Terebess

Asia Online (TAO)

Index

Home

正岡子規 Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902)

![]()

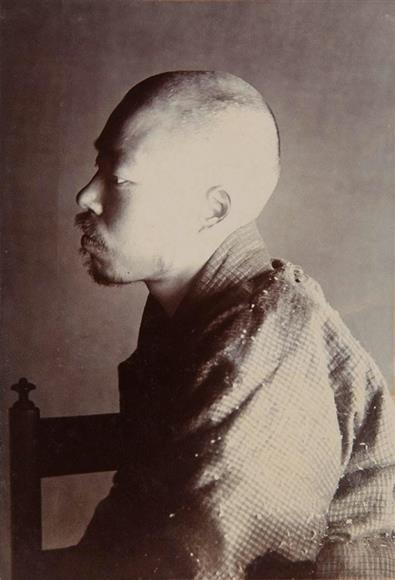

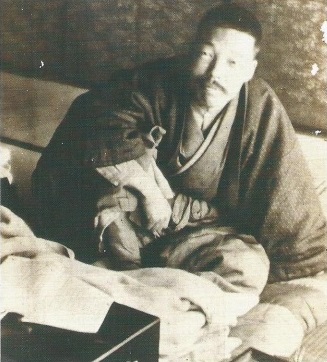

Shiki's last portrait, December 24, 1900. Photo: 正岡明 Masaoka Akira

![]()

子規の俳句

http://www.aozora.gr.jp/index_pages/person305.html#sakuhin_list_1

http://www5c.biglobe.ne.jp/n32e131/haiku/siki.html

http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/japanese/shiki/beichman/BeiShik.utf8.html

http://www.webmtabi.jp/200803/haiku/matsuyama_masaokashiki_index.html

https://www.city.matsuyama.ehime.jp/shisetsu/bunka/sikihaku/sikihakuriyou/shikihaiku_kensaku.html

子規は、その長くはない生涯で約24,000もの俳句を作りました。(抹消句等を含みます)

その子規の俳句を、春、夏、秋、冬、新年、雑 に分類して掲載しました。

季語での検索もできますので、ぜひ覗いてみてください。出典:『季語別子規俳句集』 編集・発行 松山市立子規記念博物館

年代 Date 季節 Season 分類 Classification (plants, animals, human, astronomy etc.) 季語 Kigo (seasonal word)

子規の俳句検索

http://sikihaku.lesp.co.jp/community/search/index.php

指定管理者株式会社(レスパスコーポレーション)のホームページで、句中曖昧語、年代、季節、分類、季語の5つの検索方法で絞り込んで検索できるようになりましたので、こちらもご利用ください。

![]()

Biography

1867:

Born in Matsuyama Castle Town (present Matsuyama-city) on September 17.

1883:

Went to Tokyo where his uncle lived.

1884:

Entered Tokyo University Preparatory School.

1888:

Entered the Tokiwa Kai Dormitory of the Matsuyama Domain, Hisamatsu Clan. Expectorated blood for the first time.

1889:

Expectoration of blood lasted for a week. Began calling himself" Shiki ".

1890:

Entered into the Philosophy Department of The College of Liberal Arts of Imperial University, and later transfered to the Japanese Literature Department.

1892 :

Wrote travel writings and stories about haiku in the newspaper, Nihon. Contracted tuberculosis.

1893:

Withdrew from the university.

1895:

Traveled to Kinshu, Qing as a war correspondent in the Sino-Japanese War. On his way back to Japan, spit up blood and returned to Matsuyama for recuperation. Stayed in the lodging, Gudabutsu An, where a Matsuyama East High School Teacher, Natsume Soseki (later to be a famous author in his own right) was also staying, and started his reform of haiku with members of Shofu Kai.

1896:

The tuberculosis was complicated by spinal caries.

1897:

Became involved in publishing the haiku magazine, Hototogisu (Cuckoo) in Matsuyama.

1898:

Wrote Utayomi ni Atauru Sho (Book for poets), advocating the necessity of reforming Tanka. Held poetry study meetings on the poetry anthology, The Anthology of Myriad Leaves.

1900:

Held a writing study group, Yamakai, advocating " Shaseibun (highly descriptire writing style)".

1902:

Died on September 19 at 36 years old. Laid to rest at Dairyiiji Temple in Kita-ku, Tokyo.

SHIKI: The Discovery

of Haiku

Source:

http://shiki.toward.co.jp/~kim/masaoka1.html

In

1868 Japan launched into a civilized society from the feudal age. Western culture

had a great effect on it and civilization rapidly developed modern culture.

In the previous year 1867, Masaoka Shiki was born in Matsuyama. His father served

the Matsuyama domain in the lower rank of samurai. Shiki lived to be 35 years

old and died of tuberculosis of spine in 1902. In his last seven years, he had

to be confined to his bed; however, during that time he accomplished three of

his great works on modern literature: Haiku Reform, Tanka reform, Advocating Sketch-from-Life-Prose.

1. Shiki's Discovery of Literature

When Shiki was in the fifth grade he composed a Chinese poem.

聞子規

一声弧月下 啼血不堪聞

半夜空欹枕 故郷万里雲

Under the moonlight, cuckoo cried as if it coughed up blood.

The sad voice kept me waking up,

the cry reminded me of my old home town far away.

(It is said that a Japanese cuckoo, hototogisu, 子規 (Shiki) will sing until it coughs out blood because of its sad voice.)

In those days Chinese poetry and prose were considered as important learning and culture, so even young children used to compose them. The interesting thing about this young Shiki's Chinese poem is that he composed on a sad voice of cuckoo which would cough up blood. Later he was to cough out blood and he picked out his pen name, 子規 (Shiki) a hototogisu. Shiki wrote about 900 Chinese poems in his life.

Shiki's name in his own handwriting

Shiki's name in his own handwriting

At the age of 15, Shiki began to composed tanka with 31 Japanese letters of 5-7-5-7-7 syllables. He composed about 2300 tanka in his life.

2. Interest in Haiku

野のみどり搗き込みにけり草の餅

green in the field

was pounded into

rice cake

草餅 a green herb rice cake is made of rice pounded in a mortar with steamed leaves of mugworts. The expression ' green in the field is pound into rice cake' was interesting, but overuses the images.

When he was 22, he coughed out blood. He changed his name to Shiki,which is an another name for the bird a Japanese cuckoo 'hototogisu'. Since those days, he was inspired by his uncle, haiku teacher Ohara Kiju. He began to devote himself into haiku. Shiki composed over 25,500 haiku in his short life. After Ohara Kiju passed away, he began to classify old haiku according to season words. At that time there were several ways of using season words and they were different according to writers. For instance, there were many kinds of 'tofu' : cold tofu, yu-dofu (a simmered hot water tofu), etc. So he began to consider what season each word should express.

3. Haiku as a Sketch of Life

When he was 24, he had 3 day walk around Musashino ( fields around present Warabi-shi and Kumagawa-shi in Saitama Prefecture where there used to be lots of rice paddy fields and forests.) at the end of the year 1891, when he realized that word play would not enough to express the truth and that we should write things as they are. He had an open-eye to haiku for the first time. He composed:

凩や荒緒くひこむ菅の笠

cold winter blast

a cord of a sedge hat

cut into my neck夕日負ふ六部背高き枯野かな

the sun set behind

a traveling monk

tall in the withered field

Next year in 1892 he went to a hill ,Takao-san in the western suburbs of Tokyo and composed the following haiku:

麦蒔や束ねあげたる桑の枝

wheat sowing

the mulberry trees

lift bunched branches松杉や枯野の中の不動堂

pine and cypress

in a desolate filed

a Fudodo shrine

He wrote a simple haiku from a simple common sight. This was a new experiment and discovery of new material and vision. Then he composed another sketch haiku in 1894.

低く飛ぶ畦の螽や日の弱り

locusts fly low

over rice paddies

in the dim sun ray赤蜻蛉筑波に雲もなかりけり

red dragon fly

in the sky of Tsukuba

no cloud

The former haiku has a very close eye to the insects and the latter one expresses a very spacy field with a dragon fly focused.

4. Shiki in Matsuyama

At the age of 28 he returned to Matsuyama and spent over 50 days recuperating from tuberculosis with Soseki Natsume, one of his best friends and a very famous author. Soseki was in Matsuyama as a teacher of English at Matsuyama Middle School. Soseki was living at Gudabutsuan, where many Shiki's friends visited. Soseki and town people were quite inspired with Shiki's new type haiku. They gathered around him every night to hold haiku meetings. They also enjoyed writing haiku while taking a walk. Shiki composed this haiku when they paid a visit to Ishite Temple, the 51st pilgrimage temple.

見上ぐれば塔の高さよ秋の空 composed on September 20 in 1895.

looking up

what a high pagoda

in the autumn sky

This haiku just has a right direct expression of the great three storied pagoda, soaring to the clear autumn sky.

At Hojoji Temple,where Buddhism Ji-sect founder Saint Ippen was born, he composed:

色里や十歩はなれて秋の空

a gay quarter

just ten steps away

autumn breeze

Just near the temple there used to be a gay quarter.

Also he composed another haiku at Dogo Hot Spring from the building of Dogo hot spring spa, which is very near the temple.

柿の木にとりかこまれたる温泉哉

by persimmon trees

surrounded

hot spring

From the 3rd floor of the main building of Dogo hot spring spa, we see the castle to the west, rice paddies beyond and hot spring quarters, where each house had persimmon trees in the yard. They were astringent persimmons. We remove the astringency of persimmons with low-class distilled spirits, 'shochu'. We spray 'shochu' over them until they become sweet, Shiki loved this sweetened persimmons very much. As for his haiku appreciation, that haiku describes only visible scene, and to tell the truth, we may say it is not so good a haiku. Shiki could have eaten up 15 or 16 of the sweetened persimmons at one time. So persimmon trees might have attracted Shiki.

5. Haiku Reform

Through his haiku exercise, he studied how to improve haiku and wrote a theoretical text on haiku literature, 'Haiku Taiyo', The Element of Haiku.

At this time haiku was considered to be a low rank literature. It used to be composed in the hangout of the barbers or rikisha-men. But Shiki's 'Haiku Taiyo' inspired people and they began to think better of haiku.

Shiki composed more haiku:

水草の花まだ白し秋の風

water plant blossoms

still white

autumn windひょっと葉は牛が喰ふたか曼珠沙華

I wonder

a cow has eaten up the leaves

a spider lily松山の城をのせたり稲むしろ

Matsuyama Castle

lifted over the mats

of rice fields

In the traditional Japanese literature, people used to attach much importance to 'yugen' and 'wabi'. 'Yugen' is the subtle and profound quiet beauty and 'wabi' is quiet refinement. These concepts are based on imagination. But Shiki made much use of realism as a methodology and also hit upon an idea of sketch, a technique of drawing and then proposed the philosopher Hegel's theory of "Aufheben", Sublimation as a true literature. He thought of how to use the selection of combination with realism. He advocated 'the 3rd literature; Non imaginary and non realistic literature'.

On his way to Tokyo, he dropped in at Nara, and composed the best known haiku.

柿食へば鐘が鳴るなり法隆寺

I bite a persimmon

the bell tolls

Horyu-ji Templewhenever I bite a persimmon a bell tolls Hōryū-ji Temple

the temple bell rings

(version by Debra Woolard Bender )

as I eat a persimmon--

Hōryū-ji

(version by Paul Conneally )

taste of persimmon

as sharp as the bells

Hōryū-ji

(version by Laurene Post)

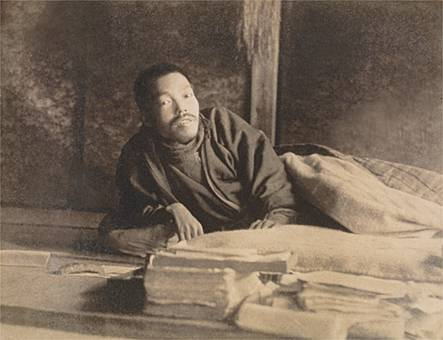

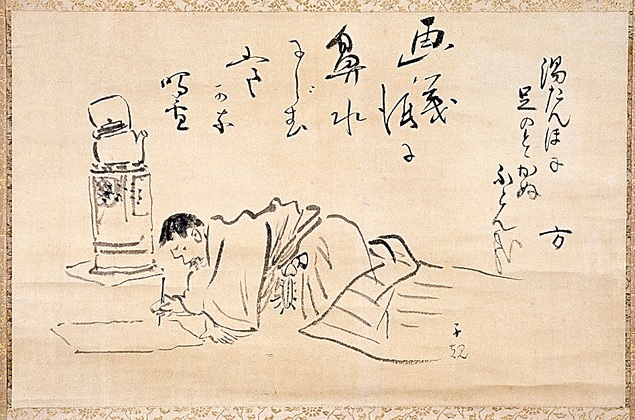

Sick in bed, drawing by Shiki

Shortly after, he suffered much agonized pain and had to be confined to his sick bed for seven years. Although he was a newspaper correspondent at Nihon Shinbun newspaper company, he could not get to work. During that painful period in bed, he initiated his haiku and tanka reform.

6. Some Interesting Haiku

Let's appreciate some of his interesting haiku:

猫恋 (in 1896)

内のチョマが隣のタマを待つ夜かな

Title: Cat's Love

My cat Choma

waiting for neighbor's cat Tama

at night.

This haiku is humorous and it contains the real cats' names 'Choma' and 'Tama'.

いくたびも雪の深さを尋ねけり

many a time

asking the height of

the snow

Since there was not so much snow in Matsuyama, Shiki might have been interested in the snow and he was curious about snow like a child. He kept such innocent spirit of a child.

幼子や青きを踏みし足の裏 (in 1898)

an infant

steps on the green grass

barefoot

This green grass haiku evokes us of the touch of the child's barefoot on the green grass.

この頃の蕣藍に定まりぬ

at this time

morning glories fix the color

deep blue

The summer is advancing and the color of the morning glories has become most blue.

林檎くふて牡丹の前に死なん哉

I eat green apples

facing to peonies

I will die

In this peony haiku, both 'green apples' and 'peony' are summer season words. It is usually said we should not use two season words because the haiku will be out of focus with two images. But this haiku is beautiful and it describes Shiki's character very well. Shiki liked fruit very much. When he wrote the haiku, he had eaten apples to his heart content, thinking of the famous traditional haiku master Buson, who composed famous beautiful haiku on peonies. Also Shiki believed Buson was the greatest haiku poet that people should follow his way.

Shiki's characteristic realism is not such realism as observing things merely objectively but a value of realism appreciating the objects profoundly and reaching a mental state of accepting just as they are, a state of simplicity.

7. Shiki's Curiosity and Humor

At the age of 34, his friend bought a new record player and they listened to Western Laughing Songs. In no time Shiki composed a humorous poem.

crows come flying

scatter their dropping

on a man Gonbe, on the head,

a-ha-ha! a-ha-ha! a-ha-ha! . . . . . . . (in 1901)

In spite of his pain, he still seems to have had such sense of humor. Everyday he had high fever. He was thirsty. Then he composed:

春深く腐りし蜜柑好みけり (in 1901)

full of spring

rotten oranges

how sweet!

He still devoted himself to eating fruit. Writing and eating were only his pleasure in his sick bed. He submitted his article to the newspaper every day.

He was tortured by pain, but when morphine could mask the main, he enjoyed painting.

While the death is closing to Shiki, he composed a haiku on a cicada.

ツクツクボーシツクツクボーシバカリナリ

a late summer cicada

at the top of his voice

chirping, and chirping . . . . . . .

The image of the life of the cicada overlaps his fate close to death.

8. Deathbed Haiku

On the morning of September, with the assistance of Hekigoto, one of his successor who was nursing him and his sister Ritsu, he wrote down three final haiku.

糸瓜咲いて痰のつまりし仏かな

sponge gourd has bloomed

choked by phlegm

a departed soul

Sponge gourd vine juice was used to relieve coughing, but it could no longer help Shiki. Death came at one o'clock the following morning. Even sponge gourd, which is not so elegant, became the theme of his haiku. He found the poetic taste in it and took himself for a hotoke buddha (a departed soul).

----------- based on a talk given by Prof. Shigeki Wada, former curator of the Shiki Memorial Museum, for the EPIC 'Hand's On' project.

----------------------------------------------------------

Two Portraits of Shiki by 中村不折 Nakamura Fusetsu (1866-1943)

「病床の子規」

Shiki in sickbed

Shiki's Last Writing

http://www.cc.matsuyama-u.ac.jp/~shiki/kim/newlast3haiku.htmlBecause of a debilitating disease Masaoka Shiki had to be confined to his bed for almost 7 years until he passed away. Despite the pain, he continued writing poems while lying on his back. When Shiki came near to death, one of his disciples, Hekigoto was at Shiki's bedside. Hekigoto wrote about how Shiki wrote his final three haiku as follows.

It was around 10 o'clock on the morning of September 18.

I dipped his old writing brush, whose stem and brush were both thin, full of ink and had him hold it in his right hand.

Then quite abruptly in the center of the paper Shiki began to write readily "sponge gourd has bloomed ", and a little below that phrase, he again moved his brush in a breath "choked by phlegm"

I was a little curious what he was going to write next and was watching the paper closely, then at last he wrote "a departed soul", which bit into my heart.

Hekigoto was very touched when Shiki began to write the poem. Shiki was so weak, and desperately coughing, but he still had a determination to write these haiku.

The three death haiku poems by Shiki written by his own hand about 13 to 14 hours before his death which occurred around 1 a.m. 19 September 1902.

The one in the centre in the largest letters and in four lines is the first poem he wrote:

糸瓜咲て痰のつまりし佛かな

hechima saite tan no tsumarishi hotoke kanathe gourd flowers bloom,

but look—here lies

a phlegm-stuffed Buddha!sponge gourd has bloomed

choked by phlegm

a departed soulsnake gourd has gone to flower

a Buddha have I turned

choked with phlegmWhen the loofah bloomed

He choked on phlegm

And died.The luffa flowered.

I am a soul

Choked with phlegm.The snake gourd blossoms.

My throat blocked with phlegm,

I am already a Buddha.Dishcloth gourd came into flower

I'm going to die

sticking phlegm in my throatThe sponge gourd has flowered!

Look at the Buddha

Choked with phlegm.The loofah blooms and

I, full of phlegm,

become a Buddha.sponge gourds in bloom

this hotoke*

choked by phlegm

*Hotoke is a word for Buddha. It is also used to refer to a person who has died.

Der Schwammkürbis blüht.

Vom Schleim wird langsam erstickt

ein neuer Buddha.

The second verse was written within the small space to the left of the first:

痰一斗糸瓜の水も間にあはず

tan itto hechima no mizu mo ma ni awazua quart of phlegm—

even gourd water

couldn't mop it upgallons of phlegm

even the gourd water

couldn't clear it upa barrel of phlegm

snake gourd water is

just not enoughNo matter how I get the water of dishcloth gourd

It's not enough to clear a large quantity of phlegm

amount to about 12 litergallons of phlegm

too late

even for sponge gourd juiceA barrelful of phlegm—

even loofah water

will not avail me now.Ein Klumpen Auswurf.

Der Saft des Schwammkürbises

konnte nicht helfen.

The third and last poem is on the right hand space and written diagonally:

をととひのへちまの水も取らざりき

ototoi no hechima no mizu mo torazarikithey didn't gather

gourd water

day before yesterday eitherthe gourd water

of the night before yesterday

they didn't get it eithersince the day before yesterday

not even snake gourd water

has been collectedI didn't gather the water of dishcloth gourd

on the day before yesterday (15th Sept. of lunar calendar)

which is good for clearing phlegmthe sponge gourd juice

of two days ago

wasn't even takenLoofah water

from two days ago

left still untouched.Sie ernteten nicht

den Saft des Schwammkürbises,

obwohl Vollmond war.

It is said that fluid taken from a sponge gourd stem is effective in relieving coughing. The night before there was a full-moon The fluid collected on a full moon night was believed to be the best to clear phlegm up. Since Shiki was really dying, Shiki's family may have been too discouraged to collect fluid on the full-moon night. One of his friends described that Shiki looked like a living mummy. On the next day of his 35th birthday he fell into a coma and then on the 19th his life came to end, while sponge gourd blossoms were in bloom in his garden. We call the anniversary of Shiki's death "anniversary of sponge gourd.

Kimiyo Tanaka

-------------------------------------------

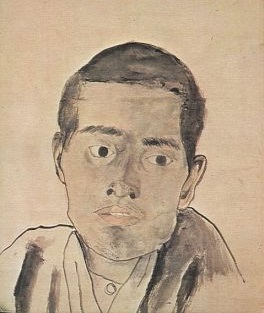

Self-portrait painted by Shiki in water colors in 1900The Japanese haiku poet Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902) died of tuberculosis at thirty-five. In his final days he suffered unbearable pain caused by spinal decay. He couldn't even shift in his bed. About three months before his death, he wrote in an essay for a newspaper: “Until now, I have misunderstood satori in Zen. I mistakenly thought that satori was to die with peace of mind in any condition. Satori is to live with peace of mind in any condition.”

In A Sixfoot Sickbed for June 2, 1902, he wrote, Until now I had mistaken the “Enlightenment” of Zen: I was wrong to think it meant being able to die serenely under any conditions. It means beign able to live serenely under any conditions. (XI, 261)

[Masaoka Shiki: His Life and Works by Janine Beichman, p. 129.]In spite of ill health, Shiki maintained a prominent position in the literary world, and his views on poetry and aesthetics, as well as his own poems, appeared regularly in print. Masaoka frequently mentioned his illness in his poems and in such essays as “Byōshō rokushaku” (1902; “The Six-foot Sickbed”), but maintained an emotional detachment from his physical suffering. During the last years of his life, Masaoka was a bed-ridden invalid, but his home became a meeting place for his friends and followers, who gathered there to discuss literature. Masaoka Shiki died in Tokyo on September 9, 1902, a few weeks before his thirty-fifth birthday.

“Until now, I had misunderstood the Satori, enlightenment of Zen Buddhism. I had thought that satori is to die without fear anytime. But it is a wrong guess. The satori is to live unconcernedly anytime.”One of his infrequent references to Zen is found in the June 2, 1902, entry in Byōshō rokushaku:

“Up to now I have always misunderstood the satori of Zen. I mistakenly supposed that satori was a way to dying tranquilly, regardless of the circumstances, but satori is actually how to live tranquilly, regardless of the circumstances.” In Shiki zenshū 11:261.

[The Winter Sun Shines in: A Life of Masaoka Shiki by Donald Keene]-------------------------------------------

The Poetry of Shiki

On how to sing

the frog school and the skylark school

are arguing.

A

spring day

A long line of footprints

On the sandy beach.

Double

cherry blossoms

Flutter in the wind

One petal after another.

At the gate

Under the oak the shoots

So luxuriant.

Oppressive

heat --

My whirling mind

Listens to the peals of thunder.

The

wild geese take flight

Low along the railroad tracks

In the moonlight

night

-------------------------------------------

I

can see the stones

On the bottom fluctuate

Through the clear water.

Frozen

in the ice

A maple leaf.

Shitting

in the winter turnip field

The distant lights of the city.

-------------------------------------------

the

pear blossoming...

after the battle this

ruined house

------------------------------------------

rowing through

out of the mist

the wide sea

------------------------------------------

Shiki's portrait photo, December 24, 1897

Selected Poems of Masaoka Shiki, Translated by Janine Beichman

quote from the University of Virginia

Source: http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/japanese/shiki/beichman/BeiShik.utf8.htm

Poem numbers are not native to the original source but were derived from the page number and position of each poem in the Beichman edition.

For example, 50.2 refers to the second poem on page

50.16.1

水無月の虚空に涼し時鳥

minazuki no kokū ni suzushi hototogisu

In the coolness

of the empty sixth-month sky...

the cuckoo's cry.

48.1

木をつみて夜の明やすき小窓かな

ki o tsumite yo no akeyasuki komado kana

the tree cut,

dawn breaks early

at my little window

49.1

一重づゝ一重つゝ散れ八重櫻

hitoezutsu hitoezutsu chire yaezakura

scatter layer

by layer, eight-layered

cherry blossoms!

49.2

名月の出るやゆらめく花薄

meigetsu no deru ya yurameku hanasusuki

at the full moon's

rising, the silver-plumed

reeds tremble

50.1

ちる花にもつるゝ鳥の翼かな

chiru hana ni motsururu tori no tsubasa kana

entangled with

the scattering cherry blossoms—

the wings of birds!

50.2

麥蒔やたばねあげたる桑の枝

mugi maki ya tabane agetaru kuwa no eda

wheat sowing—

the mulberry trees

lift bunched branches

50.3

松杉や枯野の中の不動堂

matsu sugi ya kareno no naka no Fudōdō

pine and cypress:

in a withered field,

a shrine to Fudō

51.1

すゝしさや神と佛の隣同士

suzushisa ya kami to hotoke no tonaridoshi

in the coolness

gods and Buddhas

dwell as neighbors

51.2

御佛に尻むけ居れば月涼し

mihotoke ni shirimuke oreba tsuki suzushi

I turn my back

on Buddha and face

the cool moon

51.3

見下せば月にすゞしや四千軒

mioroseba tsuki ni suzushi ya yonsenken

looking down I see,

cool in the moonlight,

4000 houses

52.1

月涼し蛙の聲のわきあがる

tsuki suzushi kawazu no koe no wakiagaru

the moon is cool—

frogs' croaking

wells up

52.2

すゞしさや瀧ほとばしる家のあひ

suzushisa ya taki hotobashiru ie no ai

coolness—

a mountain stream splashes out

between houses

52.3

春風に尾をひろげたる孔雀かな

harukaze ni o o hirogetaru kujaku kana

fanning out its tail

in the spring breeze,

see—a peacock!

53.1

柿くへば鐘が鳴るなり法隆寺

kaki kueba kane ga narunari Hōryūji

I bite into a persimmon

and a bell resounds—

Hōryūji

57.1

稻の花道灌山の日和かな

ine no hana Dōkanyama no hiyori kana

rice flowers—

fair weather on

Dōkanyama

57.2

稻刈るや燒場の烟たゝぬ日に

ine karu ya yakiba no kemuri tatanu hi ni

rice reaping—

no smoke rising from

the cremation ground today

63.1

古庭や月に湯婆の湯をこぼす

furuniwa ya tsuki ni tanpo no yu o kobosu

old garden—she empties

a hot-water bottle

under the moon

64.1 -

庭前

鷄頭の十四五本もありぬべし

"teizen"

keitō no jūshigohon mo arinubeshi

"Before the Garden"

cockscombs...

must be 14,

or 15

65.1

いくたびも雪の深さを尋ねけり

ikutabi mo yuki no fukasa o tazunekeri

again and again

I ask how high

the snow is

65.2

雪ふるよ障子の穴を見てあれば

yuki furu yo shōji no ana o mite areba

snow's falling!

I see it through a hole

in the shutter...

66.1

雪の家に寢て居ると思ふばかりにて

yuki no ie ni nete iru to omou bakari ni te

all I can think of

is being sick in bed

and snowbound...

66.2

障子明けよ上野の雪を一目見ん

shōji ake yo Ueno no yuki o hitome min

open the shutter!

I'll just have a look

at Ueno's snow!

69.1

春雨や傘さして見る繪草紙屋

harusame ya kasa sashite miru ezōshiya

spring rain:

browsing under an umbrella

at the picture-book store

69.2

榎の實散る此頃うとし鄰の子

e no mi chiru konogoro utoshi tonari no ko

the nettle nuts are falling...

the little girls next door

don't visit me these days

70.1

しぐるゝや蒟蒻冷えて臍の上

shigururu ya konnyaku hiete heso no ue

it's drizzling...

devil's tongue, cold on

my belly button

70.2

鬚剃るや上野の鐘の霞む日に

hige soru ya Ueno no kane no kasumu hi ni

getting a shave!

on a day when Ueno's bell

is blurred by haze...

71.1

臥病十年

首あげて折々見るや庭の萩

"Gabyō Jūnen"

kubi agete oriori miru ya niwa no hagi

"Sick in Bed Ten Years"

lifting my head,

I look now and then—

the garden clover

72.1

餘命いくばくかある夜短し

yomei ikubaku ka aru yo mijikashi

how much longer

is my life?

a brief night...

84.2

楊貴妃の寐起顏なる牡丹哉

Yōkihi no neokigao naru botan kana

the peony seems

to think itself Yōkihi

as she awakes

97.1

藤の花長うして雨ふらんとす

fuji no hana nagōshite ame furan to su

wisteria plumes

sweep the earth, and soon

the rains will fall

97.2

黒きまでに紫深き葡萄かな

kuroki made ni murasaki fukaki budō kana

purple unto

blackness:

grapes!

99.1

病牀の我に露ちる思ひあり

byōshō no ware ni tsuyu chiru omoi ari

I thought I felt

a dewdrop on me

as I lay in bed

100.1

紅梅の散りぬ淋しき枕元

kōbai no chirinu sabishiki makura moto

crimson plum blossoms

scattered over the loneliness

of the bed...

100.2

紅梅の落花をつまむ疊哉

kōbai no rakka o tsumamu tatami kana

fallen petals of

the crimson plum I pluck

from the tatami

102.2

絲瓜咲て痰のつまりし佛かな

hechima saite tan no tsumarishi hotoke kana

the gourd flowers bloom,

but look—here lies

a phlegm-stuffed Buddha!

103.1

痰一斗絲瓜の水も間に合はず

tan itto hechima no mizu mo ma ni awazu

a quart of phlegm—

even gourd water

couldn't mop it up

103.2

をとゝひのへちまの水も取らざりき

ototoi no hechima no mizu mo torazariki

they didn't gather

gourd water

day before yesterday either

113.1

ごて/\と草花植し小庭かな

gotegote to kusabana ueshi koniwa kana

a jumble of

flowers planted—

see, the little garden!

134.1

絲瓜さへ佛になるぞ後るゝな

hechima sae hotoke ni naru zo okururu na

hey!—even snake gourds

become Buddhas—

don't get caught behind!

134.2

成佛ヤ夕顏ノ顔ヘチマノ屁

jōbutsu ya yūgao no kao hechima no he

Buddha-death:

the moonflower's face,

the snake gourd's fart

136.1

病牀の財布も秋の錦かな

byōshō no saifu mo aki no nishiki kana

the wallet

by the bed is my

autumn brocade

136.2

栗飯ヤ病人ナガラ大食ヒ

kurimeshi ya byōnin nagara ōkurai

chestnut rice—

though a sick man,

still a glutton

136.3

カブリツク熟柿ヤ髯ヲ汚シケリ

kaburitsuku jukushi ya hige o yogoshikeri

I sink my teeth

into a ripe persimmon—

it dribbles down my beard

136.4

驚くや夕顏落ちし夜半の音

odoroku ya yūgao ochishi yowa no oto

surprise!

a moonflower fell—

midnight sound

-------------------------------------------

http://members.aol.com/markabird/shiki.html

The desolation of winter;

passing through a small hamlet,

a dog barks.

Evening

snow falling,

a pair of mandarin ducks

on an ancient lake.

Now

and again

it turns to hail;

the wind is strong.

With

a bull on board,

the ferry boat,

through the winter rain.

A

stray cat

excreting

in the winter garden.

Only

the gate

of the abbey is left,

on the winter moor.

------------------------------------------

柿くへば鐘が鳴るなり法隆寺

kaki kueba kane ga naru nari hōryūji

biting into a persimmon

a bell resounds

Hōryū-ji

いくたびも雪の深さを尋ねけり

ikutabi mo yuki no fukasa o tazune keri

again and again

I asked the depth

of the snow

雪ふりや棟の白猫聲はかり

yukifuri ya mune no shironeko koe bakari

snow –

white cat on the roof ridge

just its voice

雑煮くふてよき初 夢を忘れけり

zōni kūte yoki hatsuyume o wasure keri

having eaten zōni

I forgot my good dream

of the New Year

春や昔十五万石の城下哉

haru ya mukashi jūgoman goku no jōka kana

grand castle town

of the past ―

spring

十年の汗を道後の温泉に洗へ

jūnen no ase o dōgo no yu ni arae

wash away

those 10 years of sweat

Dōgo hot spring

夏草やベースボールの人遠し

natsukusa ya bēsu bōru no hito tōshi

summer grass

the baseball players

so far away

桔梗活けてしばらく仮の書斎かな

kikyō ikete shibaraku kari no shosai kana

arranging bellflowers

this will be my study

for the time being

putting bellflowers in a vase

this is my study

for the time being

-------------------------------------------

aiming

at

deutzia blossoms

little cuckoo

spring

breeze

show off the castle

above the pine tree

-------------------------------------------

By

the ruined mansion,

Fowls roaming

Among the hibiscus

The

dead body

Of a trodden-on crab,

This autumn morning

Fallen

leaves

Come flying from elsewhere:

Autumn is ending.

Having

felled

A pasania tree,-

the sky of autumn.

-------------------------------------------

I

want to sleep

Swat the flies

Softly, please.

After

killing

a spider, how lonely I feel

in the cold of night!

For

love and for hate

I swat a fly and offer it

to an ant.

A

mountain village

under the pilled-up snow

the sound of water.

Night;

and once again,

the while I wait for you, cold wind

turns into rain.

The

summer river:

although there is a bridge, my horse

goes through the water.

A

lightning flash:

between the forest trees

I have seen water.

-------------------------------------------

Shiki Masaoka appeared in the haiku world as the critic to Basho Matsuo. Shiki criticized Basho's famous haikus in his criticism "Basho Zatsudan" (Miscellanies about Basho). He didn't deny Basho's all works, but he reproached his hokkus for lack of poetic purity and for having explanatory prosaic elements.

On the other hand, he extolled Buson Yosa who had been unrecognized yet. He thought that Buson's haikus are technically refined and they transmit efficiently clear impressions to readers.

After the discovery of the Western philosophy, Shiki convinced that laconic descriptions of things were effective for literary and pictorial expression. He insisted on the importance of "shasei" (写生 sketching). This idea led his haikus to the visual description and to the concise style.

The haiku innovation by Shiki created a great sensation in the whole of Japan and revived the languishing haiku world.

あたたかな雨が降るなり枯葎

The

tepid rain falls

On the bare thorn.

氷解けて古藻に動く小海老かな

Thawed out pond.

A shrimp moves

Among old algae.

大砲のどろどろと鳴る木の芽かな

The cannon rolls its rumble.

Leaf buds of a tree.

涼しさや松這ひ上る雨の蟹

How cool it is!

A small crab, in the rain,

Climbs on a pine.

蓮池の浮葉水こす五月雨

Lotus leaves in the pond

Ride on water.

Rain in June.

汽車過ぎて烟うづまく若葉かな

Smoke whirls

After the passage of a train.

Young foliage.

半日の嵐に折るる葵かな

The storm

During half-day

Has broken the stem of mallow.

月も見えず大きな波の立つことよ

We cannot see even the moon.

And rise big waves.

蔦さがる岩の凹みや堂一つ

Above a hollow of rock

An ivy hangs.

One small temple.

Shiki denied

the value of haikai-renga and always used the word "haiku" instead of

"haikai" or "hokku". Today, haikai-renga is called "renku",

but few specialists are interested in this poetic form.

-------------------------------------------

Shiki's photo (then

31-year-old)

Shiki's haiku

Tr. by Tanaka Kimiyo

http://www.cc.matsuyama-u.ac.jp/~shiki/kim/shikihaiku.html

http://web.archive.org/web/20161229235830/http://www.cc.matsuyama-u.ac.jp/~shiki/sm/sm.html

Spring

春の霜絲遊となって燃にけり

haru no shimo shiyuu to natte moenikeri

Spring frost

dancing in the air

a shimmer of heat鶏なくや小富士の麓桃の花

torinaku ya kofuji no fumoto momo no hana

a cock crows

at the foot of the small Mt. Fuji

peach blossoms故郷はいとこの多し桃の花

furusato wa itoko no ooshi momo no hana

my hometown

many cousins-

peach blossoms松の根に薄紫の菫かな

matsu no ne ni usumurasaki no sumire kana

at the root

of a pine tree

light lavender violet夕月や一かたまりに散る櫻

yuuzuki ya hitokatamari ni chiru sakura

moon at twilight,

a cluster of petals falling

from the cherry treeいちはつの一輪白し春の暮

ichiihatsu no ichirin shiroshi haru no kure

an iris

whiter at twilight

My hometownふるさとやどちらを見ても山笑ふ

furusato ya dorira o mitemo yama warau

My hometown

wherever I look

mountains laugh with vendure恋しらぬ猫や鶉を取らんとす

koi shiranu neko ya uzura o torantosu

a fancy-free cat

is about to catch

a quail春雨の土塀にとまる烏かな

harusame no dobei ni tomaru karasu kana

perching on a mud wall

in the spring rain

a crow春風や城あらわるゝ松の上

harukaze ya shiro arawaruru matsu no ue

spring breeze

show off the castle

above the pine tree春 の 山重なりあふて皆丸し

haru no yama kasanarioute mina marushi

Mountains in spring

overlapping each other

all round生壁に花吹きつけて春の風

namakabe ni hana fukitsukeru haru no kaze

cherry blossom petals

blown by the spring breeze

against the undried wallつゝじ咲く絶壁の凹み佛立つ

tsutsuji saku zeppeki no kubomi hotoke tatsu

blooming azaleas

in a hollow on a cliff

a Buddha stands

Summer

卯の花をめかけてきたかほとゝぎす

unohana o megakete kitaka hototogisu

aiming at

deutzia blossoms

little cuckoo山々は萌黄浅黄やほと々ぎす

yamayama wa moegi asagi ya hototogisu

Mountains are

yellow green, pale yellow-

a cuckoo cries城山の浮かみ上がるや青嵐

shiroyama no ukami agaru ya aoarashi

castle hill

high above

breezy green門さきにうつむきあふや百合の花

kadosaki ni utsumukiau ya yuri no hana

at the front gate

dropping their heads

lilies blooming草茂みベースボールの道白し

kusa shigemi besuboru no michi shiroshi

through a growth of weeds

runs an open path

baseball diamond五女ありて後の男や初幟

gojo arite nochi no otoko ya hatsunobori

It's a boy

after five daughters

carp streamers二筋に虹の立ったる青田哉

futasuji ni niji no tattaru aota kana

two rainbows

have risen over

the green paddy field静かさに蛍飛ぶなり淵の上

shizukasa ni hotaru tobunari fuchi no ue

stillness - -

fireflies are glowing over

deep water夏嵐机上の白紙飛びつくす

natsuarashi kijo no hakushi tobitsukusu

summer storm

white paper on the desk

all flies awayIn Japan summer storm can be described as a green wind,

because all trees in summer are full of green leaves.

In this haiku, the color contrast of green and white paper

gives a very sharp and clear and refreshing feeling.君を送りて思ふことあり蚊帳に泣く

kimi o okurite omou koto ari kaya ni naku

leaving me

something on my chest

tears on my mosquito net余命いくばくかある夜短し

yomei ikubaku ka aru yoru mijikashi

my remaining days

are numbered

a brief night薔薇を剪る鋏刀の音や五月晴

bara o kiru hasami no oto ya satsukibare

pruning a rose

sound of the scissors

on a bright May day赤薔薇や萌黄の蜘蛛の這ふて居る

akabara ya moegi no kumo no hohteiru

a yellow green spider

crawling on

a red rose蝸牛や雨雲さそふ角のさき

dedemushi ya amagumo sasou tsuno no saki

a snail

luring rain clouds

with feeler tipsふるさとや親すこやかに鮓の味

furusato ya oya sukoyakani sushi no aji

my hometown

parents are well

taste of sushi世の中の重荷おろして昼寝かな

yononaka no omoni oroshite hirune kana

relieved of a burden

in the everyday life

an afternoon nap伸び切って夏至に逢ふたる葵かな

nobikitte geshi ni ohtaru aoi kana

a hollyhock

shot up to meet

the summer solstice夏山や萬象青く橋赤し

natsuyama ya bansho aoku hashi akashi

summer mountain

all creatures are green

a red bridge鳴きやめて飛ぶ時蝉の身ゆるなり

nakiyamete tobutoki semi no miyuru nari

The singing stopped

a flying cicada

I saw it!淋しさや花火のあとの星の飛ぶ

sabishisa ya hanabi no ato no hoshi no tobu

loneliness

after the fireworks

stars' shooting夕風や白薔薇の花皆動く

yukaze ya shirobara no hana mina ugoku

an evening breeze

white rose petals are

all ruggled一匙のアイスクリムや蘇る

hitosaji no aisukurimu ya yomigaeru

one spoonful

of ice cream brings me

back to life蓼噛んでひとりこらえる思ひ哉

tade kande hitori koraeru omoikana

biting into a bitter weed

alone I bear

my feelings十年の汗を道後の温泉に洗へ

junen no ase o DOGO no yu ni arae

ten year's sweat

washed away

back at Dogo Onsen暮れきらぬ白帆に白き夏の月

kurekiranu shiraho ni shiroshi natsu no tsuki

at nightfall

a summer moon, white --

on the white sail紫陽花の雨に浅黄に月に青し

ajisai no ame ni asagi ni tsuki ni aoshi

hydrangeas

pale blue in the rain

blue in the moonlight紫陽花や壁のくづれをしぶく雨

ajisai ya kabe no kuzure o shibuku ame

hydrangeas ---

rain splashing upon

the crumbling walls古池やさかさに浮かふ蝉のから

furuike ya sakasa ni ukabu semi no kara

an old pond-

floating upside down

a cicada's shell

Autumn

低く飛ぶ畦のいなごや日の弱り

hikuku tobu aze no inago ya hi no yowari

Locusts fly low

over the levee

in the fading sunshine秋風や生きて会ひ見る汝れと我

akikaze ya ikite aimiru nare to ware

Autumn wind -

met, returning alive

you and me松山や秋より高き天守閣

Matsuyama ya akiyori takaki tenshukaku

Matsuyama castle

the keep is higher than

the autumn sky雲走り雲追ふ二百十日かな

kumo hashiri kumo ou nihyakutoka kana

clouds're running past

running after clouds

the Storm Day秋風や生きてあひ見る汝れと我

akikaze ya ikite aimiru nare to ware

autumn wind -

met, returning alive

you and me行く秋や手を引き合ひし松二木

yukuaki ya te o hikiaishi matsu futaki

autumn is leaving

tugging each others' branches

two pine trees野分の夜書読む心定まらず

nowaki no yo fumi yomu kokoro sadamarazu

on a stormy night

while reading a letter

wavering mind黒きまでに紫深き葡萄かな

kuroki madeni murasaki fukashi budo kana

almost black

deepening purple

ripe grapes行く秋の我に神無し仏なし

yukuaki no ware ni kami nashi hotoke nashi

with advancing autumn

I am without gods

without Buddha行く我にとヾまる汝に秋二つ

yuku ware ni todomaru nare ni aki futatsu

I am going

you're staying

two autumns for us身の上や御籤をひけば秋の風

minoue ya mikuji o hikeba aki no kaze

my fate,

a fortune tells

- autumn wind梨むくや甘き雫の刃を垂るゝ

nashimuku ya amaki shizuku no ha o taruru

peeling a pear

sweet drops dripping

along the knife edge故郷や祭りも過ぎて柿の味

furusato ya matsuri mo sugite kaki no aji

hometown -

festivals are over

flavorful persimmonsともし火の見えて紅葉の奥深し

tomoshibi no miete momiji no oku fukashi

lights

far way, through

leaves of dense autumnal tints名月に思ふことあり我一人

meigetsu ni omoukoto ari warehitori

the bright moon

something in my breast

I am alone名月に飛び行く雲の行方かな

meigetsu ni tobiyuku kumo no yukue kana

the bright moon

I wonder where the clouds

are flying off to引き裂いた雲のあとなり秋の風

hikisaita kumo no atonari aki no kaze

following

clouds torn apart

autumn wind朝寒や紫の雲消えて行く

asasamu ya murasaki no kumo kieteyuku

morning coolness

purple clouds are

vanishing山城に残る夕日や稲の花

yamashiro ni nokoru yuhi ya ine no hana

the setting sun

remains on the mountain

castle flowering rice雲はあれど彼岸の入り日赤かりし

kumo wa aredo higan no irihi akakarishi

crimson sunset

even through clouds

vernal equinox三千の俳句を閲し柿二つ

sanzen no haiku o kemishi kaki futatsu

looking through

three thousand haiku eating

two persimmons鐘の音の輪をなして来る夜長かな

kane no ne no wa o nashite kuru yonaga kana

sounds of a temple bell

reverberate in a circle

a long night犬の声靴の音ながき夜なりにけり

inu no koe kutsu no ne nagakiyo narini keri

a dog howling

sound of footsteps

longer nights

Winter and New Year's

二つ三つ石ころげたる枯野かな

futatsu mitsu ishi korogetaru kareno kana

two or three rocks

strewn about

dried up field寒椿黒き佛に手向けばや

kantsubaki furuki hotoke ni tamukabaya

winter camellia

I wish I could offer it

to the sooty Buddha松山の城を見おろす寒さかな

Matsuyama no shiro o miorosu samusa kana

coldness

looking down from above

Matsuyama Castle薪をわるいもうと一人冬籠

maki o waru imouto hitori fuyugomori

splitting wood

my sister alone -

wintering冬木立のうしろに赤き入り日かな

fuyukodachi no ushiro ni akaki irihikana

behind the stand

of winter trees

a red sunset門前のすぐに坂なり冬木立

monnzen no sugu ni saka nari fuyu-kodachi

just outside the gate

the road slopes downward

winter trees寒けれど酒もあり温泉もある処

samukeredo sake mo ari yu mo aru tokoro

It is cold, but

we have sake

and the hot spring* * *

梅提げて新年の御慶申しけり

ume sagete shinnen no gyokei moshikeri

New Year's greetings

with a plum branch

in hand空近くあまりまばゆき初日哉

sora chikaku amari mabayuki hatsuhi kana

the sky draws near

such a bright sunrise

New Year's Day元日の人通りとはなりにけり

ganjitsu no hitodori towa narinikeri

New Year's Day

has come -

quiet streets一年は正月に一生は今に在り

ichinen wa shogatsu ni issho wa ima ni ari

The year begins

on New Year's day

our life is Now星消えてあとは五色の初霞

hoshi kiete ato wa goshiki no hatsugasumi

the stars vanished

and then --

five-colored New Year's mist

-------------------------------------------

ちる花に仏とも法ともしらぬ哉

chiru hana ni butsu tomo nori tomo shiranu kana

in scattering blossoms

Buddha and Buddhism

unknown

Facing away from me

Darning old tabi –

My wife.

Devotion to the Great Saint,

the temple of Ishite...

rice plants abloom.

(Alas my) fortune;

drawing divine lots,

the aurumn wind.

-------------------------------------------

SHIKI (1867-1902)

Translated by Lucien Stryk

- Extracts from CAGE OF FIREFLIES, published by Swallow Press, 1993 -

White butterfly

darting among pinks -

whose spirit?

Indian summer:

dragonfly shadows seldom

brush the window.

Aged nightingale -

how sweet

the cuckoo's cry.

Wicker chair

in pinetree's shade,

forsaken.

Stone

on summer plain -

world's seat.

Summer sky

clear after rain -

ants on parade

Imagine -

the monk took off

before the moon shone.

Thing long forgotten -

pot where a flower blooms,

this spring day

------------------------------------------

Haiku Monuments of Masaoka Shiki

--------------------------------------------------------

References

Addiss, Stephen, Old Taoist - the life, art, and poetry of Kodojin,

Beichman, Janine, Masaoka Shiki, previously published by Twayne Publishers in 1982, first paperback edition, Kodansha International, Tokyo, 1986

Beichman-Yamamoto, Janine, Masaoka Shiki's A Drop of Ink, Monumenta Nipponica XXX, 3, 1965

Blyth, R. H. Haiku, 4 vol., Hokuseido Press, Tokyo 1963-64

Brower, Robert H. , and Miner, Earl, Japanese Court Poetry, Stanford University Press, 1961

Brower, Robert H., Masaoka Shiki and tanka Reform, in Tradition and Modernization in Japanese Culture, ed. Donald H. Shively, Princeton University Press, 1971

Henderson, Harold, An Introduction to Haiku, Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday, 1958

Higginson, William J., with Penny Harter, The Haiku Handbook - How to Write, Share, and Teach Haiku, Kodansha International, 1985

Isaacson, Harold J. trans. & ed., Peonies Kana - Haiku by the Upasaka Shiki, George Allen & Unwin Ltd., London, First ed., 1973 (It was published by Theatre Arts Books, New York, 1972)

Keene, Donald, Shiki and Takuboku, in Landscapes and Portraits: Appreciations of Japanese Culture, Tokyo and Palo Alto, Kodansha International Ltd 1971

Keene, Donald, Dawn to the West - A History of Japanese Literature, vol. 4, Columbia University Press, New York, First published 1984

Kimata, Osamu, Shiki Masaoka: His Haiku and Tanka, Philosophical Studies of Japan, VIII, 1967, (compiled by Japanese National Commission for UNESCO and published by Nippon Gakujutsu Shinkokai)

Miner, Earl, The verse record of My Peonies, in Japanese Poetic Diaries, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1969

Morris, Mark,"Buson and Shiki: Part One." Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 44, no. 2 (December 1984); "Buson and Shiki: Part Two." Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 45, no. 1 (June 1985)

Nippon Gakujutsu Shinkokai, Special Haiku Committee of Japanese Classics Translation Committee consisting of Aso Isoji et al., Haikai and Haiku, Tokyo, Nippon Gakujutsu Shinkokai, 1958

Rexroth, Kenneth, 100 More Poems from the Japanese

Ueda, Makoto, Modern Japanese Haiku: An Anthology, University of Tokyo Press, 1976

Watson, Burton, Masaoka Shiki - Selected Poems, Columbia University Press, 1997

Yasuda, Kenneth, The Japanese Haiku: Its Essential Nature, History and Possibilities in English

Rimer, J. Thomas and Morrell, Robert E., Guide to Japanese Poetry., Boston , G.K. Hall and co., 1975

http://fukiosho.org/archive/reference/International_Haiku_Convention_2000.pdf

http://www.haikuhut.com/JAPANANDTHEWEST:SHIKIANDMODERNISM.pdf

Masaoka Shiki: Making of the Myth of Haiku by YOKOTA-MURAKAMI Takayuki

http://publications.nichibun.ac.jp/region/d/NSH/series/kosh/1996-03-25-2/s001/s035/pdf/article.pdf

J. Keith Vincent, Masaoka Shiki and the Meaning of Illness

http://www.academia.edu/14477579/Masaoka_Shiki_and_the_Meaning_of_Illness

Masaoka Tsunenori — the Haiku Master Shiki

by Janice M Bostok

https://australianhaikusociety.org/2007/04/25/masaoka-tsunenori-the-haiku-master-shiki-2/

Analysis of the medical care of Masaoka Shiki, as seen in "Gyoga Manroku"

by

Nobuko SEKINAGA

http://ci.nii.ac.jp/els/110010059515.pdf?id=ART0010629034&type=pdf&lang=en&host=cinii&order_no=&ppv_type=&lang_sw=&no=1494104059&cp=

--------------------------------------------------------

128 haikus de Masaoka Shiki

Haikus de primavera

http://traducirjapon.blogspot.hu/2009/05/haikus-de-primavera_09.html

Trad. de Alberto Silva

元旦は是も非もなくて衆生なり

Gantan wa ze mo hi mo nakute shujō nari

El año se inaugura

¿Todos buenos?

¿Todos malos?

Todos seres humanos

女負ふて川渡りけり朧月

Onna ōte kawa watari keri oborozuki

A lomos de aquel hombre

la chica cruza el río,

bajo luces rasgadas

de luna

牛部屋の牛のうなりや朧月

Ushibeya no ushi no unari ya oborozuki

Muge la vaca

en el establo. Mientras, la luna

se echa un velo

あたゝかに白壁ならぶ入江哉

Atataka ni shirakabe narabu irie kana

En la ensenada,

filas de casas tibias,

paredes blancas

川に沿うて行けど橋なし日の永き

Kawa ni sōte yukedo hashi nashi hi no nagaki

Corriente abajo,

sin huella de algún puente

para este día

que no se acaba

汽車道にならんでありく日永哉

Kishamichi ni narande ariku hinaga kana

En fila india,

larga, marcha la jornada

sobre los rieles

百人の人夫土掘る日永哉

Hyakunin no ninpu tsuchi horu hinaga kana

Cava que te cava:

la fila de braceros

se alarga más que el día

舟と岸と話してゐる日永かな

Fune to kishi to hanashi shite iru hinaga kana

¡Largo día!

Una lancha conversa

con la orilla

大仏のうつらうつらと春日哉

Daibutsu no utsura-utsura to haruhi kana

El Gran Buda

se echa sus siestas

primaverales

砂浜に足跡長き春日かな

Sunahama ni ashiato nagaki haruhi kana

Largas huellas de pasos

en la playa de aquel largo

día templado

かへり見れば行きあひし人の霞みけり

Kaerimireba yukiaishi hito no kasumi keri

Fue darme vuelta

y el hombre que cruzaba

se hizo niebla

春雨や傘さして見る絵草紙屋

Harusame ya kasa sashite miru ezōshiya

Apenas llueve

Bajo el paragua, unos libros

(hago que leo)

陽炎や三千軒の家のあと

Kagerō ya sanzen-gen no ie no ato

(Presenciando un gran incendio en Tokyo)

Tres mil braseros

soplando aire caliente:

ciudad en llamas

春の野や何に人ゆき人かへる

Haru no no ya nani ni hito yuki hito kaeru

Gentes por el campo

en primavera: ¿adónde van?

¿de dónde vienen?

大仏の片肌の雪解けにけり

Daibutsu no katahada no yuki toke ni keri

Nieve derretida:

le asoma un hombro

a Buda

さゝ波に解けたる池の氷かな

Sasanami ni toketaru ike no kōri kana

Olitas

descascaran

el hielo

de la charca

燈せば雛に影あり一つゞつ

Hitomoseba hina ni kage ari hitotsu-zutsu

Luz en la lumbre

Cada muñeca viste

su propia sombra

名所とも知らで畑うつ男かな

Meisho to mo shirade hata utsu otoko kana

Cava el buen hombre

No sabe

que es un lugar famoso

日一日同じ処に畠打つ

Hi ichi-nichi onaji tokoro ni hatake utsu

Un día entero,

cava que te cava

el mismo agujero

おそろしや石垣崩す猫の恋

Osoroshi ya ishigaki kuzusu neko no koi

Gatos calientes

(¡derriban muros

para poder amarse!)

雲をふみ霞を吸うやあげ雲雀

Kumo wo fumi kasumi wo sū ya age hibari

Roza las nubes

la alondra. Bebe niebla

(al fin remonta)

雲雀はと蛙はと歌の議論かな

Hibari wa to kaeru wa to uta no giron kana

Rivalidades:

¿el canto de la alondra

mejor que el de la rana?

ぬれ足で雀のありく廊下かな

Nureashi de suzume no ariku rōka kana

El gorrión a saltitos

por el porche

(tiene los pies mojados)

石に寝る蝶薄命の我を夢むらん

Ishi ni neru chō hakumei no ware wo yumemuran

Mariposa que duermes

sobre la piedra,

¿puedes soñar mi vida

corta y desierta?

よく見れば木瓜の莟や草の中

Yoku mireba boke no tsubomi ya kusa no naka

Puesto a mirar,

veo un capullo entre la hierba,

de magnolio

紫の夕山つじゝ家もなし

Murasaki no yūyama tsutsuji ie mo nashi

Las azaleas

entintan las montañas

abandonadas

del ocaso

柳あり舟待つ牛の二三匹

Yanagi ari fune matsu ushi no nisan-biki

Junto al sauce:

dos, tres vacas esperan

el servicio de balsa

舟と岸柳へだつる別れ哉

Fune to kishi yanagi hedatsuru wakare kana

Dos se despiden:

un sauce se entromete

entre el bote y la orilla

街中を小川流るる柳かな

Machinaka wo ogawa nagaruru yanagi kana

Por el poblado,

serpentea un arroyo

(igual los sauces)

菜の花や金蓮光る門徒寺

Nanohana ya kinren hikaru montodera

Flores de colza

Flores de berro

Ornato de los templos

カナリヤは逃げて春の日暮れにけり

Kanariya wa nigete haru no hi kure ni keri

Se escapó el canario,

como se esfuma un día más

de primavera

長閑さの独り行き独り面白き

Nodokasa no hitori yuki hitori omoshiroki

Calma

Solo vagabundear

Solo disfrutar

Haikus de verano

http://traducirjapon.blogspot.hu/2009/05/haikus-de-verano.html

Trad. de Alberto Silva

六月の海見ゆるなり寺の像

Roku-gatsu no umi miyuru nari tera no zō

El Buda del templo

apenas divisa

las olas lejanas de junio

短夜の灯火のこる港かな

Mijikayo no tomoshibi nokoru minato kana

La noche ya se muere

Quedan poquitas luces

en el puerto

余命いくばくかある夜短し

Waga inochi ikubaku ka aru yo mijikashi

La vida mía

La noche entera

¿Cuánta me queda todavía?

¡Tan pasajera!

涼しさや青田の中に一つ松

Suzushisa ya aota no naka ni hitotsu matsu

En un verde arrozal

la frescura

de aquel único pino

涼しさや石燈籠の穴の海

Suzushisa ya ishidōrō no ana no umi

¡Cómo refresca!: el mar

(lo miro por los huecos

de ese farol de piedra)

島あれば松あり風の音涼し

Shima areba matsu ari kaze no oto suzushi

Si hay isla, hay pino

Si hay pino, hay fresco

rumor de viento

大仏に腸のなき涼しさよ

Daibutsu ni harawata no naki suzushisa yo

Gran Buda

(de una frescura

sin entrañas)

暑くるし乱れ心や雷をきく

Atsukurushi midaregokoro ya rai wo kiku

Calor de infierno

Da vueltas mi cabeza

Restalla el trueno

鍬立ててあたり人なき暑さ哉

Kuwa tatete atari hito naki atsusa kana

La azada espera

Nadie a la vista

Sólo solana

海士が家に干魚の匂ふ暑さかな

Amagaya ni hizakana no niou atsusa kana

Casa de un pescador:

huele a pescado seco

y a calor

男ばかりの中に女の暑さかな

Otoko bakari no naka ni onna no atsusa kana

Presencia

de una mujer entre esos hombres:

¡qué calor!

帆の大き阿蘭陀船や雲の峰

Ho no ōki oranda-bune ya kumo no mine

El barco de gran vela

holandés coronado

de nubes se aleja

夏嵐机上の白紙飛び盡す

Natsuarashi kijō no hakushi tobi tsukusu

Vendaval de verano

Mis papeles se asustan

(salen volando)

一人居る編輯局や五月雨

Hitori iru henshūkyoku ya satsukiame

Solo en el diario

y afuera

llueve en mayo

夕立にうたるゝ鯉のあたまかな

Yūdachi ni utaruru koi no atama kana

Las gotas del chubasco

¡picotean la trompa

de las carpas!

炎天に菊を養ふあるじかな

Enten ni kiku wo yashinau aruji kana

Bajo un sol de justicia,

el amo que cultiva

crisantemos

夏川や馬つなぎたる橋柱

Natsukawa ya uma tsunagitaru hashi bashira

Caballo atado

del soporte del puente

del campo

del verano

夏川や橋あれど馬水を行く

Natsukawa ya hashi aredo uma mizu wo yuku

Un puente lo cruza,

pero al flete le gusta

vadearlo, a ese río,

en verano

金持も熊も来てのむ清水哉

Kanemochi mo kuma mo kite nomu shimizu kana

Igual que hacen los osos,

se sirven del manantial

los millonarios

大風の俄かに起る幟かな

Ōkaze no niwaka ni okoru nobori kana

Un fuerte viento

despertó de repente

la bandera de la fiesta

de los niños

人もなし子一人寝たる蚊帳の中

Hito mo nashi ko hitori netaru kaya no naka

Nadie a la vista

Salvo un bebé que duerme

en el mosquitero

二階から屋根船まねく團扇かな

Nikai kara yanebune maneku uchiwa kana

Con su abanico:

desde el primer piso

llama al barco

ふわふわとなき魂こゝに来て涼め

Fuwa-fuwa to naki tama koko ni kite suzume

Vengan a refrescarse,

espíritus flotantes,

sin pensárselo tanto

錦着て牛の汗かく祭りかな

Nishiki kite ushi no ase kaku matsuri kana

Un toro engalanado

suda y se limita

a observar la fiesta

蝙蝠の飛ぶ音暗し藪の中

Kōmori no tobu oto kurashi yabu no naka

Entre malezas

se oyen sones sombríos

(vuelan murciélagos)

説教に穢れた耳を不如帰

Sekkyō ni kegareta mimi wo hototogisu

El cuco canta, pero entona

para oídos ahítos

de sermones

雷晴れて一樹の夕日蝉の声

Rai harete ichiju no yūhi semi no koe

Escampa: lo anuncia

la cigarra colgada

de una rama en ocaso

空家の門に蝉なく夕日かな

Akiie no mon ni semi naku yūhi kana

En el porche vacío,

la cigarra se enrosca

con los últimos rayos

de sol

手の内に螢つめたき光かな

Te no uchi ni hotaru tsumetaki hikari kana

Destellos de cocuyo

me enfrían la palma

de la mano

生きた眼をつつきに来るか蠅の飛ぶ

Ikita me wo tsutsuki ni kuru ka hae no tobu

Sigo vivo y me siguen

picando en los ojos (las moscas

que vuelan)

夏木立入りにし人の跡もなし

Natsu kodachi irinishi hito no ato mo nashi

No quedan huellas

de aquel que entró en el bosque

siendo verano

鐘もなき鐘つき堂の若葉かな

Kane mo naki kanetsukidō no wakaba kana

Lleno de tiernas ramas:

campanario

sin campana

夕風や白薔薇の花皆動く

Yūkaze ya shirobara no hana mina ugoku

Brisa en la tarde

sobre unas rosas blancas

que se estremecen

蓮の花さくやさびしき停車場

Hasu no hana sakuya sabishiki teishajō

En el andén

del tren, tan solitario,

unos lotos floridos

夕顔に都なまりの女かな

Yūgao ni miyako namari no onna kana

¡Flores de luna!

anuncia aquella chica

con acento de Kyoto

Haikus de otoño

http://traducirjapon.blogspot.hu/2009/05/haikus-de-otono.html

Trad. de Alberto Silva

草花を画く日課や秋に入る

Kusabana wo egaku nikka ya aki ni iru

Se abre el otoño

Cada día un trabajo:

¡pintar las flores!

朝寒や小僧ほがらかに経を読む

Asasamu ya kozō hogarakani kyō wo yomu

Mañana fría:

alegres oraciones

canta el novicio

秋晴れてものゝ煙の空に入る

Aki harete mono no kemuri no sora ni iru

Espléndido día en que el humo

se eleva en otoño

hasta el cielo

ふみつけた蟹の死骸やけさの秋

Fumitsuketa kani no shigai ya kesa no aki

Cadáver de un cangrejo

aplastado, mañana

en otoño

病人に八十五度の残暑かな

Byōnin ni hachijūgo-do no zansho kana

“Cuarenta grados”:

en su fiebre, el enfermo

sigue en verano

山門をぎいと鎖すや秋の暮

Sanmon wo gii to tozasu ya aki no kure

Arrastro la puerta del templo

Hace cric (otoñal

el sol se va poniendo)

長き夜を月取る猿の思案哉

Nagaki yo wo tsuki toru saru no shian kana

Horas largas, nocturnas

Y un mono que planea

echar mano a la luna

長き夜や千年の後を考へる

Nagaki yo ya chitose no nochi wo kangaeru

La noche no se acaba

“¿Qué vendrá –fantaseo-

en mil años más?”

大寺のともし少き夜寒かな

Ōdera no tomoshi sukunaki yosamu kana

Hay pocas luces

o demasiado templo

¡qué noche más fría!

次の間の灯も消えて夜寒哉

Tsugi no ma no tomoshi mo kiete yosamu kana

También se apaga

la luz de al lado (la noche

parece más helada)

須磨寺の門を過ぎ行く夜寒哉

Suma-dera no mon wo sugiyuku yosamu kana

Por afuera

del templo de Suma

paso de noche

(pasa el frío)

蜘殺すあとの淋しき夜寒哉

Kumo korosu ato no sabishiki yosamu kana

Muerta la araña,

la noche se hace glacial

¡y solitaria!

牧師一人信者四五人の夜寒かな

Bokushi hitori shinja shigo-nin no yosamu kana

Un cura

Cuatro fieles

Una noche glacial

木に椅れば枝葉まばらに星月夜

Ki ni yoreba edaha mabara ni hoshizukiyo

Veo estrellarse la noche,

recostado en un árbol

de pocas ramas

y menor follaje

秋風や生きてあひ見る汝と我

Akikaze ya ikite aimiru nare to ware

Viento de otoño

Vivimos, nos miramos,

tú y yo

馬下りて川の名問へば秋の風

Uma orite kawa no na toeba aki no kaze

Me bajo del caballo

“¿Cómo se llama el río?”

Viento de otoño

馬の尾に佛性ありや秋の風

Uma no o ni busshō ari ya aki no kaze

¿La cola del potro

contiene sustancia divina?

(el viento es de otoño)

秋風や我に神なし佛なし

Akikaze ya ware ni kami nashi hotoke nashi

El viento del otoño

no deja budas vivos,

no deja dioses

心細く野分のつのる日暮かな

Kokorobosoku nowaki no tsunoru higure kana

Oscurece

La tormenta se afianza

Mi miedo crece

白露に家四五軒の小村哉

Shiratsuyu ni ie shigo-ken no komura kana

Una aldea:

cuatro o cinco casitas

blanqueadas de rocío

朝露や飯焚く煙草を這ふ

Asatsuyu ya meshi taku kemuri kusa wo hau

Rocío sobre la mañana

y sobre el cesped

vapor de arroz

人にあひて恐しくなりぬ秋の山

Hito ni aite osoroshiku narinu aki no yama

El miedo

de un encuentro

en los montes

de otoño

門を出て十歩に秋の海広し

Mon wo dete ju-ppo ni aki no umi hiroshi

A diez pasos de casa,

como en un mar me interno

en el otoño

もうもうと牛鳴く星の別れ哉

Mō mō to ushi naku hoshi no wakare kana

Cuando muge

la vaca, las estrellas

inician su adiós

なまくさき漁村の月の踊かな

Namagusaki gyoson no tsuki no odori kana

Pueblo marinero:

bailas a la luna,

hueles a pescado

人かへる花火のあとの暗さ哉

Hito kaeru hanabi no ato no kurasa kana

Los fuegos terminaron

La gente se dispersa

Las tinieblas avanzan

淋しさや花火のあとの星の飛ぶ

Sabishisa ya hanabi no ato no hoshi no tobu

Calma, soledad

Fuegos de artificio

Una estrella fugaz

神に灯をあげて戻れば鹿の声

Kami ni hi wo agete modoreba shika no koe

Una vela prendida a los dioses

y el lamento de un ciervo

mientras retorno

柳散り菜屑流るゝ小川哉

Yanagi chiri nakuzu nagaruru ogawa kana

Caen hojas del sauce

y restos de verduras

que se lleva el arroyo

木立暗く何の實落つる水の音

Kodachi kuraku nan no mi otsuru mizu no oto

Bosque entre sombras

Cae una baya

Eco en el agua

梨むくや甘き雫の刃を垂るゝ

Nashi muku ya amaki shizuku no ha wo taruru

Pelo una pera

Gotas perladas

cuchillo abajo

柿くひの発句好と伝ふべし

Kaki kui no hokku zuki to tsutau beshi

¿Mi biografía?:

“le gustaba aquel haiku

de los kakis”

柿くへば鐘が鳴るなり法隆寺

Kaki kueba kane ga naru nari Hōryū-ji

Como kakis y suenan

campanas de templo

en Hōryūji

三千の俳句を閲し柿二つ

Sanzen no haiku wo kemishi kaki futatsu

Hago balance

Miles de haikus

Un par de caquis

草花の鉢並べたる床屋かな

Kusabana no hachi narabetaru tokoya kana

En la barbería,

hasta las macetas

hacen fila

隣からともしのうつるはせを哉

Tonari kara tomoshibi utsuru bashō kana

La lámpara de al lado

reflejada en las hojas

del banano

我声の風になりけり茸狩

Waga koe no kaze ni nari keri kinoko-gari

Juntar hongos, transformarse

mi voz en el viento

de otoño

飛んで来る余所の落葉や暮るゝ秋

Tonde kuru yoso no ochiba ya kururu aki

Las hojas muertas

llegan de cualquier sitio

mientras muere el otoño

Haikus de invierno

h ttp://traducirjapon.blogspot.hu/2009/05/haikus-de-invierno.html

Trad. de Alberto Silva

物干の影に測りし冬至哉

Monohoshi no kage ni hakarishi tōji kana

Sombra de cañas

de tender ropa: anuncio

del solsticio

de invierno

冬ざれの小村を行けば犬吠ゆる

Fuyuzare no komura wo yukeba inu hoyuru

En pleno invierno,

cuando cruzo la aldea

ladran los perros

十に足らぬ子を寺へやる寒さ哉

Tō ni taranu ko wo tera e yaru samusa kana

Menos de diez años

¡y lo entregan al templo!

(sabor helado)

鼻垂れの子が売れ残る寒哉

Hanatare no ko ga urenokoru samusa kana

Hay figuritas

que nadie compra,

que se mueren de frío

木の影や我影動く冬の月

Ki no kage ya waga kage ugoku fuyu no tsuki

Sombra de los árboles

y la mía que oscila

bajo la luna helada

屋根の上に火事見る人や冬の月

Yane no ue ni kaji miru hito ya fuyu no tsuki

Sobre el techo,

la gente mira fuegos

como quien mira lunas

寒月や石塔の影松のかげ

Kangetsu ya sekitō no kage matsu no kage

Luna invernal

Sombra de la pagoda

y de un pino congelado

牛つんで渡る小船や夕しぐれ

Ushi tsunde wataru kobune ya yūshigure

El lanchón

en la tarde y un toro

en la borda

en la torva invernal

赤き實の一つこぼれぬ霜の庭

Akaki mi no hitotsu koborenu shimo no niwa

Baya,

clavija roja

sobre la escarcha

金殿のともし火細し夜の雪

Kinden no tomoshibi hososhi yoru no yuki

La nieve y la noche

angostan las luces

del palacio

古池のをしに雪降る夕かな

Furuike no oshi ni yuki furu yūbe kana

La nieve que cae

Dos patos solemnes

sobre un antiguo lago

刈り残す薄の株の雪高し

Karinokosu susuki no kabu no yuki takashi

Sobre rabos

de hierba cortada

la densa nevada

十一騎面もふらぬ吹雪かな

Jūi-kki omote mo furanu fubuki kana

Once caballeros

encaran la tormenta

sin darse vuelta

時々に霰となって風強し

Tokidoki ni arare to natte kaze tsuyoshi

Granizo se hace

la lluvia y el viento

no deja de soplar

捨舟の中にたばしる霰かな

Sutebune no naka ni tabashiru arare kana

Barca abandonada

Dentro, el granizo trota,

se desparrama

甲板に霰の音の暗さかな

Kampan ni arare no oto no kurasa kana

En el muelle

el oscuro resón

del granizo

門許り残る冬野の伽藍哉

Mon bakari nokoru fuyuno no garan kana

Tan sólo queda

la puerta de aquel templo

en medio de la taiga

invernal

ところどころ菜畑遠き枯野哉

Tokorodokoro nabatake tōki kareno kana

Perdidos, lejos,

los cuadros de legumbres

en el campo reseco

旅人の蜜柑くひ行く枯野哉

Tabibito no mikan kuiyuku kareno kana

Corre caminos

Come naranjas

Llano reseco

森の中に池あり氷厚き哉

Mori no naka ni ike ari kōri atsuki kana

El estanque del bosque

profundo, el grosor

de la capa de hielo

番小屋に昼は人なき火鉢哉

Bangoya ni hiru wa hito naki hibachi kana

Una garita a mediodía

Un braserito

sin compañía

釈迦に問ふて見たき事あり冬籠

Shaka ni tōte mitaki koto ari fuyugomori

Aislado en el invierno,

le hago consultas

al Despierto

十年の苦学毛の無き毛布哉

Jū-nen no kugaku ke no naki mōfu kana

Diez años

de estudiante pobre (me lo dice

esta hilacha de manta)

![]()

Haïkus de Shiki

Traduit par Daniel Py de la version anglaise de R.H.Blyth

Traductions en français :

Cent sept haiku de Shiki, Verdier 2002. Traducteur Joan Titus-Carmel.

Le mangeur de kakis qui aime les haïkus, de Shiki, Moundarren, 1992. Traducteur Cheng Wing Fun.

![]()

Masaoka Shiki

Ausgewählte Haiku

übersetzt von Thomas Hemstege

Hamburg 2013

http://www.shiki-haiku.de/shiki_gedichte.pdf