Terebess

Asia Online (TAO)

Index

Home

Ezra Loomis Pound (1885-1972)

IN

A STATION OF THE METRO

The

apparition of these faces in the crowd:

Petals on a wet, black bough.

----------------------------------------------------------

Poetry 2:1, Chicago, April 1913.Original Text: Ezra Pound, "Contemporania," Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, 2.1 (April 1913): 6. Ezra Pound, Lustra (London: Elkin Mathews, 1916). See also Ezra Pound's Poetry and Prose: Contributions to Periodicals, prefaced and arranged by Lea Baechler, A. Walton Litz, and James Longenbach (New York and London: Garland, 1991), I (1902-1914): 137.

First Publication Date: 1913.

Representative Poetry On-line: Editor, I. Lancashire; Publisher, Web Development Group, Inf. Tech. Services, Univ. of Toronto Lib.

Edition: RPO 1998. © I. Lancashire, Dept. of English (Univ. of Toronto), and Univ. of Toronto Press 1998.

----------------------------------------------------------

NOTES

Composition Date: ca. 1911-12.

Form: "haiku-like".the metro: the Paris subway system.

See Pound's commentary on this poem in his article "Vorticism," The Fortnightly Review 571 (Sept. 1, 1914): 465-67:Three years ago in Paris I got out of a "metro" train at La Concorde, and saw suddenly a beautiful face, and then another and another, and then a beautiful child's face, and then another beautiful woman, and I tried all that day to find words for what this had meant to me, and I could not find any words that seemed to me worthy, or as lovely as that sudden emotion. And that evening, as I went home along the Rue Raynouard, I was still trying, and I found, suddenly, the expression. I do not mean that I found words, but there came an equation ... not in speech, but in little spotches of colour. It was just that -- a "pattern," or hardly a pattern, if by "pattern" you mean something with a "repeat" in it. But it was a word, the beginning, for me, of a language in colour. I do not mean that I was unfamiliar with the kindergarten stories about colours being like tones in music. I think that sort of thing is nonsense. If you try to make notes permanently correspond with particular colours, it is like tying narrow meanings to symbols.

That evening, in the Rue Raynouard, I realised quite vividly that if I were a painter, or if I had, often, that kind of emotion, or even if I had the energy to get paints and brushes and keep at it, I might found a new school of painting, of "non-representative" painting, a painting that would speak only by arrangements in colour. ....

That is to say, my experience in Paris should have gone into paint ...

The "one image poem" is a form of super-position, that is to say it is one idea set on top of another. I found it useful in getting out of the impasse in which I had been left by my metro emotion. I wrote a thirty-line poem, and destroyed it because it was what we call work "of second intensity." Six months later I made a poem half that length; a year later I made the following hokku-like sentence: --

"The apparition of these faces in the crowd:

Petals, on a wet, black bough."I dare say it is meaningless unless one has drifted into a certain vein of thought. In a poem of this sort one is trying to record the precise instant when a thing outward and objective transforms itself, or darts into a thing inward and subjective."

This particular sort of consciousness has not been identified with impressionist art. I think it is worthy of attention.

----------------------------------------------------------

See also a republication of this essay in Pound's Gaudier-Brzeska: A Memoir (1916; London: New Directions, 1960): 86-89).

The lines have no spaced words in 1916.www.english.uiuc.edu/maps/poets/m_r/pound/metro.htm

----------------------------------------------------------

Richard Aldington, 1892-1962

Penultimate PoetryThe apparition of these poems in a crowd:

White faces in a black dead faint.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"Penultimate Poetry" appeared in Egoist 1 (January 1914), p. 36.

A parody of Pound and the preoccupations of the Imagists, including their Oriental interests. The last of nine sections finds its humour at the expense of the hokku-derived In a Station of the Metro and the form of super-position.

http://themargins.net/anth/1910-1919/aldingtonapparition.html

Ezra

Pound

Selected Short Poems

Ts'ai

Chi'h

The

petals fall in the fountain,

the orange-coloured rose-leaves,

Their ochre

clings to the stone.

Alba

As

cool as the pale wet leaves

of lily-of-the-valley

She lay beside me in the

dawn.

Papyrus

Spring

. . . . . . . . .

Too long . . . . . . . .

Gongula . . . . . . . . .

Fan-Piece, for Her Imperial Lord

O

fan of white silk,

clear as frost on the grass-blade,

You also are laid

aside.

L'Art, 1910

Green

arsenic smeared on an egg-white cloth,

Crushed strawberries! Come, let us

feast our eyes.

Pagani’s, November 8

Suddenly

discovering in the eyes of the very beautiful

Normande cocotte

The eyes

of the very learned British Museum assistant.

The New Cake of Soap

Lo,

how it gleams and glistens in the sun

Like the cheek of a Chesterton.

Women Before a Shop

The

gew-gaws of false amber and false turquoise attract them.

'Like to like nature':

these agglutinous yellows!

Meditatio

When

I carefully consider the curious habits of dogs

I am compelled to conclude

That

man is the superior animal.

When

I consider the curious habits of man

I confess, my friend, I am puzzled.

Coda

O

My songs,

Why do you look so eagerly and so curiously into

people's faces,

Will

you find your lost dead among them?

Liu

Ch’e

http://petersirr.blogspot.com/2006/03/rustling-of-silk.html

The

rustling of the silk is discontinued,

Dust drifts over the court-yard,

There

is no sound of footfall, and the leaves

Scurry into heaps and lie still,

And

she the rejoicer of the heart is beneath them:

A wet leaf that clings to the threshold.

"Ione, Dead the Long Year"

Empty

are the ways,

Empty are the ways of this land

And the flowers

Bend

over with heavy heads.

They bend in vain.

Empty are the ways of this land

Where Ione

Walked once, and now does not walk

But seems like a person

just gone.

Ancient Wisdom, Rather Cosmic

So-shu

dreamed,

And having dreamed that he was a bird, a bee, and a butterfly,

He

was uncertain why he should try to feel like anything else,

Hence his contentment.

The Encounter

All

the while they were talking the new morality

Her eyes explored me.

And when

I arose to go

Her fingers were like the tissue

Of a Japanese paper napkin.

And the Days Are Not Full Enough

And

the days are not full enough

And the nights are not full enough

And life

slips by like a field mouse

Not shaking the grass

Ité ['Go']

Go,

my songs, seek your praise from the young

and from the intolerant,

Move

among the lovers of perfection alone.

Seek ever to stand in the hard Sophoclean

light

And take you wounds from it gladly.

The Bath Tub

AS

a bathtub lined with white porcelain,

When the hot water gives out or goes

tepid,

So is the slow cooling of our chivalrous passion,

O my much praised

but-not-altogether-satisfactory lady.

Post Mortem Conspectu

A

brown, fat babe sitting in the lotus,

And you were glad and laughing

With

a laughter not of this world.

It is good to splash in the water

And laughter

is the end of all things.

The Patterns

Erinna

is a model parent,

Her children have never discovered her adulteries.

Lalage

is also a model parent,

Her offspring are fat and happy.

Horae Beatae Inscripto

How

will this beauty, when I am far hence,

Sweep back upon me and engulf my mind!

How

will these hours, when we twain are gray,

Turned in their sapphire tide, come

flooding o'er us!

Causa

I

join these words for four people,

Some others may overhear them,

O world,

I am sorry for you,

You do not know these four people.

Separation On The River Kiang

Ko-Jin

goes west from Ko-kaku-ro,

The smoke-flowers are blurred over the river.

His

lone sail blots the far sky.

And now I see only the river,

The long Kiang,

reaching heaven.

The Altar

Let

us build here an exquisite friendship,

The flame, the autumn, and the green

rose of love

Fought out their strife here, 'tis a place of wonder;

Where

these have been, meet 'tis, the ground is holy.

Epitaph

Leucis,

who intended a Grand Passion,

Ends with a willingness-to-oblige.

Phyllidula

Phyllidula

is scrawny but amorous,

Thus have the gods awarded her,

That in pleasure

she receives more than she can give;

If she does not count this blessed

Let

her change her religion.

Gentildonna

She

passed and left no quiver in the veins, who now

Moving among the trees, and

clinging

in the air she severed,

Fanning the grass she walked on then, endures:

Grey

olive leaves beneath a rain-cold sky.

Heather

The

black panther treads at my side,

And above my fingers

There float the petal-like

flames.

The

milk-white girls

Unbend from the holly-trees,

And their snow-white leopard

Watches

to follow our trace.

The Picture

The

eyes of this dead lady speak to me,

For here was love, was not to be drowned

out.

And here desire, not to be kissed away.

The eyes of this dead lady

speak to me.

Society

The

family position was waning,

And on this account the little Aurelia,

Who

had laughed on eighteen summers,

Now bears the palsied contact of Phidippus.

An Object

This

thing, that hath a code and not a core,

Hath set acquaintance where might be

affections,

And nothing now

Disturbeth his reflections.

April

Three

spirits came to me

And drew me apart

To where the olive boughs

Lay stripped

upon the ground:

Pale carnage beneath bright mist.

To Dives

Who

am I to condemn you, O Dives,

I who am as much embittered

With poverty

As

you are with useless riches ?

Tame Cat

It

rests me to be among beautiful women

Why should one always lie about such matters?

I

repeat:

It rests me to converse with beautiful women

Even though we talk

nothing but nonsense,

The

purring of the invisible antennae

Is both stimulating and delightful.

Quies

This

is another of our ancient loves.

Pass and be silent, Rullus, for the day

Hath

lacked a something since this lady passed;

Hath lacked a something. 'Twas but

marginal.

Chen-ou Liu, Canada

Three Readings of Ezra Pound’s “Metro Haiku”

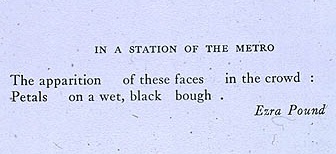

first published in the January 2010 issue of Magnapoets, reprinted in Haiku Reality and Haijinx Quarterly, April, 2010Throughout the history of English poetry, there seldom is a poem like Ezra Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro” (hereafter referred to as “metro poem”) that has been endlessly researched by scholars, literary critics, and poets alike 1. Most of his readers are familiar with at least two versions of his metro poem: the original version published in the April 1913 issue of Poetry as follows:

The apparition . . . of these faces . . in the crowd :

Petals . . . on a wet, black bough.and one of the revised versions published in his 1916 book entitled Lustra as follows:

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;

Petals on a wet, black bough.Everyone may have his/her own reading of this ever-famous poem from different perspectives. But due to the limited space of this article and for Magnapoets readers who are interested in the Asian poetic traditions, I will discuss two major popular readings – the haikuesque and ideogrammatic ones -- in the following sections.

The Haikuesque ReadingIn his most widely-read book, The Haiku Handbook: How to Write, Share, and Teach Haiku, William Higginson rightly emphasizes that Ezra Pound’s metro poem is the “first published hokku in English” 2 and “very important to its author ‘s development” 3. In his essay on “Vorticism” in the September 1914 issue of The Fortnightly Review, Pound “explicitly credits the technique of the Japanese hokku in helping him work out the solution to a ‘metro emotion:’”4

The Japanese have evolved the… form of the hokku… I found it useful in getting out of the impasse in which I had been left by my metro emotion. I wrote a thirty-line poem, and destroyed it because it was what we call work "of second intensity." Six months later I made a poem half that length; a year later I made the following hokku-like sentence:

The apparition of these faces in the crowd:

bbb.Petals, on a wet, black bough.Higginson first points out that the main effect of the change between the 1913 version and 1914 one is “to smooth the rhythm, making the poem less choppy,” 5 and then he focuses the discussion on the most recognizable version by haiku readers, the one that was published in his book, Lustra, as follows:

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;

Petals on a wet, black bough.From the perspective of a haiku poet, Higginson singles out the most important change Pound made: that is the one from the colon at the end of the first line to a semicolon. In his view, a colon tells the reader that the statement made in the first line introduces the statement made in the second, making one a metaphor for the other. Conversely, a semicolon shows that two statements are independent of each other, though maybe related, and that both images -- “faces” and “petals” -- portrayed in the poem are real and stand out against its own background 6. As Higginson stresses, “by revising the poem Pound turned an otherwise sentimental metaphor into a genuine haiku … This is a haiku that Shiki would have been proud to write.” 7 But based on Basho’s teaching of what a real haiku is in the case regarding his revision of the “dragonfly haiku” by his pupil, Kikaku, when composing a haiku by contrasting and comparing two images of different importance, the poet should utilize the lesser image in a manner which will make it seem to suggest the greater image 8. Thus, if Pound’s poem is changed to the following:

Petals on a wet, black bough;

The apparition of these faces in the crowd.I think this will be a haiku that Basho would have been proud to write.

The Ideogrammatic ReadingHowever, Higginson’s reading of the metro poem is chiefly through the haiku lens, and he doesn’t consider the contexts of Pound’s struggle with a new kind of poetry, not just with one poem, and of the growing impacts of the Chinese language in general, and Chinese poetry in particular, upon his view of writing poetry. Outside the haiku community, the metro poem is viewed as a haiku-like, yet a new kind of poem: the most influential imagist poem based on his ideogrammatic poetics. In the introduction of The Norton Anthology of American Literature (Volume D), it firmly states: "Pound first campaigned for 'imagistic,' his name for a new kind of poetry. Rather than describing something - an object or situation - and then generalizing about it, imagist poets attempted to present the object directly, avoiding the ornate diction and complex but predictable verse forms of traditional poetry."

Following Ernest Fenollosa's view of the Chinese written language as a medium for poetry, Pound bases his ideogrammic poetics on the false assumptions that Chinese characters are essentially ideographic and non-phonetic in nature , and that the sense of individual characters is visually generated by the juxtaposition of their graphic components 9. The famous example used by his mentor, Fenollosa, is the following:

MAN SEES HORSE

“First stands the man on his two legs. Second, his eye moves through space; a bold figure represented by running legs under an eye, a modified picture of an eye, a modified picture of running legs, but unforgettable once you have seen it. Third stands the horse on his four legs ... Legs belong to all three characters; they all alive. The group holds something of the quality of a continuous moving picture.” 10 Fenollosa claims, and Pound echoes him, that the Chinese ideogram presents a necessary relationship between its components: “eye on legs” can only mean “see,” because in “this process of compounding, two things added together do not produce a third thing but suggest some fundamental relation between them.” 11

The 1913 original printing of the poem, which is completely not discussed by Higginson, Pound emphasizes the intervals that punctuate the poem, each semantic unit of words functioning as a discrete character, three characters to each line. His “ideogrammic juxtaposition” of images is relatively simple and straightforward, and through the metaphoric suggestion of the catalyzing word “apparition,” Pound combines the mundane image of "faces in the crowd," with an image possessing visual beauty and the rich cultural-aesthetical connotations of countless poems about spring. There is a quick transition from the factual statement of the first line to the vivid metaphor of the second one. As Carol Percy emphasizes, “what Pound wants is to bring out ‘some fundamental relation between things’: the two lines are juxtaposed, and this should enable one to read them in much the same way that he believed a Chinese person would read ‘eye on legs’ as ‘see.’” 12

For anyone who is interested in understanding the writing process of an innovative poet, no matter which reading of Pound's metro poem one would adopt, the heart of the poem lies in relation. In his view, “relations are more real and more important than the things relate,” on which Pound adds a footnote: “Compare Aristotle’s Poetics: Swift perception of relations, hallmark of genius. 13” " As one who is an English learner as well as a struggling “poet”, I can identify with Pound’s six-year epic struggle with one poem, which embodies his audacious proclamation of “Make it new!” Every time when I confront the following impasse:

Respect English

is whispered into my left ear

Make it new

into my right --

the page remains blankI always think of Ezra Pound:

an American

unties tangled threads

innocent

of Chinese ideograms

and weaves them anew

Notes:1 For anyone who is interested in getting a glimpse into the different readings of Pound’s metro poem, MAPS offers a helpful webpage entitled On "In a Station of the Metro," which can be accessed at http://www.english.illinois.edu/Maps/poets/m_r/pound/metro.htm

2 Higginson, William J. (with Penny Harter). The Haiku Handbook: How to Write, Share, and Teach Haiku. McGraw-Hill Book. 1989. p. 51

3 Ibid, p. 134.

4 Ibid, p. 135.

5 Ibid, p. 135.

6 Ibid, pp. 135-6.

7 Ibid, p.136.

8 In his book entitled An Introduction to Haiku: An Anthology of Poems and Poets from Basho to Shiki, Harold Henderson talks about a story about how to write a real haiku. One day, while walking with his teacher, Basho, on a country road, Kikuka was deeply moved by the sight of the dragonflies flying about and wrote the following haiku:

Red dragonflies! Take off their wings,

and they are pepper pods!Basho relied that such a haiku was not a real one, and he revised it as follows:

Red pepper pods! Add wings to them,

and they are dragonflies!For further details, see pp. 17-8.

And Richard Eugene Smith gives a good analysis of this story in his essay titled Ezra Pound and the Haiku (College English, Vol. 26, No. 7 (Apr., 1965), pp. 522-527)

9 Weinberger, Eliot and Williams, William Carlos, ed. The New Directions Anthology of Classical Chinese Poetry. New Directions. 2003. pp. xviii-xxiii.

10 Fenollosa, Ernest. The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry. Ed. Ezra Pound. City Lights. 1936. pp. 8-9.

11 Ibid.

12 Percy , Carol. Ezra Pound and the Chinese Written Language. http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/~cpercy/courses/6362Pickard2.htm

13 Fenollosa, Ernest. p. 22.

Cf.

CATHAY

translations & transformations by Heinz Insu Fenkl

Codhill Press, New Paltz ≈ New York, 2007