Terebess

Asia Online (TAO)

Index

Home

The Haiku of Yosa Buson

(与謝蕪村

1716-1784)

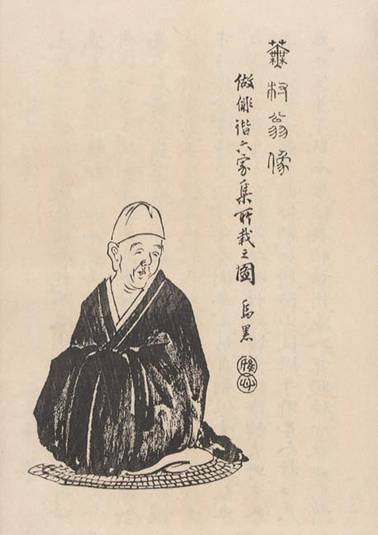

This is a portrait of Buson in 'Buson Poems: Annotated Edition'.

In Japanese:

Buson Haikushuu

(DOC)

http://etext.virginia.edu/japanese/buson/haikushu/YosHaik.html

http://xtf.lib.virginia.edu/xtf/view?docId=Japanese/uvaGenText/tei/YosHaikT.xml

Buson's Haiku Illustrated by Himself (DOC)

(俳画 haiga, 句碑 kuhi, 短冊 tanzaku, 俳諧一枚摺 haikai ichimaizuri)

Haiku of Yosa Buson translated into English, French, Spanish (DOC), organized by Romaji, in alphabetical order

Buson's Haiku in Hungarian Translation, Japanese (+Romaji) - Hungarian bilingual version

Buson portrait by Keibun, from Haikai Buson Anthology; Collection of Sekkasha

"Buson produced 2,918 haiku poems, including 7 supplements and painted 124 haiga paintings and 577 Japanese style paintings in his life." (Shoji Kumano)

"Yosa Buson was an extremely prolific poet. Over 2,800 of his hokku are extant, as well as some 120 linked verse sequences, as well as numerous examples of haiga, three haishi - unconventional verses which are hybrid of haikai and Chinese poetry, and several kanshi (poems in Chinese)." (Cheryl A. Crowley)

"Buson, also

called Yosa Buson, original surname Taniguchi (born 1716, Kema, Settsu province,

Japan—died Jan. 17, 1784, Kyoto), Japanese painter of distinction but even

more renowned as one of the great haiku poets.

Buson came of a wealthy family but chose to leave it behind to pursue a career

in the arts. He traveled extensively in northeastern Japan and studied haiku

under several masters, among them Hayano Hajin, whom he eulogized in Hokuju

Rosen wo itonamu (1745; “Homage to Hokuju Rosen”). In 1751 he settled

in Kyoto as a professional painter, remaining there for most of his life. He

did, however, spend three years (1754–57) in Yosa, Tango province, a region

noted for its scenic beauty. There he worked intensively to improve his technique

in both poetry and painting. During this period he changed his surname from

Taniguchi to Yosa. Buson’s fame as a poet rose particularly after 1772.

He urged a revival of the tradition of his great predecessor Matsuo Basho but

never reached the level of humanistic understanding attained by Basho. Buson’s

poetry, perhaps reflecting his interest in painting, is ornate and sensuous,

rich in visual detail. “Use the colloquial language to transcend colloquialism,”

he urged, and he declared that in haiku “one must talk poetry.” To

Buson this required not only an accurate ear and an experienced eye but also

intimacy with Chinese and Japanese classics. Buson’s interest in Chinese

poetry is especially evident in three long poems that are irregular in form.

His experimental poems have been called “Chinese poems in Japanese,”

and two of them contain passages in Chinese."

Encyclopadia Britannica

Buson's Chronology

1716- Japanese

haiku master and painter Yosa Buson, or Yosa no Buson or Taniguchi

Buson was born at Kema in Settsu Province (now suburb of Osaka) and lost

parents at boyhood.

1737- he moved to Edo (now Tokyo) and learned poetry under the haikai master

Hayano Hajin.

1742- after the death of Hajin, he toured northern areas and visited western

Japan,

where he painted and practiced haikai.

1744- following

in the footsteps of Matsuo Basho, he traveled through the wilds of

northern Honshu and published his notes from the trip under the name Buson.

1751- settled in Kyoto and began to write under the name of Yosa. It is told

that he

took this name from his mother's birthplace (Yosa in the province of Tango).

1756- 1765- active as a painter and gradually returned to haiku. Poetry and

painting

affected each other in his art. He completed his own style of painting and was

using the names of Sha Cho-Koh, Shunsei (Spring Star) and others.

1760- married

at the age of 45 and had one daughter, Kuno.

1770- took the name of Yahantei (Midnight Hermitage) for his studio.

1771- painted a famous set of ten screens with his great contemporary Ike no

Taiga,

demonstrating his status as one of the finest painters of his time.

1772- poetry group that he formed published its first book. His haiku poems

show

a more objective, pictorial style than Basho's humane, wide-ranging work.

He became famous both as a poet of haikai (ancestor of modern haiku) and

haiga (haikai painting).

1776- his group built a Bashoan (Basho house) for gatherings.

1783-He died on December 25th and buried at Konpukuji in Kyoto.

------------------------------------------------------------

Who is Yosa Buson?

By Hiro Saga

Peony having scattered, two or three petals lie on one another.

[botan chirite uchi kasanari-nu nisan ben]translation by Hiro Saga

Buson (1716-84). Leading haiku poet of the late 18th century and, with Basho (1644-94) and Issa (1763-1827), one of the great names in haiku. Also known as Yosa Buson or Taniguchi Buson. Also a distinguished Bunjinga (literati-style) painter, he perfected haiga ("haiku sketch") as a branch of Japanese pictorial art. His best-known painting disciple, Matsumura Goshun, also known as Gekkei, founded the Shijo school.

Early Career: Born near Osaka, as a youth Buson went to Edo (now Tokyo). For five years (1737-42) he belonged to a haikai linked-verse circle over which Hayano Hajin (1676-1742) presided. Here he learned the traditions of the Basho school haikai as transmitted by Hattori Ransetsu and Takarai Kikaku. After Hajin's death Buson spent much time around Yuki, north of edo, where he painted, practiced haikai, and worte Hokuju Rosen wo itamu (Elegy to the old poet Hokuju), the first of his innovative poems that foreshadow modern free verse. Buson also visited places in northeastern Japan famed in Basho's poetic diary, Oku No Hosomichi (1694; tr The Narrow Road to the Deep North, 1966).

Buson settled in Kyoto in the late 1750s. He was active in Mochizuki Sooku's (1688-1766) poetry circle and was also actively painting in the Chinese-inspired bunjinga style. By practicing both poetry and painting, he aspired to the ideals of the bunjin (Ch: wen-ren or wen-jen; literati) of China. One of Buson's commissions involved collaborating with Ike No Taiga on a landscape series based on Chinese poems, Juben jugi (1771, Ten Conveniences and Ten Pleasures), now a National Treasure. In 1770 he took the name of Yahantei the Second (Midnight Hermitage) for his studio. His haikai teacher Hajin was the First Yahantei. In painting, he used the names of Sha Cho-Koh, Shunsei (Spring Star) and others during his earlier years in Kyoto.

Master of Poetry and Painting: Buson found his distinct voice partly from association with two dissimilar poets, Tan Taigi and Kuroyanagi Shoha (d 1772), both of whom helped him develop his spontaneous and sensual style. Following their passing, Buson emerged as the central figure of a haikai revival known as the "Return to Basho" movement. In 1776 his own poetry group built a clubhouse, the Bashoan (Basho Hut), for their haikai and linked-verse gatherings. Buson also prepared several illustrated scrolls and screens, including the text of Oku no hosomich, which helped canonize Basho as a grand saint of poetry. Although Buson sought to emulate Basho, his own poetry is clearly different and versatile. Buson read classics extensively and studied different styles of Chinese and Japanese paintings. Poetry and painting affected each other in his art. His poems were, diversely enough, rich in imagery, clearly depicting fine movements and sensual appearances of things, dynamic with wider landscapes, lyrical, sensitive to human affairs, romantic with hidden stories, graceful, and longingly time-conscious. Buson completed his own style of painting in his later years when he was using the name of Sha-In. Freed from the influence of China, he created genuine Japanese landscapes.

[This description is adapted from Japan: An Illustrated Enclyclopedia, p.150; 1993, Kodansha; Tokyo]

------------------------------------------------------------

Buson’s Two Candles by Anita Virgil

Too often, I have read that Buson's poetry derives from imagination. Usually, this is mentioned by critics who are comparing his work with that of Basho. The underlying derogatory implication -- for I take it that "fabrication" is meant when the word "imagination" is used -- has always annoyed me because it ignores the quantity of consistently fine poems produced by Buson containing strikingly subtle and exact images. Could it be that the sheer diversity of Buson's work has given rise to such a notion? Reality is the springboard for all artistic creation, no less for Basho than for Buson. But the idea of "imagined" poems does not truly reckon with the fact of Buson's urbanity nor with the vital time period in which he wrote -- a time when inroads had been made that liberalized the subject matter for literature. The arts of Ukiyo and the developing art of senryu were in place. And one must also consider Buson's enormous talent as a professional artist. Had I not been privileged to see the exhibition of Buson's art in the early 1970's in New York City's Asia House, I would probably never have realized the degree to which his poetry stems from his vision as an artist. It strikes me that criticism of Buson may have its foundations in the inability of the non-artist to recognize evidence of the very thing which sets the visual artist apart from others: his ability to see more than most people. Combine this with the gift of writing and you have Buson, a man whose poems are composed of the most acutely observed realities reflecting a broad life-experience.

Lighting one candle

With another candle;

An evening of spring. 1

From the first, this was one of my favorite Japanese haiku. Its fragility, elegance and equipoise are such that I have never felt a need to dissect it. But after experiencing Buson's paintings firsthand, it suddenly opened to me. It is a poem in which one beautiful thing literally fires another to a resultant sheer beauty. Surely, in the case of Buson, one must recognize how his artist's eye charges his writing dynamically, constantly.

The slow day;

A pheasant

Settles on the bridge. 2In the stillness

Between the arrival of guests

The peonies. 3Tilling the field:

The cloud that never moved

Is gone. 4The spring sea:

all day long

undulating, undulating. 5

Several influences must have produced such a talent as Buson. There is ample evidence that Basho was a major one. Not only did Buson study under a teacher who was a pupil of Basho's disciples, Kikaku and Ransetsu, but he continually, in his art, paid tribute to the Master. He painted portraits of Basho, illustrated Oku no Hosomichi, and Buson's crow paintings engender the very loneliness and isolation of autumn and winter echoing Basho's famous crow poem.

The delicacy and elegance of Onitsura's work also finds its way into Buson's poems. Buson was well acquainted with Onitsura's work—in fact, wrote an envoi to selections from Onitsura's poems in 1769.

How hot the cobwebs look

Hanging on summer trees! 6Onitsura (1660-1738)

Spiders' webs

Are hot things

In the summer grove. 7Buson (1716-1783)

The senryu, in addition to ridiculing the overly sentimental, poor caliber haiku written post-Basho, opened the way for use of highly sensual subject matter which, Harold G. Henderson says, a considerable number of Buson's haiku contain. Concurrent with Buson's flourishing is the bourgeois art of Ukiyo-e, "The Floating World." It incorporated all aspects of city life for its subject matter. Life in the Yoshiwara, the licensed quarter of prostitution in Edo, gave rise to the world-famous Japanese woodblock prints which were to influence the French Impressionist painters over 100 years later. When Buson was 48 years of age, Harunobu was producing intimate glimpses in his woodblock prints of lovely and sensuous women, and Utamaro, too, was working his magical print art during Buson's mature years. The new freedom of expression in all the arts had the effect of making this era an aesthetically fertile one. Two examples by Buson of this cross-fertilization:

Early morning frost --

From the brothels of Muro,

The scent of hot soup. 8

Over the gold screen

Whose silk gauze dress?

The autumn wind. 9

The following poem uses the same subject matter as Basho's poem from Oku no Hosomichi: courtesans. But how different the handling and attitudes!

Courtesans

Buying sashes in their room,

Plum blossoms blooming. 10Buson

Under the same roof

Courtesans, too, are asleep --

Bush clover and the moon. 11Basho (1689)

Buson's courtesans were elegant ladies whose work obliged them to purchase lavish clothing. In his poem, Buson uses a close-up view of these indentured women of the Yoshiwara who were kept in quasi-isolation from the world outside their windows where, in contrast, other "beauties" (the blossoming plum trees) are rooted in freedom, open to sun and air and moonlight. The courtesans, adorning themselves with gorgeous silks and brocades, create another kind of "blooming." It is this parallelism that lends surplus meaning and poetic overtones to the poem. Basho's principle of internal comparison is evident throughout Buson's poem.

Basho's poem shows us rural courtesans who may have stayed at the inn Basho and his traveling companion, Sora, visited. But Basho's poem has a different perspective. Like a long-shot in a film where the cameraman pulls back to give a panoramic view, it provides a broad view. There is total acceptance of life observed in his poem, a total equality among the elements which suffuse this poem with serenity. This world, as represented by the women and the clover, and the extraterrestrial world, the moon and space, are one. Hence, Basho's religious attitude in the broadest sense comes through to the reader. Buson's poem, however, brings us directly inside, and one shares this intimate moment with his courtesans. One does not observe them from afar. Without the least sentimentality, Buson still can pull from us the immense poignancy of this moment. These two poems illustrate clearly the different personalities of each great poet. One who, though participating in the world about him, maintains a certain distance; the other, who participates in the world and is not disturbed by contact with all aspects of it: Buson functions fully within the framework of his existence. Though there are critics who value the Buson poem less, I see both poems as great works -- different works. Buson makes this very point:

The two plum-trees:

I love their blooming,

One early, one later. 12

Another point repeated in literature on Buson is that he does not go into any discussion of linking man and nature as Basho does. Buson, who found in Basho a vital source of inspiration, could not help but be influenced by the Master's words on this subject. It is an obvious theme stressed in Basho's work. It is my feeling that Buson's poetry and his paintings repeatedly make it clear that he accepts this integration fully. Therefore there was no need for him to formulate it into a philosophy -- his medium is his message. Yet, in An Introduction to Haiku, Harold G. Henderson says: "Actually very little is known of Buson's philosophy, and outside of his poetry and painting he apparently never did formulate one. We do know that he must have enormously enjoyed the ever-changing aspects of the passing world, though more as an observer than by in any way identifying himself with them." 13 I find this statement incomprehensible and highly contradictory. Weighted as it is on the side of theorizing about art instead of recognizing that the kind of art one produces conveys one's philosophy, this comment was clearly made by an individual not directly involved in the creative process, literary or visual, by one who himself was more an observer than a consummate participant in the creative act. As a poet and an artist, I can say that one's creations stand as the most vivid and open exposure of one's attitudes and beliefs.

With his innate sense of elegance and a brilliant facility for extracting the essence of a style of writing or of painting, Buson is multifaceted as a jewel. He can discern and emulate the many styles of Basho's work, yet his poetry is not at all like Basho's in overall tone and conception. Where we find an underlying serenity and immense depth to Basho's work, in Buson we find the range and sparkle of a virtuoso. It is as though one compared an introvert to an extrovert, a pearl with a diamond, antique velvet with silk brocade. There is a cosmic loneliness and grandeur to the man Basho. And Buson? I think Calvin L. French says it best in the art catalogue for the Asia House Gallery show:

"Buson was, of all Bunjin, * the foremost exemplar of the poetic vision. He excelled all others in the creation of mood and lyric expression. A lover of nature feels instant empathy with the artist when viewing his landscapes of trees and bamboo stalks shimmering with innumerable tones of finely textured leaf strokes so glowingly alive that one is convinced of the artist's thorough study and understanding of natural forms . . .

Whether the painting be a rich, brocade-like landscape or a scattering of rocks across a plain surface, a depiction of reveling scholars or a single figure fused with a haiku poem, all communicate an intimate, honest response to the world. In Buson's painting one finds visual expression of the joy that living should be all about." 14

And in his poetry.

Literature and

art occasionally coalesce in one individual. It is an extraordinary advantage

heightening the sensory perceptions of the one fortunate enough to be so endowed.

Yosa Buson was such a man.

-----------------------

* Literati artists in the Chinese manner were called "Bunjin" in Japan.

R. H. Blyth, Haiku Vol. II, "Spring," (Japan, Hokuseido, 1950), p. 55.

ibid, p. 47.

Blyth, Haiku, Vol. III, p. 287.

Blyth, op. cit. , Vol. II, p. 167.

Harold G. Henderson, An Introduction to Haiku (Garden City, New York, Doubleday & Company, Inc. 1958), p.97.

Asataro Miyamori, An Anthology of Haiku Ancient and Modern, p. 244 .

Blyth, op. cit., Vol. III, p. 260.

Calvin L. French, The Poet-Painters: Buson and His Followers (Univ. of Michigan, Museum of Art, 1974) p. 71.

Blyth, Haiku, Vol. I, p. 340.

ibid, p. 291.

Makoto Ueda, Basho (New York, Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1970), p. 57.

Blyth, op. cit., Vol. II, p. 301.

Henderson, op. cit., p. 96.

French, op. cit., p. 26.

Reprinted from the Red Moon Anthology 1996 and Haiku Reality ejournal.

Buson 俳諧百家仙は、 'Haika Hyakkasen'

Creativity and Aging: What the Active Lives of Older Artists Can Tell Us

--The Mature Work of Yosa Buson and the Concept of “Late Style”--

与謝蕪村円熟期の作品と晩期様式の概念

By Bruce Darling

http://artandaging.net/ronbun/busonandaging.html

Chapter 3, 2002 Grant-in-Aid Report, Ministry of Education / Japan Society for the Promotion of ScienceIntroduction

This discussion of the mature work of Yosa Buson and the concept of “late style” begins with a brief biography of Buson’s early and middle years, then turns to Buson’s last decade and his mastery of three arts_haiku poetry, painting, calligraphy. The point is made that Buson remained creatively engaged in his art right up until he died. Emphatic evidence of this is Buson’s haiga, or “haiku-spirited painting,” discussed here in relation to the concept of “late style.” Clearly an older artist can look forward to continued personal growth and still additional artistic development. The implications of Buson’s late creativity are profound.

Brief Biography of Early and Middle Aged Years

Early Years

Buson was born in Kema Village(毛馬村) in Settsu Province (present day Kema-cho, Miyakonojima-ku, Osaka) in the year 1716 (享保元年); his family name was either Tani (谷)or Taniguchi(谷口) . Very little is known about his early upbringing. His father and mother seem to have split up in 1723 when Buson was eight years old; his mother passed away in 1728, the same year Buson turned 13, the age when boys celebrated their coming of age ceremony. His father may have died about that time as well. His family probably had some status in his farming village for he had a surname; moreover a later record states he squandered his family inheritance. Buson himself said very little about his early years.

Kant_ Period

Buson apparently went to Edo in 1732 at the age of 17, though one theory claims he was twenty. His motivation remains unclear. Buson appears to have begun studying haiku with Hayano Hajin S_a (早野巴人宋阿; 1676-1742), after Hajin returned from Kyoto in 1737. Residing at Hajin’s Yahantei residence (夜半亭 ) (midnight pavilion) as a live-in student, Buson studied the haiku tradition of Bashō for Hajin had studied in Edo with two of Bashō’s early disciples, Hattori Ransetsu 服部嵐雪(1654-1707) and Enomoto Kikaku 榎本其角 (1661-1707). At some about this time he adopted the haiku go 号、or artistic name, of Saich_ 宰町(later changed to 宰鳥 .

Also during this period, Buson also pursued painting, apparently basically teaching himself. He learned by studying actual Chinese and Japanese paintings, and by examinng Chinese paintings manuals. He also seems to have been acquainted with the Confucian scholar, Chinese poet and painter Hattori Nangaku (服部南郭, 1683-1759). He took a separate go, Ch_s_ 朝滄 , for his painting. After his haikai teacher Hajin S_a died in 1742, Buson spent the next ten years or so wandering. First he stayed around Shimousa Y_ki 下総結城 (present day Ibaraki Prefecture), invited by Isaoka Gant_ 砂岡雁宕. Then he spent a year (1743) or so traveling north, retracing Bashō’s travels set down in his Oku no hosomi 奥の細道 (“Narrow road to the deep north”), through Utsunomiya, Fukushima, over the mountains to Sakata on the Sea of Japan; from there he went along the coast to Kisagata, Akiuta, Noshisro and finally reaching Sotogahama. Then he turned back south going along the eastern Pacific coast, visiting Morioka, Hiraizumi, Matsushima, Sendai and Shiroishi, before heading back to Fukushima and Y_ki. During this period he visited other students of Hajin, stayed at Buddhist temples, and made his way as a haikai teacher. The name Buson appears on a collection of “New Year Poems” 「歳旦帖」 published in Utsunomiya in 1744. Hence at the age of 29 years, we see the first use of the go 号 , or artistic name, by which he is best known, Buson, a name he may have derived either from Tao Yuan-ming’s poem “Home Again,” which includes the line “I must return. My fields and orchards are invaded by weeds ” or perhaps from his longing for his own rundown village.

During this period he also apparently wrote a beautiful elegy to an older man, Hayami Shinga 早見晋我(1671-1742)、 who had befriended him through haiku. The poem, “Mourning the Old Poet Hokuju” ([「寿老仙をいたむ」)、included in the Japanese poetry anthology 「いそのはな」), may be dated as early as 1745. He signed this with the Buddhist name “Monk Buson” 釈蕪村.

Because he was moving around so much he most likely could only study painting on his own, apparently working both with Japanese and Chinese painting styles. He left only a few paintings from this period: the fusuma paintings of “Ink Plum Trees” at the Pure Land temple Gugy_-ji 弘経寺 (Buson Zenshū (Collected works of Buson) VI, painting #10); copies of Eight landscape scenes purportedly by Wen Cheng-ming 文徴明(no signature, but passed down in the Nakamura family in Shimodate) (Buson Zenshū VI, painting #9). He often used his “Shimei” 四明 signature on his Chinese style paintings, as for example “Fisherman”(Buson Zenshū VI, painting #27)

West to Kyoto

In 1751 at the age of 37, Buson brought to an end his ten years of wandering about in the eastern and northern Japan and headed to Kyoto. He first visited fellow haiku students M_otsu (毛越) and S_oku (宋屋), the latter with whom he kept up a long close relationship. He stayed in Kyoto for about 3 years, depending on the assistance of Hajin’s disciples and living in Buddhist temples, such as a lodging affiliated with the Pure Land temple Chion-in. During these initial years in Kyoto Buson was an unknown haiku teacher; in painting as well no works have been identified from this time. His stay in Kyoto gave Buson the opportunity to examine first hand screen paintings and other traditional Chinese and Japanese scrolls preserved in Kyoto’s temples and shrines. This was a period whe Buson familiarized himself with past masters and developed his own technique.

Tango Interlude

In 1754, Buson went to the Tango (丹後) area where he stayed at the Pure Land affiliated temple of Kensh_-ji (見性寺) in Miyazu, Yosa County (与謝郡宮津). While some scholars have speculated that he went here because it was his mother’s birthplace, others believe it was because Sasaki Hyakusen (1697-1752), a Nanga painter, haiku poet, and haiga painter, had just recently sojourned here before returning to Kyoto in 1752 where he passed away. In Miyazu Chikukei 竹渓、the head priest at Kensh_-ji was one of the few people with whom to share his haiku. Another was the poet Roj_ 鷺十, to whom he gave a haiga-type ink painting of Amanohashidate (Buson Zenshū VI, haiku painting #2; calligraphy #16)with a long inscription that refers to Hyakusen:

Hassenkan Hyakusen was fond of red and blue coloring and liked paintings of

the Ming dynasty. N_d_jin Buson takes plesure in painting and also works in

the Chinese manner. Both of us admired the haiku of Bashō. Hyakusen studied

Otsuy_ (Renji) but did not imitate him. I belong to Kikaku’s group but do not

imitate Kikaku (Shinshi). Neither of us had ambition to gain a reputation through out haiku.When he came to this place on his way back to Kyoto, Hyakusen wrote this haiku:

Over Hashidate

Distant rain approaches_

The end of autumn.My haiku upon departing is:

Tail of a wagtail_

Ama-no-hashidate

Left behind me.During the three years Buson was in Tango, he seems to have focused his energy primarily on developing his painting, studying actual works of the Kano school, Sakaki Hyakusen, the yamato-e style, as well as models in Chinese painting manuals such as the late Ming early Ching poet Li Yu’s 李漁 (also known as Li Li-weng 李笠翁) Mustard Seed Garden (Chieh tzu yuan hua chuan |芥子園畫傳). Evidence from extant works includes the following: “First Emperor’s search for the Elixir of immortality,” pair of 6-fold screens, owned by Seyaku-ji (Buson Zenshū VI, painting #18); “Scene of Gion Shrine” Buson Zenshū VI, painting #20).

Settling in Kyoto

Buson, at the age of 42 years, returned to Kyoto in 1757, settling there for the rest of his life. In 1758 he changed his last name from Taniguchi to Yosa, perhaps in memory of his mother’s possible birthplace in the Tango region where he had just spent three years. He perhaps also felt a new name was appropriate for one establishing himself as a professional painter. He used several go : Ch_k_ 長康, Shunsei 春星、 Sankaken 三菓軒. He studied the colorful flower, bird and animal paintings of Shen Nanpin (c.1682-1760), e.g. “Horse Painting,” dated to 1759 (Buson Zenshū VI, painting #50; also #51), as well as other Chinese painting styles based on original scrolls as well as on examples in painting manuals. Though he was becoming quite well known as a painter, he still struggled for funds. During this time, his friends and students helped out by forming mutual financial associations (講) to help him buy supplies for painting large scale screens and smaller works as well. With such assistance, between 1763 and 1766, Buson executed perhaps as many as 24 pairs of large screen paintings on satin, silk and paper. (See Buson Zenshū VI, painting, see from #92 to #149.)

Back and Forth to Sanuki

Between 1766 and 1768, he traveled back and forth between Kyoto and Sanuki (讃岐)、 present-day Kagawa Prefecture, while in his early 50s, residing there and elsewhere in Shikoku for extended periods. While his reasons for going to Shikoku are not entirely clear, he seems to have had commissions for various paintings. On the other hand, he often stayed with people from his haiku contacts. The general tone of his painting at this time may be seen in the large fusuma-e of Japanese Cycad palm trees 蘇鉄図 he did for My_h_-ji temple (Buson Zenshū VI, painting #202). Other paintings from this time include: “Han-shan and Shih-te,” a large hanging scroll after the Ming painter Liu Ch_n 劉俊 (Buson Zenshū VI, painting #193) and “Cold forest desiring rain,” an ink landscape hanging scroll after Shen Chou 沈周 (Buson Zenshū VI, painting #194). These represent some of his Chinese style works from this time. He does not seem to have left any truly haiga paintings from his Sanuki sojourns. Comparing the works he executed in Sanuki with his later paintings, Buson, while certainly a talent artist with a vigorous brush, was still to develop as a painter.

Establishing Himself in Kyoto

Back in Kyoto Buson, in along with Tan Taigi 炭太祇 (1709-71) and Kuroyanagi Sh_ha 黒柳召波 (d. 1771), and Denpuku 田福 (1720-1793) established his first haiku group, the Sankasha(三菓社) in 1766. He apparently married and had a daughter around this time. Little is known about his wife Tomo aand his daughter Kuno though they are briefly mentioned in some of Buson’s later letters. In 1770, at the age of 55, Buson assumed the mantel of his former haiku teacher Hajin, acceding to the title Yahantei 2nd. After Taigi and Sh_ha died, Buson became the Kyoto leader of the haiku revival movement known as the “Return to Bashō” 「蕉風復興」 movement, a nationwide movement aimed at correctly understanding and conveying the essence of Bashō’s haiku. Clearly haiku poetry was playing a central role in Buson’s artistic life at this time. For example, books of poetry such as “Light from the snow” “Sono yuki kage” 『其雪影』 (1772), “Kono hotori” “Around here” 『このほとり』 and “A Crow at dawn” “Ake garasu” 『明烏』 (1773) were published around this time.

Buson also achieved recognition as a leading Kyoto painter during this period as demonstrated by the listing of his name and address as a leading Kyoto painter in the Heian jinbutsushi (平安人物志), or Kyoto Who’s Who, of 1768. He is listed here along with U`nishii , Maruyama Okyo, It_ Jakuch_, Ikeno Taiga. His address is given as 4条烏丸東へ入る町. In 1770 he moved to 室町通綾小路下る町. Buson continued to be listed as a Kyoto painter in the Heian jinbutsushi of 1775 (Buson’s was listed here along with Okyo, Jakuch_, and Taiga.). Buson was also listed in the 1782 edition. Buson’s relationships with these artists is not clear. For example, in 1771, in collaboration with Ikeno Taiga he painted the “Ten Pleasures” album leaves (signing with the go, Sha Shunsei 謝春星)to go along with Taiga’s “Ten Conveniences” album leaves in 1771 (Buson Zenshū VI, painting #23). The two artists joined in this project to illustrate twenty poems written by the poet Li Yu李漁 in praise of the ten conveniences and ten pleasures that he enjoyed at his mountain retreat Yi-yuan 伊園 on Mount Yi 伊山. The wealthy art lover who commssioned this project was Shimozato Gakkai 下郷学海 of Owari Province 尾張国鳴海 (present day Aichi Prefecture). Also, Buson and Taiga each contributed fusuma paintings in the H_j_ at Gingaku-ji,(Jish_-ji ) then under the control of the Zen temple S_koku-ji. Today, three sets of Buson’s paintings for Ginkaku-ji are extant ((Buson Zenshū VI, painting #255, 256, 257). Otherwise we know litttle about Buson and Taiga’s relationship. With Maruyama Oky_ the situation is a little clearer. The two lived near one another in the same Shij_ area of Kyoto. They had ready opportunity to meet; they both copied the same Chinese painting “Wizards of Mount H_rai” 『蓬莱仙奕』、and did a joint work (along with Goshun呉春 ) in 1774 in spite of their different painting styles. Furthermore a rather close relationship is suggested by the fact that when Buson died, his leading disciple, Matsumura Gekkei 松村月渓 (1752-1811; later known as Goshun), was welcomed into the Maruyama-Shij_ school both as Buson’s leading disciple and as a painter in his own right. Goshun later established the Shij_ school. Buson’s development as a painter during these years is demonstrated by the range of his oeuvre_landscapes, figures, flowers, birds and animals, haiga_ in various formats large and small. One of the characteristics of Buson the painter is the great diversity of styles of paintings with his signatures and seals--observable throughout this maturing period.

Buson’s Last Decade: The Mature Years

Haiku

The last decade of Buson’s life saw his creativity achieve its greatest heights. 1777 was the year of Buson’s greatest literary output. The best known works are Shunp_ batei kyoku (Melodies of the spring breeze on Kema Dike), a free verse travelogue that is a nostalgic look back at Kema combing Chinese and Japanese poems with haiku; Shin hanatsumi (New flower picking), starting out as a collection of haiku but ending up a haiku dairy with memories and stories of his early travels; Shundei kushu (Spring mud: A collection of verse), a haiku collection of Sh_ha that includes a preface by Buson with his best known statement on haiku theory:

I once met Shundeisha Sh_ha at his villa in the western suburbs of Kyoto. At that time he questioned me about haikai. I answered that the essence of haikai is to use ordinary words and yet become separate from the ordinary; be separate from the ordinary and still use the ordinary.

How to become separate from the ordinary is most difficult. A certain Zen monk said, “You should try to listen to the sound of the clapping of one hand.” This is the Zen of haikai and the way of being separated from the ordinary.

Buson continues by suggesting that Sh_ha achieve this state of mind by reading books, especially Chinese poetry, as is recommended for painters in the Li Yu’s Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting.

The principle of detachment was advocated by a certain Chinese painter. “To eliminate the mundane from a painting, there is no way other than the following, “ he said. “When you devote yourself to reading, the spirit of the books will permeate you and the earthly mood in your mind will dissipate. Anyone learning the art of painting should remember that fact.” According to his teaching, even painters are to set aside their brushes and read books. Surely the distance between haikai and Chinese poetry must be said to be shorter.

Buson’s stressing the importance of Chinese poetry to the art of haiku indicates his broad views of not only haiku but of painting as well. He even painted portraits of such favorite Chinese poets as Han Shan, Tao Yuan-ming, Li Po. He was very much in sympathy with his own teacher Hajin’s admonition to Buson when he was a young man about strict adherence to established models rather than letting one’s own creativity have free reign. Buson wrote about Hajin and his teachings about haiku in the preface to Mukashi o Ima, dated to 1744:

_.One night while he was sitting formally, he told me, “ In the way of haikai you should not always adhere to the master’s method. In every case you should be different, and in an instant, you should continue on without regard to whether you are being traditional or innovative. With this striking statement I

understood and came to know the freedom within haikai. Thus, what I demonstrate to my disciples is not to imitate Soa’s casual way but to long for sabi (elegant simplicity) and shiori (sensitivity}) of Basho, with the intention of getting back to the original viewpoint. This means to go against the external and to respond to the internal. It is the Zen of haikai and the heart-to-heart way.

As mentioned above, Buson took a leading role in the “Return to Bashō” movement in Kyoto, as is shown by his close involvement in 1776 in rebuilding of Bashō-an at Konpuku-ji, located in Ichij_-ji 一乗寺village at the foot of Mount Hiei. He wrote, among other things, a “Record of the rebuilding of Bashō’s Grass Hut in Eastern Kyoto”, depositing it in the temple. This served as a meeting place for Buson’s poetry group to gather and recite haiku and linked verse renga. In 1777 he established the Danrinkai (檀林会 ) haiku school. Buson’s haiku activities, however, apparently earned him little money. He supported himself and his family as a professional painter. His financially problems stemmed from his freely spending on food, drink and women. He enjoyed partying with friends and having a good time. He also got involved with a courtesan named Koito 小糸. A representative work is the large fusuma painting depicting “Landcape in an Evening Shower”(Buson Zenshū VI, painting #420) executed, “after the method of Ma Yuan,” when he was 65 years of age. This painting, along with other works such as the “White Plum, Red Plum” single four-fold screen (Buson Zenshū VI, painting #421), is still extant in the Sumiya 角屋 , supporting the idea that Buson was not at all a recluse who thought himself above the “dusty world.” In Buson’s day, Sumiya, a high class brothel in Shimabara district, served also as a salon for artists and poets to visit and enjoy drinking, music, and the arts. The owner at that time, Toku Uemon (haikai go-Tokuya) 徳右衛門(俳号_徳野, was a good friend who studied haiku with Buson.

Painting

Turning to the Buson’s painting in his last decade, we find at least three signatures. The signature “Buson” 蕪村 is seen on works from 1772-1782 and that of “Yahan-_” 夜半翁 is found on works dating from 1782-1783/4. The most commonly found of Buson’s names from this time is the go, or artistic name, “Sha-in” 謝寅 , found on some 172 works (of a total of 196) from the period 1778-1783/4, thus giving these productive years the name “Sha-in period.” These paintings are generally considered to include some the best representatives of Buson’s so-called Nanga paintings, works reflecting the spirit of the Chinese literati and their “Southern School” influences. Paintings with the Sha-in signature and/or seal include small hanging scrolls as well as large scale screens; subjects include, figures, birds, and landscapes, often with clear Chinese references in theme if not style. The tremendous output includes a great variety or works. Throughout Buson’s career, he read the works of Chinese poets, studied the works of various Chinese painters and depicted subjects favored by the Chinese intelligentsia. Sung, Yuan, Ming and Ching painters names we find in his inscriptions include Wen Cheng-ming, Shen Nan-p’in Ma Y_an, Mi Fu, Chao Meng-fu, Wang Meng, Liu Ch_n, Shen Chou, Tang Yin, Tung Ch’i-ch’ang.

For example, Buson’s figure painting includes a pair of scrolls depicting Tao Yuan-ming’s “Peach Blossom Spring Paradise”and dating to 1781 (Buson Zenshū VI, painting #435). Tao Yuan-ming was one of Buson’s favorite poets. The figures in this paintings seems to derive from the Ming Dynasty Che School, but ameliorated with Buson’s poetic inclinations and more relaxed brushwork. Here Buson depicts the elderly figures as happy and vigorous people clearly fully engaged in life.

Two small representative landscapes from this period such as “Clearing after a Spring Rain” (Buson Zenshū VI, painting #435) and “Cuckoo in Flight”(Buson Zenshū VI, painting #395) seem to capture their scenes at a instance of shimmering foliage, with a particular light and atmosphere. Buson’s poetic renderings call up the intent and feeling of landscapes from the Southern Sung period. Larger scale works such as a pair of screens entitled “Thatched Hut in a Bamboo Grove” and “Path through the Willow Grove” ((Buson Zenshū VI, painting #489) are executed with similar intent.

“Crows and a Kite,” a pair of hanging scrolls (Buson Zenshū VI, painting #573) with the Sha-in signature from this period have a feeling somewhat detached from Buson’s Nanga-style landscapes. The bold compositions, rapid and loose brushwork, interesting application of ink reflect again Buson’s poetic temperament. This must have been a popular Buson theme for eight other works with this theme have been catalogued (Buson Zenshū VI, painting #566-575).

A painting that has a poetic sense even closer to Buson’s haiga works is “Night Over the Snow -covered City” (Buson Zenshū VI, painting #538), one of Buson’s most loved paintings. The gray, snowy sky, the repeated patterns of the roof lines, the freshly fallen snow and the night lights adding accents to Buson’s immediate yet enduring vision. In his painting as in his haikai he wanted to be separate from the ordinary. He unquestionably succeeded here. Closely related in style is the scroll painting of Mount Gabi (Buson Zenshū VI, painting #537).

The great number and variety of paintings attributed to Buson’s Sha-in period should remind us to explore further the make up of Buson’s studio. A perusal of the paintings given in Buson Zenshū VI provides suggestions on what works one might begin with. We should also note that because this period of Buson’s oeuvre was so popular many forgeries were also produced with the “Sha-in” signature.

As might be expected with the preponderance of Sha-in signatures on Buson’s Nanga paintings, it is the signature “Buson” (蕪村) and that of “Yahan-_” (夜半翁) that appear on Buson’s haiga, which mostly date from this late period (113 of the 124 total haiga cataloged in Buson Zenshū, vol. 6, haiku paintings). Buson’s haiga may well represent his greatest contribution to the arts. One representative example is the hanging scroll “Young Bamboos”with an inscription by the artist (Buson Zenshū VI, haiku painting #38). This freshing painting, in ink on paper with faint touches of color, shows two or three faintly outlined huts seen through two stands of bamboos rendered in darker ink with thin stalks and rapidly brushed leaves. Above Buson has written:

Yes, the young bamboos_

And Hashimoto courtesans,

Are they there or not? (#626)In these haiga Buson brings together his haiku poetry and prose, his painting, and his calligraphy in full completion of a new composite art form joining these three arts. After discussing further some of the artistic developments we observe over Buson’s long career, I will return to a discussion of Buson’s haiga in relation to the concept of “late” style.

Calligraphy

Buson’s third art, calligraphy, also stands him apart. His calligraphy, too, reached its full development in his mature years. Often Buson’s brush strokes reveal no change in brush pressure and so there is little indication of his using the upper, fatter part of the brush. As with Buson’s painting, the artist seems to have taught himself with little attention to the mastery of the 8 types of brush strokes traditionally practiced in writing the character “nagai”「永」 -- we see little stopping, thrusting, jumping. In other words, Buson’s freely and easily drawn lines, suggesting a relaxed wrist, and a flexible and flowing movement from the elbow, is a perfect match for the brushwork he used for his haiga paintings. See, for example, the light-hearted, drunken, dancing depiction of “Matabei,” with an inscription by the artist, the signature “Buson” and the seals “Ch_k_” 長庚and “Shunsei” 春星 (Buson Zenshū VI, haiku painting #50). The inscription reads as follows:

The blossoms of the capital have begun to fall and scatter_

It looks like the white pigment flaking off a painting by Mitsunobu

Meeting Matabei_

We see the flowers in full bloom at Omuro (#1955)Master of Three Arts

Buson, hence, showed himself to be a master of three arts_haiku poetry, painting, calligraphy. Today Buson is ranked along side BashU` and Issa as one of Japan’s three greatest haiku poets, is ranked next to Taiga as one of the two artists who made the Chinese literati painting genres, models, and ideals into a full-fledged Japanese painting art, known as Nanga or “Southern painting,” and in acknowledged for the creation of his “haiku- spirited” calligraphy (俳諧の書).

Other important Edo period “literati” artists were also masters of more than one of the arts: Taiga was known for his painting and calligraphy, Mokubei for his painting and ceramics, Gyokudo for his painting and music. But when it comes to full mastery not only of two, but of three, arts, and then more remarkably melding these into a single new artistic form, haiga, Buson stands alone. Indeed, Buson may come closest of all the Edo period so-called literati painters to the Chinese literati ideal of “superiority in the arts of poetry, calligraphy and paintings” (「詩書画三絶」).

Also of interest is the fact that Buson’s top disciple, Goshun, took after his teacher in this respect, mastering three artistic genres-- haiku, painting and music (specifically the flute).

Creative until the End

Buson, like so many other artists, did not retire. He continued to work creatively as a poet and painter right up until he died. His Tenmei era (1781-1784) paintings confirm his vitality at this time; Buson Zenshū IV lists 136 paintings (i.e. 24% of this total painting output) and 25 haiga (i.e. 20% of his total haiga output). Buson also continued to be active in the realm of haiku poetry. As mentioned above, he was involved in the rebuilding of Bashō–an at Konpuku-ji, and he diligently attended memorial services for not only Bashō (3rd mouth, 1783) but also for his former haiku companions Taigi and Sh_ha. He left a painting with an inscription about his trip to Uji to hunt for mushrooms in September. He was taken ill and passed away at on the 25day, 12month Tenmei 3year (1783) (recalculated to January 17, 1784 in the western calendar). In his final days, his family, along with his leading disciples Baitei and Goshun, watched over him. Goshun recorded the final poem Buson whispered to him:

「しら梅に明る夜ばかりとなりにけり」(#1728)

“White plum blossoms_

In the night I thought I saw

The light of dawn”Buson was buried near Bashō at Konpuku-ji, in keeping with the wishes he expressed in an earlier poem:

我も死して碑に辺せむ枯尾花 (#1099)

When I too depart,

I’ll adorn the master’s tomb

With dried pampas grass.Buson’s Haiga and the Concept of “Late Style”

Buson’s so-called “haiga” may well represent his greatest contribution to the arts. These haiga bring together Buson’s haiku poetry, his painting, and his calligraphy in full completion of a new composite form fusing these three arts. Buson himself, it should be noted, never used the term “haiga 俳画,” calling them instead “quick drawings of haikai (i.e. “haiku”) things” (はいかい{俳諧}ものの草画). The precise definition of Buson’s “haiga,” then remains open to interpretation. After all, the term “haiga”(“haikai-e” 俳諧絵) apparently was first used by Watanabe Kazan in his Haiga-fu, or Haiga Album. Buson Zenshū VI, includes three types of paintings under the heading “haiku painting:” (1) quickly brushed drawings, sometimes with light color, accompanied by a haiku-spirited inscription (Buson Zenshū VI, haiku paintings, various numbers from #17-72); (2) somewhat more detailed portraits of Bashō (although paintings of other masters are also included) , rendered in ink and light color and accompanied typically by a longer inscription (Buson Zenshū , haiku paintings #86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 101, 102, 103, 104); (3) depictions, again rendered with somewhat more detail in ink and light color, illustrating Bashō’s haibun, or “haiku-spirited prose,” formatted as screens or horizontal scrolls (One six-fold screen illustrates “Nozarashi kik_,” or Records of a Weather-Exposed Skeleton (Buson Zenshū, haiku painting #77); three horizontal picture scrolls (Buson Zenshū VI, haiku paintings #78, 80, 859 and one six-fold screen illustrate “Oku no hosomichi,” or The Narrow Road to the deep north (Buson Zenshū, VI haiku painting #84).

Buson clearly took pride in his “haiga,” claiming in a letter to Kit_, dated 11th day 8th month 1776, that there was no artist as talented at “haikaimono no s_ga” as himself. Buson, of course, did not invent “haikaimono no s_ga” by himself. Forerunners such as Ry_ho 立圃 (1595-1669)、Saikaku 西鶴 (1624-93), and Bashō 芭蕉 (1644-94) can be named as having left haiga-like paintings. But it may well have been Sakaki Hyakusen, both a haiku poet and Nanga painter, to whom Buson is most indebted as a predecessor in the haiga genre. Buson, however, as a professional painter as well as a professional haiku master, but also endowed with wit, humor, extemporaneousness, along with clarity and lightness, brought to the haiga painting genre a completeness that sets his haiga apart from earlier examples. With Buson haiga as a genre comes into its own. Buson’s haiga, like his haiku, include the commonplace yet leave the ordinary behind, capture the moment yet allow the flow of time to continue.

Turning to the issue of “late style”, a perusal the paintings of Buson’s mature years, we can see that Buson’s mature work exhibits no single style in the late stage of his career. He continued to work in a variety of manners throughout his life while he continued to mature and develop as an artist. His so-called mature Nanga paintings hence continued to demonstrate this. Some of Buson’s later works, however, do seem to have certain qualities that relate them more closely to the spirit and technique found in his haiga paintings. Furthermore, as stated above, Buson’s haiga, or “haiku-spirited paintings,” date mostly from his last decade (113 of the 124 total haiga cataloged in Buson Zenshū, vol. 6, haiku paintings) and certainly reflect his maturity as poet, painter and calligrapher. So the question raised is whether Buson’s paintings in the haiku spirit share stylistic or other qualities with works that may be associated with what we term “late style,” after Rudolf Arnheim.

“Late style,” also referred to as “old age style,” is a term applied to a distinct phase of artistic development that comes at the end of the careers of many great artists. The validity of this rather recent concept is not without question, though discussions of the concept are found in the writing of art historians, psychologists and researchers on aging and life span development. Arnheim, for example, characterizes this phase of artistic development in the last stage of life as distinguished by “detached contemplation,” material characteristics are not longer relevant. It is characterized by a world view that “transcends outer appearances to search out the underlying essentials.” Compositions move from a stage of development in time to that of a state of “pervasive aliveness.” Arnheim uses that “term “homogenize” to describe the tendency to remove a single emphasis and to endow a work with an “evenness of texture.” “Resemblances outweigh the differences,” and these works often have a looseness in structure and placement of elements and, with regard to paintings and drawings, in the application of line and color. Kastenbaum states that “The late style is often characterized by an economy of means, a conciseness of expression in which the essence is communication without a superfluous brushstroke, word, or note.” Furthermore, such descriptive terms appear to be apt in every way when applied to Buson’s haiku-spirited paintings.

The term “late style” has generally been used to discuss the late works of artists in the western tradition such as Michelangelo, Goya, Rembrandt, Monet, Degas, to mention only a very few painters. We also see the term applied to the works of musicians, composers and writers. Generally speaking, connoisseurs tend top view the works so designated as among the most profound of these artists. Furthermore, discussions of creativity in old age often bring in the creative work of people in all sorts of other professions as well. In China, too, critics tend to lavish praise on the late work of Chinese painting masters.

On the other hand, certain Zen-spirited paintings such as Mu Ch’i’s atmospheric southern Hsiao and Hsiang landscapes or Liang K’ai’s minimalist portrait of Li Po” exhibit characteristics similar to those works described with the term “late style”, though they need not be late works themselves. Although some may be tempted to link Zen painting with haiga, Buson’s haiga are not Zen paintings. Although his work does not show any strong Buddhist tendency as such, Buson was certainly familiar with Zen teachings. The shared features of Zen painting and haiga perhaps may be attributed, at least partially, to the use of common materials and shared techniques. Furthermore, the similarity between the two may also stem from a shared maturity of vision that comprehends the world as a whole, that eliminates the superfluous, that sees and seeks to convey the world reduced to its essence. Buson’s haiga, hence, serve as a superb representative of a multi-talented mature artist’s “late style” and as such offers support for the very concept of “late style.”

The Implications of the Concept “Late Style”

The implications of the validity of the concept of “late style” are profound_an artist’s development and creativity does not necessarily continually decline with the onset of “middle age.” Rather, the middle aged and older artist, by continuing to engage in problems and risk the search for solutions to these problems, may well look forward to continued personal growth and still additional artistic development. And with time clearly running out, such an older artist may well be much more focused, both on the artistic problem itself and on the manner in which it may be resolved. Indeed, his last years may see the artist create the very best work of his career. With respect aging in general, this means that older people do not necessarily lose the ability or the will to create. Furthermore, by striving to the challenges of making something new, of seeing things in a new way, of challenging the commonplace, the older person continues to exercise his mind in an active manner. Older people, hence, can certainly look forward to the possibility of aging in a vital manner.

Note) Much of this research was conducted with support from the Ministry of Education /Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant #11680240); the discussion of vital aging and the attached bibliography on Art and Creative Aging are new.

Hundreds of poems by haiku master Buson discovered at the Tenri Central Library (October 2015)

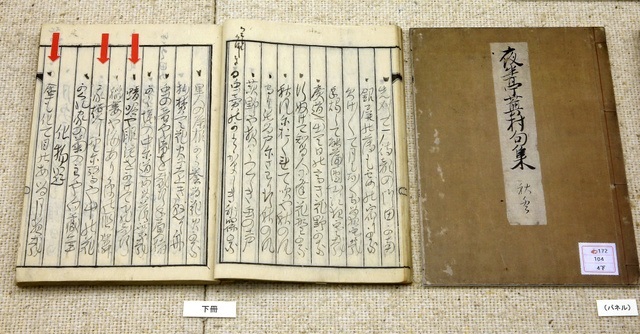

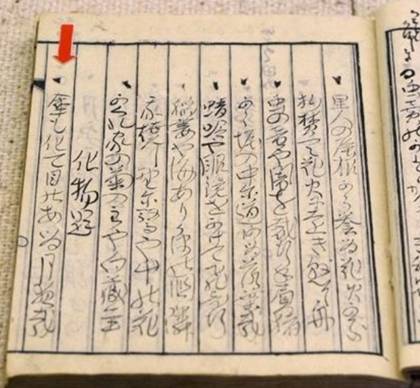

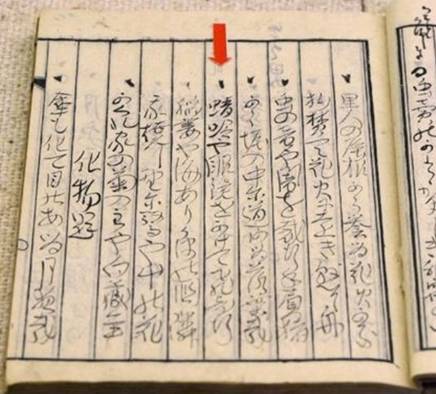

新収寺村百池旧蔵 『夜半亭蕪村句集』 春夏 Newly Acquired Yahantei-Buson-Kushū, Originally Possessed by Teramura Hyakuchi :

Spring & Summer Volumes [in Japanese]

ビブリア : 天理圖書館報 = Biblia : bulletin of Tenri Central Library (144), 88-125, 2015-10

Autumn & Winter Volumes [in Japanese]

ビブリア : 天理圖書館報 = Biblia : bulletin of Tenri Central Library (145), 81-110, 2016-05

Newly found haiku are written in the pre-published, hand written books called "Yahantei (Buson's haiku name) Buson Kushū

(haiku book)".

Red tags mark previously unknown haiku poems in the anthology.

NARA--More than 200 previously unknown poems by leading Edo Period (1603-1867) haikuist and artist Yosa Buson have been found in an anthology at the Tenri Central Library here.

Shinichi Fujita, a professor of haiku in the early modern era at Kansai University in Osaka Prefecture, said, "Buson is someone who we thought had already been thoroughly researched. It is a shock to find a compilation of his poems unknown until now."

Buson (1716-1783) is considered one of the three great haiku masters of the Edo Period, along with Matsuo Basho (1644-1694) and Kobayashi Issa (1763-1828).

The anthology contains 212 previously unknown haiku poems.

For such a large number of poems to come to light in one go is singularly rare.

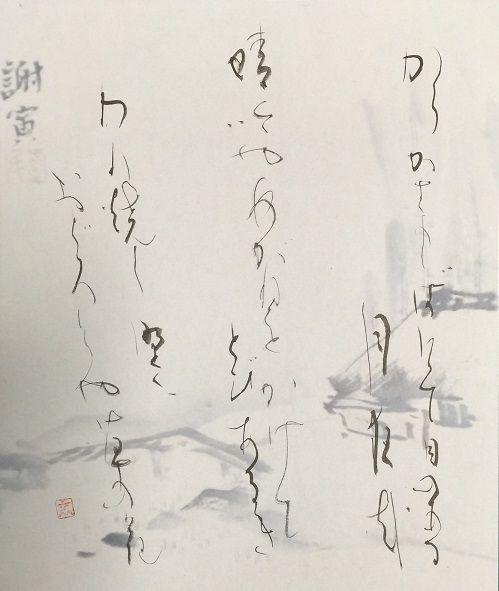

One poem goes:

傘も化けて目のある月夜哉

karakasa mo bakete me no aru tsukiyo kana

Paper umbrella

with holes poking through allows

moonlight to shine down.

Another reads:

蜻蛉や眼鏡をかけて飛歩行

kagerō ya megane o kakete tobiaruki

Large-eyed dragonfly

flies from here to there

while wearing glasses.

The poems are contained in two volumes that are copies of an anthology put together by Buson's disciples while he was alive.

Tenri Central Library (near Nara), affiliated with Tenri University, purchased the volumes four years ago from a bookstore.

Researchers cross-referenced the poems found in the anthology with the nine-volume complete works of Buson published by Kodansha Ltd. Of the 1,903 poems arranged by season in the anthology, 212 were confirmed as having been never seen before.

The anthology was known to exist even before World War II. A specialty haiku magazine published in 1934 introduced 35 poems said to be contained in that anthology. However, the whereabouts of the anthology became unclear.

These haiku are written in Sosho style calligraphy, which is very difficult to read for the modern Japanese. The Tenri University Library published the haiku in the modern letters in the library journal.

A total of about 2,900 haiku poems have been attributed to Buson.

Copyright © The Asahi Shimbun

212 haikus from Edo period poet Buson found

TENRI, Nara -- Amongst a collection of haikus held by the Tenri Central Library here are 212 previously unknown haikus by the Edo period poet Yosa Buson (1716-1783), announced the library on Oct. 14.

The new discoveries join some 2,900 haikus by Buson that were known. The library says the new collection is called the "Yahantei Buson" haiku collection, and is thought to have previously been kept in the home of the Kyoto disciple of Buson, Teramura Hyakuchi. The collection was described in a 1934 edition of the magazine "Haiku Kenkyu," after which the collection went missing until it was acquired by the library around four years ago from a bookstore.

The collection, divided by season, is organized into two books, one for spring and summer, and one for fall and winter. The collection is thought to have been put together between around 1770 and 1790. After a careful examination of the contents, the new Buson haikus were discovered among the 1,903 haikus contained in the collection. There were 57 new spring haikus by Buson, 35 for summer, 59 for fall and 61 for winter. They also had corrections and writings in black and red thought to have been added by Buson.

One haiku, with "Bakemonodai" (monster topic) written before it, reads, "The umbrella changes form, a moon-lit night with eyes," and may have been created at a haiku gathering themed on monsters. Another haiku reads, "I am surprised by a burned field, flowering grass."

Shinichi Fujita, professor of modern literature at Kansai University and a scholar of Buson, says, "Buson's haikus have been thoroughly studied, and it is amazing that a new collection of his works would appear. If the new works are compared against the many remaining letters of Buson, we may be able to learn when and against what background the haikus were made."Copyright © The Mainichi Shimbun

傘も化けて目のある月夜哉

karakasa mo bakete me no aru tsukiyo kana

my umbrella, too

becomes a one-eyed monster

this moonlit night

蜻吟や眼鏡をかけて飛歩行

kagerō ya menage o kakete tobiaruki

flying around

with his glasses on

a dragonfly

我焼し野に驚くや艸の花

ware yakishi no ni odoroku ya kusa no hana

in my burnt field

the surprise

of grass flowers

(translated by Emiko Miyashita and Michael Dylan Welch)

Selected links

http://nekojita.free.fr/NIHON/BUSON.html

http://homepage3.nifty.com/p_swkt/sw_ktji/sw_haiku/busn_lst.htm

http://www5c.biglobe.ne.jp/~n32e131/haiku/busonaki.html

http://www.elrincondelhaiku.org/int22.php?autor=34&serie=0&haiku=470

http://www.ritsumei.ac.jp/acd/cg/ir/college/bulletin/vol16-1/16-1wasserman.pdf

http://www.oligorio.com/Download/ligorio_buson.pdf

http://wkdhaikutopics.blogspot.com/2007/03/buson.html

http://www.reedscontemporaryhaiga.com/Yomeiride%20essay.htm

http://kb.osu.edu/dspace/bitstream/1811/5827/1/v11n2.pdf

http://simplyhaiku.com/SHv4n1/renku/Back_to_Basho.htm

http://www.asianartnewspaper.com/article/yosa-buson

蕪村句集本文 / Buson Hokku Book Text

http://web.archive.org/web/20050215024955/http://www.nime.ac.jp:80/~saga/sekka/kushutxt.html

Yosa Buson and His Followers: Haiku & Painting

http://web.archive.org/web/20050212052204/http://nime.ac.jp:80/~saga/buson.html

Haikai Poet Yosa Buson and the Basho Revival by Cheryl A. Crowley

http://library.globalchalet.net/Authors/Poetry%20Books%20Collection/Haikai%20Poet,%20Yosa%20Buson%20and%20the%20Basho%20Revival.pdf

Buson in Russian

http://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%81%D1%81%D0%B0_%D0%91%D1%83%D1%81%D0%BE%D0%BD

http://www.lib.ru/INPROZ/BUSON_P/buson1_1.txt (haiku)

http://www.lib.ru/INPROZ/BUSON_P/buson1_2.txt (prose)

http://www.lib.ru/INPROZ/BUSON_P/buson1_3.txt (renku)

http://web.archive.org/web/20070313140311/http://www.olguna.sitecity.ru/ltext_2308202351.phtml?p_ident=ltext_2308202351.p_2308224522