ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen index

« Home

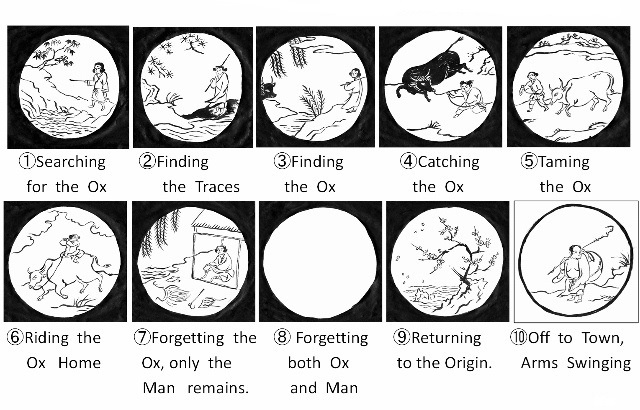

十牛圖 Shiniu tu [Jūgyūzu]

The Ten Oxherding Pictures

森哲郎 Mori Tetsurō (1928-2008)

現代と伝統:十牛図と京都哲学

Gendai to dentō: Jūgyūzu to Kyōto tetsugaku

[Modern and traditional: The Ten Oxherding Pictures and the Kyoto Philosophy]

報告の概要

http://www.kyoto-su.ac.jp/project/kikou/sekaimondai/kenkyu/20130213_kenkyu.html

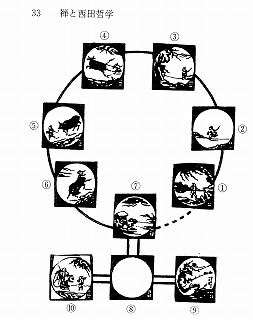

文化学部の森哲郎氏に「現代と伝統:十牛図と京都哲学」と題してお話しいただきました。3月に開催される国際シンポジウム「現代日本における世界理解:日本思想(京都学派)の可能性」の準備段階も兼ね、「神、世界、人間」という西洋理解を十牛図の視角から照らしなおす試みがなされました。第一図から第十図を一直線に見るのではなく、第一から第七図を円環にむすび、第八から第十図は一体として捉え、第七から第八への飛躍の連関が際立つように図式化する方法が提示されました。これにより、仏性に至る修行過程を一つの閉じたサイクルではなく開放性に向かう流れとして理解できるようになるとの主張がなされました。またこの<⑧・⑨・⑩>という次元の差異化は従来の「佛・法・僧」という相関図を新たな視角から再考する機会を提供すること、そして現代の「世界」を構成する関係性、すなわち「意志的(I)、社会システム的(it)、文化的 (we)」「芸術(I)、科学(it)、道徳(we)」の関係性を読み解く鍵となることが論じられました。最後に、現代社会は「it」(科学、システム)が他の領域を飲み込むほどに肥大化した時代ではないかという問いが提出されました。

The Ten Oxherding Pictures

「十牛図」 は、禅において悟りを牛に例え修行の道程を表現するために用いた説明図として知られる

*The Kyoto School (京都学派 Kyōto-gakuha) is the name given to the Japanese philosophical movement centered at Kyoto University that assimilated western philosophy and religious ideas and used them to reformulate religious and moral insights unique to the East Asian cultural tradition."[1] However, it is also used to describe several postwar scholars from various disciplines who have taught at the same university, been influenced by the foundational thinkers of Kyoto school philosophy, and who have developed distinctive theories of Japanese uniqueness. To disambiguate the term, therefore, thinkers and writers covered by this second sense appear under The Kyoto University Research Centre for the Cultural Sciences.

Cf.

森哲郎

禅の十牛図から見る西田幾多郎の「表現」思想 : ヒルデスハイム国際学会 「西田幾多郎・善の研究・百周年記念会議」

MORI Tetsurō

Kitarō Nishida's Philosophy of Expression in Light of Zen's Ten Oxherding Pictures [in Japanese].

京都産業大学日本文化研究 所 The bulletin of the Institute for Japanese Culture, Kyoto Sangyo University, 18, 491-449, 2013-03西田幾多郎 (Nishida Kitarō, May 19, 1870 – June 7, 1945), 善の研究 , 禅の十牛図 , 表現 , 純粋経験 , 思惟の道 , 「己事究明」の道 , 自覚 , 場所 , 不思議な構 造 , 第 ① 図から第 ⑦ 図までの連関と、最終の第 ⑧ ・ ⑨ ・ ⑩ 図の連関との関係 , 「空」円相 , 無の場所 , 「宗教的欲求」 (= 発心) , 平常 底 , ジョットーの一円 形

Cf.

"Nishitani Keiji and the question of nationalism" by Mori Tetsurō

In: Rude awakenings: Zen, the Kyoto school, & the question of nationalism

eds. Heisig, James W. (1944-); Maraldo, John C. (1942-)

Honolulu : University of Hawai'i Press, 1995, XV, 381 p.

Cf.

God and Nothingness

by Robert E. Carter

Philosophy East & West, Volume 59, Number 1 January 2009 1–21Zen is ever paradoxical. Hence, once one experiences the oneness of all things as pure nothingness—that is, all distinctions disappear, and there is only the one of nothingness without the many—the world reappears once more with a renewed brilliance and pinpoint sharpness, and each thing now self-manifests with an even more intense distinctness. Those familiar with the Ten Oxh erding Pictures will recognize this as the move from picture eight, of the empty circle as mu, to pic- ture nine, filled with bright blossoms, rushing water, rocks, and grass, and all with a new, intense brilliance. The enlightened individual sees both of these at once, hav- ing acquired a kind of stereoscopic vision or having become accustomed to a dou- ble exposure in seeing. Nishida uses another metaphor to describe this: the kimono hangs as beautifully as it does on the wearer because of an unseen lining deftly sewn in by a skilled seamstress or tailor. A well-tailored garment is recognizable because of the way it hangs and keeps its shape. Likewise, all things that exist are formed as they are, and yet their very form is a form of nothingness for those who can see, for a nothingness that can be discerned in each and every form. In Zen, the mountains are first lost in nothingness and then regained, but now even more brilliantly, as the form of nothingness itself, and so it is with each and every thing. In no other way is noth- ingness to be known except as each and every thing, for now one can ‘‘see'' and ‘‘feel'' the oneness of all things as absolutely nothing, and absolute nothingness as each and every thing. One sees nothingness as every thing's background or lining.

Cf.

A phenomenology of self: Ueda Shizuteru's interpretation of the Ten Ox-Herding Pictures

Steffen Döll, University of Munich, Germany

https://www.univie.ac.at/eajs/sections/abstracts/Section_8/8_5.htmUeda Shizuteru (born 1926) occupies a special position in the Japanese intellectual landscape of today: as the successor of Nishitani Keiji (1900-1990) at Kyôto University's Institute for Religious Studies he belongs to the core of the Kyôto School of Philosophy founded by Nishida Kitarô (1870-1945), while at the same time being its last representative in the strict sense of the term. Furthermore, he has made himself known in the field of religious studies with his analyses of medieval german mysticism during the last decades – especially Meister Eckhart – as well as with thoroughly instructive interpretations on the history and thought of Zen Buddhism. In spite of the great variety of his works and his regular publication of books and articles – a great amount of his writings and speeches are published in German and English – Ueda has up to this day hardly been noticed by his European colleagues. I will therefore attempt an introduction into the profundity and interconnectedness of Ueda's philosophy. His religio-philosophical anthropology, the “problem of the self”, which he addresses in a great number of his analyses, thereby serves as constant basis of interpretation. A problem providing an easy approach to Ueda's considerations is the picture text of the Ten Ox-Herding Pictures (first published in English translation in Suzuki Daisetsu's Essays in Zen Buddhism First Series 1949). This series originated from the Zen Buddhism of 12th century China, where it served as a kind of meditation manual for both monks and the laity, and is in itself equipped with commentary and poems. Even more than in China the pictures gained popularity among the Japanese laity – in the Edo period (1600-1868) they may well have been the most commonly read Zen text. Ueda takes up these ox-herding pictures and conducts by exact pictorial analyses and texual interpretations – while also referring to the complete body of the Zen tradition – a careful study of Buddhist practice. He comes to the conclusion that the advancing progress of meditation and practice, in which the practitioner distances himself from his mistaken state of being and approaches his essential existence, opens up into the “trinity of the true self,” as depicted in the last three pictures. This true self is an existence which has utterly deserted the plane of ignorant distinctions and dualities in the Buddhist sense and participates unhindered in reality, in fact is congruent with reality such as it is. That is, practice itself is rendered meaningless with the negation of conceptualized dichotomies in total: the last obstacle of one's own enlightenment is broken through into an area which can only be grasped as the nothingness depicted in picture eight. But the series does not deteriorate into nihilism; the radically consequent negation of attachment gives birth to confirmation, the “position” of reality as such (picture nine), out of the negation of negation itself. In the process of practice, negation of practice and negation of negation the self comes into the state of being in which nothingness and being and self are inseparably interconnected. Ueda's precise formula is the “self as not-self,” whose dynamic and playful action can be seen in picture ten - the encounter of self and other as the socially effective reality of the true self. Ueda finds a counterpart for his religio-theoretical speculation in Nishida's philosophy of pure experience and the theory of place (bashô). With these, he brings the experience of the Zen practitioner into an understandable and above all discursive form. At the same time theoretically conceptualized philosophy is made clear in its meaningfulness in the living, lived world. Ueda's phenomenology of self is shown to be structured as a twofold „being-in-the-world“: the self is existing and taking place in its actual, concrete environs, while at the same time and always being surrounded and permeated by the equally actual absolute nothingness. In Ueda's thought, the interconnection between the existentially performed process of Zen experience and the philosophy of place is mutually beneficent: thinking as such is concretized and unfolds its practical significance nowhere more clearly than in the last ox-herding picture, while Zen Buddhism is shown to be an also philosophically suggestive complex, which provides a vantage point from which East Asian religiosity can be considered in a new light . In conclusion, Ueda's philosophy of religion can be said to derive from the concrete, existential experience and to find a valid formulation in the critical application of philosophical terminology. Insofar as Ueda is attempting to express and transmit this experience rather than trying to explain it systematically, his is a phenomenology in the basic sense of the term.

see S. Ueda, “Das wahre Selbst—Zum west-östlichen Vergleich des Personbegriffs,” in Fernöstliche Kultur, Festschrift for Wolf Haenisch (Marburg an der Lahn, 1975), pp. 1-10.

Ueda, Shizuteru, “Emptiness and Fullness: Śūnyatā in Mahāyāna Buddhism,” James W. Heisig and Frederick Greiner (trans), The Eastern Buddhist, Spring 1982, 15.1: 9–37. (Outlines many of the contours of Ueda's understanding of Zen by way of interpreting the Ten Oxherding Pictures.)

Ueda, Shizuteru, et al. "Ten Ox-Herding Pictures - The Phenomenology of Self." Chikuma Shôbô. Tokyo, Japan. 1994.

Ueda, Shizuteru, “Nothingness in Meister Eckhart and Zen Buddhism with Particular Reference to the Borderlands of Philosophy and Theology,” in Transzendenz und Immanenz: Philosophie und Theologie in der veränderten Welt, ed. D. Papenfuss and J. Söring (Berlin, 1977), trans. James W. Heisig.

http://www.worldwisdom.com/public/viewpdf/default.aspx?article-title=%E2%80%9CNothingness%E2%80%9D%20in%20Meister%20Eckhart%20and%20Zen%20Buddhism.pdfUeda, Shizuteru, O nada absoluto no Zen em Eckhart e em Nietzsche

Nat. hum. v.10 n.1 São Paulo jun. 2008

http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?pid=S1517-24302008000100008&script=sci_arttext

Cf.

The Kyoto School: An Introduction

by Robert E. Carter

Suny Press, 2013, 258 pp.Nishitani Keiji (1900–1990): The Ten Ox-herding Pictures