Terebess

Asia Online (TAO)

Index

Home

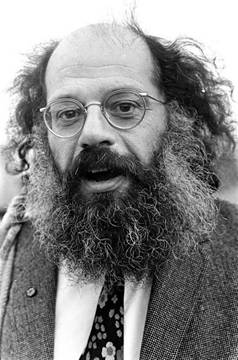

Allen Ginsberg (1926-1997)

Collected Haiku

Haiku = objective images written down

outside mind

the result is inevitable mind sensation of relations.

Never try to write of relations themselves just the images

which are all that can be written down on the subject.

- Allen Ginsberg, Journals (Fall,

1955)

Journals by Allen Ginsberg

Mostly Sitting Haiku [two versions with unpublished manuscripts:]

Corrected reprint of some verses from COLLECTED POEMS

221 Syllables at Rocky Mountain Dharma Center [13 haiku]

136 Syllables at Rocky Mountain Dharma Center [8 haiku]

American Sentences (1987-1992)

American Sentences (1995-1997)

Pastel Sentences (Selection)

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Allen Ginsberg Death Notes

by Andrew Schelling

The Prajna Paramita Sutra

as chanted by Allen Ginsberg

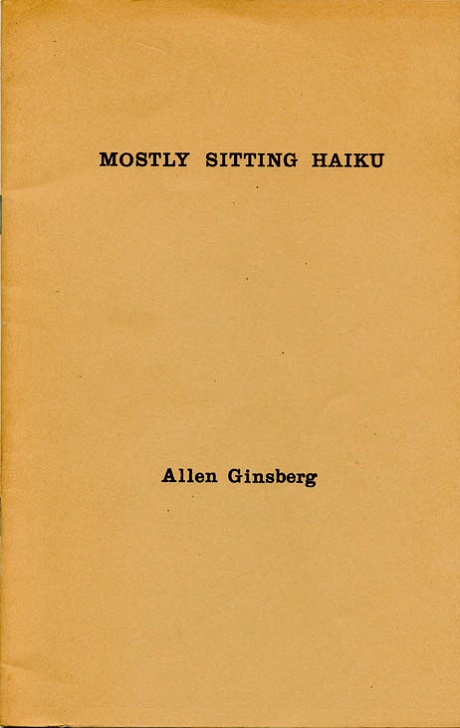

Allen

Ginsberg

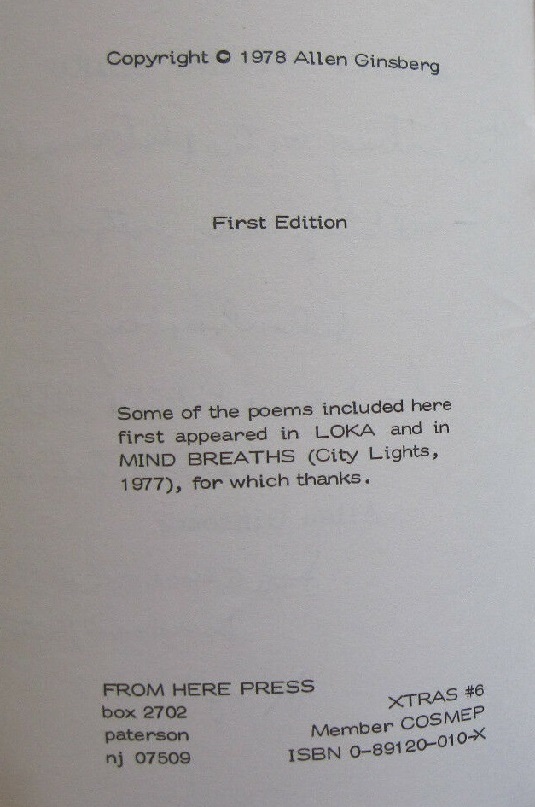

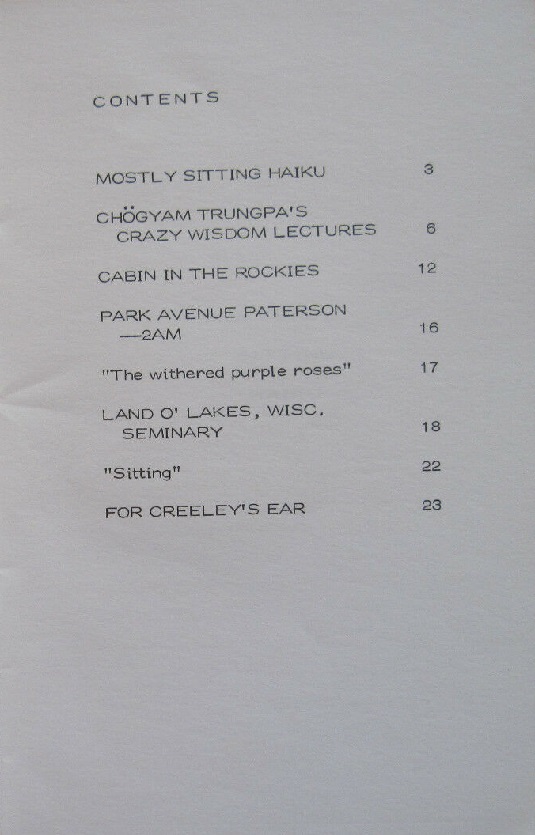

Mostly Sitting Haiku

1st ed. (Xtras, no. 6) Paterson,

New Jersey: From Here

Press, 1978. 5.5x8.5", (4)23 pp.

ISBN 0-89120-010-X

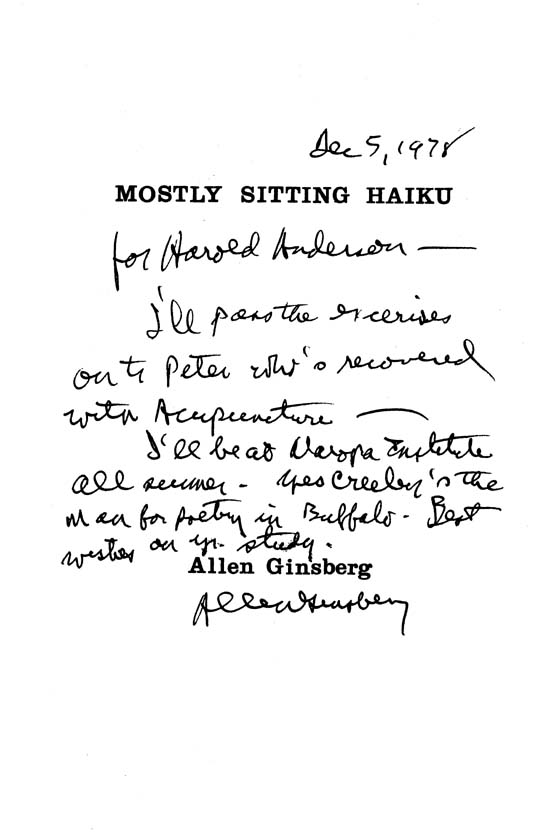

One of 500 copies with handwritten additions by Ginsberg

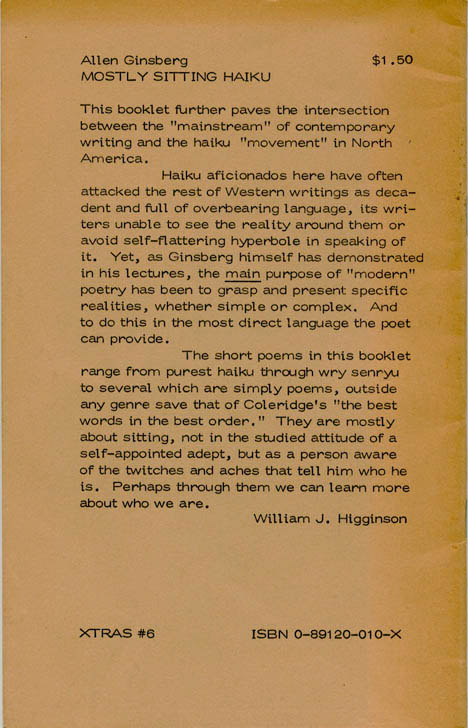

Front and back cover of the booklet. Original saddle stitched light orange wrappers, lettered in black.

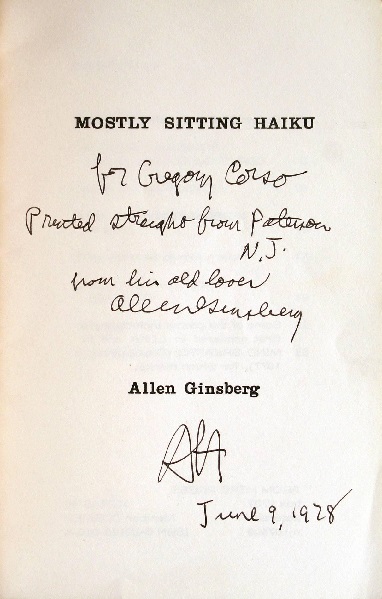

Dedication pages by A.Ginsberg:

"By product of / perceptive silence / - Allen Ginsberg / for Timothy Leary / poet / August 1, 1978."

First Edition. Inscribed presentation copy, signed by Ginsberg to fellow Beat Poet, Gregory Corso in the year of publication on the title page:

"For Gregory Corso, printed straight from Paterson, N.J., from his old lover, Allen Ginsberg, AH, June 9, 1978."

First Edition, First Printing. Signed presentation copy from Allen Ginsberg to Daniel Ellsberg.

Inscribed beneath the printed half-title:

“Still Sitting on the Plutonium tracks - meditating under empty sky - Allen Ginsberg for Dan & Patricia Ellsberg, Naropath Inst[itute],

Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, Aug 2, 1978.”

Daniel Ellsberg is famous as the man who exposed the Pentagon Papers during the Vietnam War.

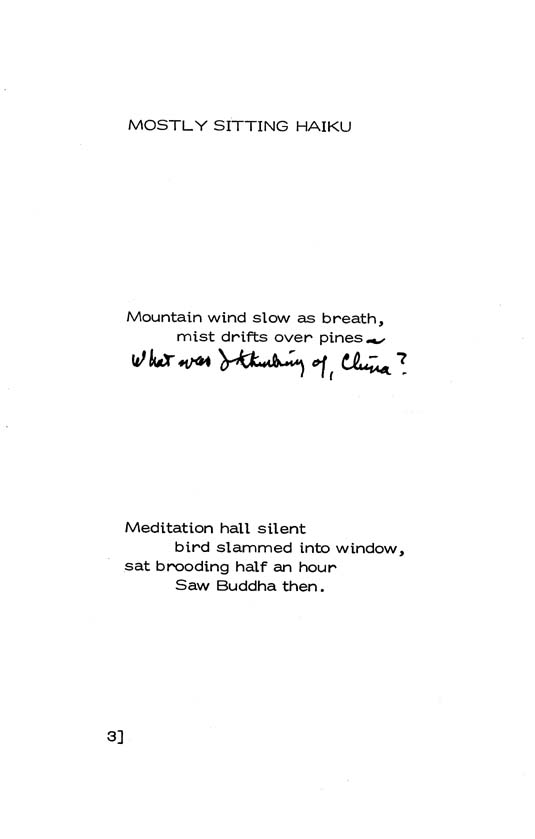

MOSTLY

SITTING HAIKU

[*another

copy with different handwritten additions by Allen Ginsberg:]

http://ginsbergblog.blogspot.hu/2013/03/allen-ginsberg-allens-haiku-2.html

Mountain

wind slow as breath,

mist drifts over pine—

I've

sat twenty days on this same pillow!

Meditation hall silent

bird slammed into window

sat brooding half an hour

Saw Buddha then.

3]

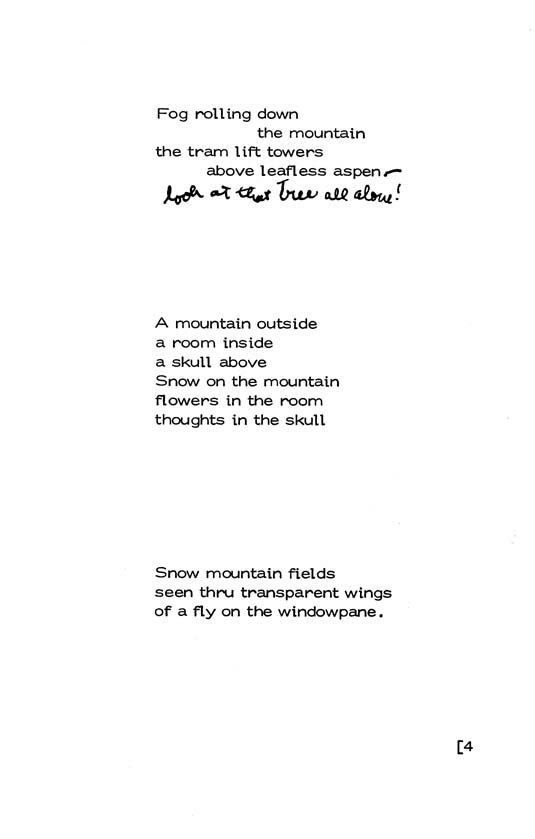

Fog rolling down

the mountain

the tram lift towers

above leafless aspen—

Clouds part and blue sky shows.

A mountain outside

a room inside

a skull above

Snow on the mountain

flowers in the room

thoughts in the skull

Snow mountain fields

seen thru transparent wings

of a fly on the windowpane.

[4

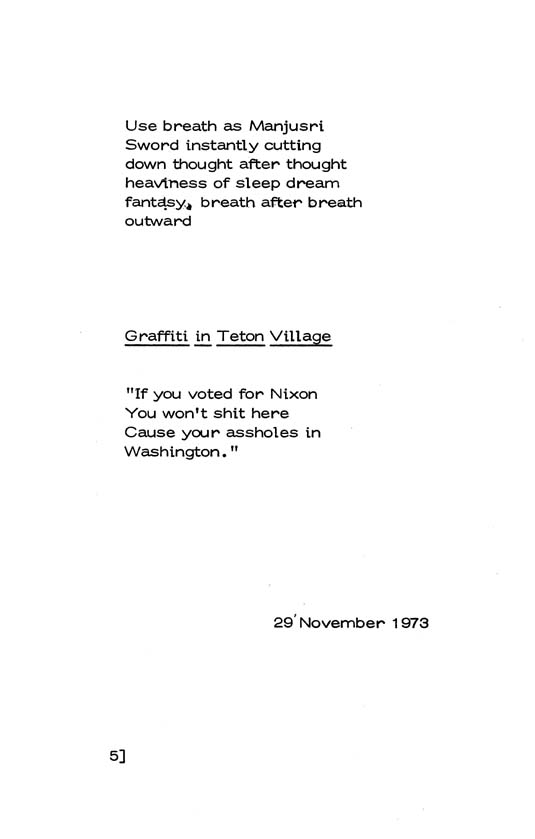

Use breath as Manjusri

Sword instantly cutting

down thought after thought

heaviness of sleep dream

fantasy, breath after breath

outward

Graffiti in Teton Village

"If you voted for Nixon

You won't shit here

Cause your asshole's in

Washington."

29’ November 1973

5]

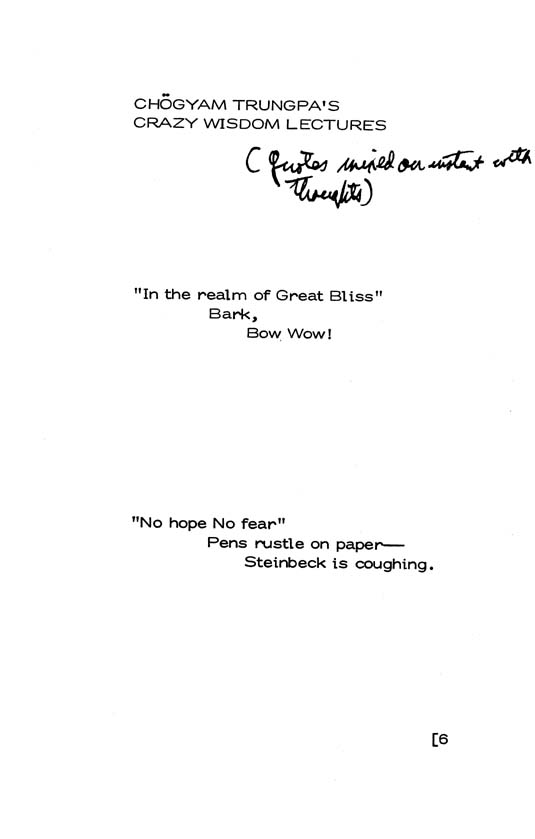

CHÖGYAM

TRUNGPA'S

CRAZY WISDOM LECTURES

– Observations Mixed With Trungpa Quotes) –

"In the realm of Great Bliss"

Bark,

Bow Wow!

"No hope No fear"

Pens rustle on paper—

Steinbeck is coughing.

[6

"Discipline, real Discipline"

Yellow carnations open

under floodlamps in the tent.

"Talk stand shit

eat sleep—"

Flies walking on my nose.

7]

"Good at the beginning

. . ."

tears roll down

my palsied right cheek.

"You're not going to get your money back"

Everybody laughing—

"Any questions?"

[8

"Willing to be Fool?"

Night moths

circle the tentpole.

Against brown grass

the hole in a black truck

tire

swings slowly between trees.

9]

"Emptiness, no need for policymaker . . ."

Secretaries lean together

at the tent wall.

"What do we mean by Craziness?"

Dogs bark to each other

across the meadow at

night.

[10

Sunlight mixed with dust

rises behind a truck

on the dirt road.

Rows of sitting heads—

blue windows, car

parked silent on grass.

August 26-28, 1975

Rocky Mountain Dharma Center

11]

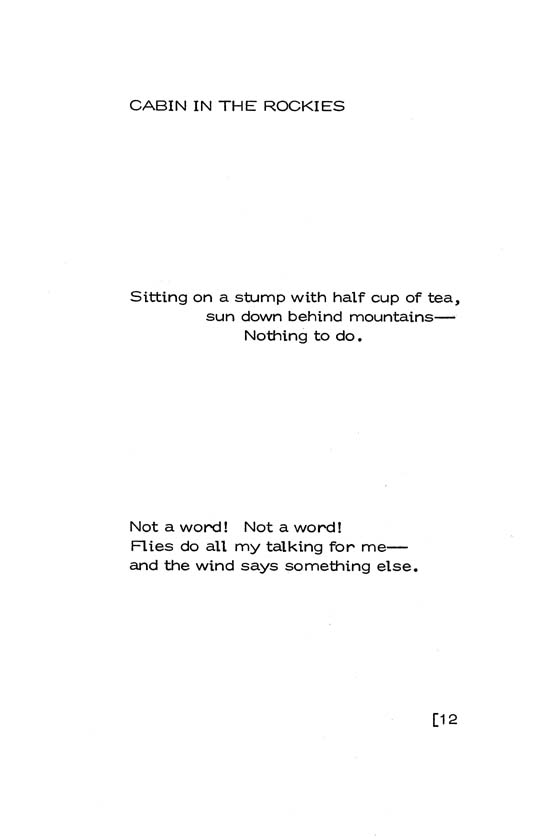

CABIN IN THE ROCKIES

Sitting on a stump with half cup of tea,

sun down behind mountains—

Nothing to do.

Not a word! Not a word!

Flies do all my talking for me—

and the wind says something else.

[12

Fly on my nose,

I'm not the Buddha,

There's no enlightenment here.

Against red bark trunk

A fly's

shadow

lights on the shadow of a pine bough.

13]

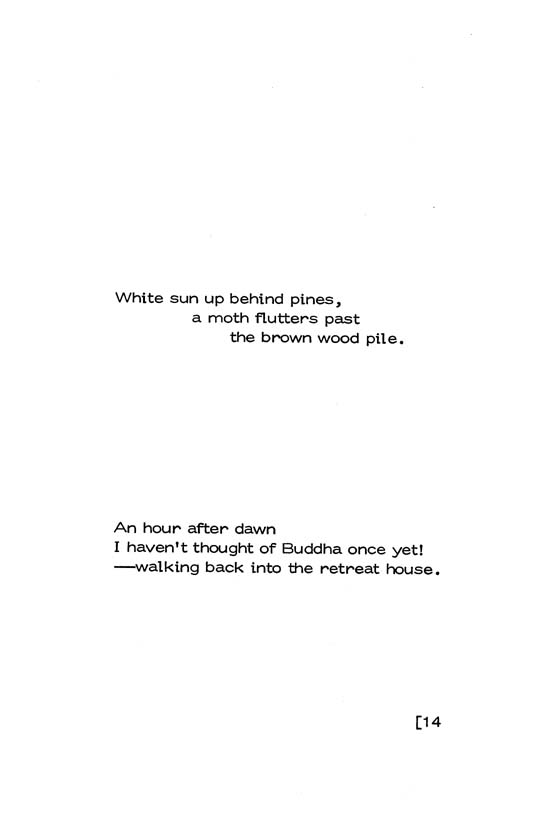

White sun up behind pines,

a moth flutters past

the brown wood pile.

An hour after dawn

I haven't thought of Buddha once yet!

—walking back into the retreat house.

[14

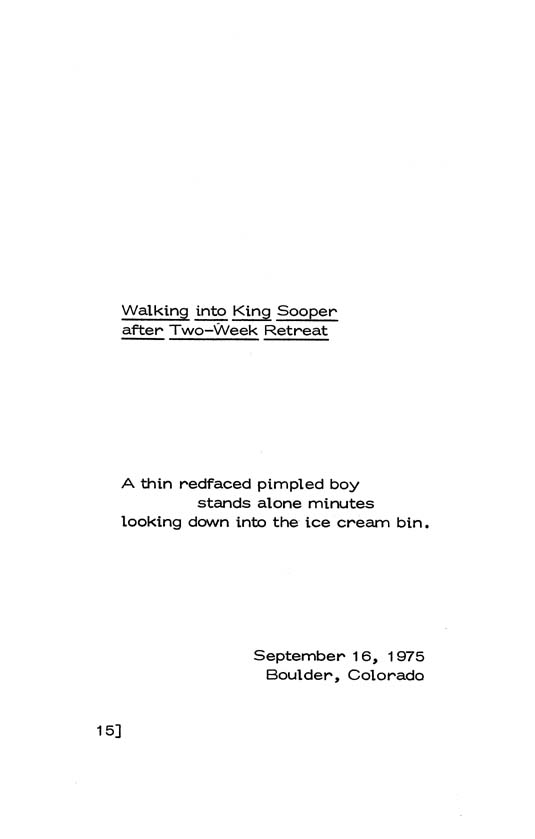

Walking

into King Sooper

after

Two-Week Retreat

A thin redfaced pimpled boy

stands alone minutes

looking down into the ice cream bin.

September 16, 1975

Boulder, Colorado

15]

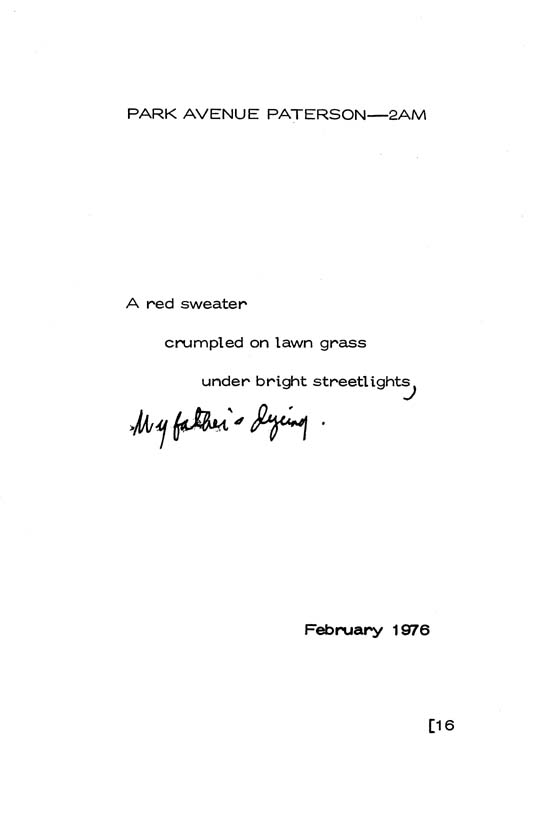

PARK AVENUE PATERSON—2AM

A red sweater

crumpled on lawn grass

under bright streetlights—

across the street from Louis' hospital.

February 1976

[16

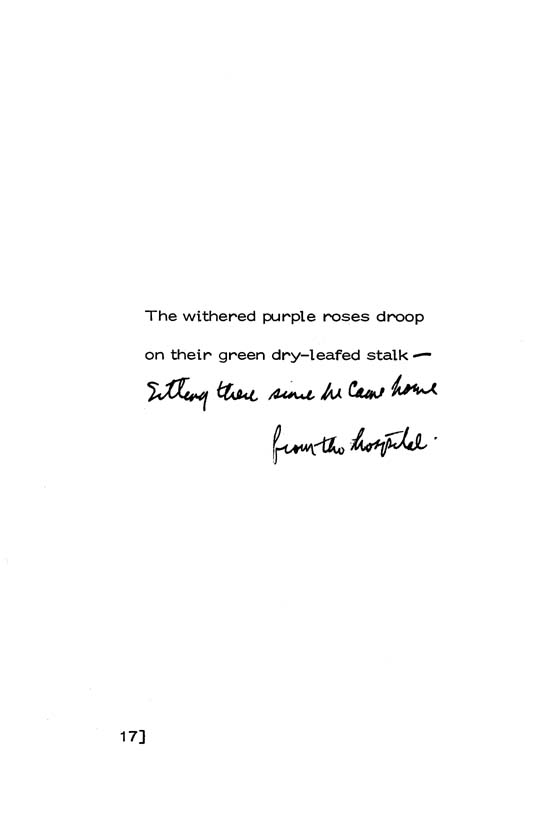

The withered purple roses droop

on their green dry-leafed stalk—

father dying cancered in the bedroom.

17]

LAND O’ LAKES, WISC.

SEMINARY

1.

I thought my mother was dead and

lamented

her

surrounded by billions of mothers

cows grass-blades & girlfriends' eyes

[18

2.

Buddha died and

left behind a

big emptiness.

19]

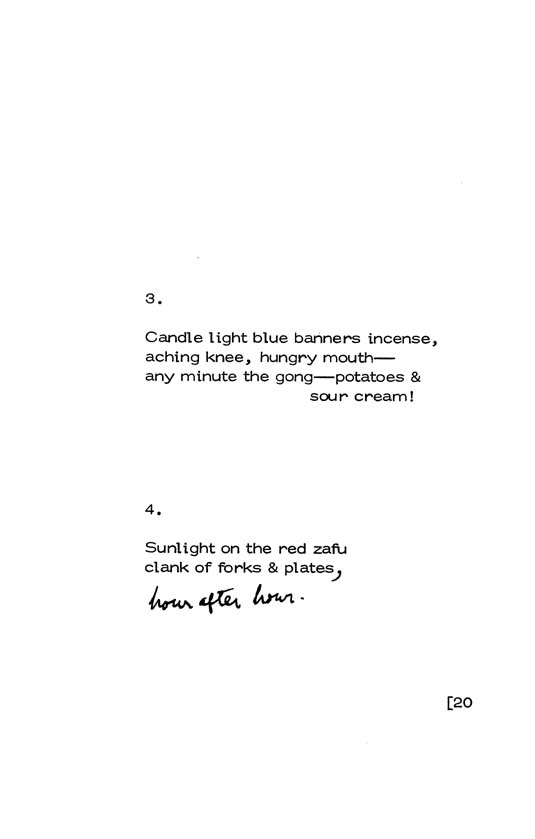

3.

Candle-light blue banners incense,

aching knee, hungry mouth—

any minute the gong—potatoes &

sour

cream!

4.

Sunlight on the red zafu

clank of forks & plates—

I used to sit like this years ago.

[20

5.

Did you ever see yourself

a breathing skull

looking out the eyes?

October 1976

21]

Sitting

under wooden roof beams

listening to a hundred people

sit

sniffing, coughing, clearing throat

sneezing, sighing

breathing through nose

shifting on pillows in clothes

swallowing saliva,

listening.

November 11, 1976

[22

FOR

CREELEY’SEAR

The whole

weight of

every thing

too much

my heart in

the subway

pounding

subtly

head ache

from smoking

dizzy

a moment

riding

uptown to see

Karmapa

Buddha tonight.

December 13, 1976

23]

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

From

COLLECTED POEMS 1947–1980:

Teton Village

Snow mountain fields

seen thru transparent wings

of a fly on the windowpane.

Cabin in the Rockies

I

Sitting on a stump with half cup of tea,

sun down behind mountains—

Nothing to do.

Not a word! Not a word!

Flies do all my talking for me—

and the wind says something else.

Fly on my nose,

I'm not the Buddha,

There's no enlightenment here.

Against red bark trunk

A fly's shadow

lights on the shadow of a pine bough.

An hour after dawn

I haven't thought of Buddha once yet!

—walking back into the retreat house.

II

Walking into King Sooper after Two-week Retreat

A thin redfaced pimpled boy

stands alone minutes

looking down into the ice cream bin.

Boulder, September 16, 1975

Land O'Lakes, Wisc.

Buddha died and

left behind a

big emptiness.

October 1976

Land O'Lakes, Wisconsin: Vajrayana Seminary

Candle-light blue banners incense,

aching knee, hungry mouth—

any minute the gong—potatoes & sour cream!

Sunlight on the red zafu

clank of forks & plates—

I'll never be enlightened.

*

Did you ever see yourself

a breathing skull

looking out the eyes?

*

under wooden roof beams

listening to a hundred people

sit

sniffing, coughing, clearing throat

sneezing, sighing

breathing through nose

shifting on pillows in clothes

swallowing saliva,

listening.

November 11, 1976

-------------------------------------------------

Allen

Ginsberg

221 Syllables at

Rocky Mountain Dharma Center

White

Shroud : Poems 1980-1985, Harper & Row,

1986 [13 Haiku on] p. 41.

Collected Poems 1947-1997,

HarperCollins Publications, 2006, [13 Haiku on] p.

883(1)

Headless husk legs wrapped round a grass spear, an old bee trembles in sunlight.

Since yesterday noon two Brown-eyed Susans stand before the outhouse door.

Tail turned to red sunset high on a spruce crown one lone chickadee tweets.

Moonless thunder — yellow dandelions flash in fields of rainy grass.

Mad at Oryoki

in the shrine-room — Thistles blossomed late afternoon.

*refers to the

shrine room (meditation hall) practice of having meals in Japanese Zen style

called oryoki

Put on my shirt and took it off in the sun walking the path to lunch.

A dandelion seed floats above the marsh grass with the mosquitos.

Empty clouds drift above me, birds chirp, a plane roar falls down through blue sky.

Electric noon — pine bough cicadas buzz outside the mashineshop door.

At 4 A.M. the two middleaged men sleeping together hold hands.

In the half-light of dawn a few birds warble under the Pleiades.

Sky reddens behind fir trees as larks twitter and sparrows cheep cheep cheep.

July 1983

Caught shoplifting ran out the department store at sunrise and woke up.

August 1983

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Allen

Ginsberg

136 Syllables at Rocky

Mountain Dharma Center

Selected

Poems 1947-1995,

HarperCollins Publications, 2001. [8 haiku on] p. 351(1)

Tail turned to red sunset on a juniper crown a lone magpie cawks.

Mad at Oryoki in the shrine-room — Thistles blossomed late afternoon.

Put on my shirt and took it off in the sun walking the path to lunch.

A dandelion seed floats above the marsh grass with the mosquitos.

At 4 A.M. the two middleaged men sleeping together holding hands.

In the half-light of dawn a few birds warble under the Pleiades.

Sky

reddens behind fir trees, larks twitter, sparrows cheep cheep cheep

cheep cheep.

July 1983

Caught shoplifting ran out the department store at sunrise and woke up.

August 1983

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Allen

Ginsberg

Haiku (Never Published)

Journals,

Mid Fifties 1954-1958

[Haiku

composed in the backyard cottage

at 1624 Milvia Street, Berkeley

1955, while reading R.H. Blyth's 4 volumes,

"Haiku."]

http://plagiarist.com/poetry/3746/

http://www.poetryconnection.net/poets/Allen_Ginsberg/3687

http://members.tripod.com/~Sprayberry/poems/haiku.txt

http://bryantmcgill.com/wiki/poetry/allen_ginsberg/haiku_never_published#.UVaLfFckSQE

Drinking

my tea

Without sugar—

No difference.

The

sparrow shits

upside down

—ah! my brain & eggs

Mayan

head in a

Pacific driftwood bole

—Someday I'll live in N.Y.

Looking

over my shoulder

my behind was covered

with cherry blossoms.

Winter Haiku

I didn't know the names

of the flowers—now

my garden is gone.

I

slapped the mosquito

and missed.

What made me do that?

Reading

haiku

I am unhappy,

longing for the Nameless.

A frog

floating

in the drugstore jar:

summer rain on grey pavements.

(after

Shiki)

On the

porch

in my shorts;

auto lights in the rain.

Another

year

has past—the world

is no different.

The

first thing I looked for

in my old garden was

The Cherry Tree.

My old

desk:

the first thing I looked for

in my house.

My

early journal:

the first thing I found

in my old desk.

My

mother's ghost:

the first thing I found

in the living room.

I quit shaving

but the eyes that glanced at me

remained in the mirror.

The

madman

emerges from the movies:

the street at lunchtime.

Cities

of boys

are in their graves,

and in this town . . .

Lying

on my side

in the void:

the breath in my nose.

On the fifteenth

floor

the dog chews a bone—

Screech of taxicabs.

A

hardon in New York,

a boy

in San Fransisco.

The

moon over the roof,

worms in the garden.

I rent this house.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

American

Sentences

(1987-1992)

Cosmopolitan Greetings:

Poems, 1986-1992 (HarperCollins, New York

City, 1994), pp. 106-108.

American

Sentences as a poetic form was Ginsberg's effort to make American

the haiku. If haiku is seventeen syllables going down in Japanese text, he would

make American Sentences seventeen syllables going across, linear, like just

about everything else in America. Unlike its literary predecessor, it included

a reference to a month and year (or alternatively, a location) rather than a

season. In Cosmopolitan

Greetings , his 1994 book, he published two and a half pages of

these nuggets, some of which had scene-setting preambles.

He used them as a tool to record life around him, simply, quickly and naked. He

discovered that the contrast of two seeming opposites was a common feature in

haiku, and used this technique in his poetry, putting together two starkly

dissimilar images: something weak with something strong, an artifact of high

culture with an artifact of low culture, something holy with something unholy.

In a 2001 interview with Anne Waldman and Andrew Schelling, Andrew said Allen's

idea for American Sentences: …was

based on haiku. He was also very interested in Buddhism for the second half of

his life, and probably the central mantra or wisdom phrase of Buddhism comes

from the Heart Sutra. It runs, “Gate Gate Paragate, Para Sam Gate Bodhi Swaha.”

And Allen discovered that has seventeen syllables also. And so he felt that maybe seventeen syllables had a more universal

application.

Tompkins Square Lower East Side N.Y.

Four skin heads stand in the streetlight rain chatting under an umbrella.

1987

* * *

Bearded robots drink from Uranium coffee cups on

Saturn's ring.

May 1990

* * *

On Hearing the Muezzin Cry Allah Akbar While Visiting

the Pythian

Oracle at Didyma Toward the End of the Second

Millennium

At sunset Apollo’s columns echo with the bawl of the One God.

* * *

Crescent moon, girls chatter at twilight on the bus ride to Ankara.

* * *

The weary Ambassador waits relatives late at the supper table.

* * *

To be sucking your thumb in Rome by the

Tiber among fallen leaves . . .

June 1990

* * *

Rainy night on Union Square, full moon. Want

more poems? Wait till I'm dead.

August 8, 1990,

3:30 AM

* * *

Approaching Seoul by Bus

in Heavy Rain

Get used to your body, forget you were born, suddenly you got to get out!

August 1990

* * *

Put on my tie in a taxi, short of breath,

rushing to meditate.

November 1991

New York

* * *

Taxi ghosts at dusk pass Monoprix in Paris 20 years ago.

* * *

The young stud who dreamt I „dick’d his ass” asked me to take him to supper.

* * *

Two blocks from his hotel in a taxi the fat Lama puched out his mugger.

* * *

I can still see Neal’s 23-year-old corpse

when I come in my hand.

Januar 1992

Amsterdam

* * *

Naropa Hot Tub

The ocean is full of naked young boys and Neptune-bearded old men.

July 1992

* * *

He stands at the church steps a long time looking

down at new white sneakers—

Determined, goes in the door quickly to make his Sunday confession.

September 21, 1992

* * *

The midget albino entered the hairy limousine to

pipi.

September 25, 1992

Modesto

* * *

That grey-haired man in business suit and black

turtleneck thinks he's still young.

December 19, 1992

* * *

American Sentences (1995-1997)

Death & Fame: Last Poems 1993-1997, (HarperFlamingo, New York City, 1999)

I felt a breeze below my waist and realized that my fly was open.

April 20, 1995

* * *

Sitting forward elbows on knees, oh what luck! to be able to crap!

April 17, 1995

“That was good! that was great! That was important!” Standing to flush the toilet.

June 22, 1995

Relief! relief! O Boy O Boy! That was necessary, wash behind!

January 18, 1997

“A good shit is worth a thousand dollars if your purse can afford it.”

February 10, 1997, 5 A.M.

Heard at every workplace—workplace— obnoxious slogan: “Shit or get off the pot!”

January 24, 1997

How did I know? How did my ass know? Suddenly, go to the bathroom!

March 10, 1997

* * *

Château d'Amboise

Sun setting on their faces the diners chatter over plates of duck.

June 22, 1995

Baul Song

“Oh my mad mind, my mad mind, where've you been all my life, my old mad mind?”

October 7, 1996

The three-day-old kitchen fly's flown into my bedroom for company.

December 9, 1996

“Hi-diddly-Dee, a poet's life for me,” Gregory Corso sang in Paris sniffing H.

January 16, 1997

Chopping apples for the fruit compote— suffer, suffer, suffer, suffer!

January 24, 1997

Courageous little lemon with so many pits! sliced into the pot.

January 25, 1997

The young dog— he jumped out the TV tube stood still then barked for supper.

January 26, 1997

Stupid of me, stupid of me, just dumb plain stupid ass! Where's my pen?

February 19, 1997, 2: 45 A.M.

My father dying of Cancer, head drooping, “Oy kindelach.”

February 24, 1997

Whatcha do about little girls who want to play Horsey on my knee?

March 10, 1997

“Hey Buster! Whatcha looking at me like that for?” in the Bronx subway.

March 10, 1997, 2: 45 A.M.

To see Void vast infinite look out the window into the blue sky.

March 23, 1997

-----------------------------------------

“Pastel Sentences” were written in Allen Ginsberg's form of American Haiku (seventeen syllables with the common haiku associational enjambment of senses but carried through on a single strophe each). These sentences were composed to accompany a set of water colors by his friend, Francesco Clemente. The New York-based Italian painter said : “ He wrote 108 short poems called Pastel Sentences in 17 syllables, haiku style. His courage and simplicity were inspiring. ”

In:

Death & Fame: Last Poems 1993-1997, ( Harperflamingo, 1999)

The author had worked out a series of 108 seventeen syllable sentences describing individual pastel paintings by Francesco Clemente. With a copy of the catalogue, he continued to polish them as he traveled on. Included here are the sentences that the Author felt could stand alone without accompanying images.

Mice ate at the big red heart in her breast, she was distracted in love.

Bowed down by the weight of nebulae he crouches underneath the hill.

A bat that’s bigger than your ear watches you sleep while you dream him there.

A round blue eye woke red lipped ’neath this century’s gigantic lightbulb.

Lantern-jawed Bismarck dreams a rich red rose blossoms thorn-stemmed through his skull.

In an oval blue womb a full-grown girl curled up eyes closed dreams her birth.

Big little people do yab yum in their ten petal’d yellow daisy.

Long hand over left eye Mother Sudan sees big bellied kids’ thin ribs.

In midst of coition a blood-red worm spurts out his heaving rib-cage.

The one eyed moon-whale watches you weep, drifting brown seas in a pale boat.

Thirty Kingdoms’ keys chainmailed down his chest, the Pope dreams he’s St. Peter.

Jeannie Duval’s cheek tickled by a Paris fly, 1852.

Puff a cigarette between skullfleshed lips, smoke gets in your empty eyes.

Sphincter-wound in his chest, he kneels and lifts both hands in surprise to pray.

All mixed up breasts feet genitals nipples & hands, both fall into sleep.

Adam contemplates his navel covered with a bush of jealous hearts.

Body spread open, black legs held down, she eats his ice cream— white sex-tongue.

One centaur palm raised thru earth-crust lifts a red live dog barking at stars.

Her dog licks the live red heart of th’ African lady curled up in bed.

Naked in solitary prison cell he looks down at a hard-on.

Hands hold her ass tight with joy to lick & eat the blue star ’twixt her thighs.

Small pink-winged Lady-Heart hovers, rose-cunt legs spread nigh his stiff black dick.

Chic shoes rest in a black rose vortex of sociable fashion money.

She poses self-confident, blue sky & clouds borne in her oval womb.

Lady Buddha sleeps on blue air in a green leaf, knees raised spread naked.

Repose open-eyed on starry blue pillows under a star-roofed sky.

The black guy steps in the shade, glancing back at the sunlit boy he screwed.

Legs behind neck, arms hung down, Yogi’s solar anal navel burns red.

Blowing bubbles in blue sky he squats on his own blue bubble planet.

Star, bird, cane & big thigh bones, the ghost baby dreams life beyond the womb.

Regarding their long thick tails, blue demons wrestle with golden scissors.

He steps on his own breast lying in bed with red half hard-on.

Lady snails delicately climb naked thighs to stir his genitals.

Left forefinger probed into his own left hand proves a Doubting Thomas.

They exchange glances, a bee shadows her tail, a rose grows on his hip.

William Burroughs’ skeleton twists a towel, he’s got the bloody rag on.

The rose-girl kneels weighed down, iron tanks on shoulder, coccyx, calves & footsoles.

Horse stands on horse upon horse, lie back on top & take your forty winks.

He dives from naked sky past the sun’s nimbus into space-blue ocean.

Curtains part on a nail and its shadow, Samsara’s drama Act I.

The red lip’d fat billionaire appeals you try out his wee twat or dick.

Arms to neck, his tit, her belly, prong-twat, the President and his wife.

Pale green headless phantoms upside-down dipsy-doodle with thin hard-ons.

Lady Day bows her neck under a pyramid of oily black rocks.

Beneath breast-eyed wasp-beaks the pink rose opens, better get in there quick!

Inside her red womb the hermaphrodite fetus closes a third eye.

Wiping blood-black tears from hard labor, try holding up your big sad head.

Jealousy! Jealousy! Chin in hand he ponders the Unfaithful Muse.

Young Don Juan bravely displays his girlish red-sexed lips and eyeshadow.

Caught in the burning house of my brown body I fainted openeyed.

Big phallus, black womb lined with reddish flesh, look at the monkey we birthed.

One bird pecks her double’s breast on a ghost-white lingam’s unblinking head.

She flies down thousands of stone steps for years, aged climbs them all back up.

for Francesco Clemente

Château Chenonceau, June 24, 1995

Naropa Institute, July 5, 1995

Lawrence, Kansas, July 22, 1995

---------------------------------

Allen

Ginsberg Death Notes

by Andrew Schelling

I first visited The Naropa Institute as guest faculty in summer of 1990. Someone

introduced me to Allen and told him I was teaching a class on Sanskrit poetics.

"What do you know about metrics of the Gayatri hymn?" he immediately asks. Gayatri is the name of an old Vedic sun

benediction comprised of twenty-four syllables which orthodox Hindus regard as

a literal goddess and some take as a great poetry Mother. This must have been

shortly after he found with delight that the mighty Buddhist mantra from the

Heart Sutra, recited all over the world, has a count of seventeen syllables.

Gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi svaha

I think he was trying to locate something comparable in the Hindu mantra which millions of Brahmans chant each dawn in India. What fascinated him in about the Heart Sutra mantra was the formal connection to haiku, Japan's 17 syllable lyric poem form rooted in Zen awareness of particulars. Allen was a veteran haiku practitioner. After all haiku exhibits the sort of irreducible clarity of perception Blake had called for, as well as a humble alternative to mythopoetic and epic bombast. Then, there is the equally irreducible effect of the Heart Sutra's closing mantra, which relies far more on shamanic traditions of sound-magic. Impressed by the synchronicity of syllable count (Allen probably knew more about metrics than any other contemporary poet, though he wore this expertise lightly) he began his series of "American Sentences," bright perceptive heartbreaking funny and thoroughly American 17 syllable poems that come at you from the page as if exercising squatter rights on derelict Asian traditions.

During July of the next six years-Naropa's summer writing program season-we'd sometimes put our heads together over the Heart Sutra. Allen worked for years refining a translation he had undertaken with his companion and Buddhist teacher Gelek Rinpoche. They of course worked the Tibetan, Gelek's native tongue. But Allen wanted to know how the Sanskrit went, since that was the Sutra's original tongue, and Sanskrit metrics, vocabulary, and sound values are interlayered, complex and magical. Furthermore, the Gate Mantra always remains in original Sanskrit no matter what language the Sutra's gone into-Chinese, Tibetan, Japanese, English-since those precise words and none other are "the great bright mantra that relieves suffering."

Mantra power resides (old Hindu yogic tradition) in exact recitation. Allen was both exhilirated and anxious about his translation project. Which makes sense. It's like toying with plutonium. This is probably why he wanted to check in with me-touch in with the Sanskrit-on particular poetic coinages. He was delighted, and a bit edgy, about his line "free of all topsy-turvy mindsets," topsy-turvy a good and etymologically exact rendering of the original word,viparyasa. Turned about or upside down. Or "imagining what is illusory or false to be real or true." Topsy-turvy gets into tender American vernacular the Buddhist sense, and is quite free of the sanctimony which sours a few translations with terms like "perverted views."

Allen's excitement around Hindu and Buddhist texts of liberation must have baffled a lot of listeners when he first began to chant mantras at poetry readings to the accompaniment of Tibetan finger cymbals or Indian shruti box (harmonium). Professors considered him silly. News magazines made fun of him. But more than anyone else he helped us see those magic early texts as poetry, and lead us away from the peculiar Occidental weirdness which wants its religion safe in church, but sends poetry adrift and lonely to street or classroom.

Poetry and enlightenment, no difference!

If he didn't come to it on his own he would have inescapably found it in India, 1962-1963. Everywhere you go in India you meet the Sufi tradition of kirtan or the Hindu bhajan-both of them big hootenanny sing-ins of religious music held on holy days or that erupt spontaneously and go through the night in village squares, neighborhood temples, or at grave of some Muslim mulla. Dour white Protestant America needed a touch of music & ecstasy, and Allen helped bring it here.

*

After visiting Naropa in summer of 1991 several Austrian writers from Vienna started a poetry school, the Schule fur Dichtung im Wien. Allen sort of served as their presiding genius. I saw him insist on several occasions to the directors that they include "a meditation component" in their curriculum or he'd lose interest. There are lots of poetry programs out there, he said, and many want him. Unless this one kept Buddhist mind discipline open as a possible influence, he wouldn't know how to distinguish it from the others.

As well as regularly inviting Allen to Vienna, Ide Hintz and Christine Huber, the Schule's directors, bring a range of other USA poets and Naropa faculty to teach in their spring and autumn two-week seasons. I went in September 1993, my first time in Europe in a dozen years. The school runs at high speed, more demanding a schedule than even the summers at Naropa, which mirror Allen's youthful high-activity style. During my stay, there was a reading staged at Vienna's big university in a cavernous basement lecture hall. Three of us read-myself, Dorothea Zeeman, a spitfire Austrian prose writer in her eighties, and Allen.

As usual Allen's presence sold out the hall. An Austrian friend says about 700 people can fit into seats. Allen read with characteristic animation, playing or beating time on the harmonium and Australian aborigine songsticks he travels with. Afterwards a group of the Schule's faculty, administrators, friends and associates went out to eat. It was quite late and we ended up at the Beograd, a Serbian restaurant down a little street and very close to the hotel the Schule had put us up in. This was the height of the war in Bosnia and there was always a nagging concern the Beograd might not be safe. Vienna lies a short automobile drive from the splintered former Yugoslavia. One of our students, a wealthy Bosnian Muslim of impeccable manners, excused himself.

The Beograd seems quintessentially Eastern, more Turkish than the "Turks" who are so despised-hung claustrophobically with intricate dark oriental carpets and no windows in the dining rooms. Brass samovars, or hammered metal wine urns on shelves. Decorative scimitars and shields, big dishes of meat grilled by waiters over a flame at your table on an actual sword. Three Ukranian kids about seventeen or eighteen had come nearly penniless to Vienna to hear Allen read. They looked like big handsome blond kids you'd find anywhere in the world, wearing leather jackets and blue jeans and boots. Quite delighted by their attentions Allen had invited them along and was buying them dinner.

Sometime into the night as we sat at a cluster of tables Allen placed his harmonium in front of him and asked the poet Bernhard Widder, seated alongside, to turn the pages of a book while he sang. Then looking the Ukranian kids in the face with immense tenderness he played his 1971 ballad "September on Jessore Road." It's a tragic and terrible poem about refugees, mostly poor rural Hindus, fleeing East Pakistan with its war and damnable starvation for Calcutta during the Bangladesh War. That Bosnian refugees were at that moment a very cruel concern to Austria added an immediate dimension to the song. Allen put everything into it. Later I questioned a few others about the moment, which I'd found unprecedented. Yes, definitely-many had never heard him so soulful.

And I realized then how little all the fame and media attention, crowds, travel, glory meant to him when he had caught the shimmering moment of no past and no future. Three handsome teen kids from the Ukraine, saying not a word, had pulled a richer, more resounding performance out of that poetry Bodhisattva than the crowd of 700 cheering him through the early evening. Everyone's world shifted a little during the ballad. When he finished and the harmonium trailed off-that mournful sound half song half locomotive whistle it makes-the group of us, maybe thirty, sat wordless. An archaic impulse, the oldest-Eros-had brought Allen to that moment-moment when love first comes over you and all the powers rise up-and I knew then that no matter what else-the politics, the goofiness, grouchiness of his later years, silly critics or fawning media-for him like for all poets Love is the original language. The body we're born to.

You think moments like that could go on forever. But humans are inestimably foolish. Only our topsy-turvy mindsets pretend such sweetness can linger. Because no sooner had Allen finished then a round gray-haired man about his own age in dusty worn-out tuxedo with a scarlet cummerbund-the house musician, a gypsy-came hustling over with a violin in his hands. Eyes impassioned and bright, he called energetically to Allen in loud German that everyone in the restaurant could hear. Now it was his turn, he let us all know. Allen had lit the place up with music. It was this man's turf, he was house musician, and now he would match the performance with what he could do.

Theatrically he released one string from his violin, then stretching it out with his left hand while he fixed the instrument tightly under his chin, he lifted dozens of weird sounds, hundreds, as he bobbed and bent and stretched and tormented that one string with his bow. Someone told me he was a longstanding practice, the evocation of bird sounds-calls, squawks, chirps, croaks, caws. He was terrific. Everyone cheered and he bowed with the largesse of a man at home.

That night I had a dream which in outline I jotted down. A week or two later I wrote it up.

Vienna Dream

I meet the

poet Allen Ginsberg at a Vienna cafe. He has hidden

himself

off at a side table, behind a potted palm. Huge Egyptian fronds bend over and

his

black harmonium sits on the table. "No difference between poetry and

meditation," he is saying distractedly as I squeeze onto a bench

alongside. "They

work the same way. Poetry and mediation." His eyes are painfully sad. I

don't

think he wanted to reach this conclusion. He looks so small and orderly in

shirtsleeves and conservative tie, almost a college professor. I should be

polite

but I'm too young, he knows it, his eyes get sadder. I'm too young for what

he's

trying to say-

"But

you meditate to end suffering," I protest, "calm your heart, keep the

guru's command." Allen sighs, he knows what's next. "While

poetry-" I'm too

strident, something's wrong, "you write poetry to get famous, travel, have

fun,

sleep with boys, be glamorous...." It's terribly

difficult, his shoulders are

slumped. I've gone too far. There's something I don't get. He stares at the

marble tabletop under the palm fringes, very gloomy, like Freud, he knows too

much, we're in Vienna, some political disaster's about to occur. "Poetry

and

meditation. No difference." He hunches over his coffee. I realize he's

trying to

warn me about something....

The old coyote! A cranky Bodhisattva up to familiar tricks. Pushing the inseparability of poetry and wisdom. His gloom to counter my tendency to be over serious. Not so different from early days when he wanted me to show him metric of the Gayatri hymn so he could maybe elicit another poem from time-honored Sanskrit pattern of three lines eight-syllables each. Now he'd come and slipped past gates of the dream to make an old point.

In Buddhism the teachers often show up in what's called the sambhogakaya, the enjoyment body. You could actually call it a body of eros without stretching things much since sambhoga literally means sexual coupling. An apparition body, described in the texts as mutable, shapeshifting, dreamlike. Check out the biography of Milarepa, or the abundant tantric tales of teachers and students zipping around in dreams and trance. Or consider the Sutra of Vimalakirti, who lives in a "ten-foot room" but seats tens of millions of sentient creatures inside, without any jostling, to hear a few choice words of poetry wisdom. These people are Allen's proper companions now I suppose.

How we'll miss him. Summers at Naropa, no longer big classes singing Blake or Shelley in white tent on dry lawn. No burgundy Mont Blanc pen looping careful thoughts at seminar table for student instruction. No Allen off evenings at summer residence Varsity Townhouse boiling up macrobiotic meals-soups or cauldrons of grain & organic root vegetables. Always obligatory to eat a bowl when you stop by for talk. He wanted to feed everyone. And each dish from every pot was indescribably bland in the same exact way. "One taste," the local Buddhists declare. What they mean is-good / bad, hot /cold, pleasure / pain-the practitioner should indifferently accept. But Allen, your generous cooking brought new life to old adage! One taste. I blow this thought after you into the shimmering void.

Gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi svaha

Andrew Schelling

9 April 1997

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Prajna Paramita Sutra

Translated by Shunryu Suzuki

http://www.cuke.com/misc/heart%20sutra%20card.html

The following chant of the Prajna Paramita Sutra, translated by Shunryu Suzuki,

was chanted by Allen Ginsberg in the CD-ROM Haight-Ashbury in the Sixties:

http://www.rockument.com/Haight/Prajna.html

MA KA HAN NYA HA RA MIT TA SHIN GYO

Great Prajna Paramita Sutra

KAN JI ZAI BO SATSU GYO JIN HAN NYA HA RA MIT TA JI SHO KEN GO

Avalokitesvara bodhisattva practice deep prajna paramita when perceive five

UN KAI KU DO ISSAI KU YAKU

skandas all empty. relieve every suffering.

SHA RI SHI SHIKI FU I KU KU FU I SHIKI SHIKI

Sariputra, form not different (from) emptiness. Emptiness not different (from) form. Form

SOKU ZE KU KU SOKU ZE SHIKE JU SO GYO SHIKI YAKU

is the emptiness. Emptiness is the form. Sensation, thought, active substance, consciousness, also

BU NYO ZE

like this.

SHA RI SHI ZE SHO HO KU SO FU SHO FU METSU FU KU FU JO

Sariputra, this everything original character; not born, not annihilated not tainted, not pure,

FU ZO FU GEN ZE KO KU CHU MU SHIKI MU JU SO GYO

(does) not increase, (does) not decrease. Therefore in emptiness no form, no sensation, thought, active substance,

SHIKI MU GEN NI BI ZETS SHIN NI MU SHIKI SHO KO MI SOKU HO MU GEN

consciousness. No eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, mind; no color, sound, smell, taste, touch, object; no eye,

KAI NAI SHI MU I SHIKI KAI MU MU MYO YAKU MU MU MYO

world of eyes until we come to also no world of consciousness; no ignorance, also no ignorance

JIN NAI SHI MU RO SHI YAKU MU RO SHI JIN MU KU SHU

annihilation, until we come to no old age, death, also no old age, death, also no old age, death, annhilation of no suffering, cause of suffering,

METSU DO MU CHI YAKU MU TOKU I MU SHO TOK KO BO DAI SAT TA E

nirvana, path; no wisdom, also no attainment because of no attainment. Bodhisattva depends on

HAN NYA HA RA MIT TA KO SHIN MU KE GE MU KE GE KO MU U KU FU ON RI

prajna paramita because mind no obstacle. Because of no obstacle no exist fear; go beyond

I SSAI TEN DO MU SO KU GYO NE HAN SAN ZE SHO BUTSU E HAN

all (topsy-turvey views) attain Nirvana. Past, present and future every Buddha depend on prajna

NYA HA RA MIT TA KO TOKU A NOKU TA RA SAN MYAKU SAN BO DAI

paramita therefore attain supreme, perfect, enlightenment.

KO CHI HAN NYA HA RA MIT TA ZE DAI JIN SHU ZE DAI MYO SHU

Therefore I know Prajna paramita (is) the great holy mantram, the great untainted mantram,

ZE MU JO SHU ZE MU TO DO SHU NO JO IS SAI KU SHIN JITSU FU KO

the supreme mantram, the incomparable mantram. Is capable of assuaging all suffering. True not false.

KO SETSU HAN NYA HA PA MIT TA SHU SOKU SETSU SHU WATSU

Therefore he proclaimed Prajna paramita mantram and proclaimed mantram says

GYA TE GYA TE HA RA GYA TE HA RA SO GYA TE BO DHI SO WA KA

gone, gone, to the other shore gone, reach (go) enlightenment accomplish.

HAN NYA SHIN GYO

NEGA WA KU WA KO NO KU DO KU O MOTTE A MA NE KU ISSAI NI OYO

What we pray, this merit with universally all existence Pervade,

BO SHI WARE RA TO SHU JO TO MI NA TO MO NI BUTSUDO O JYO ZEN KO TO

we and sentient being all with Buddhism achieve this (What I pray is that this merit pervade universally and we Buddhists and all sentient beings achieve Buddhism.)

JI HO SAN SHI I SHI HU SHI SON BU SA MO KO SA

Ten directions past, present and future all Buddhas The world honoured one. Bodhisattva, great Bodhisattva,

MO KO HO JA HO RO MI

great Prajna-paramita.

----------------------------------------

Links

A

Chronology of the Life and Times of Allen Ginsberg

Scrap Leaves

Poetry: 1947-1997

Sabine Sommerkamp. The Function of Haiku in the Development of

Ginsberg's "Howl". Walter de Gruyter, 1994