Terebess

Asia Online (TAO)

Index

Home

Gary Snyder (1930-). Selected Poems

Gary Snyder, Zen Master

A beat irodalom: Gary Snyder magyarul

Haikui Terebess Gábor fordításában

Gary Snyder's Haiku

A young

Gary Snyder on the porch of

Shoden-ji Rinzai temple

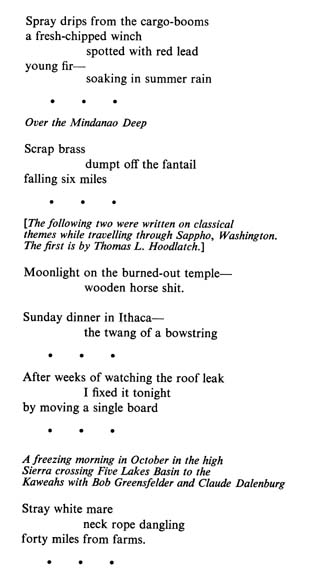

Hitch Haiku (1965)

They didn't hire him

so he ate his lunch

alone:

the noon whistle

* * *

Cats shut down

deer thread

through

men all eating lunch

* * *

Frying hotcakes in

a dripping shelter

Fu Manchu

Queets Indian Reservation in the rain

* * *

A truck went by

three hours ago:

Smoke Creek desert

* * *

Jackrabbit eyes all night

breakfast in Elko.

* * *

Old kanji hid by dirt

on skidroad Jap town walls

down the hill

to the Wobbly hall

Seattle

* * *

Spray drips from the cargo-booms

a fresh-chipped winch

spotted with red lead

young fir—

soaking in summer rain

* * *

Over the Mindanao Deep

Scrap brass

dumpt off the fantail

falling six miles

* * *

[The

following two were written on classical

themes while travelling through Sappho, Washington.

The first is by Thomas L. Hoodlatch.]

Moonlight on the burned-out temple—

wooden horse shit.

Sunday dinner in Ithaca—

the twang of a bowstring

* * *

After weeks of watching the roof leak

I fixed it tonight

by moving a single board

* * *

A

freezing morning in October in the high

Sierra crossing Five Lakes Basin to the

Kaweahs with Bob Greensfelder and Claude Dalenburg

Stray white mare

neck rope dangling

forty miles from farms.

* * *

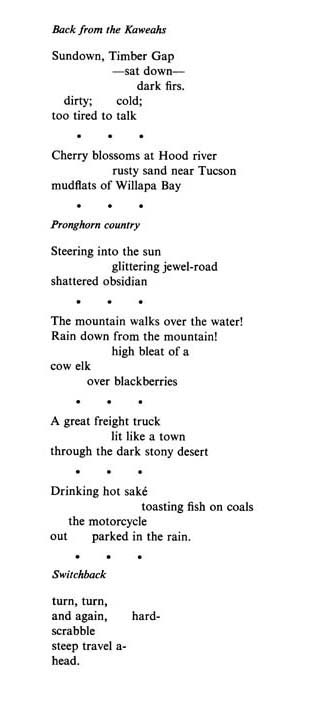

Back from the Kaweahs

Sundown, Timber Gap

—sat down—

dark firs.

dirty; cold;

too tired to talk

* * *

Cherry blossoms at Hood river

rusty sand near Tucson

mudflats of Willapa Bay

* * *

Pronghorn country

Steering into the sun

glittering jewel-road

shattered obsidian

* * *

The mountain walks over the water!

Rain down from the mountain!

high bleat of a

cow elk

over blackberries

* * *

A great freight truck

lit like a town

through the dark stony desert

* * *

Drinking hot saké

toasting fish on coals

the motorcycle

out parked in the rain.

* * *

Switchback

turn, turn,

and again, hard-

scrabble

steep travel a-

head.

Hitch Haiku

From The Back Country, 1967

Hiking in the Totsugawa Gorge

pissing

watching

a waterfall

---------------------------------------------------

Gary Snyder

Lookout's Journal

From Earth House Hold, 1957

the

boulder in the creek never moves the water is always falling together!

This

morning: floating face down in the water bucket

a drowned mouse.

leaning

in the doorway whistling a chipmunk popped out listening

a butterfly scared up from its flower caught by the

wind and swept over the cliffs

Skirt

blown against her hips, thighs, knees hair over her ears climbing the steep

hill

in high-heeled shoes

------------------------

Gary

Snyder

Danger on Peaks: Poems

Washington, D.C.: Shoemaker & Hoard, 2004. 110 pages

There are exemplary haiku in Gary Snyder’s Danger on Peaks, such as “Cool Clay” (28), “Catching grasshoppers for bait” (35), “Warm nights” (37), and many more.

Hammering a dent out of a bucket

a woodpecker

answers

from the woods

In a swarm of yellowjackets

a squirrel drinks water

feet in the cool clay, head way down

Nap

on a granite slab

half in shade, you can never hear enough

sound of

wind in the pines

Catching grasshoppers for bait

attaching them live to the hook

—I

get used to it

a certain poet, needling

Allen Ginsberg by the campfire

“How come they all love you?”

Clumsy

at first

my legs, feet, and eye learn again to leap

skip through the jumbled rocks

Tired, quit climbing at a small pond

made camp, slept on a slab

til

the moon rose

Warm

nights,

the lee of twisty pines—

high jets crossing the stars

------------------------

News of the Day, News of

the Moment

Gary Snyder talks with Udo Wenzel

Udo Wenzel: Unlike to the haiku in English the German haiku scene made its first experiences with the so called "free-format haiku" only a few years ago. Since that time it is an unanswered question how to define a haiku or how to distinguish it from other lyrics and poetry styles. You started more than 50 years ago to write haiku. And from the beginning you didn’t pay attention to the most common definition of what a haiku is or might be: 5-7-5 syllables-counting and the required use of a seasonal word. How did this happen?

Gary Snyder: I have never called my brief poems "haiku" except in certain rare cases where a brief poem met what I felt were the key aesthetic requirement of a top quality haiku — which means among other things, freedom from ego. I do not think we should even "think" haiku in other languages and cultures. We should think brief, or short poems. They can be in the moment, be observant, be condensed and meaningful, detached or not, or have many other possible qualities except perhaps satire, parody, anger, and such. That territory belongs, in Japanese, to "Senryu."

I don't think counting 5,7,5 syllables is necessary or desirable. To reflect the natural world, and the season, is to reflect what is. Many modern haiku in Japan won't have a kigo, a "season word."

Udo Wenzel: Do you believe that the haiku at heart is not portable into other languages and cultures? Do you think, the American or European Haiku is a “sham package”?

Gary Snyder: As I am trying to say, the haiku is a Japanese poetic form. It has elements that can indeed be developed in the poetries of other languages and cultures, but not by slavish imitation. To get haiku into other languages, get to the "heart" of haiku, which has something to do with Zen practice and with practiced observation -- not mere counting of syllables.

Udo Wenzel: In 1956, after you had left the North American West-Coast and the community of beat poets, you moved to Japan, where you lived for the next twelve years, studying Chinese and Japanese language and receiving teachings in a Zen-monastery. Did you come in touch with haijins? What would you say, did your view of haiku change, as you faced it in its origin country?

Gary Snyder:I met no haiku poets with the exception of Nakagawa Soen Roshi at his temple near Mt. Fuji. I stayed there two nights, and went for a walk with him up the mountain. We never talked about poetry. Later I learned he was a very highly regarded haiku poet as well as a Zen Master. Some of the Zen monks down in Kyoto thought little of him, saying "If he was serious about teaching Zen he wouldn't be always going to those haiku poet meetings in Tokyo."

I didn't have a fixed view of haiku when I went there so I can't say it changed.

Udo Wenzel: It is well known that you are not a Haiku Poet primarily, but you have used haiku within prose (it reminds me of the tradition of Bashô’s haibun). Above all you’ve integrated haiku within longer poems. Did you have literary models für this technique?

Gary Snyder: I have certainly integrated tough, stand-alone brief image-poems that carry a load of meaning within my longer poems. I don't call them haiku. It's part of my poetic strategy. It owes something to haibun, but also to aspects of various oral traditions where songs are woven into the storytelling (and such oral performance is not "prose.")

Udo Wenzel: Could you please give us your definition of what a haiku is?

Gary Snyder:A haiku is a short Japanese poem that is both very easy and extremely difficult to do. Huge numbers of people all over the country write them daily. Many are in the newspapers. They have a set of rules and guidelines which are not followed slavishly. It is hard to appreciate haiku fully in translation because much of their power is in the tricks done with the syntax. Although the greatest haiku are among the finest utterances in the world, the huge number of lesser haiku play a valuable and enlivening role in the culture. Non-Japanese societies can learn from this tradition and feel free to write brief poems that are strong "news of the day, news of the moment" – and fundamentally without ego.

Udo Wenzel: Who writes, if a haiku is written without ego? Would you please explain, what does it mean to write without ego. How can one recognize such a haiku? Could you give us an example?

Gary Snyder: Hakuin Zenji's "Song of Meditation" has the line "true nature that is no-nature, far beyond mere doctrine." Dogen Zenji says, "We study the self to forget the self." No nature is true nature, non-ego is the mysterious power of creation. How do you recognize such a haiku and what are examples? Just remember the great haiku from the Japanese tradition that first made you fascinated with haiku when you were fresh to the field, poems by those we call "the masters."

Udo Wenzel: Even though the Japanese Haiku could be better described as seasonal poetry than as nature poetry, nature and landscape were always in the core of haiku poetry. In Dharma Bums one could read, in which kind you created haiku in the fifties. Following oral poetry traditions, you called out the haiku to each other on hikings and you did not write it down. I suppose this discounts the aspect of Japanese haiku being lingustic works of art, as we know, the haijins polished it often for a long time. What would you say today, which value has language in haiku poetry?

Gary Snyder:You can't call out, sing, speak, write or say any song or poem without language. Language always has syntax. Some people have a talent for language more than others. To get good at language you have to listen a lot.

Udo Wenzel: In your writings you often turn against conventional dichotomies, for example against the dichotomy between nature and language/culture order nature and civilisation. On the one hand you extended the term of nature into the human realm, on the other hand „wilderness“ is an important concept for you. What is their part related to poetry?

Gary Snyder:My prose book of ecological philosophy,"The Practice of the Wild", has detailed explication of these questions, and careful definitions of the words "nature" and "wild" (which should be understood as not identical with "wilderness.") Hanfried Blume has recently finished his German translation of this book and it will be published by Matthes and Seitz press in the coming year.

Udo Wenzel: For the haibun „The Narrow Road to the Deep North„ Bashô visited during his long journey the so-called utamakura ("poem pillows"), places which were already enriched with cultural and literary meanings, and he wrote about them in a fresh and fancy manner. You often described in your poems and prose the landscapes of the North-American West. One of your main projects is „Mountain and River Without End“. In what way are you influenced by Bashô?

Gary Snyder:"Mountains and Rivers Without End" was finished in 1996. Bashô was an earlier influence for me but so was Buson. The biggest single literary influence on this long poem was Noh drama, in particular the play "Yamamba".

Udo Wenzel: Once you labeled yourself as a „Buddhist poet“. How would you personally describe the connection between religion and poetry?

Gary Snyder:I like what the Zen Master Dôgen said in the 13th century. "We Study the Self to forget the Self. When you forget the Self you become one with the entire phenomenal world."

Udo Wenzel: Did you write poems which are close to haiku recently? Would you kindly present some of it?

Gary Snyder:The place best to find my recent short poems and "haibun-like" poems is in my recent volume of poetry called "Danger on Peaks". This was recently translated into German published by his Stadtlichter Press. Sebastian Schmidt (transl.) Gefahr auf den Gipfeln (Berlin: Stadtlichter Presse, 2006). This has a block of very short poems, and also a whole section called "Dust in the Wind" which has prose-block plus brief poem.

Here's a recent brief poem:

Ravens in the afternoon control-burn smoky haze

croaking ........ away.

Coyotes yipping in the starry early dawn.

Udo Wenzel: Thank you very much for the interview.

------------------------

Gary Snyder

from "The Path to Matsuyama"

Modern Haiku 36.2, Summer 2005.

On Receiving the Masaoka Shiki International Haiku Grand Prize

from the Ehime Cultural Foundation, in Matsuyama City, Japan,

November 7, 2004

I was from a proud, somewhat educated farming and working family. After finishing

college I went back to work. I went into the National Forests to be an isolated

fire lookout living in a tiny cabin on the top of a peak. I worked as a

summertime firefighter and wilderness ranger, and then spent winters in San

Francisco to be closer to a community of writers.

I discovered the four-volume set of haiku translations by R. H. Blyth that now we all know so well. Reading the four Blyth volumes gave me my first clear sense of the marvelous power of haiku. (The other reading of that era that helped shape my life was books by D.T. Suzuki.) I lived with Blyth’s translations for a long time, and began to be able to see our North American landscapes in the light of haiku sensibility (which of course includes the human.) When I ran across Bashô’s great instruction “To learn of the pine tree, go to the pine” my path was set.

In the fall of 1953 I moved to Berkeley and entered as a graduate student in East Asian Languages at the University of California. I read Chinese poetry with Dr. Chen Shih-hsiang and translated poems of the Chinese Zen poet Han-shan/Kanzan. I studied Japanese with Dr. Donald Shively.

This was 1954. Through Dr. Shively I got to know the formidable American Buddhist scholar Ruth F. Sasaki, who had been married to the Japanese Zen Master Sasaki Shigetsu. They had met before World War II when he was teaching Rinzai Zen in a little zendô zend in New York City. He died during the war. Mrs. Sasaki returned to Kyoto after the war to continue her Zen training with Sasaki Shigetsu’s Dharma brother Gotô Zuigan Roshi. She was also hard at work translating and publishing Zen texts. She offered to help me get to Kyoto, saying that it would deepen my knowledge of Japanese and Chinese, and give me an opportunity for first-hand Rinzai Zen practice. Just as I was preparing to leave the West Coast I got involved with the literary circles that are now remembered as the “Beat Generation” in San Francisco. I participated in poetry readings and had some minor publications. Those early poems already show the influence of haiku with strong short verses contained within longer poems. This was a strategy that came to me through W.C. Williams and Ezra Pound.

I first arrived in Japan in May of 1956. Exposure to Buddhist scholars and translators soon brought me to the Zenrinkushu, that remarkable anthology of bits and pieces of Chinese poetry plus a number of folk proverbs as they became used within the Zen world as part of the training dialog. If one was looking at the possibilities of “short poems” the Zenrinkushu practice of breaking up Chinese poems would certainly have to be included. R.H. Blyth famously said “The Zenrinkushu is Chinese poetry on its way to becoming haiku.” Maybe it is that somebody — one of the old Zen monk editors — realized that practically all poems are too long and that they’d be better if they were cut up. So he cut up hundreds of Chinese poems and came out with new, shorter poems! I now know I was extremely fortunate to have been exposed to the elegant “Zen culture” aspects of Kyoto. But as I traveled around Japan I came to thoroughly appreciate popular culture, ordinary people’s lives, and the brave irreverent progressive vitality of postwar Japanese life. I realized that the spirit of haiku comes as much from that daily-life spirit as it does from “high culture” — and still, haiku is totally refined.

One of my

friends from early Kyoto days was Dr. Burton Watson. He was on Mrs. Ruth

Sasaki’s translation team at Daitôku-ji in the late fifties, working on Zen

texts, as well as his own projects. I joined that team as an assistant. He has lived in Japan almost continuously since that time,

maintaining affiliations with Columbia University. He is without question the

world’s premier translator from both Chinese and Japanese into English. Only

long years of friendship allow me to call him Burt. Though I had read

translations of Shiki before, it was Dr. Watson’s versions of Shiki published

by Columbia

University Press in 1997 that enabled me to fully appreciate him. Janine

Beichman wrote Masaoka Shiki: His Life and Works, first published in

1982, but I didn’t read Beichman’s book until after my exciting exposure to

Shiki through Dr. Watson. We English/American language speakers are fortunate

to have these two excellent books to give us access to a man who was a giant in

the world of haiku poetry. (Watson did a volume of translations of

another poet of Matsuyama City, Taneda Santôka, that was also published by

Columbia University Press, in 2003. It is titled For All My Walking. It

is a Walking delightful volume.)

I continued to live and study in Kyoto until 1968. My ability to speak and read Japanese improved a bit, though I am still embarrassed by how clumsy I am with this elegant language. I managed to read haiku in the original just enough to comprehend that the power of haiku poetry is not only from clear images, or vivid presentation of the moment, or transcendent insight into nature and the world, but in a marvelous creative play with the language. Poetry always comes down to language — if the choice of words, the tricks of the syntax, are not exactly right, whatever other virtues a piece of writing might have, it is not a poem. (These are the standards we apply to poetry in each our own language. Poems in translation of course can not be judged this way. “Images” however are translatable.)

I returned to North America in 1968 (Some of us prefer to call it “Turtle Island” after Native American creation stories). In 1970 I moved with my family to a remote plot of forest land in the Sierra Nevada at the 1,000-meter elevation — pine and oak woods. We built a house and have made that our home base ever since.

Having a

“home base” for my wife and family made it possible to go on periodic trips

over the years doing lectures, readings, and workshops. Honoring the haiku

sensibility, I look for what would be the seasonal signals, kigo, in our

Mediterranean middle-elevation Sierra mountain landscape. What xeric aromatic

herbs and flowers, what birds, what weather signals, will we find? They are

different from Japan. I read translations of the myths and tales of the Native

people who once lived where I live now, from the Nisenan language

(which is no longer spoken) and I can see how much

they valued the magic of the woodpecker, the sly character of fox, and the

trickster coyote. High-flying migratory sandhill cranes pass north and south in

the spring and in the fall directly over my house. They have been doing this

for at least a million years.

The Euro-, African-, and Asian-Americans are just a little more than 200 years on the west coast of North America, and it will be several centuries yet before our poetic vocabulary matches the land. The haiku tradition gives us the pointers that we need to begin this process, which will be part of making a culture and a home in North America (and I hope eventually, for all people, a home on planet earth) for the long future ahead.

The ancient Buddhist teaching of non-harming and respect for all of nature, (which is quietly present within the haiku tradition) is an ethical precept we are in greater need of now than ever, as the explosive energy of the modern industrial world pushes relentlessly toward an endless exploitation of all the resources of the planet.

Now I want to go back to talking about how Japanese haiku poetry has been discovered world-wide. Up till now I have been speaking of haiku as it exists in Japan from early times up to the present. Though haiku may be considered old fashioned and conservative by some people in Japan, in the rest of the world it is received as fresh, new, experimental, youthful and playful, unpretentious, and available to students and beginners who want to try out a poetic way of speaking.

As we all know there’s scarcely a literate culture on earth that doesn’t have some translations of Japanese haiku in its poetry anthologies. From this, an international non-Japanese haiku movement has begun, which takes the idea of haiku hundreds of new directions. School teachers in Denmark, Italy, or California have no hesitation giving translations of Japanese haiku to their students, and then also reading locally-written brief poems to them, telling the children to look around, see what they see, have a thought, make an image, and write their own brief poem. Children everywhere are learning about poetry and themselves just this way. Though this may not be entirely true to the haiku tradition itself, it is of immense value to young people to have their language and imagination liberated. Short poems and haiku inspire them more than the usual English or European-language poetry which always seems (to children) either too metrical and formal or too modern and experimental.

The haiku tradition is now part of a world-wide experimental movement in freshly teaching poetry in the schools. This is another reason to celebrate haiku. As a teacher in the graduate creative writing program at the University of California at Davis, I taught the haiku tradition to older students on a serious poetry-writing track, using Robert Hass’s superb book The Essential Haiku, and it was as surprising and useful to these sophisticated young adults as to any schoolchild. Haiku amazingly reaches every class, every age.

Eventually somehow I became known as a poet. My poetic work has had many influences: Scotch-English traditional ballads and folksongs, William Blake, Classical Chinese poetry, Walt Whitman, Robinson Jeffers, Ezra Pound, Native American songs and poems, haiku, Noh drama, Zen sayings, Federico Garcia Lorca, and much more. The influence from haiku and from the Chinese is, I think, the deepest, but I rarely talk about it. Though not a “haiku poet” I have written a number of brief poems, some of which may approach the haiku aesthetic. They also fit into a larger project which I call “Mountains and Rivers Without End” in which I am searching for ways to talk about the natural landscapes and old myths and stories of the whole planet. I am sure I have bitten off far too much, and my poetry might be better if someone just cut it up into little pieces.

Over the years I have made many trips to Japan, and continued to learn from contemporary Japanese poets, especially Tanikawa Shuntarô, Ôoka Makoto, and Sakaki Nanao — Nanao is a truly unique figure. The contemporary Korean poet Ko Un’s very short Zen (Korean Son)–inspired poems are hugely pleasurable and very subtle. I enjoyed getting to know the haiku of Dr. Arima Akito through the translations of Miyashita Emiko and Lee Gurga.

Before I wind this up, I want to share with you the pleasure I take in a just a few of Masaoka Shiki’s haiku (I could cite many more.) For example,

inazuma ya / tarai no soko no / wasure-mizu

Lightning flash—

in the bottom of the basin,

water someone forgot to throw out

—which I remember almost every time I bend over and wash my face, hoping for a flash of light ! —and,

yuki nokoru / itadaki hitotsu / kuni-zakai

A single peak,

snow still on it—

that’s where the province ends

because from where I live (which is in the mountains of California) there is a mountain not too far to the east forever with springtime snow. I always think “beyond that is the desert state of Nevada” — and remember Shiki. But perhaps most interesting for me is this:

nehanzô / hotoke hitori / waraikeri

Picture of the Buddha

Entering Nirvana

One person is laughing !

When I was a Zen student in Kyoto my teacher once gave me a little testing koan which was “In the Buddha’s Nirvana-picture, everyone is crying. Why are they crying?” Some years later I find Shiki’s nehanzô haiku and I can never stop laughing. What a fresh mind he had ! (All the above translations are by Burton Watson.)

To finish up: Yves Bonnefoy in his excellent presentation here in 2000 said that we in the Occident are not experiencing “a kind of haiku fashion” but an awakening to a necessary and fundamental reference, which can only remain at the center of Western poetic thought.” And he goes on to say, that all these exchanges are for the “greater good of poetry, which is our common good and one of the few means that remain for preserving society from the dangers that beset it.”

It is quite to be expected that Mr. Bonnefoy and myself, French and American, each in our own way, invoke haiku as a benefit and a value in matters of the troubled world today. People are always asking “what’s the use of poetry?” The mystery of language, the poetic imagination, and the mind of compassion, are roughly one and the same, and through poetry perhaps they can keep guiding the world toward occasional moments of peace, gratitude, and delight. One hesitates to ask for more.

http://www.modernhaiku.org/issue36-2/GarySnyder.html