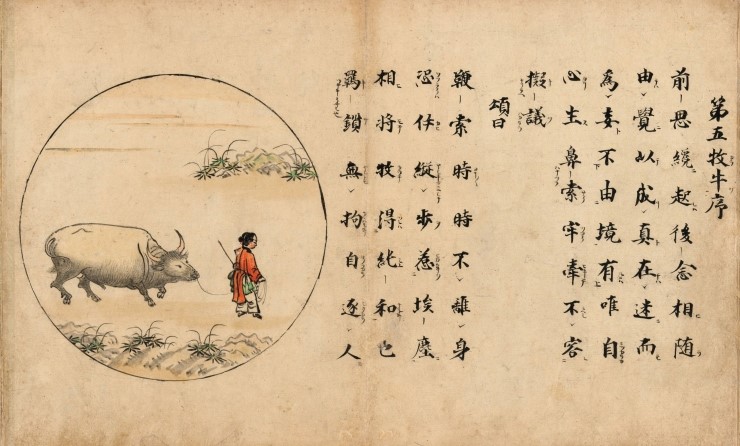

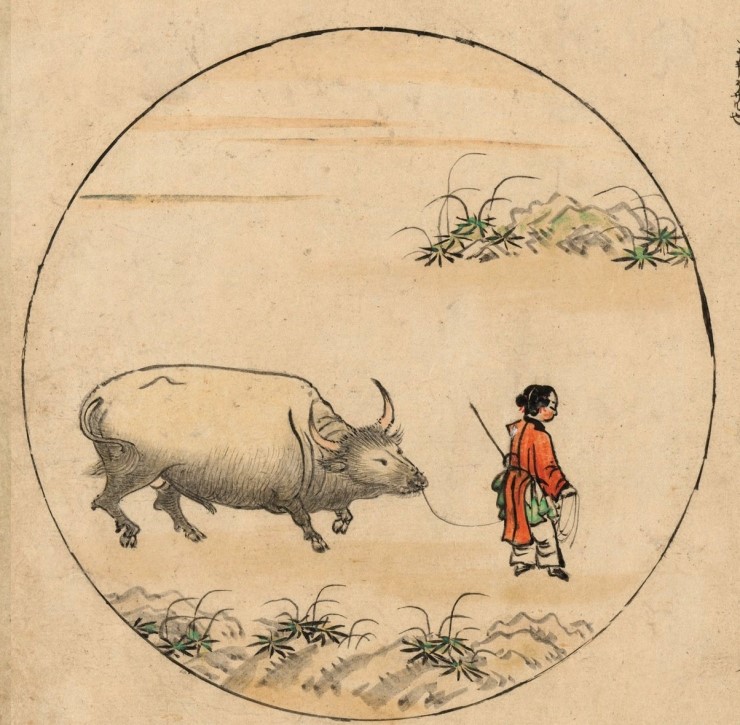

《牧牛》其五:

鞭索時時不離身,恐伊縱步入埃塵。

相將牧得純和也,羈鎖無拘自逐人。

“牧牛”,喻悟後調心。著語:“前思才起,後念相隨。由覺故以成真,在迷故而為妄。不由境有,惟有心生。鼻索牢牽,不容擬議。”人的思想之流如長江大河,念念不停流。雖然見牛,並不意味著一了百了,隨時都有無明發生,“毫釐繫念,三途業因。瞥爾情生,萬劫羈鎖” ( 《五燈》卷七《宣鑒》 ) 。 因此開悟之後要繼續保任,要不斷地斷 除煩惱,攝伏妄念。前一階段是奪人,這一階段是奪境。人們在日常的差別境中,一念剛起,二念隨生。迷惑的起因在於二念,若在一念興起時,能如紅爐點雪,頓 作消熔,就不會生起迷執。對此禪宗稱之為“後念不生,前念自滅”。時時用菩提正見觀照,直臻於純和之境,才是覺悟證真,不為境遷。此時種種調伏手段即可棄 而不用,人牛相得。

5. Herding the Ox

COMMENTARY

As one becomes conscious, more thoughts follow.

Awakening to one’s senses, the

truth is achieved,

But in losing one’s senses, delusion prevails.

Delusion is not caused by the object

But is only created by the subject.

[Delusions originate in us, not in the world around us.]

Pull tightly on the nose-rope

And do not hesitate.

POEM

One does not let go of the whip or

the rope,

Afraid it will stray and choose the dusty mist.

A well-tended ox becomes gentle,

And even with no rope will follow people by himself.

⌘

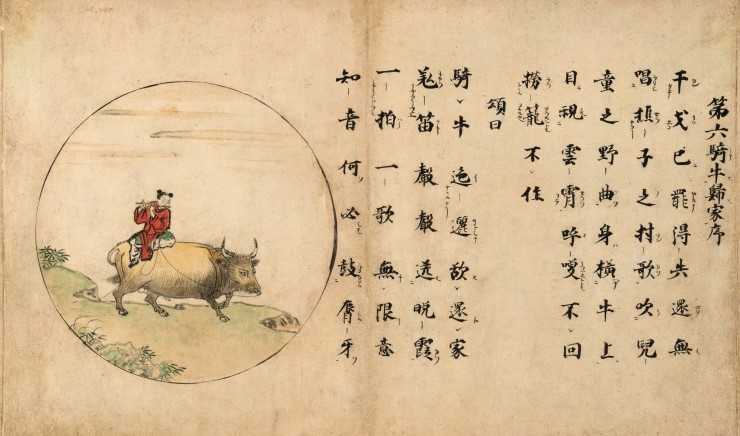

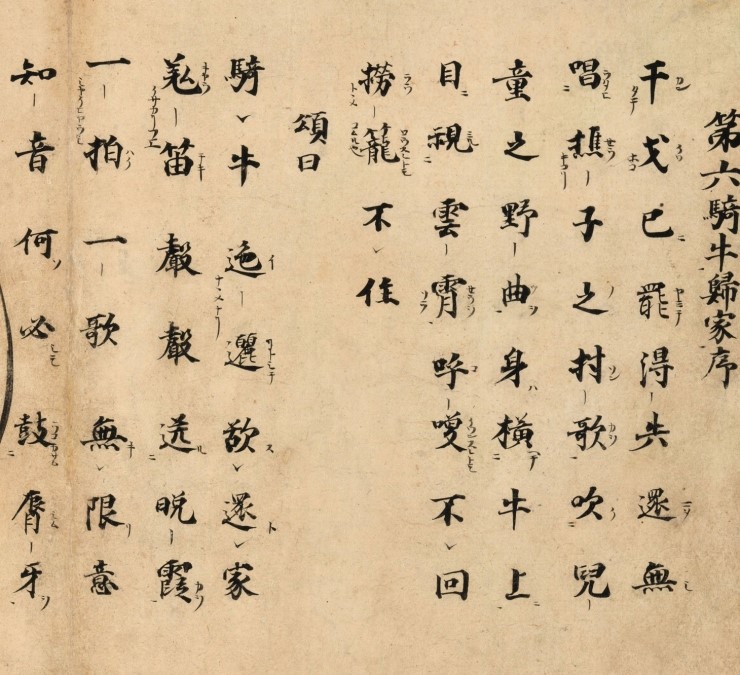

《騎牛歸家》其六:

騎牛迤邐欲還家,羌笛聲聲送晚霞。

一拍一歌無限意,知音何必鼓唇牙!

“騎牛歸家”,喻騎乘馴服的心牛歸於精神的故里。著語:“干戈已罷,得失還無。唱樵子之村歌,吹兒童之野曲。橫身牛上,目視雲霄。呼喚不回,牢籠不住。”學禪者經過了發心 ( 尋牛 ) 、學習佛禪義理 ( 見跡 ) 、修行而見性 ( 見牛 ) 、見性悟道 ( 得牛 ) 、在正念相續中精益求精 ( 牧牛 ) ,可謂艱難曲折備曆辛苦。馴牛之時,尚需要不斷地鞭撻。修行者進行 艱苦的砥礪,終於使心靈脫離情識妄想的羈絆。心牛馴服,人牛合一,已臻一體之境。此時,妄想已被調伏,本心無染,清明澄澈,充滿喜悅。一如天真爛漫的牧 童,笛橫牛背,沐浴晚霞,騎牛歸家。一拍一歌,於不經意間,都有無限天真妙趣,知音者自當會心一笑。

6. Riding the Ox and Returning Home

COMMENTARY

The struggle is over,

No more gain or loss.

Sing the village woodcutter’s

song,

And play on the flute the tunes of children,

Sitting sideways on top of the ox,

eyes fixed on the clouds in the sky,

If called, not turning back,

Or if stopped, not ever staying.

POEM

Riding the bull, I leisurely wander

toward home,

Exotic flute melodies echo through sunset clouds,

Each beat and each tune indescribably profound,

No words are needed for those who understand music.

⌘

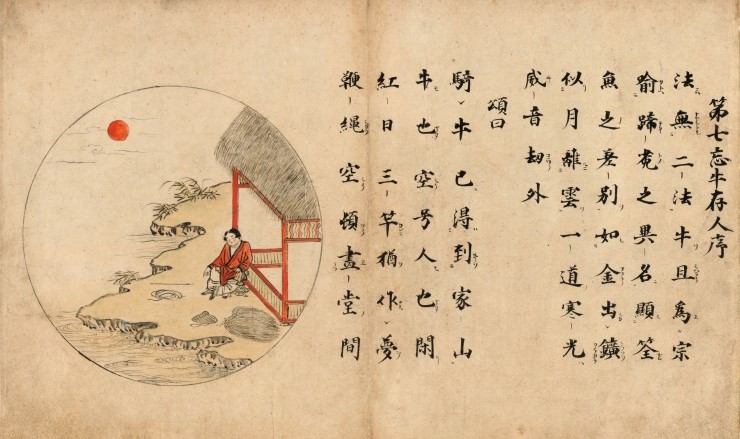

《忘牛存人》其七:

騎牛已得到家山,牛也空兮人也閑。

紅日三竿猶作夢,鞭繩空頓草堂間。

“忘牛存人”,喻既已回到本覺無為的精神 故鄉,不須再修,無事安閒。著語:“法無二法,牛且為宗。喻蹄兔之異名,顯筌魚之差別。如金出礦,似月離雲。一道寒光,威音劫外。”騎牛回家,牛已回到本 處。牧童既已得牛,尋牛之心已忘,便可高枕而臥。此時無煩惱可斷,無妄心可調,“憎愛不關心,長伸兩腳臥” ( 《壇經•般若品》 ) 。 沒有內境外境的分別,也沒有煩惱和菩提的執著。但牛雖忘,人猶存,“我”還沒有空掉。

7. The Ox Forgotten, the Man Remains

COMMENTARY

There is only one law, and the ox is hypothetical.

The rabbit snare is not the rabbit,

nor the fishnet the fish.

[Once the rabbit or fish is caught, the trap or net is no longer needed.]

Like gold separated from dross,

Or the moon emerging from cloud,

The ray of light has been shining

Since before the beginning of time.

POEM

Riding on the ox, he has come home.

There is no ox there, and he is at ease.

Although the sun is high, he is still dreamy.

The whip and rope abandoned in the thatched hut.

⌘

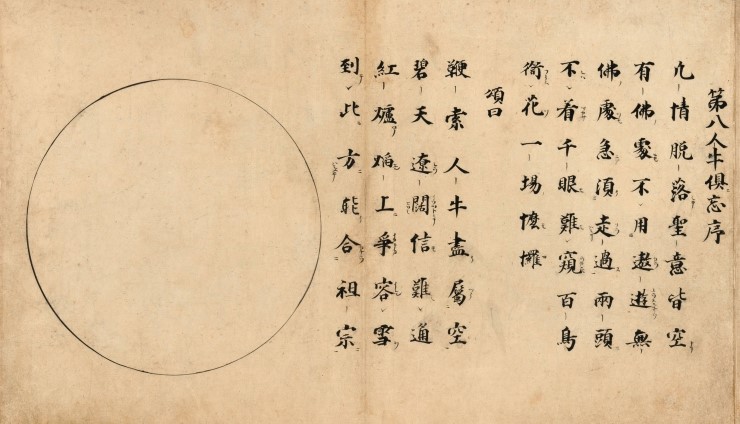

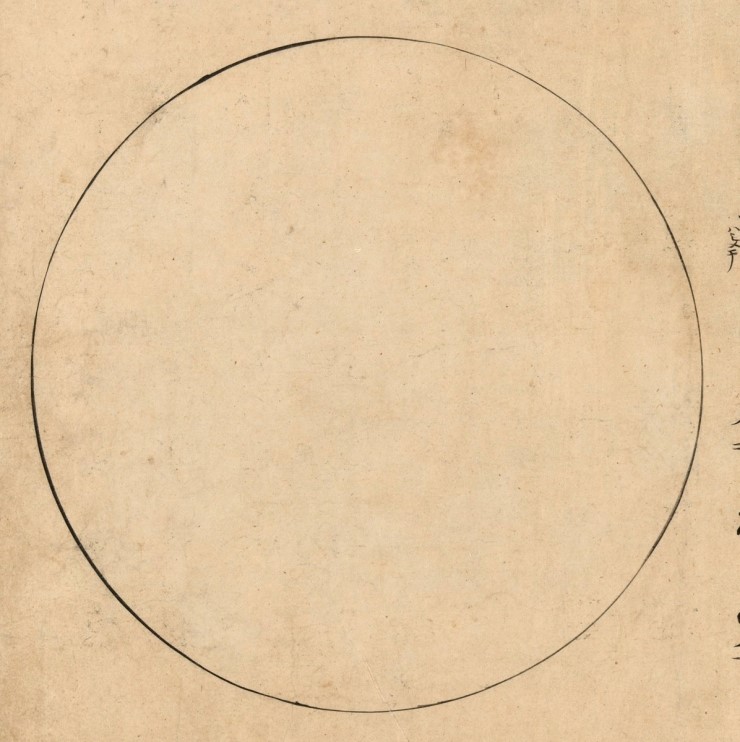

《人牛俱忘》其八:

鞭索人牛盡屬空,碧天遼闊信難通。

紅爐焰上爭容雪,到此方能合祖宗。

“人牛俱忘”,喻凡情脫落而全界無物,凡聖共泯,生佛俱空。不僅迷惑的心脫落了,甚至連覺悟的心也沒有了。著語:“凡情脫落,聖意皆空。有佛處不用遨遊,無佛處急須走過。兩頭不著,佛眼難窺。百鳥銜花,一場 忄麼 忄羅 。”凡情脫落,是修道初階;聖意皆空,是了悟而沒有了悟之心的無所得智。有佛處不遨遊,不住悟境;無佛處急走過,不落見取。超越凡聖,截斷兩頭,遠遠勝過牛頭耽溺聖境而導致的百鳥銜花。牛頭由 於四祖的教化而使佛見、法見悉皆消泯,百鳥遂無從窺其境界。此時內無我,外無法,能所俱泯,主客皆空。自性之光,猶如紅爐烈焰,舉凡善惡、美醜、是非、生死、得失等相對觀念,一一如同片雪投爐,銷熔於絕對,此時才是祖師禪的境界。

8. The Ox and the Man, Both Forgotten

COMMENTARY

All confusion fallen away,

The enlightened mind is not there.

No need to linger in the realm of

Buddha;

But always pass quickly

Through the realm of no Buddha.

Not lingering in either realm, one cannot be seen.

Hundreds of birds bringing flowers

Are an embarrassment.

[Praise is meaningless.]

POEM

Whip, rope, man, and ox,

all are non-existent.

The blue sky being vast,

No message can be heard,

Just as the snowflake cannot last

In the flaming red furnace.

After this state,

One can join the ancient teachers.

⌘

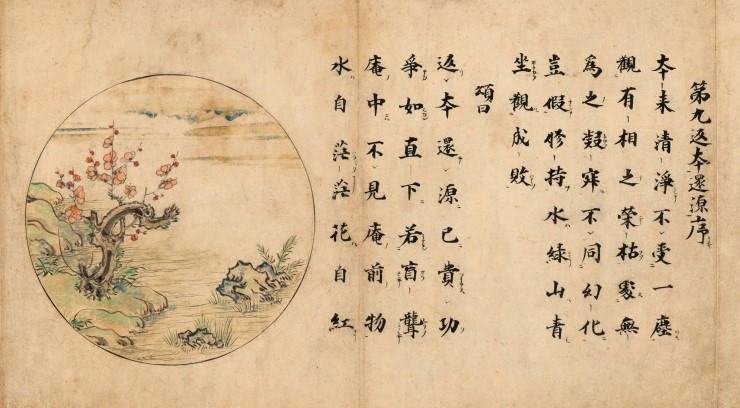

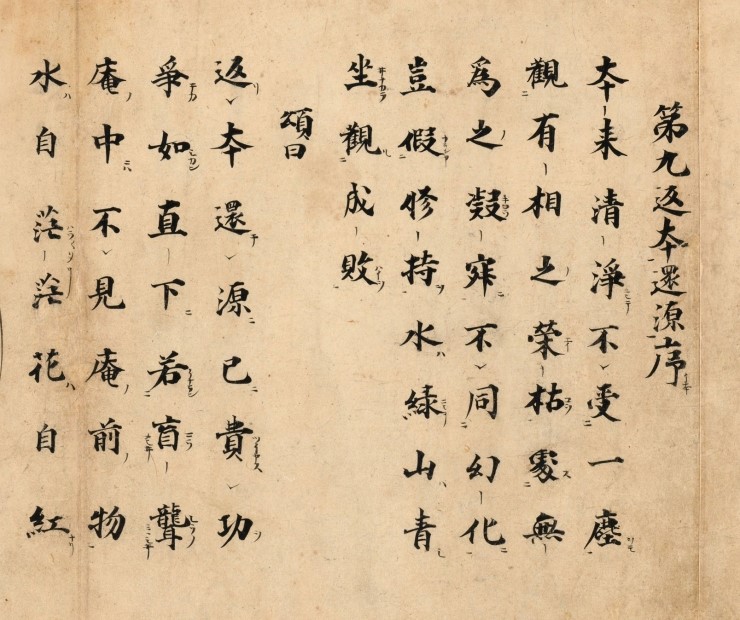

《返本還源》其九:

返本還源已費功,爭如直下若盲聾。

庵中不見庵前物,水自茫茫花自紅。

“返本還源”,喻本心清淨,無煩惱妄念, 當體即諸法實相。著語:“本來清淨,不受一塵。觀有相之榮枯,處無為之凝寂。不同幻化,豈假修冶?水綠山青,坐觀成敗。”本心清淨澄明,猶如山青水綠。此 時我非我,見非見,山只是山,水只是水。尋牛、見跡、見牛、得牛、牧牛、騎牛歸家,直至忘牛存人、人牛俱忘,都是返本還源的過程,這個過程“費功”尤多。 但既已返本還源,渡河須忘筏,到岸不須船,對所費的一切功夫,就應當放下,不可再粘著。要直截根源,關閉眼耳等感官之門,因為“從門入者,不是家珍。認影 迷頭,豈非大錯” ( 《傳燈》卷十六《月輪》 ) 。 此時迴光返照,如聾似啞。視而不見,聽而不聞。主體置身萬象之中,而又超然物外,水月相忘,孤明歷歷。在本來清淨的真如實相中,靜觀萬物的榮枯流轉,而不為外境所動,不隨波逐流。

9. Return to the Fundamentals, Back to the Source

COMMENTARY

Pure and clear from the beginning, free of any dust.

From the realm of non-being,

One observes the rising and falling [transitory changes]

In the world of forms.

It is not the same as magic, so why need one embellish?

The water is blue, the mountain

green.

Calmly seated, one observes the ups and downs of the world.

POEM

In returning to the fundamentals and

going back to the source,

I had to work so hard.

Perhaps it would be better to be blind and deaf.

Being in the hut, I do not see what is outside.

The river flowing tranquilly,

The flower simply being red.

⌘

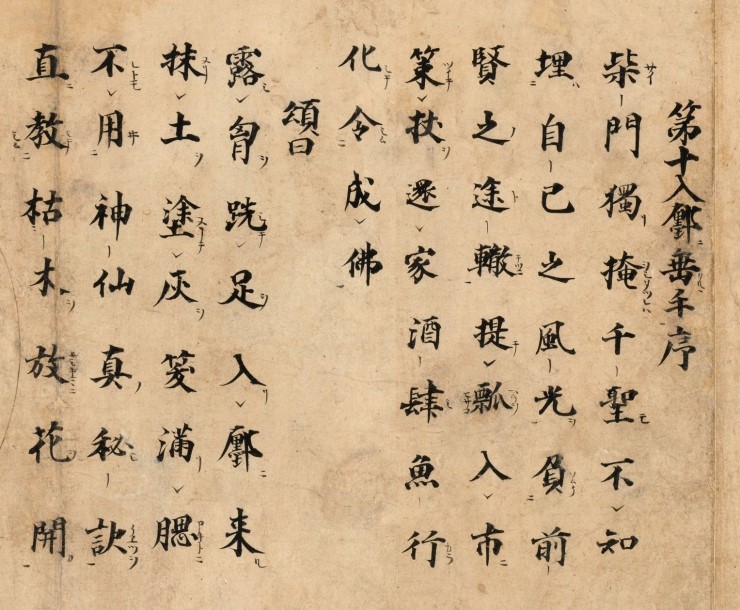

《入廛垂手》其十:

露胸跣足入廛來,抹土塗灰笑滿腮。

不用神仙真秘訣,直教枯木放花開。

“入廛垂手”,喻不居正位,入利他之境。 著語:“柴門獨掩,千聖不知。埋自己之風光,負前聖之途轍。提瓢入市,策杖還家。酒肆魚行,化令成佛!”開悟之後,不可高居聖境,只滿足于個人成佛,而要 百尺竿頭,更進一步,從正位轉身而出,回到現實社會中來。“露足跣胸”,象徵佛性禪心,一塵不染,淨裸裸,赤灑灑。禪者灰頭土面地化導眾生,將自己所證悟 的真理與眾人分享,喜悅祥和,毫不倦怠。這就是大乘菩薩的下座行,是灰頭土面的利他行。

10. Entering the City with Hands Hanging Down

COMMENTARY

The brushwood gate of the hut is

closed,

Even thousands of sages could not know what is within.

I conceal the beauty of where I am,

And refuse to follow the path

Of the wise men of the past.

Holding my wine gourd, I enter the

market;

Using my stick I return home.

Wine shop and fish market

Become Buddha

And enlighten me.

POEM

He enters the city barefoot, with

chest exposed.

Covered in dust and ashes, smiling broadly.

No need for the magic powers of the gods and immortals,

Just let the dead tree bloom again.

⌘

牧 牛圖頌不僅流行國內,引起了無數後世禪人的吟和,而且遠播韓國、日本,產生了非常廣泛的影響。日本的一山國師著有《十牛圖頌》,即是依廓庵《十牛圖頌》的 框架創作而成。一山在序中說:“十牛圖,古宿無途轍中途轍也。若論此事,眨上眉毛,早已蹉過,況有淺深次第之異乎?然去聖愈遠,法當危末,根性多優劣,機 用有遲速,又不可一概定之,故未免曲設多方,以誘掖之,此圖之作是耶!”由此可見,《牧牛圖頌》把修心過程分成十個階段的作法,只是為了接引初機者所設立 的方便而已。從頓悟的立場上看,牧牛的十個階段可以濃縮在刹那完成,毫無朕跡可尋。從方便門看,《十牛圖頌》將神秘的禪悟直覺體驗,分解為逐漸演化的階 次,為初學者指出了一條切實可行的用功方向。

《十牛圖頌》用象徵的手法寫調心開悟,沒有抽象的理論,純是一幅幅鮮明可感的藝術形象,通過意象的組合、變換,將調心、開悟的過程寫得生動凝 練,寓意奇深。在禪宗史上,形成了牧牛文學,為禪宗哲學,增添了瑰美的景觀。

⌘ ⌘ ⌘

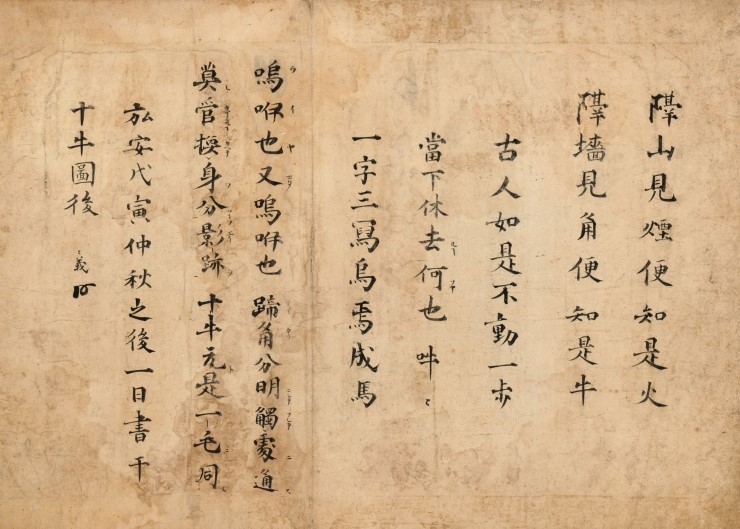

The Ten Ox-Herding Songs ( 十牛図巻 ) by the Monk Kakuan (Ch. Guoan, 廓庵; fl. ca. 1150) of Teishū Ryōzan (Ch. Dingzhou Liangshan, 鼎州梁山)

http://burkecollection.org/catalogue/31-the-ten-ox-herding-songs-by-the-monk-kakuan-ch-guoan-fl-ca-of-teish%C5%AB-ry%C5%8Dzan-ch-dingzhou-liangshan

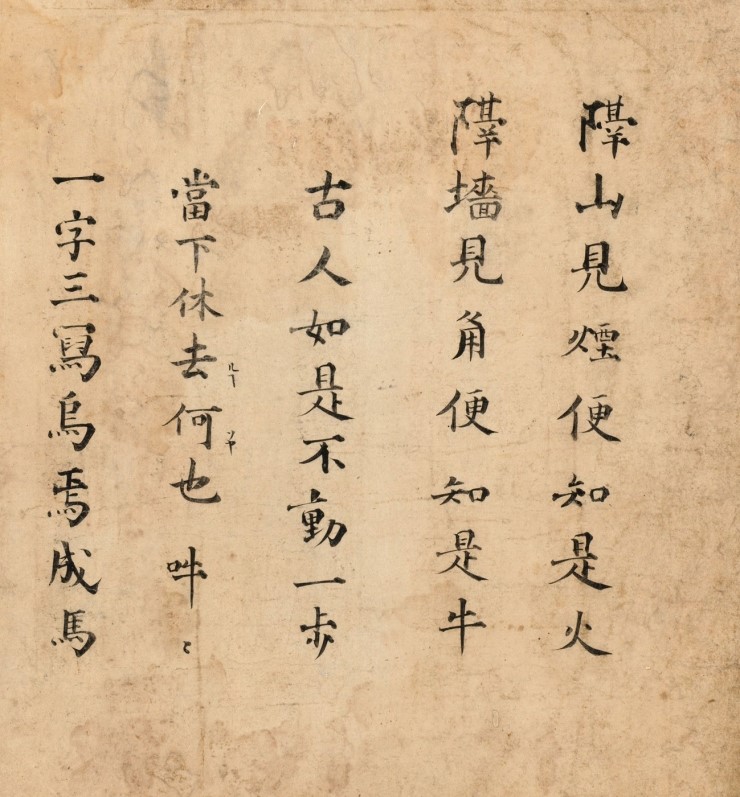

Song 2. Seeing the Footprints of the Ox

Commentary / Relying on sutras, one comprehends the meaning, / and studying the doctrines, one finds some traces. / As it becomes clear that differently shaped metal vessels / are all made from the same piece of metal, / one realizes that the myriad entities [one thinks one sees] / are formulated by oneself. / Unless one can separate the orthodox from the heretics, / how can one distinguish the true from the untrue? / Not having entered the gate as yet, / at least one has noticed the traces.

Poem / By the water, and under the trees, / there are numerous traces. / Fragrant grasses grow thickly, / did you see the ox? / Even in the depths of the distant mountain forest, / how could the upturned nostrils of the ox be concealed?

Song 4. Catching the Ox

Commentary / The ox lived in obscurity in the field for so long, / but I found him today. // While I am distracted by the beautiful scenery, / and the difficult chase, / the ox is longing for fragrant grass. // His mind is still stubborn. / And his wild nature yet remains. // If I wish him tamed, I must whip him.

Poem / With all my energy, I seize the ox. // His will is strong, and his power inexhaustible. / He cannot be tamed easily. // Sometimes he charges to the high plateau, // and there he stays, deep in the mist.

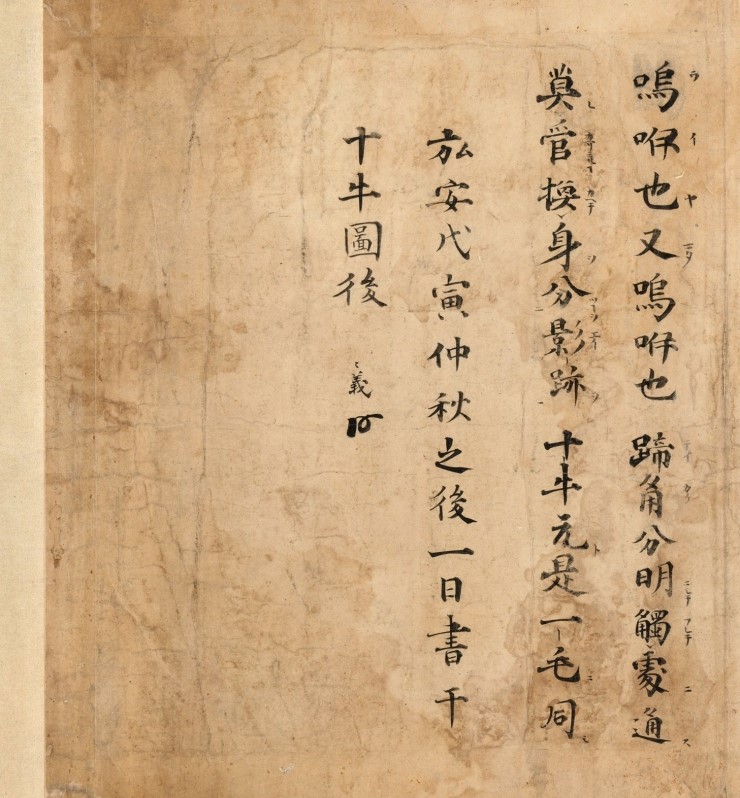

Signature

In the Year of the Fifth Tiger of the Kōan Era [1278] , on the sixteenth day of the eighth month, I am inscribing the postscript of the Ten Pictures of the Ox ; [illegible] gi

Seal

[at end of scroll] kaō