ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen index

« Home

The Ten Oxherding Pictures

by 普明

Puming [Fumyō], an unknown author

Nichiren Buddhist Commentary by Ryuei Michael McCormick (USA, 2011)

Woodblock prints from the Jiaxing Tripitaka (嘉興藏)

Vol. 23, No. B.128, p. 347ff.

http://fraughtwithperil.com/ryuei/2011/07/09/the-ten-ox-herding-pictures-with-accompanying-verses/

Below is my translation and commentary on the verses accompanying the

Ten Oxherding Pictures that the founder of Won Buddhism, Pak

Chung-bin (1891-1943; aka the Great Master Sot’aesan) selected

for his disciples to study. He himself specifically spoke of spiritual training

in his own order by using the metaphor of oxherding in two discourses. Those

two discourses are numbers 54 and

The Ten Oxherding Pictures are a pictorial analogy of the development of spiritual practice in terms of a young boy looking for a lost ox, taming it, and then bringing it home. The analogy of oxherding can be found in the discourses of Shakyamuni Buddha, and in the Sung dynasty the Ch’an (J. Zen) school began to produce these pictures with accompanying verses to illustrate the analogy and invest it with their own ideas about spiritual practice. According to D.T. Suzuki in his Manual of Zen the first Ch’an master to do this was named Ching-chu (n.d.). Ching-chu produced a set of five pictures in which a black ox gradually whitens and then disappears entirely in the fifth and last picture. Another master named Kuo-an Shih-yuan (n.d.) of the Lin-chi school of Zen referred to this earlier set in a preface to his own set of pictures and verses. In Kuo-an’s version the ox does not change color and there are ten pictures in which the empty circle is only the eighth picture and is followed by a scene of nature with no people in it and then a picture of a bodhisattva (usually portrayed as the 10th century monk Pu-tai, the so called “Happy Buddha”) entering the market place. Kuo-an’s concern was that the Ch’an or Zen path not end in what might appear to be a mere negation. There was another series of pictures and verses by a Ch’an master named Tzu-te Hui who followed the model of Ching-chu with the addition of a sixth picture with verses wherein the awakened one returns to everyday life to help all beings. In 1585 another set of pictures was published by a man named Chu-hung (n.d.) with verses by someone named Pu-ming (n.d.). In the Chu-hung/Pu-ming version there are ten pictures in which the ox gradually whitens and then disappears in the tenth picture. All of this is according to D.T. Suzuki on pp. 127-129 of the Grove Press edition of his Manual of Zen Buddhism. Now for reasons that I do not know, it was the verses of Pu-ming that Sot’aesan selected. If it has been up to me, I would have chosen the version by Kuo-an that goes beyond the empty circle and explicitly points out that the awakened one returns to the world “with bliss-bestowing hands.”

Before looking at the pictures and Pu-ming’s verses I would like

to briefly survey a few key sutra passages and teachings of Sot’aesan

that I think will help explain what they are about. In the Pali Canon there are

three discourses that I know of that specifically use the simile of oxherding

(or cowherding according to the translation by Bhikkhu Nanamoli and Bhikkhu

Bodhi). These three discourses are the Two

Kings of Thought (P. Dvedhavitakka

Sutta), The Greater Discourse on

the Cowherd (P. Mahagopalaka

Sutta), and The Shorter

Discourse on the Cowherd (P. Culagopalaka

Sutta). These are respectively discourses 19, 33, and

Just as in the last month of the rainy season, in the autumn, when the crops thicken, a cowherd would guard his cows by constantly tapping and poking them on this side and that with a stick to check and curb them. Why is that? Because he sees that he could be flogged, imprisoned, fined, or blamed [if he let them stray into the crops]. So too I saw in unwholesome states danger, degradation, and defilement, and in wholesome states the blessing of renunciation, the aspect of cleansing. (Nanamoli & Bodhi, p. 208)

He compares the bare awareness of wholesome thoughts and the cultivating of a concentrated, undisturbed mind to a cowherd after the crops have been gathered who only needs to quietly watch the cows without interfering with them.

Just as in the last month of the hot season, when all the crops have been brought inside the villages, a cowherd would guard his cows while staying at the root of a tree or out in the open, since he needs only to be mindful that the cows are there; so too there was need for me only to be mindful that those states were there. (Ibid, p. 209)

In the discourse, the cows are representative of thoughts, whether wholesome or unwholesome. Keeping control of the herd and being mindful of them is compared to controlling and being mindful of one’s thoughts, until one can then attain the states of concentration known as the dhyanas, in which negative thoughts are overcome. In the higher dhyanas, discursive thoughts drop away entirely. This clears the way for a direct perception of reality once the mind that is clear and one-pointed is utilized for insight practice, the observation of phenomena as they are.

There are short teachings in the Numerical Discourses of the Buddha (P. Anguttara Nikaya) that speak not of controlling thoughts but of the mind generally. In one teaching he says:

No other thing do I know, O monks, that brings so much harm as a mind that is untamed, unguarded, unprotected, and uncontrolled. Such a mind truly brings much harm.

No other thing do I know, O monks, that brings so much benefit as a mind that is tamed, guarded, protected, and controlled. Such a mind truly brings great benefit. (Nyanaponika & Bodhi, p. 35)

I think we can see that in terms of this teaching it would be easy to speak of a single cow or ox as representing the mind, the field of thoughts and awareness. But what is the true nature of mind? Is it just wild and uncontrolled until it has been domesticated? Surprisingly, another teaching from the Numerical Discourses points to a far more positive evaluation of the true nature of mind.

This mind, O monks, is luminous, but it is defiled by adventitious defilements. The uninstructed worldling does not understand this as it really is; therefore for him there is no mental development.

This mind, O monks, is luminous, and it is freed from adventitious defilement. The instructed noble disciple understands this as it really is; therefore for him there is mental development. (Ibid, p. 36)

This would suggest that the mind is inherently luminous, clear and pure; but that the defilements of greed, hatred, and delusion are clouding or obscuring this luminosity. Nevertheless, if one can gain some insight or assurance that the defilements or not inherent but that luminosity is the true nature of mind then one can become a noble disciple and develop the mind thereby freeing it of the adventitious defilements and attaining awakening. This kind of teaching is expanded upon in Mahayana sutras such as the Lankavatara Sutra. In the Lankavatara Sutra the mind is spoken of in two ways. From one perspective, it is the storehouse consciousness (S. alaya-vijnana), the deep subconscious storage place of defilements, memories, habit-patterns, and of the seeds of future effects planted by karmic activity. The storehouse consciousness is the source of all other forms of consciousness (i.e. the seven consciousnesses of seeing, hearing, tasting, smelling, touching, thoughts & feelings, and a sense of self or ego) and it is likened to a deep ocean upon which the other forms of consciousness rise and fall like waves. This first perspective views the mind as defiled by greed, hatred, delusion, and the impetus of past karma. Another perspective views the mind as the tathagatagarbha, which means “matrix of the tathagata.” “Tathagata” is another title used for a Buddha and so the “matrix of the tathagata” means that which will produce or is productive of a buddha. The term is really a synonym for buddha-nature. In other words, mind is buddha-nature, the obscured true nature that will be revealed and manifested if the defilements can be overturned in the depths of the mind through Buddhist practice. The following passage of the Lankavatara Sutra provides a sample of how the mind is equated with both tathagatagarbha and the storehouse consciousness:

The Blessed One said this to him: Mahamati, the tathagatagarbha holds within it the cause for both good and evil, and by it all the forms of existence are produced. Like an actor it takes on a variety of forms, and [in itself] id devoid of a self or what belongs to it. As this is not understood, there is the functioning together of the triple combination from which effects take place. But the philosophers not knowing this are tenaciously attached to the idea of a cause [or a creating agency]. Because of the influence of habit-energy that has been accumulating variously by false reasoning since beginningless time, what here goes under the name of storehouse consciousness is accompanied by the seven consciousnesses which give birth to a state known as the abode of ignorance. It is like a great ocean in which the waves roll on permanently but the [deeps remain unmoved; that is the storehouse-] body itself subsists uninterruptedly, quite free from fault of impermanence, unconcerned with the view of self-nature, and thoroughly pure in its essential nature. (Suzuki 1994, p. 191)

Now I will grant that the above passage is quite difficult to understand. So let me try to clarify some points. In Buddhism, all schools agree that there are at least the six consciousnesses of sight, hearing, tasting, smelling, and a sixth consciousness of mental phenomena such as thoughts and feelings that also serves to coordinate the data taken in by the five sensory consciousnesses. In the Mahayana teachings represented by sutras like the Lankavatara Sutra, two more consciousnesses were added to these first six. The seventh is the ego-consciousnesses which is responsible for maintaining a sense of ego or self-identity. The eighth is the storehouse consciousnesses. The ego-consciousnesses mistakenly takes hold of the sense of continuity provided by the storehouse consciousness to postulate an actual substantial independent self-nature. This is what the brahmins have mistakenly viewed as the atman or true self. It is this that is sometimes taken to be the primary cause for the actual production of the world and all the beings in it. Mahayana Buddhism does not, however, mean for the storehouse consciousness to be taken for any kind of self-nature or theistic creator of an an objective world. Rather, the storehouse consciousnesses is more of a field of dynamic interdependent activity that gives rise, due to the defilements, to the impressions of an objective world and a subjective experiencer and actor. When the storehouse consciousness is recognized for what it really is then the world is seen as not composed of subjects and objects but as a mentally produced interplay of causes and conditions that is empty of any kind of fixed, independent self-nature. Recognizing this, there is liberation from the delusion of selves entrapped by causes and conditions and therefore freedom from birth and death, and even freedom to positively engage the selfless interplay of phenomena in the compassionate manner of buddhas and bodhisattvas. Now some Mahayana Buddhists, like Paramartha (499-569), sharply differentiated between the storehouse consciousness as the defiled aspect of mind and the tathagatagarbha as the pure aspect of mind, positing them as the eighth and ninth consciousnesses respectively. However, the Lankavatara Sutra and other Mahayana sutras as well as the mainstream of the Consciousness Only school of Mahayana always maintained that they were really just two aspects of mind, one obscured by adventitious defilements and the others see in terms of its true luminous nature.

In East Asian Buddhism, a work called The Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana that is attributed to Ashvaghosha (c. 1st – 2nd century) and allegedly translated by Paramartha became an immensely popular and influential treatise attempting to clarify the relationship between the enlightened and unenlightened aspects of mind and how Buddhist practice can help people to awaken to the original enlightenment of the tathagatagarbha. In this work, it is taught that through Buddhist practice one can influence the mind positively, purify it, and reveal the inherent purity of mind. Despite using the later Mahayana terminology of tathagatagarbha, storehouse consciousness and even “original enlightenment” the process it describes seems to be very consistent with what was taught by the Buddha in the Two Kinds of Thought and in the passages from the Numerical Discourses. For example:

By virtue of the permeation (vasana, perfuming) of the influence of dharma [i.e., the essence of Mind or original enlightenment], a man comes to truly discipline himself and fulfills all expedient means [of unfolding enlightenment]; as a result, he breaks through the compound consciousness [i.e., the Storehouse Consciousness that contains both enlightenment and nonenlightenment], puts an end to the manifestations of the stream of [deluded] mind, and manifests the Dharmakaya [i.e., the essence of Mind], for his wisdom (prajna) becomes pure and genuine. (Hakeda, p. 41)

After reviewing all of this, I would propose that the oxherding pictures and their verses are attempting to illustrate the recovery of the true luminous nature of mind from its adventitiously defiled aspect in accord with the teachings of the Lankavatara Sutra and The Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana. I would also say that there are actually at least three levels of metaphor involved. On one level there is the process of how our formal practice can mature from a self-conscious striving to a totally spontaneous and effortless freedom. On another level is the maturation of our character in daily life. On the third level there is the gradual purification mind from a defiled to a totally illuminated state. Below is my translation of these verses along with the pictures that D.T. Suzuki provided from Chu-hung’s 1585 edition. I will also append my own reflections on the meaning of these verses. In order to differentiate between the verses and my comments I will put the former in bold.

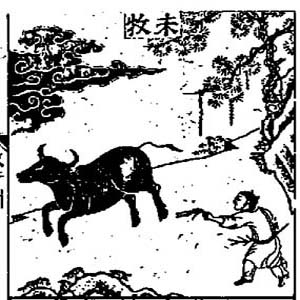

1. Not Yet Herding

From birth, the ox fiercely butts and bellows without restraint.

He hastens through streams and distant

mountain paths.

A sliver of black cloud crosses over

the valley’s mouth.

Who knows how many good sprouts are

trampled with every step?

This verse of course refers to the unrestrained mind full of greed, hatred, and delusion that drags us through the six worlds of hellishness, ghostly craving, beastly impulsiveness, titanic pride, quiet desperation, and heedless complacence. The luminous sun of our originally pure and luminous nature is obscured by the dark cloud of our defilement. Our unwholesome causes stampede over our wholesome ones, like an ox trampling good seeds. This is the human condition whose confusion and anguish may lead us to seek out the Buddha Dharma.

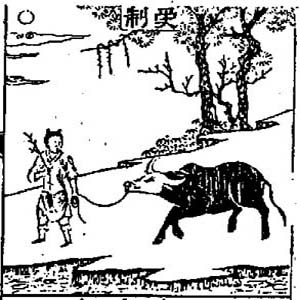

2. Initial Training

With my straw rope I suddenly leap out and pass it through his nose.

At once he turns in haste and fear and

is repeatedly whipped.

From the beginning his vile nature

resists all training and restraint.

Still, the mountain boy fully exerts

himself pulling the ox homeward.

At the beginning of our practice we are not much better off than we were. In fact, we might even seem worse to ourselves because for the first time we are being taught to recognize and try to do something about our negative tendencies and unwholesome causes. The initial practice is probably something very simple, chanting a mantra or just learning to sit still and be mindful of the breath. One may still find oneself slipping back into the kinds of murderous, thieving, deceitful, unfaithful, and intoxicated states of the lower worlds, but the practice keeps our attention and commitment and points us in a new direction – a direction of faith, compassion, insight, generosity, self-restraint, patience, constructive efforts, peace of mind, and liberating wisdom. It is easy to get discouraged and give up, but practice at this stage is not about being perfect but about honestly acknowledging where we are and becoming increasingly determined and confident that we can mature into the higher worlds and ways of being that are characterized by self-development, realization, compassion, and perfect complete awakening. The simple practice that we are given is what we must keep coming back to again and again, whenever we make a mistake in daily life or whenever we find our mind drifting away during formal practice. This is how we get pointed home and make progress, even if it is hard to discern.

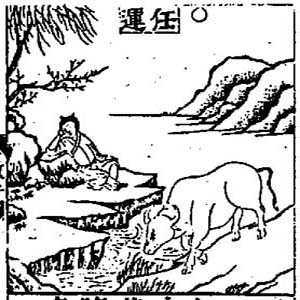

3. Enduring Restraint

Gradually the ox is trained and stops trying to run off.

Crossing over the waters and wearing

clouds he follows.

The boy holds the straw rope without

letting down his guard.

The herd boy is vigilant all day long

without thought of rest.

In time practice becomes a positive, constructive, and consistent part of our daily life. We also find that if we maintain our mindfulness we can keep ourselves from slipping unwittingly into the lower worlds in our thoughts, words, and deeds. Life becomes more manageable and we begin to get at least a conceptual understanding of the Buddha Dharma. This helps, because we start to discern meaning in what before was only confusion and injustice. Still, this is not a time when we can relax our vigilance, nor does conceptual understanding mean that we have any true direct insight of our own. One must guard especially against complacence and pride and continue to make good causes and maintain practice.

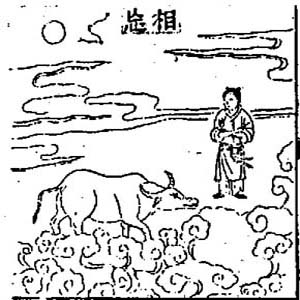

4. Turning the Head

In time, his achievement deepens as the ox turns its head.

It’s unrestrained and willful

mind gradually yielding.

But the mountain boy is unwilling to

trust it completely.

He continues to hold the straw rope to

bind and restrain it.

As practice progresses we find that our willfulness and negativity will decrease. It becomes easier to aim for and maintain one’s equilibrium whether during practice or in daily life. One may still slip up, as the habitual tendencies are still there beneath the surface waiting for their chance to bubble up into consciousness and influence our intentions, words, and deeds for the worse. So vigilance is still required, but it is no longer such a struggle.

5. Tamed and Humble

Under a shady green willow on the bank of an ancient stream,

He finally releases the ox so that it

can follow it’s own nature.

The sun sets on azure clouds over the

fragrant pasture.

The herd boy returns home and no longer

has to pull the ox.

This is much more rarefied state of practice, when one is able to catch a glimpse of the purity of the true nature of mind. Practice becomes more effortless and natural, like coming home from a long and difficult journey. We are finally able to trust ourselves and feel more confident in our practice. There is still some residual defilement, however, so that one is not quite yet at a point where one is fully liberated or awakened. During practice, one finds that unwholesome thoughts no longer trouble one, but many neutral or wholesome considerations may arise. It is at this point that one should not interfere with mind but simply be aware and remain attentive to one’s primary practice.

6. No Hindrance

On the dewy ground the ox sleeps peacefully without concern.

No more toiling with the whip, which is

never taken up again.

The mountain boy sits firmly under the

green pine.

For once playing a peaceful song and

overflowing with joy.

There comes a point during formal practice when the mind stops to chatter and we become joyfully centered on the primary practice. It is a light and even tingly bodily sensation and one feels at ease and happy without necessarily having to consciously reflect on it. In terms of daily life, one must of course take up conscious thinking and feeling, but now behind it is a perspective that flows out of the experience and perspective of one’s formal practice. There are still defilements hidden away in our subconscious, but they are now subdued and no longer actively disrupting our life. One is not yet able to constantly abide in the unconditioned, but now the conditioned world of cause and effect has become more clearer and less threatening as one achieves a tentative inner peace and joy.

7. Fulfilled Destiny

The willows on the bank of the spring stream glow in the setting sun.

A light mist covers the fragrant and

luxurious green grass.

In all seasons they eat when hungry and

drink when thirsty.

On the rock the mountain boy sleeps

deeply without concern.

Here is where practice is no longer a self-conscious effort at all. Even the positive disruption of the feelings ease and joy merge into an even more sublime equilibrium and state of one-pointed concentration. In terms of daily living, one is able to live a simple life, free of attachment and aversion. One is fulfilled and content. The sun that illumines the six worlds sets, indicating that the time of duality is ending.

8. Forgetting All

The white ox constantly abides in the midst of the white clouds.

The man is free of willful thinking and

the ox is also the same.

The moon passes through the white

clouds casting a white reflection.

The white clouds and bright moon are

born from west to east.

The full moon is an indication of buddhahood, but as yet there is a trace of subtle duality keeping the practitioner alienated from it. The practitioner is able to feel a sense of achievement as he reflects on the pure nature of mind. The ox of the mind stands amidst clouds that only reflect the mind. In addition there is still a sense of need for progress as clouds and moon seem to move from west to east, from the place where the sun set on the six worlds to the east where those just beginning their journey to that accomplishment have yet to hear and practice the Dharma.

9. Solitary Illumination

The ox is nowhere to be found and the herd boy is at leisure.

One solitary wisp of cloud drifts among

the azure peaks.

Clapping his hands and loudly singing

below the bright moon,

Returning home he still has one more

crucial gateway to pass.

Now there is a true integration as mind and practitioner are one. The practitioner has gone beyond accomplishment and dualistic watching of the mind, and yet there is still more to be done. The practitioner is now the bodhisattva making his vows and returning to the six worlds to help others. And yet, is this not itself a sign of subtle duality between awakened self and the ignorant masses, between the cloudy peaks and the valley below?

10. Both Disappear

Neither man nor ox are seen, in the darkness there is no trace.

The sky is full of bright moonbeams and

the cold multitude of stars.

If you ask for a logical explanation

for all of this, just behold:

The wild flowers, fragrant grasses, and

nature’s crowded thickets.

Here everything is overcome and there is no more duality as the true nature shines forth unhindered. The bodhisattva has returned home because he was always home. There is no ox, no practitioner, no awakened, no ignorant. All things are just as they are. There is nothing that needs to be added and nothing that needs to be taken away. Here is just the full moon shining equally, spontaneously, and without any contrived effort. This is the sheer luminosity of perfect and complete awakening compassionately radiating all skillful means.

Sources

Chung, Bongkil, trans. The Scriptures of Won Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2003.

Hakeda, Yoshito S., trans. and comm. The Awakening of Faith: Attributed to Asvaghosha. New York: Columbia University Press, 1967.

Nanamoli, Bhikkhu and Bodhi, Bhikkhu, trans. The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha: A New Translation of the Majjhima Nikaya. Botson: Wisdom Publications, 1995.

Nyanaponika, Thera and Bodhi, Bhikkhu trans. & ed., Numerical Discourses of the Buddha: An Anthology of Suttas from the Anguttara Nikaya. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, 1999.

Suzuki, D.T. Manual of Zen Buddhism. New York: Grove Press, 1934 (reprinted).

Suzuki, D.T., trans. The Lankavatara Sutra: A Mahayana Text. Taipei: SMC Publishing Inc., 1994.