ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen index

« Home

十牛圖 Shiniu tu [Jūgyūzu]

The Ten Oxherding Pictures

Introduction and verse by 廓庵師遠 Kuoan Shiyuan [Kakuan Shien], 12th century,

translated by D. T. Suzuki (鈴木大拙貞太郎 Suzuki Daisetsu Teitarō, 1870-1966)

D. T. Suzuki's first version:

"The Ten Oxherding Pictures," translated by D. T. Suzuki, in Manual of Zen Buddhism, Kyoto: Eastern Buddhist Society, 1934. London: Rider & Company, 1950, New York: Grove Press, 1960. pp. 150-171.

VIII

THE TEN OXHERDING PICTURESPreliminary

The author of these "Ten Oxherding Pictures" is said to be a Zen master of the Sung Dynasty known as Kaku-an Shi-en (Kuo-an Shih-yuan) belonging to the Rinzai school. He is also the author of the poems and introductory words attached to the pictures. He was not however the first who attempted to illustrate by means of pictures stages of Zen discipline, for in his general preface to the pictures he refers to another Zen master called Seikyo (Ching-chu), probably a contemporary of his, who made use of the ox to explain his Zen teaching. But in Seikyo's case the gradual development of the Zen life was indicated by a progressive whitening of the animal, ending in the disappearance of the whole being. There were in this only five pictures, instead of ten as by Kaku-an. Kaku-an thought this was somewhat misleading because of an empty circle being made the goal of Zen discipline. Some might take mere emptiness as all important and final. Hence his improvement resulting in the "Ten Oxherding Pictures" as we have them now.

According to a commentator of Kaku-an's Pictures, there is another series of the Oxherding Pictures by a Zen master called Jitoku Ki (Tzu-te Hui), who apparently knew of the existence of the Five Pictures by Seikyo, for Jitoku's are six in number. The last one, No. 6, goes beyond the stage of absolute emptiness where Seikyo's end: the poem reads:

"Even beyond the ultimate limits there extends a passageway,

Whereby he comes back among the six realms of existence;

Every worldly affair is a Buddhist work,

And wherever he goes he finds his home air;

Like a gem he stands out even in the mud,

Like pure gold he shines even in the furnace;

Along the endless road [of birth and death] he walks sufficient unto himself,

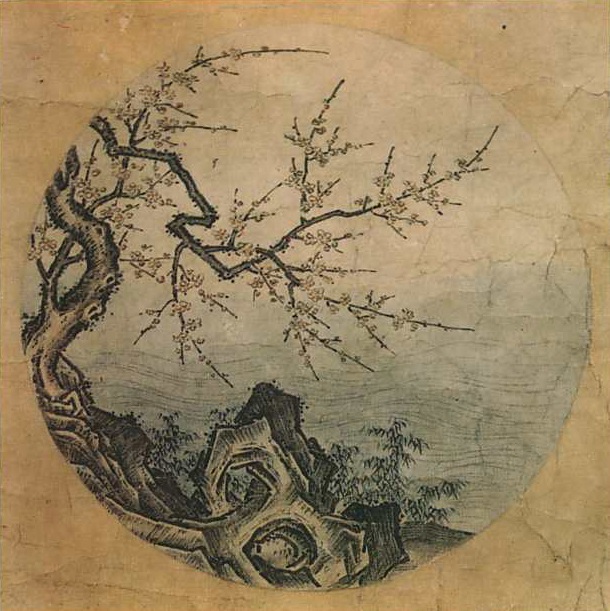

In whatever associations he is found he moves leisurely unattached."Jitoku's ox grows whiter as Seikyo's, and in this particular respect both differ from Kaku-an's conception. In the latter there is no whitening process. In Japan Kaku-an's Ten Pictures gained a wide circulation, and at present all the oxherding books reproduce them. The earliest one belongs I think to the fifteenth century. In China however a different edition seems to have been in vogue, one belonging to the Seikyo and Jitoku series of pictures. The author is not known. The edition containing the preface by Chu-hung, 1585, has ten pictures, each of which is preceded by Pu-ming's poem. As to who this Pu-ming was, Chu-hung himself professes ignorance. In these pictures the ox's colouring changes together with the oxherd's management of him. The quaint original Chinese prints are reproduced below, and also Pu-ming's verses translated into English.

Thus as far as I can identify there are four varieties of the Oxherding Pictures: (1) by Kaku-an, (2) by Seikyo, (3) by Jitoku, and (4) by an unknown author.

Kaku-an's "Pictures" here reproduced are by Shubun, a Zen priest of the fifteenth century. The original pictures are preserved at Shokokuji, Kyoto. He was one of the greatest painters in black and white in the Ashikaga period.

« D. T. Suzuki's second version

Paintings traditionally attributed to 天章周文 Tenshō Shūbun (1414-1463), ten circular paintings mounted as a handscroll, ink and light color on paper, Muromachi period, late fifteenth century (32 × 181.5 cm), Shōkokuji temple, Kyoto

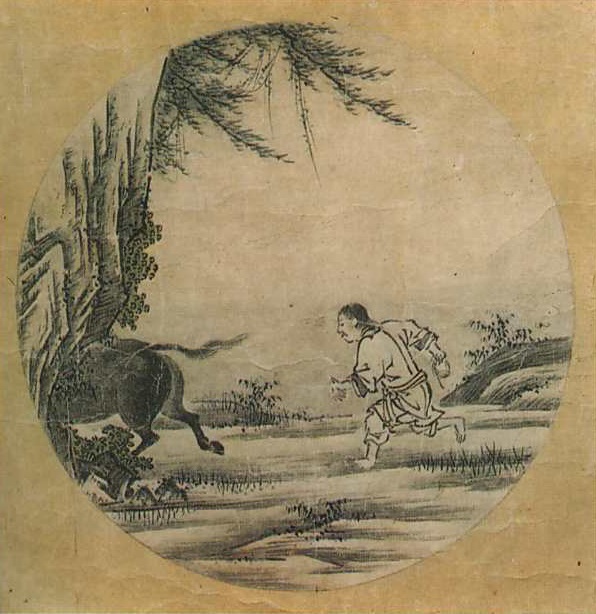

I

Searching for the Ox. The beast has never gone astray, and what is the use of searching for him? The reason why the oxherd is not on intimate terms with him is because the oxherd himself has violated his own inmost nature. The beast is lost, for the oxherd has himself been led out of the way through his deluding senses. His home is receding farther away from him, and byways and crossways are ever confused. Desire for gain and fear of loss burn like fire; ideas of right and wrong shoot up like a phalanx.

Alone in the wilderness, lost in the jungle, the boy is searching, searching!

The swelling waters, the far-away mountains, and the unending path;

Exhausted and in despair, he knows not where to go,

He only hears the evening cicadas singing in the maple-woods.

II

Seeing the Traces. By the aid of the sutras and by inquiring into the doctrines, he has come to understand something, he has found the traces. He now knows that vessels, however varied, are all of gold, and that the objective world is a reflection of the Self. Yet, he is unable to distinguish what is good from what is not, his mind is still confused as to truth and falsehood. As he has not yet entered the gate, he is provisionally said to have noticed the traces.

By the stream and under the trees, scattered are the traces of the lost;

The sweet-scented grasses are growing thick--did he find the way?

However remote over the hills and far away the beast may wander,

His nose reaches the heavens and none can conceal it.

III

Seeing the Ox. The boy finds the way by the sound he hears; he sees thereby into the origin of things, and all his senses are in harmonious order. In all his activities, it is manifestly present. It is like the salt in water and the glue in colour. [It is there though not distinguishable as an individual entity.] When the eye is properly directed, he will find that it is no other than himself,

On a yonder branch perches a nightingale cheerfully singing;

The sun is warm, and a soothing breeze blows, on the bank the willows are green;

The ox is there all by himself, nowhere is he to hide himself;

The splendid head decorated with stately horns what painter can reproduce him?

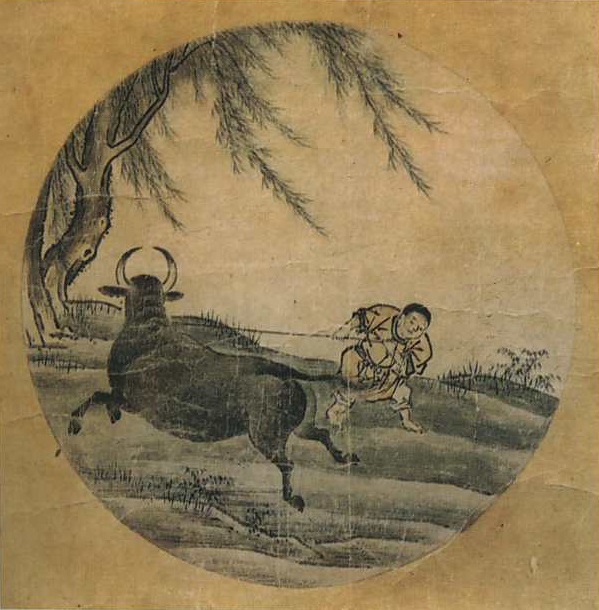

IV

Catching the Ox. Long lost in the wilderness, the boy has at last found the ox and his hands are on him. But, owing to the overwhelming pressure of the outside world, the ox is hard to keep under control. He constantly longs for the old sweet-scented field. The wild nature is still unruly, and altogether refuses to be broken. If the oxherd wishes to see the ox completely in harmony with himself, he has surely to use the whip freely.

With the energy of his whole being, the boy has at last taken hold of the ox:

But how wild his will, how ungovernable his power!

At times he struts up a plateau,

When lo! he is lost again in a misty unpenetrable mountain-pass.

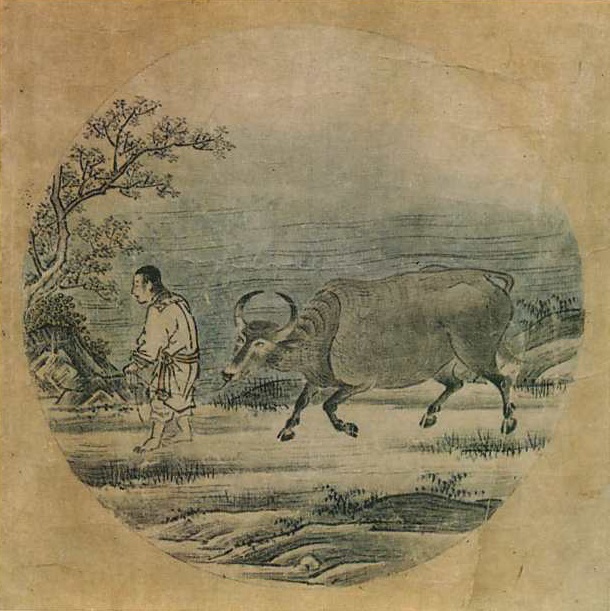

V

Herding the Ox. When a thought moves, another follows, and then another-an endless train of thoughts is thus awakened. Through enlightenment all this turns into truth; but falsehood asserts itself when confusion prevails. Things oppress us not because of an objective world, but because of a self-deceiving mind. Do not let the nose-string loose, hold it tight, and allow no vacillation.

The boy is not to separate himself with his whip and tether,

Lest the animal should wander away into a world of defilements;

When the ox is properly tended to, he will grow pure and docile;

Without a chain, nothing binding, he will by himself follow the oxherd.

VI

Coming Home on the Ox's Back. The struggle is over; the man is no more concerned with gain and loss. He hums a rustic tune of the woodman, he sings simple songs of the village-boy. Saddling himself on the ox's back, his eyes are fixed on things not of the earth, earthy. Even if he is called, he will not turn his head; however enticed he will no more be kept back.

Riding on the animal, he leisurely wends his way home:

Enveloped in the evening mist, how tunefully the flute vanishes away!

Singing a ditty, beating time, his heart is filled with a joy indescribable!

That he is now one of those who know, need it be told?

VII

The Ox Forgotten, Leaving the Man Alone. The dharmas are one and the ox is symbolic. When you know that what you need is not the snare or set-net but the hare or fish, it is like gold separated from the dross, it is like the moon rising out of the clouds. The one ray of light serene and penetrating shines even before days of creation.

Riding on the animal, he is at last back in his home,

Where lo! the ox is no more; the man alone sits serenely.

Though the red sun is high up in the sky, he is still quietly dreaming,

Under a straw-thatched roof are his whip and rope idly lying.

VIII

The Ox and the Man Both Gone out of Sight.[1] All confusion is set aside, and serenity alone prevails; even the idea of holiness does not obtain. He does not linger about where the Buddha is, and as to where there is no Buddha he speedily passes by. When there exists no form of dualism, even a thousand-eyed one fails to detect a loop-hole. A holiness before which birds offer flowers is but a farce.

[1. It will be interesting to note what a mystic philosopher has to say about this: "A man shall become truly poor and as free from his creature will as he was when he was born. And I say to you, by the eternal truth, that as long as ye desire to fulfil the will of God, and have any desire after eternity and God; so long are ye not truly poor. He alone hath true spiritual poverty who wills nothing, knows nothing, desires nothing." --(From Eckhart as quoted by Inge in Light, Life, and Love.)]

All is empty-the whip, the rope, the man, and the ox:

Who can ever survey the vastness of heaven?

Over the furnace burning ablaze, not a flake of snow can fall:

When this state of things obtains, manifest is the spirit of the ancient master.

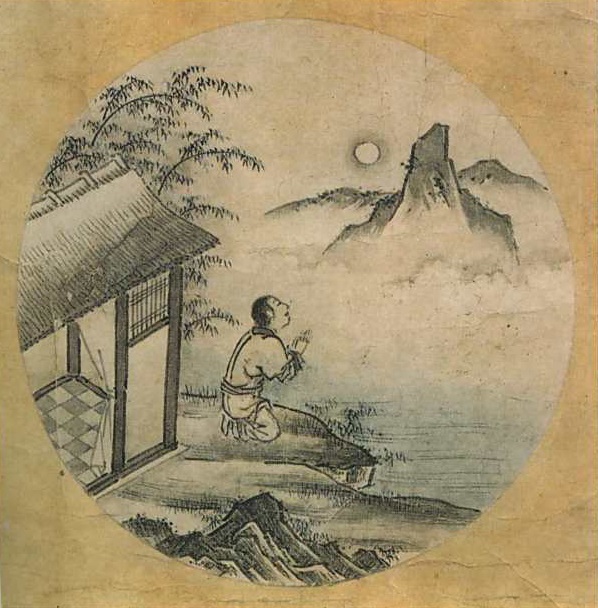

IX

Returning to the Origin, Back to the Source. From the very beginning, pure and immaculate, the man has never been affected by defilement. He watches the growth of things, while himself abiding in the immovable serenity of nonassertion. He does not identify himself with the maya-like transformations [that are going on about him], nor has he any use of himself [which is artificiality]. The waters are blue, the mountains are green; sitting alone, he observes things undergoing changes.

To return to the Origin, to be back at the Source--already a false step this!

Far better it is to stay at home, blind and deaf, and without much ado;

Sitting in the hut, he takes no cognisance of things outside,

Behold the streams flowing-whither nobody knows; and the flowers vividly red-for whom are they?

X

Entering the City with Bliss-bestowing Hands. His thatched cottage gate is closed, and even the wisest know him not. No glimpses of his inner life are to be caught; for he goes on his own way without following the steps of the ancient sages. Carrying a gourd[1] he goes out into the market, leaning against a staff[2] he comes home. He is found in company with wine-bibbers and butchers, he and they are all converted into Buddhas.

Bare-chested and bare-footed, he comes out into the market-place;

Daubed with mud and ashes, how broadly he smiles!

There is no need for the miraculous power of the gods,

For he touches, and lo! the dead trees are in full bloom.[1. Symbol of emptiness (sunyata).

2. No extra property he has, for he knows that the desire to possess is the curse of human life.]