Terebess

Asia Online (TAO)

Index

Home

松尾芭蕉 Matsuo Bashō (1644-1694)

![]()

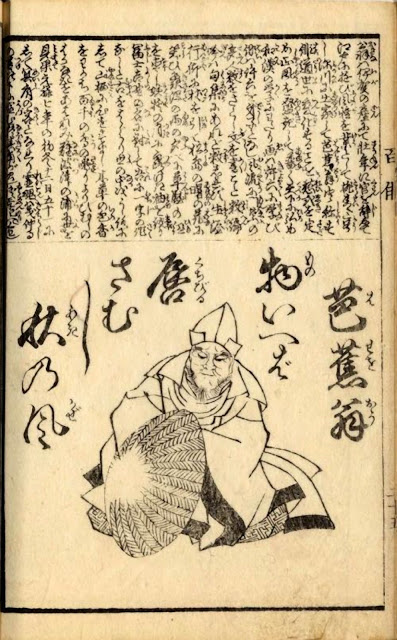

「芭蕉行脚図 」 Matsuo Bashō

and Kawai Sora

on pilgrimage,

painted by 森川許六 Morikawa Kyoriku (1656-1715) in 1693

cf.

鹿島詣 Kashima kikō — 1687

![]() Matsuo Bashō's haiku poems in romanized Japanese with English translations (Editor: Gábor Terebess, Hungary)

Matsuo Bashō's haiku poems in romanized Japanese with English translations (Editor: Gábor Terebess, Hungary)

Matsuo

Basho's Narrow Road to the Deep North tr. by Nobuyuki Yuasa

![]() Matsuo Bashô's Complete Haiku in

Japanese (alphabetical order) (DOC)

Matsuo Bashô's Complete Haiku in

Japanese (alphabetical order) (DOC)

![]() BASÓ: Régi tó vizet csobbant Macuo Basó 630 haikuja HTML > ábécérendben DOC kétnyelvű

BASÓ: Régi tó vizet csobbant Macuo Basó 630 haikuja HTML > ábécérendben DOC kétnyelvű

Bashō’s Journey: the literary prose of Matsuo Bashō

translated with an introduction by David Landis Barnhill.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Contents: Journey of bleached bones (Nozarashi Kiko) — Kashima journal

(Kashima kiko) — Knapsack notebook (Oi no kobumi) — Sarashina journal

(Sarashina kiko) — The narrow road to the deep north (Oku no hosomichi)

— Saga diary (Saga nikki) — Selected haibun.

Bashô's

Haiku

translated David

Landis Barnhill.

Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press, 2004, 331 pp

Basho: The Complete

Haiku. Intr. & tr. by Jane Reichhold,

Kodansha International, 2008, 432 pages

Bashō: The Complete Haiku of Matsuo Bashō

Translated, Annotated, and with an Introduction by Andrew Fitzsimons

2022

A Zen Wave: Basho's Haiku and Zen by Robert Aitken

Narrow Road to the Interior and Other Writings, translated by Sam Hamill

Contents: Narrow road to the interior—Travelogue of weather-beaten bones—The knapsack

notebook—Sarashina travelogue—Selected haiku.

"No matter where your interest lies, you will not be able to accomplish anything unless you bring your deepest devotion to it." - Matsuo Basho

Basho

"In the second year of the Jokyo period (1685) at dawn on the 14th day of

the Ninth Month, Basho had a strange dream in which he was caught in a rainstorm

and ran into a shrine to take shelter. The priest scolded him and turned him away,

but then said he could stay if he could make a haiku that fit the moment. Basho

replied, 'Oh, well, at this very place ...' and produced a haiku." - Reference:

volume IX of the complete works of Basho published by Kadokawa Shoten

Matsuo

Munefusa, alias Basho (1644-94), was a Japanese poet and writer during the early

Edo period. He took his pen name Basho from his basho-an, a hut made of plantain

leaves, to where he would withdraw from society for solitude. Born of a weathy

family, Basho was a Samurai until the age of 20, at which time he devoted himself

to his poetry. Basho was a main figure in the development of haiku, and is considered

to have written the most perfect examples of the form. His poetry explores the

beauties of nature and are influenced by Zen Buddhism, which lends itself to the

meditative solitude sensed in his haiku. He traveled extensively throughout his

lifetime. His 1689 five-month journey deep into the country north and west of

Edo provided the insight for his most famous work Oku no hosomichi (Narrow Road

to the Deep North). This great work was posthumoustly published in 1702 and is

still read by most Japanse high school students.

Interestingly,

in 1996 an article in AsiaWeek claimed in the original manuscript of The Narrow

Road to the Deep North was found in the library of an Osaka bookseller. It appears

the manuscript was discovered after an earthquake. A scholar spent 6 years studying

the work before declaring a 99% certainty that the manuscript was authentic. Read

an article published on Stone Bridge Press.

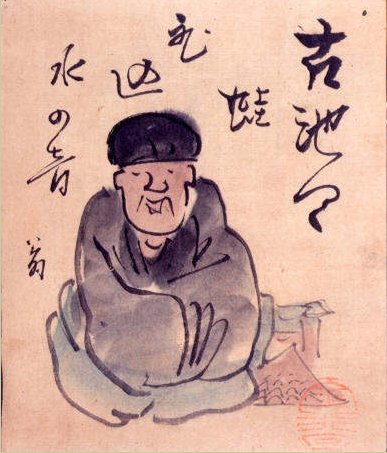

Bashō's

Haiku

横井金谷 Yokoi Kinkoku (1761-1832): Basho with his "Frog" poem (c.1820)

Old

pond

a frog jumps in

the sound of water

Evening

rain:

the basho

speaks of it first

With

what kind of voice

would the spider cry

in the autumn wind?

drinking

morning tea

the monk is peaceful

the chrysanthemum blooms

Falling

ill while on a journey,

I still wander around the wilderness,

in my

dreams

This

autumn

why do I feel old?

a bird in a cloud

Walking

with canes

one grey-haired family

is visiting graves

The scent of plum

blossoms

on the misty mountain path

a big rising sun

Exhausted

I sought

a country inn, but found

wisteria in bloom

An example

of different translations:

Awakened

when the ice

bursts the waterjar

Ice

in the night -

the waterjar cracks,

waking me

Spring breeze

a pipe in his mouth -

the boatman

Travelling

this high

mountain trail, delighted

by violets

Temple

bells die out

the fragrant blossoms remain

A perfect evening!

Your

song caresses

the depths of loneliness,

O high mountain bird

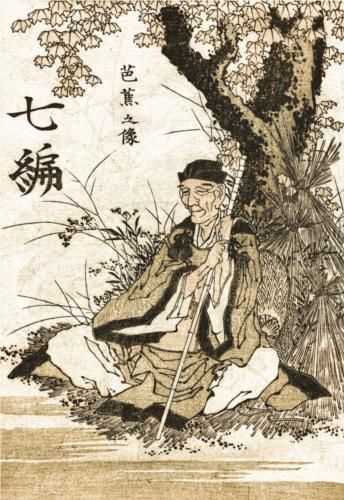

Portrait of Basho by

葛飾北斎 Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849)

Basho's Haiku

Japanese Haiku,

by Peter Beilenson, [1955]

(©

Peter Beilenson)

BALLET IN THE

AIR ...

TWIN BUTTERFLIES

UNTIL, TWICE WHITE

THEY MEET, THEY MATE

BLACK CLOUDBANK

BROKEN

SCATTERS IN THE

NIGHT ... NOW SEE

MOON-LIGHTED MOUNTAINS!

SEEK ON HIGH

BARE TRAILS

SKY-REFLECTING

VIOLETS...

MOUNTAIN-TOP JEWELS

FOR A LOVELY

BOWL

LET US ARRANGE THESE

FLOWERS...

SINCE THERE IS NO RICE

NOW THAT EYES

OF HAWKS

IN DUSKY NIGHT

ARE DARKENED...

CHIRPING OF THE QUAILS

APRIL'S AIR

STIRS IN

WILLOW-LEAVES ...

A BUTTERFLY

FLOATS AND BALANCES

IN THE SEA-SURF

EDGE

MINGLING WITH

BRIGHT SMALL SHELLS ..

BUSH-CLOVER PETALS

THE RIVER

GATHERING MAY RAINS

FROM COLD STREAMLETS

FOR THE SEA ...

MURMURING MOGAMI

WHITE CLOUD

OF MIST

ABOVE WHITE

CHERRY-BLOSSOMS ...

DAWN-SHINING MOUNTAINS

TWILIGHT WHIPPOORWILL

...

WHISTLE ON,

SWEET DEEPENER

OF DARK LONELINESS

MOUNTAIN-ROSE

PETALS

FALLING, FALLING,

FALLING NOW ...

WATERFALL MUSIC

AH ME! I AM

ONE

WHO SPENDS HIS LITTLE

BREAKFAST

MORNING-GLORY GAZING

SEAS ARE WILD

TONIGHT...

STRETCHING OVER

SADO ISLAND

SILENT CLOUDS OF STARS

WHY SO SCRAWNY,

CAT?

STARVING FOR FAT FISH

OR MICE ...

OR BACKYARD LOVE?

DEWDROP, LET

ME CLEANSE

IN YOUR BRIEF

SWEET WATERS ...

THESE DARK HANDS OF LIFE

GLORIOUS THE

MOON...

THEREFORE OUR THANKS

DARK CLOUDS

COME TO REST OUR NECKS

UNDER CHERRY-TREES

SOUP, THE SALAD,

FISH AND ALL ...

SEASONED WITH PETALS

TOO CURIOUS

FLOWER

WATCHING US PASS,

MET DEATH...

OUR HUNGRY DONKEY

CLOUD OF CHERRY-BLOOM

...

TOLLING TWILIGHT

BELL ... TEMPLE

UENO? ASAKUSA?

MUST SPRINGTIME

FADE?

THEN CRY ALL BIRDS ...

AND FISHES'

COLD PALE EYES POUR TEARS

SUCH UTTER SILENCE!

EVEN THE CRICKETS’

SINGING...

MUFFLED BY HOT ROCKS

SWALLOW IN THE

DUSK...

SPARE MY LITTLE

BUZZING FRIENDS

AMONG THE FLOWERS

OLD DARK SLEEPY

POOL...

QUICK UNEXPECTED

FROG

GOES PLOP! WATERSPLASH!

DARTING DRAGON-FLY

...

PULL OFF ITS SHINY

WINGS AND LOOK...

BRIGHT RED PEPPER-POD (KIKAKU)

REPLY:

BRIGHT RED PEPPER-POD

...

IT NEEDS BUT SHINY

WINGS AND LOOK...

DARTING DRAGON-FLY!

WAKE! THE SKY

IS LIGHT!

LET US TO THE ROAD

AGAIN...

COMPANION BUTTERFLY!

SILENT THE OLD

TOWN...

THE SCENT OF FLOWERS

FLOATING...

AND EVENING BELL

CAMELLIA-PETAL

FELL IN SILENT DAWN ...

SPILLING

A WATER-JEWEL

IN THE TWILIGHT

RAIN

THESE BRILLIANT-HUED

HIBISCUS ...

A LOVELY SUNSET

LADY BUTTERFLY

PERFUMES HER WINGS

BY FLOATING

OVER THE ORCHID

NOW THE SWINGING

BRIDGE

IS QUIETED

WITH CREEPERS...

LIKE OUR TENDRILLED LIFE

THE SEA DARKENING...

OH VOICES OF THE

WILD DUCKS

CRYING, WHIRLING, WHITE

NINE TIMES ARISING

TO SEE THE MOON...

WHOSE SOLEMN PACE

MARKS ONLY MIDNIGHT YET

HERE, WHERE

A THOUSAND

CAPTAINS SWORE GRAND

CONQUEST ... TALL

GRASS THEIR MONUMENT

NOW IN SAD AUTUMN

AS I TAKE MY

DARKENING PATH ...

A SOLITARY BIRD

WILL WE MEET

AGAIN

HERE AT YOUR

FLOWERING GRAVE...

TWO WHITE BUTTERFLIES?

DRY CHEERFUL

CRICKET

CHIRPING, KEEPS

THE AUTUMN GAY ...

CONTEMPTUOUS OF FROST

FIRST WHITE

SNOW OF FALL

JUST ENOUGH TO BEND

THE LEAVES

OF FADED DAFFODILS

CARVEN GODS

LONG GONE...

DEAD LEAVES ALONE

FOREGATHER

ON THE TEMPLE PORCH

COLD FIRST WINTER

RAIN...

POOR MONKEY,

YOU TOO COULD USE

A LITTLE WOVEN CAPE

NO OIL TO READ

BY ...

I AM OFF TO BED

BUT AH!...

MY MOONLIT PILLOW

THIS SNOWY MORNING

THAT BLACK CROW

I HATE SO MUCH...

BUT HE'S BEAUTIFUL!

IF THERE WERE

FRAGRANCE

THESE HEAVY SNOW-

FLAKES SETTLING...

LILIES ON THE ROCKS

SEE: SURVIVING

SUNS

VISIT THE ANCESTRAL

GRAVE ...

BEARDED, WITH BENT CANES

DEATH-SONG:

FEVER-FELLED HALF-WAY,

MY DREAMS AROSE

TO MARCH AGAIN...

INTO A HOLLOW LAND

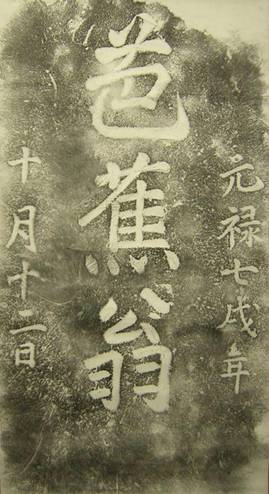

Matsuo Basho by 杉山杉風 Sugiyama Sanpū (1647-1732)

He was one of the Basho jittetsu 芭蕉十哲 10 most important followers.

Poet's

Corner - Biography

Matsuo Basho (1644-1694)

On

high narrow road

old traveler clears wide swath,

tiny scythe glinting.

Old

pond...

a frog leaps in

water's sound.

To

a leg of a heron

Adding a long shank

Of a pheasant.

Matsuo

Basho (1644-1694) was one of the greatest Japanese poets. He elevated haiku to

the level of serious poetry in numerous anthologies and travel diaries.

The

name of Matsuo Basho is associated especially with the celebrated Genroku era

(ca. 1680-1730), which saw the flourishing of many of Japan's greatest and most

typical literary and artistic personalities. Although Basho was the contemporary

of writers like the novelist and poet Ihara Saikaku and the dramatist Chikamatsu

Monzaemon, he was far from being an exponent of the new middle-class culture of

the city dwellers of that day. Rather, in his poetry and in his attitude toward

life he seemed to harken back to a period some 300 years earlier. An innovator

in poetry, spiritually and culturally he maintained a great tradition of the past.

The haiku, a 17-syllable verse form divided into successive phrases or lines of 5, 7, and 5 syllables, originated in the linked verse of the 14th century, becoming an independent form in the latter part of the 16th century. Arakida Moritake (1473-1549) was a distinguished renga poet who originated witty and humorous verses he called haikai, which later became synonymous with haiku. Nishiyama Soin (1605-1682), founder of the Danrin school, pursued Arakida's ideals. Basho was a member of this school at first, but breaking with it, he was responsible for elevating the haiku to a serious art, making it the verse form par excellence, which it has remained ever since.

Basho's poetical works, known as the Seven Anthologies of the Basho School (Basho Schichibushy), were published separately from 1684 to 1698, but they were not published together until 1774. Not all of the approximately 2,500 verses in the Basho anthologies are by Basho, although he is the principal contributor. Eleven other poets, his disciples, also contributed poems. These anthologies thus reflect composition performed by groups of poets with Basho as the arbiter of taste, injecting his comments on the poems of others, arranging his works in favorable contrast to theirs, and generally having the "last word." It was understood that he was the first poet of his group, and he expected a considerable amount of deference.

Early Life and Works

Basho was born in 1644 in Ueno, lga Province, part of present-day Mie Prefecture. He was one of six children in a family of samurai, descended, it is said, from the great Taira clan of the Middle Ages. As a youth, Basho entered feudal service but at the death of his master left it to spend much of his life in wandering about Japan in search of imagery. Thus he is known as a traveler as well as a poet, the author of some of the most beautiful travel diaries ever written in Japanese. Basho is thought to have gravitated toward Kyoto, where he studied the Japanese classics. Here, also, he became interested in the haiku of the Teitoku school, which was directed by Kitamura Kigin.

In 1672, at the age of 29, Basho set out for Edo (modern Tokyo), the seat of the Tokugawa shoguns and defacto capital of Japan. There he published a volume of verse in the style of the Teitoku school called Kai-Oi. In 1675 he composed a linked-verse sequence with Nishiyama Soin of the Danrin school, but for the next 4 years he was engaged in building waterworks in the city to earn a living. Thereafter, generous friends and admirers made it possible for him to continue a life devoted to poetic composition, wandering, and meditation, though he seems to have been largely unconcerned with money matters.

In 1680, thanks to the largesse of an admirer, Basho established himself in a small cottage at Fukagawa in Edo, thus beginning his life as a hermit of poetry. A year later one of his followers presented him with a banana plant, which was duly planted in Basho's garden. His hermitage became known as the Hermitage of the Banana Plant (Basho-an), and the poet, who had heretofore been known by the pen name Tosei, came increasingly to use the name Basho.

The hermitage burned down in 1682, causing Basho to retire to Kai Province. About this time it is believed that Basho began his study of Zen at the Chokei Temple in Fukagawa, and it has often been assumed erroneously that Basho was a Buddhist priest. He dressed and conducted himself in a clerical manner and must have been profoundly motivated by a mystical faith. Whatever experiences of tragedy or strong emotion that he suffered seem to have enlarged his perception of reality. His vision of the universe is implicit in all his best poems, and the word zen has often been applied to him and his work. His work and later life certainly could not be called worldly.

Travel Diaries

In 1683 the hermitage was rebuilt and Basho returned to Edo. But in the summer of 1684 Basho made a journey to his birthplace, which resulted in the travel diary The Weatherbeaten Trip (Nozarashi Kiko). That same year he published the haiku collection entitled Winter Days (Fuyu no Hi). It was in Winter Days that Basho enunciated his revolutionary style of haiku composition, a manner so different from the preceding haiku that the word "shofu" (haiku in the Basho manner) was coined to describe it.

Winter Days, published in Kyoto, was compiled under Basho's direction by his Nagoya disciple Yamamoto Kakei. Basho, wintering at Nagoya on his trip home to lga, had summoned his disciples to compose a haiku sequence inspired by the season. Basho set the tone for the sequence by using the words "wintry blasts" in the first poem. The progress of the seasons was one of the main inspirations for the anthology, putting it in tune with the cosmic process. Nature, the understanding of its beauty and acceptance of its force, is used by Basho to express the beauty which he observes in the world. Basho enunciates the abstract beauty, yugen, which lies just behind the appearance of the world. The word "yugen" may be understood as the inner beauty of a work of art or nature which is rarely apparent to the vulgar. And the apprehension of this beauty gives the beholder a momentary intimation, an illumination, of the deeper significance of the universe about him. This view of the universe, while not original with Basho, was in his case undoubtedly inspired by some previous experience.

In 1686 Spring Days (Haru no Hi) was compiled in Nagoya by followers of Basho, revised by him, and published in Kyoto. There is an attitude of refined tranquility in these poems representing a deeper metaphysical state. The anthology contains one of the most famous of all Basho's haiku verse: "An old pond/ a frog jumps in/ splash!" There has been much speculation on the significance of this verse, which has captured the fancy of many generations of lovers of Japanese poetry. But even the imagery alone can be appreciated by many different people at a variety of levels. Composition within the delicate confines of haiku versification definitely sets Basho off as one of the greatest mystical poets of Japan. The simplicity it exhibits is the result of the methodical rejection of much complication, not the simplicity with which one starts but rather that with which one ends.

In the autumn of 1688 Basho went to Sarashina, in present-day Nagano Prefecture, to view the moon, a hallowed autumn pastime in Japan. He recorded his impressions in The Sarashina Trip (Sarashina Kiko). Though one of his lesser travel diaries, it is a kind of prelude to his description of a journey to northern Japan a year later. It was at this time that Basho also wrote a short prose account of the moon as seen from Obasute Mountain in Sarashina. The legend of the mountain, where an old woman was abandoned to die alone, moved him also to compose a verse containing the image of an elderly woman accompanied only by the beautiful moon of Sarashina.

The Journey to Ou (Oku no Hosomichi) is perhaps the greatest of Basho's travel diaries. A mixture of haiku and haibun, a prose style typical of Basho, it contains some of his greatest verses. This work immortalizes the trip Basho made from Sendai to Shiogama on his way to the two northernmost provinces of Mutsu and Dewa (Ou). This diary reflects how the very thought of the hazardous journey, a considerable undertaking in those days, filled Basho with thoughts of death. He thinks of the Chinese T'ang poets Li Po and Tu Fu and the Japanese poets Saigyo and Sogi, all of whom had died on journeys.

Setting out early in the spring of 1689 from Edo with his disciple Kawai Sora, Basho traveled for 5 months in remote parts of the north, covering a distance of some 1,500 miles. The poet saw many notable places of pilgrimage, including the site of the hermitage where Butcho had practiced Zen meditation. The entire trip was to be devoted to sight with historical and literary associations, but Basho fell ill and again speculated on the possibility of his dying far from home. But he recovered and continued on to see the famous island of Matsushima, considered one of the three scenic wonders of Japan.

He proceeded to Hiraizumi to view ruins dating from the Heian Period. On the site of the battlefield where Yoshitsune had fallen, Basho composed a poem: "A wilderness of summer grass/ hides all that remains/ of warriors' dreams." In the province of Dewa he was fortunate enough to find shelter at the home of a well-to-do admirer and disciple. Passing on to a temple, Risshakuji, Basho was deeply inpired by the silence of the place situated amidst the rocks. It occasioned the verse which some consider his masterpiece: "Stillness!/ It penetrates the very rocks/ the shrill-chirping of the cicadas."

Crossing over to the coast of the Sea of Japan, Basho continued southwest on his journey to Kanazawa, where he mourned at the grave of a young poet who had died the year before, awaiting Basho's arrival. He continued to Eiheiji, the temple founded by the great Zen priest Dogen. Eventually there was a reunion with several of his disciples, but Basho left them again to travel on to the Grand Shrine of Ise alone. Here the account of this journey ends. The work is particularly noteworthy for the excellence of its prose as well as its poetry and ranks high in the genre of travel writing in Japanese literature. Basho continued to polish this work until 1694; it was not published until 1702.

Mature Works

In 1690 Basho lived for a time in quiet retirement at the Genju-an ("Unreal Dwelling") near Lake Biwa, north of Kyoto, and he wrote an account of this stay. Early in 1691 he stayed for a time in Saga with his disciple Mukai Kyorai.

As for his poetry, Waste Land (Arano) had been compiled by the disciple Kakei and published in 1689. It is the largest of the anthologies and contains a preface by Basho in which he characterizes his preceding anthologies as "flowery" and henceforth establishes a new standard of metaphysical and esthetic depth for haiku. The Gourd (Hisago) was compiled by the disciple Chinseki at Zeze in the province of Omi in 1690. It foreshadows in its excellence the mature and serious versifying which was to be the hallmark of the anthology The Monkey's Raincoat (Sarumino) in 1691. Compiled by Basho's disciples under his attentive supervision, The Monkey's Raincoat is composed of a judicious selection of haiku from the hands of many poets.

It was while Basho was staying at the hermitage in Omi during the spring and summer of 1690 that the compilation was made. The Monkey's Raincoat contains some of Basho's own finest and essential haiku. This anthology, which may be compared with the finest anthologies in the history of Japanese literature, is arranged according to the four seasons. The title is taken from the opening verse by Basho, a poem of winter: "First cold Winter rain/ even the monkey seems to want/ a tiny raincoat." Basho leads the contributors with the largest number of poems, followed by Boncho and Kyorai. But all the verses conform to Basho's tastes. The poems are linked by a subtle emotion rather than by a logical sequence, but they belong together.

In the late fall of 1691 Basho returned to Edo, where a new Banana Hermitage had been built near the site of the former one, complete with another banana plant in the garden. For the next 3 years Basho remained there receiving his disciples, discussing poetry, and helping in the compilation of another anthology, The Sack of Charcoal (Sumidawara) of 1694. The reason for the title, according to the preface, is that Basho, when asked if such a word could be used in haiku poetry, replied that it could. This anthology, together with its successor, The Sequel to the Monkey's Raincoat (Zoku Sarumino), exhibits the quality of Karumi, or lightness, an artistic spontaneity which is the fruit of a lifetime of poetic cultivation. It is a kind of sublimity reached by a truly great poet and cannot be imitated intellectually. The Sequel to the Monkey's Raincoat in 1698, appearing 4 years after Basho's death, is concerned with the seasons, traveling, and religion. It contains some of Basho's last and most mature poems.

In the spring of 1694 Basho set out for what was to be his last journey to his birthplace. At Osaka he was taken ill. Perceiving that he was near his end, Basho wrote a final poem on his own death: "Stricken while journeying/ my dreams still wander about/ but on withered fields."

FURTHER READINGS

Information on Basho and his works is available in Donald Keene, Anthology of Japanese Literature: From the Earliest Era to the Mid-Nineteenth Century (1955); Kenneth Yasuda, The Japanese Haiku: Its Essential Nature, History and Possibilities in English (1957); Harold G. Henderson, ed. and trans., An Introduction to Haiku: An Anthology of Poems from Basho to Shiki (1958); Ryusaku Tsunoda, William Theodore de Bary, and Donald Keene, eds., Sources of the Japanese Tradition (1958; rev. ed., 2 vols., 1964), an anthology with commentary; R. H. Blyth, A History of Haiku (2 vols., 1963); Makoto Ueda, Zeami, Basho, Yeats, Pound: A Study in Japanese and English Poetics (1965); and Nobuyuki Yuasa's introduction to his translation of Basho's The Narrow Road to the Deep North and Other Travel Sketches (1966).

Source: Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2nd ed. 18 vols. Gale Research, 1998.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

Matsuo

Basho (1644-1694)

A Haiku poet

of the early Edo period who was born into a samurai family in Ueno, Iga Province

where he served Yoshitada the son of the local feudal lord Todo Yoshikiyo. He

was also known by his "haiku" penname of Sengin. He became interested

in poetry and studied "haiku" in Kyoto under the master classics scholar

and poet of the early Edo period Kitamura Kigin (1624? _ 1705).

Matsuo Basho later moved to Edo (the old name of Tokyo) and settled in a small

hermitage called Basho An. Here, together with his disciples he established

his own "haiku" style known as "Sho Fu" (Basho style). His

poetry went beyond the conventional style of the "Danrin" (A "haiku"

school headed by Nisiyama Soin that had become popular because of colloquial

content and light humour). He was to elevate "haikai" (the original

form of "haiku") to a sophisticated literary art. It emphasizes the

atmosphere of "sabi" (elegant simplicity), "shiori" (a deep

sympathetic feeling for both nature and humanity), "hosomi" (understatement)

and "karomi" (a light tone). It is also focussed on the mood of "yugen",

spiritual profundity expressing the inner beauty of art and nature and "kanjaku",

a serene desolation.

His compositions scarcely cling to the classic style, typically adopting sets

of "mae-ku" (preceding verse) and "tsuke-ku" (linking verse,

joined verse or added verse) formed by adding a short verse of 7-7 syllables

to a long verse of 5-7-5 syllables or vice versa. His compositions feature in

particular the fashion of appending a tag verse to provide an enhancing "perfume"

associated with the afterglow of the initial verse.

He also journeyed across Japan visiting a number of districts. After composing

numerous "haiku" poems and prose pieces including travel journals,

he died in a country inn in Naniwa (now Osaka prefecture).

Basho's "haiku" express drama, humor, sadness, ecstasy and confusion

in somehow exaggerated ways. These poetic expressions have a paradoxical nature.

The humor and the despair that he expresses are not implements to encourage

a belief in human potential or to glorify it. If anything, Basho's oeuvre characteristically

announces more his belief in the mediocrity of human existence the more he describes

men's deeds and this makes us conscious of the greatness of the power of nature.

His "haiku" verses were gathered in the "Haikai shichibushu"

(the Seven Anthologies of the Basho School). His major travel journals and diaries

are "Nozarashi kiko" (the Weatherbeaten Trip), "Sarashina kiko"

(the Sarashina Trip), "Oku no hosomichi" (the Narrow Road to the Deep

North) and "Saga nikki" (the Saga Diary).

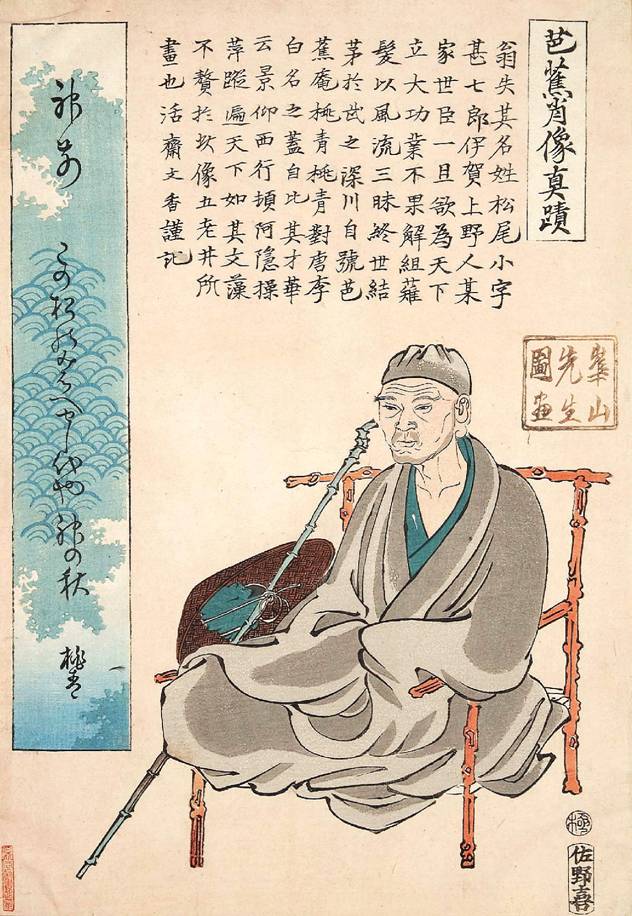

Portrait of Bashō painted by 西村定雅 Nishimura Teiga (1744-1826)

Basho Matsuo (1644 ~ 1694)

Basho Matsuo is known as the first great poet in the history of haikai (and haiku).

He too, wrote poems using jokes and plays upon words in his early stages, as they were in fashion, but began to attach importance to the role of thought in haikai (especially in hokku) from around 1680.

The thought of Tchouang-tseu, philosopher in the 4th century B.C., influenced greatly Basho, and he often quoted the texts of "The Book of master Tchouang" in his hokkus.

The thinker Tchouang-tseu denied the artificiality and the utilitarianism, seeing value of intellect low. He asserted that things seemingly useless had the real value, and that it was the right way of life not to go against the natural law.

To a leg of a heron

Adding a long shank

Of a pheasant.

Basho

This poem parodied the following text in "The Book of master Tchouang":

"When you see a long object, you don't have to think that it is too long

if being long is the property given by the nature. It is proved by the fact that

a duckling, having short legs, will cry if you try to draw them out by force,

and that a crane, having long legs, will protest you with tears if you try to

cut them with a knife."

By playing on purpose in this haiku an act "jointing legs of birds by force" which Tchouang denied, he showed the absurdity of this act and emphasized the powerlessness of the human being's intelligence humorously.

Basho's haikus are dramatic, and they exaggerate humor or depression, ecstasy or confusion. These dramatic expressions have a paradoxical nature. The humor and the despair which he expressed are not implements to believe in the possibility of the human being and to glorify it. If anything, the literature of Basho has a character that the more he described men's deeds, the more human existence's smallness stood out in relief, and it makes us conscious of the greatness of nature's power.

The wind from Mt. Fuji

I put it on the fan.

Here, the souvenir from Edo.

*Edo: the old name of Tokyo.

Sleep

on horseback,

The far moon in a continuing dream,

Steam of roasting tea.

Spring

departs.

Birds cry

Fishes' eyes are filled with tears

Summer

zashiki

Make move and enter

The mountain and the garden.

*zashiki: Japanese-style room covered with tatamis and open to the garden.

What

luck!

The southern valley

Make snow fragrant.

A

autumn wind

More white

Than the rocks in the rocky mountain.

From

all directions

Winds bring petals of cherry

Into the grebe lake.

Even

a wild boar

With all other things

Blew in this storm.

The

crescent lights

The misty ground.

Buckwheat flowers.

Bush

clover in blossom waves

Without spilling

A drop of dew.

Note:

Originally, Basho didn't write the poem "To a leg of a heron..."

as a hokku, but as one of verses in a haikai-renga.

This verse suggests the

intention to laugh at himself: "What a stupid deed like drawing out a heron's

leg it is to product one more series of haikai! Because it is produced so often."

Written

by

Ryu Yotsuya

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

![]()

Portrait of Bashō painted by

上村白鴎

Kamimura Hakuō (1754-1832)

The Basho Museum (芭蕉記念館 Bashō

Kinenkan), 1-6-3 Tokiwa, Koto-ku, Tokyo

The master haiku Poet Matsuo Basho

by Makoto Ueda,

Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1970.

Basho's Life

One day in the spring of 1681 a banana tree was being planted alongside a modest

hut in a rustic area of Edo, a city now known as Tokyo. It was a gift from a local

resident to his teacher of poetry, who had moved into the hut several months earlier.

The teacher, a man of thirty-six years of age, was delighted with the gift. He

loved the banana plant because it was somewhat like him in the way it stood there.

Its large leaves were soft and sensitive and were easily torn when gusty winds

blew from the sea. Its flowers were small and unobtrusive; they looked lonesome,

as if they knew they could bear no fruit in the cool climate of Japan. Its stalks

were long and fresh- looking, yet they were of no practical use.

The teacher lived all alone in the hut. On nights when he had no visitor, he would sit quietly and listen to the wind blowing through the banana leaves. The lonely atmosphere would deepen on rainy nights. Rainwater leaking through the roof dripped intermittently into a basin. To the ears of the poet sitting in the dimly lighted room, the sound made a strange harmony with the rustling of the banana leaves outside.

A

banana plant in the autumn gale -

I listen to the dripping of rain

Into

a basin at night.

The haiku seems to suggest the poet's awareness of his spiritual affinity with the banana plant.

Some people who visited this teacher of poetry may have noticed the affinity. Others may have seen the banana plant as nothing more than a convenient landmark. At any rate, they came to call the residence the Basho ("banana plant) Hut, and the name was soon applied to its resident, too: the teacher came to be known as the Master of the Basho Hut, or Master Basho. It goes without saying that he was happy to accept the nickname. He used it for the rest of his life.

I. First Metamorphosis: From Wanderer to Poet

Little material is available to recreate Basho's life prior to his settlement in the Basho Hut. It is believed that he was born in 1644 at or near Ueno in Iga Province, about thirty miles southeast of Kyoto and two hundred miles west of Edo. He was called Kinsaku and several other names as a child; he had an elder brother and four sisters. His father, Matsuo Yozaemon, was probably a low-ranking samurai who farmed in peacetime. Little is known about his mother except that her parents were not natives of Ueno. The social status of the family, while respectable, was not of the kind that promised a bright future for young Basho if he were to follow an ordinary course of life.

Yet Basho's career began in an ordinary enough way. It is presumed that as a youngster he entered the service of a youthful master, Todo Yoshitada, a relative of the feudal lord ruling the province. Young Basho first served as a page or in some such capacity.1 His master, two years his senior, was apparently fond of Basho, and the two seem to have become fairly good companions as they grew older. Their strongest bond was the haikai, one of the favorite pastimes of sophisticated men of the day. Apparently Yoshitada had a liking for verse writing and even acquired a haikai name, Sengin. Whether or not the initial stimulation came from his master, Basho also developed a taste for writing haikai, using the pseudonym Sobo. The earliest poem by Basho preserved today was written in 1662. In 1664, two haiku by Basho and one by Yoshitada appeared in a verse anthology published in Kyoto. The following year Basho, Yoshitada, and three others joined together and composed a renku of one hundred verses. Basho contributed eighteen verses, his first remaining verses of this type.

Basho's life seems to have been peaceful so far, and he might for the rest of his life have been a satisfied, low-ranking samurai who spent his spare time verse writing. He had already come of age and had assumed a samurai's name, Matsuo Munefusa. But in the summer of 1666 a series of incidents completely changed the course of his life. Yoshitada suddenly died a premature death. His younger brother succeeded him as the head of the clan and also as the husband of his widow. It is believed that Basho left his native home and embarked on a wandering life shortly afterward.

Various surmises have been made as to the reasons for Basho's decision to leave home, a decision that meant forsaking his samurai status. One reason which can be easily imagined is Basho's deep grief at the death of his master, to whom he had been especially close. One early biography even has it that he thought of killing himself to accompany his master in the world beyond, but this was forbidden by the current law against self- immolation. Another and more convincing reason is that Basho became extremely pessimistic about his future under the new master, whom he had never served before. As Yoshitada had Basho, the new master must have had around him favored companions with whom he had been brought up. They may have tried to prevent Basho from joining their circle, or even if they did not, Basho could have sensed some vague animosity in their attitudes toward him. Whatever the truth may have been, there seems to be no doubt that Basho's future as a samurai became exceedingly clouded upon the sudden death of his master.

Other surmises about Basho's decision to leave home have to do with his love affairs. Several early biographies claim that he had an affair with his elder brother's wife, with one of Yoshitada's waiting ladies, or with Yoshitada's wife herself. These are most likely the fabrications of biographers who felt the need for some sensational incident in the famous poet's youth. But there is one theory that may contain some truth. It maintains that Basho had a secret mistress, who later became a nun called Jutei. She may even have had a child, or several children, by Basho. At any rate, these accounts seem to point toward one fact: Basho still in his early twenties, experienced his share of the joys and griefs that most young men go through at one time or another.

Basho's life for the next few years is very obscure. It has traditionally been held that he went to Kyoto, then the capital of Japan, where he studied philosophy, poetry and calligraphy under well-known experts. It is not likely, however, that he was in Kyoto all during this time; he must often have returned to his hometown for lengthy visits. It might even be that he still lived in Ueno or in that vicinity and made occasional trips to Kyoto. In all likelihood he was not yet determined to become a poet at this time. Later in his own writing he was to recall "At one time I coveted an official post with a tenure of land." He was still young and ambitious, confident of his potential. He must have wished, above all, to get a good education that would secure him some kind of respectable position later on. Perhaps he wanted to see the wide world outside his native town and to mix with a wide variety of people. With the curiosity of youth he may have tried to do all sorts of things fashionable among the young libertines of the day. Afterward, he even wrote, "There was a time when I was fascinated with the ways of homosexual love."

One indisputable fact is that Basho had not lost his interest in verse writing. A haikai anthology published in 1667 contained as many as thirty- one of his verses, and his work was included in three other anthologies compiled between 1669 and 1671. His name was gradually becoming known to a limited number of poets in the capital. That must have earned him considerable respect from the poets in his hometown too. Thus when Basho made his first attempt to compile a book of haikai, about thirty poets were willing to contribute verses to it. The book, called The Seashell Game (Kai Oi), was dedicated to a shrine in Ueno early in 1672.

The Seashell Game represents a haiku contest in thirty rounds. Pairs of haiku, each one composed by a different poet, are matched and judged by Basho. Although he himself contributed two haiku to the contest, the main value of the book lies in his critical comments and the way he refereed the matches. On the whole, the book reveals hi to be a man of brilliant wit and colorful imagination, who had a good knowledge of popular songs, fashionable expressions, and the new ways of the world in general. It appears he compiled the book in a lighthearted mood, but his poetic talent was evident.

Then, probably in the spring of 1672, Basho set out on a journey to Edo, apparently with no intention of returning in the immediate future. On parting he sent a haiku to one of his friends in Ueno:

Clouds will separate

The two friends, after migrating

Wild goose's departure.

His motive for going to Edo cannot be ascertained. Now that he had some education, he perhaps wanted to find a promising post in Edo, then a fast- expanding city which offered a number of career opportunities. Or perhaps, encouraged by the good reception that The Seashell Game enjoyed locally, he had already made up his mind to become a professional poet and wanted his name known in Edo, too. Most likely Basho had multiple motives, being yet a young man with plenty of ambition. Whether he wanted to be a government official or a haikai master, Edo seemed to be an easier place than Kyoto to realize his dreams. He was anxious to try out his potential in a different, freer environment.

Basho's life for the next eight years is somewhat obscure again. It is said that in his early days in Edo he stayed at the home of one or another of his patrons. That is perhaps true, but it is doubtful that he could remain a dependent for long. Various theories, none of them with convincing evidence, argue that he became a physician's assistant, a town clerk, or a poet's scribe. The theory generally considered to be the closest to the truth is that for some time he was employed by the local waterworks department. Whatever the truth, his early years in Edo were not easy. He was probably recalling those days when he later wrote: "At one time I was weary of verse writing and wanted to give it up, and at another time I was determined to be a poet until I could establish a proud name over others. the alternatives battled in my mind and made my life restless."

Though he may have been in a dilemma Basho continued to write verses in the new city. In the summer of 1675 he was one of several writers who joined a distinguished poet of the time in composing a renku of one hundred verses; Basho, now using the pseudonym Tosei, contributed eight. The following spring he and another poet wrote two renku, each consisting of one hundred verses.. After a brief visit to his native town later in the year, he began devoting more and more time to verse writing. He must have made up his mind to become a professional poet around this time, if he had not done so earlier. His work began appearing in various anthologies more and more frequently, indicating his increasing renown. When the New Year came he apparently distributed a small book of verses among his acquaintances, a practice permitted only to a recognized haikai master. In the winter of that year he judged two haiku contests, and when they were published as Haiku Contests in Eighteen Rounds (Juhachiban Hokku Awase), he wrote a commentary on each match. In the summer of 1680 The Best Poems of Tosei's Twenty Disciples (Tosei Montei Dokugin Nijikkasen) appeared, which suggests that Basho already had a sizeable group of talented students. Later in the same year two of his leading disciples matched their own verses in two contests, "The rustic haiku Contest" ("Inaka no Kuawase") and "The Evergreen haiku Contest" ("Tokiwaya no Kuawase"), and Basho served as the judge. that winter his students built a small house in a quiet, rustic part of Edo and presented it to their teacher. Several months later a banana tree was planted in the yard, giving the hut its famous name. Basho, firmly established as a poet, now had his own home for the first time in his life.

II. Second Metamorphosis: From Poet to Wanderer

Basho was thankful to have a permanent home, but he was not to be cozily settled there. With all his increasing poetic fame and material comfort, he seemed to become more dissatisfied with himself. In his early days of struggle he had had a concrete aim in life, a purpose to strive for. That aim, now virtually attained, did not seem to be worthy of all his effort. He had many friends, disciples, and patrons, and yet he was lonelier than ever. One of the first verses he wrote after moving into the Basho Hut was:

Against the brushwood gate

Dead tea leaves swirl

In the stormy wind.

Many other poems written at this time, including the haiku about the banana tree, also have pensive overtones. In a headnote to one of them he even wrote: "I feel lonely as I gaze at the moon, I feel lonely as I think about myself, and I feel lonely as I ponder upon this wretched life of mine. I want to cry out that I am lonely, but no one asks me how I feel."

It was probably out of such spiritual ambivalence that Basho began practicing Zen meditation under Priest Butcho (1642-1715), who happened to be staying near his home. He must have been zealous and resolute in this attempt, for he was later to recall: "...and yet at another time I was anxious to confine myself within the walls of a monastery." Loneliness, melancholy, disillusion, ennui - whatever his problem may have been, his suffering was real.

A couple of events that occurred in the following two years further increased his suffering. In the winter of 1682 the Basho Hut was destroyed in a fire that swept through the whole neighborhood. He was homeless again, and probably the idea that man is eternally homeless began haunting his mind more and more frequently. A few months later he received news from his family home that his mother had died. Since his father had died already in 1656, he was now not only without a home but without a parent to return to.

As far as poetic fame was concerned, Basho and his disciples were thriving. In the summer of 1683 they published Shriveled Chestnuts (Minashiguri), an anthology of haikai verses which in its stern rejection of crudity and vulgarity in theme and in its highly articulate, Chinese-flavored diction, set them distinctly apart from other poets. In that winter, when the homeless Basho returned from a stay in Kai Province, his friends and disciples again gathered together and presented him with a new Basho Hut. He was pleased, but it was not enough to do away with his melancholy. His poem on entering the new hut was:

The sound of hail -

I am the same as before

Like that aging oak.

Neither poetic success nor the security of a home seemed to offer him much consolation. He was already a wanderer in spirit, and he had to follow that impulse in actual life.

Thus in the fall of 1684 Basho set out on his first significant journey. He had made journeys before, but not for the sake of spiritual and poetic discipline. Through the journey he wanted, among other things, to face death and thereby to help temper his mind and his poetry. He called it "the journey of a weather-beaten skeleton," meaning that he was prepared to perish alone and leave his corpse to the mercies of the wilderness if that was his destiny. If this seems to us a bit extreme, we should remember that Basho was of a delicate constitution and suffered from several chronic diseases, and that his travel in seventeenth-century Japan was immensely more hazardous than it is today.

It was a long journey, taking him to a dozen provinces that lay between Edo and Kyoto. From Edo he went westward along a main road that more or less followed the Pacific coastline. He passed by the foot of Mount Fuji, crossed several large rivers and visited the Grand Shinto Shrines in Ise. He then arrived at his native town, Ueno, and was reunited with his relatives and friends. His elder brother opened a memento bag and showed him a small tuft of gray hair from the head of his late mother.

Should I hold it in my hand

It would melt in my burning tears -

Autumnal

frost.

This is one of the rare cases in which a poem bares his emotion, no doubt because the grief he felt was uncontrollably intense.

After only a few days' sojourn in Ueno, Basho traveled farther on, now visiting a temple among the mountains, now composing verses with local poets. It was at this time that The Winter Sun (Fuyu no Hi), a collection of five renku which with their less pedantic vocabulary and more lyrical tone marked the beginning of Basho's mature poetic style, was produced. He then celebrated the New Year at his native town for the first time in years. He spent some more time visiting Nara and Kyoto, and when he finally returned to Edo it was already the summer of 1685.

The journey was a rewarding one. Basho met numerous friends, old and new, on the way. He produced a number of haiku and renku on his experiences during the journey, including those collected in The Winter Sun. He wrote his first travel journal, The Records of a Weather-Exposed Skeleton (Nozarashi Kiko), too. Through all these experiences, Basho was gradually changing. In the latter part of the journal there appears, for instance, the following haiku which he wrote at the year's end:

Another year is gone -

A travel hat on my head,

Straw sandals on my feet.

The poem seems to show Basho at ease in travel. The uneasiness that made him assume a strained attitude toward the journey disappeared as his trip progressed. He could not look at his wandering self more objectively, without heroism or sentimentalism.

He spent the next two years enjoying a quiet life at the Basho Hut. It was a modest but leisurely existence, and he could afford to call himself "an idle old man." He contemplated the beauty of nature as it changed with the seasons and wrote verses whenever he was inspired to do so. Friends and disciples who visited him shared his taste, and they often gathered to enjoy the beauty of the moon, the snow, or the blossoms. The following composition, a short prose piece written in the winter of 1686, seems typical of his life at this time:

A

man named Sora has his temporary residence near my hut, so I often drop in at

his place, and he at mine. When I cook something to eat, he helps to feed the

fire, and when I make tea at night, he comes over for company. A quiet, leisurely

person, he has become a most congenial friend of mine. One evening after a snowfall,

he dropped in for a visit, whereupon I composed a haiku:

Will you start

a fire?

I'll show you something nice -

A huge snowball.

The fire in the poem is to boil water for tea. Sora would prepare tea in the kitchen, while Basho, returning to the pleasures of a little boy, would make a big snowball in the yard. When the tea was ready, they would sit down and sip it together, humorously enjoying the view of the snowball outside. The poem, an unusually cheerful one for Basho, seems to suggest his relaxed, carefree frame of mind of those years.

The same sort of casual poetic mood led Basho to undertake a short trip to Kashima, a town about fifty miles east of Edo and well known for its Shinto shrine, to see the harvest moon. Sora and a certain Zen monk accompanied him in the trip in the autumn of 1687. Unfortunately it rained on the night of the full moon, and they only had a few glimpses of the moon toward dawn. Basho, however, took advantage of the chance to visit his former Zen master, Priest Butcho, who had retired to Kashima. The trip resulted in another of Basho's travel journals, A Visit to the Kashima Shrine (Kashima Kiko).

Then, just two months later, Basho set out on another long westward journey. He was far more at ease as he took leave than he had been at the outset of his first such journey three years earlier. He was a famous poet now, with a large circle of friends and disciples. They gave him many farewell presents, invited him to picnics and dinners, and arranged several verse-writing parties in his honor. Those who could not attend sent their poems. These verses, totaling nearly three hundred and fifty, were later collected and published under the title Farewell Verses (Kusenbetsu). there were so many festivities that to Basho "the occasion looked like some dignitary's departure - very imposing indeed."

He followed roughly the same route as on his journey of 1684, again visiting friends and writing verses here and there on the way. He reached Ueno at the year's end and was heartily welcomed as a leading poet in Edo. Even the young head of his former master's family, whose service he had left in his youth, invited him for a visit. In the garden a cherry tree which Yoshitada had loved was in full bloom:

Myriads of things past

Are brought to my mind -

These cherry blossoms!

In the middle of the spring Basho left Ueno, accompanied by one of his students, going first to Mount Yoshino to see the famous cherry blossoms. He traveled to Wakanoura to enjoy the spring scenes of the Pacific coast, and then came to Nara at the time of fresh green leaves. On he went to Osaka, and then to Suma and Akashi on the coast of Seto Inland Sea, two famous places which often appeared in old Japanese classics.

From Akashi Basho turned back to the east, and by way of Kyoto arrived at Nagoya in midsummer. After resting there for awhile, he headed for the mountains of central Honshu, an area now popularly known as the Japanese Alps. An old friend of his and a servant, loaned to him by someone who worried about the steep roads ahead accompanied Basho. His immediate purpose was to see the harvest moon in the rustic Sarashina district. As expected, the trip was a rugged one, but he did see the full moon at that place celebrated in Japanese literature. He then traveled eastward among the mountains and returned to Edo in late autumn after nearly a year of traveling.

This was probably the happiest of all Basho's journeys. He had been familiar with the route much of the way, and where he had not, a friend and a servant had been there to help him. His fame as a poet was fairly widespread, and people he met on the way always treated him with courtesy. It was a productive journey, too. In addition to a number of haiku and renku, he wrote two journals: The Records of a Travel-Worn Satchel (Oi no Kobumi), which covers his travel from Edo to Akashi, and A Visit to Sarashina Village (Sarashina Kiko), which focuses on his moon viewing trip to Sarashina. The former has an especially significant place in the Basho canon, including among other things a passage that declares the haikai to be among the major forms of Japanese art. He was now clearly aware of the significance of haikai writing; he was confident that the haikai, as a serious form of art, could point toward an invaluable way of life.

It was no wonder, then, that Basho began preparing for the next journey almost immediately. As he described it, it was almost as if the God of Travel were beckoning him. Obsessed with the charms of the traveler's life, he now wanted to go beyond his previous journeys; he wanted to be a truer wanderer than ever before. In a letter written around this time, he says he admired the life of a monk who wanders about with only a begging bowl in his hand. Basho now wanted to travel, not as a renowned poet, but as a self-disciplining monk. Thus in the pilgrimage to come he decided to visit the northern part of Honshu, a mostly rustic and in places even wild region where he had never been and had hardly an acquaintance. He was to cover about fifteen hundred miles on the way. Of course it was going to be the longest journey of his life.

Accompanied by Sora, Basho left Edo in the late spring of 1689. Probably because of his more stern and ascetic attitude toward the journey, farewell festivities were fewer and quieter this time. He proceeded northward along the main road stopping at places of interest such as the Tosho Shrine at Nikko, the hot spa at Nasu, and an historic castle site at Iizuka. When he came close to the Pacific coast near Sendai he admired the scenic beauty of Matsushima. From Hiraizumi, a town well known as the site of a medieval battle, Basho turned west and reached the coast of the Sea of Japan at Sakata. After a short trip to Kisagata in the north, he turned southwest and followed the main road along the coast. It was from this coast that he saw the island of Sado in the distance and wrote one of his most celebrated poems:

The rough sea -

Extending toward Sado Isle,

The Milky Way.

Because of the rains, the heat, and the rugged road, this part of the journey was very hard for Basho and Sora, and they were both exhausted when he finally arrived at Kanazawa. They rested at the famous hot spring at Yamanaka for a few days, but Sora, apparently because of prolonged ill- health, decided to give up the journey and left his master there. Basho continued alone until he reached Fukui. There he met an old acquaintance who accompanied him as far as Tsuruga, where another old friend had come to meet Basho, and the two traveled south until they arrived at Ogaki, a town Basho knew well. A number of Basho's friends and disciples were there, and the long journey through unfamiliar areas was finally over. One hundred and fifty-six days had passed since he left Edo.

The travel marked a climax in Basho's literary career. He wrote some of his finest haiku during the journey. The resulting journal The Narrow Road to the Deep North (Oku no Hosomichi), is one of the highest attainments in the history of poetic diaries in Japan. His literary achievement was no doubt a result of his deepening maturity as a man. He had come to perceive a mode of life by which to resolve some deep dilemmas and to gain peace of mind. It was based on the idea of sabi, the concept that one attains perfect spiritual serenity by immersing oneself in the egoless, impersonal life of nature. The complete absorption of one's petty ego into the vast, powerful, magnificent universe - this was the underlying theme of many poems by Basho at this time, including the haiku on the Milky Way we have just seen. This momentary identification of man with inanimate nature was, in his view, essential to poetic creation. Though he never wrote a treatise on the subject, there is no doubt that Basho conceived some unique ideas about poetry in his later years. Apparently it was during this journey that he began thinking about poetry n more serious, philosophical terms. The two earliest books known to record Basho's thoughts on poetry, Records of the Seven Days (Kikigaki Nanukagusa) and Conversations at Yamanaka (Yamanaka Mondo), resulted from it.

Basho spent the next two years visiting his old friends and disciples in Ueno, Kyoto, and towns on the southern coast of Lake Biwa. With one or another of them he often paid a brief visit to other places such as Ise and Nara. Of numerous houses he stayed at during this period Basho seems to have especially enjoyed two: the Unreal Hut and the House of Fallen Persimmons, as they were called. The Unreal Hut, located in the woods off the southernmost tip of lake Biwa, was a quiet, hidden place where Basho rested from early summer to mid-autumn in 1690. He thoroughly enjoyed the idle, secluded life there, and described it in a short but superb piece of prose. Here is one of the passages:

In

the daytime an old watchman from the local shrine or some villager from the foot

of the hill comes along and chats with me about things I rarely hear of, such

as a wild boar's looting the rice paddies or a hare's haunting the bean farms.

When the sun sets under the edge of the hill and night falls, I quietly sit and

wait for the moon. With the moonrise I begin roaming about, casting my shadow

on the ground.

When the night deepens, I return to the hut and meditate on

right and wrong, gazing at the dim margin of a shadow in the lamplight.

Basho had another chance to live a similarly secluded life later at the House of the Fallen Persimmons in Saga, a northwestern suburb of Kyoto. The house, owned by one of his disciples, Mukai Kyorai (1651-1704), was so called because persimmon trees grew around it. There were also a number of bamboo groves, which provided the setting for a well-known poem by Basho:

The cuckoo -

Through the dense bamboo grove,

Moonlight seeping.

Basho stayed at this house for seventeen days in the summer of 1691. The sojourn resulted in The Saga Diary (Saga Nikki), the last of his longer prose works.

All during this period at the two hideaways and elsewhere in the Kyoto-Lake Biwa area, Basho was visited by many people who shared his interest in poetry. Especially close to him were two of his leading disciples, Kyorai and Nozawa Boncho (16?-1714), partly because they were compiling a haikai anthology under Basho's guidance. The anthology, entitled The Monkey's Raincoat (Sarumino) and published in the early summer of 1691 represented a peak in haikai of the Basho style. Basho's idea of sabi and other principles of verse writing that evolved during his journey to the far north were clearly there. Through actual example the new anthology showed that the haikai could be a serious art form capable of embodying mature comments on man and his environment.

Basho returned to Edo in the winter of 1691. His friends and disciples there, who had not seen him for more than two years, welcomed him warmly. for the third time they combined their efforts to build a hut for their master, who had given up the old one just before his latest journey. In this third Basho Hut, however, he could not enjoy the peaceful life he desired. For one thing, he now had a few people to look after. An invalid nephew had come to live with Basho, who took care of him until his death in the spring of 1693. A woman by the name of Jutei, with whom Basho apparently had had some special relationship in his youth, also seems to have come under his care at this time. She too was in poor health, and had several young children besides. Even apart from these involvements, Basho was becoming extremely busy, no doubt due to his great fame as a poet. many people wanted to visit him, or invited him for visits. for instance, in a letter presumed to have been written on the eighth of the twelfth month, 1693, he told one prospective visitor that he would not be home on the ninth, tenth, eleventh, twelfth, fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth, suggesting that the visitor come either on the thirteenth or the eighteenth.3 In another letter written about the same time, he bluntly said: "Disturbed by others, Have no peace of mind." That New Year he composed this haiku:

Year after year

On the monkey's face

A monkey's mask.

The poem has a touch of bitterness unusual for Basho. He was dissatisfied with the progress that he (and possibly some of his students) was making.

As these responsibilities pressed on him, Basho gradually became somewhat nihilistic. He had become a poet in order to transcend worldly involvements, but now he found himself deeply involved in worldly affairs precisely because of his poetic fame. The solution was either to renounce being a poet or to stop seeing people altogether. Basho first tried the former, but to no avail. "I have tried to give up poetry and remain silent," he said, "but every time I did so a poetic sentiment would solicit my heart and something would flicker in my mind. Such is the magic spell of poetry." He had become too much of a poet. Thus he had to resort to the second alternative: to stop seeing people altogether. This he did in the autumn of 1693, declaring:

Whenever

people come, there is useless talk. Whenever I go, and visit, I have the unpleasant

feeling of interfering with other men's business. Now I can do nothing better

than follow the examples of Sun Ching and Tu Wu-lang,4 who confined themselves

within locked doors. Friendlessness will become my friend, and poverty my wealth.

A stubborn man at fifty years of age, I thus write to discipline myself.

The morning-glory -

In the daytime, a bolt is fastened

On the frontyard

gate.

Obviously,

Basho wished to admire the beauty of the morning-glory without having to keep

a bolt on his gate. How to manage to do this must have been the subject of many

hours of meditation within the locked house. He solved the problem, at least to

his own satisfaction, and reopened the gate about a month after closing it.

Basho's solution was based on the principle of "lightness," a dialectic

transcendence of sabi. Sabi urges man to detach himself from worldly involvements;

"lightness" makes it possible for him, after attaining that detachment,

to return to the mundane world. man lives amid the mire as a spiritual bystander.

He does not escape the grievances of living; standing apart, he just smiles them

away. Basho began writing under this principle and advised his students to emulate

him. The effort later came to fruition in several haikai anthologies, such as

A Sack of Charcoal (Sumidawara), The Detached Room (Betsuzashiki) and The Monkey's

Cloak, Continued (Zoku Sarumino). Characteristic verses in these collections reject

sentimentalism and take a calm, carefree attitude to the things of daily life.

they often exude lighthearted humor.

Having thus restored his mental equilibrium, Basho began thinking about another journey. He may have been anxious to carry his new poetic principle, "lightness," to poets outside of Edo, too. Thus in the summer of 1694 he traveled westward on the familiar road along the Pacific coast, taking with him one of Jutei's children, Jirobei. He rested at Ueno for a while, and then visited his students in Kyoto and in town near the southern coast of Lake Biwa. Jutei, who had been struggling against ill health at the Basho Hut, died at this time and Jirobei temporarily returned to Edo. Much saddened, Basho went back to Ueno in early autumn for about a month's rest. He then left for Osaka with a few friends and relatives including his elder brother's son Mataemon as well as Jirobei. But Basho's health was rapidly failing, even though he continued to write some excellent verses. One of his haiku in Osaka was:

This autumn

Why am I aging so?

Flying towards the clouds, a bird.

The poem indicates Basho's awareness of approaching death. Shortly afterward he took to his bed with a stomach ailment, from which he was not to recover. Numerous disciples hurried to Osaka and gathered at his bedside. He seems to have remained calm in his last days. He scribbled a deathbed note to his elder brother, which in part read: "I am sorry to have to leave you now. I hope you will live a happy life under Mataemon's care and reach a ripe old age. There is nothing more I have to say." The only thing that disturbed his mind was poetry. According to a disciple's record, Basho fully knew that it was time for prayers, not for verse writing, and yet he thought of the latter day and night. Poetry was now an obsession - "a sinful attachment," as he himself called it. His last poem was:

On a journey, ailing -

My dreams roam about

Over a withered moor.

----------------------------------------

Spring

rain

conveyed under the trees

in drops.

A

green willow,

dripping down into the mud,

at low tide.

By

the old temple,

peach blossoms;

a man treading rice.

With

every gust of wind,

the butterfly changes its place

on the willow.

All

the day long-

yet not long enough for the skylark,

singing, singing.

Husking

rice,

a child squints up

to view the moon.

Cedar

umbrellas, off

to Mount Yoshimo for

the cherry blossoms.

Octopus

traps -

summer’s moonspun dreams,

soon ended.

Winter

downpour -

even the monkey

needs a raincoat

Year’s

end, all

corners of this

floating world, swept.

----------------------------------------

BASHÔ

(1644-1694)

tr. by Kenneth Rexroth

Autumn

evening —

A crow on a bare branch.

An

old pond —

The sound

Of a diving frog.

On

this road

No one will follow me

In the Autumn evening.

Summer

grass

Where warriors dream.

The

tree from whose flower

This perfume comes

Is unknowable.

------------------------------------------

Basho

Poete

et religieux, né dans la province d’Iga, dans une famille de samurai.

En 1666, il se sépara de son clan, pour une raison encore inconnue, et

se rendit a Kyoto ou il étudia l’art du haiku et du waka sous la direction

de Kitamura Kigin (1624 - 1705), et les classiques chinois sous celle d’Itô

Tan’an . Ayant gagné Edo en 1672, il s’y adonna a la peinture

et a la composition du haiku, art poétique dans lequel il acquit une maîtrise

inégalée, melant le sens du rythme de la poésie chinoise

au réalisme japonais. Son ermitage possédant un bananier (bashô),

ce fut sous ce nom qu’il devint célebre. De nombreux disciples virent

alors aupres de lui pour s’instruire. Religieux zen sans appartenance particuliere,

Bashô mena a partir de 1684, une vie errante, rapportant de chacune de ses

randonnées un " journal " : Nozaraki-kikô (1685), Kashima-kikô

(1687), Sarashina-kikô (1688), Oku no Hosomichi (Route étroite vers

le Nord, 1689), Genjuan-ki (1690), Saga-nikki (1691), Oi no Kobumi etc. Tout d’abord

influencé par les écoles Kofu et Danrin, il créa ensuite

son propre style et publia plusieurs recueils de ses haikus : Minashiguri (1683),

Fuyu no Hi (Lumieres d’Hiver, 1684), Haru no Hi (Lumieres de printemps, 1984),

Arano (1689), Hisago (1691), Sumidawara (1694), ect ; dans lesquels, en notations

rapides et rythmées, en seulement 17 syllabes, il évoque ou suggere

une atmosphere, un état d’âme, la beauté inhérente

aux choses et aux etres, sentiments basés sur le sens du sabi (simplicité),

du shiori (suggestion), du hosomi (l’amour des petites choses) et du karumi

ou sens de l’humour. Son style est appelé shôfu. Bashô

mourut a Osaka dans la maison de la poétesse Sono Jo. Ses disciples sont

appelés les Bashô Juttestu.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Genjuan

no ki (The Hut of the Phantom Dwelling)

by Matsuo Basho

1690

Beyond Ishiyama, with its back to Mount Iwama, is a hill called Kokub-uyama-the name I think derives from a kokubunji or government temple of long ago. If you cross the narrow stream that runs at the foot and climb the slope for three turnings of the road, some two hundred paces each, you come to a shrine of the god Hachiman. The object of worship is a statue of the Buddha Amida. This is the sort of thing that is greatly abhorred by the Yuiitsu school, though I regard it as admirable that, as the Ryobu assert, the Buddhas should dim their light and mingle with the dust in order to benefit the world. Ordinarily, few worshippers visit the shrine and it's very solemn and still. Beside it is an abandoned hut with a rush door. Brambles and bamboo grass overgrow the eaves, the roof leaks, the plaster has fallen from the walls, and foxes and badgers make their den there. It is called the Genjuan or Hut of the Phantom Dwelling. The owner was a monk, an uncle of the warrior Suganuma Kyokusui. It has been eight years since he lived there-nothing remains of him now but his name, Elder of the Phantom Dwelling.

I too gave up city life some ten years ago, and now I'm approaching fifty. I'm like a bagworm that's lost its bag, a snail without its shell. I've tanned my face in the hot sun of Kisakata in Ou, and bruised my heels on the rough beaches of the northern sea, where tall dunes make walking so hard. And now this year here I am drifting by the waves of Lake Biwa. The grebe attaches its floating nest to a single strand of reed, counting on the reed to keep it from washing away in the current. With a similar thought, I mended the thatch on the eaves of the hut, patched up the gaps in the fence, and at the beginning of the fourth month, the first month of summer, moved in for what I thought would be no more than a brief stay. Now, though, I'm beginning to wonder if I'll ever want to leave.

Spring is over, but I can tell it hasn't been gone for long. Azaleas continue in bloom, wild wisteria hangs from the pine trees, and a cuckoo now and then passes by. I even have greetings from the jays, and woodpeckers that peck at things, though I don't really mind-in fact, I rather enjoy them. I feel as though my spirit had raced off to China to view the scenery in Wu or Chu, or as though I were standing beside the lovely Xiao and Xiang rivers or Lake Dongting. The mountain rises behind me to the southwest and the nearest houses are a good distance away. Fragrant southern breezes blow down from the mountain tops, and north winds, dampened by the lake, are cool. I have Mount Hie and the tall peak of Hira, and this side of them the pines of Karasaki veiled in mist, as well as a castle, a bridge, and boats fishing on the lake. I hear the voice of the woodsman making his way to Mount Kasatori, and the songs of the seedling planters in the little rice paddies at the foot of the hill. Fireflies weave through the air in the dusk of evening, clapper rails tap out their notes-there's surely no lack of beautiful scenes. Among them is Mikamiyama, which is shaped rather like Mount Fuji and reminds me of my old house in Musashino, while Mount Tanakami sets me to counting all the poets of ancient times who are associated with it. Other mountains include Bamboo Grass Crest, Thousand Yard Summit, and Skirt Waist. There's Black Ford village, where the foliage is so dense and dark, and the men who tend their fish weirs, looking exactly as they're described in the Man'yoshu. In order to get a better view all around, I've climbed up on the height behind my hut, rigged a platform among the pines, and furnished it with a round straw mat. I call it the Monkey's Perch. I'm not in a class with those Chinese eccentrics Xu Quan, who made himself a nest up in a cherry-apple tree where he could do his drinking, or Old Man Wang, who built his retreat on Secretary Peak. I'm just a mountain dweller, sleepy by nature, who has turned his footsteps to the steep slopes and sits here in the empty hills catching lice and smashing them.

Sometimes, when I'm in an energetic mood, I draw clear water from the valley and cook myself a meal. I have only the drip drip of the spring to relieve my loneliness, but with my one little stove, things are anything but cluttered. The man who lived here before was truly lofty in mind and did not bother with any elaborate construction. Outside of the one room where the Buddha image is kept, there is only a little place designed to store bedding.

An eminent monk of Mount Kora in Tsukushi, the son of a certain Kai of the Kamo Shrine, recently journeyed to Kyoto, and I got someone to ask him if he would write a plaque for me. He readily agreed, dipped his brush, and wrote the three characters Gen-ju-an. He sent me the plaque, and I keep it as a memorial of my grass hut. Mountain home, traveler's rest-call it what you will, it's hardly the kind of place where you need any great store of belongings. A cypress bark hat from Kiso, a sedge rain cape from Koshi-that's all that hang on the post above my pillow. In the daytime, I'm once in a while diverted by people who stop to visit. The old man who takes care of the shrine or the men from the village come and tell me about the wild boar who's been eating the rice plants, the rabbits that are getting at the bean patches, tales of farm matters that are all quite new to me. And when the sun has begun to sink behind the rim of the hills, I sit quietly in the evening waiting for the moon so I may have my shadow for company, or light a lamp and discuss right and wrong with my silhouette.

But when all has been said, I'm not really the kind who is so completely enamored

of solitude that he must hide every trace of himself away in the mountains and

wilds. It's just that, troubled by frequent illness and weary of dealing with

people, I've come to dislike society. Again and again I think of the mistakes

I've made in my clumsiness over the course of the years. There was a time when

I envied those who had government offices or impressive domains, and on another

occasion I considered entering the precincts of the Buddha and the teaching rooms

of the patriarchs. Instead, I've worn out my body in journeys that are as aimless

as the winds and clouds, and expended my feelings on flowers and birds. But somehow

I've been able to make a living this way, and so in the end, unskilled and talentless

as I am, I give myself wholly to this one concern, poetry. Bo Juyi worked so hard

at it that he almost ruined his five vital organs, and Du Fu grew lean and emaciated

because of it. As far as intelligence or the quality of our writings go, I can

never compare to such men. And yet we all in the end live, do we not, in a phantom

dwelling? But enough of that-I'm off to bed.

---------------------------------------------------Among these summer trees,

a pasania-

something to count on

Castle

Matsuo

Kinsaku—the future Basho—was born in 1644 in Ueno, the capital of Iga Province.

His father was a samurai who, in an era of peace, had taken to farming. Looming

over the town was Ueno Castle, from which Lord Todo governed the province. It

was to this castle that Matsuo was sent, at the age of nine, to serve as a page.

He was assigned to a son of Todo, elevenyearold Yoshitada.

Matsuo became Yoshitada’s

companion and studymate; and the two were soon fast friends. Together they learned

their ideographs—roamed the corridors of the castle— sported in the surrounding

hills. Entering adolescence, the boys found themselves drawn more to literary

than to martial arts; and a poet named Kigin was brought in from Kyoto to tutor

them.

They took to poetry with a passion, dashing off haiku after haiku and

even adopting pennames (Sobo and Sengin). Kigin was pleased with their efforts,

and secured publication— in an anthology issued in Kyoto—of several of their haiku.*

* A haiku is a formal poem of seventeen syllables. Until Basho infused it with a new spirit, the form was little more than a vehicle for wordplay and wit.

So

Matsuo and Yoshitada grew into manhood together. Even after Yoshitada married,

they remained close friends and continued to trade poems. For both the future

seemed bright. Yoshitada was to succeed his father as governor of the province;

and Matsuo could look forward to a high position under him.

Yet each spring,